Abstract

Objective

To evaluate warfarin prescription, quality of International Normalized Ratio (INR) monitoring, and of INR control in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and chronic kidney disease.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of patients with newly diagnosed AF in the Veterans Administration (VA) health care system. We evaluated anticoagulation prescription, INR monitoring intensity, and time in and outside INR therapeutic range (TTR) stratified by chronic kidney disease severity (CKD).

Results

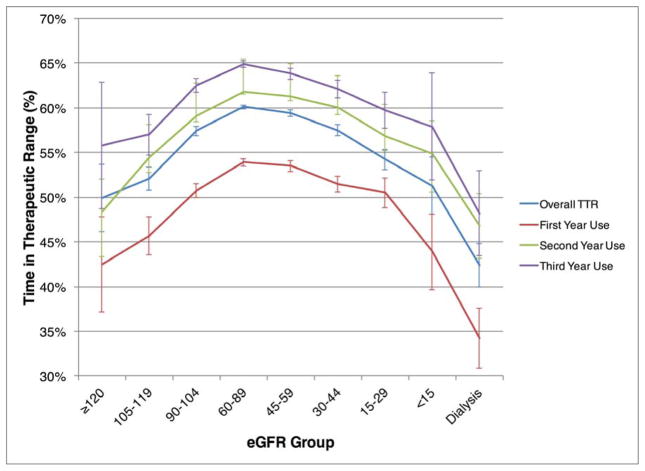

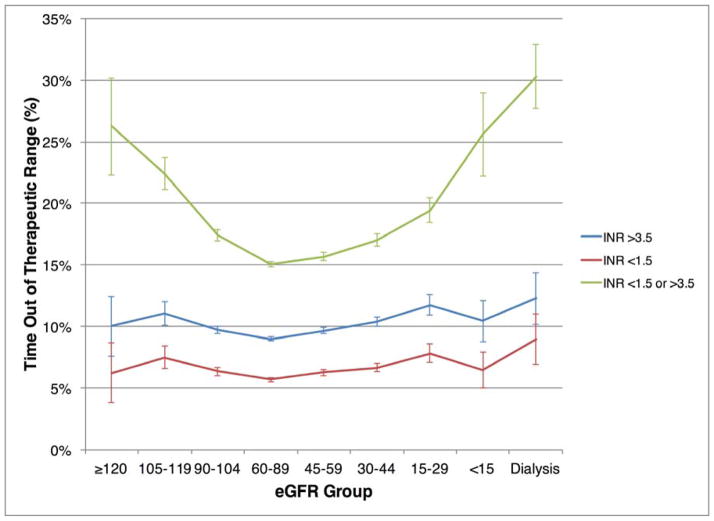

Of 123,188 patients with newly diagnosed AF, use of warfarin decreased with increasing severity of CKD (57.2% to 46.4%), although it was higher among patients on dialysis (62.3%). Although INR monitoring intensity was similar across CKD strata, the proportion with TTR ≥ 60% decreased with CKD severity, with only 21% of patients on dialysis achieving TTR ≥ 60%. After multivariate adjustment, the magnitude of TTR reduction increased with CKD severity. Patients on dialysis had the highest time markedly out of range with INR <1.5 or INR >3.5 (30%); 12% of INR time was > 3.5, and low TTR persisted for up to three years.

Conclusions

There is a wide variation in anticoagulation prescription based on CKD severity. Patients with moderate to severe CKD, including dialysis, have substantially reduced TTR, despite comparable INR monitoring intensity. These findings have implications for more intensive warfarin management strategies in CKD or alternative therapies such as direct oral anticoagulants.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with an increased risk of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter (AF, collectively).1 The prevalence of diagnosed AF among U.S. patients with CKD requiring hemodialysis has been estimated at more than 10%, but may be as high as 40%.2,3

In AF, risk of stroke also increases in the presence of CKD, and CKD has been shown to increase discrimination and classification over the CHADS2 score alone.4 Paradoxically, the risk of bleeding complications in warfarin is also higher in patients with AF, and CKD has been incorporated into several bleeding risk prediction schemata.5,6 While it has been well recognized that CKD impacts both stroke and bleeding risk,7 the impact of CKD on AF disease management and quality outcomes is not well-defined. The combined increased stroke and bleeding risk among warfarin-treated patients with CKD may be due to poor quality of the internationally normalized ratio (INR) control (outside of the optimal range of 2.0 to 3.0). We sought to examine the impact of CKD severity on warfarin prescription, quality of INR monitoring, and INR control.

METHODS

Data sources

The Retrospective Evaluation and Assessment of Therapies in AF (TREAT-AF) study is a retrospective cohort study of patients with newly diagnosed AF treated in the Veterans Administration (VA) health care system8, the largest integrated health system in the United States. Our methods have been previously described.9 We used data from multiple centralized VA patient datasets: 1) the VA National Patient Care Database (NCPD), which contains outpatient, inpatient, and long-term care administrative data representing the universe of VHA users;10 2) the VA Decision Support System (DSS) national pharmacy extract11 3) the VA Fee Basis Inpatient and Outpatient datasets, which capture non-VA care; 4) Medicare inpatient and outpatient institutional claims data (Part A, Part B, Carrier files); and 5) the VHA Vital Status File, which contains validated combined mortality data from VA, Medicare, and Social Security Administration sources. The study was approved by an Institutional Review Board of Stanford University School of Medicine.

