Summary

Population attributable fraction (PAF) is widely used to quantify the disease burden associated with a modifiable exposure in a population. It has been extended to a time-varying measure that provides additional information on when and how the exposure’s impact varies over time for cohort studies. However, there is no estimation procedure for PAF using data that are collected from population-based case-control studies, which, because of time and cost efficiency, are commonly used for studying genetic and environmental risk factors of disease incidences. In this paper, we show that time-varying PAF is identifiable from a case-control study and develop a novel estimator of PAF. Our estimator combines odds ratio estimates from logistic regression models and density estimates of the risk factor distribution conditional on failure times in cases from a kernel smoother. The proposed estimator is shown to be consistent and asymptotically normal with asymptotic variance that can be estimated empirically from the data. Simulation studies demonstrate that the proposed estimator performs well in finite sample sizes. Finally, the method is illustrated by a population-based case-control study of colorectal cancer.

Keywords: Case-control study, Kernel smoother, Population attributable fraction, Time-varying

1. Introduction

Disease prevention programs often need to prioritize risk factors for public health preventive intervention. It is therefore critical to assess the impact of exposure to risk factors on disease burden at the population level to help guide public health policies. For this purpose, the population attributable fraction (PAF), first introduced by Levin (1953), has been widely used to quantify such impact. It is defined as the proportion of reduction in the disease probability by comparing the current population with a hypothetical population in which the exposure had been eliminated. In essence, PAF integrates both the strength of association between exposure and disease and the prevalence of exposure in the population. Hence it is a more appropriate measure to quantify the impact of risk factors at the population level than association measures such as relative risk or rate ratio. The estimation, inference and application of PAF have been extensively studied, see e.g., Walter (1976); Whittemore (1982); Greenland (1987); Benichou and Gail (1990); Kooperberg (1991); Benichou (2001); and Benichou (2007). In particular, Bruzzi et al. (1985) showed that once one has the relative risk estimates, PAF can be obtained from the distribution of exposure among the cases only. A population-based case-control study based on a random sampling of disease cases and controls provides an estimate of this distribution, and also the required estimates of the relative risks by logistic regression models if the disease is rare.

The PAF is a static measure that evaluates the impact of exposures on binary disease outcome with time-independent risk factors. In practice, disease morbidity or mortality incidences are often collected as time-to-events, and their associated risk exposure may also change over time. For example, in the prevention of incident Human-Immunodeficiency-Virus (HIV) infection, since there is no efficacious vaccine, a combination prevention package that includes several proven prevention tools, targeting various risk exposures, is usually implemented to reduce HIV incidence in a high risk population (Hayes et al., 2014). These prevention tools may include public campaigns addressing social stigma, condom use for safe sex, circumcision, and/or, antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected partners. How these tools are organized in the combination prevention package to maximize its population impact on overall HIV incidence, in a time-changing environment of key risk exposures, is critical to the package’s success. Therefore, rather than Levin’s static PAF, a time-varying PAF, which has the capability to accommodate the outcomes of time-to-event type and the risk exposures being time-varying, may help researchers and policy makers better understand the risk exposures’ impact on disease over time, and provide guidance on the timing of actions or interventions.

Chen et al. (2006) proposed an “attributable hazard function” that extends the PAF to time-to-event. Specifically, let T be the failure time and Z(t) = {Z1(t), …, Zp(t)}T be a p-vector of external time-dependent covariates in the sense of Kalbeisch and Prentice (2011), then the attributable hazard function is defined as follows,

| (1) |

where λ(t) is the hazard function, which is the instantaneous rate of failing at time t, i.e., λ(t) = limΔt→0 Pr(t < T ≤ t + Δt)/Pr(T > t); and λ(t|Z(t) = 0) is the baseline hazard function when Z(t) = 0. This measure inherits the concept of PAF that assesses the risk attributable to exposures. It builds upon the hazard function and captures the time-varying process naturally by measuring the instantaneous attributable risk at time t. Estimation of ϕ(t) requires estimates of hazard ratios, for which methods are well established for cohort data (Andersen et al., 2012), and estimates of the distribution of exposure and failure time (Chen et al., 2006, 2010).

The population-based case-control study is a primary tool for the study of factors related to disease incidence and has been widely used due to its time and cost efficiency. Under this design, a random sample of cases are ascertained in a specified time period, and the control sample is then randomly selected from individuals that are disease-free at the time when the cases are ascertained from the same population (Vandenbroucke and Pearce, 2012). In a seminal paper by Prentice and Breslow (1978), the Cox proportional hazards model is adapted to the case-control study, where they showed that hazard ratios can be obtained consistently from a case-control study. For a specific time t, the time-varying attributable hazard function can be estimated with the hazards ratio and the conditional distribution of exposure among the cases at t. As shown in Section 2.1, this is a generalized result of the PAF for binary outcomes to time-to-event outcomes.

The purpose of this paper is to bridge the gap between the attributable hazard function and the case-control study. We propose a novel kernel-based estimator for ϕ(t) for population-based case-control data in Section 2.1. We establish the large sample properties of the estimator and derive the asymptotic-based variance estimators in Section 2.2 and 2.3. Results from a simulation study for the performance of the proposed estimators are presented in Section 3 and an application of the proposed estimator to a large case-control study of colorectal cancer is shown in Section 4. The paper is concluded with some final remarks.

