Abstract

In the Belatacept Evaluation of Nephroprotection and Efficacy as First‐Line Immunosuppression Trial–Extended Criteria Donors (BENEFIT‐EXT), extended criteria donor kidney recipients were randomized to receive belatacept‐based (more intense [MI] or less intense [LI]) or cyclosporine‐based immunosuppression. In prior analyses, belatacept was associated with significantly better renal function compared with cyclosporine. In this prospective analysis of the intent‐to‐treat population, efficacy and safety were compared across regimens at 7 years after transplant. Overall, 128 of 184 belatacept MI–treated, 138 of 175 belatacept LI–treated and 108 of 184 cyclosporine‐treated patients contributed data to these analyses. Hazard ratios (HRs) comparing time to death or graft loss were 0.915 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.625–1.339; p = 0.65) for belatacept MI versus cyclosporine and 0.927 (95% CI 0.634–1.356; p = 0.70) for belatacept LI versus cyclosporine. Mean estimated GFR (eGFR) plus or minus standard error at 7 years was 53.9 ± 1.9, 54.2 ± 1.9, and 35.3 ± 2.0 mL/min per 1.73 m2 for belatacept MI, belatacept LI and cyclosporine, respectively (p < 0.001 for overall treatment effect). HRs comparing freedom from death, graft loss or eGFR <20 mL/min per 1.73 m2 were 0.754 (95% CI 0.536–1.061; p = 0.10) for belatacept MI versus cyclosporine and 0.706 (95% CI 0.499–0.998; p = 0.05) for belatacept LI versus cyclosporine. Acute rejection rates and safety profiles of belatacept‐ and cyclosporine‐based treatment were similar. De novo donor‐specific antibody incidence was lower for belatacept (p ≤ 0.0001). Relative to cyclosporine, belatacept was associated with similar death and graft loss and improved renal function at 7 years after transplant and had a safety profile consistent with previous reports.

Keywords: clinical research/practice, kidney transplantation/nephrology, clinical trial, donors and donation: deceased, donors and donation: extended criteria, donors and donation: donation after circulatory death (DCD), immunosuppressant, fusion proteins and monoclonal antibodies: belatacept

Short abstract

In patients transplanted with an extended donation criteria kidney, belatacept‐based immunosuppression is associated with a similar death/graft loss and improved renal function at 7 years posttransplant as a cyclosporine‐based immunosuppression, with a safety profile consistent with previous reports.

Abbreviations

- AE

adverse event

- CI

confidence interval

- CsA

cyclosporine

- DSA

donor‐specific antibody

- EBV

Epstein–Barr virus

- ECD

expanded criteria donor

- eGFR

estimated GFR

- HR

hazard ratio

- KDPI

Kidney Donor Profile Index

- LI

less intense

- MI

more intense

- PTLD

posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder

- q2w

every 2 weeks

- q4w

every 4 weeks

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

Introduction

The disparity between the number of patients awaiting kidney transplantation and the number of available donor kidneys continues to increase 1, 2. To address this growing demand, expanded criteria donor (ECD) kidneys are increasingly being used 2, 3; however, compared with recipients of non‐ECD kidneys, those who receive ECD kidneys are at increased risk of graft failure and cardiovascular events and have worse renal function and decreased life expectancy 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. Causes of graft lost include inherited donor lesions 11, the adverse effects of immunosuppression and antibody‐mediated chronic rejection. The calcineurin inhibitors cyclosporine (CsA) and tacrolimus—the existing standard of care for maintenance immunosuppression—are potentially nephrotoxic, which may contribute to declining renal function, the development of chronic allograft nephropathy and graft loss 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18. Because ECD kidneys may be more susceptible to the nephrotoxic effects of calcineurin inhibitors, the use of CsA or tacrolimus is of greater concern in recipients of ECD versus non‐ECD kidneys 19. The de novo development of donor‐specific antibodies (DSAs) and patient nonadherence to prescribed immunosuppressive regimens have also been recognized as major risk factors for graft loss 20, 21.

Belatacept is a soluble fusion protein composed of a modified version of the extracellular domain of cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 linked to the Fc domain of a human IgG1 antibody 22. Belatacept selectively inhibits T cell activation through costimulation blockade 23, 24, 25, 26, 27. In 2011, belatacept was approved in the United States and the European Union based in part on 3‐year data from two phase III trials: Belatacept Evaluation of Nephroprotection and Efficacy as First‐Line Immunosuppression Trial (BENEFIT) and BENEFIT–Extended Criteria Donors (BENEFIT‐EXT). These randomized phase III studies compared two belatacept‐based immunosuppressive regimens (more intense [MI] and less intense [LI]) with CsA‐based immunosuppression in adult kidney transplant recipients. In BENEFIT‐EXT, analyses performed at 1, 3 and 5 years after transplant demonstrated that belatacept‐based immunosuppression was associated with similar rates of patient and graft survival and superior renal function versus CsA‐based immunosuppression; however, rates of acute rejection were numerically higher with belatacept‐based treatment 28, 29, 30.

This report summarizes efficacy and safety outcomes from randomization to year 7 (month 84) in the intent‐to‐treat population of BENEFIT‐EXT.

Methods

Study design

The study design of BENEFIT‐EXT (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00114777) has been described 28. Briefly, this was a 3‐year, international, multicenter, randomized, partially blinded, active‐controlled, parallel‐group study of adults transplanted with an extended criteria donor kidney. Extended criteria donor kidneys were protocol defined as those from donors aged ≥60 years, from donors aged 50–59 years with at least two other risk factors (death due to cerebrovascular accident, history of hypertension, or terminal serum creatinine level >1.5 mg/dL), from donors with an anticipated cold ischemia time ≥24 h, or from non–heart‐beating donors (i.e. donation after cardiac death). Patients were randomized (1:1:1) to receive primary immunosuppression with a belatacept MI–based, belatacept LI–based or CsA‐based regimen. All patients received basiliximab induction, mycophenolate mofetil and corticosteroids.

