Abstract

Background

Little is known about contraceptive care for the growing population of women veterans who receive care in the Veterans Administration (VA) healthcare system.

Objective

To determine rates of contraceptive use, unmet need for prescription contraception, and unintended pregnancy among reproductive-aged women veterans.

Design and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional, telephone-based survey with a national sample of 2302 women veterans aged 18–44 years who had received primary care in the VA within the prior 12 months.

Main Measures

Descriptive statistics were used to estimate rates of contraceptive use and unintended pregnancy in the total sample. We also estimated the unmet need for prescription contraception in the subset of women at risk for unintended pregnancy. For comparison, we calculated age-adjusted US population estimates using data from the 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG).

Key Results

Overall, 62% of women veterans reported current use of contraception, compared to 68% of women in the age-adjusted US population. Among the subset of women at risk for unintended pregnancy, 27% of women veterans were not using prescription contraception, compared to 30% in the US population. Among women veterans, the annual unintended pregnancy rate was 26 per 1000 women; 37% of pregnancies were unintended. In the age-adjusted US population, the annual rate of unintended pregnancy was 34 per 1000 women; 35% of pregnancies were unintended.

Conclusions

While rates of contraceptive use, unmet contraceptive need, and unintended pregnancy among women veterans served by the VA are similar to those in the US population, these rates are suboptimal in both populations, with over a quarter of women who are at risk for unintended pregnancy not using prescription contraception, and unintended pregnancies accounting for over a third of all pregnancies. Efforts to improve contraceptive service delivery and to reduce unintended pregnancy are needed for both veteran and civilian populations.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4049-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: family planning, VA, contraception

INTRODUCTION

Little is known about contraceptive care or outcomes among the growing population of women veterans who receive health care in the Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system. Counseling and provision of contraceptive services are integral components of primary care for women, as contraception is the most effective means of preventing unwanted pregnancy.1 Unintended pregnancy remains a major public health concern in the US, accounting for nearly half of all pregnancies each year.2 Moreover, it has been linked to a range of adverse health behaviors and outcomes, including maternal tobacco and alcohol use during pregnancy, maternal depression and intimate partner violence, and low birth weight, preterm birth, and infant mortality.1 , 3 , 4 To date, there are no published data about the rate of unintended pregnancy in the female veteran population who use the VA. However, there is reason to suspect that it may be higher than the general US rate, because women who receive VA care are disproportionately from lower income strata, from racial/ethnic minority groups, and have a high prevalence of medical and mental illness5 – 8—characteristics that are associated with less effective contraceptive use and subsequent risk for unintended pregnancy.9 – 14

Although women remain a minority population in the VA (6.5% of all VA patients in 2012), they are among the fastest-growing segments of VA patients, with numbers having nearly doubled over the past decade.15 To better meet the needs of this growing population in a health care system that has historically served men, VA policy requires that all women patients receive comprehensive primary care (i.e., both gender-neutral and gender-specific care) from a provider proficient in women’s health care (i.e., designated women’s health care provider).15 Thus, VA women’s health care providers are expected to be facile in contraceptive management. Hormonal contraceptive methods can be ordered through the VA pharmacy for pick-up or mail delivery, and referral can be made as needed to a gynecologist (either on site, another VA site, or via contract care at a non-VA site) for contraceptive procedures [i.e., sterilization and insertion of intrauterine devices (IUDs) or subdermal implants]. All prescriptions, including contraceptive prescriptions, have a fixed co-pay of $9, and no co-pays for veterans within 5 years of discharge from service in Afghanistan or Iraq or for those disabled by an injury or illness that was incurred during active military service (i.e., service connection); contraceptive devices are provided at no cost.16 , 17 Thus, women VA users have access to the full range of contraceptive methods (although provision for some methods may not necessarily be on site18 , 19). Nonetheless, it remains unclear to what degree their contraceptive needs are being met, as there are no studies that comprehensively assess use of contraception or unintended pregnancy in the VA population. Thus, we conducted the Examining Contraceptive Use and Unmet Need (ECUUN) study to determine rates of contraceptive use, unmet need for prescription contraception, and unintended pregnancy in a national sample of reproductive-age women veterans who receive health care from the VA.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

ECUUN includes a telephone-based, cross-sectional survey conducted with a random sample of women VA users across all regions and Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) in the United States to assess women’s contraceptive use, pregnancy history, and experiences with VA reproductive healthcare. We used VA administrative data from fiscal years 2013 to 2015 to identify women veterans between the ages of 18 and 44 with at least one VA primary care visit in the prior 12 months, resulting in an overall sampling frame of approximately 130,000. Based on a priori analysis, our target study sample was 2300 women to provide 80% power to detect a 5% difference in unmet contraceptive need across subpopulations of interest (e.g., racial/ethnic groups). Every quarter, we “refreshed” the sampling frame to ensure we were capturing women with a visit in the past 12 months; we then randomly selected 1150 of these women to generate a participant recruitment list and mailed study packets to 200 every 2 weeks, continuing this process until our target sample size was met.