2. Estimation and Inferences

2.1 Time-varying PAF and Estimation

We assume the effect of Z(t) on the hazard function of T follows the Cox proportional hazards model (Cox, 1972),

| (2) |

where Z(t) is a p-vector of possibly time-dependent covariates and β = (β1, …, βp)T are the corresponding regression coefficients assumed to be independent of t. Covariate Z(t) can be baseline covariates (e.g., sex and genotype), exposures measured at time t (e.g., blood pressure), or any suitable functions of covariates up to time t (e.g., smoking pack-years). Let f(t) be the density function of T and f(t|Z(t) = z) the density function of T given Z(t) = z with corresponding survival functions S(t) = Pr(T > t) and S(t|Z(t) = z) = Pr(T > t|Z(t) = z), respectively. If λ0(t) is continuous, λ(t) = f(t)/S(t) and λ(t|Z(t) = z) = f(t|Z(t) = z)/S(t|Z(t) = z). After some algebra, we can rewrite the attributable hazard function (1) as

| (3) |

where the second equality follows the Cox proportional hazards model (2), FZ|T (z|t) is the distribution function of exposure Z(t) of subjects who fail at time t, and 𝒵 is the space for Z(t). Equation (3) indicates a very close resemblance between ϕ(t) and Levin’s PAF for binary outcome for case-control data (Coughlin et al., 1994). Specifically let D be the binary indicator of disease status, then Levin’s PAF can be re-expressed as

| (4) |

By comparing equations (3) and (4), we can see that ϕ(t) has the same form as Levin’s PAF except that the relative risk is now replaced with the hazard ratio, and the density function of Z in cases is replaced with the density of Z in cases who failed at time t. Thus, ϕ(t) can be regarded as the instantaneous evaluation of Levin’s PAF at time t. This also suggests that if we have β̂, ϕ(t) can be obtained from the exposure distribution in cases only.

Next we describe an estimation procedure for ϕ(t), in which there are two unknown quantities β and FZ|T (z|t) that need to be estimated. Now consider a case-control study with n subjects. As described in our Introduction, the study consists of a random sample from the cases of disease as they occur and a random control sample from the population in which the cases arise. Typically only a small fraction of disease-free individuals is selected while the sampling fraction for cases may be close to unity. Suppose that at a given time, or age, tk, mk = m(tk) cases and nk = n(tk) controls are sampled, for K distinct times. Prentice and Breslow (1978) established that the log-hazard ratio β can be estimated consistently by maximizing the conditional likelihood function

where R(mk, nk) is the set of all subsets of size mk from {1, …, mk+nk} and l = (ll1, …, llmk). This has the same form as a conditional logistic regression model where the outcome is disease status and the matched sets consist of time-matched cases and controls. Based on this observation, Prentice and Breslow (1978) also suggested an alternative means of estimating β by applying an unconditional maximum likelihood method under the logistic regression model to improve efficiency. Specifically, consider a study that consists of n subjects. For the ith subject, i = 1, …, n, let Δi denote the disease status. Treating the time-zero at the date of birth, if Δi = 1, the subject is a case and the time-to-event is his or her age at disease diagnosis. If Δi = 0, the subject is a control and the time-to-event is censored at the current age. We denote this time-to-event by Xi. Now let Zi(Xi) be a p-vector of time-dependent covariates, the logistic regression model, as described in Prentice and Breslow (1978), can be written as

where θ = (α0, α1, β) are intercept and regression parameters. Note that the adjustment of Xi is to account for age-dependent disease risk, and the relationship can be non-linear. Under this situation, other suitable functions such as polynomial or nonparametric functions can be used. If cases and controls are matched, the matching variables (e.g., sex) can also be included as covariates in the logistic regression model (Breslow and Day, 1981). An estimator θ̂ of θ including β, the parameter of interest, can then be obtained by solving the likelihood score equation U(θ) = 0, where

| (5) |

We now turn to estimation of FZ|T (z|t). There are two aspects to consider for the estimation process. First, FZ|T (z|t) cannot be directly estimated based on the observed failure times of cases due to unknown censoring times. However, under the assumption that the censoring time is independent of both the failure time and covariates as derived in Xu and O’Quigley (2000), it can be shown that FZ|T (z|t) = F{Z(t) ≤ z|X = t, Δ = 1}, a quantity that is estimable from cases-only data. Second, it is often unclear what the appropriate distribution is for the exposure given the failure time, thus we consider a non-parametric estimator. In order to accommodate sparse data situations (few cases at some observed failure times) and to increase model exibility, we apply a kernel estimator for FZ|T (z|t) to borrow information across failure times. Together with β̂ obtained from (5), we propose the following estimator for time-dependent population attributable hazard function ϕ(t):

| (6) |

where Kh(x) = K(x/h)/h, K(·) is a kernel function that satisfies ∫ K(x)dx = 1, and h is the bandwidth that controls the spread of weighting window.

2.2 Large Sample Properties

In this section we derive the asymptotic properties of ϕ̂(t; β̂) proposed in (6). We assume the following regularity conditions.

-

A1

The time t is in a range of (0, τ) for a constant τ > 0 such that ST (τ)SC(τ) > 0.

-

A2

Random censoring: the censoring time C is independent of both the failure time T and covariates Z(t) for t ∈ (0, τ).

-

A3

Both the density of failure time fT (t) and the density of censoring time fC(t) are continuous, uniformly bounded, and have second derivatives on (0, τ).

-

A4

The bandwidth satisfies h = ndh0 for constants −1/2 < d < −1/5 and h0 > 0.

-

A5The kernel function K(·) has bounded variation and satisfies the following conditions:

-

A6

Z(·) is bounded almost surely and has uniformly bounded total variation on (0, τ).

-

A7

The ratio of the number of cases n1 and total number of subjects n satisfies n1/n → π0 as n → 1, where 0 < π0 < 1.

We define the following notation.

We use P0 and E0 to denote the probability and expectation with respect to the target population from which cases and controls are sampled. As shown in the proof in Web Appendices, it is also useful to regard cases and controls as members of a second, hypothetical population of individuals whose disease probability is given by n1/n (Whittemore, 1995; van der Laan, 2008). We use P* and E* to denote the probability and expectation with respect to this hypothetical population. Let p0 = P0(T ≤ C) and π0 = P*(T ≤ C). Then the limit of Bn(t) and Dn(t) are denoted by B(t) = fT (t)SC(t)π0/p0 and D(t; β) = {∫ze−βTz dFZ|T (z|t)} fT (t)SC(t)π0/p0, respectively.