BENEFIT‐EXT was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional review board or ethics committee at each site approved the protocol, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Outcomes

Efficacy and safety outcomes from randomization to month 84 (year 7), including time to death and/or graft loss, acute rejection, renal function, safety and de novo DSA incidence, are summarized. As in prior analyses 28, 29, 30, acute rejection was defined as central biopsy–proven rejection that was either clinically suspected for protocol‐defined reasons or clinically suspected for other reasons and treated. A combined end point comprising time to first occurrence of death, graft loss or estimated GFR (eGFR) <20 mL/min per 1.73 m2 was examined post hoc. GFR was estimated using the six‐variable MDRD equation 31. Adverse events (AEs) were mapped to terms from the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 17.0 (MedDRA MSSO, McLean, VA) and expressed as incidence rates adjusted per 100 person‐years of exposure to assigned treatment. Serious AEs are defined in the supplementary material. De novo DSA development was assessed centrally by solid‐phase flow cytometry (FLowPRA; One Lambda, Inc., Canoga Park, CA), with HLA class specificity (class I or II) determined by LABScreen single antigen beads (One Lambda, Inc.).

Statistical methods

For this prospective analysis, time to death or graft loss was compared between each belatacept‐based regimen and the CsA‐based regimen using a log‐rank test. Data are presented using Kaplan–Meier curves and event rates. Cox regression was used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the first 60 and 84 mo. Time to death and time to death‐censored graft loss were assessed as sensitivity analyses to understand the contribution of each individual component to the composite end point of time to death or graft loss; the same statistical methods were used as for the composite analysis, and no adjustment for multiplicity was made. See the supplementary material for censoring rules.

Mean eGFR and corresponding CIs were determined from months 1–84 using a repeated‐measures model with an unstructured covariance matrix. This model takes into account between‐subject variability and the intrasubject correlation between eGFR measurements across all time points and assumes that missing data are missing at random. The model included treatment, time and a time–treatment interaction; no further adjustment was made for other potentially confounding covariates. Time was regarded as a categorical variable (intervals of 3 mo up to month 36 and intervals of 6 mo thereafter). A sensitivity analysis was performed in which GFR values that were missing due to death or graft loss were imputed as zero. For this sensitivity analysis, the same model was used as for the primary analysis, but a Toeplitz covariance matrix best fit the data because the unstructured covariance matrix was not converging.

A slope‐based model without imputation was also used to determine whether there was a difference between each of the belatacept slopes and the CsA slope, assuming linearity of the eGFR values between months 1 and 84. The difference between slopes was tested using contrasts. Time was regarded as a continuous variable, treatment as a fixed effect, and intercept and time as random effects; no further adjustment was made for other potentially confounding covariates. A sensitivity analysis was performed in which GFR values that were missing due to death or graft loss were imputed as zero; the same model was used as for the slope analysis without imputation.

The statistical approaches used in this 7‐year analysis differ from those used at 1, 3, and 5 years after transplant 28, 29, 30. First, in the present report, all evaluable patients were analyzed per the intent‐to‐treat principle; evaluable patients were alive and observable at 84 mo after randomization or died or experienced graft loss by month 84. Similarly, the intent‐to‐treat population was analyzed at 1 and 3 years after transplant 28, 29, whereas a subgroup of patients corresponding to the long‐term extension cohort was analyzed at 5 years after transplant 30. The long‐term extension cohort represented a subset of the intent‐to‐treat population because it was composed of only those patients who completed 36 mo of study treatment and consented to continue the study beyond month 36 30. Second, rates of death and/or graft loss were presented as point estimates at 1 and 3 years after transplant 28, 29, but in the present analysis, the Kaplan–Meier method was used to derive estimated rates of death and/or graft loss. Third, renal function was assessed at 1, 3, and 5 years after transplant using analysis of variance, linear mixed modeling and analysis of covariance, respectively 28, 29, 30. At 7 years after transplant, renal function was examined using a repeated‐measures model. The statistical approaches used evolved to reflect convention at the time of analysis. Compared with earlier time points, the methods used in the present report are more statistically robust.