Study packets included an invitation letter, a study brochure, and a postage-paid reply card. Women were asked to express interest in or opt out of the study via a toll-free study telephone number or reply card. Two weeks after study packets were mailed, women who did not opt out were called to ascertain their interest in participating, undergo eligibility screening, and provide verbal informed consent. Surveys were conducted by a contracted professional survey research organization between April 2014 and January 2016, using computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) technology. Interviews lasted an average of 45 minutes, and participants received a $30 honorarium. The study was approved by both the VA Pittsburgh and University of Pittsburgh institutional review boards.

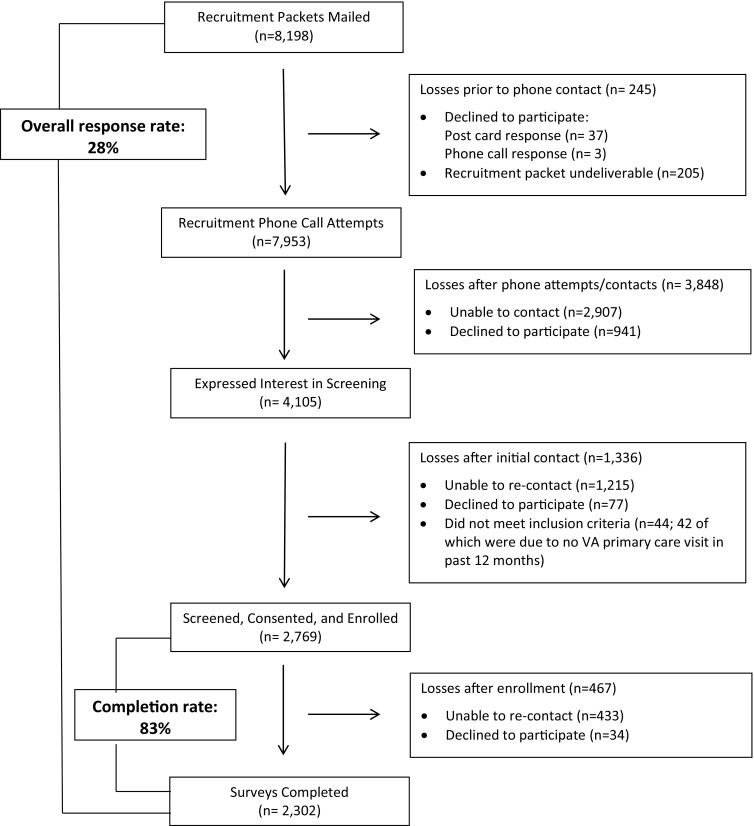

A total of 8198 study invitations were mailed, 2769 women were screened and enrolled, and 2302 completed the survey (Fig. 1). Thus, the overall response rate was 28%, and the survey completion rate among those enrolled was 83%. Using VA administrative data, characteristics of participants (n = 2302) were compared to those of non-participants (n = 5986) using standardized differences, calculated as the difference in means or proportions divided by a pooled estimate of the standard deviation for each characteristic (0.10 considered negligible, 0.20 considered small).20 Participants were similar to non-participants with respect to age, race/ethnicity, marital status, income, presence of medical and mental illness, and geographic region, with standardized differences that were minimal (0.07–0.13, online Appendix 1), suggesting that the ECUUN sample is representative of the larger population of reproductive-age female VA users.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing participant recruitment and response rates.

Measures

To the extent possible, all study measures were equivalent to those used by the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). Current contraceptive use was defined as method use during the month preceding the interview.21 Methods were categorized according to their effectiveness: highly effective methods included female and male sterilization, IUDs, and subdermal implants; moderately effective methods included hormonal methods (pill, ring, patch, and injection); and less effective methods included barrier methods (condoms, diaphragm, cervical cap), fertility-awareness methods, spermicides, and withdrawal. When women reported the use of more than one method, we considered only the most effective.21 Among women veterans at risk for unintended pregnancy (defined as sexually active with a man in the prior 3 months, no history of hysterectomy or infertility, and not pregnant, up to 6 weeks postpartum, or currently trying to get pregnant), we measured contraceptive non-use and unmet need for prescription contraception, defined as the proportion of women using either no method or a less effective, non-prescription method.

