Abstract

Setting: All 100 health facilities providing maternal services in Moyamba, Sierra Leone, a rural district that experienced a smaller Ebola outbreak than other areas.

Objective: To compare trends in antenatal care (the first and fourth visit [ANC1 and ANC4]), delivery, and postnatal care (PNC1) service utilisation before, during and after the Ebola outbreak (2014–2016).

Design: Cross-sectional study using secondary programme data.

Results: A total of 211 Ebola cases occurred in Moyamba District. The mean number of monthly ANC visits remained stable over time, except for the subset of care provided via outreach visits where, compared with before the outbreak (n = 390), ANC1 visits declined during (n = 331, P = 0.002) and after the outbreak (n = 342, P = 0.03). Most (>97%) deliveries occurred in health facilities, assisted by maternal and child health aides (>80%). During the outbreak, the mean number of community-based deliveries per month declined from 31 to 21 (P = 0.03), and the mean number of deliveries performed by midwives increased from 49 to 78 (P < 0.001) compared with before the outbreak. Before, during and after Ebola, there was no significant change in the mean number of live births (respectively n = 1134, n = 1110, n = 1162), maternal PNC1 (respectively n = 1110, n = 1105, n = 1165) or neonatal PNC1 (respectively n = 1028, n = 1050, n = 1085).

Conclusion: In a rural district less affected by Ebola transmission than other areas, utilisation of maternal primary care remained robust, despite the outbreak.

Keywords: labour and delivery, maternal health, West Africa, health systems strengthening, operations research

Abstract

Contexte : Les 100 structures de santé offrant des services de santé maternelle à Moyamba, Sierra Leone, un district rural qui a connu une petite flambée épidémique d'Ebola.

Objectif : Comparer les tendances en matière d'utilisation des services de consultation prénatale (ANC1 et ANC4, c'est-à-dire la première consultation and la quatrième consultation ANC), d'accouchement et de soins postnataux (PNC1) avant, pendant et après la flambée épidémique d'Ebola (2014–2016).

Schéma : Etude transversale recourant aux données secondaires du programme.

Résultats : Il y a eu 211 cas d'Ebola dans le district. Le nombre moyen mensuel des ANC est resté stable dans le temps, à l'exception du sous-ensemble de soins offert à travers des stratégies avancées où, comparé à la période précédant la flambée épidémique (n = 390), les ANC1 ont décliné pendant (n = 331 ; P = 0,002) et après Ebola (n = 342 ; P = 0,03). La majorité des activités (<97%) a eu lieu dans des structures de santé, assistées par des auxiliaires de santé maternelle et infantile (<80%). Pendant la flambée épidémique, le nombre moyen d'accouchements ayant eu lieu en communauté par mois a décliné de 31 à 21 (P = 0,03), et le nombre moyen d'accouchements réalisés par des sages-femmes est passé de 49 à 78 (P < 0,001) par comparaison à la période antérieure. Il n'y a pas eu de changement significatif avant, pendant et après Ebola, dans le nombre moyen de naissances vivantes (n = 1134, n = 1110, n = 1162), de ANC1 maternelles (n = 1110, n = 1105, n = 1165) ou de consultation néonatales (n = 1028, n = 1050, n = 1085).

Conclusion : Dans un district rural moins affecté par la transmission d'Ebola, l'utilisation des soins de santé primaires maternels a résisté à la flambée épidémique.

Abstract

Marco de referencia: Los 100 establecimientos de atención de salud que cuentan con servicios de maternidad en Moyamba, un distrito rural de Sierra Leona donde el brote epidémico por enfermedad del Ébola fue menos intenso.

Objetivo: Comparar las tendencias de la utilización de los servicios de atención prenatal (ANC1 et ANC4, es decir, la primera y la cuarta atención ANC), parto y atención posnatal (primera cita postnatal) antes del brote de enfermedad del Ébola, durante el mismo y después de él (del 2014 al 2016).

Método: Fue este un estudio transversal con datos secundarios de los programas.