Identification of study cohort and predictors

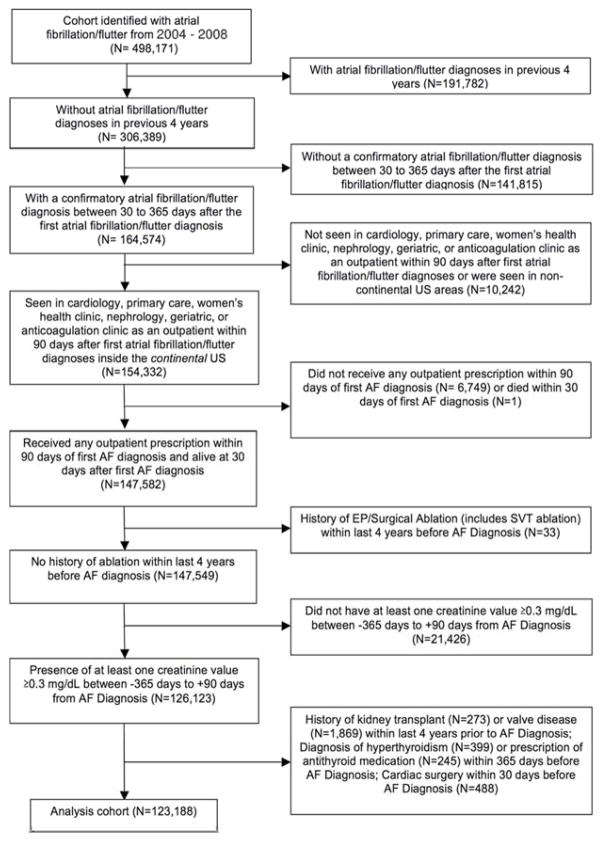

We created a cohort of patients with newly diagnosed AF and evidence of subsequent outpatient VA care. Figure 1 illustrates cohort inclusion and exclusion criteria. We included patients that met the following criteria: 1) primary or secondary diagnosis of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD-9] 427.31 or 427.32) associated with an inpatient or outpatient VA encounter (“index date” of AF diagnosis) between October 1, 2003 and September 30, 2008; 2) confirmatory AF diagnosis in the 30 and 365 days after the index AF diagnosis; 3) at least one primary care, cardiology, women’s health, nephrology, geriatric, or anticoagulation clinic outpatient visit in the continental U.S. in the 90 days post-index date; 4) receipt of warfarin prescription in the 90 days post-index date; 5) baseline creatinine value between −365 days to +90 days from the index date. The study period of 2003–2008 was chosen because this period preceded the introduction of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), thereby reducing selection bias among warfarin-treated patients.

Figure 1.

Cohort Selection Diagram

Medicare linkage

Veterans who were eligible for Medicare benefits could receive INR testing outside of the VA. We therefore searched for outpatient INR monitoring data in the Medicare outpatient files that were linked using a validated algorithm that matched on social security number, gender, and two of three elements of the date of birth (month, day, year).

Exposure

The exposure of interest was stage of CKD. We used a baseline serum creatinine from 365 days before to 90 days after the index AF diagnosis and calculated eGFR using the CKD-EPI formula.12 If there was more than one creatinine value in this period, the closest value to the date of AF was used. Dialysis status was determined using ICD-9 and CPT codes for dialysis related procedures or diagnoses. Our methods, including correction factors based on type of laboratory assay used, have been previously described in detail.9

Outcomes

INR Monitoring Rate

Professional society guidelines recommend that patients have INR monitoring once every month or in four-week intervals.13 We therefore assessed INR monitoring quality by calculating an INR monitoring rate, defined as the proportion of warfarin-issued intervals in which INR testing was performed. As in prior literature, we extended the acceptable period of monitoring to once every 42 days, with a 6 day overlap on the head and tail of a calendar month to allow for situations where stable patients had reasonable INR control even without strict testing based on calendar month.14 This 42-day rolling window for INR testing is used internally within the VA as a quality measure for the minimum acceptable monitoring frequency.

INR monitoring rates were calculated using VA outpatient, Medicare outpatient, VA fee basis, and inpatient INR VA laboratory data. We also included inpatient INR tests that were performed on the date of discharge. To avoid potential underestimation of INR monitoring rates, we also included INR testing identified from VA Fee Basis and Medicare outpatient claims. We restricted our measurement of INR monitoring rate to include only INRs drawn during periods of warfarin exposure. INR eligibility was determined by evaluating outpatient warfarin dispensation from the DSS file and by secondarily evaluating the frequency of INR monitoring. Active treatment with warfarin was determined by filling of warfarin prescriptions. A grace period of 30 days between prescriptions fills was allowed. An INR monitoring episode is the 42-day period starting with the day of the INR test and extending for 42 days total. Inpatient days were excluded from analysis.

Time in Therapeutic Range

The primary outcome was overall time in therapeutic range (TTR) of outpatient warfarin use, which represents the TTR for each patient from index warfarin prescription fill until drug or INR discontinuation. We calculated the TTR using the Rosendaal method, which uses linear interpolation to assign an INR value to each day between successive INR values.15 INR values separated by > 56 days were not interpolated. We used INR values from outpatient and inpatient VA files and restricted our measurement of TTR to use only eligible INRs. Patients were also assumed to have continuously been on warfarin if prescriptions were filled within 30 days from the end of their prior prescription’s supply. Additionally, patients were assumed to have been continuously on warfarin if there was evidence of INR monitoring every 42 days or less. We excluded inpatient hospitalizations from TTR analyses since warfarin is frequently not administered during hospitalizations.14 TTR was also calculated for the first, second, and third full year of warfarin use. In order to minimize selection bias based on patients without any INR gaps, second and third year TTR were not conditioned on having a full measurable TTR in the preceding years.

Secondary outcomes were 1) dispensed warfarin prescriptions identified from DSS within 90 days of AF diagnosis; 2) any use of warfarin within the total follow-up period after AF diagnosis; 3) yearly and total INR monitoring rate; and 4) time out of therapeutic range.

Clinical covariates

Baseline patient-level comorbidities were identified up to four years prior to the date of first AF diagnosis using NCPD, Fee Basis Outpatient Care, and Inpatient encounter files. Descriptions of clinical covariates used are in Appendix A. ICD-9 and CPT codes used to define comorbid conditions are listed in Appendix B.

Statistical analyses

We compared differences in baseline characteristics, warfarin prescription prevalence, INR monitoring rates, and TTR among patients with varying eGFR groups using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests or analyses of variance for continuous variables. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for warfarin prescription within 90 days of AF diagnosis were also calculated using hierarchical logistic regression adjusting for clinical covariates. To estimate the independent association of CKD stage on TTR, we used multilevel mixed-effects linear regression with random intercepts (Stata commend gllamm) clustered by site and adjusted for patient covariates (age, sex, rate, body mass quartile, distance to VA clinics, VA insurance status, mental health conditions, comorbidity index, cancer, anemia, prior bleeding, cardiovascular medications, and CHADS component comorbidities). We performed all analyses with SAS version 9.1 (Cary, NC) and STATA, version 11.0 (College Station, TX).