Pregnancy rates were computed based on all pregnancies reported in the 12 months prior to the interview. To assess rates of unintended pregnancy, we included a series of questions designed to characterize each pregnancy as either “unwanted,” occurring at the “right time,” “too late,” or “too soon” at the time of conception, or that women “didn’t care” or “didn’t know.” According to convention,2 pregnancies reported as either “unwanted” or having occurred “too soon” were considered unintended.

Demographic and health variables from the survey were also examined to characterize the study population. These variables included age, marital status, education level, annual household income, and history of medical comorbidity, mental health condition, and/or military sexual trauma (MST). Facility-level characteristics of the site where women obtained their care were also examined, including whether the site had a women’s health clinic, the geographic region, and whether the site was a hospital- or community-based outpatient clinic.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine study population characteristics and calculate the rates of contraceptive use, unmet contraceptive need, and unintended pregnancy. We computed the proportion of women from the entire cohort who reported current contraceptive use and determined use of each individual method as well as type of method categorized by clinical effectiveness. Among women at risk of unintended pregnancy, we calculated the proportion of women with an unmet need for prescription contraception. We calculated the annual rates of pregnancy and unintended pregnancy in the prior 12 months per 1000 women and determined the proportion of total pregnancies that were reported as unintended.

For comparison, we calculated general US population rates for contraceptive use, unmet contraceptive need, and unintended pregnancy using data from the 2011–2013 NSFG. The NSFG is a publicly available data set that uses a multistage probability sampling design to select a sample that is representative of the U.S. civilian, non-institutionalized household population aged 15–44 years.22 For the 2011–2013 NSFG, a total of 5601 interviews with women were conducted from September 2011 through September 2013. Interviews were administered in person by trained female interviewers using computer assistance; the survey response rate was 73%.22

Since the VA population differs from the NSFG population with respect to age distribution and educational attainment, we limited the NSFG sample to women aged 20–44 (all ECUUN participants were ≥20 years old) and to women with greater than a high school education or who had a GED, as this is a prerequisite for joining the military.23 , 24 Because rates of contraceptive use and unintended pregnancy vary across age groups,2 and there is a greater proportion of older women in the VA than in the general population, we also determined age-adjusted rates using a direct standardization technique to enhance comparability with the ECUUN rates. Specifically, we calculated the age-specific proportions from the NSFG data and then computed a weighted average by applying those proportions to the ECUUN sample. This adjustment provided an estimated rate for each outcome assuming the US general population had the same age distribution as the ECUUN sample. For unintended pregnancy, we utilized previously published age-specific US rates;2 thus the age-adjusted US rates for pregnancy and unintended pregnancy include women with less than a high school education. We calculated 95% confidence intervals for ECUUN rates using binomial distribution. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Sociodemographic, clinical, and VA facility characteristics for the 2302 study participants are shown in Table 1. Briefly, 51.6% were non-Hispanic white, 28.9% non-Hispanic black, 12.4% were Latina, and 7.1% were “other” race (e.g., Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American). Over half of women veterans (56.2%) reported at least one medical illness, 68.7% reported at least one mental health illness, and 55.0% reported a history of MST. Also shown in Table 1 are age-standardized US population characteristics. Compared to the ECUUN population, US women are more likely to be white and less likely to be black, and have lower educational attainment and higher household income levels.

Table 1.

Population Characteristics

| Characteristic | Women veterans, 2014–2015 (n = 2302)* % | Age-adjusted US population, 2011–2013 (n = 3972)† % |

|---|---|---|

| PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS | ||

| Age, years | ||

| 20–24 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| 25–29 | 16.7 | 16.7 |

| 30–34 | 29.9 | 29.9 |

| 35–39 | 25.4 | 25.4 |

| 40–45‡ | 25.0 | 25.0 |

| Race | ||

| Hispanic | 12.4 | 15.2 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 51.6 | 62.5 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 28.9 | 13.5 |

| Non-Hispanic other/unknown | 7.1 | 8.9 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 23.3 | 19.6 |

| Married | 41.1 | 54.1 |

| Cohabiting | 8.9 | 13.1 |

| Formerly married | 26.7 | 13.2 |

| Education | ||

| High school/technical school | 8.6 | 28.1 |

| Some college, no bachelor’s degree | 38.3 | 34.7 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 53.1 | 37.2 |