Results

Patient disposition

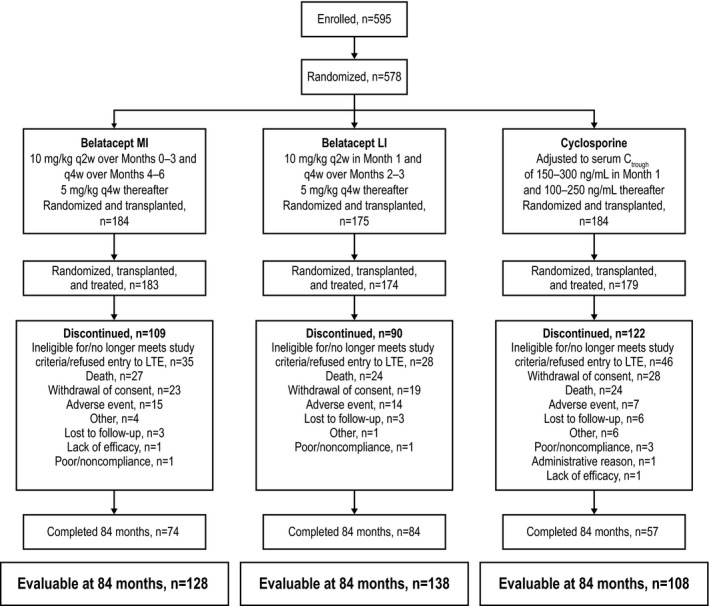

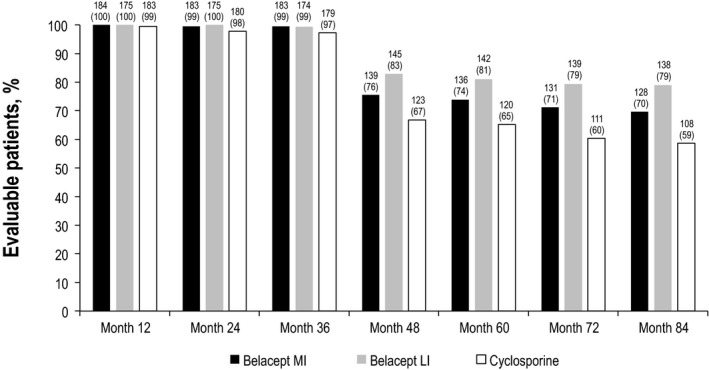

In total, 543 patients composed the intent‐to‐treat population; of these, 128 of 184 belatacept MI–treated, 138 of 175 belatacept LI–treated and 108 of 184 CsA‐treated patients had data available for the analysis at month 84 (Figure 1). At month 84, 68.9% of all randomized and transplanted patients were assessed for death or graft loss (Figure 2). Notably, only a small number of patients declined to participate in the long‐term extension (belatacept MI, n = 3; belatacept LI, n = 0; CsA, n = 8). The median duration of follow‐up for patients randomized to belatacept MI, belatacept LI and CsA was 84.0 mo (range 0.03–84.0 mo), 84.0 mo (range 0.03–84.0 mo) and 70.8 mo (range 0.03–84.0 mo), respectively (Table S1).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition. Evaluable patients were defined as those who were followed for >84 mo or who had died or experienced graft loss by month 84. LI, less intense; MI, more intense. q2w, every 2 weeks; q4w, every 4 weeks.

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients assessed for death or graft loss. Data values are number (percentage). LI, less intense; MI, more intense.

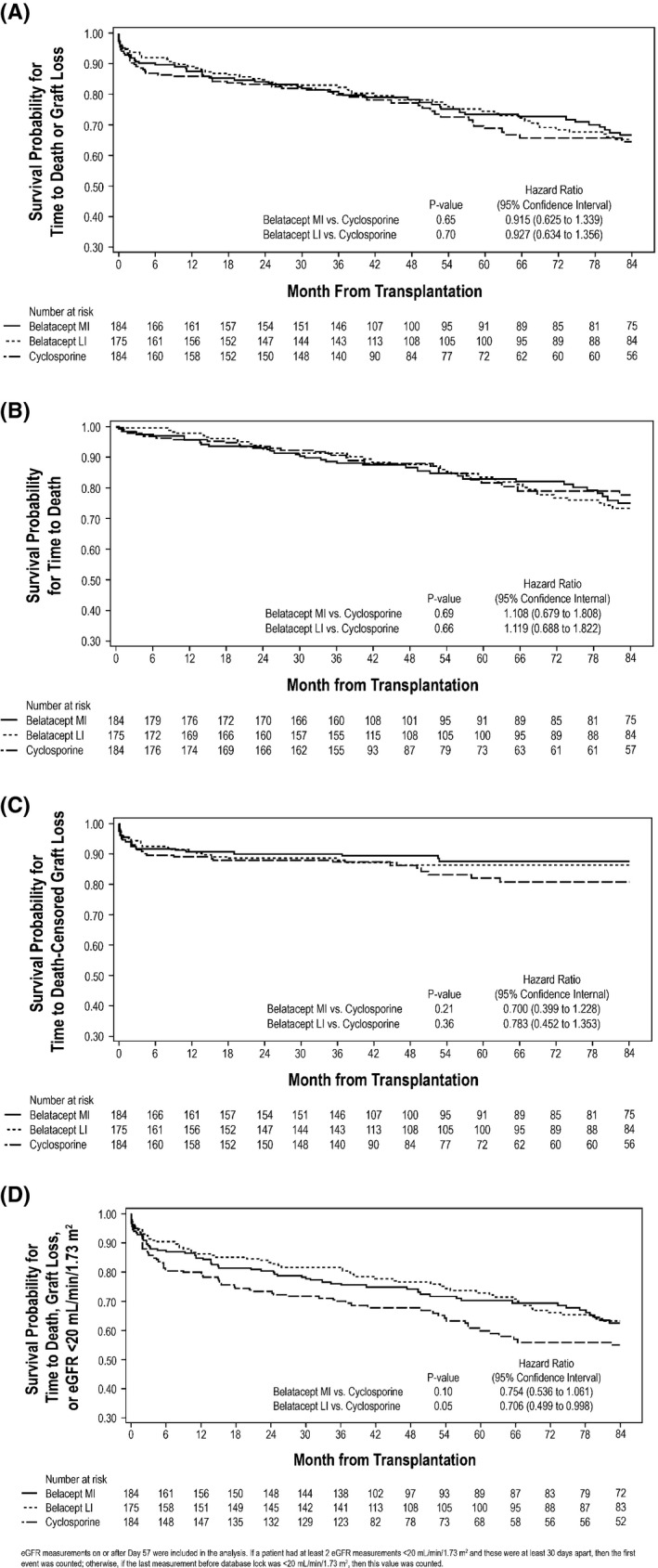

Patient and graft survival

Kaplan–Meier estimated rates of death or graft loss for belatacept MI, belatacept LI and CsA were 19.0%, 17.1%, and 20.2%, respectively, at month 36; 26.5%, 25.6%, and 31.2%, respectively, at month 60; and 33.4%, 34.7%, and 35.5%, respectively, at month 84 (Table S2). At month 60, the HR for the comparison of belatacept MI with CsA was 0.874 (95% CI 0.583–1.310; p = 0.51), and the HR for the comparison of belatacept LI with CsA was 0.822 (95% CI 0.544–1.242; p = 0.35). At month 84, the HR for the comparison of belatacept MI with CsA was 0.915 (95% CI 0.625–1.339; p = 0.65), and the HR for the comparison of belatacept LI with CsA was 0.927 (95% CI 0.634–1.356; p = 0.70) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curve for (A) the composite end point of time to death or graft loss; (B) the individual contribution of death; (C) the individual contribution of death‐censored graft loss; and (D) the combined end point of first occurrence of death, graft loss or eGFR <20 mL/min per 1.73 m 2 . eGFR, estimated GFR; LI, less intense; MI, more intense.

Kaplan–Meier estimated rates of death for belatacept MI, belatacept LI and CsA were 11.4%, 8.7%, and 9.5%, respectively, at month 36; 17.2%, 16.5%, and 18.5%, respectively, at month 60; and 24.9%, 26.7%, and 22.4%, respectively, at month 84 (Table S3). At month 60, the HR for the comparison of belatacept MI with CsA was 1.014 (95% CI 0.594–1.729; p = 0.95), and the HR for the comparison of belatacept LI with CsA was 0.907 (95% CI 0.523–1.571; p = 0.73). At month 84, the HR for the comparison of belatacept MI with CsA was 1.108 (95% CI 0.679–1.808; p = 0.69), and the HR for the comparison of belatacept LI with CsA was 1.119 (95% CI 0.688–1.822; p = 0.66) (Figure 3B). Causes of death are summarized in Table S4.