Role of funding source

The study was funded by an American Heart Association National Scientist Development Grant, Gilead Sciences Cardiovascular Scholars Award, VA Health Services Research & Development Career Development Award, VA MERIT Review Awards. The sponsors were not involved with the study design, data assembly or analysis, or manuscript preparation.

RESULTS

Clinical Characteristics

Out of 498,171 patients identified with AF in 2004–2008, there were 123,188 patients with newly diagnosed AF who met our criteria for analysis (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 72±10 years; 1.6% of patients were women. Patients with lower eGFR were generally older, although patients with eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73m2 or on dialysis groups were younger than patients with more moderate CKD. There were more black patients in the extreme ends of the eGFR distribution. Patients with lower levels of kidney function had higher CHADS2 scores, higher ATRIA bleeding risk scores, and higher Charlson and Selim comorbidity scores. Patients with lower eGFR also had a higher prevalence of coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, prior stroke/TIA, aspirin use, and clopidogrel use. Notably, 9.4% of patients with severely reduced kidney function had a history of stroke or TIA, compared to less than 5% of patients with normal or mildly impaired kidney function. More than three-fourths of all patients with severely reduced kidney function had high ATRIA scores. More dialysis patients had a history of pulmonary embolus or deep venous thrombosis (3.4%) than patients in other eGFR groups.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Kidney Function | P value | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eGFR >=120 (N=278) |

eGFR 105–119 (N=2018) |

eGFR 90–104 (N=13257) |

eGFR 60–89 (N=62174) |

eGFR 45–59 (N=26939) |

eGFR 30–44 (N=13411) |

eGFR 15–29 (N=3787) |

eGFR <15 (N=679) |

Dialysis (N=645) |

|||

| Age, mean (± SD) (years) | 49.0 (11.1) | 54.8 (9.6) | 62.1 (8.4) | 71.6 (9.5) | 76.1 (8.4) | 77.9 (7.9) | 77.2 (8.5) | 72.9 (10.0) | 67.6 (10.2) | <0.001 | |

| Age>75 | 0 (0%) | 46 (2.3%) | 979 (7.4%) | 27,392 (44.1%) | 16,935 (62.9%) | 9,742 (72.6%) | 2,629 (69.4%) | 351 (51.7%) | 192 (29.8%) | <0.001 | |

| Female | 13 (4.7%) | 38 (1.9%) | 203 (1.5%) | 924 (1.5%) | 432 (1.6%) | 284 (2.1%) | 82 (2.2%) | 7 (1.0%) | 8 (1.2%) | <0.001 | |

| mean BMI (kg/m2) | 28.9 | 31.2 | 31.2 | 29.7 | 29.2 | 28.9 | 28.9 | 28 | 28.9 | <0.001 | |

| Race | White | 79 (28.4%) | 941 (46.6%) | 9,264 (69.9%) | 53,698 (86.4%) | 24,486 (90.9%) | 12,244 (91.3%) | 3,346 (88.4%) | 555 (81.7%) | 434 (67.3%) | <0.001 |

| Black | 124 (44.6%) | 499 (24.7%) | 1,069 (8.1%) | 2,952 (4.8%) | 1,292 (4.8%) | 700 (5.2%) | 268 (7.1%) | 81 (11.9%) | 161 (25.0%) | ||

| Physical comorbidities | Anemia | 56 (20.1%) | 239 (11.8%) | 1275 (9.6%) | 7491 (12.1%) | 5224 (19.4%) | 4113 (30.7%) | 1780 (47.0%) | 366 (53.9%) | 380 (58.9%) | <0.001 |

| Cancer (newly diagnosed) | 25 (9.0%) | 143 (7.1%) | 988 (7.5%) | 4527 (7.3%) | 1853 (6.9%) | 899 (6.7%) | 233 (6.2%) | 26 (3.8%) | 43 (6.7%) | <0.001 | |

| Chronic liver disease | 10 (3.6%) | 67 (03.3%) | 226 (1.7%) | 514 (0.8%) | 172 (0.6%) | 79 (0.6%) | 37 (1.0%) | 10 (1.5%) | 19 (3.0%) | <0.001 | |

| Chronic lung disease | 69 (24.8%) | 458 (22.7%) | 2965 (22.4%) | 12350 (19.9%) | 5586 (20.7%) | 3040 (22.7%) | 946 (25.0%) | 126 (18.6%) | 215 (33.3%) | <0.001 | |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 55 (19.8%) | 444 (22.0%) | 3,931 (29.7%) | 23,202 (37.3%) | 12,326 (45.8%) | 7,093 (52.9%) | 2,180 (57.6%) | 319 (47.0%) | 395 (61.2%) | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes | 68 (24.5%) | 541 (26.8%) | 3,688 (27.8%) | 16,201 (26.1%) | 7,946 (29.5%) | 4,790 (35.7%) | 1,608 (42.5%) | 299 (44.0%) | 414 (64.2%) | <0.001 | |

| Heart Failure | 36 (13.0%) | 224 (11.1%) | 1,460 (11.0%) | 7,680 (12.4%) | 4,858 (18.0%) | 3,518 (26.2%) | 1.260 (33.3%) | 207 (30.5%) | 296 (45.9%) | <0.001 | |

| Prior hemorrhage | 21 (7.6%) | 199 (9.9%) | 1070 (8.1%) | 4360 (7.0%) | 2067 (7.7%) | 1186 (8.8%) | 436 (11.5%) | 77 (11.3%) | 168 (26.1%) | <0.001 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 85 (30.6%) | 712 (35.3%) | 5696 (43.0%) | 29722 (47.8%) | 13833 (51.4%) | 7351 (54.8%) | 2137 (56.4%) | 342 (50.4%) | 417 (64.7%) | <0.001 | |

| Hypertension | 132 (47.5%) | 1,031 (51.1) | 7,295 (55.0%) | 37,479 (60.3%) | 18,195 (67.5%) | 9,799 (73.1%) | 2,941 (77.7%) | 529 (77.9%) | 607 (94.1%) | <0.001 | |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 19 (6.8%) | 100 (5.0%) | 852 (6.4%) | 4,668 (7.5%) | 2,736 (10.2%) | 1,877 (14.0%) | 685 (18.1%) | 123 (18.1%) | 178 (27.6%) | <0.001 | |