| Income§ | ||

| < $20,000 | 20.3 | 17.1 |

| $20,000–59,999 | 54.1 | 39.9 |

| ≥ $60,000 | 25.7 | 43.0 |

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 36.5 | 26.9 |

| 1 | 24.1 | 19.5 |

| 2 | 25.4 | 28.1 |

| 3 | 10.2 | 17.2 |

| ≥4 | 3.8 | 8.4 |

| Has additional (non-VA) insurance | 52.1 | N/A |

| ≥1 Medical conditionǁ | 56.2 | N/A |

| ≥1 Mental health condition¶ | 68.7 | N/A |

| History of military sexual trauma | 55.0 | N/A |

| VA FACILITY CHARACTERISTICS | ||

| VA site has a women’s clinic or center | ||

| Yes | 68.7 | N/A |

| No | 22.1 | N/A |

| Don’t know | 9.2 | N/A |

| Geographic census region | ||

| Northeast | 8.7 | N/A |

| Midwest | 17.8 | N/A |

| South | 53.1 | N/A |

| West | 20.4 | N/A |

| Type of primary care clinic | ||

| Hospital-based clinic | 54.7 | N/A |

| Community-based clinic | 45.3 | N/A |

N/A indicates data/information not available in the NSFG data set

*Missing data for the VA population: marital status (n = 2), income (n = 25)

†Age-specific estimates were obtained from the 2011–2013 NSFG data for women aged 20–44 with at least a high school education or GED and were applied to the VA population age distribution. Age was categorized by 5-year groups as follows: 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, and 40–44. The weighted sample size is 45,947,000

‡A total of 7 women in the ECUUN sample and 2 women in the NSFG sample were 45 years of age by the time of survey completion

§ For NSFG estimates, income was coded based on TOTINC according to the following groups: <$22,500, $22,500 to < $67,500, ≥$67,500

ǁHaving been diagnosed with or received treatment for any of the following: hypertension, history of thromboembolic disease, breast cancer, stroke, liver disease, HIV/AIDS, obesity, diabetes, migraines, systemic lupus erythematosus, or seizure disorders

¶Having been diagnosed with or received treatment for any of the following: depression, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety, or panic disorder

Contraceptive Use

Current contraceptive status, method used, and reasons for contraceptive non-use are shown in Table 2. Overall, 62.3% of women veterans were using contraception in the month prior to the interview. Specifically, 34.4% were using a highly effective method, 17.4% were using a moderately effective method, and 10.2% were using less effective, non-prescription methods. Among the 37.7% of contraception non-users, 13.5% reported not being currently heterosexually active, 7.4% reported hysterectomy, 3.9% reported infertility, and 6.8% reported being either pregnant, postpartum, or seeking pregnancy.

Table 2.

Current Contraceptive Status, Method Used, and Reasons for Contraceptive Non-Use

| Contraception method | Women veterans, age 20–44 2014–2015 (n = 2302)* |

Age-adjusted US population, age 20–44 2011–2013 (n = 3972)† |

US population, age 15–44 2011–2013 (n = 5610)‡ |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95% CI) | % | % | |

| USING CONTRACEPTION § | 62.3 | (60.3, 64.3) | 68.4 | 61.7 |

| Highly effective methods | 34.4 | (32.5, 36.3) | 38.3 | 27.8 |

| Female tubal sterilization | 12.5 | (11.2, 13.9) | 21.7 | 15.5 |

| Male sterilization | 6.0 | (5.1, 7.0) | 8.4 | 5.1 |

| Intrauterine device | 13.6 | (12.2, 15.0) | 7.6 | 6.4 |

| Subdermal implant | 2.2 | (1.6, 2.8) | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| Moderately effective methods | 17.4 | (15.9, 19.0) | 16.5 | 20.4 |

| Pill | 11.2 | (9.9, 12.5) | 13.6 | 16.0 |

| Patch or contraceptive ring | 2.9 | (2.2, 3.6) | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| 3-Month injectable (Depo-Provera™) | 3.3 | (2.6, 4.0) | 1.6 | 2.8 |

| Less effective methods | 10.2 | (8.9, 11.4) | 13.4 | 13.5 |

| Condom | 6.0 | (5.0, 7.0) | 8.7 | 9.4 |

| Periodic abstinence | 1.4 | (0.9, 1.9) | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| Withdrawal | 1.8 | (1.2, 2.3) | 3.3 | 3.0 |

| Other methods‖ | 1.0 | (0.6, 1.4) | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| NOT USING CONTRACEPTION | 37.7 | (35.7, 39.7) | 31.6 | 38.3 |

