Abstract

Disparities exist between Latinos and non-Latino whites in cognitive function. Dance is culturally appropriate and challenges individuals physically and cognitively, yet the impact of regular dancing on cognitive function in older Latinos has not been examined. A two-group pilot trial was employed among inactive, older Latinos. Participants (N = 57) participated in the BAILAMOS© dance program or a health education program. Cognitive test scores were converted to z-scores and measures of global cognition and specific domains (executive function, episodic memory, working memory) were derived. Results revealed a group × time interaction for episodic memory (p<0.05), such that the dance group showed greater improvement in episodic memory than the health education group. A main effect for time for global cognition (p<0.05) was also demonstrated, with participants in both groups improving. Structured Latin dance programs can positively influence episodic memory; and participation in structured programs may improve overall cognition among older Latinos.

Introduction

By 2050, it is expected that 20% of the older population in the U.S. will be comprised of Latinos (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, July 2010). Disparities exist between Latinos and non-Latino whites in cognitive function, as Latinos have twice the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) compared to non-Latino whites (Tang et al., 2001). This is significant because the number of Latinos in the U.S. with AD is projected to increase by an astonishing 600% in the next 50 years (Novak & Riggs, 2010). Individuals with low socioeconomic status (SES) also have twice the risk of developing AD (Stern et al., 1994). A considerable proportion of older Latinos in the U.S. have low SES, and are thus at increased risk for AD.

Many health benefits associated with physical activity (PA) in the older adult population have been documented (Chodzko-Zajko et al., 2009). However, evidence indicates that racial/ethnic disparities in PA exist. Specifically, Latinos aged 55–74 are 46–50% less likely to engage in leisure time PA (LTPA) than older non-Latino whites of comparable age (Marquez, Neighbors, & Bustamante, 2010). Also, older Latinos are largely uninformed about the impact of PA on brain health (Wilcox et al., 2009), and thus appear to be a population in need of intervention.

Dancing and walking have been cited as the only age-appropriate PA for older Latina women (Cromwell & Berg, 2006). However, unsafe neighborhoods and unfavorable weather conditions are significant barriers to walking for many older adults (Belza et al., 2004). Dance has long been an important form of socialization and leisure in Latin cultures (Delgado & Munoz, 1997), and dance challenges individuals both physically and cognitively. Thus, dance may provide additional cognitive benefits relative to other forms of PA such as walking. Latin dance also offers a unique dimension not found in traditional aerobic exercise, namely, it is a complex sensorimotor rhythmic activity integrating multiple physical, cognitive and social elements (Merom et al., 2013). Dance holds considerable promise as a culturally appropriate form of PA. In addition, it requires individuals to plan, monitor, and execute a sequence of goal-directed complex actions, potentially influencing cognitive function.

In a recent review of the influence of exercise programs on cognition, Gregory and colleagues found that dual-task training, multidimensional type of intervention that combines simultaneous cognitive and motor tasks, holds promise for influencing cognition (Gregory, Gill, & Petrella, 2013). Although dance programs do not intentionally target cognitive and motor tasks, they are inevitably included in dancing. Moreover, Forte and colleagues examined the effect of multicomponent training versus progressive resistance training on executive cognitive functions in a small sample of community dwelling older adults. They found that cognitive measures of inhibition improved independent of training type; however, multicomponent training directly affected inhibition, whereas resistance training indirectly influenced inhibition via gains in muscular strength, suggesting that different types of training might lead to benefits through different pathways (Forte et al., 2013). It is possible that similar findings would result from dancing, a potential form of multicomponent training.

Preliminary dance research indicates that it is associated with cognitive improvements (Kattenstroth, Kalisch, Holt, Tegenthoff, & Dinse, 2013) and can improve older adults’ lower extremity function (Keogh, Kilding, Pidgeon, Ashley, & Gillis, 2009). To our knowledge, no dance intervention studies have been conducted with older Latinos, a rapidly growing segment of the population with known low levels of LTPA (Marquez et al., 2010) and high levels of cognitive decline (Novak & Riggs, 2010). As a result, we developed the BAILAMOS© (Balance and Activity In Latinos, Addressing Mobility in Older Adults) dance program, a culturally-appropriate Latin dance program for this under-served population (Marquez, Bustamante, Aguinaga, & Hernandez, 2014). A single group, pre-post 3-month pilot of BAILAMOS© demonstrated substantial program feasibility and effect sizes (Cohen’s d) indicated very small improvements in cognitive function (ds=.11–.12) (Marquez et al., 2014). Feedback from participants led to a revised 4-month program. The objective of the current pilot intervention was to test the impact of the revised BAILAMOS© program on cognitive function at 4 months in low-active older Latinos compared to a health education control group. It was hypothesized that participants in the BAILAMOS© intervention group would demonstrate greater improvement in aspects of cognitive function at 4 months compared to the control group.