| Prior Stroke / TIA | 16 (5.8%) | 96 (4.8%) | 583 (4.4%) | 3,405 (4.4%) | 1,959 (7.3%) | 1,075 (8.0%) | 350 (9.2%) | 54 (8.0%) | 75 (11.6%) | <0.001 | |

| Venous Thrombosis | 4 (1.4%) | 46 (2.3%) | 206 (1.6%) | 731 (1.2%) | 353 (1.3%) | 184 (1.4%) | 46 (1.2%) | 8 (1.2%) | 22 (3.4%) | <0.001 | |

| Mental comorbidities | Alcohol abuse | 60 (21.6%) | 357 (17.7%) | 1447 (10.9%) | 2765 (4.5%) | 819 (3.0%) | 322 (2.4%) | 116 (3.1%) | 28 (4.1%) | 15 (7.9%) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 7 (2.5%) | 64 (3.2%) | 318 (2.4%) | 1100 (1.8%) | 456 (1.7%) | 217 (1.6%) | 78 (2.1%) | 16 (2.4%) | 22 (3.4%) | <0.001 | |

| Bipolar disorder | 7 (2.5%) | 74 (3.7%) | 292 (2.2%) | 623 (1.0%) | 247 (0.9%) | 104 (0.8%) | 30 (0.8%) | 6 (0.9%) | 10 (1.6%) | <0.001 | |

| Dementia | 0 | 10 (0.5%) | 95 (0.7%) | 944 (1.5%) | 590 (2.2%) | 323 (2.4%) | 102 (2.7%) | 14 (2.1) | 17 (2.6%) | <0.001 | |

| Major depression | 26 (9.4%) | 248 (12.3%) | 1168 (8.8%) | 3824 (6.2%) | 1540 (5.7%) | 778 (5.8%) | 243 (6.4%) | 41 (6.0%) | 76 (11.8%) | <0.001 | |

| PTSD | 33 (11.9%) | 206 (10.2%) | 1100 (8.3%) | 3011(4.8%) | 1009 (3.8%) | 475 (3.5%) | 139 (3.7%) | 30 (4.4%) | 51 (7.9%) | <0.001 | |

| Schizophrenia | 7 (2.5%) | 72 (3.6%) | 209 (1.6%) | 513 (0.8%) | 174 (0.7%) | 81 (0.6%) | 28 (0.7%) | 4 (0.6%) | 16 (2.5%) | <0.001 | |

| Substance abuse (non-alcohol) | 37 (13.3%) | 166 (8.2%) | 490 (3.7%) | 801 (1.3%) | 199 (0.7%) | 99 (0.7%) | 36 (1.0%) | 17 (2.5%) | 23 (3.6%) | <0.001 | |

| Meds | Antiarrhythmic drug | 37 (13.3%) | 299 (14.8%) | 1,977 (14.9%) | 8,738 (14.1%) | 4,107 (15.3%) | 2,195 (16.4%) | 675 (17.8%) | 128 (18.9%) | 125 (19.4%) | <0.001 |

| AV nodal agent | 226 (81.3%) | 1,593 (78.9%) | 10,307 (77.8%) | 45,313 (72.9%) | 19,702 (73.1%) | 9,951 (74.2%) | 2,912 (76.9%) | 499 (73.5%) | 533 (82.6%) | <0.001 | |

| Aspirin | 87 (31.3%) | 488 (24.2%) | 2,488 (18.8%) | 8,813 (14.2%) | 3,820 (14.2%) | 2,084 (15.5%) | 760 (20.1%) | 144 (21.2%) | 215 (33.3%) | <0.001 | |

| Clopidogrel | 8 (2.9%) | 52 (2.6%) | 507 (3.8%) | 3,076 (5.0%) | 1,631 (6.1%) | 871 (6.5%) | 257 (6.8%) | 36 (5.3%) | 30 (4.7%) | <0.001 | |

| Aspirin+Clopidogrel | 8 (2.9%) | 43 (2.1%) | 294 (2.2%) | 1,207 (1.9%) | 641 (2.4%) | 383 (2.9%) | 126 (3.3%) | 16 (2.4%) | 38 (5.9%) | <0.001 | |

| Other antiplatelet | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.1%) | 30 (0.2%) | 206 (0.3%) | 108 (0.4%) | 76 (0.6%) | 18 (0.5%) | 3 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 | |

| ACE/ARB | 116 (41.7%) | 929 (46.0%) | 6,667 (50.3%) | 31,930 (51.4%) | 15,145 (56.2%) | 7,728 (57.6%) | 1,870 (49.4%) | 250 (36.8%) | 295 (45.7%) | <0.001 | |

| Stain | 71 (25.5%) | 776 (38.5%) | 6,374 (48.1%) | 32,526 (52.3%) | 14,932 (55.4%) | 7,577 (56.5%) | 2,153 (56.9%) | 295 (43.5%) | 360 (55.8%) | <0.001 | |

| Niacin/Fibrate | 11 (4.0%) | 126 (6.2%) | 1001 (7.6%) | 4192 (6.7%) | 1934 (7.2%) | 1017 (7.6%) | 284 (7.5%) | 54 (8.0%) | 61 (9.5%) | <0.001 | |

| Comorbidity Index | Charlson | 0.89 (1.1) | 0.85 (1.0) | 0.81 (1.0) | 0.80 (1.0) | 1.00 (1.1) | 1.34 (1.3) | 1.80 (1.5) | 1.88 (1.4) | 2.75 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Selim | 2.07 (2.1) | 2.05 (2.0) | 2.16 (2.1) | 2.26 (2.1) | 2.63 (2.1) | 3.17 (2.5) | 3.87 (2.8) | 3.85 (2.8) | 6.00 (2.7) | <0.001 | |

| CHADS2 score group | CHADS2 0–1 | 201 (72.3%) | 1,403 (69.5%) | 8,875 (67.0%) | 32,422 (52.2%) | 10,248 (38.0%) | 3,711 (27.7%) | 859 (22.7%) | 196 (28.9%) | 99 (15.4%) | <0.001 |

