Abstract

Background

Second anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears after reconstruction occur at a reported rate of 20% to 30%. This high frequency indicates that there may be factors that predispose an athlete to graft failure and ACL tears of the contralateral knee.

Purpose

To determine the incidence of second ACL injuries in a geographic population-based cohort over a 10-year observation period.

Study Design

Descriptive epidemiological study.

Methods

International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) codes relevant to the diagnosis of an ACL tear and the procedure code for ACL reconstruction were searched across the Rochester Epidemiology Project, a multidisciplinary county database, between the years of 1990 and 2000. This cohort of patients was tracked for subsequent ACL injuries through December 31, 2015. The authors identified 1041 patients with acute, isolated ACL tears. These patients were stratified by primary and secondary tears, sex, age, activity level, side of injury, sex by side of injury, and graft type.

Results

Of the 1041 unique patients with a diagnosed ACL tear in Olmsted County, Minnesota, from 1990 to 2000, there were 66 (6.0%) second ACL tears; 66.7% of these tears occurred on the contralateral side. A second ACL injury was influenced by graft type (P <.0001), election of ACL reconstruction (P = .0060), and sex by side of injury (P = .0072). Nonparametric analysis of graft disruption by graft type demonstrated a higher prevalence of second ACL tears with allografts compared with hamstring (P = .0499) or patellar tendon autografts (P = .0012).

Conclusion

The incidence of second ACL tears in this population-based cohort was 6.0%, with 66.7% of these tears occurring on the contralateral side from the original injury. There was a high population incidence of second ACL injuries in female patients younger than age 20 years. The utilization of patellar tendon autografts significantly reduced the risk of second ACL injuries compared with allografts or hamstring autografts in this cohort.

Keywords: anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), graft tear, epidemiology, incidence, secondary

A second anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury, either graft failure or contralateral ACL disruption, is even more devastating than the primary ACL tear.26 The risk of second ACL injuries after ACL reconstruction has been reported as high as between one-quarter to one-third,3,4,20 a drastically high recurrence of which some proportion may be preventable. ACL disruption is associated with destructive concomitant injuries, which include meniscus tears,16subchondral bone bruises, fractures, and articular cartilage lesions18 that can result in posttraumatic arthritis within 10 to 15 years.2,14 A reduction in subsequent ACL tears would decrease the significant burden on the patient and the economy, with annual costs that exceed $625 million in the United States.6,7,11

Previous studies of second ACL injuries have indicated that factors such as age,15,20,36,39 sex,20 activity level,1,15,20,39 time delay before ACL reconstruction (ACLR),31 and graft type15,20,36 predict further ACL injuries.21 ACLR is a common orthopaedic procedure, but many controversies remain in regards to the surgical technique, graft type, and rehabilita-tion.1,8,15,28,37,40 Geographically based epidemiological studiescan help to clarify these issues. Furthermore, with an increasing number of children engaged in high-level athletics and older patients who remain active longer,21 studies should examine geographic, population-based epidemiological trends with regard to second ACL injuries.

The purpose of this study was to (1) determine the incidence of second ACL injuries in a population-based cohort and (2) determine the risk factors associated with a second ACL injury. Our rationale for this study was that knowledge of both the historical and geographic-based incidence of second ACL injuries will (1) allow for improved understanding of the epidemiological progression of the disease and (2) assist in the prevention of second ACL inju-ries3,25,26 and the resultant sequelae.

Methods

The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) is a medical record linkage system that provides access to complete medical records for all residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, regardless of the medical facility in which the care was delivered.29,32-34 The REP database includes over 6.1 million health records. This population-based data infrastructure allows the complete determination and follow-up of all clinically diagnosed cases in a geographically defined commu-nity.29 In addition, the epidemiological data of the REP have demonstrated generalizability to larger populations.33