Methods

Overview and Study Design

Study approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at the University of XXX, XXX University, and University of XXX. A two-group pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) with randomization at the level of the individual was used. One community senior center hosted the intervention, two waves of the intervention were conducted, and participants in each wave were randomized.

Participants & Recruitment

Inclusion criteria (self-reported) were: (1) aged ≥ 55 years; (2) self-identification as Latino/Hispanic; (3) ability to understand Spanish; (4) participation in ≤2 days/week of aerobic exercise; (5) at risk for disability (see below); (6) adequate cognitive status as assessed by a version of the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975), modified for telephone administration, and validated in the Rush Memory and Aging Project (Bennett et al., 2005); (7) danced < 2 times/month over the past 12 months; (8) willingness to be randomly assigned to treatment or control group; (9) no current plans to leave the country for more than two consecutive weeks over the next year.

Exclusion criteria (self-reported) included: (1) presence of heart disease or uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, (2) pacemaker in situ, (3) stroke, (4) severe chronic lung disease (emphysema or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), (5) recent healing or unhealed fracture(s) in the last 6 months, (6) heart failure, (7) major head injury, (8) chronic kidney disease, (9) frequent falls in the past 12 months, and (10) require help to walk (cane, walker, or wheelchair) as these individuals are already considered mobility disabled (Simonsick et al., 2008; Weiss, Fried, & Bandeen-Roche, 2007).

At risk for disability was operationally defined as one of the following: (1) Presence of diabetes (Al Snih et al., 2007); (2) Underweight (BMI lower than 18.5) (Al Snih et al., 2007); (3) Overweight or obese (BMI greater than 25.0) (Al Snih et al., 2007; Chen, Bermudez, & Tucker, 2002); or (4) Difficulty or change with any one of the following four tasks: (a) walking a long distance (4 blocks or ½ mile), (b) climbing 10 steps, (c) transferring from a bed or chair, (d) walking a short distance on a flat surface. Two questions were asked for each task: “Have you had difficulty (task)” and “Have you changed the way you (task) or how often you do this, due to a health or physical condition?” Older adults with difficulty or change with any one of the four tasks will be eligible for the study, similar to methods used by Weiss et al. (Weiss et al., 2007) and those used in our BAILAMOS© pilot study.

We used the Exercise Assessment and Screening for You (EASY) questionnaire to detect conditions that could preclude exercise participation (Resnick et al., 2008). The EASY has recommendations for when physician evaluation is needed before beginning a PA program (e.g., when the individual reports new-onset shortness of breath, pain, or dizziness that has not been previously evaluated by a health care provider).

Participants were recruited using established relationships of the lead author. Recruitment was primarily done through presentations at the study site, which has a large Latino population; and through local Roman Catholic Churches. Additionally, participants were recruited through health centers and clinics, word of mouth, flyers in senior housing facilities, and senior fairs and health fairs.

Measures

Descriptive variables

Demographics

Information about age, sex, education, income, marital status, country of origin, race, ethnicity, preferred language, years lived in the U.S., and number of children was assessed.

Physical health

Weight was measured using the Tronix 5002 Stand-On Scale or Seca 803 Flat Scale. Height was measured using the Seca 216 Mechanical Stadiometer or Seca 213 Portable Stadiometer. Body mass index (BMI)(kg/m2) was used to provide a measure of overall size. Blood pressure was assessed while seated at rest with the Welch-Allyn Spot Vital Signs® LXI Device or Omron HEM-907XL Digital Blood pressure monitor.

Acculturation

The Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II (ARSMA-II)(Cuellar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995) is a 30-item scale that measures acculturation along 3 primary factors: language, ethnic identity, and ethnic interaction. We revised the wording of items to be more inclusive of all Latino subgroups (e.g., Puerto Ricans, Dominicans). ARSMA-II generates both linear acculturation categories (Levels 1–5) and orthogonal acculturative categories (Traditional, Low Biculturals, High Biculturals, Assimilated). This measure has adequate validity and reliability (Cuellar et al., 1995).

Cognitive Function

We used a subsample of tests from the official Spanish version of measures in the Uniform Data Set (UDS) of the National Institute on Aging Alzheimer’s Disease Center Program (Acevedo et al., 2009). The tests used assess functions that decrease with age and also are influenced by regular PA (i.e., executive function, working memory, perceptual speed, episodic memory).

Executive Function

The Trail Making Test (TMT; Parts A & B) (Adjutant General’s Office, 1944) has two parts. It requires an individual to draw lines sequentially connecting 25 encircled numbers randomly distributed on a page (Part A) and encircled numbers and letters in alternating order (Part B). The score was the time required to complete each task.

The Color task (Stroop C) of the short form (Wilson et al., 2005) of the Stroop Neuropsychological Screening Test (Trenerry, Crosson, DeBoe, & Leber, 1989) shows participants the names of colors printed in conflicting ink colors and asks them to name the words. The second task is the Color–Word task (Stroop C-W) in which the participant is shown the names of colors printed in conflicting ink colors (e.g., the word “blue” in red ink) and is asked to name the color of the ink rather than the word. The scores were the number of words named correctly in 30 seconds minus the number of errors; and the number of colors named correctly in 30 seconds minus the number of errors (Wilson et al., 2005).