We summarize the main results, namely consistency and asymptotic normality of ϕ̂(t), in the following two theorems.

Theorem 1

Suppose that assumptions A1 – A7 are satisfied. Then ϕ̂(t; β̂) is uniformly consistent for ϕ(t; β0) for t ∈ (0, τ), where ϕ(t; β0) is the true value of ϕ(t) as defined in (1).

Theorem 2

Suppose that assumptions A1 – A7 are satisfied. Then converges weakly to a zero-mean Gaussian process, and the limiting variance

for t ∈ (0, τ).

The proofs of Theorem 1 and 2 are provided in Web Appendix A and B. Briefly, the idea is to express Sn(t) into two parts:

and study the properties of the two parts separately. In Web Appendix B, we show that the first term vanishes as n → ∞, while the second term converges weakly to a zero-mean Gaussian process. Thus the large sample properties of Sn(t) depend only on the second term. However, in practice with finite sample size, the bandwidth could be considerably large even in large samples. Therefore, in estimation of the variance, the effect of the first term in the variance cannot be ignored even though asymptotically its contribution to the overall variance is negligible.

2.3 Variance Estimation

One natural estimator for σ2(t) can be obtained by substituting its expectation components with the corresponding empirical estimators and parameter β with its estimators:

As we argued in the previous section, the bandwidth might not be close to zero in finite samples, and the variance estimator needs to account for the contribution from . The variance estimator with finite sampling correction is

where , Î(β̂) is the estimated information matrix for β, and is the estimated efficient influence function for β. The consistency of σ̂*2(t; h) is summarized in the following theorem. The proof and derivation of the correction terms in σ̂*2(t; h) are provided in Web Appendix C.

Theorem 3

Suppose that assumptions A1 – A7 are satisfied. Then both σ̂2(t) and σ̂*2(t; h) are uniformly consistent for σ2(t), for t ∈ (0, τ).

Based on this variance estimator, we can construct the pointwise 100(1 − α)% confidence intervals for ϕ̂(t):

| (7) |

where z1−α/2 is the 100(1 − α)th percentile of the standard normal distribution.

In practice it is also often of interest to construct simultaneous 100(1 − α)th percentile confidence bands. However, it is not straightforward to calculate the theoretical confidence bands given the structure of the estimator. Here we provide an approach using resampling techniques adapted from Lin et al. (1994). Consider a process

where Gi, i = 1, 2, …, n, are n independent standard normal variables. It can be shown that for any time point t ∈ (0, τ), the limiting distribution of Ŝ(t) conditional on the observed data {X, Δ, Z} = {Xi, Δi, Zi(Xi), i = 1, 2, 3, …, n} is the same as Sn(t), by the Lindeberg-Feller theorem and verifying a tightness criterion. Indeed, the variance of Ŝ(t) is

Thus the distribution of Sn(t) can be approximated by simulating a large number of realizations from Ŝ(t) through repeatedly generating {Gi}. Then the critical value for 100(1 − α)th percentile simultaneous confidence bands can be calculated based on these simulations:

and the corresponding confidence bands are

2.4 Kernel and Bandwidth Selection

Since a kernel smoother is involved, the performance of the estimator depends on choices of the kernel function and the bandwidth. It is known that bandwidth choice is critical to the adequacy of the kernel estimation, while the kernel function has much less impact. We use the Epanechnikov kernel given its optimization property (Marron and Nolan 1989), and perform the sensitivity analysis using Gaussian and Uniform kernels. We use a “leave-one-out” cross-validation bandwidth optimizer (Bierens 1983) for automatic bandwidth selection. In particular, let

which is the estimator of ϕ(Xj) computed with all but the jth subject. Then the cross-validation criterion is given by

A cross-validation bandwidth is obtained by minimizing CV (h) with respect to h,

This approach generally works well in practice, however, the theoretical properties of ĥCV and ϕ̂(−j)(Xj; ĥCV) are hard to track. Instead, we use a variant of this approach by adopting a finite grid search, which usually has adequate performance yet assures consistency and asymptotic normality of ϕ̂(−j)(Xj; ĥCV) (Bierens, 1983, 1987). Specifically, we optimize h on a set of pre-specified grid points, h1 < h2 < … < hK, such that CV (ĥCV) = inf{CV (hi), i = 1, 2, …, K}.

3. Simulations

We conducted simulation studies to evaluate the finite sample performance of the proposed estimator ϕ̂(t; β̂) for case-control data. Each simulation was conducted by generating a population of interest, sampling case-control data from the population, and calculating the estimators based on the case-control data. We first generated a population with 20,000 subjects. For each subject, we generated a univariate covariate Z(t), a failure time T, and a censoring time C. We considered both the time-independent covariate, Z(t) = Z, and time-varying covariate, Z(t) = 0.02Zt, where Z ~ Bernoulli or Uniform distribution. We then generated the failure time T based on the Cox model (2) with a Weibull baseline hazard λ0(t) = (ν/η)(t/η)ν−1, where ν and η are given below. We also generated independent censoring time C from truncated normal distribution in [1, 100], where mean and variance were chosen to yield desirable censoring percentages. The observed age at onset X was the minimum of T and C, and the disease status Δ = 1 if T ≤ C and Δ = 0 if T > C. We obtained the case-control sample by randomly sampling 1000 cases (Δ = 1) from the population, and 1000 controls with age matched to the cases within five-year intervals (frequency match). Thus the observed data for analysis consist of X, Z, and Δ. We estimated β using conventional logistic regression with adjustment of age. We obtained ϕ̂(t; β̂) and σ̂*2(t; h) using the Epanechnikov kernel and the bandwidth from the proposed automatic cross-validation approach. We also obtained estimators with a range of fixed bandwidths to evaluate the performance of the automatic bandwidth selector.

