Abstract

Background

The morbidity rate after pancreaticoduodenectomy remains high. The objectives of this retrospective cohort study were to clarify the risk factors associated with serious morbidity (Clavien–Dindo classification grades IV–V), and create complication risk calculators using the Japanese National Clinical Database.

Methods

Between 2011 and 2012, data from 17,564 patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy at 1,311 institutions in Japan were recorded in this database. The morbidity rate and associated risk factors were analyzed.

Results

The overall and serious morbidity rates were 41.6% and 4.5%, respectively. A pancreatic fistula (PF) with an International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) grade C was significantly associated with serious morbidity (P < 0.001). Twenty‐one variables were considered statistically significant predictors of serious complications, and 15 of them overlapped with those of a PF with ISGPF grade C. The predictors included age, sex, obesity, functional status, smoking status, the presence of a comorbidity, non‐pancreatic cancer, combined vascular resection, and several abnormal laboratory results. C‐indices of the risk models for serious morbidity and grade C PF were 0.708 and 0.700, respectively.

Conclusions

Preventing a PF grade C is important for decreasing the serious morbidity rate and these risk calculations contribute to adequate patient selection.

Keywords: Pancreaticoduodenectomy, Postoperative complications, Risk calculator

Introduction

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) remains the only curative option for patients with a malignant neoplasm arising from a periampullary lesion. Recent advances in surgical techniques, interventional radiology, and perioperative intensive care support has reduced the mortality rate associated with PD to less than 5% 1, 2. However, the morbidity rate after PD remains high (38–44%) 2, 3, 4; it has not improved over recent decades, and it is much higher than morbidity rates following other surgical procedures for gastroenterological cancer 5, 6, 7. Clinically, the most relevant postoperative complication of PD is a pancreatic fistula (PF), which is often associated with the development of life‐threatening intra‐abdominal complications such as abscesses, early or delayed hemorrhage, the need for a relaparotomy, and death. To reduce the potential for a PF to develop, many surgeons have proposed a variety of surgical techniques, including pancreaticogastrostomy as an alternative reconstructive method 8, the placement of a pancreatic duct stent 9, the early removal of a prophylactic drain 10, or the use of a somatostatin analogue (e.g. octreotide) 11. However, they cannot eliminate the possibility of a PF occurrence. Additionally, patients who experience one complication are at an increased risk for developing subsequent complications, which means a longer hospital stay and increased medical costs. These negative outcomes caused by postoperative complications demonstrate the importance of studying patients’ risk factors in an effort to gain insight into preventative strategies and early intervention.

Although a surprising decrease in the mortality rate to 1–2% following PD has been identified, the majority of their reports were based on single institution studies from specialized high‐volume centers 1, 2. Therefore, it may be impossible to replicate these outcomes at other institutions, and various biases should be considered when these outcomes are referred to individual institutions or patients. Recently, population‐based studies reported higher perioperative mortality rates of pancreatectomy ranging from 2.5% to 5.9% 12, 13, 14, and they provided a more generalized and accurate estimate of overall perioperative mortality rates. In Japan, a web‐based data system called the National Clinical Database (NCD) collected perioperative medical data and postoperative outcome data for approximately 1.2 million surgical cases annually from more than 3,500 Japanese hospitals 15, 16; we reported excellent 30‐day postoperative and in‐hospital mortality rates of PD in 1.2% and 2.8% of cases, respectively 17. To provide individual feedback for patients’ preoperative risk‐adjusted outcome, we developed a risk calculation for predicting the possibility of a postoperative complication prior to undergoing PD. The possibility of a PD complication occurring can be easily estimated by entering available patient medical variables that can be easily utilized, for example, age, sex, disease status, preoperative laboratory data, etc.

In the current study, we clarified the occurrence rate of a serious complication after PD and the risk factors associated with serious morbidity using nationwide cohort data. Moreover, we validated the risk calculation model for predicting the development of serious complications after PD.

Methods

The NCD system in Japan

The NCD is a nationwide project that operates in cooperation with the certification board of the Japan Surgical Society. This prospective and multi‐centre clinical registry was created to provide feedback on risk‐adjusted outcomes to hospitals and surgeons for quality improvement purposes. From 2011, data from more than 1.2 million surgical cases were collected annually from more than 3,500 hospitals. As described extensively elsewhere 5, 6, 7, the NCD collected reliable and validated data, including demographics, laboratory results, comorbidities, and postoperative outcomes, for patients undergoing a range of surgeries in Japan. Data definitions are standardized across all hospitals. Trained and audited data managers or surgeons at each individual hospital collected data using a web‐based data management system 16. From 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2012, the NCD reported on 17,564 patients who underwent a PD procedure at 1,311 institutions.

