Abstract

In a lung ultrasound examination, interstitial lung lesions are visible as numerous B-line artifacts, and are best recorded with the use of a convex probe. Interstitial lung lesions may result from many conditions, including cardiogenic pulmonary oedema, non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema, or interstitial lung disease. Hence difficulties in the differential diagnostics of the above clinical conditions. This article presents cases of patients suffering from interstitial lung lesions discovered in the course of lung ultrasound examination. The patients were examined with a 3.5–5.0 MHz convex probe and a 7.0–11.0 MHz linear probe. Ultrasound images have been analysed, and differences in the imaging with both probes in patients with interstitial lung lesions have been detailed. The use of a linear probe in patients with interstitial lung lesions (discovered with a convex or a micro-convex probe) provides additional information on the source of the origin of the lesions.

Keywords: interstitial lung disease, B-line artefact, lung ultrasound

Introduction

In a lung ultrasound examination, the involvement of pulmonary interstitium is visible as numerous B-line artifacts forming patterns corresponding to interstitial syndromes, alveolar-interstitial syndromes, or the white lung(1–3). Numerously occurring B-line artifacts are very frequently seen in the ultrasound examination, which generally speaking, is related to a pathological process affecting the pulmonary interstitium. Examples include cardiogenic and non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema, as well as pulmonary fibrosis related to interstitial lung diseases(4–6). Differentiation of the above clinical conditions requires clinical experience and the ability to draw appropriate conclusions from ultrasound examination.

A series of case reports

Case 1

A 67-year-old patient with diagnosed chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, and with a history of chemotherapy and bone marrow transplant. The patient reported exertional dyspnoea gradually intensifying over the last two weeks. No fever. Arterial blood gas test revealed signs of respiratory acidosis. D-dimer was high, BNP within normal standards. Lung ultrasound (LUS) revealed interstitial lesions and small (4–6 mm in diameter) consolidations typical for peripheral pulmonary embolism (Fig. 1, Fig. 2) (confirmed in a angio-CT).