| Surgically sterile (hysterectomy) | 7.4 | (6.4, 8.5) | 1.1 | 0.7 |

| Infertile (non-surgical)¶ | 3.9 | (3.1, 4.7) | 2.5 | 2.2 |

| Pregnant or postpartum | 2.9 | (2.2, 3.5) | 5.8 | 5.0 |

| Seeking pregnancy | 3.9 | (3.1, 4.7) | 5.4 | 4.5 |

| Never had intercourse | 1.0 | (0.6, 1.5) | 1.9 | 10.8 |

| No intercourse in 3 months before interview | 12.5 | (11.2, 13.9) | 8.6 | 8.2 |

| Intercourse in 3 months before interview | 5.9 | (4.9, 6.8) | 6.4 | 6.9 |

| Missing | 0.2 | (0, 0.4) | 0 | 0 |

CI, confidence interval

*Contraceptive method used in the month of interview among women veterans aged 20–44 who had a VA primary care visit within the 12 months prior to interview

† Age- specific contraception use estimates (contraceptive method used in the month of interview) were obtained from the 2011–2013 NSFG data for women aged 20–44 with at least a high school education or GED and were applied to the VA population age distribution. Age was categorized in 5-year groups as follows: 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, and 40–44. The weighted sample size is 45,947,000

‡ Contraceptive method used in the month of interview among US women aged 15–44; data reported in Daniels K, et al.: Natl Health Stat Report, no. 86, 2015. The weighted sample size is 60,887,000

§ A total of 7 women (0.3) reported using contraception but did not specify method type and are thus not included in individual method reporting

‖ Other methods included spermicide, diaphragm, cervical cap or Today sponge, female condom, and emergency contraception

¶ For the VA population estimates, we only had available information about infertility for women

Age-adjusted US population rates are also shown in Table 2. The rate of any contraceptive use is similar between women veterans (62.3%) and the age-adjusted US population (68.4%). Notably, use of long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods (i.e., IUDs and implants) among VA women is substantially higher than in the adjusted US population (15.8% vs. 8.1%), as is the rate of hysterectomy (7.4% vs. 1.1%), while the rate of tubal sterilization is lower (12.5% vs. 21.7%). The rates for the overall US population aged 15–44, without any adjustment and as published in the literature,21 are also shown in Table 2 for reference.

Unmet Need for Prescription Contraception

Current contraceptive status, method used, and unmet need for prescription contraception for the subset of women at risk for unintended pregnancy are shown in Table 3. Of the 1173 women veterans at risk, 88.5% of women were using some form of contraception. Specifically, 48.8% were using highly effective methods (22.8% were using LARC), 23.4% were using moderately effective methods, and 15.9% were using least effective methods. Thus, 11.5% of women at risk for unintended pregnancy were not using any contraceptive method, and 27.4% were not using prescription contraception.

Table 3.

Women at Risk for Unintended Pregnancy:* Current Contraceptive Status, Method Used, and Unmet Need for Prescription Contraception

| Contraception method | Women veterans, age 20–44 2014–2015 (n = 1173) |

Age-adjusted US population, age 20–44 2011–2013 (n = 2648)† |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95% CI) | % | |

| USING CONTRACEPTION ‡ | 88.5 | (86.7, 90.3) | 90.2 |

| Highly effective methods | 48.8 | (46, 51.7) | 47.7 |

| Female tubal sterilization | 16.8 | (14.7, 18.9) | 25.7 |

| Male sterilization | 9.2 | (7.6, 10.9) | 10.8 |

| Intrauterine device | 19.5 | (17.3, 21.8) | 10.4 |

| Subdermal implant | 3.3 | (2.3, 4.4) | 0.8 |

| Moderately effective methods | 23.4 | (21, 25.9) | 22.2 |

| Pill | 15.7 | (13.6, 17.8) | 18.3 |

| Patch or contraceptive ring | 4.2 | (3.0, 5.3) | 2.0 |

| 3-Month injectable (Depo-Provera™) | 3.6 | (2.5, 4.6) | 1.8 |

| Less effective methods | 15.9 | (13.8, 17.9) | 20.3 |

| Condom | 9.1 | (7.5, 10.8) | 13.1 |

| Periodic abstinence | 2.7 | (1.8, 3.7) | 1.6 |

| Withdrawal | 2.9 | (1.9, 3.9) | 5.2 |

| Other methods§ | 1.1 | (0.5, 1.7) | 0.5 |

| NOT USING CONTRACEPTION | 11.5 | (9.7, 13.3) | 9.8 |

| UNMET NEED FOR PRESCRIPTION CONTRACEPTION ‖ | 27.4 | (24.8, 29.9) | 30.1 |

CI, confidence interval

*Women were considered at risk of unintended pregnancy if they had been sexually active with a man in the prior 3 months, had not had a hysterectomy, and were not infertile, pregnant, postpartum, or trying to get pregnant

