Abstract

Objective:

To determine whether common genetic variants in UNC5C, a recently identified late-onset Alzheimer disease (LOAD) dementia susceptibility gene, are associated with AD susceptibility or AD-related clinical/pathologic phenotypes.

Methods:

We used data from deceased individuals of European descent who participated in the Religious Orders Study or the Rush Memory and Aging Project (n = 1,288). We examined whether there were associations between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within ±100 kb of the UNC5C gene and a diagnosis of AD dementia, global cognitive decline, a pathologic diagnosis of AD, β-amyloid load, neuritic plaque count, diffuse plaque count, paired helical filament tau density, neurofibrillary tangle count, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) score. We also evaluated the relation of the CAA-associated variant and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) UNC5C RNA expression. Secondary analyses were performed to examine the interaction of the CAA-associated SNP and known genetic risk factors of CAA as well as the association of the SNP with other cerebrovascular pathologies.

Results:

A set of UNC5C SNPs tagged by rs28660566T was associated with a higher CAA score (p = 2.3 × 10−6): each additional rs28660566T allele was associated with a 0.60 point higher CAA score, which is equivalent to approximately 75% of the higher CAA score associated with each allele of APOE ε4. rs28660566T was weakly associated with lower UNC5C expression in the human DLPFC (p = 0.036). Moreover, rs28660566T had a synergistic interaction with APOE ε4 on their association with higher CAA severity (p = 0.027) and was associated with more severe arteriolosclerosis (p = 0.0065).

Conclusions:

Targeted analysis of the UNC5C region uncovered a set of SNPs associated with CAA.

A recent study reported the association of UNC5C T835M (rs137875858A), a rare coding variant in this netrin receptor implicated in axon guidance during development,1 with late-onset Alzheimer disease (LOAD).2 As we have shown in our study of the TREM locus,3 multiple genetic variants in the same locus can have independent effects on disease susceptibility and could affect specific features of the disease. We, therefore, assessed whether common UNC5C variants influence AD-related cognitive and pathologic phenotypes in 2 large clinical pathologic cohort studies of aging and dementia. We found a set of UNC5C single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in a single linkage disequilibrium (LD) block linked to the severity of cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), a disease of small cerebral arterioles caused by β-amyloid accumulation.4

METHODS

Subjects, standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

Our subjects were from 2 large community-based cohort studies of older adults, the Religious Orders Study (ROS) and the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP).5,6 Both studies enroll older adults without known dementia, and each participant signed written informed consent and Anatomical Gift Act. All study steps were done in compliance with the protocol approved by the Rush University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Overall follow-up rate and autopsy rate for deceased individuals were greater than 85%. Of note, these 2 cohorts were designed to be used in combined analyses: ROS and MAP were designed and managed by the same team of investigators at the Rush Alzheimer's Disease Center and captured shared phenotypic measures. We limited our analyses to deceased European-descent individuals with quality-controlled genome-wide genotyping data and completed autopsy (February 2016 Data Freeze, total n = 1,288).

Cognitive and pathologic phenotypes.

Nine AD-related cognitive and pathologic variables (diagnosis of AD dementia, global cognitive decline, pathologic diagnosis of AD, β-amyloid load, neuritic plaque count, diffuse plaque count, paired helical filament tau [PHFtau] density, neurofibrillary tangle count, and the CAA score) were defined as previously described.3,5–7 Square-root transformed values were used for analyses of continuous pathologic variables (β-amyloid load, neuritic plaque count, diffuse plaque count, PHFtau density, and neurofibrillary tangle count) to account for their positively skew deviation, as previously described.3 CAA was graded on a 5-point scale (0–4) in 4 neocortical regions (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [DLPFC], angular gyrus, inferior temporal gyrus, and calcarine cortex) and averaged to derive a CAA score (0–4).7 Of note, among the 1,288 subjects in this study, numbers of subjects with measured values for each phenotype, who were included in each analysis, were as follows: diagnosis of AD dementia (n = 1,257), global cognitive decline (n = 1,193), pathologic diagnosis of AD (n = 1,140), β-amyloid load (n = 1,095), neuritic plaque count (n = 1,132), diffuse plaque count (n = 1,132), PHFtau density (n = 1,088), neurofibrillary tangle count, (n = 1,132), and CAA score (n = 1,107).