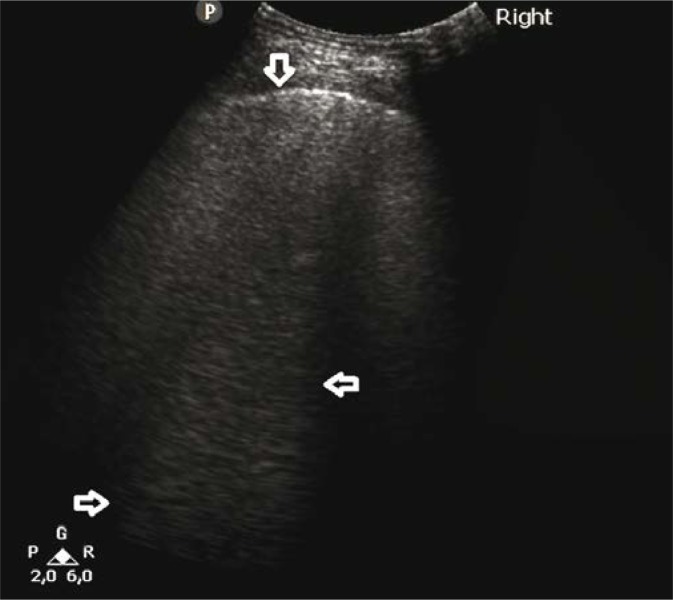

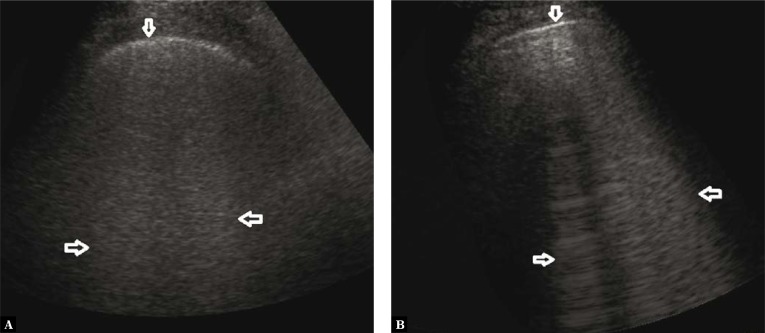

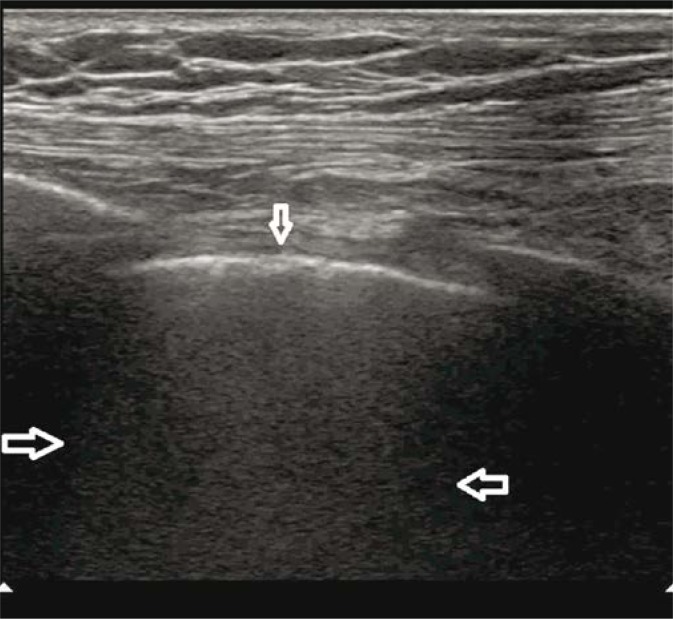

Fig. 1.

Numerous B-line artifacts (→←) forming a pattern corresponding to alveolar-interstitial syndrome; the pleural line with maintained continuity and echogenicity (↓). A convex probe

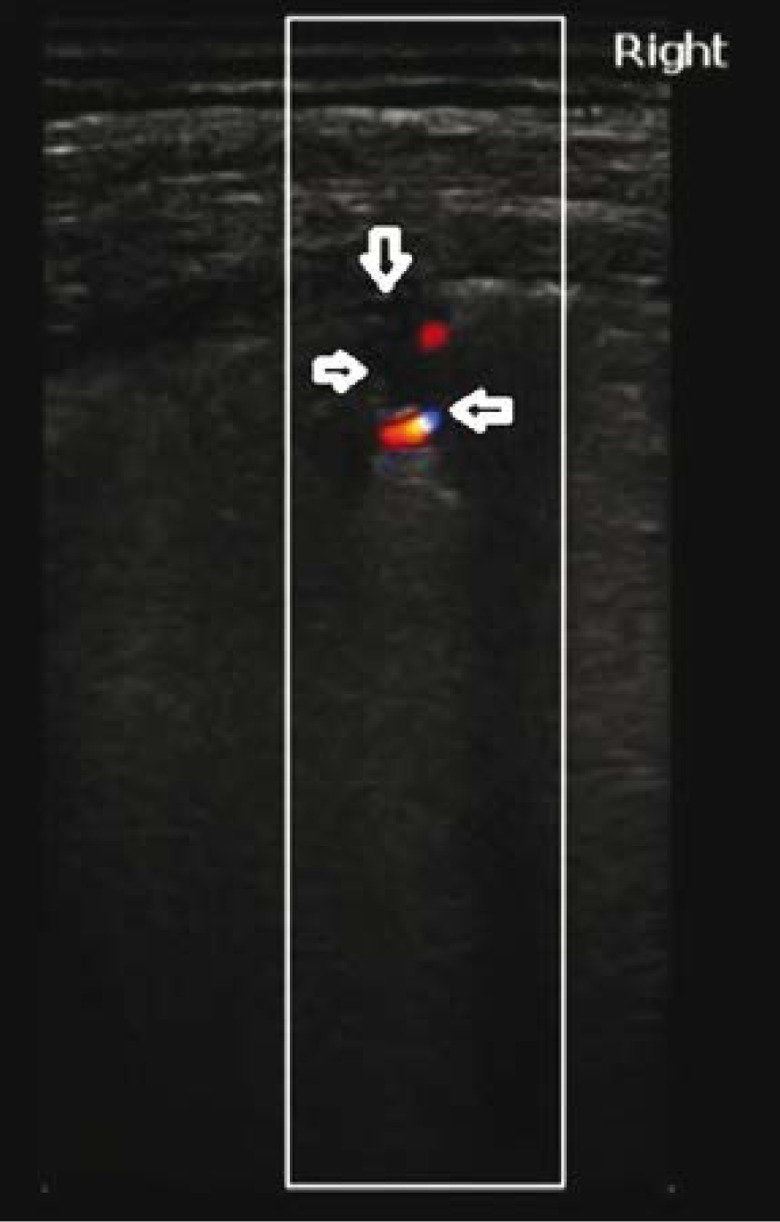

Fig. 2.