Pre‐ and intra‐operative variables

In this study, a set of potentially predictive variables associated with complications after PD, most of which were also defined in the American College of Surgeons‐National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS‐NSQIP) analysis 13, was constructed from the NCD. Patients’ demographic variables, including sex, age (<60, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, and >79 years old), body mass index (BMI), weight loss, smoking status (Brinkman index), alcohol status, and the administration of preoperative chemo‐ or radiotherapy, were considered. Patients’ preoperative physical status was evaluated by using the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification (I, normal healthy; II, mild systemic disease; III, severe systemic disease; IV or V, severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life or moribund) and activities of daily life (ADL; independent vs. partially or totally dependent). Pre‐existing comorbidities included the following: (1) heart disease, including angina, a myocardial infarction, a percutaneous cardiac intervention, congestive heart failure within 30 days preoperatively, or previous cardiac surgery; (2) respiratory disease, including the presence of respiratory distress symptom, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, current pneumonia, or preoperative ventilator dependence; (3) cerebrovascular disease history within 30 days preoperatively, including stroke with or without residual deficit, transient ischemic attack, hemiplegia, paraplegia, quadriplegia, or impaired sensation; (4) peripheral vascular disease, including revascularization for peripheral vascular disease, claudication, rest pain, amputation, or gangrene; (5) dialysis or acute renal failure; (6) hypertension; (7) diabetes that requires oral medication or is insulin dependent; (8) ascites; (9) blood clotting disorders without medical treatment; (10) sepsis; (11) a red blood cell transfusion preoperatively; (12) esophageal varices; and (13) chronic steroid use.

Indications for benign and malignant tumors were identified using the Union for International Cancer Control classification system. Concerning the PD procedure, emergency or planned surgery, lymph node dissection, combined vascular reconstruction, and other organ excisions were included as variables. However, the types of operative PD (e.g. subtotal stomach‐preserving PD, pylorus‐preserving PD, etc), texture of the remnant pancreas, and diameter of the pancreatic duct were excluded because those data were not collected in the system. Several laboratory values, including the hemoglobin level, white blood cell count, hematocrit level, platelet count, albumin level, bilirubin level, liver enzyme levels, urea nitrogen level, and international normalized ratio of prothrombin time (PT‐INR), were also included. Finally, about 60 pre‐ and intra‐operative variables were assessed to predict patients’ postoperative outcome or specific morbidity.

Postoperative outcome

The outcome measure of the present study was the occurrence rate of a serious complication or a PF after PD. Complications included surgical site infection (SSI), a PF, bile leakage, wound dehiscence, unplanned intubation, progressive renal insufficiency, urinary tract infection, deep venous thrombosis, a cerebrovascular accident or stroke, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation, a pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, ventilator dependence longer than 48 h, acute renal failure, bleeding complications defined by transfusions in excess of four units of blood, systematic sepsis, or systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). A Clavien–Dindo surgical complication classification (C–D) grade IV or V was considered a serious complication 18. The International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) scheme was used to classify a PF 19.

Risk calculator development

Data were randomly assigned into two subsets that were split 80/20: one for model development and the other for validation testing. There were no significant differences in the profiles of the variables between the model development and validation sets, according to univariate analysis using the Fisher's exact test and two‐tailed t‐test. In the development of the dataset, we built multivariable logistic regression models using a step‐wise selection of predictors with a P‐value for entry of 0.05 and for exit of 0.10. We assessed the models’ performance by applying them to the validation dataset and evaluating its ability to discriminate between the presence and absence of complications using the C‐index, which reflect the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for serious complications with C–D grades IV–V and a PF grade C. A ROC curve is a plot of a test's true positive rate (sensitivity) versus its false‐positive rate (1 ‐ specificity). Each point on the ROC curve indicates a pair of false‐ and true‐positive rates that is achieved using a particular threshold to dichotomize the predicted probabilities. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 21; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). This study was approved by the institutional review board of each institution.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

Between 2011 and 2012, data from 17,564 PD procedures conducted at 1,311 hospitals in Japan were collected and entered into the NCD (Table 1). This cohort included men (61.98%) and women (38.02%) with an average age of 68.46 years (Table S1). Concerning a pre‐existing comorbidity, hypertension (34.68%) and diabetes mellitus (28.06%) were the most frequently observed. Overall, 49.23% of patients were pathologically diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Among patients with non‐pancreatic cancer, the most common diseases were distal bile duct cancer (20.13%) and ampulla of Vater carcinoma (12.64%). The major laboratory data abnormalities were serum C‐reactive protein (CRP) level >1.0 mg/dl (18.07%), and total bilirubin level >2.0 mg/dl (22.27%). During the surgical procedure, combined vascular resection with PD was performed in 11.32% of the cohort.

Table 1.