Resultados: Se presentaron 211 casos de enfermedad por el virus del Ébola en el distrito. El promedio de consultas mensuales de atención prenatal permaneció estable con el transcurso del tiempo, con la excepción del subconjunto de cuidados prestados por conducto de citas extrainstitucionales, donde en comparación con el periodo anterior al brote (n = 390), las citas por ANC1 disminuyeron durante el brote (n = 331; P = 0,002) y después del mismo (n = 342; P = 0,03). La mayoría de los partos (>97%) tuvo lugar en los establecimientos sanitarios, atendido por auxiliares de salud maternoinfantil (>80%). Durante el brote epidémico, el promedio mensual de partos atendidos en la comunidad disminuyó de 31 a 21 (P = 0,03) y el promedio de partos atendidos por parteras aumentó de 49 a 78 (P < 0,001) en comparación con el período anterior al brote. No se observó ningún cambio significativo antes del brote, durante el mismo o después de él, con respecto al promedio de nacidos vivos (n = 1134, n = 1110 y n = 1162), ANC1 (n = 1110, n = 1105 y n = 1165) ni de primeras consultas posnatales del recién nacido (n = 1028, n = 1050 y n = 1085).

Conclusión: En un distrito rural menos afectado por la transmisión de la enfermedad del Ébola, la utilización de los servicios primarios de atención materna resistió al brote epidémico.

During the 2014–2015 outbreak of the Ebola virus disease (EVD) in Sierra Leone, at least 3589 people died of EVD, including more than 200 health care workers.1 The impact of the outbreak extended beyond EVD to affect the entire health care system.2,3 Access to antenatal care (ANC) and postnatal care (PNC) services reduces maternal and infant mortality, and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a series of four ANC visits and at least one PNC health visit.4 Four ANC visits contribute to better health choices, such as safe deliveries in health facilities with the assistance of a skilled birth attendant.5 ANC visits also reduce maternal mortality and adverse pregnancy outcomes and increase access to PNC services soon after delivery.6 Almost half of postnatal deaths occur within the first 24 h, and 66% occur within the first week,6 and early PNC care reduces postnatal complications.7 Three of the 11 indicators recommended by the WHO to evaluate reproductive and child health programmes are 1) completion of prenatal care (four ANC visits); 2) delivery at a health facility and/or attendance by a skilled provider; and 3) access to PNC within 2 days of childbirth.8

Even before the outbreak, Sierra Leone had one of the highest maternal mortality ratios globally, at 1165 deaths per 100 000 live births,9 and delivery of ANC and PNC services in Sierra Leone was suboptimal. The health system was recovering from a civil war and there were significant shortages in health care staff.10 The 2013 Demographic Health Survey indicates that while women often initiated ANC after the first trimester, they did not receive or attend all four ANC visits as recommended.4 In 2013, 75% of women completed prenatal care, 54% delivered at a health facility and 70% had a PNC visit within 2 days of childbirth.4

The Ebola outbreak may have further compromised ANC and PNC in different ways. Early on in the outbreak, health workers were instructed to strictly follow an overarching ‘no touch’ policy when sufficient personal protective equipment (PPE) and training were not available, which impacted the provision of care for pregnant and postnatal women and neonates.11 Community perceptions of an increased risk of contracting EVD in health facilities may have prevented women from accessing ANC and PNC services or from delivering at health facilities.12 No peer-reviewed studies in affected countries have specifically assessed the effects of the outbreak on the complete continuum of ANC, delivery and PNC.

The aim of the present study was to determine the effects of the 2014–2015 Ebola outbreak on attendance and completion of ANC and PNC visits and on facility delivery in Moyamba District, Sierra Leone. Specific objectives were to compare before, during and after the outbreak: 1) attendance at the first (ANC1) and fourth (ANC4) visits by site of visit (i.e., facility and outreach) and type of facility; 2) the number of women delivering at a health facility or at home, and by cadre of birth attendant; and 3) the number of mothers and neonates receiving PNC within 2 days of childbirth.

METHODS

Study design

We conducted a comparative cross-sectional study using routinely collected, aggregate programme data over three time periods.