† Age-specific contraception use estimates were obtained from the 2011–2013 NSFG data for women aged 20–44 with at least a high school education or GED and at risk of pregnancy and were applied to the VA population age distribution. Age was categorized by 5-year groups as follows: 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, and 40–44. The weighted sample size is 31,385,000

‡ A total of 4 women (0.3) reported using contraception but did not specify method type and are thus not included in individual method reporting

§ Other methods included spermicide, diaphragm, cervical cap or Today sponge, female condom, and emergency contraception

‖ Unmet need for prescription contraception includes the use of a less effective method and no contraceptive use

Age-adjusted US population rates for women at risk of unintended pregnancy are also shown in Table 3. Again, the use of LARC methods among women veterans is substantially higher than that in the adjusted US population (22.8% vs. 11.2%). Contraceptive non-use is similar between women veterans and the US population (11.5% and 9.8%), as is unmet need for prescription contraception (27.4% and 30.1%).

Unintended Pregnancy

The annual rates of pregnancy and unintended pregnancy in the VA population and the general US population are shown in Table 4. The rate of pregnancy in the VA population is 67.3 per 1000 women, and the rate of unintended pregnancy is 26.1 per 1000 women. These rates are lower than those in the age-adjusted US population, where the rate of pregnancy is 96.2 per 1000 women and the rate of unintended pregnancy is 34.4 per 1000 women. However, the proportion of pregnancies that are unintended are similar across both groups, with 37.1% unintended among VA women and 35.2% in the adjusted US population. Previously published rates for the unadjusted overall US population aged 15–44 are also shown in Table 4 for reference.2

Table 4.

Annual Rates of Pregnancy and Unintended Pregnancy

| Women veterans, age 20–44 2014–2015 |

Age-adjusted US population, age 20–44* | US population, age 15–44†

2011 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | ||||

| Pregnancy rate per 1000 women, n | 67.3 | (57.1, 77.6) | 96.2 | 98 |

| Unintended pregnancy rate per 1000 women, n | 26.1 | (19.6, 32.6) | 34.4 | 45 |

| Proportion of pregnancies that were unintended, % | 37.0 | (29.6, 44.3) | 35.2 | 45 |

CI, confidence interval

*Age-specific estimates were obtained from Finer and Zolna: N Engl J Med, 2016, for women aged 20–44 and were applied to the VA population age distribution. Age was categorized by 5-year groups as follows: 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, and 35–44

† Data reported in Finer and Zolna: N Engl J Med, 2016

DISCUSSION

In this representative sample of 2302 women veterans aged 20–44 served by the VA healthcare system, we found that rates of contraceptive use, unmet need for prescription contraception, and unintended pregnancy were similar to those in the US population. Although the annual rate of unintended pregnancy per 1000 women is lower among VA users than the age-adjusted US population, this appears to be driven by a lower overall incidence of pregnancy in women veterans, rather than a greater ability to plan the pregnancies that do occur, as the proportion of pregnancies reported as unintended is similar in both populations. While it is reassuring that unintended pregnancy rates are not higher among women veterans, opportunities for improvement remain. Over a third of pregnancies in both populations are unintended, about 10% of women at risk for unintended pregnancy are not using any method of contraception, and nearly 30% are not using prescription contraception. Further, given the high prevalence of medical and mental illness, which can elevate the risk of negative outcomes associated with unintended pregnancy, unplanned pregnancy may be particularly problematic in the veteran population. Thus, while the VA is making great strides in its care for women veterans, our study findings indicate that further efforts are needed to improve contraceptive service delivery.

A particularly notable finding is the relatively high use of LARC methods by women veterans. In many US settings, women face barriers to accessing LARC methods, including a shortage of trained providers who can insert IUDs and implants, providers applying overly restrictive criteria for IUD candidates, and high upfront costs for the devices.25 – 27 Thus, the finding that women VA users have higher rates of LARC use indicates that the VA has done an admirable job of addressing many of these common barriers. Indeed, the widespread challenges to accessing these highly effective methods recently prompted the National Quality Forum (NQF) to endorse as a clinical performance metric the percentage of women at risk of unintended pregnancy who were provided a LARC method.28 It is important to note when considering the use of performance metrics, however, that contraceptive decisions are highly personal, contextualized, and preference-driven; therefore, there is arguably no clear benchmark for “ideal” rates of use of any particular form of contraception. Care must be taken to ensure, both within and outside the VA, that an emphasis on universal access to IUDs and implants does not result in counseling that promotes these methods at the expense of attention to individual patient preferences.29

Another clinically important finding is the relatively high rate of hysterectomy among women veterans. This is consistent with other recent studies that also found a higher prevalence of early hysterectomy among veterans compared with non-veterans.30 , 31 Some research has suggested that the high rate of hysterectomy among women veterans may be due in part to higher prevalence of sexual assault histories and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which may lead to increased rates of distressing gynecological symptoms and subsequent definitive surgical management.31 Further investigation into these differential rates of hysterectomy is warranted to determine the underlying causes of the higher prevalence observed among VA patients.