Postoperative complications in the total pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) population of the National Clinical Database (NCD)

| Total cohort | |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 17,564 |

| Number of institutions | 1,311 |

| 30‐days mortality | 1.31% |

| In‐hospital mortality | 2.88% |

| Morbidity | 41.56% |

| Reoperation | 3.73% |

| Clavien–Dindo grades IV–V | 4.45% |

| SSI (superficial) | 7.87% |

| SSI (deep) | 3.56% |

| SSI (organ) | 13.55% |

| Pancreatic fistula gradea A/B/C | 22.22% |

| Pancreatic fistula gradea C | 4.83% |

| Bile leakage | 3.11% |

| Wound dehiscence | 2.12% |

| Pneumonia | 2.67% |

| Prolonged ventilation | 2.75% |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.21% |

| Cardiac occurrence | 0.85% |

| CNS complications | 0.91% |

| Acute renal failure | 1.02% |

| Urinary tract infection | 0.82% |

| Systemic sepsis | 5.40% |

| SIRS | 2.42% |

CNS central nervous system, SIRS systemic inflammatory response syndrome, SSI surgical site infection

According to the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) classification

Postoperative complication profile

The postoperative 30‐day and in‐hospital mortality rates were 1.31% and 2.88%, respectively (Table 1). The overall morbidity rate was 41.56%, and reoperation was performed in 3.73% of the cohort. The major complication after PD was PF and organ SSI in 22.22% and 13.55% of the cohort, respectively. This high occurrence of organ SSI was likely due to the development of a PF. Bile leakage, which is also a PD‐specific morbidity, occurred less frequently in 3.11% of the cohort.

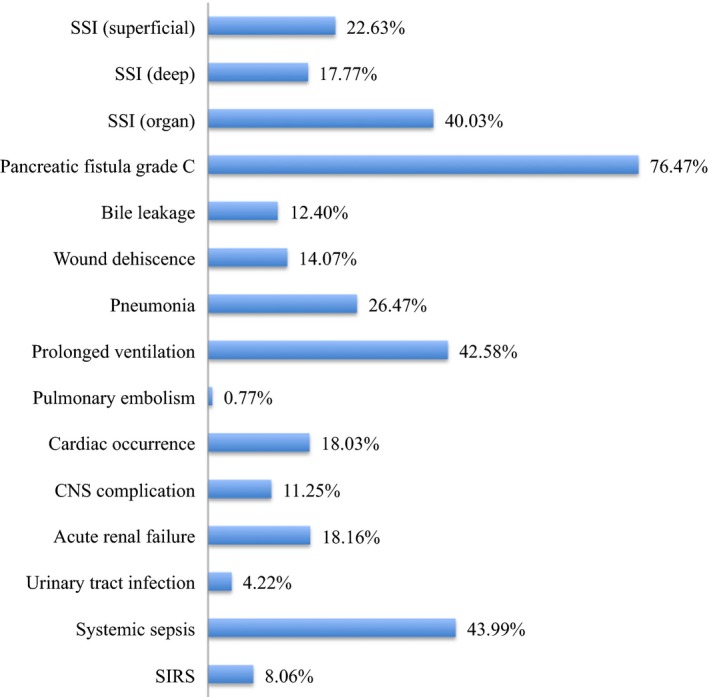

Serious complications with C–D grades IV–V and a PF grade C occurred in 4.45% and 4.83% of the cohort, respectively. The total of 70.5% in PF grade C was classified as C–D grades IV–V, whereas the remaining 29.5% were classified as C–D grades I–III. The development of a PF grade C was significantly associated with a serious complication (P < 0.001). A PF grade C was most commonly identified in 76.47% of cases with serious complications (Fig. 1). Although pneumonia, acute renal failure, central nervous system complications, cardiac occurrences, which were generally considered a systematic complication following gastroenterological surgery, occurred very rarely in the total cohort (2.67%, 1.02%, 0.91%, and 0.85%, respectively; Table 1), these conditions were associated with life‐threatening complications because of the high percentage of grades IV–V complications (26.47%, 18.16%, 11.25%, and 18.03%, respectively; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Overall postoperative complications of Clavien–Dindo grades IV–V. Among cases with a complication of grades IV–V after pancreaticoduodenectomy, a pancreatic fistula grade C and organ surgical site infection (SSI) were identified in 76.47% and 40.03% of patients, respectively. Pneumonia, central nervous system (CNS) complications, renal failure and cardiac occurrences, which were generally considered a systematic complication of gastroenterological surgery, were commonly observed in about 10–20% of patients. SIRS systemic inflammatory response syndrome, SSI surgical site infection