For secondary analyses, atherosclerosis, arteriolosclerosis, gross infarcts, and microinfarcts are measured as previously described.8 In brief, atherosclerosis was assessed by visual inspection at the circle of Willis, and the severity was semiquantitatively graded (scale from 0 to 6), which was collapsed into 4 levels (none/possible, mild, moderate, and severe) for analysis. Arteriolosclerosis was microscopically evaluated in anterior basal ganglia with a semiquantitative scale (0–7), which was collapsed into 4 levels (none, mild, moderate, and severe) for analysis. Gross infarcts and microinfarcts were recorded as present vs absent. Among the 1,288 subjects in this study, numbers of subjects with measured values for each phenotype, who were included in each analysis, were as follows: atherosclerosis (n = 1,141), arteriolosclerosis (n = 1,130), gross infarcts (n = 1,136), and microinfarcts (n = 1,136).

Genotyping and RNA-Seq data acquisition and processing.

Genome-wide genotyping (on either Affymetrix GeneChip 6.0 or Illumina OmniQuad Express), quality control (QC), and imputation were performed as previously described.3 Genotype QC was done with PLINK software version 1.08,9 and the metrics included a genotype success rate of >95%, Hardy-Weinberg p > 0.001, and a misshap test of <1 × 10−9. Closely related individuals are removed with Pihat method using PLINK. EIGENSTRAT (default setting)10 was used to generate a genotype covariance matrix, and population outliers were removed. Then, genotype imputation was done with BEAGLE software (version 3.3.2)11 on a reference map from 1,000 Genomes Project Consortium interim phase I haplotypes (2010–2011 data freeze). Imputed genotypes with a minor allele frequency (MAF) of >0.01 and an INFO score of >0.3 were used in this analysis. We defined the UNC5C region as the chromosomal segment containing the transcribed elements of UNC5C and ±100 kb of flanking DNA (chr4: 95,983,655-96,570,361 on hg19 build), which contained 2,269 1000 Genomes Project reference SNPs. Of note, APOE genotypes were measured through a separate sequencing procedure as previously described,5,6 and APOE ε2 and ε4 allele counts were used in this study. RNA was extracted from frozen postmortem DLPFC from a subset of participants and was quantified using next-generation quantitative RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq). QC and quantile normalization of RNA-Seq Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped (FPKM) values for UNC5C were done as previously described,12 and 494 subjects in our study had nonmissing values.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed with R 3.2.1 (r-project.org), and we combined ROS and MAP in all our analyses, unless otherwise specified. To derive the number of independent genetic markers tested in this study, we used LD-based SNP pruning (with an r2 threshold of 0.2, a window of 50 SNPs, and a step of 5 SNPs), done with PLINK, as previously published.3 This procedure yielded 391 independent LD blocks within the UNC5C region. As we tested for 9 traits, Bonferroni-adjusted α for the primary analysis was α = 1.4 × 10−5 (0.05 ÷ [391 × 9]). Assuming additive genetic effects, logistic regression models were used for dichotomous outcome variables (AD dementia and pathologic AD), and linear regression models were used for others, with covariates including age at death, sex, cohort (ROS vs MAP), and the first 3 principal components from the genotype covariance matrix derived with EIGENSTRAT. Years of education was also included as a covariate in the analyses of phenotypes affected by cognitive performance (AD dementia and global cognitive decline). Results from 2 genotyping platforms were calculated separately and meta-analyzed with PLINK, and the consistencies across genotyping platforms were examined with meta-analyses I2 values.13 The results were plotted using LocusZoom,14 with chromatin state tracks predicted by the ChromHMM core 15-chromatin state model15 from the Roadmap Epigenomics Project.16

For SNPs associated with a trait (CAA), we looked up the LD r2 values between the lead SNP and all other identified SNPs in the HaploReg database17 and also analyzed each of the other SNPs in a same linear model with the lead SNP to examine whether they represent a different LD block or not. The population variance explained by the lead SNP was derived from a sequential adjusted R-squared analysis with linear models: We first calculated the adjusted R-squared from a linear model to explain the trait of interest with age at death, sex, study cohort, genotyping platform, and first 3 principal components from the genotype covariance matrix. Then, we included the lead SNP's minor allele dosage in the model and calculated the increment of the adjusted R-squared. The population variance explained by the SNP was then compared with that of APOE ε4.

