Abstract

Rationale:

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a syndrome that is characterized by an inappropriate hyperinflammatory immune response – primary, as a consequence of a genetic defect of NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes or – secondary, in the progression of infections, rheumatic or autoimmune diseases, malignancies or metabolic diseases.

Patient concerns:

We present the case of a secondary HLH due to Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in a splenectomised patient for spherocytosis, a 37-year-old patient who was splenectomised in childhood for spherocytosis, without immuneprophylaxis induced by antipneumococcal vaccine.

Outcomes:

He developed a severe pneumococcal sepsis associated with secondary HLH, with unfavorable outcome and death.

Lessons:

To our knowledge, just 2 similar cases had been published in the literature, none in which the secondary HLH was the consequence of an invasive pneumococcal infection in a splenectomized patient for spherocytosis, and the association of splenectomy with HLH is surprizin.

Keywords: hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, HLH, splenectomized patient, Streptococcus pneumoniae

1. Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a syndrome that is characterized by an inappropriate hyper-inflammatory immune response – primary, as a consequence of a genetic defect of NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes or – secondary, in the progression of infections, rheumatic or autoimmune diseases, malignancies or metabolic diseases. Among HLH-related infections, the most common are the viral infections: Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, other herpes viruses, the viruses of hepatitis B and C, etc., followed by bacterial, parasitic, or fungal infections. Association of secondary HLH to Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in a patient splenectomized for spherocytosis has not been described so far.

2. Case report

We present the case of a male Caucasian patient, aged 37 years, splenectomized for spherocytosis since the age of 4, with no prophylaxis of meningococcal, and pneumococcal infections through vaccination, that was brought to the emergency room for fever, diarrhea, vomiting, rash skin, myalgia, anuria, and marked alteration of his general condition. At the time of admission, on physical examination, the following changes were noticed: facial erythema, purpura on the legs (see Fig. 1), cyanosis of the extremities, jaundice, left basilar crackles, heart rate of 130 beats per minute, blood pressure of 140/100 mm Hg, hepatomegaly, and anuria. The laboratory investigations that were performed revealed the following alterations (at admission and in evolution) that are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Picture from the emergency room that presents the purpura on the legs and skin lesions.

