Abstract

Background Central and perpendicular (PERP) screw orientations have each been described for scaphoid fracture fixation. It is unclear, however, which orientation produces greater compression.

Questions/Purposes This study compares compression in scaphoid waist fractures with screw fixation in both PERP and pole-to-pole (PTP) configurations. PERP orientation was hypothesized to produce greater compression than PTP orientation.

Methods Ten preoperative computed tomography scans of scaphoid waist fractures were classified by fracture type and orientation in the coronal and sagittal planes. Three-dimensional models of each scaphoid and fracture plane were created. Simulated Acutrak 2 (Acumed, Hillsboro, OR) screws were placed into the models in both PERP and PTP orientations. Engagement length and screw angle relative to the fracture were measured. Compression strength was calculated from the shear area, average density, and angle acuity.

Results The PTP angle between screw and fracture ranged from 36 to 84 degrees. By definition, the PERP screw-to-fracture angle was 90 degrees. Perpendicularity of the PTP screw to the fracture was positively correlated to compression strength. PERP screws had greater compression than PTP screws when the PTP screw-to-fracture angle was < 80 degrees (106 vs. 80 N), but there was no difference in compression when the PTP screw-to-fracture angle was > 80 degrees, approximating the PERP screw.

Conclusion Increasing screw perpendicularity resulted in higher compression when the screw-to-fracture angle of the PTP screw was < 80 degrees. Maximum compression was obtained with a screw PERP to the fracture. The increased compression gained from PERP screw placement offsets the decreased engagement length.

Clinical Relevance These results provide guidelines for optimal screw placement in scaphoid waist fractures.

Keywords: scaphoid, fracture, compression, screw fixation

There are conflicting opinions in regard to the ideal screw orientation in scaphoid fracture fixation. Proponents of central axis screw placement cite greater stability with longer screws and increased screw threads across the fracture site. 1 2 3 In contrast, others tout the biomechanical advantage of perpendicular (PERP) screws in producing greater stability 4 as well as possible improved ease of screw insertion, 5 use of a shorter screw, 6 and increased surface area for bony bridging. 7

No studies have looked at compression specifically in regard to screw orientation, though the importance of compression in scaphoid fracture fixation is well appreciated. Compression leads to bony apposition, construct rigidity, and stability. Compression is of further importance considering that union of scaphoid fractures relies on primary bone healing, as callus is not tolerated due to the near circumferential articular surface of the scaphoid. 8 The importance of this is illustrated in the numerous studies that have been performed to determine the ideal scaphoid screw type based on compression profiles. 7 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

In light of the importance of compressive fixation and unknown ideal screw orientation, we aimed to evaluate compression in scaphoid waist fractures with screw fixation in both PERP and pole-to-pole (PTP) (central axis) configurations. We hypothesized that PERP screw orientation in scaphoid waist fracture fixation produces greater compression than PTP orientation.

Materials and Methods

The study was approved by our institution's Institutional Review Board. Ten preoperative computed tomography (CT) scans of scaphoid waist fractures were identified and classified by fracture type and orientation in both the coronal and sagittal planes.