Risk profile associated with postoperative complications

We developed two different risk models for predicting postoperative complication of C–D grades IV–V and PF with an ISGPF grade C. All risk model data were derived from multivariable analysis (Tables 2, 3, S2 and S3). The following 15 variables were included in both models predicting C–D grades IV–V and PF with grade C as significant risk factors: male sex, high age, decreased daily activities, a BMI >25 kg/m2, an ASA class greater than III, a Brinkman index, a pre‐existing comorbidity of respiratory distress, a disease other than pancreatic cancer (e.g. distal bile duct carcinoma, gallbladder carcinoma, and duodenal carcinoma), combined vascular resection, a platelet count <80,000/μL, serum albumin level <2.5 g/dL, serum creatinine level >2.0 mg/dL, and CRP level >1.0 mg/dL. In contrast, a >10% weight loss, comorbidity of cerebrovascular disease and abnormal laboratory results (i.e. a white blood cell count >11,000 μL, PT‐INR >1.25, and serum sodium level >146 mEq/L) were identified as unique significant risk factors for the model predicting postoperative complications with C–D grades IV–V. Comorbidities of myocardial infarction, uncontrollable ascites, peripheral vascular disease and abnormal laboratory results (i.e. hemoglobin level <7 g/dL and hematocrit level >48% in men and hematocrit level >42% in women) were identified as unique significant risk factors for the model predicting PF with an ISGPF grade C.

Table 2.

Risk factors associated with serious postoperative complications with Clavien–Dindo grade IV or V

| Variables | β coefficient | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Male | 0.480 | 1.616 (1.329–1.964) | <0.001 |

| Age categorya | 0.192 | 1.211 (1.148–1.277) | <0.001 |

| BMI >25 kg/m2 | 0.610 | 1.841 (1.511–2.244) | <0.001 |

| ADL (partially or totally dependent) | 0.698 | 2.010 (1.469–2.750) | <0.001 |

| Weight loss >10% | 0.425 | 1.530 (1.166–2.007) | 0.002 |

| ASA (grade III/IV/V) | 0.403 | 1.496 (1.186–1.887) | 0.001 |

| Brinkman index >600 | 0.212 | 1.237 (1.018–1.503) | 0.033 |

| Preoperative comorbidities | |||

| Respiratory distress | 0.618 | 1.855 (1.147–3.002) | 0.012 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.456 | 1.577 (1.104–2.252) | 0.012 |

| Diseases | |||

| Distal bile duct carcinoma | 0.291 | 1.338 (1.102–1.625) | 0.003 |

| Gallbladder carcinoma | 0.638 | 1.893 (1.006–3.564) | 0.048 |

| Duodenal carcinoma | 0.564 | 1.758 (1.205–2.565) | 0.003 |

| Disseminated cancerb | 1.124 | 3.077 (1.451–6.524) | 0.003 |

| Operative procedure | |||

| Combined vascular resection | 0.384 | 1.468 (1.147–1.879) | 0.002 |

| Preoperative laboratory data | |||

| White blood cell >11,000/μL | 0.642 | 1.901 (1.263–2.862) | 0.002 |

| Platelet count <80,000/μL | 0.929 | 2.532 (1.192–5.377) | 0.016 |

| PT‐INR >1.25 | 0.409 | 1.505 (1.094–2.070) | 0.012 |

| Serum albumin level <2.5 g/dL | 0.783 | 2.189 (1.499–3.196) | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine level >2 mg/dL | 1.033 | 2.811 (1.775–4.450) | <0.001 |

| Serum sodium level >146 mEq/L | 0.954 | 2.596 (1.370–4.918) | 0.003 |

| Serum CRP level >1.0 mg/dL | 0.286 | 1.331 (1.098–1.615) | 0.004 |

| Intercept (β0) | –4.763 | <0.001 | |

ADL activities of daily living, ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification, BMI body mass index, CRP C‐reactive protein, PT‐INR prothrombin time/international normalized ratio

The variables of age were categorized into six groups, which is less than 60, 60 to 64, 65 to 69, 70 to 74, 75 to 79, and more than 80 years old. Therefore, this odds ratio indicated an alteration of relative risk in one unite increase in the age category

Pancreatic or other cancer with disseminated nodule

Table 3.

Risk factors associated with postoperative pancreatic fistula with ISGPF grade C

| Variables | β coefficient | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Male | 0.551 | 1.735 (1.431–2.104) | <0.001 |

| Age categorya | 0.184 | 1.202 (1.142–1.265) | <0.001 |

| BMI >25 kg/m2 | 0.588 | 1.800 (1.491–2.174) | <0.001 |

| ADL (partially or totally dependent) | 0.584 | 1.793 (1.309–2.456) | <0.001 |

| ASA (grade III/IV/V) | 0.422 | 1.525 (1.216–1.913) | <0.001 |

| Brinkman index >400 | 0.199 | 1.220 (1.020–1.460) | 0.029 |

| Preoperative comorbidities | |||

| Respiratory distress | 0.733 | 2.081 (1.309–3.308) | 0.002 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.964 | 2.621 (1.242–5.533) | 0.011 |