The REP database included all occurrences of ACL tears (based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD-9] billing codes consistent with an ACL injury) from January 1, 1990 through December 31, 2000. Second ACL injuries, defined as any ACL tear after a primary injury (either ipsilateral or contralateral), were tracked in this cohort of patients through December 31, 2015. Records were searched for evidence of a second ACL injury via orthopaedic examinations, arthroscopic examinations, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or surgical records of ACLR. The results yielded 1757 patients in the geographic locale. The medical records were individually reviewed by the authors (N.D.S., N.A.B., and T.L.S.) to confirm the accuracy of diagnosis and gather relevant data regarding treatment details and outcomes. From these 1757 patients, 519 were excluded from further analysis because of the confirmation of non-ACL injuries (eg, posterior cruciate ligament tears, meniscus injuries, absence of tears on MRI). After the exclusion of non-ACL injuries, 197 patients were identified with chronic tears (defined as a previous ACL tear on medical records not during 1990-2000), which resulted in 1041 patients with acute-onset, isolated ACL tears regardless of their reconstruction status. Of the 1041 unique patients, a total of 1107 ACL injuries occurred; 57 unique patients sustained 66 secondary ACL injuries. In addition, of the 1107 ACL injuries, 753 (68.0%) underwent treatment with ACLR. Within the 1041 patients, the factors that significantly contributed to a recurrent ACL injury to either knee (second injury) were identified. Multiple factors that were potentially predictive of a second ACL injury were examined, which included sex, age, activity level, sex by side, sex by activity level, side of injury, treatment group, and graft type. Local institutional review board approval was obtained from both the Mayo Clinic (14-003215) and Olmsted County Medical Center (026-OMC-14), and informed consent was obtained previously from all patients.

Because of the nature of second ACL injuries occurring either after nonoperative treatment or ACLR, it is important to note the disparity of possible second injuries that exists with these 2 populations. Whereas a patient who underwent ACLR can sustain a second injury via either a graft rupture or contralateral ACL rupture, a patient who underwent nonoperative treatment can only suffer a contralateral ACL rupture as the ipsilateral side will remain torn from the lack of reconstruction.

All statistical analyses were performed using JMP 10 (SAS Institute). The nonparametric Wilcoxon rank test and post hoc Wilcoxon Each Pair test were utilized for non-parametric factor analysis. One-way analyses of variance were utilized to calculate means with regard to the risk of second ACL injuries. Additional statistical analyses included a multivariate stepwise forward minimum Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and a Cox hazards model to determine the factors that likely contribute to a second injury. Statistical significance was set at a P value of <.05.

Results

The mean (±SD) occurrence of ACL tears per year from 1990 to 2000 in Olmsted County, Minnesota, from the REP database was 97.4 ± 13.4. Of the 1107 acute tears (mean age, 28.1 years; 683 male), 57 unique patients accounted for 66 (6.0%) second ACL tears (Table 1), with 9 patients experiencing an additional subsequent tear (either ipsilateral or contralateral) after a second ACL injury. Of all patients in this cohort, 33.6% were lost to follow-up, defined as no health record entry after January 1, 2011. The mean follow-up with patients was 13.6 ± 7.7 years.

Table 1. Demographics of ACL Tears (N = 1107)a.

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Acute ACL tears | |

| Male | 683 (61.7) |

| Female | 424 (38.3) |

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 28.1 6 10.1 |

| Tear type | |

| Complete | 1060 (95.8) |

| Partial | 42 (3.8) |

| Unknown | 5 (0.5) |

| Activity level | |

| Competitive | 246 (22.2) |

| Recreational | 689 (62.2) |

| Sedentary | 166 (15.0) |

| Unknown | 6 (0.5) |

| Occurrenceb | |

| Primary | 1041 (94.0) |

| Secondary | 66 (6.0)c |

| Failure | 22 (33.3) |

| Contralateral | |

| Reconstruction | 42 (63.6) |

| Nonoperative | 2 (3.0) |

Values are expressed as n (%) unless otherwise indicated. ACL, anterior cruciate ligament.

A primary injury is disruption of the anatomic ligament. A secondary injury includes either a failure of the graft or a tear to the contralateral knee.

Nine patients in this cohort experienced a subsequent ACL injury after a second ACL injury; this injury was also counted as a secondary ACL injury.