We considered four simulation scenarios: (I) Early onset common disease with binary exposure, where the baseline hazard parameters were set as η = 40 and ν = 2, Z from a Bernoulli distribution with p = 0.3 and p = 0.6, and β0 = log 2 and log 3, and the censoring time was set to yield a 30% censoring probability; (II) Late onset less common disease with binary exposure, where the baseline hazard parameters were set as η = 70 and ν = 9, Z from a Bernoulli distribution with p = 0.3 and p = 0.6, and β0 = log 2 and log 3, and the censoring time was set to yield a 70% censoring probability; (III) Late onset less common disease with continuous exposure, which was the same as scenario II except that Z was from uniform (0, 4) and β0 = log(1.3) and log(1.6); (IV) Late onset less common disease with continuous time-dependent exposure, which was the same as scenario 3 except that the covariate was time-varying Z(t) = 0.02Zt. For each simulation scenario, a total of 2,000 simulated data sets were generated.

We assessed the performance of the proposed estimator by calculating the following summary statistics: bias, empirical standard deviation (SD), asymptotic-based standard error (ASE), and 95% coverage probability at selected age t. Specifically, the bias was calculated by taking the absolute difference between the true value of ϕ(t) and the mean of ϕ̂(t; β̂). The empirical SD was the empirical standard deviation of ϕ̂(t; β̂), and ASE was the average of ϕ̂(t; β̂) over the 2,000 simulated datasets. The 95% pointwise coverage probability was the proportion of 95% estimated confidence intervals obtained by using equation (7) that covered the true value ϕ(t) at time t.

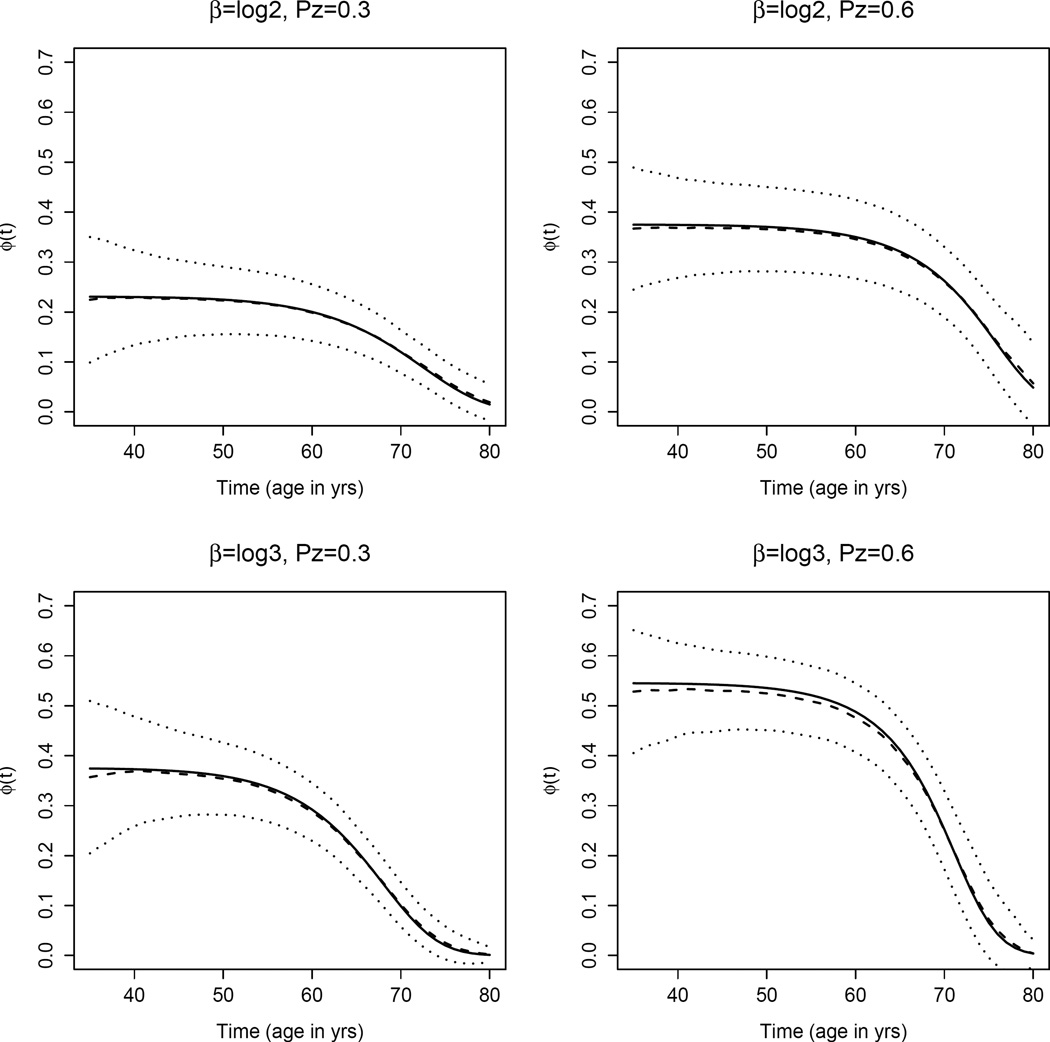

Table 1 shows the results of summary statistics for scenarios I and II for binary covariate Z. There is little bias for the proposed estimator under both scenarios across a wide range of ages. The ASE is close to the empirical standard deviation and the estimated coverage probabilities are generally close to 95%, suggesting that our proposed estimator and the asymptotic distribution-based variance estimator perform well. To have a full view of ϕ̂(t), as an illustration we plotted the proposed estimator of ϕ(t) with 95% pointwise confidence intervals against time t for the late onset disease scenario (Figure 1). It can be seen that ϕ(t) decreases monotonically with time and ϕ̂(t) generally overlaps the true values over the relevant age ranges. As the exposure becomes more common or the odds ratio becomes larger, the curve shifts higher indicating that the time-varying attributable hazard due to exposure is greater. Furthermore, the curve decreases faster with time t. This is because subjects who had the exposure experienced diseases at an earlier age, leaving fewer subjects with exposure in the older age ranges.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of ϕ̂(·; β̂) with binary Z under Scenario I and II.