Kaplan–Meier estimated rates of death‐censored graft loss for belatacept MI, belatacept LI and CsA were 9.9%, 11.5%, and 12.8%, respectively, at month 36; 12.4%, 13.6%, and 18.0%, respectively, at month 60; and 12.4%, 13.6%, and 19.3%, respectively, at month 84 (Table S5). At month 60, the HR for the comparison of belatacept MI with CsA was 0.728 (95% CI 0.413–1.282; p = 0.27); the corresponding value for the comparison of belatacept LI with CsA was 0.815 (95% CI 0.469–1.415; p = 0.45). At month 84, the HR for the comparison of belatacept MI with CsA was 0.700 (95% CI 0.399–1.228; p = 0.21); the corresponding value for the comparison of belatacept LI with CsA was 0.783 (95% CI 0.452–1.353; p = 0.36) (Figure 3C). Causes of graft loss are summarized in Table S6.

Kaplan–Meier estimated rates for the combined end point (first occurrence of death, graft loss or eGFR <20 mL/min per 1.73 m2) for belatacept MI, belatacept LI and CsA were 23.9%, 18.3%, and 30.0%, respectively, at month 36; 29.8%, 27.1%, and 40.2%, respectively, at month 60; and 37.4%, 36.8%, and 45.1%, respectively, at month 84. HRs comparing freedom from death, graft loss or eGFR <20 mL/min per 1.73 m2 from randomization to month 84 were 0.754 (95% CI 0.536–1.061; p = 0.10) for belatacept MI versus CsA and 0.706 (95% CI 0.499–0.998; p = 0.05) for belatacept LI versus CsA (Figure 3D).

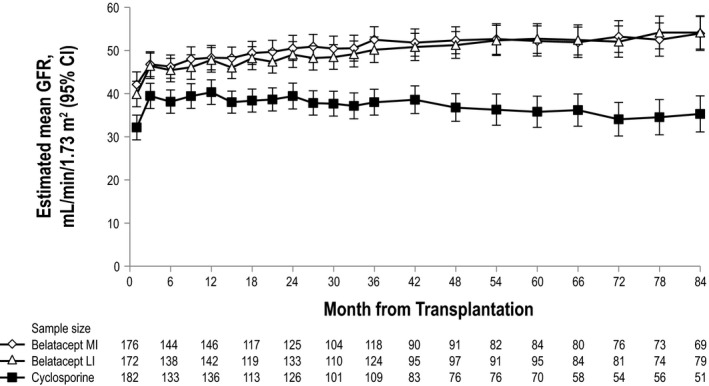

Renal function

From randomization to year 7, mean eGFR increased for both belatacept regimens but declined for CsA (Figure 4). Mean eGFR plus or minus standard error for belatacept MI at months 12, 36, 60, and 84 was 48.3 ± 1.3, 52.5 ± 1.4, 52.2 ± 1.7, and 53.9 ± 1.9 mL/min per 1.73 m2, respectively. The corresponding values for belatacept LI were 47.8 ± 1.3, 50.1 ± 1.4, 52.7 ± 1.6, and 54.2 ± 1.9 mL/min per 1.73 m2, whereas those for CsA were 40.3 ± 1.3, 38.0 ± 1.4, 35.8 ± 1.7, and 35.3 ± 2.0 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The estimated differences in GFR significantly favored each belatacept‐based regimen versus the CsA‐based regimen (p < 0.001 for overall treatment effect). Per the slope‐based model (and relative to month 1), patients randomized to belatacept MI or LI experienced a mean eGFR gain of 1.45 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI 0.94–1.96) and 1.51 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI 1.02–2.01) per year, respectively. Over the period from months 1 to 84, patients randomized to CsA had a mean decline in eGFR equivalent to −0.01 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI −0.55 to 0.52) per year. The GFR slopes diverged significantly between belatacept and CsA over time. The interaction of the treatment versus time effect deriving from the mixed‐effects model significantly favored each belatacept regimen versus CsA (each p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Estimated mean GFR from months 1 to 84, as estimated via mixed‐effects modeling (without imputation). In this model, time was regarded as a categorical variable.

For the sensitivity analysis in which GFR values that were missing due to patient death or graft loss were imputed as zero, mean eGFR plus or minus standard error for belatacept MI at months 12, 36, 60, and 84 was 43.9 ± 1.8, 42.5 ± 1.8, 39.0 ± 1.9, and 35.5 ± 2.0 mL/min per 1.73 m2, respectively. The corresponding values for belatacept LI were 44.1 ± 1.8, 42.5 ± 1.9, 39.6 ± 1.9, and 36.3 ± 1.9 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The corresponding values for CsA were 36.1 ± 1.8, 32.1 ± 1.9, 27.4 ± 2.0, and 25.5 ± 2.1 mL/min per 1.73 m2. With imputation, the effect of belatacept versus CsA at each time point remained statistically significant (p < 0.001 for overall treatment effect). Results from the slope‐based model with imputation showed that there was a mean decline in eGFR for all treatment regimens. The slope value was −0.77 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI −1.42 to −0.13) per year for belatacept MI and −0.80 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI −1.44 to −0.16) per year for belatacept LI. The corresponding value for the CsA‐based regimen was −1.17 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI −1.83 to −0.51). Compared with CsA, the slope estimates in the imputed analysis did not differ significantly for belatacept MI (p = 0.40) or LI (p = 0.43).

Acute rejection

The Kaplan–Meier cumulative event rates of acute rejection for belatacept MI, belatacept LI and CsA were 19.3%, 18.6%, and 17.3%, respectively, at month 36; 21.1%, 19.5%, and 17.3%, respectively, at month 60; and 21.1%, 19.5%, and 17.3%, respectively, at month 84. At month 84, the HR for the comparison of belatacept MI with CsA was 1.22 (95% CI 0.75–2.00; p = 0.43); the corresponding value for the comparison of belatacept LI with CsA was 1.15 (95% CI 0.70–1.90; p = 0.59). Potential cases of suspected antibody‐mediated acute rejection were identified post hoc and are described in Table S7.