Of these second ACL tears (n = 66), 22 (33.3%) involved the ipsilateral ACL graft, and 44 (66.7%) involved the contralateral ACL. The overall graft failure rate for our sample that underwent previous ACLR was 2.9% (calculated from 753 injuries that underwent ACLR). Specifically observing athletes aged <20 years, the graft failure rate was 5.9%; for age <16 years, the graft failure rate was 1.8%. Allograft failure had the highest rate, with 26.9%, followed by hamstring autografts at 11.4% and patellar autografts at 6.3%. If nonoperative therapy was elected, the contralateral ACL had a 1.4% probability of tearing.

With regard to the activity level and injury risk, most patients who suffered an ACL tear identified themselves as recreational in their activity level (62.2%); competitive and sedentary levels were at 22.2% and 15.0%, respectively (Table 1). Analysis of the interaction between activity level and age group (F8 = 4.2351; P < .0001) determined that these 2 covariates acted dependently. The Wilcoxon test of activity level (Z2 = 0.0455; P = .9775) was not predictive of second ACL injuries. As some patients elect not to undergo ACLR and modify their activity level, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) of treatment group (ACLR vs non-operative), activity level, and a cross of treatment group by activity level would demonstrate an interaction of interest. However, as these data are categorical, ANCOVA was not possible. Rather, analysis of second injuries was run with treatment group by activity level. This analysis demonstrated that recreational athletes who elected ACLR were significantly more vulnerable to second injuries compared with those who elected nonoperative treatment (Z1 = 8.0396; P = .0046). Excluding graft retears from the analysis (n = 22), those who elected ACLR were more likely to experience a second injury than those who elected nonoperative treatment (Z1 = 9.0200; P = .0027).

The relative risk of a second ACL injury was assessed by age group; patients were stratified into 6 age groups. Most primary ACL tears by quantity occurred between the ages of 17 and 35 years (Table 2). With regard to second ACL tears, the age range of 17 to 25 years accounted for the majority of tears (Table 2). Male patients were more likely to sustain a primary ACL rupture compared with age-matched female patients between the ages of 17 to 45 years; female patients were more likely to sustain an ACL rupture at age ≤16 years (53.1%) (Table 2). Age approached significance for secondary injuries (Z5 = 10.7149; P = .0573), with significant post hoc differences between age ≤16 years versus 17-25 years (P = .0255), age ≤16 years versus 36-45 years (P = .0081), and age ≤16 years vs>55 years (P = .0007). It should be noted that the actual incidence of primary and secondary ACL tears decreased after the approximate age of 45 years and that sampling bias existed with age .55 years (Table 2). Stratification of analysis for sex by age group did not demonstrate a predictive value for second injuries. Stratification of sex by activity level and age group demonstrated significance for only predicting second injuries for competitive-level female patients between ages 17 and 25 years (Z1 = 5.6965; P = .0170).

Table 2. ACL Tears by Age Groupa.

| Age Range | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary tears | |||

| ≤16 | 61 (46.9) | 69 (53.1) | 130 (12.5) |

| 17-25 | 217 (63.6) | 124 (36.4) | 341 (32.8) |

| 26-35 | 226 (67.5) | 109 (32.5) | 335 (32.2) |

| 36-45 | 110 (63.2) | 64 (36.8) | 174 (16.7) |

| 46-55 | 25 (47.2) | 28 (52.8) | 53 (5.1) |

| .55 | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | 8 (0.8) |

| Total | 1041 | ||

| Secondary tears | |||

| ≤16 | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.0) |

| 17-25 | 12 (50.0) | 12 (50.0) | 24 (36.4) |

| 26-35 | 14 (73.7) | 5 (26.3) | 19 (28.8) |

| 36-45 | 9 (56.3) | 7 (43.8) | 16 (24.2) |

| 46-55 | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 3 (4.5) |

| .55 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 2 (3.0) |

| Total | 66 | ||

Values are expressed as n(%).ACL, anterior cruciate ligament.