| CHADS2 2–3 | 73 (26.3%) | 565 (28.0%) | 4,027 (30.4%) | 26,472 (42.6%) | 14,250 (52.9%) | 7,885 (58.8%) | 2,279 (60.2%) | 390 (57.4%) | 434 (67.3%) | ||

| CHADS2 4–6 | 4 (1.4%) | 50 (2.5%) | 355 (2.7%) | 3,280 (5.3%) | 2,441 (9.1%) | 1,815 (13.5%) | 649 (17.1%) | 93 (13.7%) | 112 (17.4%) | ||

| Mean CHADS2 score (mean ± SD) | 0.96 (1.1) | 1.01 (1.1) | 1.10 (1.1) | 1.54 (1.2) | 1.92 (1.2) | 2.24 (1.2) | 2.41 (1.2) | 2.20 (1.2) | 2.57 (1.1) | <0.001 | |

| ATRIA score group | Low (0–3) | 250 (89.9%) | 1,873 (92.8%) | 12266 (92.5%) | 54491 (87.6%) | 21364(79.3%) | 9113 (68.0%) | 151 (4.0%) | 34 (5.0%) | 9 (1.4%) | <0.001 |

| Medium (4) | 22 (7.9%) | 106 (5.3%) | 649 (4.9%) | 2,990 (4.8%) | 1,749 (6.5%) | 1,076 (8.0%) | 414 (10.9%) | 106 (15.6%) | 134 (20.8%) | ||

| High (5–10) | 6 (2.2%) | 39 (1.9%) | 342 (2.6%) | 4,693 (7.6%) | 3,826 (14.2%) | 3,222 (24.0%) | 3,222 (85.1%) | 539 (79.4%) | 502 (77.8%) | ||

| Mean ATRIA bleed score (mean ± SD) | 1.15 (1.4) | 1.01 (1.2) | 1.07 (1.3) | 1.92 (1.6) | 2.59 (1.7) | 3.19 (1.8) | 6.69 (1.9) | 6.54 (1.9) | 6.56 (1.9) | <0.001 | |

Use of Warfarin by CKD Severity

Use of warfarin within 90 days of AF diagnosis decreased with increasing severity of CKD, ranging from 57.2% to 46.4%, although it was higher in patients on dialysis (62.3%) (Table 2). There was a similar pattern among patients receiving warfarin at any point in follow-up. After adjustment for covariates, warfarin use decreased across categories of worsening eGFR in non-dialysis patients (Table 2). Findings were consistent and without statistical interaction within subgroups stratified based on stroke risk (CHADS2 ≥ 1 vs 0), age (≥ 75 vs < 75), and presence or absence of heart failure diagnosis.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Warfarin Prescription, Stratified by Severity of Kidney Disease

| eGFR Group | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥120 (N=278) |

105–119 (N=2018) |

90–104 (N=13257) |

60–89 (N=62174) |

45–59 (N=26939) |

30–44 (N=13411) |

15–29 (N=3787) |

<15 (N=679) |

Dialysis (N=645) |

Total (N=123188) |

|

| Warfarin receipt at 90 days | 57.2% | 60.4% | 61.6% | 56.7% | 55.0% | 52.5% | 52.1% | 46.4% | 62.3% | 56.3% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Any warfarin during follow-up | 61.5% | 68.4% | 70.2% | 64.6% | 62.6% | 59.7% | 58.4% | 52.9% | 69.9% | 64.0% |

|

| ||||||||||

| Unadjusted OR of warfarin receipt at 90 days | 0.83 (0.65–1.06) | 0.95 (0.86–1.04) | (reference group) | 0.82 (0.79–0.85) | 0.76 (0.73–0.80) | 0.69 (0.66–0.72) | 0.68 (.63–0.73) | 0.54 (0.46–0.63) | 1.03 (0.88–1.21) | – |

|

| ||||||||||

| Adjusted OR of warfarin receipt at 90 days | ||||||||||

| Full Cohort | 0.53(0.40–0.71) | 0.80 (0.71–0.90) | (reference group) | 1.11 (1.06–1.16) | 1.15 (1.09–1.21) | 1.06 (1.00–1.12) | 1.14 (1.04–1.25) | 0.78 (0.66–0.93) | 1.08 (0.90–1.29) | – |

| CHADS2 ≥ 1 | 0.58(0.41–0.83) | 0.85 (0.73–0.98) | (reference group) | 1.11 (1.05–1.17) | 1.15 (1.09–1.23) | 1.07 (1.00–1.12) | 1.14 (1.03–1.25) | 0.79 (0.66–0.95) | 1.04 (0.87–1.25) | – |

| CHADS2 = 0 | 0.49(0.30–0.80) | 0.77 (0.63–0.94) | (reference group) | 1.08 (0.995–1.18) | 1.07 (0.96–1.21) | 0.94 (0.78–1.13) | 1.09 (0.77–1.56) | 0.58 (0.32–1.06) | 1.69 (0.49–5.78) | – |

| Age ≥ 75 | – | 0.76 (0.41–1.39) | (reference group) | 1.07 (0.94–1.23) | 1.07 (0.94–1.23) | 0.98 (0.86–1.12) | 1.12 (0.95–1.31) | 0.82 (0.63–1.06) | 1.28 (0.92–1.77) | – |

| Age < 75 | 0.66(0.50–0.88) | 0.91 (0.81–1.02) | (reference group) | 1.01 (0.96–1.06) | 1.02 (0.96–1.08) | 0.95 (0.87–1.04) | 1.02 (0.88–1.19) | 0.70 (0.55–0.90) | 0.96 (0.77–1.20) | – |

| Heart Failure | 0.97(0.43–2.19) | 0.83 (0.59–1.15) | (reference group) | 1.14 (0.995–1.31) | 1.16 (1.01–1.34) | 1.11 (0.96–1.29) | 1.24 (1.02–1.51) | 0.79 (0.57–1.10) | 1.03 (0.77–1.38) | – |

| No Heart Failure | 0.48(0.35–0.66) | 0.80 (0.71–0.91) | (reference group) | 1.10 (1.05–1.16) | 1.14 (1.08–1.21) | 1.05 (0.99–1.12) | 1.13 (1.02–1.26) | 0.79 (0.65–0.97) | 1.15 (0.91–1.45) | – |

OR = odds ratio

INR Monitoring Rate and Time in Therapeutic Range

INR monitoring rates among warfarin-prescribed patients across strata of eGFR were not significantly different, with 85%–87% of non-hospitalized month-equivalent blocks covered with at least one INR laboratory test (Table 3).