To further evaluate the functional significance of the LD block associated with increased CAA severity, we examined the predicted chromatin state (per the ChromHMM core 15-chromatin state model from the Roadmap Epigenomics Project15,16) of each SNP associated with CAA severity. Then, the lead SNP was tested for the association with the UNC5C RNA level in a linear model, controlling for age at death, sex, study cohort, genotyping platform, first 3 principal components from the genotype covariance matrix, and technical covariates (RNA integrity score, log2(total aligned reads), postmortem interval, and number of ribosomal bases). Then, the UNC5C RNA level was tested for its association with CAA severity, controlling for the same set of covariates.

In addition, to test whether the association between the identified UNC5C variant and CAA is independent of known genetic risk factors for CAA (APOE ε4, ε2, and CR1 rs6656401A),18 each of the previously reported genetic risk factors was added to the linear model testing association between the UNC5C variant and the CAA score. Interaction between the UNC5C variant and a previously reported genetic risk factor was checked using the product term in the linear regression model, if the association of the UNC5C variant and the CAA score attenuated after including that known genetic risk factor in the model. After the statistical interaction was found, stratified analysis was done to further test the relationship between 2 genetic risk factors. Of note, we assumed an additive effect of CAA severity by APOE ε4, ε2, or CR1 rs6656401A in our models.

Further exploratory analyses were performed to interrogate the association of the identified UNC5C CAA variant and cerebrovascular pathology. Ordinal logistic regression models were used for the ordered categorical variables (atherosclerosis and arteriolosclerosis), and logistic regression models were used for the binary variables (gross infarct and microinfarct). Age at death, sex, study cohort, genotyping platform, and first 3 principal components from the genotype covariance matrix were included as covariates for each analysis. p values were Bonferroni adjusted for multiple comparisons (number of testing = 4 for these targeted exploratory analyses).

Finally, the sample size required to reproduce our result was calculated with the Genetic Power Calculator, assuming an additive model and a similar effect size.19