Study setting

General

Sierra Leone, a low-income country in West Africa, ranked 181 out of 188 on the Human Development Index in 2014 following a civil war that lasted from 1991 to 2001.13

Study site setting

The district of Moyamba, in the Southern Province of Sierra Leone, has an estimated population of 300 000 across its 14 chiefdoms.14 Each chiefdom has a community health centre (CHC), a community health post (CHP) and a maternal and child health post (MCHP), where ANC, delivery services and PNC can be accessed.14 The district also has five Basic Emergency Obstetrics and Newborn Care centres (BEmONC), which provide a higher level of obstetric and neonatal care, such as assisted deliveries. The district referral hospital is located in the district capital. In addition, there is one faith-based hospital, and one university hospital that services local university students. Caesarean section and complicated obstetrical emergencies are managed only at hospitals. Table 1 summarises the function and staffing of the different types of health facility.

TABLE 1.

Overview of the public health system and staffing by facility type in Moyamba District, Sierra Leone; Moyamba District Health Management Team Report, 2016

The EVD outbreak in Moyamba District occurred between 23 July 2014 and 17 March 2015, with 211 cases across 10 chiefdoms, and 126 EVD-related deaths, including five health care staff. Four chiefdoms reported more than 20 cases each.15

Study population

The study population included all registered pregnant women in Moyamba District attending ANC visits, delivering at the health facilities or in the communities, and women and neonates attending PNC1 visits within 2 days of childbirth before (1 June 2013–30 April 2014), during (1 June 2014–30 April 2015) and after (1 November 2015–30 April 2016) the Ebola outbreak.

Data collection

We extracted peripheral health unit (PHU) data from the District Health Information System (DHIS) software, which is generated from routine monitoring and evaluation forms, registers and tally books for reproductive and child health. Data on referral hospital deliveries were extracted from a paper register used for routine monitoring and evaluation.

We extracted the following data per facility: month, year, chiefdom, health facility type (CHC, CHP, MCHP, hospital), number of ANC visits (ANC1–ANC4), site of visit (facility or outreach [facility-based outreach to the community]), number of deliveries, health cadre of the birth attendant, place of delivery (facility or community), number of live births, and number of mothers and babies attending first PNC visit.

Data analysis

A structured database was developed in EpiData version 3.1 (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark), and data were double-entered. EpiData version 2.2.2.182 was used for analysis. Trends in outcomes per month were explored and outcomes compared by study period using the t-test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for proportions. For each outcome, pre- vs. during EVD and pre- vs. post-EVD were compared. Each comparison included the same calendar months to counter potential seasonal variations in outcomes. The pre- vs. post-outbreak comparisons were restricted to the months inclusive of November to April in each time period.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Sierra Leone National Ethics and Scientific Review Committee, the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation, Freetown, Sierra Leone, and the Ethics Advisory Group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France. As aggregate data were used, with no names and no patient identifiers, informed patient consent was not required.

RESULTS

Monthly reports were available from all 100 health facilities for each study month. One CHP was reporting (and therefore classified) as a CHC up until December 2014. Of the 2728 reports, 103 (4%) were missing data on at least one indicator of interest, and 24 (0.1%) were missing data on all five programme indicators of interest (ANC1, ANC4, number of deliveries, number of live births, first PNC visit). Completeness of reports was similar before (1027/1056, 97%) and during the outbreak (1037/1072, 97%), and was lowest after the outbreak (561/600, 94%, P = 0.01).