Pulmonary embolism. A wedge-shaped anechogenic subpleural consolidation (→) with a hypoechogenic pleural line and a trace volume of fluid directly above the consolidation (↓); vascular sign (←). A linear probe

Case 2

A 32-year-old patient with overlap syndrome (systemic lupus erythematosus/polymyosis) and anti-synthetase syndrome. Hospitalised due to exacerbation of the underlying disease and acute respiratory distress. LUS showed alterations typical of DAH (Fig. 3, Fig. 4), confirmed by HRCT and bronchoscopy.

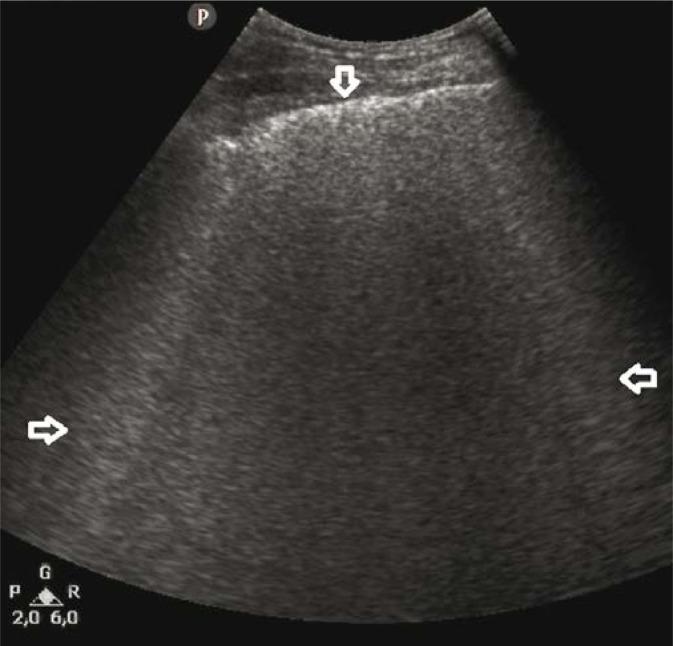

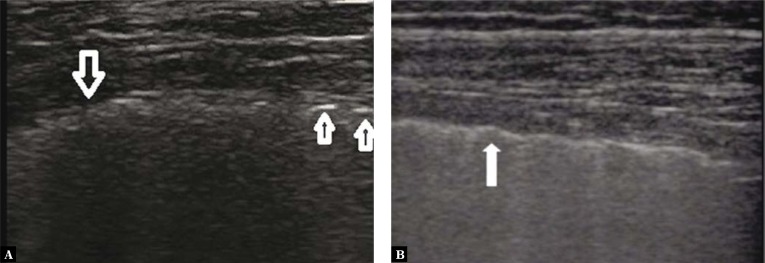

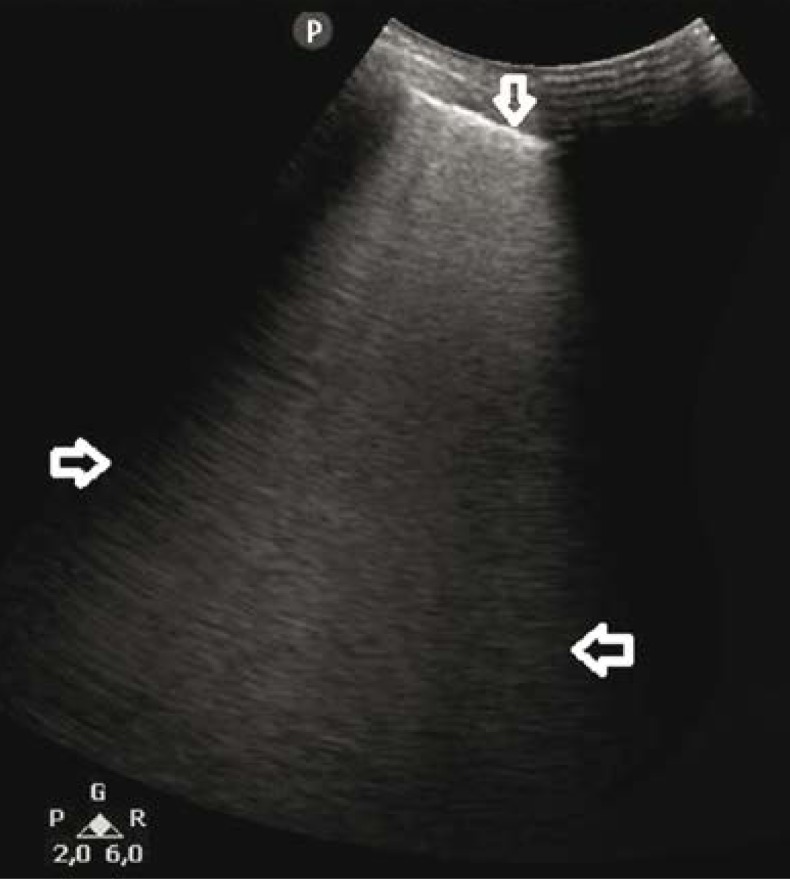

Fig. 3.

B-line artifacts forming patterns corresponding to alveolar-interstitial syndrome and the white lung sign (→←); a regionally irregular, hypoechogenic pleural line (↓). A convex probe