| Uncontrollable ascites | 0.820 | 2.271 (1.233–4.182) | 0.008 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.833 | 2.300 (1.052–5.028) | 0.037 |

| Diseases | |||

| Perihilar bile duct carcinoma | 0.844 | 2.326 (1.648–3.282) | <0.001 |

| Distal bile duct carcinoma | 0.554 | 1.740 (1.440–2.103) | <0.001 |

| Gallbladder carcinoma | 0.825 | 2.282 (1.289–4.041) | 0.005 |

| Ampulla of Vater carcinoma | 0.288 | 1.334 (1.047–1.700) | 0.020 |

| Duodenal carcinoma | 0.650 | 1.915 (1.324–2.770) | 0.001 |

| Operative procedure | |||

| Combined vascular resection | 0.306 | 1.358 (1.051–1.754) | 0.019 |

| Preoperative laboratory data | |||

| Haemoglobin level <7 g/dl | 0.972 | 2.643 (1.112–6.277) | 0.028 |

| Haematocrit >48% in male, >42% in female | 0.816 | 2.262 (1.394–3.671) | 0.001 |

| Platelet count <80,000/μL | 0.959 | 2.609 (1.277–5.329) | 0.008 |

| Serum albumin level <2.5 g/dL | 0.771 | 2.162 (1.481–3.157) | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine level >2 mg/dL | 0.736 | 2.089 (1.293–3.373) | 0.003 |

| Serum CRP level >1.0 mg/dL | 0.200 | 1.221 (1.012–1.473) | 0.037 |

| Intercept (β0) | –4.725 | <0.001 | |

ADL activities of daily living, ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification, BMI body mass index, CRP C‐reactive protein

The variables of age were categorized into six groups, which is less than 60, 60 to 64, 65 to 69, 70 to 74, 75 to 79, and more than 80 years old. Therefore, this odds ratio indicated an alteration of relative risk in one unite increase in the age category

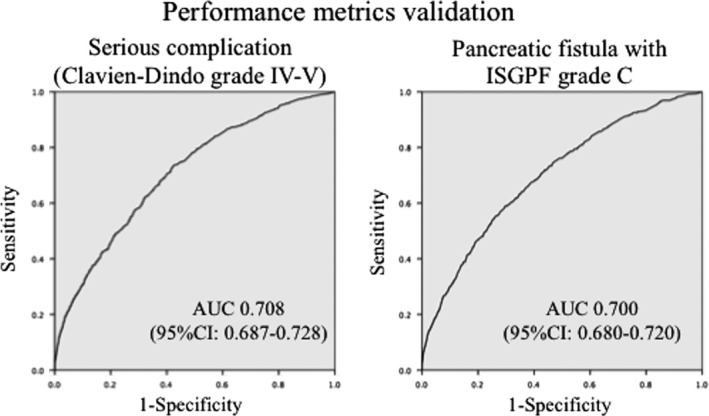

Model results and performance

Two different risk models were developed. The estimated coefficients, odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the variables included in the final logistic models are shown in Table 2 for serious postoperative complications with Clavien–Dindo grade IV or V and in Table 3 for pancreatic fistula with ISGPF grade C. We predicted the risk of each of the two outcomes for the patients in the testing cohort using the formula: Predicted mortality = e(β0 + ∑βiXi)/1 + e(β0 + ∑βiXi), where βi is the coefficient of the variable Xi in the logistic regression equation provided in the Tables. Xi = 1 if categorical risk factor is present and 0 if it is absent. We categorized age into six levels and included it as continuous variable. Therefore, Xi = 0 if the patient age is less than 60, Xi = 1 if 60–64, Xi = 2 if 65–69, Xi = 3 if 70–74, Xi = 4 if 75–79 and Xi = 5 for those above 79.

To evaluate model performance, the C‐index (a measure of model discrimination), which was the area under the ROC curve, was calculated for the validation sets (Fig. 2). The C‐indices of the model for complications with C–D grades IV–V and for PF with an ISGPF grade C were 0.708 (P < 0.006; CI: 0.687–0.728) and 0.700 (P < 0.001; CI: 0.680–0.720), respectively (ROC depicted in Fig. 2), indicating good discriminatory performance of the model.

Figure 2.