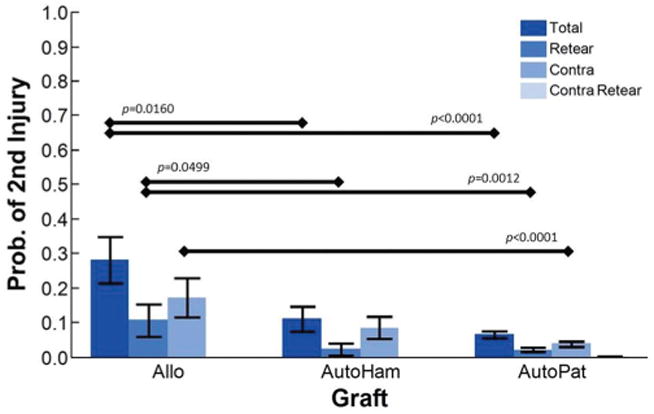

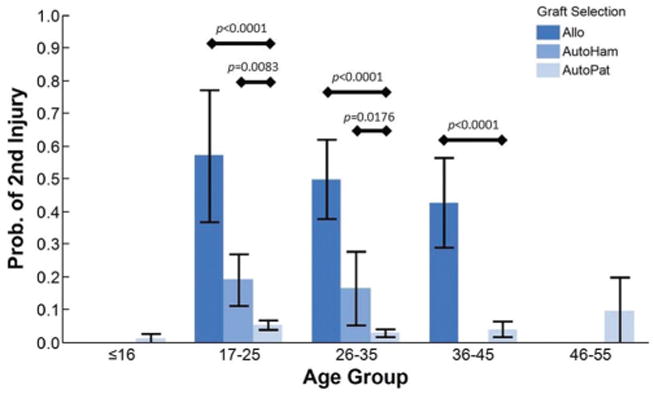

Graft type was statistically predictive for second ACL injuries (Z2 = 25.9875; P < .0001). Post hoc analysis showed that ACLR with allografts was predictive of second ACL injuries versus patellar tendon autografts (P< .0001) and allografts versus hamstring autografts (P = .0160) (Figure 1). For second injuries specific to a graft rupture (Z2 = 10.7326; P = .0047), post hoc analysis demonstrated that allografts were significant versus hamstring auto-grafts (P = .0499) and allografts versus patellar tendon autografts (P = .0012). Similarly, for contralateral tears (Z2 = 17.0647; P = .0002), post hoc analysis demonstrated that allografts were more predictive of a second injury versus patellar tendon autografts (P< .0001) (Figure 1). Overall, allografts were more likely to fail (28.3%) compared with hamstring and patellar autografts (11.3% and 6.8%, respectively) (Table 3). Stratification of graft type by age group predicted second injuries between the ages 17-25 years (Z2 = 29.4114; P< .0001), 26-35 years (Z2 = 53.7873; P< .0001), and 36-45 years (Z2 = 19.7579; P< .0001). Post hoc analyses demonstrated that for ages 17-25 years, allografts had a significantly higher probability for second injuries than patellar autografts (P< .0001), and hamstring autografts had a significantly higher probability than patellar autografts (P = .0083); for ages 26-35 years, allografts had a significantly higher probability than patellar autografts (P< .0001), and hamstring autografts had a significantly higher probability than patellar auto-grafts (P = .0176); and for ages 36-45 years, allografts had a significantly higher probability than patellar auto-grafts (P < .0001) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Probability of sustaining a second anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury by graft type. A value of 1 indicates a second ACL injury. Allo, allograft (hamstring or patellar); AutoHam, hamstring autograft; AutoPat, patellar autograft. All allografts were combined as only 4 were hamstring allografts.

Table 3. Statistical Analysis of Observed Epidemiological Factors for the Risk of Second ACL Injuriesa.

| Factor | Mean | n | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | .6533 | ||