While our study provides important clinical and policy-relevant information, there are a few limitations. First, our response rate was lower than that of the NSFG, which used in-person interviews and a complex, two-phase sampling design to raise response rates. However, we did not find any meaningful differences between ECUUN participants and non-participants. Second, ECUUN drew from a clinic-based sample, while NSFG utilizes a population-based sample. Thus, we might expect greater differences in contraceptive use and unintended pregnancy rates, since the ECUUN participants have established health care access and utilization. Third, interviews for ECUUN were conducted mainly between 2014 and 2015, while NSFG interviews were conducted from 2011 to 2013. As the rate of LARC use has been increasing rapidly in recent years,32 , 33 more current NSFG data might indicate less difference in LARC use between the VA and general US populations. Finally, we do not know how cost considerations may have differentially impacted method use. Individual-level costs in both populations vary depending on a number of factors. For women veterans, service connection and time frame of military service affects prescription co-pay requirements. Contraceptive devices require only a co-payment for the insertion visit, making them potentially more financially favorable for those who have prescription co-payment requirements. For the NSFG sample, the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate (which requires no cost-sharing for contraception) was implemented in late 2012 (partway through the NSFG data collection time frame) and was not consistently applied in the early years.34 – 36

In summary, this study provides the first published data on rates of contraceptive use, unmet contraceptive need, and unintended pregnancy in a national sample of women VA users. Although rates are similar to those in the age-adjusted US population, they are suboptimal in that over a third of pregnancies each year are unintended, and nearly 30% of women at risk for unintended pregnancy are not using an effective, prescription contraceptive method. These data provide a global picture of the current state of contraceptive care in the VA and suggest that additional efforts are needed to help women veterans reduce their risk of unintended pregnancy. One strategy might be to routinely ask women about their reproductive intentions or desires as a way of initiating conversation about their reproductive health care needs. The VA plans to implement and evaluate a clinical reminder that prompts providers to periodically assess pregnancy intentions in women with childbearing capacity. Additional analyses using ECUUN data to investigate associations between various patient-, provider-, and facility-level factors and contraceptive use overall, and LARC use in particular, are ongoing and will help to further inform targeted efforts to enhance contraceptive service delivery.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOCX 13 kb)

Contributors

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of the ECUUN research staff (Kristen Rice, MPH, for project coordination and Sarah Daxton, MPW, and Kelly Muthler for participant recruitment). We would also like to acknowledge the University of Pittsburgh, University Center for Social and Urban Research (UCSUR) staff for survey data collection.

Funders

This study was supported by the VA Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) Merit Review Award, IIR 12-124 (PI: Sonya Borrero). Lisa Callegari is supported by a VA Career Development Award, CDA 14-412. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Clinical preventive services for women: closing the gaps. The National Academies Press; 2011.

- 2.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):843–852. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown S, Eisenberg L. The best Intentions: Unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gipson JD, Koenig MA, Hindin MJ. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature. Stud Fam Plan. 2008;39(1):18–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frayne S, Parker V, Christiansen C, et al. Health status among 28,000 women veterans: the VA Women’s Health Program Evaluation Project. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(S3):S40–S46. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00373.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Office of Public Health and Environmental Hazards: Women Veterans Health Strategic Health Care Group. Report of the under Secretary for Health workgroup: Provision of primary care to women veterans. In: Department of Veterans Affairs, ed2008.