Donor‐specific antibodies

The cumulative event rates of de novo DSAs at months 36, 60 and 84 for belatacept MI were 2.3%, 6.2% and 6.2%, respectively; the corresponding values for belatacept LI were 1.5%, 2.4%, and 4.5%, respectively, and the corresponding values for CsA were 11.3%, 17.1%, and 22.9%, respectively. At month 84, the HR for the comparison of belatacept MI with CsA was 0.26 (95% CI 0.11–0.59; p = 0.0001), and the HR for the comparison of belatacept LI with CsA was 0.18 (95% CI 0.07–0.46; p < 0.0001). Class I HLA specificity was detected in five belatacept MI–treated, three belatacept LI–treated, and 15 CsA‐treated patients. Class II HLA specificity was seen in two belatacept MI–treated and three CsA‐treated patients. In the CsA treatment arm, an additional four patients had DSAs with both class I and II HLA specificity.

Safety

Serious AEs occurred in 87.0% of belatacept MI–treated, 89.1% of belatacept LI–treated and 84.2% of CsA‐treated patients. Infections were the most common serious AE. Incidence rates of serious infections per 100 person‐years of study drug exposure were similar across the treatment arms (Table 1). The incidence rates of any‐grade viral infections per 100 person‐years of treatment exposure were 20.98, 17.45 and 19.05 for belatacept MI, belatacept LI and CsA, respectively. The corresponding values for the incidence rates of any‐grade fungal infections per 100 person‐years of treatment exposure were 9.79, 6.93 and 11.00. The incidence rates of any‐grade malignancies per 100 person‐years of treatment exposure were similar across the treatment arms (Table 2).

Table 1.

Cumulative incidence rates of selected serious adverse events adjusted per 100 person‐years of treatment exposure

| Belatacept MI (n = 184) | Belatacept LI (n = 175) | CsA (n = 184) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serious infectionsa , b | 22.67 | 16.52 | 20.32 |

| Urinary tract infection | 3.02 | 3.62 | 3.54 |

| Cytomegalovirus infection | 2.20 | 1.94 | 1.71 |

| Pneumonia | 1.76 | 1.50 | 1.41 |

| Pyelonephritis | 1.44 | 0.69 | 1.83 |

| Gastroenteritis | 0.93 | 0.69 | 1.02 |

| Herpes zoster | 0.93 | 0.34 | 0.38 |

| Sepsis | 0.80 | 1.14 | 1.93 |

| Urosepsis | 0.68 | 0.80 | 0.76 |

| Cellulitis | 0.57 | 0.45 | 0 |

| Gangrene | 0.46 | 0.22 | 0 |

| Pyelonephritis acute | 0.46 | 0.11 | 0.91 |

| Osteomyelitis | 0.46 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| Bacteremia | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.63 |

| Septic shock | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.75 |

| Escherichia urinary tract infection | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.64 |

| Bronchopneumonia | 0.11 | 0.45 | 0 |

| Serious gastrointestinal disordersc | 6.3 | 6.2 | 6.8 |

| Serious cardiac disordersc | 5.2 | 4.1 | 5.2 |

| Serious general disorders and administration site conditionsc | 3.9 | 3.1 | 4.6 |

| Serious blood and lymphatic system disordersc | 3.5 | 2.4 | 2.5 |

| Serious vascular disordersc | 3.1 | 5.1 | 5.4 |

| Serious investigations (laboratory parameters)c | 2.0 | 2.2 | 4.4 |

| Serious hepatobiliary disordersc | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| Serious endocrine disordersc | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

CsA, cyclosporine; LI, less intense; MI, more intense.

The duration (patient‐years) of patient exposure to assigned study drug was calculated from the randomization date to the event date, to the date of last follow‐up or to month 84, whichever was earliest.

Only preferred terms occurring in ≥2% of patients in any treatment arm are reported.

The duration (patient‐years) of patient exposure to assigned study drug was calculated from the randomization date to the event date, to the date of last dose of study medication plus 56 days or to month 84, whichever was earliest.

Table 2.

Cumulative incidence rates of any‐grade malignancy adjusted per 100 person‐years of treatment exposure

| Belatacept MI (n = 184) | Belatacept LI (n = 175) | CsA (n = 184) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any malignancya , b | 3.80 | 3.23 | 3.64 |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 1.05 | 0.69 | 1.55 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin | 0.93 | 0.68 | 0.51 |

| Bowen's disease | 0.46 | 0 | 0.25 |

| Prostate cancer | 0.23 | 0.46 | 0 |

CsA, cyclosporine; LI, less intense; MI, more intense.

The duration (patient‐years) of patient exposure to assigned study drug was calculated from the randomization date to the event date, to the date of last follow‐up or to month 84, whichever was earliest.

Only preferred terms occurring in two or more patients in any treatment arm are reported.

Nine patients experienced posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) prior to month 84 (n = 4, Epstein–Barr virus [EBV] positive; n = 5, EBV negative) (Table 3). Incidence rates per 100 person‐years of exposure in EBV‐positive patients treated with belatacept MI, belatacept LI and CsA were 0.12, 0.25 and 0.14, respectively. The corresponding values in EBV‐negative patients were 1.71, 5.19 and 0.00, respectively. Of those patients who had PTLD, five had primary central nervous system PTLD (n = 2, belatacept MI; n = 3, belatacept LI) and seven died (n = 3, belatacept MI; n = 4, belatacept LI). Two additional cases of PTLD were reported after month 84 but prior to database lock (n = 1, EBV‐positive patient randomized to belatacept MI; n = 1, EBV‐negative patient randomized to belatacept LI); the EBV‐negative patient randomized to belatacept LI who developed PTLD after month 84 also died.

Table 3.