RESULTS

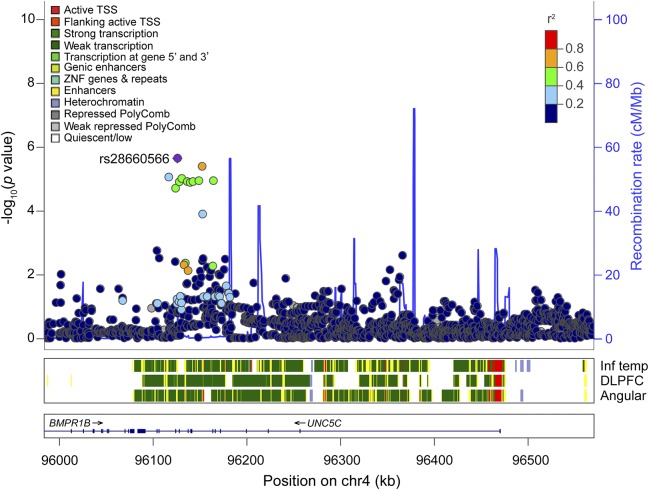

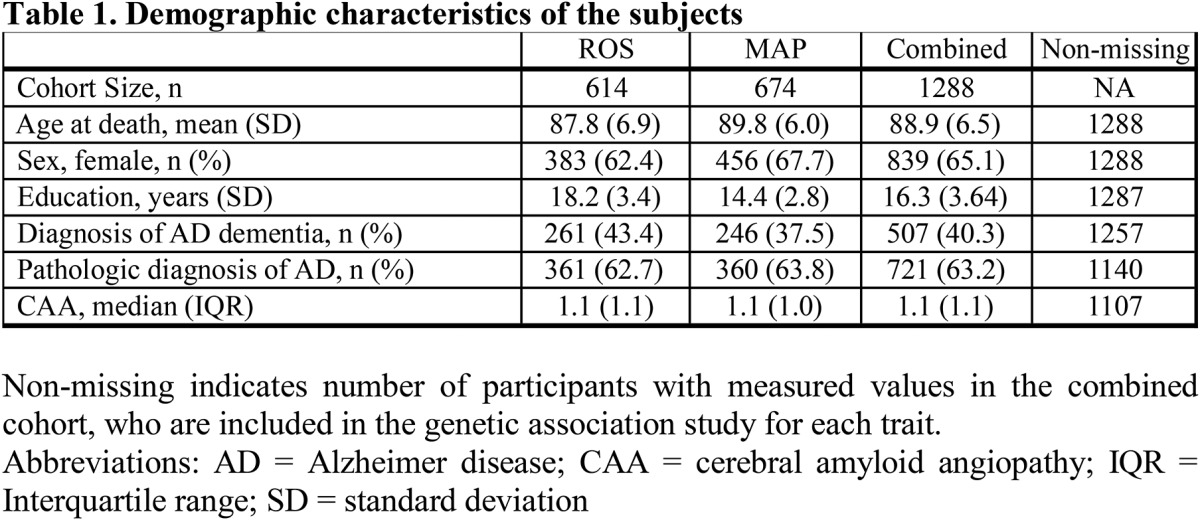

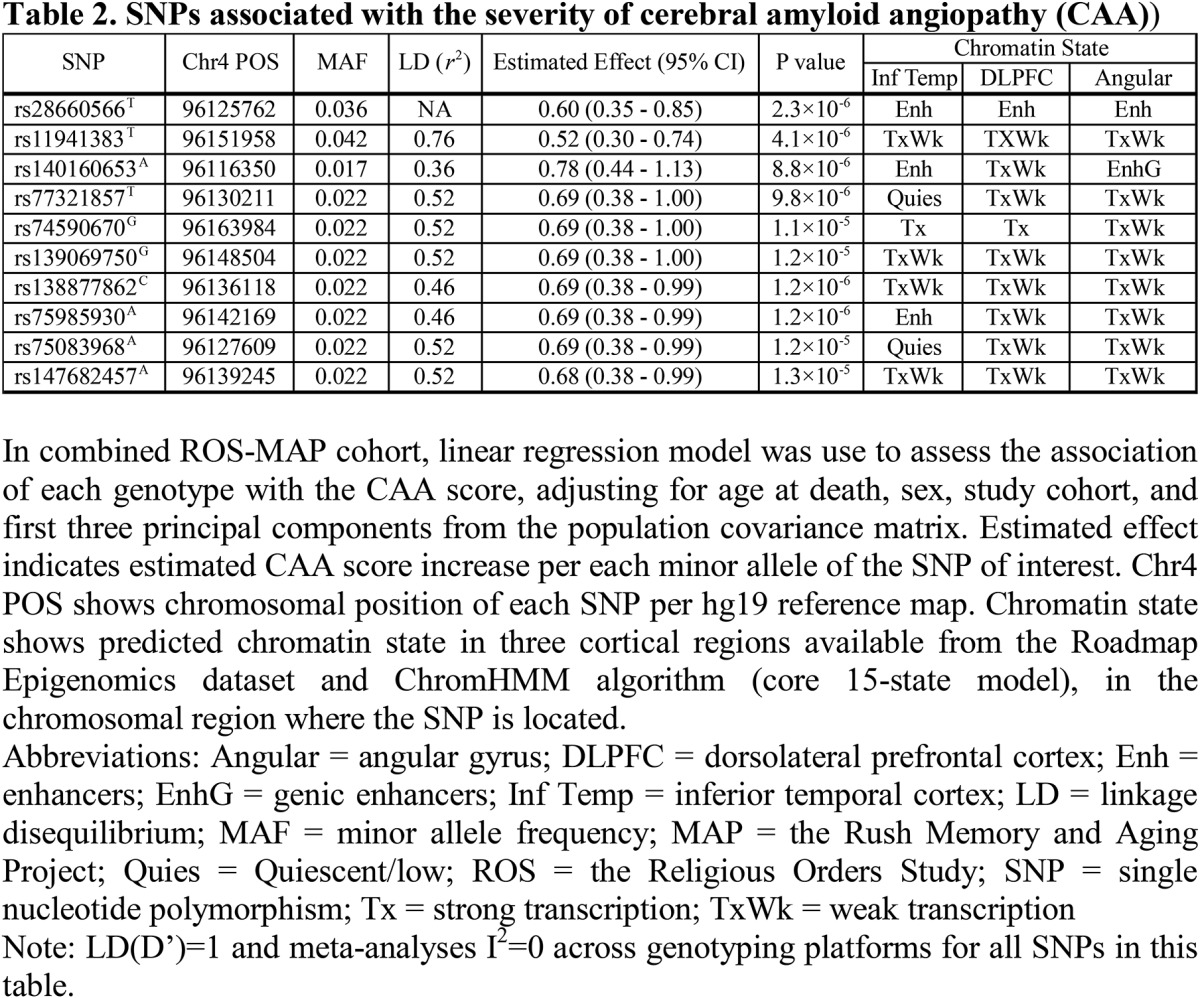

Demographic characteristics of the subjects are summarized in table 1. The total number of subjects analyzed in this study was n = 1,288. Among the subjects, 1,114 were genotyped with Affymetrix GeneChip 6.0, and 174 were genotyped with Illumina OmniQuad Express. In our primary analyses using additive models, 10 UNC5C intronic SNPs were associated with a higher CAA score (p < 1.4 × 10−5) (figure 1 and table 2). All 10 SNPs were imputed SNPs with good imputation quality (INFO score >0.89; table e-1 at Neurology.org/ng), and the association was consistent across genotyping platforms, shown by meta-analysis I2 = 0 for all 10 SNPs. No other associations are found between UNC5C variants and other tested AD-related traits (p > 5.0 × 10−4 for all other trait-SNP pairs, well above the threshold type I error rate of this study; figure e-1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the subjects

Figure 1. Regional association plot of the CAA score in the UNC5C region.

Regional association plots of CAA in UNC5C ±100 kb. X-axis denotes chromosomal location on chromosome 4, and Y-axis denotes negative log of the p value of the association between the SNP and the CAA score, adjusting for age at death, sex, study cohort, and first 3 principal components from the genetic covariance matrix. Each point corresponds to each SNP, and the color of each point indicates linkage disequilibrium r2 value between each SNP of interest and rs28660566T. Blue line in the graph represents recombination rate