Table 3.

Quality of Warfarin-Associated INR Monitoring and Time in INR Therapeutic Range

| eGFR Group | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >=120 | 105–119 | 90–104 | 60–89 | 45–59 | 30–44 | 15–29 | <15 | Dialysis | Total | p-value | |

| Mean INR Monitoring Rate | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

| Full Cohort | 84.5% (n=147) | 86.5% (n=1193) | 86.4% (n=8198) | 85.8% (n=35473) | 85.6% (n=14577) | 85.7% (n=6652) | 86.2% (n=1786) | 85.0% (n=267) | 86.6% (n=334) | 85.8% (n=68627) | 0.2 |

| Heart Failure | 86.3% (n=24) | 84.3% (n=152) | 86.6% (n=966) | 86.6% (n=4768) | 86.4% (n=2801) | 86.2% (n=1844) | 87.0% (n=604) | 86.2% (n=84) | 86.4% (n=153) | 86.5% (n=11369) | 0.96 |

| No Heart Failure | 84.2% (n=123) | 86.9% (n=1041) | 86.4% (n=7232) | 85.7% (n=30705) | 85.4% (n=11776) | 85.5% (n=4808) | 85.8% (n=1182) | 84.4% (n=183) | 86.8% (n=181) | 85.7% (n=57231) | 0.06 |

| Age < 75 | 84.5% (n=147) | 86.4% (n=1173) | 86.5% (n=7727) | 86.0% (n=21873) | 86.4% (n=6272) | 86.4% (n=2225) | 86.5% (n=660) | 84.4% (n=150) | 85.5% (n=254) | 86.2% (n=40481) | 0.67 |

| Age ≥ 75 | 0 | 92.2% (n=20) | 85.7% (n=471) | 85.5% (n=13600) | 85.0% (n=8305) | 85.4% (n=4427) | 86.0% (n=1126) | 85.7% (n=117) | 90.2% (n=80) | 85.4% (n=28146) | 0.26 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Mean Overall TTR | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

| Full Cohort | 49.9% (n=127) | 52.1% (n=1077) | 57.4% (n=7215) | 60.1% (n=29753) | 59.4% (n=11854) | 57.5% (n=5377) | 54.2% (n=1442) | 51.3% (n=203) | 42.4% (n=289) | 58.9% (n=57337) | <0.001 |

| Heart Failure | 46.2% (n=23) | 52.7% (n=139) | 55.1% (n=860) | 57.0% (n=4152) | 55.9% (n=2379) | 55.7% (n=1563) | 52.5% (n=523) | 47.9% (n=66) | 40.0% (n=127) | 55.8% (n=9832) | <0.001 |

| No Heart Failure | 50.7% (n=104) | 52.0% (n=938) | 57.4% (n=6355) | 60.1% (n=25601) | 59.4% (n=9475) | 57.5% (n=3814) | 54.2% (n=919) | 51.3% (n=137) | 42.4% (n=162) | 59.6% (n=47505) | <0.001 |

| Age < 75 | 50.0% (n=127) | 52.0% (n=1059) | 57.3% (n=6828) | 59.8% (n=19075) | 58.4% (n=5404) | 55.2% (n=1906) | 53.6% (n=576) | 50.6% (n=112) | 42.1% (n=219) | 58.4% (n=35306) | <0.001 |

| Age ≥ 75 | 0 | 59.4% (n=18) | 58.4% (n=387) | 60.6% (n=10678) | 60.1% (n=6450) | 58.7% (n=3471) | 54.6% (n=866) | 52.3% (n=91) | 43.4% (n=70) | 59.8% (n=22031) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||||||

| % of patients with Overall TTR >=60% | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Full Cohort | 29.9% (n=38) | 38.4% (n=413) | 50.1% (n=3613) | 54.8% (n=16310) | 53.0% (n=6287) | 48.3% (n=2595) | 42.5% (n=613) | 38.4% (n=78) | 21.1% (n=61) | 24.4% (n=30008) | <0.001 |

| Heart Failure | 30.4% (n=7) | 36.7% (n=51) | 45.7% (n=393) | 48.6% (n=2018) | 45.1% (n=1072) | 44.5% (n=696) | 39.2% (n=205) | 30.3% (n=20) | 18.9% (n=24) | 45.6% (n=4486) | <0.001 |

| No Heart Failure | 29.8% (n=31) | 38.6% (n=362) | 50.7% (n=3220) | 55.8% (n=14292) | 55.0% (n=5215) | 49.8% (n=1899) | 44.4% (n=408) | 42.3% (n=52) | 22.8% (n=37) | 53.7% (n=25522) | <0.001 |

| Age < 75 | 29.9% (n=38) | 38.1% (n=403) | 49.9% (n=3410) | 54.1% (n=10322) | 51.5% (n=2781) | 43.8% (n=834) | 41.5% (n=239) | 39.3% (n=44) | 21.0% (n=46) | 51.3% (n=18117) | <0.001 |

| Age ≥ 75 | 0 | 55.6% (n=10) | 52.5% (n=203) | 56.1% (n=5988) | 54.4% (n=3506) | 50.7% (n=1761) | 43.2% (n=374) | 37.4% (n=34) | 21.4% (n=15) | 54.0% (n=11891) | <0.001 |

Overall TTR could be calculated in 57,337 patients. There was significant variation in mean time in therapeutic range across eGFR strata. The proportion of patients with TTR ≥ 60% was lowest in severe CKD, with only 21.1% of patients on dialysis achieving TTR ≥ 60% (Table 3).

After multivariate adjustment for site and patient covariates, TTR for patients with CKD was below the conditional mean of TTR for all CKD strata relative to eGFR of 60–89 ml/min (eGFR 45–59: −0.7 (−1.2 to −0.3); eGFR 30–44: −2.6 (-.3.2 to −2.0); eGFR 15–29: −5.9 (−7.0 to −.48): eGFR < 15: −8.8 (−11.6 to −5.9); dialysis: −17.7 (−20.1 to −15.3); p < 0.01 for all).