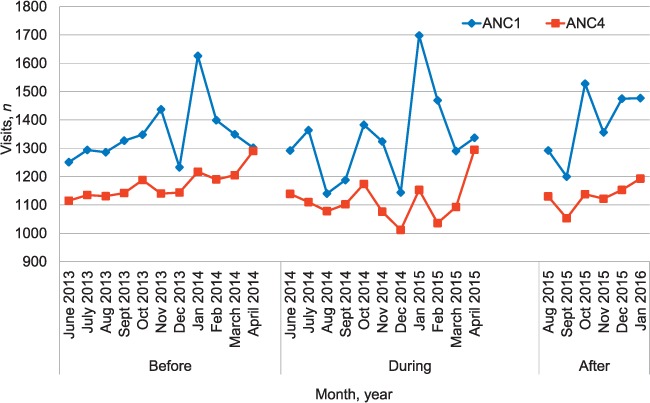

Antenatal care cascade

The monthly trends in ANC1 and ANC4 visits are shown in Figure 1. There were seasonal fluctuations in ANC1 visits across the study periods; however, compared with pre-EVD, there was no significant difference in the mean number of ANC1 visits per month during or after the outbreak (Table 2). The type of facility did not affect uptake of ANC care during the outbreak, and the number of facility-based ANC1 visits remained unchanged in all study periods. However, the number of ANC1 outreach visits was lower during (331 vs. 390, P < 0.002) and after (342 vs. 399, P = 0.03) the outbreak than before the outbreak. The mean number of ANC4 visits was also lower after the outbreak than before (1131 vs. 1198, P = 0.05), as well as in the subset of those receiving ANC4 visits at a CHP (305 vs. 340, P = 0.02). There was an increase in the mean number of ANC4 visits after the outbreak (627 vs. 465, P = 0.01) in the subgroup of those receiving outreach care.

FIGURE 1.

ANC clinic visits (ANC1 and ANC4*) by month before, during and after the EVD outbreak in Moyamba District. There is seasonal variation in monthly numbers due to closure of facilities during December and a consequent increase in January. *ANC1 = first ANC visit; ANC4 = forth ANC visit. ANC = antenatal care; EVD = Ebola virus disease.

TABLE 2.

ANC visits by facility type and health care setting before, during and after the EVD outbreak, Moyamba District, Sierra Leone

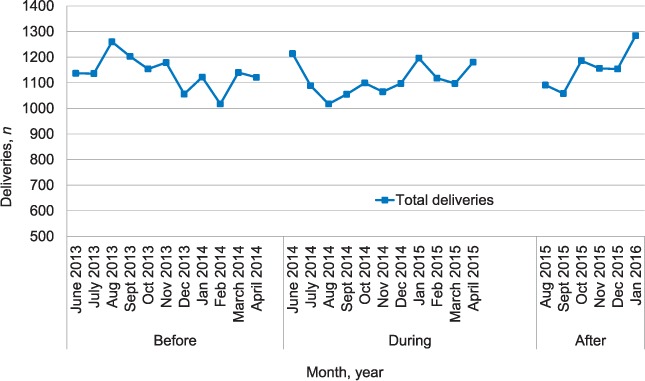

Deliveries by location and by health cadre

The total number of deliveries by month remained stable over the study periods (Figure 2). There were higher mean numbers of institutional deliveries per month by unskilled birth attendants (respectively n = 1057, n = 999, n = 1002) than by skilled birth attendants (respectively n = 86, n = 113, n = 151; all P < 0.02) before, during and after the outbreak. There was a decline in community-based deliveries during the outbreak (P = 0.03) (Table 3). During and after the outbreak, the mean number of deliveries performed by midwives increased (n = 78 and n = 102 vs. n = 49; both P < 0.001) compared with before the outbreak, with a concomitant trend towards significance of a decrease in the mean number of deliveries per month by unskilled maternal and child health aides, who performed more than 80% of deliveries before (963/1093), during (920/1111) and after (939/1153) the outbreak.

FIGURE 2.

Total number of deliveries by month before, during and after the Ebola virus disease outbreak in Moyamba District.

TABLE 3.

Number of deliveries by setting and cadre before, during and after the EVD outbreak in Moyamba District, Sierra Leone