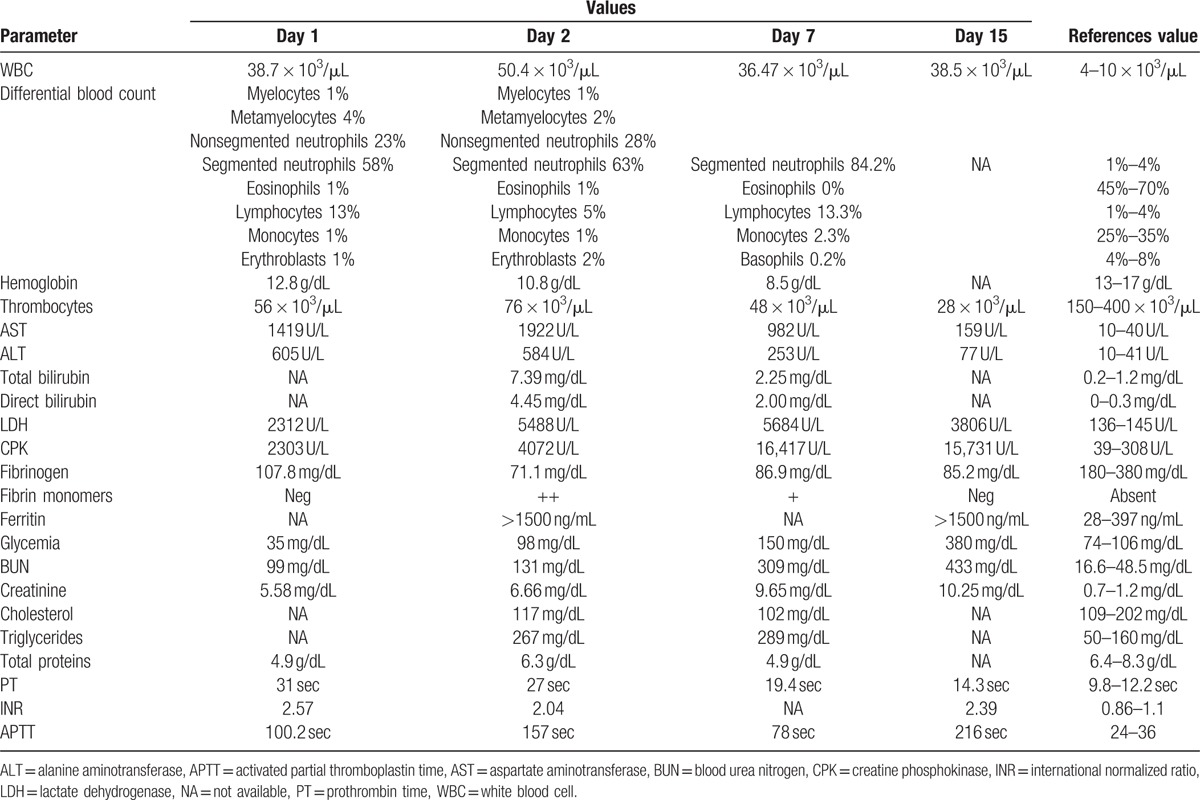

Table 1.

Laboratory studies.

