Abstract

Bronchial epithelial cells and pulmonary endothelial cells are thought to be the primary modulators of conducting airways and vessels, respectively. However, histological examination of both mouse and human lung tissue reveals that alveolar epithelial cells (AECs) line the adventitia of large airways and vessels and thus are also in a position to directly regulate these structures. The primary purpose of this perspective is to highlight the fact that AECs coat the adventitial surface of every vessel and airway in the lung parenchyma. This localization is ideal for transmitting signals that can contribute to physiologic and pathologic responses in vessels and airways. A few examples of mediators produced by AECs that may contribute to vascular and airway responses are provided to illustrate some of the potential effects that AECs may modulate.

Keywords: alveolar epithelial cell, inducible nitric oxide synthase, IL-33, receptor for advanced glycation end products, ventilation-perfusion mismatch

At a Glance Commentary

Alveolar epithelial cells are in close proximity to conducting airways and vessels. Several alveolar epithelial cell–derived molecules such as inducible nitric oxide synthase, IL-33, and receptor for advanced glycation end products provide examples of mechanisms by which alveolar epithelial cells may communicate with and modulate large airways and vessels.

The primary function of the lung is gas exchange, which occurs in the alveoli. Many studies have demonstrated how bronchial epithelial cells and pulmonary vascular endothelial cells modulate the airways and blood vessels, respectively. There are also significant data suggesting the involvement of immune cells and mesenchymal cells within and surrounding the airways and vessels. However, in general, research has not been focused on the potential role of alveolar epithelial cells (AECs) in modulating responses in conducting airways and pulmonary vessels. AECs, which line the adventitial surface of conducting airways and pulmonary vessels, are in an ideal location to directly modulate both upper airway and vascular responses. This concept is an important one to remember as more studies identify crucial roles for AEC-derived molecules in the pathogenesis of airway diseases such as asthma.

Normal Lung Physiology

Bronchial epithelial cells and vascular endothelial cells, which line the lumen of airways and pulmonary vessels, respectively, are known to regulate airway and vascular tone. However, the potential of AEC-mediated modulation of proximal conducting airway and vessel responses has yet to be considered fully and investigated thoroughly. The idea that AECs may play a direct role in upper airway physiology is often controversial, because AECs are thought to be distal to the bronchi, are not surrounded by smooth muscle cells, and function primarily in gas exchange. All tissues/organs are lined with epithelium or mesothelium on their outer surfaces, so it is not surprising that the adventitial surface of conducting airways and pulmonary vessels within the lung parenchyma are also lined with epithelial cells. The epithelial cells lining the adventitial surface of the conducting airways and blood vessels in both human (Figures 1 and 2) and mouse (not shown) lungs are, in fact, AECs. Because the outer adventitial circumference is greater than the circumference of the lumen, AECs are likely to have a potential to modulate bronchial and vascular effects that is at least similar to that of the bronchial epithelial cells and vascular endothelial cells, respectively. This is a practical setup because AECs, at the forefront of gas exchange, would be logical cells to communicate with airways and vessels in the regulation of ventilation-perfusion matching.

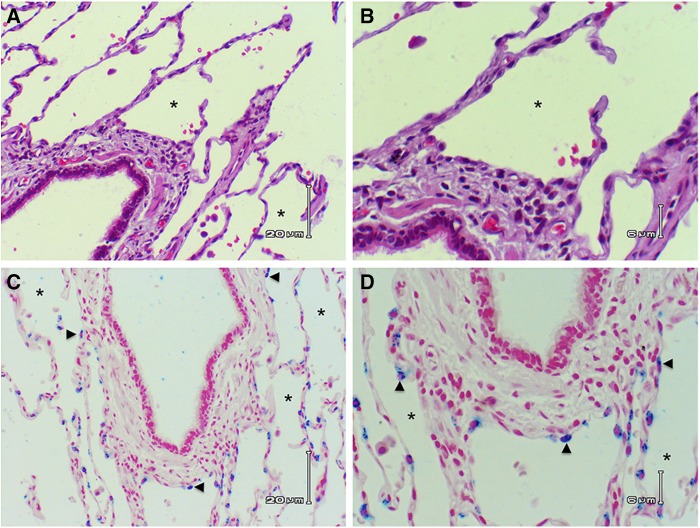

Figure 1.