The Word fluency test (Welsh et al., 1994) asks participants to generate as many examples as possible from two semantic categories (animals; fruits and vegetables) in separate 60-second trials. A word fluency score was created by summing the number of animals generated with the number of fruits and vegetables generated.

For the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (Smith, 1982) the participant was asked to identify and name the digits which belonged with consecutively presented symbols. The score was the number of digits correctly paired with symbols in 90 seconds.

Working Memory

The Digit Span test (Wechsler, 1987) includes two parts. Digit strings of increasing length were read and the participant was asked to repeat each string forward (Digit Span Forward) or backward (Digit Span Backward). The score was the number of correctly retrieved strings in each part (Wechsler, 1987).

For the Digit Ordering test (Cooper, Sagar, Jordan, Harvey, & Sullivan, 1991; Wilson et al., 2005) digit strings of increasing length were read and the participant was asked to reorder the digits and say them in ascending order. The score was the number of correctly reordered strings (Wilson et al., 2005).

Episodic Memory

Logical Memory I (Immediate) and II (Delayed) (Wechsler, 1987) has two parts. A brief story was read to the participant who was then asked to retell it immediately (I) and after a 10-minute delay filled with other activities (II). The score was the number of the 25 story units recalled immediately (I) and after the delay (II).

Procedures

Randomization, Testing, and Enrollment

Potential participants consented to be screened in several ways, including learning about the study and signing a sheet agreeing to be called by a research member at a later time; and learning about the study another way and calling our office to be screened. Bilingual staff screened all interested individuals for eligibility based on inclusion and exclusion criteria.

After participants were considered eligible they were scheduled for baseline testing. Testing lasted 1–2 hours. Data collection research staff were not informed as to which study condition participants were enrolled in. Wave 1 had their testing conducted at the study site, whereas Wave 2 had their testing conducted at the UIC Clinical Research Center (CRC) of the Center for Clinical and Translational Science, due to additional available funding. Participants in Wave 2 were offered complementary rides from a taxi service to and from the UIC CRC (using an established contract of the lead author with the taxi service). For those participants who refused to come to the university for post-intervention testing, we offered to conduct testing at the study site (i.e., the senior center).

At the baseline testing session a staff member explained the study and read the Informed Consent to the participant which the participant then signed. Questionnaires and tests (available in Spanish or English) were then administered. Participants were compensated with $10 for their participation. At 4-months, post-intervention testing transpired, and participants were paid $10 as compensation.

Older Latinos who qualified for the study and completed baseline testing were randomly assigned to the dance treatment or to the health education control group using randomization in the Study360™ software (Almedtrac, Inc.). Randomization was stratified based on sex, as it was likely that fewer men than women would participate and randomization in this way would help to ensure that approximately the same number of men were in each study condition.

Dance program

Basics of the dance aspects of BAILAMOS© have previously been reported (Marquez et al., 2014). Based partially upon participant feedback, BAILAMOS© was revised to be 16 weeks in duration with open dance sessions. In brief, BAILAMOS© is a 4-month, twice-weekly dance program that has four dance styles (Merengue, Cha Cha Cha, Bachata, and Salsa) which are ordered by level of difficulty. Each dance class was one hour in duration and of light-moderate intensity. The PI and a bilingual professional dance instructor co-developed the extensive BAILAMOS© Dance Manual for instructors and a detailed class-by-class schedule. Each session includes a warm-up and stretching, followed by instructions of the basics of the respective styles of dance, followed by advanced steps for singles and couples dancing. For couples, dancing participants learn the roles of both leaders and followers, and continually rotate partners. Each session ends with a 5 minute cool-down. Bimonthly “Fiestas de Baile,” “Dance Parties” are included in which the instructor is present and participants spend time dancing and practicing what they have learned. These sessions are part of the program, not additional classes.

Health Education program

Health educators from the University of XXX Extension taught classes in Spanish using Spanish-language materials. The curriculum covered the following topics: stress, home safety, fats and carbohydrates, My Pyramid, food labels, diabetes, cancer, osteoporosis, immunizations, self-esteem, healthy relationships, building a better memory, and making the most of medical appointments. Classes met one day per week for two hours, to provide social contact equivalent to that in the dance group.

Statistical Analysis

A two-way ANOVA with 2 factors (dance intervention and control group) and 2 measurements (pre-post) was used to examine differences between groups on the cognitive measures over time. Post-hoc analyses were not performed given we only had two treatments and time points. These analyses were conducted using the GLM procedure in IBM SPSS version 22 software. The results were recorded at a level of significance of 0.05 and the outcome difference between different treatments were indicated by effect sizes using Cohen’s d (difference from baseline to follow-up divided by the pooled standard deviation) (Cohen, 1988).