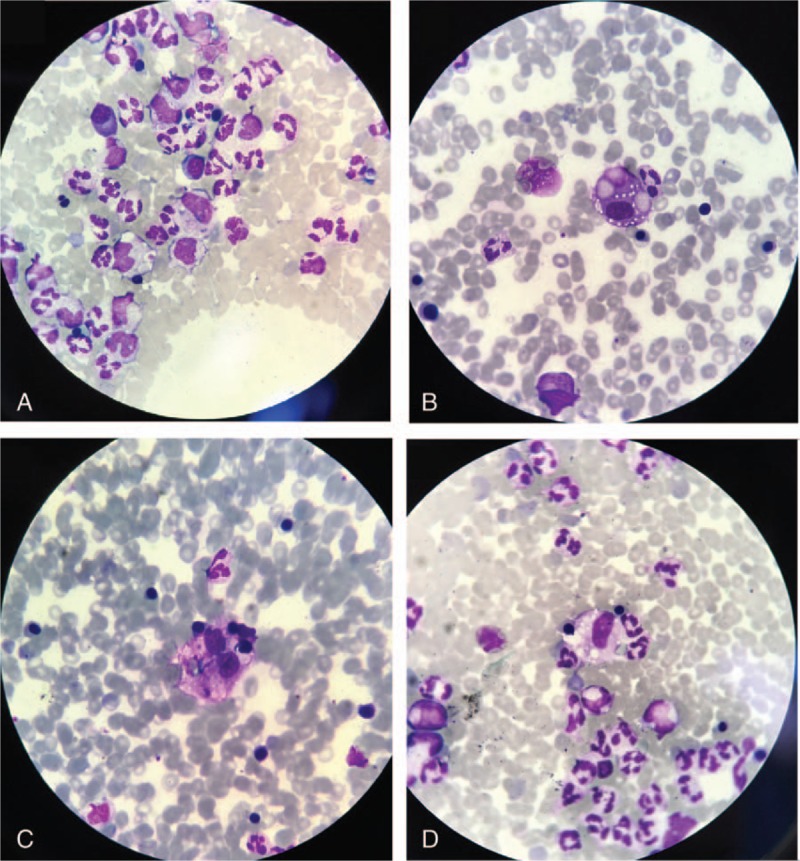

Peripheral smear revealed normochromic normocytic red blood cells, as well as microspherocytes and spherocytes, frequent polychromatophilic macrocytes; erythrocytes with Howell–Jolly bodies (splenectomy), rare dacryocytes (teardrop cells), and schistocytes. Polymorphonuclears with vacuolated cytoplasm are present (toxic appearance), diplo-, encapsulated, and intra- and extracellular gram-positive cocci. Bone marrow sample was harvest and on hematoxylin-eosin stain an increased number of activated macrophages with prominent hemophagocytosis of hematopoietic elements was revealed. Blood cultures and urine cultures were positive for S pneumoniae, resistant to benzylpenicillin, chloramphenicol, erythromycin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, cefotaxime, and intermediate resistance to ceftriaxone, imipenem, sensitive to ofloxacin, vancomycin, moxifloxacin, quinupristin/dalfopristin, levofloxacin, linezolid, rifampicin, sparfloxacin, pristinamycin, amoxicillin, and telithromycin. Viral, parasitic etiologies were excluded, as well as rheumatic diseases, malignant tumors, which may be involved in secondary HLH.

A cardiac ultrasound was performed and revealed no suggestive images of infectious endocarditis or valvular heart disease. Initially, the chest radiography revealed no changes, but in evolution, it showed bilateral alveolar condensation and left pleural effusion.

The case was interpreted as sepsis due to a multidrug-resistant S pneumoniae associated with consumption coagulopathy (bleeding at venepuncture site and epistaxis), acute liver failure, acute renal failure by myoglobinuria, and HLH. In evolution, acute respiratory failure occurred, for which endotracheal intubation of the patient was performed.