Alveolar epithelial cells line the adventitial circumference of large airways. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin section of human lung showing bronchiole with ciliated columnar epithelium. Note that alveolar epithelium abuts the adventitia around the entire circumference of the airway, *Alveolar sac. (B) Higher-power image showing alveolar epithelial cells lining the adventitial surface of the larger airway. (C) Immunochemical staining of surfactant protein C (blue stain) highlights type II alveolar epithelial cells (arrowheads) lining the adventitial surface of a larger airway. (D) Higher power of the surfactant protein C–stained section showing the type II cells on the adventitial surface of the larger airway. (A and C) Scale bars: 20 μm. (B and D) Scale bars: 6 μm.

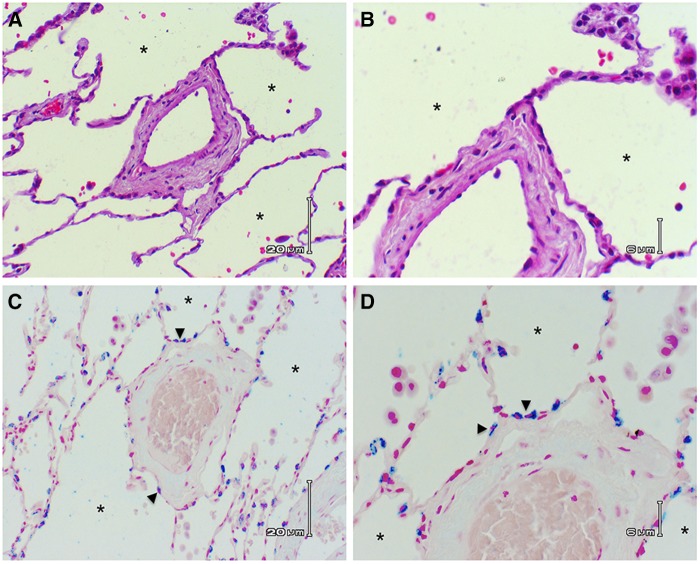

Figure 2.

Alveolar epithelial cells line the adventitial circumference of pulmonary vessels. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin section of human lung showing blood vessel surrounded by alveoli. Note that alveolar epithelium abuts the adventitia around the entire circumference of the vessel. *Alveolar sac. (B) Higher-power image showing alveolar epithelial cells lining the adventitial surface of the blood vessel. (C) Immunochemical staining of surfactant protein C (blue stain) highlights type II alveolar epithelial cells (arrowheads) lining the adventitial surface of a blood vessel. (D) Higher power of the surfactant protein C–stained section showing the type II cells on the adventitial surface of the blood vessel. (A and C) Scale bars: 20 μm. (B and D) Scale bars: 6 μm.

AEC-Derived Mediators of Airways and Vessels

Ventilation–Perfusion Matching

Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction is a physiological phenomenon in which blood vessels in the lung constrict to limit blood flow to areas of low ventilation (1). One mediator of this response is inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which uses arginine as well as O2 as substrates in nitric oxide (NO) production (2). Therefore, if Po2 is rate limiting, oxygenating the alveolar airspace may promote NO release from AECs. The oxygen concentration in the lung ranges from 1 to 260 μM, and the Michaelis constant of oxygen of iNOS in the lung is 135 μM, indicating that iNOS activity correlates with O2 levels in the lung as long as arginine is also available (3). Therefore, a ventilated alveolar space with increased O2 has the potential to promote an increase in NO production and, in turn, blood flow. Conversely, an unventilated airspace with low O2 may lead to decreases in NO and, in turn, blood flow. Thus, less NO would be expected to be produced in hypoxic environments (3, 4).