| Male | 0.0571 | 683 | |

| Female | 0.0637 | 424 | |

| Activity levelb | .9775 | ||

| Sedentary | 0.0539 | 166 | |

| Recreational | 0.0581 | 689 | |

| Competitive | 0.0569 | 246 | |

| Age <20 y | .4127 | ||

| <20 y | 0.0496 | 282 | |

| ≥20 y | 0.0630 | 825 | |

| Age | .0573 | ||

| ≤16 y | 0.0152 | 132 | |

| 17-25 y | 0.0685 | 365 | |

| 26-35 y | 0.0537 | 354 | |

| 36-45 y | 0.0842 | 190 | |

| 46-55 y | 0.0536 | 56 | |

| >55 y | 0.2000 | 10 | |

| Age <20 y by competitive activity levelb | .3957 | ||

| <20 y | 0.0655 | 168 | |

| ≥20 y | 0.0385 | 78 | |

| Age <20 y by recreational activity levelb | .1315 | ||

| <20 y | 0.0273 | 110 | |

| ≥20 y | 0.0640 | 578 | |

| Age <20 y by sedentary activity levelb | .6300 | ||

| <20 y | 0.0000 | 4 | |

| ≥20 y | 0.0552 | 163 | |

| Side of injury | .0071 | ||

| Left | 0.0402 | 547 | |

| Right | 0.0786 | 560 | |

| Sex by left side | .0072 | ||

| Male | 0.0215 | 325 | |

| Female | 0.0676 | 222 | |

| Sex by right side | .2059 | ||

| Male | 0.0894 | 358 | |

| Female | 0.0594 | 202 | |

| Sex by age ≤16 y | .1374 | ||

| Male | 0.0317 | 63 | |

| Female | 0.0000 | 69 | |

| Sex by age 17-25 y | .1823 | ||

| Male | 0.0882 | 229 | |

| Female | 0.0524 | 136 | |

| Sex by age 26-35 y | .5739 | ||

| Male | 0.0583 | 240 | |

| Female | 0.0439 | 114 | |

| Sex by age 36-45 y | .5824 | ||

| Male | 0.0756 | 119 | |

| Female | 0.0986 | 71 | |

| Sex by age 46-55 y | .5147 | ||

| Male | 0.0741 | 27 | |

| Female | 0.0345 | 29 | |

| Sex by age >55 y | .1336 | ||

| Male | 0.0000 | 5 | |

| Female | 0.4000 | 5 | |

| Treatment | .0060 | ||

| No ACLR | 0.0311 | 354 | |

| ACLR | 0.0730 | 753 | |

| Graft typeb | <.0001 | ||

| Allograft | 0.2826 | 46 | |

| Hamstring autograft | 0.1125 | 80 | |

| Patellar autograft | 0.0677 | 620 |

A mean value that approximates 1 indicates an increased risk for second ACL injuries. Boldface indicates statistical significance. Italics indicate approaching or trending toward significance (P< .1). ACL, anterior cruciate ligament.

For each category, the total n value may deviate from 1107 as unknown classifications were removed from analysis.

Figure 2.

Probability of sustaining a second anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury by age group and graft type. A value of 1 indicates a second ACL injury. Allo, allograft (hamstring or patellar); AutoHam, hamstring autograft; AutoPat, patellar autograft. All allografts were combined as only 4 were hamstring allografts.

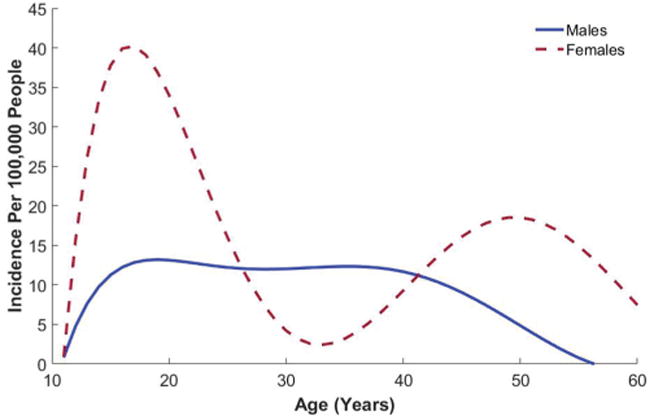

The Wilcoxon test demonstrated that sex was not predictive of second ACL injuries (Z1 = 0.2017; P = .6533). However, when the data were normalized to the population incidence, a trend of interest between sexes was visualized (Figure 3). Side of injury demonstrated significance for second injuries (Z1 = 7.2529; P = .0071). When stratified by type of second injury, graft ruptures demonstrated significance (Z1 = 8.7506; P= .0031), while contralateral tears did not (Z1 = 0.7499; P = .3865). Similar analyses of second injuries demonstrated significance with sex by left side (Z1 = 7.2262; P = .0072) but a lack of significance with sex by right side (Z1 = 1.6003; P = .2059).