Scaphoid Modeling

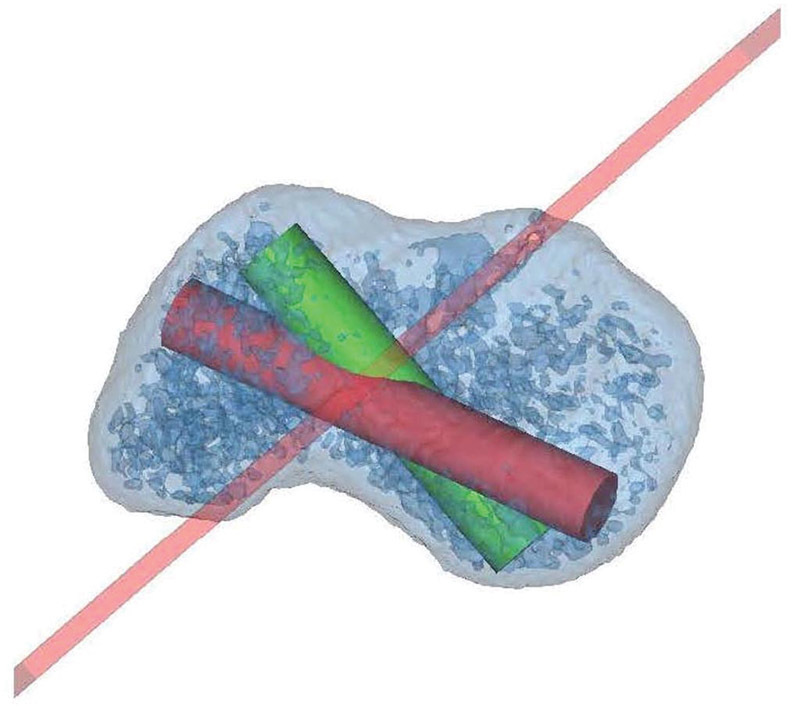

Proximal and distal poles were indicated using the in-line scaphoid CT reconstruction. Three-dimensional models of each scaphoid were created and Mimics (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) software was used to segment out the scaphoid, calculate the fracture plane, and position the screw models. Simulated Acutrak 2 Mini (Acumed, Hillsboro, OR) 3.5 mm screws were placed into the scaphoid models in both PERP and PTP orientations. Geomagic software (3D Systems, Rock Hill, SC) was used to output data from Mimics. PTC Creo (PTC, Needham, MA) software was used to model the screws and to calculate the engagement length and screw angle ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Simulation model of a transverse scaphoid waist fracture. The fracture plane is indicated by the red line. The red cylinder represents the pole-to-pole screw and the green cylinder represents the perpendicular screw.

Compression Calculation

The compressive force of the screw is dependent on the shear strength of bone and the thread shear area of the screw. 19 The shear strength of bone can be calculated given its relationship to bone density. 19 Hounsfield units (HU) were converted to density (g/cm 3 ) using the Crookshank et al conversion (ρ = HU/1.333–22.806). 20 An average value of 400 HU was used for each sample based on the average value of bone density found in the area around the screw in our cohort. Shear strength (MPa) of bone was then calculated using the following formula 21 :

Shear strength = 21.6 × ρ1.65

The thread shear area is the total area of bone that the screw threads engage. It is dependent on the outer diameter (mm) of the screw and the engagement length (mm) of the screw. To determine the engagement of the length of the screw, the PTP distance and the maximum distance PERP to the fracture plane from proximal to distal were both measured. These distances were used to maximize the length of the screw in each orientation. Screws were placed so that no part of the screw extruded through the cortex and the engagement length was measured. Assumptions of 100% thread engagement along the length of the screw and half of the diameter of the screw engaging bone were made to calculate the thread shear area (mm 2 ) using the following formula:

Thread shear area = 1/2 × π × screw diameter × engagement length

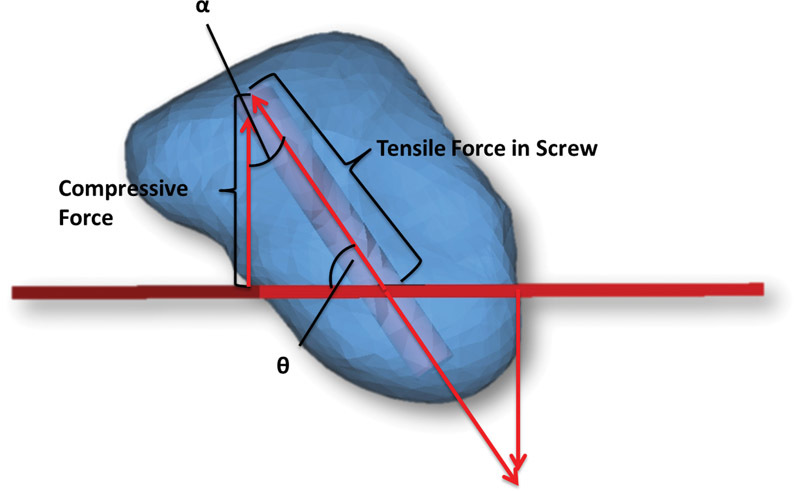

The screw angle relative to the fracture, θ (degrees), was then measured between the fracture plane and the long axis of the screw. The compressive force (N) is the normal force PERP to the fracture plane. By measuring θ, the angle between the compressive force and the hypotenuse (tensile force), α, can be found by subtracting θ from 90 degrees ( Fig. 2 ). The angle measurements were converted to radians. Uniform bone density was assumed throughout the engagement length of the screw. A trigonometric relationship was used to calculate the normal force as a function of average bone strength and screw shear area by multiplying by the cosine of the angle between the normal force and hypotenuse using the below formula:

Fig. 2.