NO released from cells can have a rather high diffusing and signaling capacity, dependent on the amount of NO produced in proximity to the target cells and other factors such as superoxide levels (5, 6). For example, NO released by endothelial cells may diffuse to smooth muscle cells in vessels to cause vasodilatation, thus increasing blood flow to oxygenated areas of the lung. Type II AECs (AECII) express both NOS1 (constitutive NOS) and NOS2/iNOS, with iNOS being the primary NO producer during instances of AECII stimulation (7). Therefore, in a similar manner, NO released from AECII lining the adventitia of blood vessels may also diffuse to smooth muscle cells in the blood vessel, inducing vasodilation and increased blood flow in aerated areas of the lung.

Similarly, during inflammatory states when large amounts of immune cells are recruited to the lung tissue, blood flow to the lung may be increased via vasodilation of pulmonary vessels. Several studies have shown that iNOS expression in AECII increases and iNOS-mediated production of NO rises in response to inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α, and endotoxin, as well as during endotoxemia in vivo (7–9). There is evidence that NO production by AECIIs may surpass that of other cell types within the lungs (10), suggesting that AECs may be a major regulator of iNOS-mediated ventilation perfusion matching.

Innate Immunity

Another example of how AECs can directly affect upper airways and vessels is through the release of proinflammatory cytokines and mitogenic growth factors. AECs produce a plethora of proinflammatory mediators including macrophage chemoattractants (e.g., monocyte chemoattractant protein-1), neutrophil chemoattractants (e.g., IL-8), and eosinophil chemoattractants (e.g., eotaxins) (11, 12). AECIIs also play a crucial role in initiating antiviral IFN responses and antimicrobial responses (13, 14). Recent studies have identified important roles for epithelial-derived cytokines and receptors in the pathogenesis of lung diseases such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (reviewed in [15, 16]).

One of these molecules, the alarmin IL-33, has been shown to be a crucial mediator of allergic airway inflammatory responses after viral infection (17–20) or allergen exposure (21–27). IL-33 expression is most prominent in AECs, specifically AECII (28–31). When released from AECII, IL-33 has many direct and indirect proinflammatory downstream effects not only on the immune system, but also on airways and blood vessels. Proteomic and transcriptomic studies suggest that IL-33 directly activates signaling cascades (e.g., mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-κB) in a number of cell types including macrophages and endothelial cells, leading to enhanced expression of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and cell adhesion molecules (32, 33). IL-33 also triggers Th2 immune responses in the lung via activation of group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) (34–37), which are found abundantly in bronchovascular bundles (38). IL-33–induced activation of ILC2s leads to increased IL-13 levels in the lung and subsequent airway smooth muscle cell contraction, hyperreactivity, and mucus production (39). Therefore, AECII–ILC2 communication may serve as a bridge between the alveoli and conducting airways to mediate pulmonary pathology (40). Alveoli–endothelial cross-talk may also be mediated via IL-33. IL-33 has been shown to up-regulate intercellular vascular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression in endothelial cells (41, 42). This function is dependent on nuclear factor-κB signaling and promotes recruitment of immune cells from the blood to sites of inflammation.

A second molecule, the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), is a proinflammatory, immunoglobulin-like receptor that is highly expressed in the lung. Studies have localized RAGE expression to the basal membrane of type I AECs (AECI), and RAGE has been defined as a specific marker of AECI (43–46). Some researchers have also shown RAGE messenger RNA in AECII (47). Although located primarily on AECs in mice, pulmonary RAGE has been shown recently to be necessary for the development of asthma (a disease with primary pathology in conducting airways) in mouse models of allergic airway disease (48, 49). Mice lacking RAGE do not develop airway hyperresponsiveness, mucus hypersecretion, or eosinophilic inflammation in response to allergen exposure. RAGE knockout mice also had attenuated IL-33 levels in response to allergens, suggesting that RAGE is important for IL-33 production and/or release. More work is required in the field, but it is possible that RAGE on AECI triggers the release of IL-33 from AECII. RAGE, therefore, is another alveolar-associated molecule that appears to have important effects on upper airway physiology and disease pathogenesis.