Across all strata of CKD, TTR values were lowest for patients in their first full year of warfarin use (Figure 2). The full first-year TTR was 52.7% (n=33,645), second-year was 60.8% (n=39,503), and third-year was 63.8% (27,719). However, patients with eGFR < 30 or those on dialysis had mean TTRs < 60% across all years of TTR.

Figure 2.

Percent Time in Therapeutic INR Range, Stratified by Year of Warfarin Use

Time Out of INR Therapeutic Range

Figure 3 demonstrates the percent time out of therapeutic range, stratified based on above, below, and above or below INR target range. Across all CKD strata, the majority of patients out of range had more supratherapeutic than subtherapeutic time. Among patients on dialysis, 30% of INR time was markedly out of range (INR <1.5 or INR >3.5), and 12% of INR time was > 3.5.

Figure 3.

Percent Time Out of Therapeutic INR Range

DISCUSSION

In this U.S. population of VA patients with newly-diagnosed AF, we found that: 1) warfarin was prescribed less frequently in patients with moderate to severe CKD not on dialysis; 2) patients on dialysis had higher rates of warfarin prescription than non-dialysis CKD patients, and 3) patients with CKD, including dialysis, had lower TTR and higher time out of therapeutic range, despite similar INR monitoring intensity. These findings indicate that low TTR in CKD is not mediated by poor INR monitoring and may explain the poor bleeding and stroke outcomes observed in AF with CKD.

Our overall TTR ranges in both new and experienced warfarin users were in line with prior VA studies.13 In the ACTIVE-W trial of warfarin versus clopidogrel plus aspirin, achievement of a TTR of 58% was necessary for treatment benefit with warfarin.16 We found that a strikingly low proportion of patients with severe CKD or on dialysis reached this target despite having similar rates of INR monitoring. Prior studies reported TTR in dialysis patients ranging 10–49%.17–19

The mechanism by which CKD affects INR levels is not completely understood. Kidney disease can significantly reduce the non-renal clearance and bioavailability of warfarin.20 Animal studies have demonstrated a significant 40–85% down-regulation of hepatic cytochrome P-450 metabolism in patients with CKD.21 Dreisbach et al. demonstrated a 50% increase in the plasma warfarin S-enantiomer/R-enantiomer ratio among patients with end-stage renal disease.22 Since the S-enantiomer of warfarin is five times as powerful as the R-enantiomer, this may explain lower reported dosage requirements for warfarin in dialysis patients.23 The decreased non-renal clearance of warfarin and a smaller therapeutic dosage range may explain the difficulty in maintaining INR values in therapeutic range for patients with CKD. The predilection for very subtherapeutic INR values in patients with CKD and dialysis is concerning as these patients frequently have comorbidities which place them at increased for stroke. Additionally, subtherapeutic values indicate the need for continued warfarin dose adjustments which potentially increase the risk for supratherapeutic values and bleeding.

Current U.S. guidelines advocate regular monthly INR checks as a quality measure and do not provide explicit guidelines on increasing frequency of monitoring in high-risk populations.13 However, more frequent INR monitoring in patients with CKD may be important for management. A prior VA analysis has found that non-white race, poverty, driving distance, and mental health conditions increased the likelihood of gaps in INR monitoring.23 However, when adjusting for these and other factors, we found that CKD stage was independently associated with a reduction TTR, with dialysis having the largest effect on the conditional mean of TTR.

There may be lessons to learn from other health care systems. A study of patients in Sweden with AF discharged on warfarin after myocardial infarction found that, across all strata of eGFR, warfarin reduced the risk of a composite of death, MI, and ischemic stroke without increasing bleeding risk.24 Sweden has consistently outperformed other countries in anticoagulation quality, and the majority of centers participate in the AuriculA registry and quality improvement program, which uses a standardized algorithm for warfarin dosing.25 In AuriculA, more frequent INR sampling is systematically implemented if therapeutic range has not been achieved.

Paradoxically, patients on the higher end of eGFR also had lower mean TTR values. Reasons for this are unclear, although patients in these strata may have artificially elevated eGFRs owing to low muscle mass. Perhaps medication compliance was lower in these groups, which were composed of younger patients with lower CHADS2 scores. Intra-person variability in rates of metabolism or greater dietary variability in younger patients could also be a source for difficulty in INR management.

Finally, DOACs may have a role in moderate to severe CKD, although their use in this situation is challenging since all approved DOACs are at least partially eliminated by the kidneys. Physicians are left with few options for dialysis patients with atrial fibrillation. Apixaban is the only DOAC approved in the United States for patients on dialysis. However, the reversibility of warfarin, along with the clinical familiarity of physicians with warfarin, have left it a viable therapeutic option for CKD patients who are already at elevated risk of bleeding and require vascular access multiple times per week. The ongoing introduction of DOAC reversal agents, such as idarucizumab, could alter practice patterns.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, these data were obtained from administrative claims data and there may be misclassification of comorbidities. However, we would expect this to be non-differential across strata of CKD, which could attenuate differences but would be unlikely to cause bias. Second, although we captured Medicare INR values, which were present in a small fraction of patients, we did not have access to INR values from Medicare, thereby potentially leading to larger periods of INR interpolation for TTR measurement in Veteran users of Medicare. Third, in addition to the covariates analyzed in the paper, there may also be unidentified confounders, such as frailty, that may not be well ascertained from claims data. Fourth, these data from the VA system may not be generalizable to women or to other health care systems. Fifth, it should be recognized that full TTRs for years one, two, and three of warfarin treatment represent an “on treatment” analysis of patients alive and well enough to remain on warfarin for that duration. Finally, information on albuminuria, the second domain of CKD classification, was unavailable in the vast majority of patients and therefore not considered in our study.

Conclusion

In sum, among patients with newly-diagnosed AF, we found wide variation in anticoagulation prescription based on CKD severity. Patients with moderate to severe CKD, including dialysis, had substantially reduced TTRs, despite comparable INR monitoring intensity. These findings may have implications for more intensive warfarin management strategies in CKD or alternative therapies such as direct oral anticoagulants, which remain mostly unstudied in patients with advanced CKD.