Fig. 4.

Diffuse alveolar haemorrhage (DAH). Three separate, conical hypoechogenic consolidations marked by homogeneous echogenicity, with a hypoechogenic pleural line (↓↑). The consolidations correspond to pulmonary lobules. A linear probe

Case 3

A 54-year-old patient with diagnosed systemic sclerosis and interstitial lung disease. Hospitalised due to dyspnoea, which was gradually exacerbating over the last few days (initially on exertion, and for the last few days at rest). The linear probe showed lesions typical for pulmonary fibrosis as well as changes in the course of active ILD (Fig. 5, Fig. 6). Lung lesions were confirmed by HRCT.

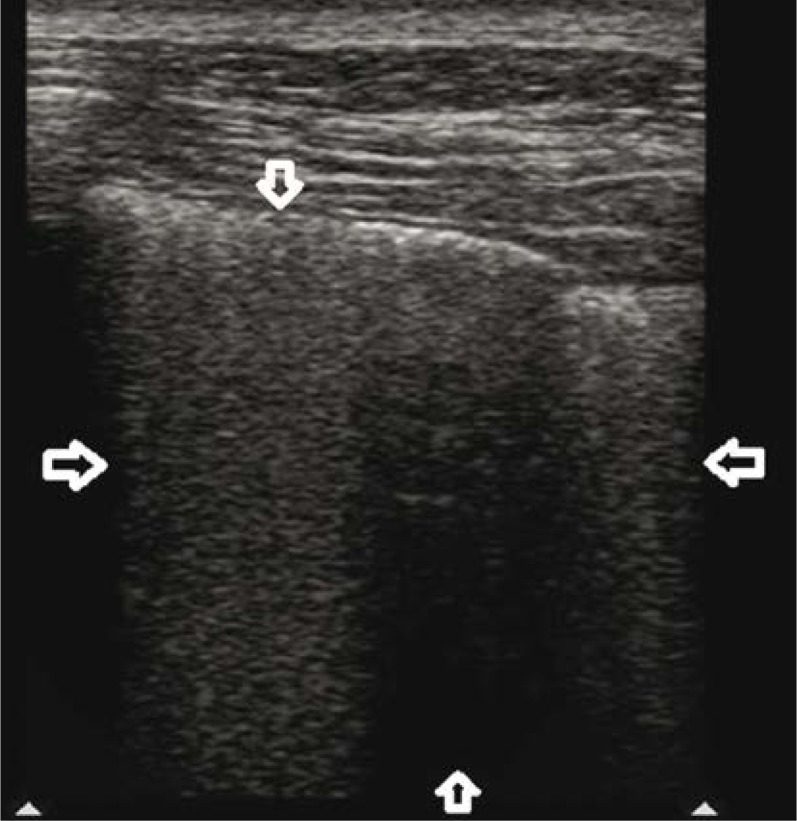

Fig. 5.