Validation of a risk calculator for Clavien–Dindo (C–D) grades IV–V complications and a pancreatic fistula (PF) with an International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) grade C. The C‐indices of the model for complications with C–D grades IV–V and for PF with an ISGPF grade C were 0.708 (P < 0.006; confidence interval (CI): 0.687–0.728) and 0.700 (P < 0.001; CI: 0.680–0.720), respectively, indicating good discriminatory performance of the model

Discussion

For the 17,564 patients undergoing PD recorded in the NCD, the 30‐day and in‐hospital mortality rates after PD were extremely low at 1.31% and 2.88%, respectively, which were much better than those of other national cohort‐based reports 12, 13, 14. However, morbidity was still high at 41.56%, and it was not excellent compared with that reported in other institutional or national reports 2, 3, 4, 13. A PF remained the leading cause of total complications; in particular, a PF with an ISGPF grade C was associated with 76.47% of all C–D grades IV–V complications and it significantly resulted in the occurrence of a serious morbidity. Therefore, preventing the occurrence of a PF with grade C is directly attributable to reducing serious complications and mortality after PD. In additional to a surgical technical modification for reducing PF 8, 9, 10, proper patient selection and individualized strategies before surgery are necessary to minimize serious complications associated with PD. Using our risk model for PD complications, we can obtain an accurate and individualized assessment of patients’ postoperative potential risk associated with the proposed procedures. This assessment is critical for judging whether surgical benefits sufficiently outweigh the risks for these potentially operable but high‐risk patients.

Recently, predictive models that calculate the postoperative mortality risk after PD have been developed in the United States using the ACS‐NSQIP database 13 or the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) 12. The NIS is an all‐payer database of hospital discharge data and it established a risk model for predicting perioperative mortality using nomogram analysis 20. However, this analysis has limitations, as it lacks important mortality‐relevant factors such as the ASA score, comorbidity information, and laboratory data. The ACS‐NSQIP database collects prospective multi‐centre clinical data for feedback of the outcomes to hospitals to improve surgical quality by establishing a risk calculator. Compared to the ACS‐NSQIP Pancreatectomy Risk Calculator, our NCD risk calculator is more specialized for PD and is likely to provide more precise estimations because the NCD includes more patients (17,564 vs. 4,621) over a shorter period of time (2 years vs. 3 years), and it has more detailed patient information and laboratory data (about 60 pre‐ and intra‐operative variables) for predicting the overall morbidity or a specialized complication.

Although clinically relevant PF (an ISGPF grade B or C) commonly occurs in about 20% of patients undergoing PD, the occurrence of a PF grade C is very rare 1, 2, 3, 4. The development of a PF grade C is often associated with intra‐abdominal bleeding and can lead to mortality. Twenty‐one variables were found to be independent risk factors for the development of a PF grade C after PD in our study (Table 3). Male sex, age, an increased BMI, smoking status, a low ADL level, a high ASA score, and low albumin level have already been widely accepted as patient‐related risk factors that predispose patients to a PF 21, 22, 23, 24, 25. On the other hand, we could not assess the contribution of the pancreatic remnant texture, which directly influences the incidence and severity of PF formation, because the data were not collected in the web‐based NCD system. Alternatively, the presence of non‐pancreatic cancer diseases such as ampullary, biliary, or neuroendocrine tumors were indicated as a risk factor, because these diseases clearly reflect the remnant pancreatic characteristics of soft pancreatic texture, a thin pancreatic body, and a non‐fibrotic pancreatic parenchyma, which greatly increases the risk of a PF. Moreover, the comorbidities of myocardial infarction and peripheral vascular disease were also demonstrated as significant factors of a PF grade C. In the previous report, coronary artery disease was identified as a risk of PF because arterial sclerosis decreased visceral perfusion, which leads to anastomotic ischemia 22, 26. Arterial sclerosis implies vascular fragility and it also may lead to PF grade C, because slight surgical damage to the vascular wall may cause an aneurysm to develop during the postoperative course.

The high CRP values were identified as independent risk factors of serious morbidity. The preoperatively elevated CRP value has been considered to reflect the presence of systematic inflammatory response (SIR), which largely contributes to the wasting of muscle and adipose tissue, i.e. cachexia 27. The presence of SIR has been shown to worsen anastomotic healing and infectious complications of patients with pancreatic cancer and other gastroenterological cancers 28.

Combined vascular resection in pancreatic cancer surgery is one way to improve resectability by obtaining cancer‐free surgical margins. At several high‐volume centers in Japan, combined resection has been performed in more than 40% of resected cases 29, 30, whereas the rate within this cohort was much lower at 11%. This may reflect the fact that the majority of locally advanced pancreatic cancer cases that were likely to require combined vascular resection were referred to high‐volume centers. Combined vessel resection demands a more difficult technique, intra‐operative blood loss and a long operation time 31, 32 and was considered a significant factor for lethal postoperative complications in this study. These potentially high‐risk operations must be performed at high‐volume centers.