The angle, θ (degrees), was measured between the fracture plane of the scaphoid and the long axis of the screw. The angle between the compressive force and the hypotenuse, α, was found by subtracting θ from 90 degrees. The angle α was used to calculate the normal force (compressive force).

Compressive force = shear strength × screw shear area × Cos (α)

Statistical Analysis

Wilcoxon signed-rank tests and Pearson correlations were used to compare compressive forces. Ratios of compressive forces in PERP and PTP groups were compared for descriptive statistics. The level of statistical significance was defined with an α level of p < 0.05.

Results

The angle between screw and fracture in the PTP group ranged from 36 to 84 degrees (mean, 58 ± 16 degrees). By definition, the PERP screw angle was 90 degrees. Fracture orientation included five transverse, two horizontal oblique, two coronal, and one vertical oblique fracture. Screw engagement length was significantly greater in the PTP group (mean, 24 ± 4 mm; range, 18–30 mm) than in the PERP group (mean, 20 ± 3 mm; range, 16–26 mm; p < 0.05) ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Fracture type, angle of screw, screw length, and compression strength of PTP and PERP screws for each scaphoid fracture.

| Patient | Fracture type | Angle of screw (deg) | Screw length (mm) | Compression strength (N) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTP | PERP | PTP | PERP | PTP | PERP | ||

| 1 | Vertical oblique | 70.5 | 90.0 | 24 | 18 | 102 | 114 |

| 2 | Transverse | 60.4 | 90.0 | 22 | 18 | 112 | 107 |

| 3 | Transverse | 42.7 | 90.0 | 30 | 22 | 119 | 146 |

| 4 | Horizontal oblique | 54.4 | 90.0 | 28 | 22 | 148 | 146 |

| 5 | Horizontal oblique | 36.0 | 90.0 | 20 | 16 | 55 | 89 |

| 6 | Coronal | 58.7 | 90.0 | 20 | 16 | 33 | 69 |

| 7 | Transverse | 83.0 | 90.0 | 24 | 26 | 176 | 179 |

| 8 | Coronal | 46.7 | 90.0 | 18 | 20 | 35 | 90 |

| 9 | Transverse | 83.6 | 90.0 | 24 | 24 | 161 | 160 |

| 10 | Transverse | 40.9 | 90.0 | 26 | 22 | 32 | 89 |

Abbreviations: PERP, perpendicular; PTP, pole-to-pole.