A. Interstitial lung disease (ILD) – pulmonary fibrosis; numerous B-line artifacts forming patterns corresponding to alveolar-interstitial syndromes and the white lung sign (→←) are visible in the lower fields of both lungs – the latter is seen regionally; an abnormal pleural line, blurred and with decreased echogenicity (↓); B. ILD – active lesions (alveolitis); alveolar-interstitial syndromes and the white lung sign arising from the echogenic pleural line. A convex probe

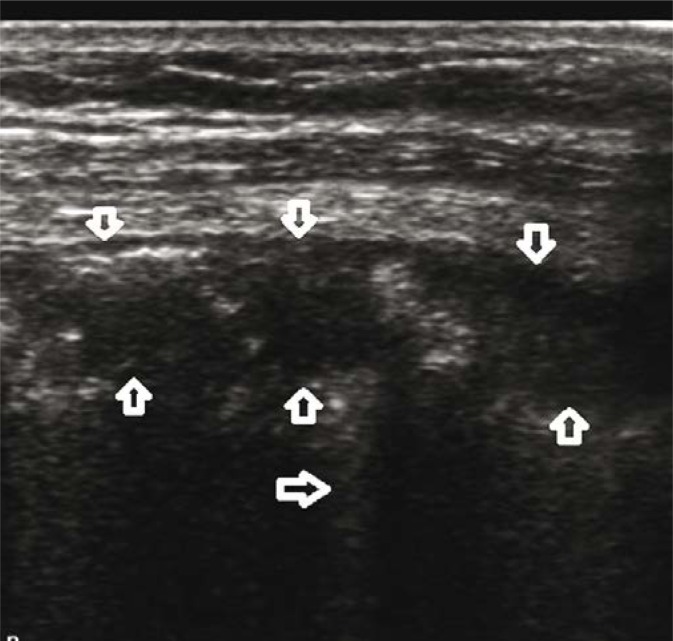

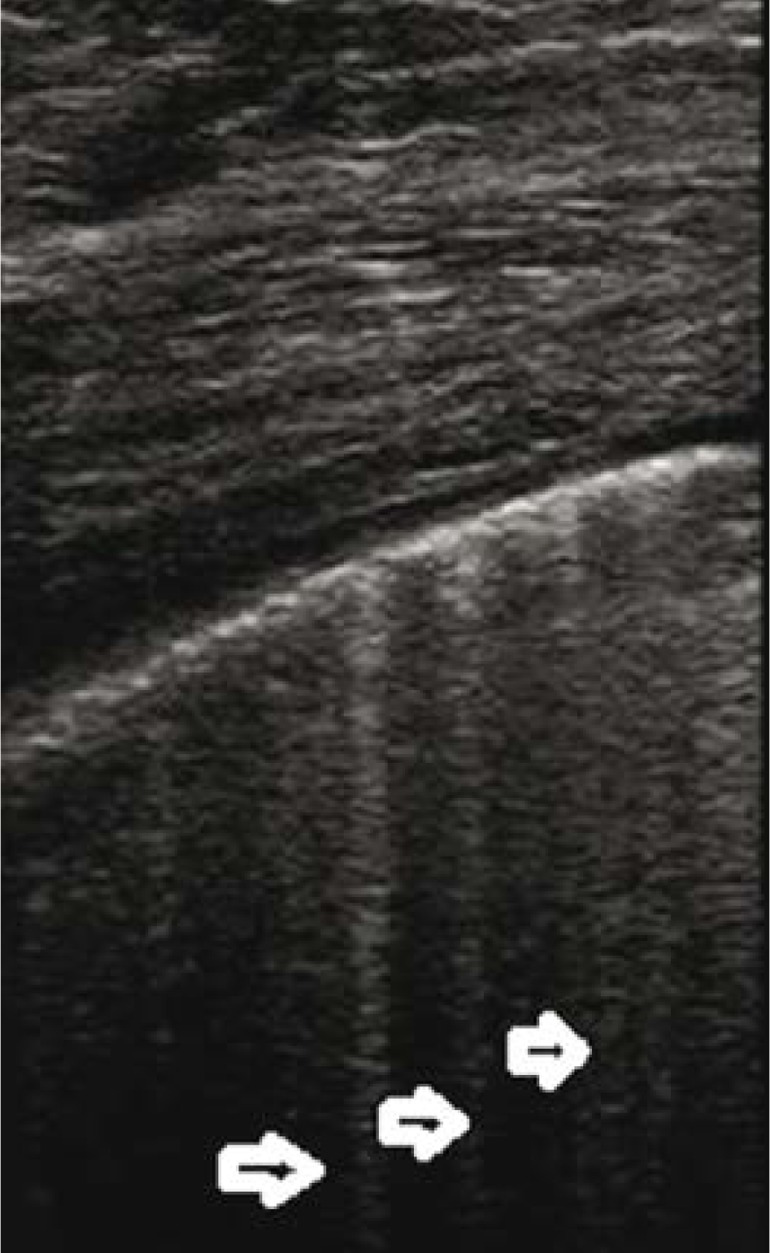

Fig. 6.

A. ILD – chronic (pulmonary fibrosis); a blurred, irregular, fragmented hypoechogenic pleural line; B. ILD – active lesions (alveolitis); an irregular pleural line with maintained continuity and echogenicity of its structure. A linear probe

Case 4

A 28-year-old patient with viral pneumonia; a positive H1N1 test. The patient presented with signs of lower respiratory tract infection and acute respiratory distress. Inflammation parameters in laboratory tests were high. LUS revealed features of non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema, which in conjunction with the clinical data suggested a viral infection of the respiratory tract (Fig. 7, Fig. 8). The diagnosis was confirmed by HRCT and a test for influenza.