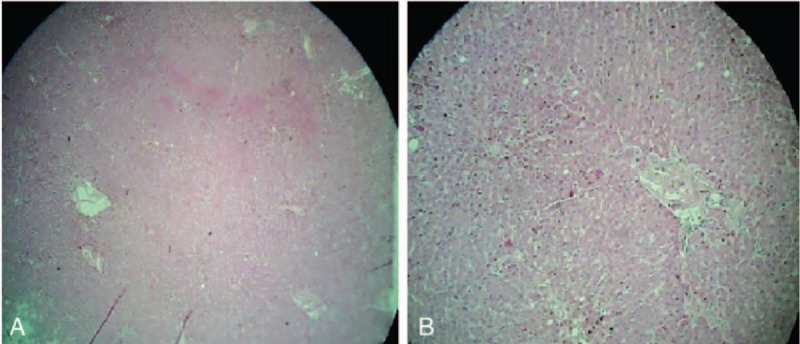

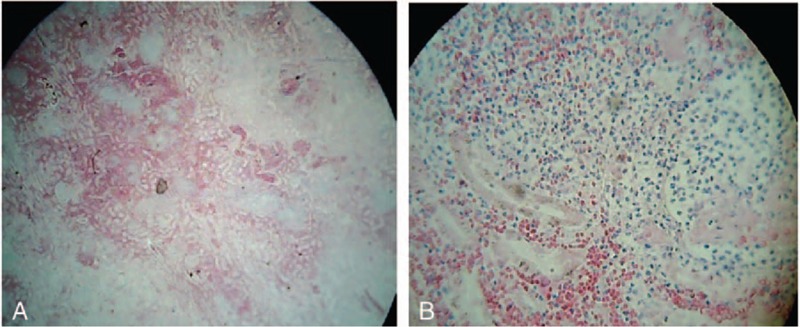

The treatment was started with infusions of macromolecular solutions, hydro-electrolytic rebalancing, packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, and antibiotics – initially, with ultrabroad-spectrum antibiotics, meropenem 2 g/day associated with linezolid 2 × 600 mg/day, thereafter treatment continued with linezolid associated with moxifloxacin 400 mg/day according to antibiogram results, dexamethasone, etoposides 150 mg/m2/day, 3 days, anidulafungin, intravenous immunoglobulin, and daily hemodialysis sessions throughout hospitalization. The evolution was unfavorable with coma, Glasgow Coma Scale of 3, and quadriplegia, the occurrence of bronchopneumonia required endotracheal intubation. During hospitalization, the patient was anuric. Patient death occurred on day 15 of hospitalization. Hematoxylin-eosin and immunohistochemically stainings of liver biopsies taken during the anatomopathological examination revealed the following changes: massive infiltration of portal tract and sinusoids by mononuclear cells. The CD68 stain shows numerous large, irregularly shaped CD68+ cells as being macrophages, cells that are localized both in the portal tract and sinusoids, and with an increased phagocytic activity on lymphocytes, erythrocytes, and polynuclear cells. On CD8 stain, numerous CD8+ lymphocytes were revealed. The conclusion was: the described aspect is in concordance with the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosi. Autopsy examination also revealed bilateral renal papillae necrosis secondary to myoglobinuria, and the presence of hemophagocytosis in bone marrow, and lymph nodes Figs. 2–4.

Figure 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of liver. Magnifications: ×40 (A) and ×100 (B).

Figure 4.

May-Grünwald Giemsa-stained sections of bone marrow. Magnifications: ×100 (A–D).

Figure 3.

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of kidney. Magnifications: ×40 (A) and ×100 (B).

3. Discussions

This case brings into question the risk of splenectomised patients to develop severe systemic infections with encapsulated bacteria, against which the vaccine prophylaxis is essential – for S pneumoniae, H influenzae, and Meningococcus. Lack of vaccination in this patient has enabled the development of severe infections with multidrug-resistant S pneumoniae and the induction of secondary HLH, characterized by an uncontrolled inflammatory response, resulting in patient's death.

Primary HLH has a family, autosomal recessive transmission, and is present in 50,000 new-borns annually. Secondary HLH may be induced by viral (29%), bacterial, or parasitic infections (20%), autoimmune or rheumatic diseases (7%), cancers (27%), and metabolic diseases or immunodeficiency syndromes (6%).[1] Among viral causes, the most common is associated with Epstein–Barr virus. There are also described associations with cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex,[2,3] varicella-zoster virus,[4] herpes virus 8, and associated with HIV infection.[5] There were also published associations with hepatitis B and C viruses,[6,7] influenza viruses,[8] enteroviruses,[9] rotavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome virus,[10] hemorrhagic fevers,[11–15] HIV,[15–18] and so on. Among bacterial infections associated with HLH, there were published associations with Borrelia,[19]Babesia sp,[20]Bartonella sp,[21]Brucella sp,[22] Q fever,[23]Leptospira sp,[24]Listeria monocytogenes,[25]Mycoplasma pneumoniae,[26] and mycobacteria.[27–32] The most frequently described parasitic causes responsible for secondary HLH are: Leishmania sp,[33,34] malaria,[35–37] and Toxoplasma gondii.[38,39] Fungal infections are found to be associated with secondary HLH in HIV-infected patients such as Cryptococcus neoformans,[40]Candida spp,[41] or in patients with renal transplantation-association with disseminated histoplasmosis.[42]

Of the defining HLH criteria established by the Histiocyte Society, respectively, fever, splenomegaly, cytopenia (on at least 2 lines in peripheral blood), hypofibrinemia, hyperferritinemia, hypertriglyceridemia, presence of hemophagocytosis in bone marrow or lymph node, reduction/absence of NK cells activity, and increase in the concentration of soluble IL-2 receptor, CD25,[43] the patient had 5 defining criteria for HLH. The presence of consumption coagulopathy evidenced by the presence of fibrin degradation products is associated with hypofibrinemia and thrombocytopenia in HLH, as well as the liver damage-elevated transaminases, hyperbilirubinemia, activated partial thromboplastin time prolongation. These changes are also present within the septic context, their strict delimitation is not possible.