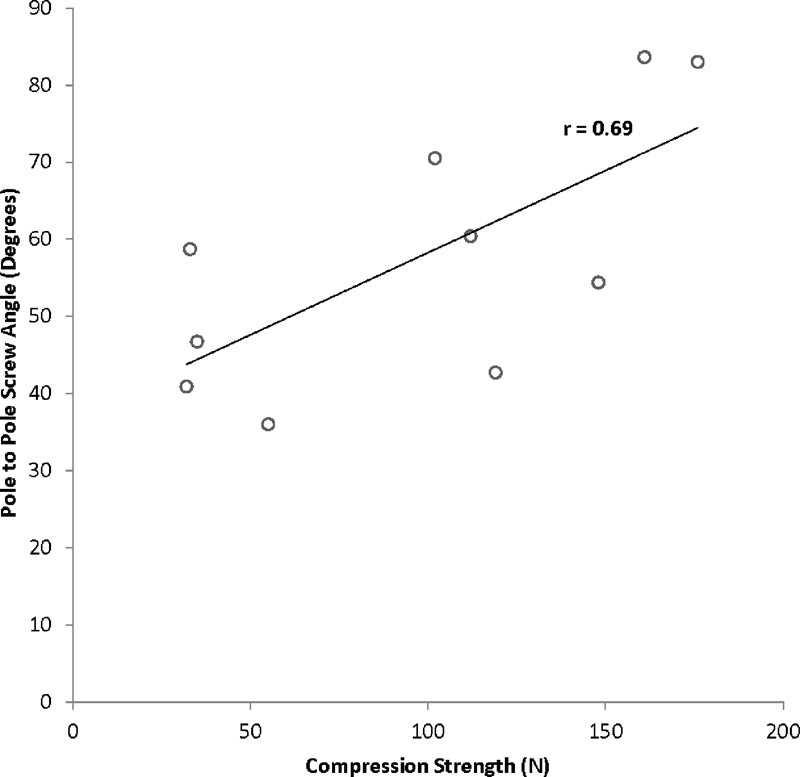

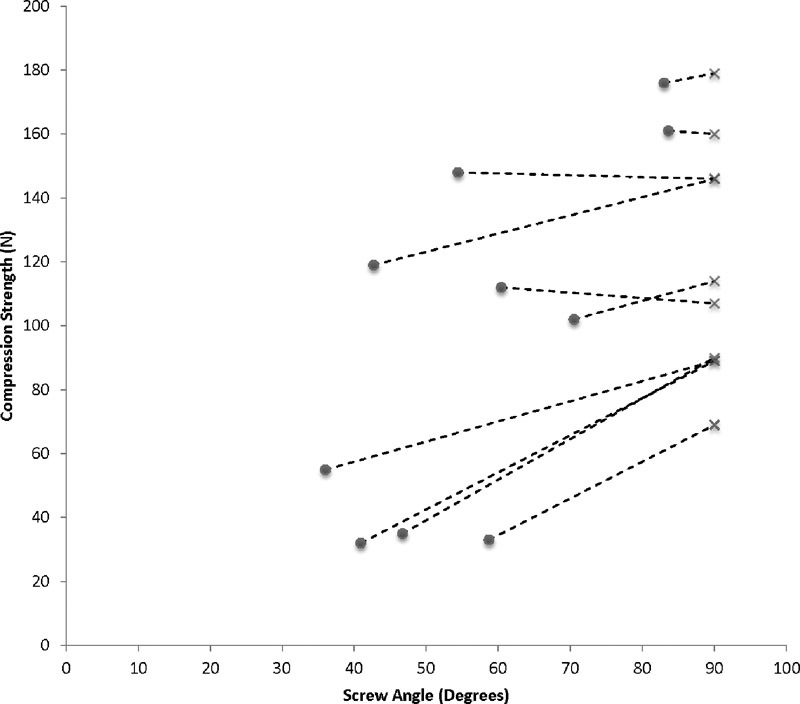

There was a significant positive correlation between perpendicularity of the PTP screw to the fracture and its compression strength ( r = 0.69, p < 0.05) ( Fig. 3 ). PERP screws had significantly more compression than PTP screws when the PTP screw to fracture angle was < 80 degrees (106 vs. 80 N, p < 0.05). When the PTP screw to fracture angle was > 80 degrees, the PTP screw approximated the PERP screw, and there was no difference in compression between PTP (169 N) and PERP (170 N) screw placements ( p > 0.05) ( Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 3.

Correlation between pole-to-pole screw angle and screw compression strength. Increasing perpendicularity of the pole-to-pole screw increased compression.

Fig. 4.

Compression strength at differing screw angles in scaphoid waist fractures. • indicates pole-to-pole screw; × indicates perpendicular screw. For the same fracture, the perpendicular screw marked with a × had superior compression.

Numbers of fracture type were not large enough to perform subgroup analyses, but there was a trend toward the most improvement in compression with PERP fixation in coronal fracture types compared with differences in compression with PERP fixation in other fracture types ( Table 2 ).

Table 2. Subgroup compression ratios for PERP and PTP screws for each scaphoid fracture.

| Patient | Fracture type | Compression PERP/PTP |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vertical oblique | 1.12 |

| 2 | Transverse | 0.96 |

| 3 | Transverse | 1.22 |

| 4 | Horizontal oblique | 0.99 |

| 5 | Horizontal oblique | 1.60 |

| 6 | Coronal | 2.08 |

| 7 | Transverse | 1.02 |

| 8 | Coronal | 2.55 |

| 9 | Transverse | 1.00 |

| 10 | Transverse | 2.79 |

Abbreviations: PERP, perpendicular; PTP, pole-to-pole.

Discussion

Nonunion is a frequent concern when treating scaphoid fractures (5–25%). 22 Anatomic reduction and stabilization by scaphoid compression screw fixation can improve chances of union. Our study finds that increasing screw perpendicularity in scaphoid waist fractures results in higher compressive forces across the fracture site, thus improving fixation. The increased compression gained from PERP screw placement offsets the decreased engagement length. The only time the PTP screw equals the compression of a PERP screw is when it is actually PERP to the fracture.