in cM/Mb. The color-coded tracks below the association plot show predicted functional chromatin states in inferior temporal cortex (Inf Temp), DLPFC, and angular gyrus cortex (angular), derived from the Roadmap Epigenomics project. CAA = cerebral amyloid angiopathy; DLPFC = dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; TSS = transcription start site; ZNF = zinc finger. The track below the predicted chromatin states shows the location of genes: the thick line is exon, and the thin line is intron.

Table 2.

SNPs associated with the severity of CAA

The top CAA risk allele rs28660566T (MAF = 3.6%) was in LD with the other 9 identified SNPs (r2 ≥ 0.36, D′ ≥ 0.93; table 2). To rule out their effect independent of rs28660566T, each of the 9 SNP dosages was tested in a same linear additive model with rs28660566T, and none were associated with the CAA score when adjusted for rs28660566T (p > 0.05). Thus, rs28660566T tags all other SNPs associated with a higher CAA score, and this LD block defines a chromosomal segment containing several UNC5C exons (figure 1). In the linear model, the presence of an rs28660566T allele corresponded to a 0.60-point higher CAA score, which is approximately 75% of the effect size of an APOE ε4 allele on this trait (estimated effect 0.80, p = 1.5 × 10−38). The UNC5C variant therefore has a large effect, but rs28660566T (MAF 3.6%) explained approximately only 1.9% of the population variance given its low MAF, whereas APOE ε4 (MAF 13.8%) explained approximately 13.1% of the population variance. Of note, rs28660566T dosage was not associated with parenchymal β-amyloid load (p = 0.80).