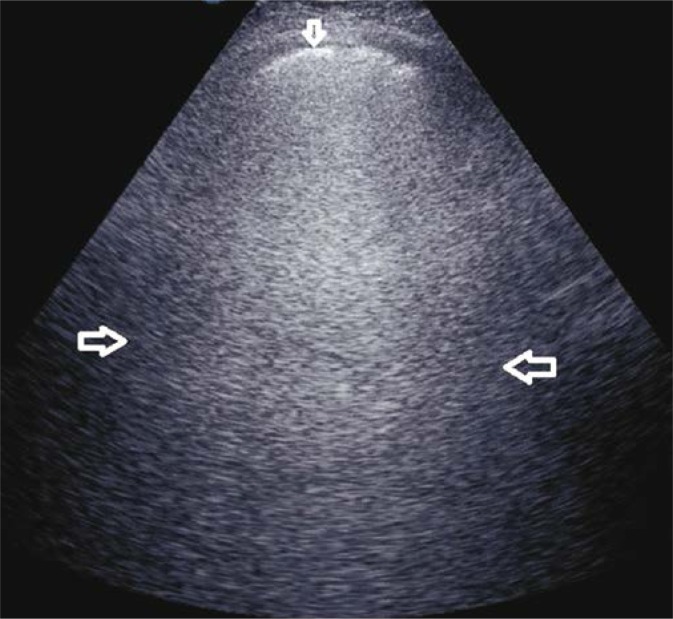

Fig. 7.

The white lung sign (←→) with regionally maintained normally aerated lung areas (spared areas) was seen in both lungs, above the entire anterior and lateral chest wall and in the lower fields above the posterior chest wall. A convex probe

Fig. 8.

Viral pneumonia. Unevenly distributed interstitial lesions in the lungs (←→), spared areas (↑) and small subpleural consolidations (↓). A linear probe

Case 5

An 89-year-old patient, bedridden for the past two years, with a history of two ischemic strokes. Hospitalised due to an infection of the urinary tract. Status post food aspiration. Percutaneous oxygen saturation decreased to 83%. The findings of a chest X-ray performed together with LUS within the first hour after aspiration were normal (Fig. 9, Fig. 10). As a result of oxygen therapy and metronidazole, complete regression of the lung lesions visible in LUS was achieved.

Fig. 9.

Aspiration pneumonia. The white lung sign is seen in the middle field of the right lung (←→); the pleural line with normal continuity and echogenicity (↓). A convex probe

Fig. 10.