Cumulative incidence rates of PTLD adjusted per 100 person‐years of treatment exposure

| Time period, mo | Patients, n (incidence rate) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Belatacept MI (n = 184) | Belatacept LI (n = 175) | CsA (n = 184) | |

| EBV positive | |||

| 0–12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12–24 | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.68) | 0 |

| 24–36 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 36–48 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | 0 |

| 48–60 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.37) |

| 60–84 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Overall | 1 (0.12)a | 2 (0.25) | 1 (0.14) |

| EBV negative | |||

| 0–12 | 1 (7.89) | 2 (11.88) | 0 |

| 12–48 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 48–60 | 0 | 2 (25.28) | 0 |

| 60–84 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Overall | 1 (1.71) | 4 (5.19)b | 0 |

CsA, cyclosporine; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; LI, less intense; MI, more intense; PTLD, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder.

One additional patient randomized to belatacept MI developed PTLD beyond month 84.

One additional patient randomized to belatacept LI developed PTLD beyond month 84.

Discussion

In this analysis of the final 7‐year results from BENEFIT‐EXT, recipients of extended criteria donor kidneys randomized to belatacept had graft survival rates that were similar to those seen in patients randomized to CsA; however, fewer belatacept LI–treated than CsA‐treated patients met the combined end point of first occurrence of death, graft loss or eGFR <20 mL/min per 1.73 m2, which corresponded to a 29% reduction in risk (p = 0.05). An eGFR threshold of ≤20 mL/min per 1.73 m2 is clinically meaningful, given that patients with GFR values in this range are approaching end‐stage renal disease and the need for retransplantation.

The improvement in GFR previously reported for belatacept versus CsA through 5 years of follow‐up was sustained and remained statistically significant at 7 years. The differences in eGFR between each belatacept‐based regimen and the CsA‐based regimen continued to increase over time. Trends from the slope‐based analysis with imputation are consistent with those from the slope‐based analysis without imputation; however, in the analysis with imputation, the difference between each belatacept‐based and the CsA‐based regimen did not remain statistically significant. A possible explanation is that there was clear differentiation of GFR slope estimates between regimens in the analysis without imputation, but by introducing zero values for GFR results that were missing due to death or graft loss, the slope estimates moved closer to each another; therefore, the difference between regimens became less pronounced, and statistical significance was lost. Notably, in a meta‐analysis of six clinical trials comparing belatacept with either CsA or tacrolimus, belatacept was associated with significantly greater eGFR at 12, 24 and 36 mo after transplant 32. This result is important from a clinical perspective because recipients of ECD kidneys tend to have statistically significantly lower GFR values than those who receive standard criteria donor kidneys 33, 34, 35, 36. A non‐nephrotoxic immunosuppressive regimen may help to maintain ECD renal function, delaying the time that recipients of such kidneys progress to chronic kidney disease, must return to maintenance dialysis and/or undergo retransplantation.

As in earlier analyses of the intent‐to‐treat population of BENEFIT‐EXT 28, 29, rates of biopsy‐proven acute rejection were statistically similar across treatment arms. Most cases of acute rejection occurred prior to month 36; thereafter, one case of acute rejection was reported in each of the belatacept treatment arms. No patient randomized to CsA experienced acute rejection after month 36.

Antibody‐mediated rejection has been identified as a major cause of late (>1 year after transplant) graft loss 21, 37, and the de novo development of DSAs is associated with significantly shorter graft survival 38, 39, 40, 41. In BENEFIT‐EXT, the cumulative incidence of de novo DSAs was statistically significantly lower in each belatacept‐based treatment arm versus the CsA‐based comparator regimen. This finding is consistent with data showing that the reduced strength of the CD28 signal, which is inhibited by belatacept, leads to a reduction in B cell responses 42; however, the significantly greater incidence of de novo DSA development among CsA‐treated patients also may have been the result of poorer treatment compliance. In BENEFIT‐EXT, information on study medication adherence was collected up to month 36 (Table S1).

The incidence of serious AEs, serious infections, any‐grade viral or fungal infections, and any‐grade malignancies was similar across all treatment arms, suggesting that the safety profile of belatacept over the long term is similar to that of CsA. Nevertheless, the risk of PTLD was greater among belatacept‐ versus CsA‐treated patients, particularly those who were EBV negative prior to transplant. It is for this reason that belatacept is contraindicated in patients who are EBV negative or whose EBV serostatus is unknown prior to transplant 43, 44.

In the present study, no difference in patient or graft survival was seen between belatacept‐ and CsA‐based immunosuppression. Analysis of the individual components of the composite end point showed an 11–12% increase in the risk of death and a 20–30% reduction in the risk of death‐censored graft loss for belatacept versus CsA at 7 years after transplant; neither sensitivity analysis was statistically significant. The lack of statistical significance for the composite end point in BENEFIT‐EXT contrasts with the survival advantage observed for belatacept versus CsA at 5 and 7 years after transplant in BENEFIT, which examined patients transplanted with a living or standard criteria donor kidney 45. In addition to kidney donor type, the discrepant findings between these two phase III trials can at least partially be attributed to the complementary rather than identical nature of the study populations: Kidney transplant recipients participating in BENEFIT were younger overall and had fewer comorbidities and thus were less likely to die with a functioning graft than were BENEFIT‐EXT participants.

BENEFIT‐EXT is the largest and, with 7 years of follow‐up, the longest randomized prospective clinical trial evaluating a non–calcineurin inhibitor–based immunosuppressive regimen in recipients of extended criteria donor renal allografts. A limitation of this 7‐year analysis is that not all randomized and transplanted patients were evaluable for the entire follow‐up period. Nonetheless, ≈70% of patients in each treatment arm completed treatment at month 12 (28), a 1‐year completion rate comparable to 46 or higher than 47 those reported in other randomized prospective registration trials. Moreover, almost 70% of the intent‐to‐treat population was evaluable for prospectively defined outcomes at month 84.

Another limitation is that donor kidneys in BENEFIT‐EXT were protocol defined by extended criteria that incorporated but were not limited to those consistent with the former United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) definition of ECD kidneys 48. When the protocol for BENEFIT‐EXT was being developed in 2003, these kidney subtypes were considered high risk under UNOS and other published criteria available at the time 8, 48; however, definitions of high‐risk kidneys have since evolved. In 2013, the Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI) was introduced 49; therefore, the above findings are not necessarily predictive of outcomes that might be observed among recipients of donor kidneys with high (>85%) KDPI scores. This is important because not all ECD kidneys are equivalent in terms of anticipated patient outcomes; some ECD kidneys may have more favorable KDPI scores than others 50. Future studies should incorporate the newer KDPI scoring paradigm. In summary, in this 7‐year analysis of BENEFIT‐EXT, in comparison to CsA, belatacept was associated with similar rates of patient and graft survival and acute rejection, sustained improvements in renal function and significantly lower cumulative incidence of detectable de novo DSAs.