| Scenario I: Early onset common disease | Scenario II: Late onset less common disease | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Age (yrs) | Biasa | SDb | ASEc | CP(%)d | Age (yrs) | Bias | SD | ASE | CP(%) |

| β0 = log 2, pz = 0.3 | 10 | 0.0008 | 0.0366 | 0.0359 | 94.0 | 40 | 0.0028 | 0.0640 | 0.0628 | 92.2 |

| 20 | 0.0012 | 0.0310 | 0.0317 | 95.2 | 50 | 0.0016 | 0.0399 | 0.0394 | 94.5 | |

| 30 | 0.0000 | 0.0288 | 0.0285 | 94.2 | 60 | 0.0017 | 0.0319 | 0.0314 | 95.3 | |

| 40 | 0.0016 | 0.0270 | 0.0272 | 93.8 | 70 | 0.0013 | 0.0256 | 0.0252 | 94.8 | |

| β0 = log 2, pz = 0.6 | 10 | 0.0025 | 0.0426 | 0.0435 | 95.2 | 40 | 0.0045 | 0.0638 | 0.0628 | 93.1 |

| 20 | 0.0019 | 0.0406 | 0.0414 | 95.3 | 50 | 0.0058 | 0.0471 | 0.0468 | 94.5 | |

| 30 | 0.0009 | 0.0397 | 0.0402 | 95.2 | 60 | 0.0051 | 0.0426 | 0.0424 | 95.2 | |

| 40 | 0.0004 | 0.0421 | 0.0415 | 94.6 | 70 | 0.0027 | 0.0414 | 0.0408 | 93.8 | |

| β0 = log 3, pz = 0.3 | 10 | 0.0019 | 0.0413 | 0.0403 | 94.5 | 40 | 0.0004 | 0.0817 | 0.0777 | 93.2 |

| 20 | 0.0007 | 0.0355 | 0.0349 | 94.8 | 50 | 0.0040 | 0.0444 | 0.0450 | 94.6 | |

| 30 | 0.0014 | 0.0333 | 0.0324 | 93.9 | 60 | 0.0019 | 0.0349 | 0.0345 | 94.5 | |

| 40 | 0.0018 | 0.0310 | 0.0306 | 93.5 | 70 | 0.0031 | 0.0270 | 0.0268 | 93.3 | |

| β0 = log 3, pz = 0.6 | 10 | 0.0024 | 0.0393 | 0.0392 | 94.6 | 40 | 0.0088 | 0.0664 | 0.0654 | 91.6 |

| 20 | 0.0014 | 0.0393 | 0.0385 | 94.2 | 50 | 0.0074 | 0.0439 | 0.0440 | 94.6 | |

| 30 | 0.0004 | 0.0433 | 0.0428 | 95.0 | 60 | 0.0079 | 0.0403 | 0.0402 | 94.3 | |

| 40 | 0.0029 | 0.0573 | 0.0545 | 93.1 | 70 | 0.0011 | 0.0513 | 0.0511 | 94.0 | |

Bias: Absolute difference between the true value of ϕ(t) and the mean of ϕ̂(t; β̂);

SD: Sampling standard deviation;

ASE: Mean of asymptotic-based standard error estimates;

CP: Coverage probability of 95% pointwise confidence intervals.

Figure 1.

A plot of ϕ(t) (solid lines) and mean of ϕ̂(t) (dash lines) with 95% pointwise confidence intervals (dotted lines) over 2,000 simulated data sets against time t (age in years), under Scenario II: late onset disease with binary covariate.

Table 2 shows the summary statistics of proposed estimators under Scenario III (time-independent continuous covariate) and IV (time-dependent continuous covariate). Similar to Table 1, the proposed estimator has little bias. The proposed standard error estimator is very close to the empirical standard deviation, and the coverage probabilities of pointwise confidence intervals are close to 95% over a wide range of time, suggesting that the proposed estimator performs well. We also evaluated our proposed estimators across a range of fixed bandwidths (Web Table 1). As expected, when a smaller bandwidth is used, the bias tends to be smaller while the variance is larger, and when a larger bandwidth is used, the bias tends to be larger, especially at late ages, and the variance is smaller. The cross-validation selected bandwidths balance the bias and variance, and yield satisfactory estimates. We also want to point out that while we observe the trends of bias and variance in association with bandwidth selection, the differences are generally minor. This suggests that the proposed estimators are fairly robust over a wide range of bandwidths in our settings.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of ϕ̂(·; β̂) with continuous Z.

| Scenario III: Time-independent Z | Scenario IV: Time-dependent Z | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Age (yrs) | Biasa | SDb | ASEc | CP(%)d | Age (yrs) | Bias | SD | ASE | CP(%) |

| β0 = log 1.3 | 40 | 0.0068 | 0.0640 | 0.0627 | 93.8 | 40 | 0.0028 | 0.0557 | 0.0555 | 93.8 |

| 50 | 0.0076 | 0.0528 | 0.0531 | 95.5 | 50 | 0.0016 | 0.0490 | 0.0477 | 93.8 | |

| 60 | 0.0064 | 0.0499 | 0.0501 | 95.4 | 60 | 0.0002 | 0.0478 | 0.0476 | 94.1 | |

| 70 | 0.0038 | 0.0466 | 0.0466 | 94.7 | 70 | 0.0018 | 0.0485 | 0.0485 | 95.0 | |

| β0 = log 1.6 | 40 | 0.0089 | 0.0535 | 0.0527 | 93.2 | 40 | 0.0005 | 0.0578 | 0.0543 | 91.3 |

| 50 | 0.0087 | 0.0402 | 0.0402 | 94.4 | 50 | 0.0022 | 0.0385 | 0.0381 | 94.1 | |

| 60 | 0.0074 | 0.0379 | 0.0387 | 95.0 | 60 | 0.0039 | 0.0372 | 0.0366 | 94.4 | |

| 70 | 0.0025 | 0.0433 | 0.0451 | 94.9 | 70 | 0.0024 | 0.0507 | 0.0496 | 93.3 | |

Bias: Absolute difference between the true value of ϕ(t) and the mean of ϕ̂(t; β̂);

SD: Sampling standard deviation;

ASE: Mean of asymptotic-based standard error estimates;

CP: Coverage probability of 95% pointwise confidence intervals.