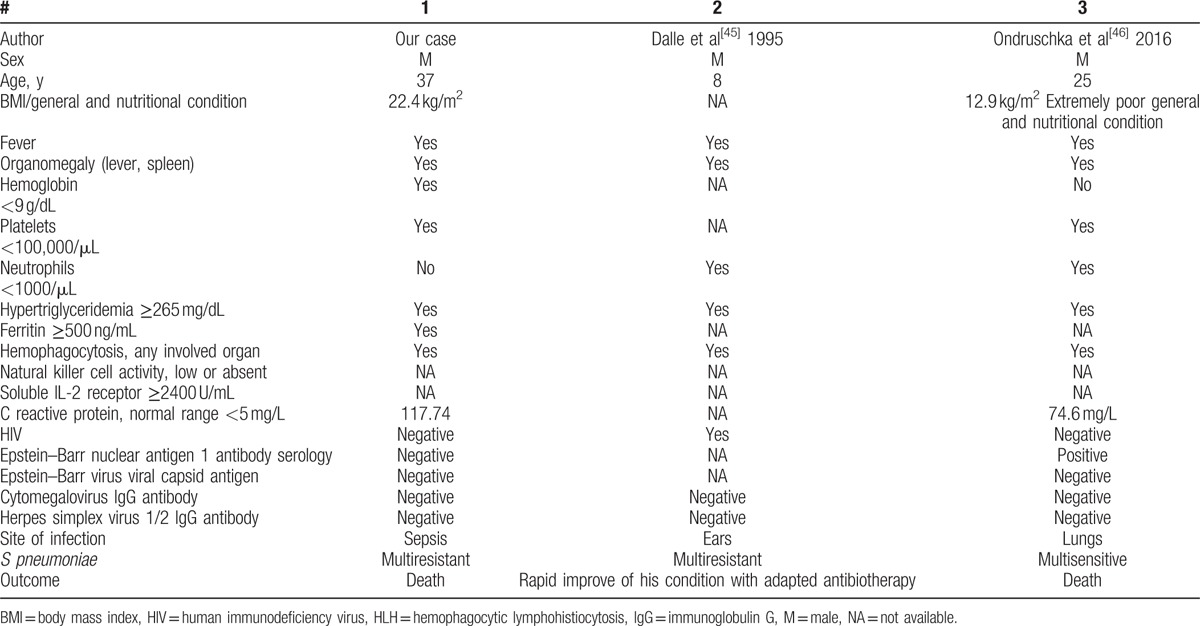

Although the diagnosis of HLH was early, the administration of dexamethasone, intravenous immunotherapy, and administration of etoposides have not improved prognosis, the patient's death occurring on the 15th day of hospitalization. Renal insufficiency due to bilateral renal papillary necrosis has been associated with myoglobinuria as a result of septic myositis, demonstrated by high levels of creatine phosphokinase. There have been described situations in which S pneumoniae infections are responsible for the death of patients with primary HLH.[44] Two cases of HLH associated with a pneumococcal infection had been published (see Table 2). HLH association with hereditary spherocytosis is found in association with viral infections, such as parvovirus B19[47] or Epstein–Barr virus. Moreover, splenectomy is described as a therapeutic method in refractory HLH cases.[48–50]

Table 2.

Clinical and biological characteristics of the 3 cases with HLH due to S pneumoniae.

3.1. Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's next of kin (from his father) for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. The study was accepted by the Ethics Committee of the hospital and they encouraged publishing the article. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

4. Conclusion

The association of sepsis due to S pneumoniae with secondary HLH in a splenectomized patient for spherocytosis should be taken into consideration in similar cases like ours. To our knowledge, no similar cases had been published in the literature, in which the secondary HLH was the consequence of an invasive pneumococcal infection in a splenectomized patient for spherocytosis, and the association of splenectomy with HLH is surprizing. Other similar observations are necessary in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the medical staff from the Hematology and Infectious Disease Department of the Academic Emergency Hospital from Sibiu, and to Dr Ioan Sorin Zaharie for his contribution to the anatomopathological examination.