Although the focus of this perspective is to highlight the proximity of highly active AECs to conducting airways and vessels, it should be noted that the resident alveolar macrophages may also contribute significantly to such cellular communications. Alveolar macrophages produce a plethora of signaling mediators that can regulate air and blood flow as well as inflammation. Cross-talk between two cell types has been shown to mediate alveolar macrophage adherence to AECs (50), AEC proliferation (51), pulmonary inflammation, phagocytosis, alveolar macrophage activation, and epithelial plasticity (52, 53).

Potential Future Approaches

AEC-derived mediators have extensive effects on conducting airways and pulmonary vessels under a variety of conditions and are implicated in a number of pulmonary diseases including asthma, COPD, pulmonary fibrosis, acute lung injury/adult respiratory distress syndrome, pneumonia, and others (16, 54, 55). The potential mechanisms suggested here should inspire researchers throughout the spectrum of pulmonary disease to begin investigating alveolar effects on conducting airways and vessels.

A number of in vivo and in vitro models are available to aid in these studies. Cell-type–specific transgenic mice targeting AECII (56) or AECI (57) may be used to determine the role of the specific alveolar-derived mediators in question. In addition, methods such as flow automated cell sorting or magnetic bead separation allow for the isolation and culture of specific cell types from the lungs; such cells can be used in complex coculture models that mimic physiologic conditions to determine the effects of alveolar epithelial cultures on endothelial, bronchial epithelial, smooth muscle, or inflammatory cells.

Final Thoughts

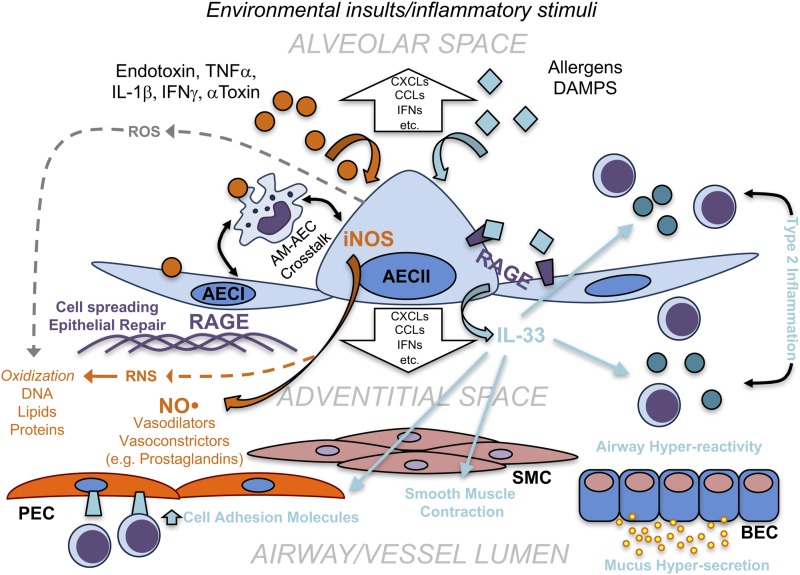

It is important to recognize the potential contributions of AECs to conducting airway and pulmonary vascular physiology and immune responses. Because gas exchange occurs in the alveolar parenchyma, it makes sense that AECs should contribute in modulating airway and vascular tone. In addition to highlighting the anatomic proximity of AECs to conducting airways and vessels, we have also illustrated the potential importance of AEC-derived signals on the conducting airways and vessels through a discussion of iNOS, IL-33, and RAGE signaling (summarized in Figure 3). The goal of this short perspective is to serve as a reminder to both lung biologists and clinical pulmonologists not to disregard AECs as important regulators of airways and vessels in studies of pulmonary diseases such as asthma, pulmonary hypertension, COPD, respiratory infection, pulmonary fibrosis, and lung cancer, and hopefully to inspire new studies that make discoveries concerning the importance of AECs in central airway and vascular physiology and pathology.