To assess the changes in cognitive performance tests, we combined the tests into composite scores (executive function, episodic memory, working memory, and global cognition) by averaging the z scores converted from each test (Wilson et al., 2002). Those z scores were computed by using the population mean and SD from the baseline measurements.

Missing Data

Sequential hot decking (Rubin, 1989) is a useful technique for imputing missing data when there is mostly complete baseline data and some incomplete post-intervention data, as is the case with this study. The baseline data is a simple and intuitive choice for creating the donor class (observations not missing data) (Fricker, 2013), since it can be safely assumed that the baseline data will be correlated with the post-intervention data for each measure.

Hot decking is simpler to perform and makes fewer parametric assumptions about the data than multiple imputation. Because it resamples the empirical dataset, rather than fitting it to a normal distribution, it better retains the shape of non-normal distributions. One disadvantage of hot decking is that while it retains the same mean and variance as the original data, it can change the variance/covariance more than multiple imputation (Groenwold, Donders, Roes, Harrell, & Moons, 2012).

Therefore, the dataset was sorted by the baseline measure and the corresponding post-intervention measures were imputed. If both time points were missing, the participant’s data was deleted from the analysis, resulting in the dataset used in the current analysis.

Results

Descriptives

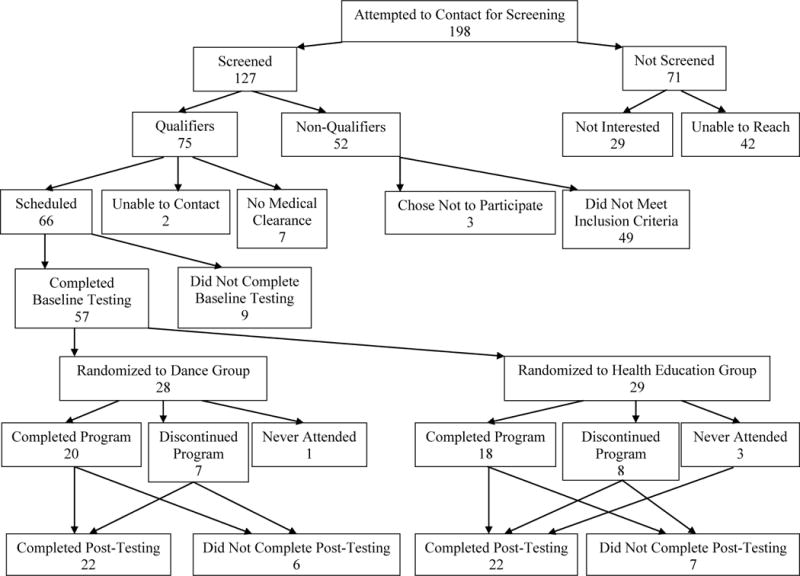

The flow of participants is shown in the CONSORT figure, Figure 1. As can be seen in Table 1, there were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between the Dance and Health Education groups at baseline. Overall the participants (age range 55–80) were mostly female, obese, non-smokers, U.S. residents for about half of their lives, former residents of Mexico, and had low levels of education and income. On average, participants in the dance program attended 66% of 32 classes offered, and participants in the health education program attended 62% of 16 classes offered.

Figure 1.

CONSORT FLOWCHART

Table 1.

Descriptive information of participants

| Dance Group M(SD)/% (n = 28) |

Health Ed Group M(SD)/% (n = 28) |

p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, % | 14.3% | 17.9% | 1.000 |

| Marital Status | 57.1% Married |

64.3% Married |

0.855 |

| Age | 64.8 ± 6.0 | 66.4 ± 7.0 | 0.373 |

| Weight | 157.9 ± 31.6 | 160.9 ± 37.1 | 0.749 |

| Height (n) | 53.1 ± 15.9 (25) | 55.3 ± 15.7 (27) | 0.622 |

| Number of Children | 4.0 ± 2.0 | 4.8 ± 2.5 | 0.161 |

| Sleep Hours | 64.3% Less than 7 hours |

42.9% Less than 7 hours |

0.259 |

| Occupation in hours/week (n) | 9.0 ± 10.4 (6) | 14.9 ± 20.0 (10) | 0.516 |

| Car driving, % | 50.0 % | 42.9 % | 0.592 |

| Smoking | 0.0 % | 7.1 % | 0.491 |

| Origin Country | 78.6 % Mexico |

75.8 % Mexico |

0.670 |

| Years Lived in the US (n) | 33.2 ± 19.1 (26) | 33.0 ± 18.6 (28) | 0.970 |

| Age of Immigration (n) | 35.6 ± 14 (22) | 32.8 ± 14.7 (27) | 0.498 |

| Spanish Preferred, % | 96.4 % | 81.5 % | 0.101 |

| Ethnicity | 100% Latino |

100% Latino |

1.000 |

| Years of Education | 7.4 ± 4.0 | 6.4 ± 4.0 | 0.369 |

| Income | 78.6% Low |

67.9% Low |

0.343 |

| Body Mass Index at Baseline | 30.1 ± 5.4 | 31.6 ± 6.6 | 0.385 |

| Acculturation Score | −1.89 ± 1.06 | −2.07 ± 0.97 | 0.538 |

Note: Acculturation scores range from −5 to +5, and Level 1 represents a Very Latino Orientation (mean < −1.33), whereas Level 5 represents Very Assimilated or Anglicized Individual (mean > 2.45).