Figure 3.

Age-specific incidence of second anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries in male and female patients. Data fit with a sixth-order polynomial.

Utilizing sex, age group, activity level, sex by side, sex by activity level, side of injury, and graft type as independent variables, the Cox hazards model (χ216 = 52.0608; P < .0001) demonstrated age group (P < .0001) as a significant factor for second ACL injuries. Stepwise BIC multivariate regression with the same independent variables as above demonstrated that the graft type of an allograft was the single significant independent variable predicting second ACL injuries (F1 = 93.8761; P< .0001) compared with patellar and hamstring autografts.

Discussion

This observational cohort study provides valuable information with regard to the reported rate of second ACL injuries from a geographic, population-based group of patients with acute-onset, isolated ACL tears. This data set complements the current, published epidemiological literature about the geographic occurrence of second ACL injuries.9,27,28 Pure geographic analyses are important epidemiological considerations as they are not exclusive to the incidence based on a particular hospital, subscribers to a particular healthinsurance company, or a physician community–based registry as has been reported previously in the litera-ture.19,20,36 This data set allows for improved generalizability of the epidemiological data to larger populations33 with minimal financial or social bias.

Overall, 6.0% of the acute-onset ACL tears in this population were second tears, with graft failure comprising 33.3% and contralateral tears comprising 66.7% of the total 66 second ACL tears observed. Within the contralateral tears, 2 (3.0%) were sustained by those who sought nonoperative treatment. Although at first glance this seems like a favorable statistic for nonoperative treatment, it is important to recognize that those who elect nonoperative therapy often adapt lifestyle, activity, and sport participation to avoid cutting, twisting, and planting maneuvers. Consequently, nonoperative treatment may not be the best method for all patients.

Analysis of treatment type for predicting second injuries was approached carefully because of the biased results that could have occurred from improper analysis. As those who were treated nonoperatively cannot experience a graft retear, only contralateral tears could be considered in the analysis. Thus, patients who experienced retears after ACLR were excluded (n = 22) from the analysis. It must also be assumed for the analysis that those who chose ACLR were more likely to expect a successful return to more active lifestyles. Many patients in this cohort first elected nonoperative treatment until their lifestyle and activity produced multiple “giving-way” episodes. Thus, their activity level was a covariate to their selection of treatment. Unfortunately, ANCOVA was not possible as it requires continuous variables and our data are categorical. Thus, because of the complexity of predicting contra-lateral tears by treatment type and the covariate of activity level, the rates of contralateral tears between the ACLR and nonoperative treatment populations are not straightforward and are difficult to report.

Activity level was not a statistically significant contributor to the injury risk in our geographic cohort but may be clinically significant as competitive-level athletes were twice as likely to sustain a second ACL injury when aged <20 years. Similarly, recreational athletes aged ≥20 years were twice as likely to sustain a second ACL injury (Table 3). This finding by age and activity level is consistent with the recent literature. It should be noted that our data did not allow for parsing via athletic exposure. Most patients who suffered an ACL tear in our cohort identified themselves as recreational in their activity level, followed by competitive. Being a competitive-level female patient between the ages of 17 and 25 years was particularly significant in predicting second ACL injuries. No other age range or activity level by sex demonstrated significance. Therefore, return-to-play criteria should be an important aspect of the clinical evaluation, especially with younger female competitive-level athletes.

Graft type also strongly influenced the occurrence of second ACL injuries. Our data indicated that allograft failure was nearly 3 to 4 times more likely than the failure of comparative autografts (Figure 1 and Table 3). In addition, hamstring autograft failure was 2 times more likely than patellar tendon autograft failure. A comparison of graft failure across age groups demonstrated that allografts failed more often than hamstring autografts and that hamstring autografts failed more often than patellar tendon autografts, especially at younger ages (Figure 2). This influence of graft type and patient age on ACLR failure has also recently been demonstrated by Kaedinget al.15 The graft selection for ACLR is important as current ACLR trends favor hamstring autografts from the contralateral limb. Recent publications from Scandinavian and Norwegian cruciate ligament registries have reported a 2-fold higher risk of revision with hamstring autografts compared with patellar tendon autografts.9,27 In addition, a meta-analysis by Xie et al41 concluded that patellar tendon autografts might allow patients to return to higher levels of activity and maintain rotational stability in comparison with hamstring autografts. However, the use of a patellar tendon autograft was associated with more postoperative complications.41 Concerns regarding selection bias in this cohort are minimal as the patellar autograft was the most highly favored of the graft types in this geographic cohort. Consequently, there were many more exposures of patellar autografts to second injuries than the other graft types. Future epidemiological studies should continue to identify the outcomes of the various graft selections to identify the optimal surgical technique and graft type for improved patient outcomes.