The predicted chromatin state of a given chromosomal segment (table 2 and figure 1) can be helpful in inferring its functional implications (e.g., enhancer, promoter, etc.). The lead SNP rs28660566T was within a chromosomal region identified as an enhancer in multiple brain regions, suggesting that this region may have a regulatory role. None of the other identified SNPs were in the regulatory chromosomal region in the DLPFC. Of interest, rs28660566T dosage was nominally associated with decreased UNC5C mRNA expression in the DLPFC (estimated effect −0.097, 95% confidence interval [CI] −0.19 to −0.0063, p = 0.036), but the DLPFC UNC5C mRNA expression level was not associated with the CAA score (p = 0.75).

APOE ε4, ε2, and CR1 rs6656401A have been previously reported to be associated with higher odds and/or severity of CAA.18 The association between rs28660566T and the CAA score was attenuated by approximately 13% when the APOE ε4 allele count was included in the model (estimated effect 0.52, 95% CI 0.29–0.75, p = 1.2 × 10−5). In fact, a statistical interaction between APOE ε4 allele count and rs28660566T dosage on the CAA score was present, suggesting a synergistic effect modification between these 2 genetic risk factors (estimated effect 0.44, 95% CI 0.049–0.84, p = 0.027). In a stratified analysis, the association between rs28660566T dosage and the CAA score was weaker in a subgroup with no APOE ε4 allele (n = 822, estimated effect 0.38, 95% CI 0.12–0.64, p = 0.0046) compared with the association in a subgroup with 1 or 2 APOE ε4 alleles (n = 285, estimated effect 1.00, 95% CI 0.50–1.50, p = 1.2 × 10−4). By contrast, the association between rs28660566T and the CAA score did not change by adding APOE ε2 or CR1 rs6656401A in the model (with APOE ε2: estimated effect 0.60; 95% CI 0.35–0.85; p = 2.0 × 10−6, with rs6656401A: estimated effect 0.60; 95% CI 0.35–0.85; p = 2.3 × 10−6).

In an additional exploratory analysis to test whether rs28660566T alters the relationship between parenchymal β-amyloid load and the CAA score, we found no statistically significant interaction between rs28660566T and parenchymal β-amyloid load on their associations with the CAA score (p = 0.42). Then, we also explored whether rs28660566T was associated with other cerebrovascular pathologies (Bonferroni-corrected p value threshold 0.0125): rs28660566T was associated with increased odds of more severe arteriolosclerosis (odds ratio [OR] 1.8; 95% CI 1.2–2.8; p = 0.0065) but not with atherosclerosis (OR 1.6; 95% CI 1.1–2.4; p = 0.023), gross infarcts (p = 0.54), or microinfarcts (p = 0.69).

Finally, we calculated the sample size required to replicate our result with the Genetic Power Calculator,19 assuming a similar effect size. Assuming an additive model with 4% of MAF, 389 subjects are needed to detect 2% of total population variance with a type I error rate of 0.05 and power of 80%.

DISCUSSION

Targeted analysis of the chromosomal region of UNC5C, a recently identified AD susceptibility gene, uncovered a possible new risk locus associated with CAA severity, which comprises a single LD block captured by rs28660566T. Of interest, rs28660566T synergistically interacts with APOE ε4 to increase CAA severity, suggesting a possibility of a common downstream pathway.

In a recent study reporting the association of a rare UNC5C coding variant rs137875858A (UNC5C T835M) with LOAD, the authors showed that UNC5C T835M exerts its effect through increased neuronal vulnerability rather than increased amyloid or tau production.2 Consistent with this report, no common UNC5C variant was associated with parenchymal β-amyloid or PHFtau accumulation in our study. Thus, the association of UNC5C rs28660566T with CAA is more likely to be mediated by ineffective perivascular β-amyloid drainage rather than increased neuronal β-amyloid production. Of interest, rs28660566T was also associated with arteriolosclerosis, a disease of small deep cerebral arterioles, suggesting an implication of UNC5C in arteriolar susceptibility to pathologic changes, not only limited to vascular β-amyloid deposition. In fact, a previous study reported that UNC5C is expressed in endothelial cells, and inhibition of UNC5C attenuated netrin-1 effect on in vitro endothelial cell migration,20 suggesting a potential role of UNC5C in vascular development and maintenance.