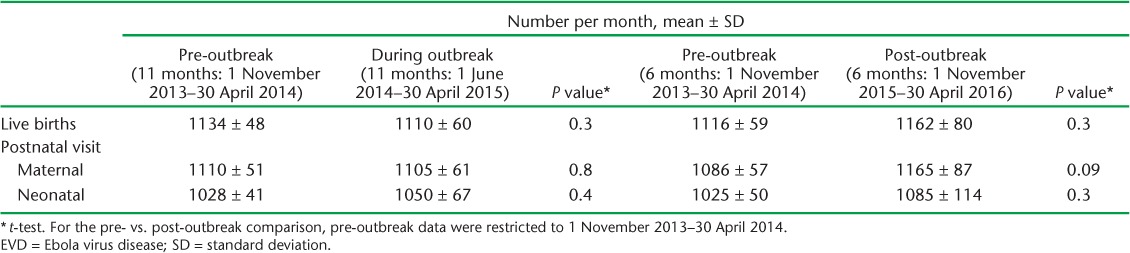

Postnatal care immediately following live birth

There was no significant change in the mean number of live births or PNC1 visits during the study period (Table 4). The high retention of mothers following up at their PNC1 visits after a live birth remained unchanged. The mean number of neonates attending PNC1 was lower than the number of live births across all periods.

TABLE 4.

Number of live births and attendance at first postnatal care visits before, during and after the EVD outbreak in Moyamba District, Sierra Leone

DISCUSSION

Although Sierra Leone has one of the highest global maternal mortality ratios,4 the health system had been making progress in improving outcomes in maternal and childhood mortality before the EVD outbreak through initiatives such as the elimination of user fees for pregnant women and children aged <5 years,16 and the implementation of performance-based health financing.17

Although previous studies had reported that the outbreak had had a significant negative impact on the delivery of health services in this setting,2,3,16–18 no study had previously looked at the spectrum of maternal care through ANC, delivery and PNC, and the impact of the EVD outbreak on programmatic outcomes.

We observed no changes in general trends in women attending ANC1 or ANC4 visits, delivering or attending PNC1 visits, before, during and after the outbreak. There was a significant decrease in the subset of women who attended ANC1 (but not ANC4) outreach visits during the outbreak, with no decrease in facility-based visits, however. The decrease in ANC1 outreach visits may have been due to a decrease in outreach services in general during the outbreak. There was also a delay, until April 2016, before outreach services were resumed in the district. There was a significant decrease in the number of women having community, as opposed to facility-based, deliveries during the outbreak, and a concomitant significant increase in the numbers of deliveries conducted by midwives, with a trend towards a decrease in the number of deliveries performed by maternal child health aides. However, the mean number of deliveries remained unchanged during the outbreak. The increase in facility-based deliveries by skilled health providers may have been because safe deliveries during the outbreak mandated adequate training in appropriate infection prevention and control measures and infrastructure, and provision of PPE.18

Based on previous literature,2,3,16–18 we had expected to find a dramatic change in the utilisation of services during the outbreak. One reason for our study findings showing less change than anticipated could be that in Moyamba District the PHUs remained open, except for the temporary closure of two facilities following infection in a health-care worker. Within the district, the supply chain remained generally intact, salaries were paid, and all primary health-care staff received a financial incentive for EVD work from August 2014 to March 2015. While outreach activities from the PHUs were reduced, as were the routine activities of the community health workers, whose services were diverted to EVD contact tracing, most staff remained active in their health facilities, with the exception of some nurses and community health officers from the district referral hospital, who were deployed to work in an Ebola treatment unit.

Another reason may be that although Moyamba was affected by EVD (211 cases), it did not have as many cases or as prolonged an outbreak as other districts in the country.15 This study did not look at clinical outcomes, only programmatic indicators. In a previous study in three districts in Sierra Leone (Kailahun, Kenema and Port Loko) which had high numbers of EVD cases, there was an average of 22% more maternal deaths and 25% more newborn deaths over the period from May 2014 to April 2015.19

The findings of this study are also in stark contrast to other studies based on programmatic DHIS data in the region,20–23 where facility closures led to up to 80% reductions in recorded services in some instances.20 The authors of these studies postulated a multitude of factors contributing to their findings, including the lack of adequate data reporting, disruption of health services and community fear of contracting EVD at health facilities. The completeness of the data in our study and the consistency in reporting utilisation rates across all study periods may be in part due to the importance of ANC, delivery and postnatal indicators for performance-based financing linked to remuneration within the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation.24 This may act as a behavioural motivation for reporting of data and provision of services. In addition, Moyamba District was the first district in Sierra Leone to start reporting DHIS data using closed user-group mobile phones, which may have improved the quality of the reporting.