Our study confirms prior work by Luria et al in 2010. 4 Using a computer modeled finite element analysis, they showed, via mesh algorithms, improved stability (by measuring movement at the modeled fracture site) with PERP fixation in oblique, transverse waist, and proximal fracture patterns. They were unable to reproduce this in their cadaver study in 2012, which showed no difference in stiffness and load to failure between central and PERP screws in oblique scaphoid fractures. 5 Faucher et al in 2014 also performed a cadaveric analysis of fixation strength in oblique scaphoid fractures and found equivalent strength in cyclic loading and load to failure between PTP and PERP screws. 6 We agree, however, with rationale that computer-based models allow for a more precise comparison. 5 Advantages of a computer model include the ability to control for variability in screw placement and to precisely analyze screw angles. The equation we utilized for compression determination allows calculation of the amount of bone in the screw threads and determines the shear strength of the bone, variables which have been defined as primary variables in compression. 21 Computer models also eliminate the variability in specimens and variability in the mechanical testing environment.

We chose to analyze scaphoid waist fractures in this study. Scaphoid waist fractures are the most common type of scaphoid fracture and exhibit a variety of fracture configurations (transverse, horizontal oblique, vertical oblique, and coronal). 23 24 25 26 An advantage of our study compared with prior studies is that our cohort includes many different scaphoid morphologies with real and varied fracture patterns, which imparts generalizability of our results. Our correlation results are independent of fracture orientation. In addition, scaphoid waist fracture fixation requires rigid stability to counteract the bending, rotational, and translational forces present in this region as shown in biomechanical studies. 9 27 28 29 Therefore, knowledge of the best fixation strategies in this group is most important.

Others have studied “peripheral,” screw placement. 1 3 6 30 Trumble et al in 1996 performed a retrospective clinical evaluation of scaphoid union. 3 They found that cannulated screws placed in the central one-third of the scaphoid were associated with improved time to union as compared with eccentric screws. In their 2000 clinical report, numbers of eccentric screws were too small to evaluate for a difference. 30 This was further studied in the biomechanical study by McCallister et al in 2003 which demonstrated that, in cannulated screw fixation of transverse scaphoid fractures, central screws produced significantly greater stiffness, load at 2 mm of displacement and load at failure than eccentric screws. 1 In these reports, central screws were better than noncentral screws but were not compared with PERP screws. In other cases, eccentric screw positioning was PERP and this PERP fixation was superior to central in this computational model of surface area available. 7 Non-PERP, eccentric screws do not impart the biomechanical advantage of improving compression through decreasing shear area that is obtained with PERP eccentric screws.

Our study has limitations inherent to computer-modeled studies. It is a simulated evaluation and not based on clinical outcomes or in vivo biomechanical factors. In addition, our analysis relies on fracture planes rather than irregular fracture pattern. We were also limited on fracture patterns based on our cohort. The Acutrak 2 Mini screw is also a tapered variable pitch screw and the formula used assumes that the bone in the threads fail all at once, which would not happen in vivo. This would not affect the results of our study, however, as we compare such as variables to reach our conclusion and despite this, the compressive forces calculated in this study are comparable to those found in other cadaveric studies. 16 Another limitation of the study is that we assumed constant density of the scaphoid for all specimens. It is possible that with the screws in varying orientations, the average density along the length of engagement may differ. Despite these limitations, this novel computer-modeled study provides valuable information regarding the orientation of screws in scaphoid fractures and can provide a foundation for future studies.

Based on the results of our study in scaphoid waist fractures, we recommend placing screws PERP to the fracture plane to achieve greatest compression. In transverse waist fractures, PTP screws are likely to also be perpendicular screws. In oblique waist fractures, screw perpendicularity increases compression across the fracture site despite a shorter screw.

Conflict of Interest None.

Note

Institutional Ethical Board Review approval was obtained from Hospital for Special Surgery's IRB. Work was performed at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York.