4. An Application to a Case-Control Study of Colorectal Cancer

The Genetics and Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer Consortium (GECCO) is composed of a number of well-characterized prospective cohorts and case-control studies of colorectal cancer (CRC) (Peters et al., 2013). This consortium aims to both accelerate the discovery of colorectal cancer-related variants and perform thorough epidemiologic evaluations of new susceptibility loci via gene-environment interaction analyses. Key clinical and environmental data have been harmonized across all studies. Due to the fact that colorectal cancer is less common, almost all studies in GECCO are case-control studies. For illustration, we used a subset of the data set that includes 5498 subjects (2742 cases and 2756 controls) from three population-based case-control studies, for which controls are frequency matched on age and sex and the primary outcome is the case-control status of colorectal cancer.

In this analysis, we focused on three smoking variables: smoking status (ever-smokers vs never-smokers), years-since-quit-smoking (≤ 10 years vs > 10 years and never-smokers), and pack-years (> = 22.5 vs < 22.5; among ever-smokers). We also investigated the association between risk of CRC and other variables including obesity (body mass index, BMI, > 30 kg/m2), family history of CRC (yes/no), and history of diabetes (yes/no), all of which have been shown to be associated with CRC risk. For each of these variables, a logistic regression model was used to estimate its association with CRC, adjusting for age, gender, and study, and the proposed kernel estimators were used to obtain the time-dependent PAF. The Epanechnikov kernel and cross-validation bandwidth were used in the kernel estimation. To test whether the constant hazard ratios hold for the underlying Cox proportional hazards model, an interaction term between time and the risk factor was added to the logistic model and tested. The interaction term was not significantly different with 0 for each of the six risk factors at the 0.05 level (the p-values range from 0.40 to 0.89).

The descriptive statistics of age, sex and risk factors by case-control status are provided in Table 3. The odds ratios (OR) of these risk factors and classic PAF are estimated and provided in the same table. The classic Levin’s PAF estimates and standard errors were calculated using the logistic model-based method as in Benichou and Gail (1990). Age and sex are balanced between cases and controls by study design. Generally cases have a higher percentage of positive family history of CRC, diabetes history, obesity, and smoking than controls. Cases also have a higher average pack-year and shorter years-since-quit-smoking. These variables are all significantly associated with CRC risk at level 0.05, with OR between 1.20 and 1.65. History of diabetes has the highest OR of 1.65; however, the prevalence of exposure is low with 7.5% in cases and 4.7% in controls, which results in an estimated PAF of only 0.029 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.016–0.043). In contrast, pack-year has the highest PAF 0.153 (95% CI: 0.089–0.218), followed by ever-smoking with a PAF of 0.094 (95% CI: 0.042–0.146). Since the OR estimates are close to each other, the differences in PAF results here are mainly driven by the prevalence.

Table 3.

Summary statistics of risk factors by cases and controls for GECCO data

| Variables | Cases | Controls | OR (95% CI) | (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) (Mean, range)a | 70.8 (50 – 91) | 70.9 (50 – 91) | - | - |

| Gender (female) | 73.9% | 74.2% | – | – |

| Family history of CRC | 17.6% | 15.1% | 1.21 (1.04, 1.40) | 0.031 (0.008, 0.055) |

| History of diabetes | 7.5% | 4.7% | 1.65 (1.31, 2.07) | 0.029 (0.016, 0.043) |

| Obesity | 29.5% | 25.7% | 1.21 (1.07, 1.36) | 0.051 (0.020, 0.083) |

| Ever smoking | 55.2% | 50.8% | 1.20 (1.08, 1.34) | 0.094 (0.042, 0.146) |

| Years since quit smoking (≤10 yrs)b | 18.9% | 14.9% | 1.33 (1.15, 1.54) | 0.047 (0.023, 0.070) |

| Pack-year (>= 22.5)c | 53.9% | 46.2% | 1.40 (1.20, 1.63) | 0.153 (0.089, 0.218) |

Age at onset for cases and age at selection for controls;

Compared to > 10 years since quit smoking and never-smokers;

For ever-smokers only.