The functional mechanism of the UNC5C CAA severity risk locus remains to be determined. The lead SNP, rs28660566T, is located within a predicted enhancer chromosomal locus in multiple brain regions,15,16 and in our study, it was a weak eQTL associated with lower UNC5C mRNA expression in the DLPFC. However, the DLPFC UNC5C mRNA level was not associated with CAA severity. Nonetheless, our DLPFC RNA-Seq data lack cell-type specific information and might not capture differential expression limited to certain tissue types such as arterioles. As CAA is a disease primarily of small cortical and leptomeningeal arterioles,4 gene expression profiles from isolated leptomeningeal and cortical arterioles might be necessary to further dissect the mechanisms of UNC5C in CAA progression.

Of note, the previously reported UNC5C T835M variant (chromosome 4, position 96,091,431) is 34.3 kb away from rs28660566T, and it is not included in the chromosomal segment defined by the LD block captured by rs28660566T. UNC5C T835M might be on a same haplotype with rs28660566T, given the low recombination frequency between the 2 loci (figure 1), but we cannot confirm this in ROS-MAP participants because the sequencing of the UNC5C region is not yet available. However, given the rarity of T835M (MAF <0.1%), it is very unlikely that the observed association is driven by UNC5C T835M in our subject population (n = 1,107 for the CAA analysis). We also note that rs28660566T is not in LD with rs3846455G (237.3 kb apart from rs28660566T), an UNC5C allele that we have recently reported to be associated with worse late-life cognition, when adjusted for the burden of multiple neuropathologies (including CAA) and demographics.21 Thus, there are both allelic and phenotypic heterogeneity within the UNC5C locus, similar to our previous findings in the TREM locus.3

The study is methodologically robust. The analyses are performed on more than 1,100 participants from 2 community-based cohort studies, with a semiquantitative assessment of CAA severity in multiple cortical regions. We performed a targeted gene analysis of UNC5C, and a set of UNC5C variants showed significant association with the CAA severity after rigorously correcting for the number of hypotheses tested. Moreover, the result was consistent across 2 genotyping platforms. Validation efforts with independent data sets are essential to extend the evaluation of this risk locus, and close to 400 subjects with pathologic assessment of CAA in multiple cortical areas are required to replicate our findings with type 1 error rate of 0.05 and power of 80%. In addition, experimental studies would be essential to understand the underlying biological mechanisms. In conclusion, we found an UNC5C variant to be associated with CAA severity, and additional studies are required to clarify the role of UNC5C in CAA pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the study participants. More information regarding obtaining (ROS/MAP/ROS and MAP) data for research use can be found at the RADC Research Resource Sharing Hub (radc.rush.edu).

GLOSSARY

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- CAA

cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- CI

confidence interval

- DLPFC

dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

- LD

linkage disequilibrium

- LOAD

late-onset Alzheimer disease

- MAF

minor allele frequency

- MAP

Rush Memory and Aging Project

- OR

odds ratio

- PHFtau

paired helical filament tau

- QC

quality control

- RNA-Seq

RNA-sequencing

- ROS

Religious Orders Study

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org/ng

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Hyun-Sik Yang and Charles C. White: drafting/revising the manuscript for content, study concept or design, statistical analysis, and analysis or interpretation of data. Lori B. Chibnik: drafting/revising the manuscript for content, study concept or design, and analysis or interpretation of data. Hans-Ulrich Klein: drafting/revising the manuscript for content and analysis or interpretation of data. Julie A. Schneider and David A. Bennett: drafting/revising the manuscript for content, analysis or interpretation of data, acquisition of data, and obtaining funding. Philip L. De Jager: drafting/revising the manuscript for content, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, acquisition of data, study supervision, and obtaining funding.

STUDY FUNDING

The study was funded by NIH grants P30AG10161, R01AG17917, R01AG036836, RF1AG15819, and U01AG046152.