We should also mention that approximately 20% of patients with grades IV–V complications were caused by non‐pancreatectomy‐specific complications such as pneumonia, central nervous system complications, cardiac occurrence, etc. Of course, every effort must be made to prevent a PF; however, other more general postoperative complications involving the cardiovascular and pulmonary systems are critically important and surgeons should target them for systematic quality improvement in the preoperative period. In the present cohort, 30.3% of patients were over 75 years (data not shown). A highly aggressive surgical procedure of PD predominantly afflicts the elderly, who are more likely to be infirm and suffer from multiple pre‐existing comorbidities. As the number of elderly patients with potentially multiple comorbidities increases, proper patient selection and individualized preoperative preparation is needed using an accurate estimation of the complication risk, because postoperative outcomes differ depending on the original and co‐existing disease status and systematic condition.

There were several limitations to this study. First, the hospital volume was not included as a variable. Although this cohort included many patients undergoing PDs in low‐volume centers, the mortality rate of the total cohort was excellent. If some PD were gathered in specific high‐volume centres, we could achieve more excellent postoperative outcomes with much lower mortality, because many previous reports demonstrated the improvement in patient outcomes for high‐volume centre 14. Second, the postpancreatectomy hemorrhage is most critical secondary complication of PF associated with mortality; however, detailed information or classification according to the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definitions 33 was not collected on this system. Predicting the life‐threatening hemorrhage derived from PF may be actually needed for pancreatic surgeons. Third, a calculation model for ISGPF grade B or C is also clinically demanded. However, a model for grade B or C did not indicate better discriminatory performance comparing that for grade C.

In conclusion, we clarified the independent risk factors associated with serious complications and a PF grade C using the NCD data that included 17,564 cases of PD. Preventing a PF grade C is likely to contribute to reducing serious morbidity after PD. Using these risk calculators for PD complications, a surgeon can obtain the individualized prediction on possible morbidity rate associated with the proposed procedures, and educate patients about appropriate expectations over their postoperative course.

Supporting information

Table S1. Key descriptive data of patients characteristics.

Table S2. Univariate analysis associated with Clavien‐Dindo grade IV‐V complication.

Table S3. Univariate analysis associated with PF grade C.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their deep gratitude to all surgeons who performed PDs and all staff who entered the patients’ data into the NCD in the 1,311 hospitals. They also thank the working members of the JSGS Database Committee. This study was supported by a research grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (M.G.).

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Shuichi Aoki, The Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Surgery, Tokyo, Japan; Hiroaki Miyata, Mitsukazu Gotoh, The National Clinical Database, Tokyo, Japan and The Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Surgery (JSGS) database committee, Tokyo, Japan; Fuyuhiko Motoi, The Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Surgery, Tokyo, Japan; Hiraku Kumamaru, The National Clinical Database, Tokyo, Japan and The Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Surgery (JSGS) database committee, Tokyo, Japan; Hiroyuki Konno, Go Wakabayashi, The Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Surgery (JSGS) database committee, Tokyo, Japan; Yoshihiro Kakeji, The National Clinical Database, Tokyo, Japan and The Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Surgery (JSGS) database committee, Tokyo, Japan; Masaki Mori, The Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Surgery, Tokyo, Japan; Yasuyuki Seto, The Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Surgery, Tokyo, Japan and The National Clinical Database, Tokyo, Japan; Michiaki Unno, The Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Surgery (JSGS) database committee, Tokyo, Japan.

The author's affiliations are listed in the Appendix.