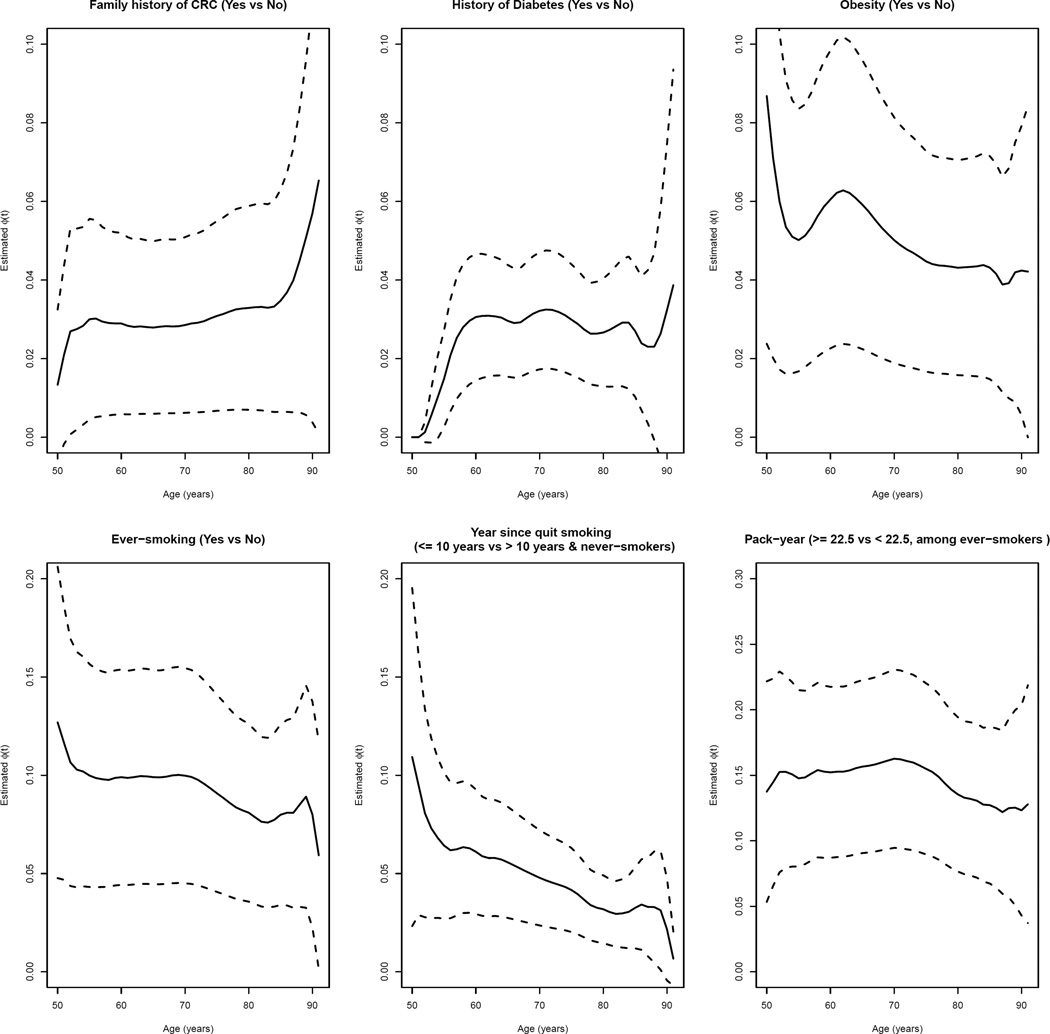

Figure 2 shows the estimated time-varying PAF, ϕ̂(t), for each of the six risk factors on CRC. The attributable hazard functions for family history of CRC and diabetes history are generally at with a slight increase, probably because of increased prevalence of exposure with age. The attributable hazard function for obesity has a decreasing pattern, from 8.8% at age 50 years old to 4.4% at age 80 years old. The attributable hazard function of smoking for CRC decreases slightly over time with ϕ̂(t; β̂) about 12.7% at age 50, dropping slowly to 8.1% at age 80. The estimated curve for year since quit smoking has a steeper decreasing pattern, from 10.9% at age 50 to 3.2% at age 80. The estimated curve for pack-years is approximately at with a slow drop after 80 years old. While some risk factors appear to have generally constant PAF over time, several risk factors such as obesity, smoking and years since quit smoking show a decreasing trend, suggesting an early intervention may possibly reduce risk for early-onset colorectal cancer. Estimates(SE) of time-varying PAF and 95% confidence intervals at selected ages and Levin’s PAF can be found in Web Table 2.

Figure 2.

Time-dependent ϕ̂(·; β̂) versus time t (age in years) for various risk factors. The solid lines are ϕ̂(·) and the dash lines are 95% pointwise confidence intervals.

5. Discussion

In this paper we proposed a kernel-based estimator for time-varying attributable hazard function from population-based case-control studies. We establish the consistency and asymptotic normality of our proposed estimator, and show through extensive simulation the proposed estimator and the analytical variance estimator perform well in finite sample sizes. In addition, our extensive simulation also shows that the proposed estimator is robust with the proposed cross-validation bandwidth selection. A real data application is used to illustrate that the PAF with environmental exposures varies with time.

As ϕ(․) and the classic PAF resemble each other, our estimator has several connections with estimators of classic PAF in case-control studies. Estimation of classic PAF from case-control data could be based on equation (4): odds ratio can be estimated by the logistic regression model, and density of exposure in disease can be estimated by an empirical estimator (Whittemore, 1982; Greenland and Drescher, 1993). The variance can be obtained from a logistic model-based estimator (Benichou and Gail, 1990, 1995) or bootstrap (Greenland et al., 1992). In comparison, our estimator of ϕ(·) is obtained by plugging in the odds ratio estimates from logistic regression model and a kernel estimator of the conditional density function of exposure given T = t. If we used a very large bandwidth that covers the entire time interval, ϕ̂(·) would become a at line and it would be the same as the estimate of the classic PAF through the model-based method by Benichou and Gail (1990).

Several other measures are also proposed to extend classic PAF to a function of time (Chen et al., 2006; Samuelsen and Eide, 2008; Cox et al., 2009; Laaksonen et al., 2010). A closely related measure is ϕ*(t) = 1 − P(T ≤ t|Z = 0)/P(T ≤ t) proposed in the same paper for ϕ(t) by Chen et al. (2006). This measure replaces the hazard rate function in ϕ(t) by the probability of diseased by time t, which is another natural extension of classic PAF for binary outcomes. Both of these measures ϕ(t) and ϕ*(t) are approximately equal when the disease prevalence is low; however they can be quite different when the disease is common. In case-control studies, it is impossible to directly estimate ϕ*(t) based on the data only unless the external disease incidence rate information is used. However, since a case-control study is often preferred in a less common disease situation, if the less common disease assumption indeed holds, our estimation of ϕ(t) can be used to approximate ϕ*(t).