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation. A. Durrbach has received research support from Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and his spouse was once an employee of Bristol‐Myers Squibb. S. Florman and M. del Carmen Rial have received research/grant support from Bristol‐Myers Squibb. L. Rostaing has served on speakers' bureaus for Novartis, Astellas, Veloxis, Fresenius, and LFB. A. Matas has received grant support from Bristol‐Myers Squibb. T. Wekerle has received honoraria and research grants from Bristol‐Myers Squibb. M. Polinsky, H. U. Meier‐Kriesche, and S. Munier are salaried employees of Bristol‐Myers Squibb. J. M. Grinyó has served as an advisor to Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Chiesi, Veloxis, Quark, and Opsona. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supporting information

Data S1: Supplementary material.

Table S1: Duration of follow‐up and treatment exposure in randomized, transplanted and treated patients.

Table S2: Kaplan–Meier survival rate for time to death or graft loss from randomization to month 84 (year 7; all randomized and transplanted patients).

Table S3: Kaplan–Meier survival rate for time to death from randomization to month 84 (year 7; all randomized and transplanted patients).

Table S4: Causes of death.

Table S5: Kaplan–Meier survival rate for time to death‐censored graft loss from randomization to month 84 (year 7; all randomized and transplanted patients).

Table S6: Causes of graft loss.

Table S7: Potential cases of suspected antibody‐mediated acute rejection.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the BENEFIT‐EXT investigators (see Supporting Information for complete list). Professional medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Tiffany DeSimone, PhD, of CodonMedical, an Ashfield Company, part of UDG Healthcare plc, and were funded by Bristol‐Myers Squibb.

Durrbach A, Pestana JM, Florman S, del Carmen Rial M, Rostaing L, Kuypers D, Matas A, Wekerle T, Polinsky M, Meier‐Kriesche HU, Munier S & Grinyó J. Long‐Term Outcomes in Belatacept‐ Versus Cyclosporine‐Treated Recipients of Extended Criteria Donor Kidneys: Final Results From BENEFIT‐EXT, a Phase III Randomized Study. Am J Transplant 2016; 16: 3192–3201

[The copyright line for this article was changed on June 19, 2017 after original publication.]

References

- 1. United States Renal Data System . 2014 Annual Data Report. Chapter 6: Transplantation. 2014. [cited 2015 May 19]. Available from: http://www.usrds.org/2014/view/v2_06.aspx.