References

- 1. Vin Y, Sima CS, Getrajdman GI, Brown KT, Covey A, Brennan MF, et al. Management and outcomes of postpancreatectomy fistula, leak, and abscess: results of 908 patients resected at a single institution between 2000 and 2005. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:490–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Arnold MA, Chang DC, Coleman J, et al. 1423 pancreaticoduodenectomies for pancreatic cancer: a single‐institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schmidt CM, Powell ES, Yiannoutsos CT, Howard TJ, Wiebke EA, Wiesenauer CA, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy: a 20‐year experience in 516 patients. Arch Surg. 2004;139:718–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Behrman SW, Rush BT, Dilawari RA. A modern analysis of morbidity after pancreatic resection. Am Surg. 2004;70:675–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Watanabe M, Miyata H, Gotoh M, Baba H, Kimura W, Tomita N, et al. Total gastrectomy risk model: data from 20,011 Japanese patients in a nationwide internet‐based database. Ann Surg. 2014;260:1034–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kobayashi H, Miyata H, Gotoh M, Baba H, Kimura W, Kitagawa Y, et al. Risk model for right hemicolectomy based on 19,070 Japanese patients in the National Clinical Database. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:1047–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Matsubara N, Miyata H, Gotoh M, Tomita N, Baba H, Kimura W, et al. Mortality after common rectal surgery in Japan: a study on low anterior resection from a newly established nationwide large‐scale clinical database. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:1075–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Waugh JM, Clagett OT. Resection of the duodenum and head of the pancreas for carcinoma; an analysis of thirty cases. Surgery. 1946;20:224–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Motoi F, Egawa S, Rikiyama T, Katayose Y, Unno M. Randomized clinical trial of external stent drainage of the pancreatic duct to reduce postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticojejunostomy. Br J Surg. 2012;99:524–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kawai M, Tani M, Terasawa H, Ina S, Hirono S, Nishioka R, et al. Early removal of prophylactic drains reduces the risk of intra‐abdominal infections in patients with pancreatic head resection: prospective study for 104 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2006;244:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pederzoli P, Bassi C, Falconi M, Camboni MG. Efficacy of octreotide in the prevention of complications of elective pancreatic surgery. Italian Study Group. Br J Surg. 1994;81:265–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McPhee JT, Hill JS, Whalen GF, Zayaruzny M, Litwin DE, Sullivan ME, et al. Perioperative mortality for pancreatectomy: a national perspective. Ann Surg. 2007;246:246–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Parikh P, Shiloach M, Cohen ME, Bilimoria KY, Ko CY, Hall BL, et al. Pancreatectomy risk calculator: an ACS‐NSQIP resource. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12:488–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Wilde RF, Besselink MG, van der Tweel I, de Hingh IH, van Eijck CH, Dejong CH, et al. Impact of nationwide centralization of pancreaticoduodenectomy on hospital mortality. Br J Surg. 2012;99:404–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Suzuki H, Gotoh M, Sugihara K, Kitagawa Y, Kimura W, Kondo S, et al. Nationwide survey and establishment of a clinical database for gastrointestinal surgery in Japan: targeting integration of a cancer registration system and improving the outcome of cancer treatment. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:226–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gotoh M, Miyata H, Hashimoto H, Wakabayashi G, Konno H, Miyakawa S, et al. National Clinical Database feedback implementation for quality improvement of cancer treatment in Japan: from good to great through transparency. Surg Today. 2016;46:38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kimura W, Miyata H, Gotoh M, Hirai I, Kenjo A, Kitagawa Y, et al. A pancreaticoduodenectomy risk model derived from 8575 cases from a national single‐race population (Japanese) using a web‐based data entry system: the 30‐day and in‐hospital mortality rates for pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2014;259:773–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. >Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Are C, Afuh C, Ravipati L, Sasson A, Ullrich F, Smith L. Preoperative nomogram to predict risk of perioperative mortality following pancreatic resections for malignancy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:2152–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gaujoux S, Cortes A, Couvelard A, Noullet S, Clavel L, Rebours V, et al. Fatty pancreas and increased body mass index are risk factors of pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery. 2010;148:15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lermite E, Pessaux P, Brehant O, Teyssedou C, Pelletier I, Etienne S, et al. Risk factors of pancreatic fistula and delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy with pancreaticogastrostomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:588–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Machado NO. Pancreatic fistula after pancreatectomy: definitions, risk factors, preventive measures, and management‐review. Int J Surg Oncol. 2012;2012:602478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Taflampas P, Christodoulakis M, Tsiftsis DD. Anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection for rectal cancer: facts, obscurity, and fiction. Surg Today. 2009;39:183–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Winter JM, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Alao B, Lillemoe KD, Campbell KA, et al. Biochemical markers predict morbidity and mortality after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1029–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lin JW, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Riall TS, Lillemoe KD. Risk factors and outcomes in postpancreaticoduodenectomy pancreaticocutaneous fistula. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:951–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mueller TC, Burmeister MA, Bachmann J, Martignoni ME. Cachexia and pancreatic cancer: are there treatment options? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9361–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moyes LH, Leitch EF, McKee RF, Anderson JH, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. Preoperative systemic inflammation predicts postoperative infectious complications in patients undergoing curative resection for colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1236–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nakagohri T, Kinoshita T, Konishi M, Inoue K, Takahashi S. Survival benefits of portal vein resection for pancreatic cancer. Am J Surg. 2003;186:149–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yoshitomi H, Kato A, Shimizu H, Ohtsuka M, Furukawa K, Takayashiki T, et al. Tips and tricks of surgical technique for pancreatic cancer: portal vein resection and reconstruction (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:E69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen JY, Feng J, Wang XQ, Cai SW, Dong JH, Chen YL. Risk scoring system and predictor for clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5926–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yeh TS, Jan YY, Jeng LB, Hwang TL, Wang CS, Chen SC, et al. Pancreaticojejunal anastomotic leak after pancreaticoduodenectomy–multivariate analysis of perioperative risk factors. J Surg Res. 1997;67:119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery. 2007;142:20–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Key descriptive data of patients characteristics.

Table S2. Univariate analysis associated with Clavien‐Dindo grade IV‐V complication.

Table S3. Univariate analysis associated with PF grade C.