Our estimators can be extended in several directions. First, our proposed estimator was derived under the Cox proportional hazards model. Empirically, the Cox model is fairly robust, as long as the proportionality of the hazards functions between exposed and non-exposed is not seriously violated. However, such a robust nature is not necessarily warranted. A further extension to allow for non-proportionality would be of interest. Second, our estimator requires a random censoring assumption (Kalbeisch and Prentice, 2011), which is key to ensure consistency and asymptotic properties of the estimator. In the case of possible violation, a potential approach to overcome the constraint is to estimate the time-varying PAF stratifying on the covariates that induce the dependent censoring and combine these estimates across strata weighted by its variance. Additional methodological development is needed to relax this assumption.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work is supported by the grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA189532, R01 CA 195789, P01 CA53996, U01 CA137088, R01 CA059045, R01 CA 172415, R01 MH 105857). The authors would like to thank the GECCO Coordinating Center for their generosity of providing the data that is used for illustrating the methods. The detailed funding and acknowledgement for studies that contribute to the GECCO Coordinating Center are provided in Web Appendix D.

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials

Web Appendices and Tables referenced in Sections 2.2, 2.3, 3 and 4, and the R code that implements the proposed methods are available with this paper at the Biometrics website on Wiley Online Library.

References

- Andersen PK, Borgan O, Gill RD, Keiding N. Statistical models based on counting processes. Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Benichou J. A review of adjusted estimators of attributable risk. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2001;10:195–216. doi: 10.1177/096228020101000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benichou J. Biostatistics and epidemiology: measuring the risk attributable to an environmental or genetic factor. Comptes rendus biologies. 2007;330:281–298. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benichou J, Gail MH. Variance calculations and confidence intervals for estimates of the attributable risk based on logistic models. Biometrics. 1990;46:991–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benichou J, Gail MH. Methods of inference for estimates of absolute risk derived from population-based case-control studies. Biometrics. 1995;51:182–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierens HJ. Uniform consistency of kernel estimators of a regression function under generalized conditions. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1983;78:699–707. [Google Scholar]

- Bierens HJ. Kernel estimators of regression functions. Advances in Econometrics: Fifth World Congress. 1987;1:99–144. [Google Scholar]

- Breslow NE, Day N. Statistical methods in cancer research. Vol. 1, The analysis of case-control studies. IARC; 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzi P, Green SB, Byar DP, Brinton LA, Schairer C. Estimating the population attributable risk for multiple risk factors using case-control data. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1985;122:904–914. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Lin DY, Zeng DL. Attributable fraction functions for censored event times. Biometrika. 2010;97:713–726. doi: 10.1093/biomet/asq023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YQ, Hu C, Wang Y. Attributable risk function in the proportional hazards model for censored time-to-event. Biostatistics. 2006;7:515–529. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin SS, Benichou J, Weed DL. Attributable risk estimation in case-control studies. Epidemiologic Reviews. 1994;16:51–64. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox C, Chu H, Muñoz A. Survival attributable to an exposure. Statistics in Medicine. 2009;28:3276–3293. doi: 10.1002/sim.3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S. Variance estimators for attributable fraction estimates consistent in both large strata and sparse data. Statistics in medicine. 1987;6:701–708. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780060607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S, Drescher K. Maximum likelihood estimation of the attributable fraction from logistic models. Biometrics. 1993;49:865–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S, Gefeller O, Kooperberg C, Petitti DB. The bootstrap method for standard errors and confidence intervals of the adjusted attributable risk. Epidemiology. 1992;3:271–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes R, Ayles H, Beyers N, Sabapathy K, Floyd S, Shanaube K, Bock P, Griffith S, Moore A, Watson-Jones D, et al. Hptn 071 (popart): Rationale and design of a cluster-randomised trial of the population impact of an hiv combination prevention intervention including universal testing and treatment–a study protocol for a cluster randomised trial. Trials. 2014;15:1. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalbeisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. Vol. 360. John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kooperberg C, Petitti DB. Using logistic regression to estimate the adjusted attributable risk of low birthweight in an unmatched case-control study. Epidemiology. 1991;2:363–366. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199109000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laaksonen MA, Härkänen T, Knekt P, Virtala E, Oja H. Estimation of population attributable fraction (paf) for disease occurrence in a cohort study design. Statistics in medicine. 2010;29:860–874. doi: 10.1002/sim.3792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ML. The occurrence of lung cancer in man. Acta-Unio Internationalis Contra Cancrum. 1953;9:531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Fleming T, Wei L. Confidence bands for survival curves under the proportional hazards model. Biometrika. 1994;81:73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Peters U, Jiao S, Schumacher FR, Hutter CM, Aragaki AK, Baron JA, Berndt SI, Bézieau S, Brenner H, Butterbach K, et al. Identification of genetic susceptibility loci for colorectal tumors in a genome-wide meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:799–807. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice RL, Breslow NE. Retrospective studies and failure time models. Biometrika. 1978;65:153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsen SO, Eide GE. Attributable fractions with survival data. Statistics in medicine. 2008;27:1447–1467. doi: 10.1002/sim.3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Laan MJ. Estimation based on case-control designs with known prevalence probability. The International Journal of Biostatistics. 2008;4 doi: 10.2202/1557-4679.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbroucke JP, Pearce N. Case–control studies: basic concepts. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2012;41:1480–1489. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter SD. The estimation and interpretation of attributable risk in health research. Biometrics. 1976;32:829–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore AS. Statistical methods for estimating attributable risk from retrospective data. Statistics in Medicine. 1982;1:229–243. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780010305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore AS. Logistic regression of family data from case-control studies. Biometrika. 1995;82:57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Xu R, O’Quigley J. Proportional hazards estimate of the conditional survival function. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 2000;62:667–680. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.