Pre-Post Intervention Outcomes

Table 2 shows pre-post intervention changes in cognitive function. Based on the repeated-measures analysis of variance, a significant group × time interaction was demonstrated for episodic memory (F (1, 55) =5.78, p<0.05), and more specifically for logical memory delayed (F (1, 55) =6.01, p<0.05), with the dance group showing significantly greater improvement than the health education group. Results also revealed a main effect for time for global cognition (F (1, 54) =4.15, p<0.05), with participants in both groups demonstrating improvement. A main effect for group was found such that the dance group performed significantly better in executive function (F (1, 55) =5.18, p<0.05).

Table 2.

Relation of intervention group, time, and their interaction to global and specific measures of cognitive function*

| Measure | Pre-intervention M(SD) |

Post-intervention M(SD) |

Effect size | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Time | |||||

| Interaction | ||||||

| Global cognition | ||||||

| Dance | −0.01(0.39) | 0.10(0.39) | 0.22 | 0.564 | 0.047** | |

| Health Ed | −0.03(0.45) | −0.01(0.46) | 0.141 | |||

| Executive Function | ||||||

| Dance | 0.11(0.33) | 0.08(0.35) | 0.00 | 0.027** | 0.416 | |

| Health Ed | −0.08(0.32) | −0.11(0.37) | 0.998 | |||

| Working Memory | ||||||

| Dance | −0.06(0.74) | −0.04(0.59) | 0.12 | 0.635 | 0.692 | |

| Health Ed | 0.08(0.86) | 0.01(0.76) | 0.516 | |||

| Episodic Memory | ||||||

| Dance | −0.28(0.77) | 0.27(0.91) | 0.49 | 0.948 | 0.001 | |

| Health Ed | −0.04(0.99) | 0.05(1.05) | 0.02** | |||

| Logical Memory | ||||||

| Test I | Dance | 8.93(3.33) | 10.68(3.70) | 0.33 | 0.716 | 0.005** |

| Health Ed | 9.93(4.23) | 10.38(4.22) | 0.090 | |||

| Test II | Dance | 7.36(2.95) | 9.86(3.75) | 0.60 | 0.797 | 0.003 |

| Health Ed | 8.24(3.61) | 8.52(4.47) | 0.017** | |||

Estimated from 5 repeated measures ANOVA

p< .05

Global cognition: composite score of all cognitive tests; Executive Function: Trail Making Test (Parts A & B), Color task (Stroop C) and Color–Word task (Stroop C-W), Word fluency test, Symbol Digit Modalities Test; Working Memory: Digit Span test, Digit Ordering test; Episodic Memory: Logical Memory I (Immediate) and II (Delayed)

Discussion

Despite the calls for more PA among older adults, including dancing, few studies have examined the health effects of dancing in this group. In Italy, Mangeri and colleagues had middle- and older-aged adults with diabetes and/or obesity enroll in either a dance program or in a self-selected PA program. Both programs significantly decreased body composition at 3 months and 6 months (Mangeri, Montesi, Forlani, Grave, & Marchesini, 2014), but participants were not randomized into study conditions, and cognition was not assessed. Recent evidence suggests that Latin partnered social dance to salsa music is of moderate to vigorous PA intensity, and promotes interest, enjoyment, and a positive psychological outlook among novice to advanced adult Latin dancers (Domene, Moir, Pummell, & Easton, 2014). To our knowledge, however, no studies examining the impact of a dance intervention on the cognition of Latinos have been conducted to date.

In the current study significant changes in episodic memory were demonstrated. Participants in the dance condition remembered significantly more items on the Logical Memory Delayed test at 4 months relative to those in the health education condition; and there was a nearly significant interaction in the same direction on the Logical Memory Immediate test at 4 months. These results have potential public health significance because of the importance of episodic memory to late-life cognition. Accelerated decline of episodic memory is a defining feature of dementia (McKhann et al., 1984) in old age. Clinical-pathologic research has shown that diverse dementia-related neurodegenerative and cerebrovascular pathologies are associated with episodic memory decline (Wilson, Leurgans, Boyle, Schneider, & Bennett, 2010; Wilson et al., 2013). The present results suggest, therefore, that strengthening function in this highly vulnerable memory system might help delay the onset of common debilitating late-life cognitive disorders.