Aspiration pneumonia (the first hour following a food aspiration episode). B-lines blend together to form the white lung sign, and they obscure A-line artifacts (→←); a normal pleural line (↓); A linear probe

Case 6

A 67-year-old patient with diagnosed chronic heart failure, coronary heart disease, and chronic atrial fibrillation, hospitalised due to dyspnoea at rest. Physical examination revealed a respiratory rate of 34 breaths/min, orthopnoea, crackling above the lower fields of both lungs, peripheral edema. The patient was diagnosed with cardiogenic pulmonary edema, confirmed with LUS and chest X-ray (Fig. 11, Fig. 12).

Fig. 11.

Cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. B-line artifacts forming patterns corresponding to interstitial and alveolar-interstitial syndromes (←→) symmetrically in the lower and middle fields of both lungs; a normal pleural line (↓). A convex probe

Fig. 12.

Cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. Numerous B-line artifacts (→) are seen bilaterally in the lower and middle fields; a normal pleural line. A linear probe

Discussion

In Case 1, examination with a convex probe only, and the multiple alveolar-interstitial syndromes found in both lungs would have led to a diagnosis of cardiogenic pulmonary edema. As a result, prompt treatment targeted at cardiogenic pulmonary oedema would have been initiated, with a change of the therapeutic decisions only taking place following treatment failure. In the case in question, the use of a linear probe allowed to identify the actual cause of the alveolar-interstitial syndromes. Imaging with a linear probe primarily showed,subpleural consolidations to exist, marked by sonomorphology typical for pulmonary embolism (small subpleural areas of pulmonary infarction)(7–8). At the same time, it allowed the correct identification of the vertical artifacts visible earlier, with most of them identified as C-lines when the linear probe was applied.

In Case 2, B-line artifacts, observed with the help of a convex probe, can be primarily seen. The examination continued with a linear probe apart from B-line artifacts also shows isolated subpleural consolidations, which are hypoechogenic, shallow, wedge- or boatshaped, and are accompanied by an air-trap sign and a C-line artifact. The evaluation of flow patterns was only possible with the use of the linear probe, due to the small size of the lesions. The vascularity pattern of the lesions (normal in some, and containing the vascular sign in others), the sonomorphology of the subpleural lesions assessed with the linear probe, and the patient’s clinical picture indicated DAH (further confirmed by bronchofiberoscopy and HRCT).

Case 3 describes a patient who reported gradually increasing breathing discomfort on exertion. From the clinical perspective, the patient displayed signs of systemic sclerosis (Raynaud’s phenomenon, painful joints, thinning of the lips, oedema of the palms and forearms). During conventional lung ultrasound examination performed with a convex probe, symmetrical patterns corresponding to alveolar-interstitial syndromes and the white lung sign were seen bilaterally in the lower and medium lung fields. This allowed to the conclusion that the problem concerned the pulmonary interstitium, and that an extensive process was involved, even though its origin remained unclear. The use of a linear probe revealed typical signs of pulmonary fibrosis in the lower fields of both lungs (an irregular, fragmented, and locally blurred pleural line), which, considering the entire clinical picture, is characteristic for interstitial lung disease related to systemic sclerosis(9,10). Additionally, the pleural line with maintained continuity (i.e. not damaged by fibrosis) was seen in the middle fields (where the white lung sign was discovered with the convex probe). This indicates active lesions suggestive of alveolitis(11).

Case 4 concerns a patient with acute respiratory distress. Even imaging with a convex probe revealed numerous B-line artifacts forming patterns corresponding to alveolar-interstitial syndromes and the white lung sign, as well as spared areas. Imaging with a linear probe showed small subpleural consolidations with a locally hypoechogenic pleural line. The application of LUS in the diagnostics of infectious interstitial pneumonia has been widely discussed in numerous publications(12–14). The clinical picture together with the lesions observed on LUS were suggestive of bilateral infectious interstitial pneumonia. A virus was the most probable etiological factor in this case.

The last two case reports do not raise any diagnostic doubts. In Case 5, the patient’s clinical picture as well as the description of the lesions seen in LUS are typical for cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. In the last case report, the characteristic patient history and the patient’s clinical condition suggest aspiration pneumonia. In both cases, the fact that the linear probe did not show any additional lesions in the sonomorphological picture confirmed the above clinical diagnoses.