- 7.Washington DL, Farmer MM, Mor SS, Canning M, Yano EM. Assessment of the healthcare needs and barriers to VA use experienced by women veterans: findings from the national survey of women Veterans. Med Care. 2015;53(4 Suppl 1):S23–31. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agha Z, Lofgren R, VanRuiswyk J, Layde P. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3252–3257. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frost JJ, Singh S, Finer LB. Factors associated with contraceptive use and nonuse, United States, 2004. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2007;39(2):90–99. doi: 10.1363/3909007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ranjit N, Bankole A, Darroch JE, Singh S. Contraceptive failure in the first two years of use: differences across socioeconomic subgroups. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001;33(1):19–27. doi: 10.2307/2673738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frost JJ, Darroch JE. Factors associated with contraceptive choice and inconsistent method use, United States, 2004. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40(2):94–104. doi: 10.1363/4009408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garbers S, Correa N, Tobier N, Blust S, Chiasson MA. Association between symptoms of depression and contraceptive method choices among low-income women at urban reproductive health centers. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(1):102–109. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0437-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall KS, Kusunoki Y, Gatny H, Barber J. The risk of unintended pregnancy among young women with mental health symptoms. Soc Sci Med. 2014;100:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall KS, Moreau C, Trussell J, Barber J. Young women’s consistency of contraceptive use - Does depression and stress matter? Contraception. 2013;88(5):641–649. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frayne SM, Phibbs CS, Saechao F, et al. Sourcebook: Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 3. Sociodemographics, Utilization, Costs of Care, and Health Profile. Washington DC: Department of Veterans Affairs;2014.

- 16.US Department of Veterans Affairs. Health Benefits Copays. 2017; https://www.va.gov/healthbenefits/cost/copays.asp. Accessed March 7, 2017.

- 17.US Department of Veterans Affairs. Health Benefits, Returning Servicemembers (OEF/OIF/OND). 2017; https://www.va.gov/HEALTHBENEFITS/apply/returning_servicemembers.asp. Accessed March 7, 2017.

- 18.Cope JR, Yano EM, Lee ML, Washington DL. Determinants of contraceptive availability at medical facilities in the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 3):S33–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00372.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katon J, Reiber G, Rose D, et al. VA location and structural factors associated with on-site availability of reproductive health services. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(Suppl 2):S591–597. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2289-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

- 21.Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J, Mosher W. Current contraceptive use and variation by selected characteristics among women aged 15-44: United States, 2011-2013. Natl Health Stat Report. Nov 2015(86):1-14 [PubMed]

- 22.National Center for Health Statistics. 2011-2013 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG): Summary of Design and Data Collection Methods. Hyattsville, MD.

- 23.Department of Defense. Learning About Entrance Requirements. 2016; http://todaysmilitary.com/joining/entrance-requirements. Accessed March 7, 2017.

- 24.Powers R. US Military Enlistment Standards. 2016; https://www.thebalance.com/us-military-enlistment-standards-3354009. Accessed March 7, 2017.

- 25.Callegari LS, Darney BG, Godfrey EM, Sementi O, Dunsmoor-Su R, Prager SW. Evidence-based selection of candidates for the levonorgestrel intrauterine device (IUD) Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM. 2014;27(1):26–33. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.01.130142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foster DG, Barar R, Gould H, Gomez I, Nguyen D, Biggs MA. Projections and opinions from 100 experts in long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. 2015;92(6):543–552. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biggs MA, Harper CC, Malvin J, Brindis CD. Factors influencing the provision of long-acting reversible contraception in California. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(3):593–602. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Quality Forum. Perinatal and Reproductive Health 2015-2016 Final Report. Washington DC: Department of Health and Human Services;2016.

- 29.Dehlendorf C, Bellanca H, Policar M. Performance measures for contraceptive care: what are we actually trying to measure? Contraception. 2015;91(6):433–437. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Callegari LS, Gray KE, Zephyrin LC, et al. Hysterectomy and Bilateral Salpingo-Oophorectomy: Variations by History of Military Service and Birth Cohort. The Gerontologist. 2016;56(Suppl 1):S67–77. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryan GL, Mengeling MA, Summers KM, et al. Hysterectomy risk in premenopausal-aged military veterans: associations with sexual assault and gynecologic symptoms. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(3):352 e351–352 e313. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Branum AM, Jones J. Trends in long-acting reversible contraception use among U.S. women aged 15-44. NCHS data brief, no 188. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. [PubMed]

- 33.Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J, Finer LB. Changes in Use of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive Methods Among U.S. Women, 2009–2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(5):917–927. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bearak JM, Finer LB, Jerman J, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in out-of-pocket costs for hormonal IUDs after implementation of the Affordable Care Act: an analysis of insurance benefit inquiries. Contraception. 2016;93(2):139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finer LB, Sonfield A, Jones RK. Changes in out-of-pocket payments for contraception by privately insured women during implementation of the federal contraceptive coverage requirement. Contraception. 2013;89(2):97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sonfield A. Implementing the federal contraceptive coverage guarantee: progress and prospects. Guttmacher Policy Rev. 2013;16(4):8–12. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 13 kb)