There are several reasons to believe that dancing can lead to changes in cognitive function. It has been reported that three lifestyle factors can play a significant role in slowing the rate of cognitive decline and preventing dementia: a socially integrated network, cognitive leisure activity, and regular PA (Fratiglioni, Paillard-Borg, & Winblad, 2004). It can be argued that dancing is one of the few activities that addresses these three factors with one activity (Behrman & Ebmeier, 2014); it takes place in a social atmosphere with peers, requires active cognitive input when learning dance steps, and involves bodily movement resulting in energy expenditure. Moreover, it is possible that dance routines or other exercise regimens requiring some cognitive input (versus an activity like walking) may confer additional benefit to cognitive function. Kattenstroth et al., 2010 suggested that dancing activities are the equivalent of enriched environmental conditions for humans since they provide an individual with increased sensory, motor, and cognitive demands (Kattenstroth, Kolankowska, Kalisch, & Dinse, 2010).

The current study was able the show the beneficial cognitive effects of regular Latin dance in older Latinos. Participants in the dance condition significantly improved on the composite score of cognition, as did participants in the health education condition, but the interaction was nearly significant. Previous studies, with some distinct differences from the present study, showed similar findings. In Brazil neuropsychological performance on language tests improved in institutionalized and non-institutionalized participants as a result of a stimulation intervention (Galdino De Oliveira et al., 2014). Unfortunately, the intervention included many components in addition to dance, including language and memory exercises, as well as visual, olfactory, auditory, and ludic stimulation (music, singing, and dance); thus it is not possible to tease out the specific benefit of dance on cognition.

In Germany participants attended the Agilando™ dance program developed for older adults. Benefits in cognition were demonstrated without any changes in cardiorespiratory performance. However, the authors collapsed the data by grouping the various selective attention and concentration tests into one functional cognitive domain named “Cognition/Attention” (Kattenstroth et al., 2013). Within the US, studies examining the impact of Tango on cognition have been conducted. McKee and Hackney tested the effects of community-based adapted tango on spatial cognition in individuals with mild-to-moderate Parkinson’s Disease (stage I-III) (McKee & Hackney, 2013). Participants were assigned to twenty 90-min tango (n = 24) or education (n = 9) lessons over 12 weeks. There was a main effect of time on global cognition/executive function; a nearly significant effect of time on visuospatial memory; and there was a group × time interaction on spatial cognition in which those randomized to the Tango group significantly improved relative to the education group. Gains were also maintained 10–12 weeks post-intervention (McKee & Hackney, 2013).

Research to date has reported that the effects of PA/fitness appear to be largest for cognitive tasks that involve executive function (Colcombe & Kramer, 2003). However, there were non-significant results for the executive function domain analysis in the current study. Previous studies using forms of dance other than Latin dance (e.g., jazz dance) with older adults have also not reported changes in executive function (Alpert et al., 2009).

We had hypothesized significant changes in cognition in the dance condition relative to the control condition (health education), as would be expected in a randomized trial. However, there were main effects for time for several tests. There is a tendency for performance on cognitive tests to improve with repeat administration (retest effects or retest learning), and that could help to explain main effects on cognition. Also, one could argue that the changes in cognition in both groups were the result of the passage of time. However, this is unlikely because both groups got an “intervention.” Nonetheless, it is a possible explanation, and future studies with larger trials and different control groups are necessary to address this issue.

There are other viable explanations for changes in cognition in both study groups, specific to the population the participants were sampled from. There were very low levels of formal education in the control group. Control group participants now had the chance to attend weekly health education classes, and the classes may have been cognitively stimulating. In this sample, with very low education and income levels, the findings that both groups improved in aspects of cognition has potentially practically significant importance. There is great need to provide opportunities for advancement for underserved populations such as older, Spanish-speaking Latinos. The dance program provided one such opportunity. It is unknown if the dance program in other populations with higher education and income levels would show similar results.

Another explanation for both groups improving in cognition is that participants might have been making health behavior changes as a result of the health education classes. There could have been changes in variables not measured in this study, such as diet/nutrition. Some participants mentioned that they had never looked at the nutritional information on food labels. Given evidence of a relationship between cognition and nutrition (Ayers & Verghese, 2014), this is a possible explanation. Also, there were social aspects of the health education class. Social interaction among older adults has been found to be related to cognition in older adults (Strout & Howard, 2012). Research on social engagement and cognitive outcomes such as cognitive decline and incident dementia suggest that the frequency of socially interactive activities and perceived connectedness to others are vital (Wilson et al., 2007).

Despite the novel findings from this study, there are several limitations that need to be taken into consideration. The sample size was somewhat small, and this may have limited our ability to detect dance-related improvements in domains other than episodic memory. Also, we did not have an untreated control group, but instead had a control that got some type of intervention (health education). Further, the study was only conducted at one site in CITY, so the findings might not be generalizable to Latinos in various locations. Our study also did not assess the intensity of the dance sessions, as the intensity of the activity could have been a factor affecting cognition. Also, no follow up measures were employed, so we are unclear if any changes were maintained beyond the length of the dance program.