- 2. Matas AJ, Smith JM, Skeans MA, et al. OPTN/SRTR . 2012 Annual Data Report: Kidney. Am J Transplant 2014; 14(suppl 1): 11–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Axelrod DA, McCullough KP, Brewer ED, Becker BN, Segev DL, Rao PS. Kidney and pancreas transplantation in the United States, 1999–2008: The changing face of living donation. Am J Transplant 2010; 10(4 Pt 2): 987–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Audard V, Matignon M, Dahan K, Lang P, Grimbert P. Renal transplantation from extended criteria cadaveric donors: Problems and perspectives overview. Transpl Int 2008; 21: 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Collins MG, Chang SH, Russ GR, McDonald SP. Outcomes of transplantation using kidneys from donors meeting expanded criteria in Australia and New Zealand, 1991 to 2005. Transplantation 2009; 87: 1201–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Metzger RA, Delmonico FL, Feng S, Port FK, Wynn JJ, Merion RM. Expanded criteria donors for kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 2003; 3(Suppl 4): 114–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ojo AO, Hanson JA, Meier‐Kriesche H, et al. Survival in recipients of marginal cadaveric donor kidneys compared with other recipients and wait‐listed transplant candidates. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001; 12: 589–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Port FK, Bragg‐Gresham JL, Metzger RA, et al. Donor characteristics associated with reduced graft survival: An approach to expanding the pool of kidney donors. Transplantation 2002; 74: 1281–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saidi RF, Elias N, Kawai T, et al. Outcome of kidney transplantation using expanded criteria donors and donation after cardiac death kidneys: Realities and costs. Am J Transplant 2007; 7: 2769–2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blanca L, Jiménez T, Cabello M, et al. Cardiovascular risk in recipients with kidney transplants from expanded criteria donors. Transplant Proc 2012; 44: 2579–2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. De Vusser K, Lerut E, Kuypers D, et al. The predictive value of kidney allograft baseline biopsies for long‐term graft survival. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; 24: 1913–1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Klintmalm G, Bohman SO, Sundelin B, Wilczek H. Interstitial fibrosis in renal allografts after 12 to 46 months of cyclosporin treatment: Beneficial effect of low doses in early post‐transplantation period. Lancet 1984; 2: 950–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Myers BD, Ross J, Newton L, Luetscher J, Perlroth M. Cyclosporine‐associated chronic nephropathy. N Engl J Med 1984; 311: 699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Palestine AG, Austin HA 3rd, Balow JE, et al. Renal histopathologic alterations in patients treated with cyclosporine for uveitis. N Engl J Med 1986; 314: 1293–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Starzl TE, Fung J, Jordan M, et al. Kidney transplantation under FK 506. JAMA 1990; 264: 63–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grinyó JM, Bestard O, Torras J, Cruzado JM. Optimal immunosuppression to prevent chronic allograft dysfunction. Kidney Int Suppl 2010; 119: S66–S70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Randhawa PS, Shapiro R, Jordan ML, Starzl TE, Demetris AJ. The histopathological changes associated with allograft rejection and drug toxicity in renal transplant recipients maintained on FK506. Clinical significance and comparison with cyclosporine. Am J Surg Pathol 1993; 17: 60–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nankivell BJ, Borrows RJ, Fung CL, O'Connell PJ, Allen RD, Chapman JR. The natural history of chronic allograft nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 2326–2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Halloran PF. Immunosuppressive drugs for kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 2715–2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weimert NA, Alloway RR. Renal transplantation in high‐risk patients. Drugs 2007; 67: 1603–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mohan S, Palanisamy A, Tsapepas D, et al. Donor‐specific antibodies adversely affect kidney allograft outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 23: 2061–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sellarés J, de Freitas DG, Mengel M, et al. Understanding the causes of kidney transplant failure: The dominant role of antibody‐mediated rejection and nonadherence. Am J Transplant 2012; 12: 388–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Squibb B‐M. Belatacept (NULOJIX) prescribing information. Princeton, NJ: Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bestard O, Campistol JM, Morales JM, et al. Advances in immunosuppression for kidney transplantation: New strategies for preserving kidney function and reducing cardiovascular risk. Nefrologia 2012; 32: 374–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Masson P, Henderson L, Chapman JR, Craig JC, Webster AC. Belatacept for kidney transplant recipients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 11: CD010699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Larsen CP, Pearson TC, Adams AB, et al. Rational development of LEA29Y (belatacept), a high‐affinity variant of CTLA4‐Ig with potent immunosuppressive properties. Am J Transplant 2005; 5: 443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wekerle T, Grinyó JM. Belatacept: From rational design to clinical application. Transpl Int 2012; 25: 139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Durrbach A, Pestana JM, Pearson T, et al. A phase III study of belatacept versus cyclosporine in kidney transplants from extended criteria donors (BENEFIT‐EXT study). Am J Transplant 2010; 10: 547–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pestana JO, Grinyo JM, Vanrenterghem Y, et al. Three‐year outcomes from BENEFIT‐EXT: A phase III study of belatacept versus cyclosporine in recipients of extended criteria donor kidneys. Am J Transplant 2012; 12: 630–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Charpentier B, Medina PJ, Del C Rial M, et al. Long‐term exposure to belatacept in recipients of extended criteria donor kidneys. Am J Transplant 2013; 13: 2884–2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1999; 130: 461–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Talawila N, Pengel LH. Does belatacept improve outcomes for kidney transplant recipients? A systematic review Transpl Int 2015; 28: 1251–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hwang JK, Park SC, Kwon KH, et al. Long‐term outcomes of kidney transplantation from expanded criteria deceased donors at a single center: Comparison with standard criteria deceased donors. Transplant Proc 2014; 46: 431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lionaki S, Kapsia H, Makropoulos I, et al. Kidney transplantation outcomes from expanded criteria donors, standard criteria donors or living donors older than 60 years. Ren Fail 2014; 36: 526–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goh CC, Ladouceur M, Peters L, Desmond C, Tchervenkov J, Baran D. Lengthy cold ischemia time is a modifiable risk factor associated with low glomerular filtration rates in expanded criteria donor kidney transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 2009; 41: 3290–3292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Frutos MA, Sola E, Mansilla JJ, Ruiz P, Martín‐Gómez A, Seller G. Expanded criteria donors for kidney transplantation: Quality control and results. Transplant Proc 2006; 38: 2371–2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Einecke G, Sis B, Reeve J, et al. Antibody‐mediated microcirculation injury is the major cause of late kidney transplant failure. Am J Transplant 2009; 9: 2520–2523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Worthington JE, Martin S, Al‐Husseini DM, Dyer PA, Johnson RW. Posttransplantation production of donor HLA‐specific antibodies as a predictor of renal transplant outcome. Transplantation 2003; 75: 1034–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wiebe C, Gibson IW, Blydt‐Hansen TD, et al. Evolution and clinical pathologic correlations of de novo donor‐specific HLA antibody post kidney transplant. Am J Transplant 2012; 12: 1157–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hidalgo LG, Campbell PM, Sis B, et al. De novo donor‐specific antibody at the time of kidney transplant biopsy associates with microvascular pathology and late graft failure. Am J Transplant 2009; 9: 2532–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Legendre C, Canaud G, Martinez F. Factors influencing long‐term outcome after kidney transplantation. Transpl Int 2014; 27: 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang CJ, Heuts F, Ovcinnikovs V, et al. CTLA‐4 controls follicular helper T‐cell differentiation by regulating the strength of CD28 engagement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112: 524–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Archdeacon P, Dixon C, Belen O, Albrecht R, Meyer J. Summary of the US FDA approval of belatacept. Am J Transplant 2012; 12: 554–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. European Medicines Agency . Nulojix: EPAR ‐ summary for the public. 2011. [cited 2015 May 19]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002098/human_med_001459.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124.

- 45. Vincenti F, Rostaing L, Grinyo J, et al. Belatacept and long‐term outcomes in kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 333–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tedesco Silva H Jr., Cibrik D, Johnston T, et al. Everolimus plus reduced‐exposure CsA versus mycophenolic acid plus standard‐exposure CsA in renal‐transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2010; 10: 1401–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kahan BD. Efficacy of sirolimus compared with azathioprine for reduction of acute renal allograft rejection: A randomised multicentre study. The Rapamune US Study Group. Lancet 2000; 356: 194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rosengard BR, Feng S, Alfrey EJ, et al. Report of the Crystal City meeting to maximize the use of organs recovered from the cadaver donor. Am J Transplant 2002; 2: 701–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network . Allocation calculators. 2014. [cited 2015 May 21]. Available from: http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/converge/resources/allocationcalculators.asp?index=81.

- 50. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network . A Guide to Calculating and Interpreting the Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI). 2014 [cited Jun 15]. Available from: optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/ContentDocuments/Guide_to_Calculating_Interpreting_KDPI.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1: Supplementary material.

Table S1: Duration of follow‐up and treatment exposure in randomized, transplanted and treated patients.

Table S2: Kaplan–Meier survival rate for time to death or graft loss from randomization to month 84 (year 7; all randomized and transplanted patients).

Table S3: Kaplan–Meier survival rate for time to death from randomization to month 84 (year 7; all randomized and transplanted patients).

Table S4: Causes of death.

Table S5: Kaplan–Meier survival rate for time to death‐censored graft loss from randomization to month 84 (year 7; all randomized and transplanted patients).

Table S6: Causes of graft loss.

Table S7: Potential cases of suspected antibody‐mediated acute rejection.