Figure 3.

Potential roles of alveolar-derived mediators in airway and vessel pathophysiological responses. Schematic representation of potential mechanisms of alveolar regulation of airways and vessels during physiologic and pathogenic processes. In the alveolar sac, environmental insults (e.g., endotoxin, α-toxin, and allergens), damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and inflammatory stimuli such as TNFα, IL-1β, or IFNγ stimulate the activation and response of type I and type II alveolar epithelial cells (AECI and AECII). Inflammatory mediators induce inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) activity and nitric oxide (NO) release from AECII (as well as other vasodilators and vasoconstrictors), which have the potential to induce pulmonary vessel contraction or dilation. During this process, damaging reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS) are produced, which can potentially lead to oxidation of DNA, lipids, and proteins. Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) mediates responses to environmental stimuli as well as DAMPs, which leads to downstream signaling via various mechanisms, including IL-33. RAGE also contributes to epithelial cell spreading and repair. Release of IL-33 into the adventitial space (or alveolar sac) has several effects on the alveolar, vascular, and conducting airway compartments. IL-33 increases expression of cell adhesion molecules on pulmonary endothelial cells (PEC), induces smooth muscle cell (SMC) contraction and type 2 inflammation in the conducting airways and respiratory airspace (alveolar sac). Type 2 inflammation surrounding bronchial epithelial cells (BEC) leads to mucus hypersecretion and airway hyperreactivity, as seen in asthma. Alveolar epithelial cells, which also interact with and communicate with alveolar macrophages (AM), also release a number of other inflammatory mediators (e.g., CXCL and CCL chemokines, IFN), which may regulate other inflammatory processes in both the alveolar region as well as the adventitia of airways and vessels.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Anuradha Ray (University of Pittsburgh) for her input on this manuscript. They also thank Dr. Claude Piantadosi (Duke University Medical Center) for his discussions concerning the possible role of alveolar cells in NO-dependent vascular responses.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Research Service Award 1F30ES024045 (E.A.O.), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Research Service Award 1T32HL129949-01A1 (T.N.P.), and American Heart Association 15GRNT25150004 (T.D.O.).

Author Contributions: E.A.O., T.N.P., and T.D.O.: wrote and edited the manuscript; and T.N.P. and T.D.O.: created the figures.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0151PS on January 12, 2017