The major strength of the study is that the use of data from district-level programme information collected as part of routine monitoring and evaluation from a national public system should be representative of those districts in the region that were less affected by Ebola. The conduct and reporting of the study also adhered to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines and sound ethical principles.25,26 Study limitations include the expected concerns regarding accuracy and consistency associated with the extraction of secondary programmatic data. In addition, while data collection at the PHUs continued, data quality control visits by the District Health Management Team were suspended from June to October 2014 due to repurposing of staff to support the EVD outbreak response. Furthermore, one faith-based health facility and two private hospitals in the district were not captured by the DHIS software. With respect to generalisability, district-level results may also be subject to bias related to district-specific health systems strengthening initiatives, including the presence of partners (e.g., non-governmental organisations) that may have supported maternal and child services during the study period. Finally, DHIS data, which are clinic-based, may introduce selection bias compared to community-based, population-representative sampling, which enables population-wide estimation.26

In conclusion, the present study shows that key primary care programmatic indicators of uptake and utilisation of the continuum of antenatal, delivery and postnatal care for mothers in an EVD-affected rural district in Sierra Leone remained robust despite the outbreak. While the numbers of deliveries remained consistent before, during and after the outbreak, facility-based deliveries increased, suggesting that safe delivery initiatives in the context of an EVD outbreak may affect utilisation of maternity health facilities. Further studies are needed on national and regional programmatic data to look at whether or not these results are generalisable and to examine maternal and newborn outcome indicators. Committed financial investment in strengthening the continuum of maternal care at the primary health care level is critical to maintain resilience in the post-recovery period and beyond.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted through the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT), a global partnership led by the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases at the World Health Organization (WHO/TDR Geneva Switzerland). The training model is based on a course developed jointly by the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union; Paris, France) and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF; Paris, France). The specific SORT IT programme that resulted in this publication was jointly developed and implemented by: WHO/TDR, the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health (Freetown), WHO Sierra Leone (Freetown, Sierra Leone) and the Centre for Operational Research, The Union. Mentorship and the coordination/facilitation of the SORT IT workshops were provided through the Centre for Operational Research, The Union; The Union SouthEast Asia Office, New Delhi, India; the Ministry of Health, Government of Karnataka, Bangalore, India; the Operational Research Unit (LUXOR), MSF, Brussels Operational Centre, Luxembourg; Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH), Eldoret, Kenya; Alliance for Public Health, Kiev, Ukraine; Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium; University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada; Dignitas International, Zomba, Malawi; Partners in Health, Kono, Sierra Leone; and the Baroda Medical College, Vadodara, India. The programme was funded by the Department for International Development (London, UK) and WHO/TDR. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