Finally, we had a number of participants who stopped coming to the program for different reasons. The five primary reasons included (in no particular order): 1) work status change (i.e., from not working to working, and having their shift change); 2) caregiving responsibilities (both for spouses and grandchildren); 3) health issues; 4) transportation issues (i.e., cannot afford bus or their fellow participant who used to provide a ride to class can no longer attend) and 5) travelling back to home country. This is one of the first studies to provide an intervention to older, urban, low SES, Spanish-speaking Latinos, who clearly have many barriers to overcome. Future research intervention studies are needed to address these barriers.

Older Latinos are a rapidly growing segment of the US population, yet are still an underserved group in terms of programs and resources. In part as a result of low levels of PA, the physical and cognitive function of older Latinos is poor relative to older non-Latino whites. Engaging in regular physical activity is one method of influencing cognition, however, among older Latinos there are many who do not have a history of engaging in traditional exercise/physical activity, such as jogging or going to a gym to run on treadmill, lift weights, etc. We have shown that engaging older Latinos in programs of interest to them, namely Latin dancing, or health education classes in Spanish, can influence cognitive health. Future studies are needed to examine these issues are on larger basis, and to examine the mechanisms underlying the changes in cognition.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Alzheimer’s Association (NIRGD-11-205469) and by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (P30AG022849) of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Alzheimer’s Association, National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health.

We acknowledge the contributions and assistance of Veronica Aranda, Patricia Boyle, Michelle Griffith, Sarah Janicek, Sonia Lopez, Miguel Mendez, Thomas Jones and the Southwest Regional Senior Center, and thank all participants.