References

- 1.McCallister W V, Knight J, Kaliappan R, Trumble T E.Central placement of the screw in simulated fractures of the scaphoid waist: a biomechanical study J Bone Joint Surg Am 200385-A0172–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dodds S D, Panjabi M M, Slade J F., III Screw fixation of scaphoid fractures: a biomechanical assessment of screw length and screw augmentation. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(03):405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trumble T E, Clarke T, Kreder H J. Non-union of the scaphoid. Treatment with cannulated screws compared with treatment with Herbert screws. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(12):1829–1837. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199612000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luria S, Hoch S, Liebergall M, Mosheiff R, Peleg E. Optimal fixation of acute scaphoid fractures: finite element analysis. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35(08):1246–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luria S, Lenart L, Lenart B, Peleg E, Kastelec M. Optimal fixation of oblique scaphoid fractures: a cadaver model. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(07):1400–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faucher G K, Golden M L, III, Sweeney K R, Hutton W C, Jarrett C D. Comparison of screw trajectory on stability of oblique scaphoid fractures: a mechanical study. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(03):430–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hart A, Harvey E J, Lefebvre L P, Barthelat F, Rabiei R, Martineau P A. Insertion profiles of 4 headless compression screws. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(09):1728–1734. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fowler J R, Ilyas A M.Headless compression screw fixation of scaphoid fractures Hand Clin 20102603351–361., vi [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gruszka D S, Burkhart K J, Nowak T E, Achenbach T, Rommens P M, Müller L P. The durability of the intrascaphoid compression of headless compression screws: in vitro study. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(06):1142–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Assari S, Darvish K, Ilyas A M. Biomechanical analysis of second-generation headless compression screws. Injury. 2012;43(07):1159–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crawford L A, Powell E S, Trail I A. The fixation strength of scaphoid bone screws: an in vitro investigation using polyurethane foam. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(02):255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugathan H K, Kilpatrick M, Joyce T J, Harrison J W. A biomechanical study on variation of compressive force along the Acutrak 2 screw. Injury. 2012;43(02):205–208. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grewal R, Assini J, Sauder D, Ferreira L, Johnson J, Faber K. A comparison of two headless compression screws for operative treatment of scaphoid fractures. J Orthop Surg. 2011;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pensy R A, Richards A M, Belkoff S M, Mentzer K, Andrew Eglseder W. Biomechanical comparison of two headless compression screws for scaphoid fixation. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2009;18(04):182–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hausmann J T, Mayr W, Unger E, Benesch T, Vécsei V, Gäbler C. Interfragmentary compression forces of scaphoid screws in a sawbone cylinder model. Injury. 2007;38(07):763–768. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beadel G P, Ferreira L, Johnson J A, King G JW. Interfragmentary compression across a simulated scaphoid fracture--analysis of 3 screws. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29(02):273–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newport M L, Williams C D, Bradley W D. Mechanical strength of scaphoid fixation. J Hand Surg [Br] 1996;21(01):99–102. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(96)80021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw J A. Biomechanical comparison of cannulated small bone screws: a brief follow-up study. J Hand Surg Am. 1991;16(06):998–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(10)80058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tencer A F, Asnis S E, Harrington R M, Chapman J R. New York: Springer; 1996. Biomechanics of cannulated and noncannulated screws; pp. 15–40. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crookshank M, Ploeg H L, Ellis R, MacIntyre N J. Repeatable calibration of hounsfield units to mineral density and effect of scanning medium. Advances in Biomechanics and Applications. 2014;1(01):15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter D R, Hayes W C.Bone compressive strength: the influence of density and strain rate Science 1976194(4270):1174–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haisman J M, Rohde R S, Weiland A J; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.Acute fractures of the scaphoid J Bone Joint Surg Am 200688122750–2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin A Y, Horton T, Bishop A T. Acute coronal plane scaphoid fracture and scapholunate dissociation from an axial load: a case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30(02):366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ng K CK, Leung Y F, Lee Y L. Coronal fracture of the scaphoid--a case report and literature review. Hand Surg. 2014;19(03):423–425. doi: 10.1142/S0218810414720290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russe O. Fracture of the carpal navicular. Diagnosis, non-operative treatment, and operative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1960;42-A:759–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozin S H. Incidence, mechanism, and natural history of scaphoid fractures. Hand Clin. 2001;17(04):515–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobayashi M, Garcia-Elias M, Nagy L et al. Axial loading induces rotation of the proximal carpal row bones around unique screw-displacement axes. J Biomech. 1997;30(11/12):1165–1167. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)00080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia-Elias M. Kinetic analysis of carpal stability during grip. Hand Clin. 1997;13(01):151–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith D K, Cooney W P, III, An K N, Linscheid R L, Chao E Y.The effects of simulated unstable scaphoid fractures on carpal motion J Hand Surg Am 198914(2 Pt 1):283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trumble T E, Gilbert M, Murray L W, Smith J, Rafijah G, McCallister W V. Displaced scaphoid fractures treated with open reduction and internal fixation with a cannulated screw. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(05):633–641. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200005000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]