Conclusions

Interstitial lesions in the form of B-line artifacts occur in diverse clinical conditions. In emergency departments and intensive care units, patients are initially evaluated with a convex probe. Under the protocol dedicated to patients with acute respiratory distress (the BLUE protocol), it is recommended that in emergency only micro-convex probe be used for the determination of the underlying causes of dyspnoea(15). The technique of LUS examination, in which low-frequency probes are used, produces different quantitative variants of B-line artifacts (interstitial syndromes, alveolar-interstitial syndromes, the white lung sign). Additionally, imaging with convex probes allows to determine the extent of the observed lesions.

The reported cases illustrate the benefits of using both convex and linear probes. Six different clinical conditions presenting with a very similar picture on convex probe imaging have been discussed. The differences in LUS are related to the lesions observed with a linear probe. Combining clinical data (patient history, physical examination, and other accessory examinations) with the findings of the LUS examination is essential. The evaluation of the lesions presenting as B-line artifacts requires the use of a linear probe facilitating additional information for the final diagnosis. A comprehensive (clinical and sonographic) diagnostic workup is the key to accurate diagnosis and prompt administration of appropriate treatment in a patient suffering from interstitial lung lesions.

Conflict of interest

The authors do not report any financial or personal connections with other persons or organizations, which might negatively affect the content of this publication and/or claim authorship rights to this publication.

References

- 1.Picano E, Frassi F, Agricola E, Gligorova S, Gargani L, Mottola G. Ultrasound lung comets: a clinically useful sign of extravascular lung water. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2006;19:356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lichtenstein DA, Mezière GA, Lagoueyte JF, Biderman P, Goldstein I, Gepner A. A-lines and B-lines: lung ultrasound as a bedside tool for predicting pulmonary artery occlusion pressure in the critically ill. Chest. 2009;136:1014–1020. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soldati G, Giunta V, Sher S, Melosi F, Dini C. “Synthetic” comets: a new look at lung sonography. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2011;37:1762–1770. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tardella M, Gutierrez M, Salaffi F, Carotti M, Ariani A, Bertolazzi C, et al. Ultrasound in the assessment of pulmonary fibrosis in connective tissue disorders: correlation with high-resolution computed tomography. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:1641–1647. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.120104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardinale L, Volpicelli G, Binello F, Garofalo G, Priola SM, Veltri A, et al. Clinical application of lung ultrasound in patients with acute dyspnea: differential diagnosis between cardiogenic and pulmonary causes. Radiol Med. 2009;114:1053–1064. doi: 10.1007/s11547-009-0451-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gargani L, Forfori F, Giunta F, Picano E. Lung ultrasound imaging of H1N1 influenza. Recenti Prog Med. 2012;103:23–25. doi: 10.1701/1022.11154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfeil A, Reissig A, Heyne JP, Wolf G, Kaiser WA, Kroegel C, et al. Transthoracic sonography in comparison to multislice computed tomography in detection of peripheral pulmonary embolism. Lung. 2010;188:43–50. doi: 10.1007/s00408-009-9195-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang L, Ma Y, Zhao C, Shen W, Feng X, Xu Y, et al. Role of transthoracic lung ultrasonography in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129909. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinal-Fernandez I, Pallisa-Nuñez E, Selva-O’Callaghan A, Castella-Fierro E, Simeon-Aznar CP, Fonollosa-Pla V, et al. Pleural irregularity, a new ultrasound sign for the study of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis and antisynthetase syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33(Suppl. 91):S136–S141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song G, Bae SC, Lee YH. Diagnostic accuracy of lung ultrasound for interstitial lung disease in patients with connective tissue diseases: a meta-analysis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buda N, Piskunowicz M, Porzezińska M, Kosiak W, Zdrojewski Z. Lung ultrasonography in the evaluation of interstitial lung disease in systemic connective tissue diseases: criteria and severity of pulmonary fibrosis – analysis of 52 patients. Ultraschall Med. 2016;37:379–385. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-110590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reissig A, Copetti R. Lung ultrasound in community-acquired pneumonia and in interstitial lung diseases. Respiration. 2014;87:179–189. doi: 10.1159/000357449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Volpicelli G, Frascisco MF. Sonographic detection of radio-occult interstitial lung involvement in measles pneumonitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:128.e1–128.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo Giudice V, Bruni A, Corcioni E, Corcioni B. Ultrasound in the evaluation of interstitial pneumonia. J Ultrasound. 2008;11:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jus.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lichtenstein DA, Mezière GA. Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure: the BLUE protocol. Chest. 2008;134:117–125. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]