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Sylvester JT, Shimoda LA, Aaronson PI, Ward JP. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:367–520. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson MA, Tuttle SW, Otto CM, Koch CJ. pO2-dependent NO production determines OPPC activity in macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dweik RA, Laskowski D, Abu-Soud HM, Kaneko F, Hutte R, Stuehr DJ, Erzurum SC. Nitric oxide synthesis in the lung. Regulation by oxygen through a kinetic mechanism. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:660–666. doi: 10.1172/JCI1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Cras TD, McMurtry IF. Nitric oxide production in the hypoxic lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L575–L582. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.4.L575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lancaster JR., Jr Simulation of the diffusion and reaction of endogenously produced nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8137–8141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lancaster JR., Jr A tutorial on the diffusibility and reactivity of free nitric oxide. Nitric Oxide. 1997;1:18–30. doi: 10.1006/niox.1996.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asano K, Chee CB, Gaston B, Lilly CM, Gerard C, Drazen JM, Stamler JS. Constitutive and inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression, regulation, and activity in human lung epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10089–10093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sunil VR, Connor AJ, Guo Y, Laskin JD, Laskin DL. Activation of type II alveolar epithelial cells during acute endotoxemia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L872–L880. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00217.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon S, George SC. Synergistic cytokine-induced nitric oxide production in human alveolar epithelial cells. Nitric Oxide. 1999;3:348–357. doi: 10.1006/niox.1999.0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutierrez HH, Pitt BR, Schwarz M, Watkins SC, Lowenstein C, Caniggia I, Chumley P, Freeman BA. Pulmonary alveolar epithelial inducible NO synthase gene expression: regulation by inflammatory mediators. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:L501–L508. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.3.L501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heiman AS, Abonyo BO, Darling-Reed SF, Alexander MS. Cytokine-stimulated human lung alveolar epithelial cells release eotaxin-2 (CCL24) and eotaxin-3 (CCL26) J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25:82–91. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chuquimia OD, Petursdottir DH, Rahman MJ, Hartl K, Singh M, Fernández C. The role of alveolar epithelial cells in initiating and shaping pulmonary immune responses: communication between innate and adaptive immune systems. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stegemann-Koniszewski S, Jeron A, Gereke M, Geffers R, Kröger A, Gunzer M, Bruder D. Alveolar type II epithelial cells contribute to the anti-influenza A virus response in the lung by integrating pathogen- and microenvironment-derived signals. MBio. 2016;7:e00276–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00276-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fehrenbach H. Alveolar epithelial type II cell: defender of the alveolus revisited. Respir Res. 2001;2:33–46. doi: 10.1186/rr36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lloyd CM, Saglani S. Epithelial cytokines and pulmonary allergic inflammation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2015;34:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hallstrand TS, Hackett TL, Altemeier WA, Matute-Bello G, Hansbro PM, Knight DA. Airway epithelial regulation of pulmonary immune homeostasis and inflammation. Clin Immunol. 2014;151:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, Abt MC, Alenghat T, Ziegler CG, Doering TA, Angelosanto JM, Laidlaw BJ, Yang CY, Sathaliyawala T, et al. Innate lymphoid cells promote lung-tissue homeostasis after infection with influenza virus. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1045–1054. doi: 10.1031/ni.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang YJ, Kim HY, Albacker LA, Baumgarth N, McKenzie AN, Smith DE, Dekruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Innate lymphoid cells mediate influenza-induced airway hyper-reactivity independently of adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:631–638. doi: 10.1038/ni.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonilla WV, Fröhlich A, Senn K, Kallert S, Fernandez M, Johnson S, Kreutzfeldt M, Hegazy AN, Schrick C, Fallon PG, et al. The alarmin interleukin-33 drives protective antiviral CD8+ T cell responses. Science. 2012;335:984–989. doi: 10.1126/science.1215418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byers DE, Alexander-Brett J, Patel AC, Agapov E, Dang-Vu G, Jin X, Wu K, You Y, Alevy Y, Girard JP, et al. Long-term IL-33-producing epithelial progenitor cells in chronic obstructive lung disease. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3967–3982. doi: 10.1172/JCI65570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barlow JL, Bellosi A, Hardman CS, Drynan LF, Wong SH, Cruickshank JP, McKenzie AN. Innate IL-13-producing nuocytes arise during allergic lung inflammation and contribute to airways hyperreactivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:191–198.e1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barlow JL, Peel S, Fox J, Panova V, Hardman CS, Camelo A, Bucks C, Wu X, Kane CM, Neill DR, et al. IL-33 is more potent than IL-25 in provoking IL-13-producing nuocytes (type 2 innate lymphoid cells) and airway contraction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:933–941. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartemes KR, Iijima K, Kobayashi T, Kephart GM, McKenzie AN, Kita H. IL-33-responsive lineage- CD25+ CD44(hi) lymphoid cells mediate innate type 2 immunity and allergic inflammation in the lungs. J Immunol. 2012;188:1503–1513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halim TY, Krauss RH, Sun AC, Takei F. Lung natural helper cells are a critical source of Th2 cell-type cytokines in protease allergen-induced airway inflammation. Immunity. 2012;36:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halim TY, Steer CA, Mathä L, Gold MJ, Martinez-Gonzalez I, McNagny KM, McKenzie AN, Takei F. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells are critical for the initiation of adaptive T helper 2 cell-mediated allergic lung inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40:425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamijo S, Takeda H, Tokura T, Suzuki M, Inui K, Hara M, Matsuda H, Matsuda A, Oboki K, Ohno T, et al. IL-33-mediated innate response and adaptive immune cells contribute to maximum responses of protease allergen-induced allergic airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2013;190:4489–4499. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Wang W, Huang P, Zhang Q, Yao X, Wang J, Lv Z, An Y, Corrigan CJ, Huang K, et al. Distinct sustained structural and functional effects of interleukin-33 and interleukin-25 on the airways in a murine asthma surrogate. Immunology. 2015;145:508–518. doi: 10.1111/imm.12465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yasuda K, Muto T, Kawagoe T, Matsumoto M, Sasaki Y, Matsushita K, Taki Y, Futatsugi-Yumikura S, Tsutsui H, Ishii KJ, et al. Contribution of IL-33-activated type II innate lymphoid cells to pulmonary eosinophilia in intestinal nematode-infected mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:3451–3456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201042109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Llop-Guevara A, Chu DK, Walker TD, Goncharova S, Fattouh R, Silver JS, Moore CL, Xie JL, O’Byrne PM, Coyle AJ, et al. A GM-CSF/IL-33 pathway facilitates allergic airway responses to sub-threshold house dust mite exposure. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardman CS, Panova V, McKenzie AN. IL-33 citrine reporter mice reveal the temporal and spatial expression of IL-33 during allergic lung inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:488–498. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snelgrove RJ, Gregory LG, Peiro T, Akthar S, Campbell GA, Walker SA, Lloyd CM. Alternaria-derived serine protease activity drives IL-33-mediated asthma exacerbations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:583–592.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollheimer J, Bodin J, Sundnes O, Edelmann RJ, Skånland SS, Sponheim J, Brox MJ, Sundlisaeter E, Loos T, Vatn M, et al. Interleukin-33 drives a proinflammatory endothelial activation that selectively targets nonquiescent cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:e47–e55. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.253427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinto SM, Nirujogi RS, Rojas PL, Patil AH, Manda SS, Subbannayya Y, Roa JC, Chatterjee A, Prasad TS, Pandey A. Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of IL-33-mediated signaling. Proteomics. 2015;15:532–544. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moro K, Yamada T, Tanabe M, Takeuchi T, Ikawa T, Kawamoto H, Furusawa J, Ohtani M, Fujii H, Koyasu S. Innate production of T(H)2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit(+)Sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. Nature. 2010;463:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature08636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neill DR, Wong SH, Bellosi A, Flynn RJ, Daly M, Langford TK, Bucks C, Kane CM, Fallon PG, Pannell R, et al. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature. 2010;464:1367–1370. doi: 10.1038/nature08900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Price AE, Liang HE, Sullivan BM, Reinhardt RL, Eisley CJ, Erle DJ, Locksley RM. Systemically dispersed innate IL-13-expressing cells in type 2 immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11489–11494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003988107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saenz SA, Siracusa MC, Perrigoue JG, Spencer SP, Urban JF, Jr, Tocker JE, Budelsky AL, Kleinschek MA, Kastelein RA, Kambayashi T, et al. IL25 elicits a multipotent progenitor cell population that promotes T(H)2 cytokine responses. Nature. 2010;464:1362–1366. doi: 10.1038/nature08901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nussbaum JC, Van Dyken SJ, von Moltke J, Cheng LE, Mohapatra A, Molofsky AB, Thornton EE, Krummel MF, Chawla A, Liang HE, et al. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells control eosinophil homeostasis. Nature. 2013;502:245–248. doi: 10.1038/nature12526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaur D, Gomez E, Doe C, Berair R, Woodman L, Saunders R, Hollins F, Rose FR, Amrani Y, May R, et al. IL-33 drives airway hyper-responsiveness through IL-13-mediated mast cell: airway smooth muscle crosstalk. Allergy. 