In accordance with the WHO's open-access publication policy for all work funded by the WHO or authored/co-authored by WHO staff members, the WHO retains the copyright of this publication through a Creative Commons Attribution Intergovernmental Organizations license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/legalcode) which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original work is properly cited.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. . Ebola data and statistics. Situation summary, 11 May 2016. Data published on 11 May 2016. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2016. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.ebola-sitrep.ebola-summary-latest?lang=en. Accessed March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Elston J W, Moosa A J, Moses F, . et al. Impact of the Ebola outbreak on health systems and population health in Sierra Leone. J Public Health 2015. October 27 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bolkan H A, Bash-Taqi D A, Samai M, Gerdin M, von Schreeb J.. Ebola and indirect effects on health service function in Sierra Leone. PLoS Curr 2014; 6 pii: http://currents.plos.org/outbreaks/article/ebola-and-indirect-effects-on-health-service-function-in-sierra-leone/. Accessed March 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Villar J, Ba'aqeel H, Piaggio G, . et al. WHO antenatal care randomised trial for the evaluation of a new model of routine antenatal care. Lancet 2001; 357: 1551– 1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berhan Y, Berhan A.. Antenatal care as a means of increasing birth in the health facility and reducing maternal mortality: a systematic review. Ethiop J Health Sci 2014; 24 Suppl: S93– S104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nour N. An introduction to maternal mortality. Rev Obst Gynecol 2008; 1: 77– 81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization. . Recommendations on postnatal care of the mother and newborn. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization. . Monitoring maternal, newborn and child health: understanding key progress indicators. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Statistics Sierra Leone and ICF International. . Sierra Leone Demographic and Health Survey 2013: key findings. Rockville, MD, USA: Statistics Sierra Leone and ICF International, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10. MacKinnon J, MacLaren B.. Human resources for health challenges in fragile states. Evidence from Sierra Leone, South Sudan and Zimbabwe. Ottawa, ON, Canada: The North-South Institute, 2012. http://www.nsi-ins.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/2012-Human-Resources-for-Health-Challenges-in-Fragile-States.pdf. Accessed March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. . Recommendations for managing and preventing cases of malaria in areas with Ebola. Atlanta, GA, USA: CDC, 2015. www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/malaria-cases.html. Accessed March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dynes M, Tamba S, Vandi M A, Tomczyk B.. Perceptions of the risk for Ebola and health facility use among health workers and pregnant and lactating women—Kenema District, Sierra Leone, September 2014. MMWR 2015; 63: 1226– 1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. United Nations Development Programme. . Human Development Report 2015. New York, NY, USA: UNDP, 2015. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/all/themes/hdr_theme/country-notes/SLE.pdf. Accessed March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ministry of Health and Sanitation, Sierra Leone. . Sierra Leone basic package of essential health services, 2015–2020. Freetown, Sierra Leone: MoHS, 2017. http://www.mamaye.org.sl/en/evidence/sierra-leone-basic-package-essential-health-services-2015-2020. Accessed March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moyamba District Health Office, Ministry of Health and Sanitation, Sierra Leone. . Moyamba District. Daily EVD situation report viral hemorrhagic fever database. Moyamba, Sierra Leone: Moyamba District Health Office, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Witter S, Wurie H, Bertone M P.. The free health care initiative: how has it affected health workers in Sierra Leone? Health Policy Plan 2015; 31: 1– 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bertone M P, Lagarde M, Witter S.. Performance-based financing in the context of the complex remuneration of health workers: findings from a mixed-method study in rural Sierra Leone. BMC Health Serv Res 2016; 16: 286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. World Health Organization, United Nations Children's Fund & Save the Children. . A guide to the provision of safe delivery and immediate newborn care in the context of an Ebola outbreak. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ministry of Health and Sanitation. . Rapid assessment of Ebola impact on reproductive health services and services seeking behavior in Sierra Leone. Freetown, Sierra Leone: Government of Sierra Leone, Department for International Department, Irish Aid & United Nations Population Fund, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Iyengar P, Kerber K, Howe C J, Dahn B.. Services for mothers and newborns during the Ebola outbreak in liberia: the need for improvement in emergencies. PLOS Curr 2015; 16: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lori J R, Rominski S D, Perosky J E, . et al. A case series study on the effect of Ebola on facility-based deliveries in rural Liberia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015; 15: 254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Delamou A, Hammonds R M, Caluwaerts S, Utz B, Delvaux T.. Ebola in Africa: beyond epidemics, reproductive health in crisis. Lancet 2014; 384: 2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brolin Ribacke K J, van Duinen A J, Nordenstedt H, . et al. The impact of the West Africa Ebola outbreak on obstetric health care in Sierra Leone. PLOS ONE 2016; 11: e0150080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cordaid. . External verification performance based financing in healthcare in Sierra Leone. The Hague, The Netherlands: Cordaid, 2014. https://www.cordaid.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2014/12/PBF-external_verification_main_report_Cordaid_Layout_15062014.pdf Accessed April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25. von Elm E, Altman D G, Egger M, . et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007; 370: 1453– 1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Edginton M, Enarson D, Zachariah R, . et al. Why ethics is indispensable for good-quality operational research. Public Health Action 2012; 2: 21– 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ly J, Sathananthan V, Griffiths T, . et al. Facility-based delivery during the Ebola virus disease epidemic in rural Liberia: analysis from a cross-sectional, population-based household survey. PLOS Med 2016; 13: e1002096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]