Key Messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Patients with chronic kidney disease and atrial fibrillation are subject to increased risk for hemorrhage and stroke. Balancing the risk of bleeding events with stroke prevention for patients who receive warfarin is particularly challenging in those with chronic kidney disease or on dialysis.

What does this study add?

Although INR monitoring quality is similar across the CKD spectrum, patients with decreasing kidney function spend less time in therapeutic range.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Patients with poor kidney function may require more intensive warfarin monitoring to maximize time in therapeutic range or may require alternative therapies such as direct oral anticoagulants.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding:

Dr. Turakhia is supported by a Veterans Health Services Research & Development Career Development Award (CDA09027-1), an American Heart Association National Scientist Development Grant (09SDG2250647), Gilead Sciences Cardiovascular Scholars Award, and a VA Health Services and Development MERIT Award (IIR 09-092). Dr. Winkelmayer’s work on this project was supported through NIH grant R01DK095024. The content and opinions expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Competing Interest Statement: There are no competing interests that any of the authors have to disclose.

Contributorship Statement: All of the authors had a substantial role in the planning, data acquisition, analysis, and/or writing of the manuscript.

License: The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, a non-exclusive license on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in HEART editions and any other BMJPGL products to exploit all subsidiary rights

References

- 1.Alonso A, Bengtson LG. A rising tide: the global epidemic of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2014;129(8):829–830. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winkelmayer WC, Patrick AR, Liu J, Brookhart MA, Setoguchi S. The increasing prevalence of atrial fibrillation among hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(2):349–357. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tumlin J, Charytan D, Williamson D. Frequency and Distritubtion of Dialysis-Associated Atrial Fibrillation: Results of MiD Study [abstract] J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:35A. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piccini JP, Stevens SR, Chang Y, et al. Renal dysfunction as a predictor of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: validation of the R(2)CHADS(2) index in the ROCKET AF (Rivaroxaban Once-daily, oral, direct factor Xa inhibition Compared with vitamin K antagonism for prevention of stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation) and ATRIA (AnTicoagulation and Risk factors In Atrial fibrillation) study cohorts. Circulation. 2013;127(2):224–232. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.107128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang MC, Go AS, Chang Y, et al. A new risk scheme to predict warfarin-associated hemorrhage: The ATRIA (Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(4):395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJ, Lip GY. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest. 2010;138(5):1093–1100. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boriani G, Savelieva I, Dan GA, et al. Chronic kidney disease in patients with cardiac rhythm disturbances or implantable electrical devices: clinical significance and implications for decision making-a position paper of the European Heart Rhythm Association endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society. Europace. 2015;17(8):1169–1196. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turakhia MP, Hoang DD, Xu X, et al. Differences and trends in stroke prevention anticoagulation in primary care vs cardiology specialty management of new atrial fibrillation: The Retrospective Evaluation and Assessment of Therapies in AF (TREAT-AF) study. Am Heart J. 2013;165(1):93–101.e101. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turakhia MP, Santangeli P, Winkelmayer WC, et al. Increased mortality associated with digoxin in contemporary patients with atrial fibrillation: findings from the TREAT-AF study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(7):660–668. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cowper DC, Hynes DM, Kubal JD, Murphy PA. Using administrative databases for outcomes research: select examples from VA Health Services Research and Development. J Med Syst. 1999;23(3):249–259. doi: 10.1023/a:1020579806511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith MW, Joseph GJ. Pharmacy data in the VA health care system. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60(3 Suppl):92S–123S. doi: 10.1177/1077558703256726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Estes NA, Halperin JL, Calkins H, et al. ACC/AHA/Physician Consortium 2008 Clinical Performance Measures for Adults with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation or Atrial Flutter: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures and the Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (Writing Committee to Develop Clinical Performance Measures for Atrial Fibrillation) Developed in Collaboration with the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(8):865–884. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rose AJ, Hylek EM, Ozonoff A, Ash AS, Reisman JI, Berlowitz DR. Patient characteristics associated with oral anticoagulation control: results of the Veterans AffaiRs Study to Improve Anticoagulation (VARIA) J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(10):2182–2191. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJ, Briët E. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost. 1993;69(3):236–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connolly SJ, Pogue J, Eikelboom J, et al. Benefit of oral anticoagulant over antiplatelet therapy in atrial fibrillation depends on the quality of international normalized ratio control achieved by centers and countries as measured by time in therapeutic range. Circulation. 2008;118(20):2029–2037. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.750000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dlott JS, George RA, Huang X, et al. National assessment of warfarin anticoagulation therapy for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2014;129(13):1407–1414. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quinn LM, Richardson R, Cameron KJ, Battistella M. Evaluating time in therapeutic range for hemodialysis patients taking warfarin. Clin Nephrol. 2015;83(2):80–85. doi: 10.5414/CN108400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pokorney SD, Simon DN, Thomas L, et al. Patients’ time in therapeutic range on warfarin among US patients with atrial fibrillation: Results from ORBIT-AF registry. Am Heart J. 2015;170(1):141–148.e141. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holden RM, Clase CM. Use of warfarin in people with low glomerular filtration rate or on dialysis. Semin Dial. 2009;22(5):503–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2009.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dreisbach AW, Lertora JJ. The effect of chronic renal failure on drug metabolism and transport. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008;4(8):1065–1074. doi: 10.1517/17425255.4.8.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dreisbach AW, Japa S, Gebrekal AB, et al. Cytochrome P4502C9 activity in end-stage renal disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;73(5):475–477. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9236(03)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rose AJ, Miller DR, Ozonoff A, Berlowitz DR, Ash AS, Zhao S, Reisman JI, Hylek EM. Gaps in monitoring during oral anticoagulation: insights into care transitions, monitoring barriers, and medication nonadherence. Chest. 2013;143(3):751–757. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carrero JJ, Evans M, Szummer K, et al. Warfarin, kidney dysfunction, and outcomes following acute myocardial infarction in patients with atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2014;311(9):919–928. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wieloch M, Själander A, Frykman V, Rosenqvist M, Eriksson N, Svensson PJ. Anticoagulation control in Sweden: reports of time in therapeutic range, major bleeding, and thrombo-embolic complications from the national quality registry AuriculA. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(18):2282–2289. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]