2015;70:556–567. doi: 10.1111/all.12593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohapatra A, Van Dyken SJ, Schneider C, Nussbaum JC, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells utilize the IRF4-IL-9 module to coordinate epithelial cell maintenance of lung homeostasis. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:275–286. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Demyanets S, Konya V, Kastl SP, Kaun C, Rauscher S, Niessner A, Pentz R, Pfaffenberger S, Rychli K, Lemberger CE, et al. Interleukin-33 induces expression of adhesion molecules and inflammatory activation in human endothelial cells and in human atherosclerotic plaques. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2080–2089. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.231431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi YS, Park JA, Kim J, Rho SS, Park H, Kim YM, Kwon YG. Nuclear IL-33 is a transcriptional regulator of NF-κB p65 and induces endothelial cell activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;421:305–311. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fehrenbach H, Kasper M, Tschernig T, Shearman MS, Schuh D, Müller M. Receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) exhibits highly differential cellular and subcellular localisation in rat and human lung. Cell Mol Biol. 1998;44:1147–1157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dahlin K, Mager EM, Allen L, Tigue Z, Goodglick L, Wadehra M, Dobbs L. Identification of genes differentially expressed in rat alveolar type I cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31:309–316. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0423OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shirasawa M, Fujiwara N, Hirabayashi S, Ohno H, Iida J, Makita K, Hata Y. Receptor for advanced glycation end-products is a marker of type I lung alveolar cells. Genes Cells. 2004;9:165–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uchida T, Shirasawa M, Ware LB, Kojima K, Hata Y, Makita K, Mednick G, Matthay ZA, Matthay MA. Receptor for advanced glycation end-products is a marker of type I cell injury in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1008–1015. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1477OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katsuoka F, Kawakami Y, Arai T, Imuta H, Fujiwara M, Kanma H, Yamashita K. Type II alveolar epithelial cells in lung express receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;238:512–516. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Milutinovic PS, Alcorn JF, Englert JM, Crum LT, Oury TD. The receptor for advanced glycation end products is a central mediator of asthma pathogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:1215–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oczypok EA, Milutinovic PS, Alcorn JF, Khare A, Crum LT, Manni ML, Epperly MW, Pawluk AM, Ray A, Oury TD. Pulmonary receptor for advanced glycation end-products promotes asthma pathogenesis through IL-33 and accumulation of group 2 innate lymphoid cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:747–756.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hirano S. Interaction of rat alveolar macrophages with pulmonary epithelial cells following exposure to lipopolysaccharide. Arch Toxicol. 1996;70:230–236. doi: 10.1007/s002040050265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cakarova L, Marsh LM, Wilhelm J, Mayer K, Grimminger F, Seeger W, Lohmeyer J, Herold S. Macrophage tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces epithelial expression of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor: impact on alveolar epithelial repair. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:521–532. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200812-1837OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Speth JM, Bourdonnay E, Penke LR, Mancuso P, Moore BB, Weinberg JB, Peters-Golden M. Alveolar epithelial cell-derived prostaglandin E2 serves as a request signal for macrophage secretion of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 during innate inflammation. J Immunol. 2016;196:5112–5120. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bauer RN, Müller L, Brighton LE, Duncan KE, Jaspers I. Interaction with epithelial cells modifies airway macrophage response to ozone. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;52:285–294. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0035OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. Barrier epithelial cells and the control of type 2 immunity. Immunity. 2015;43:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sukkar MB, Ullah MA, Gan WJ, Wark PA, Chung KF, Hughes JM, Armour CL, Phipps S. RAGE: a new frontier in chronic airways disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167:1161–1176. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01984.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gui YS, Wang L, Tian X, Feng R, Ma A, Cai B, Zhang H, Xu KF. SPC-Cre-ERT2 transgenic mouse for temporal gene deletion in alveolar epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Flodby P, Borok Z, Banfalvi A, Zhou B, Gao D, Minoo P, Ann DK, Morrisey EE, Crandall ED. Directed expression of Cre in alveolar epithelial type 1 cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43:173–178. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0226OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]