References

- Acevedo A, Krueger KR, Navarro E, Ortiz F, Manly JJ, Padilla-Velez MM, Mungas D. The Spanish translation and adaptation of the Uniform Data Set of the National Institute on Aging Alzheimer’s Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(2):102–109. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318193e376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adjutant General’s Office. Army Individual Test Battery: Manual of Directions and Scoring. Washington, DC: War Department, Adjutant General’s Office; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Al Snih S, Ottenbacher KJ, Markides KS, Kuo YF, Eschbach K, Goodwin JS. The effect of obesity on disability vs mortality in older Americans. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(8):774–780. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.8.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpert PT, Miller SK, Wallmann H, Havey R, Cross C, Chevalia T, Kodandapari K. The effect of modified jazz dance on balance, cognition, and mood in older adults. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2009;21(2):108–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers E, Verghese J. Locomotion, cognition and influences of nutrition in ageing. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2014;73(2):302–308. doi: 10.1017/s0029665113003716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrman S, Ebmeier KP. Can exercise prevent cognitive decline? Practitioner. 2014;258(1767):17–21. 12–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belza B, Walwick J, Shiu-Thornton S, Schwartz S, Taylor M, LoGerfo J. Older adult perspectives on physical activity and exercise: voices from multiple cultures. Prev Chronic Dis. 2004;1(4):A09. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Mendes de Leon C, Bienias JL, Wilson RS. The Rush Memory and Aging Project: study design and baseline characteristics of the study cohort. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(4):163–175. doi: 10.1159/000087446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Bermudez OI, Tucker KL. Waist circumference and weight change are associated with disability among elderly hispanics. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(1):M19–25. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.1.m19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Proctor DN, Fiatarone Singh MA, Minson CT, Nigg CR, Salem GJ, Skinner JS. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2009;41(7):1510–1530. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a0c95c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Colcombe S, Kramer AF. Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults: a meta-analytic study. Psychol Sci. 2003;14(2):125–130. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.t01-1-01430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JA, Sagar HJ, Jordan N, Harvey NS, Sullivan EV. Cognitive impairment in early, untreated Parkinson’s disease and its relationship to motor disability. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 5):2095–2122. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromwell SL, Berg JA. Lifelong physical activity patterns of sedentary Mexican American women. Geriatr Nurs. 2006;27(4):209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans II - a Revision of the Original Arsma Scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17(3):275–304. doi: 10.1177/07399863950173001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado CF, Munoz JE. Everynight Life: Culture and Dance in Latin/o America. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Domene PA, Moir HJ, Pummell E, Easton C. Physiological and perceptual responses to Latin partnered social dance. Human Movement Science. 2014;37:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans 2010: Key Indicators of Well-Being. 2010 Jul; Retrieved from Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forte R, Boreham CA, Leite JC, De Vito G, Brennan L, Gibney ER, Pesce C. Enhancing cognitive functioning in the elderly: multicomponent vs resistance training. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:19–27. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S36514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratiglioni L, Paillard-Borg S, Winblad B. An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(6):343–353. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00767-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker RD. Introduction to Statistical Methods for Biosurveillance. Cambridge University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Galdino De Oliveira TC, Soares FC, Dias De Macedo LDE, Wanderley Picanco Diniz DL, Oliver Bento-Torres NV, Picanco-Diniz CW. Beneficial effects of multisensory and cognitive stimulation on age-related cognitive decline in long-term-care institutions. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2014;9:309–321. doi: 10.2147/cia.s54383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory MA, Gill DP, Petrella RJ. Brain health and exercise in older adults. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2013;12(4):256–271. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e31829a74fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenwold RH, Donders AR, Roes KC, Harrell FE, Jr, Moons KG. Dealing with missing outcome data in randomized trials and observational studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(3):210–217. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattenstroth JC, Kalisch T, Holt S, Tegenthoff M, Dinse HR. Six months of dance intervention enhances postural, sensorimotor, and cognitive performance in elderly without affecting cardio-respiratory functions. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:5. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattenstroth JC, Kolankowska I, Kalisch T, Dinse HR. Superior sensory, motor, and cognitive performance in elderly individuals with multi-year dancing activities. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;2 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keogh JWL, Kilding A, Pidgeon P, Ashley L, Gillis D. Physical benefits of dancing for healthy older adults: A review. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2009;17:479–500. doi: 10.1123/japa.17.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangeri F, Montesi L, Forlani G, Grave RD, Marchesini G. A standard ballroom and Latin dance program to improve fitness and adherence to physical activity in individuals with type 2 diabetes and in obesity. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome. 2014;6 doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-6-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez DX, Bustamante EE, Aguinaga S, Hernandez R. BAILAMOS(c): Development, Pilot Testing, and Future Directions of a Latin Dance Program for Older Latinos. Health Educ Behav. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1090198114543006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez DX, Neighbors CJ, Bustamante EB. Leisure time and occupational physical activity among racial/ethnic minorities. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2010;42(6):1086–1093. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c5ec05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee KE, Hackney ME. The Effects of Adapted Tango on Spatial Cognition and Disease Severity in Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of Motor Behavior. 2013;45(6):519–529. doi: 10.1080/00222895.2013.834288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merom D, Cumming R, Mathieu E, Anstey KJ, Rissel C, Simpson JM, Lord SR. Can social dancing prevent falls in older adults? a protocol of the Dance, Aging, Cognition, Economics (DAnCE) fall prevention randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:477. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak K, Riggs J. Hispanics/Latinos and Alzheimer’s Disease. 2010 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Raji MA, Al Snih S, Ostir GV, Markides KS, Ottenbacher KJ. Cognitive status and future risk of frailty in older Mexican Americans. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2010;65(11):1228–1234. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick B, Ory MG, Hora K, Rogers ME, Page P, Chodzko-Zajko W, Bazzarre TL. The Exercise Assessment and Screening for You (EASY) Tool: Application in the oldest old population. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2008;2:432–440. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Simonsick EM, Newman AB, Visser M, Goodpaster B, Kritchevsky SB, Rubin S, Harris TB. Mobility Limitation in Self-Described Well-Functioning Older Adults: Importance of Endurance Walk Testing. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2008;63(8):841–847. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.8.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test manual-revised. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Stern Y, Gurland B, Tatemichi TK, Tang MX, Wilder D, Mayeux R. Influence of education and occupation on the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Jama. 1994;271(13):1004–1010. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03510370056032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strout KA, Howard EP. The six dimensions of wellness and cognition in aging adults. Journal of holistic nursing : official journal of the American Holistic Nurses’ Association. 2012;30(3):195–204. doi: 10.1177/0898010112440883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang MX, Cross P, Andrews H, Jacobs DM, Small S, Bell K, Mayeux R. Incidence of AD in African-Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and Caucasians in northern Manhattan. Neurology. 2001;56(1):49–56. doi: 10.1212/WNL.56.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenerry M, Crosson B, DeBoe J, Leber W. Stroop Neuropsychological Screening Test manual. Adessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources (PAR); 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. The Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss CO, Fried LP, Bandeen-Roche K. Exploring the hierarchy of mobility performance in high-functioning older women. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2007;62(2):167–173. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.2.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh KA, Butters N, Mohs RC, Beekly D, Edland S, Fillenbaum G, Heyman A. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part V. A normative study of the neuropsychological battery. Neurology. 1994;44(4):609–614. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.4.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox S, Sharkey JR, Mathews AE, Laditka JN, Laditka SB, Logsdon RG, Liu R. Perceptions and beliefs about the role of physical activity and nutrition on brain health in older adults. Gerontologist. 2009;49(Suppl 1):S61–71. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Krueger KR, Hoganson G, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Early and late life cognitive activity and cognitive systems in old age. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2005;11(4):400–407. doi: 10.1017/S1355617705050459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Beckett LA, Barnes LL, Schneider JA, Bach J, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Individual differences in rates of change in cognitive abilities of older persons. Psychol Aging. 2002;17(2):179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Arnold SE, Schneider JA, Kelly JF, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(2):234–240. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Leurgans SE, Boyle PA, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Neurodegenerative basis of age-related cognitive decline. Neurology. 2010;75(12):1070–1078. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f39adc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Yu L, Trojanowski JQ, Chen EY, Boyle PA, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. TDP-43 pathology, cognitive decline, and dementia in old age. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(11):1418–1424. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.3961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]