Footnotes

Abbreviation: HLH = hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

Authorship: VB and RMB contributed equally to this manuscript in terms of acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, conception and design, and drafting the manuscript. Both the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Dhote R, Simon J, Papo T, et al. Reactive hemophagocytic syndrome in adult systemic disease: report of twenty-six cases and literature review. Arthritis Rheum 2003;49:633–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wada Y, Kai M, Tanaka H, et al. Computed tomography findings of the liver in a neonate with Herpes simplex virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Int 2011;53:773–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Yamaguchi K, Yamamoto A, Hisano M, et al. Herpes simplex virus 2-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a pregnant patient. Obstetr Gynecol 2005;105(5 Pt 2):1241–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].van der Werff ten Bosch JE, Kollen WJ, Ball LM, et al. Atypical varicella zoster infection associated with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2009;53:226–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fardet L, Blum L, Kerob D, et al. Human herpesvirus 8-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis 2003;37:285–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Faurschou M, Nielsen OJ, Hansen PB, et al. Fatal virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome associated with coexistent chronic active hepatitis B and acute hepatitis C virus infection. Am J Hematol 1999;61:135–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wu CS, Chang KY, Dunn P, et al. Acute hepatitis A with coexistent hepatitis C virus infection presenting as a virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome: a case report. Am J Gastroenterol 1995;90:1002–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zheng Y, Yang Y, Zhao W, et al. Novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome – a first case report. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2010;82:743–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lindamood KE, Fleck P, Narla A, et al. Neonatal enteroviral sepsis/meningoencephalitis and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: diagnostic challenges. Am J Perinatol 2011;28:337–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nicholls JM, Poon LL, Lee KC, et al. Lung pathology of fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2003;361:1773–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jain D, Singh T. Dengue virus related hemophagocytosis: a rare case report. Hematology 2008;13:286–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Erduran E, Cakir M. Reactive hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Int J Infect Dis 2010;14(Suppl 3):e349.author reply e350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Barut S, Dincer F, Sahin I, et al. Increased serum ferritin levels in patients with Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: can it be a new severity criterion? Int J Infect Dis 2010;14:e50–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tasdelen Fisgin N, Fisgin T, Tanyel E, et al. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: five patients with hemophagocytic syndrome. Am J Hematol 2008;83:73–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cascio A, Todaro G, Bonina L, et al. Please, do not forget secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in HIV-infected patients. Int J Infect Dis 2011;15:e885–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chen TL, Wong WW, Chiou TJ. Hemophagocytic syndrome: an unusual manifestation of acute human immunodeficiency virus infection. Int J Hematol 2003;78:450–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wong CK, Wong BC, Chan KC, et al. Cytokine profile in fatal human immunodeficiency virus tuberculosis Epstein-Barr virus associated hemophagocytic syndrome. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1901–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sun HY, Chen MY, Fang CT, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: an unusual initial presentation of acute HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004;37:1539–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cantero-Hinojosa J, Diez-Ruiz A, Santos-Perez JL, et al. Lyme disease associated with hemophagocytic syndrome. Clin Investig 1993;71:620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gupta P, Hurley RW, Helseth PH, et al. Pancytopenia due to hemophagocytic syndrome as the presenting manifestation of babesiosis. Am J Hematol 1995;50:60–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Karras A, Thervet E, Legendre C. Hemophagocytic syndrome in renal transplant recipients: report of 17 cases and review of literature. Transplantation 2004;77:238–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Karakukcu M, Patiroglu T, Ozdemir MA, et al. Pancytopenia, a rare hematologic manifestation of brucellosis in children. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2004;26:803–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Harris P, Dixit R, Norton R. Coxiella burnetii causing haemophagocytic syndrome: a rare complication of an unusual pathogen. Infection 2011;39:579–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Niller HH. Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) as a late stage of sub-clinical hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): a putative role for Leptospira infection. A hypothesis. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung 2010;57:181–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lambotte O, Fihman V, Poyart C, et al. Listeria monocytogenes skin infection with cerebritis and haemophagocytosis syndrome in a bone marrow transplant recipient. J Infect 2005;50:356–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ishida Y, Hiroi K, Tauchi H, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis secondary to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Pediatr Int 2004;46:174–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Yang WK, Fu LS, Lan JL, et al. Mycobacterium avium complex-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus patient: report of one case. Lupus 2003;12:312–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wali Y, Beshlawi I. BCG lymphadenitis in neonates with familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2012;31:324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].González MJ, Franco AG, Alvaro CG. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis secondary to Calmette-Guèrin bacilli infection. Eur J Intern Med 2008;19:150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Maheshwari P, Chhabra R, Yadav P. Perinatal tuberculosis associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Indian J Pediatr 2012;79:1228–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Su NW, Chen CK, Chen GS, et al. A case of tuberculosis-induced hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a patient under hemodialysis. Int J Hematol 2009;89:298–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Brastianos PK, Swanson JW, Torbenson M, et al. Tuberculosis-associated haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis 2006;6:447–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Martin A, Marques L, Soler-Palacin P, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis associated hemophagocytic syndrome in patients with chronic granulomatous disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009;28:753–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Koubaa M, Maaloul I, Marrakchi C, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome associated with visceral leishmaniasis in an immunocompetent adult-case report and review of the literature. Ann Hematol 2012;91:1143–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sung PS, Kim IH, Lee JH, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) associated with plasmodium vivax infection: case report and review of the literature. Chonnam Med J 2011;47:173–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Saribeyoglu ET, Anak S, Agaoglu L, et al. Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis induced by malaria infection in a child with Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2004;21:267–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Bae E, Jang S, Park CJ, et al. Plasmodium vivax malaria-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a young man with pancytopenia and fever. Ann Hematol 2011;90:491–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Segall L, Moal MC, Doucet L, et al. Toxoplasmosis-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in renal transplantation. Transpl Int 2006;19:78–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Duband S, Cornillon J, Tavernier E, et al. Toxoplasmosis with hemophagocytic syndrome after bone marrow transplantation: diagnosis at autopsy. Transpl Infect Dis 2008;10:372–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Numata K, Tsutsumi H, Wakai S, et al. A child case of haemophagocytic syndrome associated with cryptococcal meningoencephalitis. J Infect 1998;36:118–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bhatia S, Bauer F, Bilgrami SA. Candidiasis-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a patient infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 2003;37:e161–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Lo MM, Mo JQ, Dixon BP, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis associated with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2010;10:687–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Henter JI, Horne A, Arico M, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;48:124–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Sung L, Weitzman SS, Petric M, et al. The role of infections in primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a case series and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 2001;33:1644–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Dale JH, Dofflus C, Leverger G, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome in children infected by HIV. A propos of 3 cases. Arch Pediatr 1995;2:442–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ondruschka B, Habeck JO, Hädrich C, et al. Rare cause of natural death in forensic setting: hemophagocytic syndrome. Int J Legal Med 2016;130:777–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Cheong CS, Gan GG, Chen TM, et al. Parvovirus B19 associated haemophagocytic lymphohistiocitosis in hereditary spherocytosis patient: a case report. JUMMEC 2016;19:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zhang LJ, Zhang SJ, Xu J, et al. Splenectomy for an adult patient with refractory secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Biomed Pharmacother 2011;65:432–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Maciej, Machaczka Splenectomy as a therapeutic approach in refractory hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Biomed Pharmacother 2012;66:159–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Jing-Shi W, Yi-Ni W, Lin W, et al. Splenectomy as a treatment for adults with relapsed hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis of unknown cause. Ann Hematol 2015;94:753–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]