DISCLOSURE

H.-S. Yang has received research support from Alzheimer's Association Clinical Fellowship. C.C. White reports no disclosures. L.B. Chibnik has received research support from NIH/NIA. H.-U. Klein reports no disclosures. J.A. Schneider has served on scientific advisory boards for Alzheimer's Association, Fondation Plan Alzheimer (France), the Dutch CAA Foundation, University of Washington/Group Health Alzheimer's Disease Patient Registry/Adult Changes in Thought study, New York University, AVID Radiopharmaceuticals, Genentech, Grifols, and Eli Lilly; has served on the editorial boards of the Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry and the Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology; has been a consultant for AVID Radiopharmaceuticals, Navidea Biopharmaceuticals Inc., the Michael J. Fox Foundation, National Football League, and National Hockey League; has received research support from AVID Radiopharmaceuticals, NIH, and NIA; and has taken part in legal proceedings involving National Football League, National Hockey League, and World Wrestling Entertainment. D.A. Bennett has served on scientific advisory boards for Vigorous Minds, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and AbbVie; has served on the editorial boards of Neurology, Current Alzheimer Research, and Neuroepidemiology; and has received research support from NIH. P.L. De Jager has served on scientific advisory boards for TEVA Neuroscience, Genzyme/Sanofi, and Celgene; has received speaker honoraria from Biogen Idec, Source Health care Analytics, Pfizer Inc., and TEVA; has served on the editorial boards of the Journal of Neuroimmunology, Neuroepigenetics, and Multiple Sclerosis; and has received research support from Biogen, Eisai, UCB, Pfizer, Sanofi/Genzyme, NIH, NIA, and the National MS Society. Go to Neurology.org/ng for full disclosure forms.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leonardo ED, Hinck L, Masu M, Keino-Masu K, Ackerman SL, Tessier-Lavigne M. Vertebrate homologues of C. elegans UNC-5 are candidate netrin receptors. Nature 1997;386:833–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wetzel-smith MK, Hunkapiller J, Bhangale TR, et al. A rare mutation in UNC5C predisposes to late-onset Alzheimer's disease and increases neuronal cell death. Nat Med 2014;20:1452–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Replogle JM, Chan G, White CC, et al. A TREM1 variant alters the accumulation of Alzheimer-related amyloid pathology. Ann Neurol 2015;77:469–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charidimou A, Gang Q, Werring DJ. Sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy revisited: recent insights into pathophysiology and clinical spectrum. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012;83:124–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the Religious Orders Study. Curr Alzheimer Res 2012;9:628–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Boyle PA, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the rush Memory and aging project. Curr Alzheimer Res 2012;9:646–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyle PA, Yu L, Nag S, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cognitive outcomes in community-based older persons. Neurology 2015;85:1930–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arvanitakis Z, Capuano AW, Leurgans SE, Buchman AS, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. The relationship of cerebral vessel pathology to brain microinfarcts. Brain Pathol 2017;27:77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 2007;81:559–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 2006;38:904–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Browning BL, Browning SR. A unified approach to genotype imputation and haplotype-phase inference for large data sets of trios and unrelated individuals. Am J Hum Genet 2009;84:210–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan G, White CC, Winn PA, et al. CD33 modulates TREM2: convergence of Alzheimer loci. Nat Neurosci 2015;18:1556–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics 2010;26:2336–2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ernst J, Kellis M. ChromHMM: automating chromatin-state discovery and characterization. Nat Methods 2012;9:215–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roadmap Epigenomics C, Kundaje A, Meuleman W, et al. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature 2015;518:317–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward LD, Kellis M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40:D930–D934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biffi A, Shulman JM, Jagiella JM, et al. Genetic variation at CR1 increases risk of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology 2012;78:334–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Purcell S, Cherny SS, Sham PC. Genetic Power Calculator: design of linkage and association genetic mapping studies of complex traits. Bioinformatics 2003;19:149–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lejmi E, Leconte L, Pedron-Mazoyer S, et al. Netrin-4 inhibits angiogenesis via binding to neogenin and recruitment of Unc5B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008;105:12491–12496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White CC, Yang HS, Yu L, et al. Identification of genes associated with dissociation of cognitive performance and neuropathological burden: Multistep analysis of genetic, epigenetic, and transcriptional data. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.