The highest prevalence of second ACL injuries was found between ages 17 and 35 years with both sexes (Table 2). On the basis of the previous literature, young female patients are more vulnerable to a second injury because of unmodified risk factors that may have led to their primary ACL injury.5,11-13,23 In the current cohort, sex was not predictive of a second ACL tear. However, side of injury and sex by side of injury were predictive of second ACL injuries, with female patients sustaining a higher likelihood of a second injury to their left side. This finding is most likely coincidental unless female patients have less neuromuscular control on the predominately nondominant limb in the generalized population. Further data will need to be assessed to determine whether there is a true trend in this phenomenon.

Although age alone was not statistically predictive of second ACL injuries, it was predictive in the Cox hazards model for contributing to a second ACL injury. Adjusting the overall second injury occurrence to the geographic population displayed a higher risk for young female patients to sustain a second ACL injury (Figure 3), consistent with the current literature.20,26 Of particular interest is the biphasic occurrence of second ACL injuries for female patients with peaks at near 18 and 50 years of age. Although the trend for male patients was relatively steady across age 15 to 45 years, the higher risk of second ACL injuries for female patients aged <20 years is consistent with the recent report by Wiggins et al.39 The reported second ACL injury rate of 12.6% for patients aged <20 years is higher than the mean injury rate in the current geographic analysis (5.9%).39 However, our second ACL injury rates from the total population are similar as we observed an ipsilateral tear rate of 2.1% and contralateral tear rate of4.2%.38,39

An important strength of the current study is the use of a large geographically defined database, but the population is limited to Olmsted County in southeast Minnesota. Additional strengths of the study include the reporting of sex, age, and activity level; chart-based verification; determination of associated injuries; and ability to account for all care provided. In addition, our analysis is not limited by only observing ACL tears in a particular age range. The reported data are strictly based on athletic trends in the United States. Other countries may have a different incidence of second ACL injuries on the basis of their unique exposure to high-risk sports with cutting, pivoting, and rapid deceleration. Likewise, these data must be viewed as representing the years from 1990 to 2000 and the surgical and rehabilitation sequences of that period. Changes in graft fixation and location may alter the overall picture of a second ACL injury. Activity level was documented from medical records and did not utilize a validated questionnaire (such as the International Knee Documentation Committee, Cincinnati, or Marx scores), which limits conclusions that may be drawn regarding the true activity level. In addition, we cannot accurately report the rate of return to sport and at the designated level of participation as these data were not documented in the medical records.

Future studies should examine trends of a second ACL injury over longer and more recent observation periods as societal trends are likely to change. Our current plan is to continue our analysis of the REP epidemiological data for years 2001 to 2015 and report the incidence of second ACL injuries in this cohort. In addition, we will report trends observed in the REP data that follow changes in the approach to ACLR and graft type selection.

Conclusion

In this population-based cohort of 1041 unique patients, the incidence of second ACL tears was 6.0%, involving the ACL graft in 33.3% and the contralateral ACL in 66.7%. Overall, graft selection was the most significant risk factor for second ACL injuries. Specifically, patellar autografts significantly reduced second ACL tears compared with hamstring autografts and allografts. Age was a determinant for graft failure and was a significant contributor to second ACL injuries in the stepwise BIC multivariate regression model. Female patients aged <20 years sustained a high incidence of second ACL injuries. It is likely that the trends in ACL injuries will change with improved reconstruction techniques and improved rehabilitation protocols. Future efforts should emphasize targeting prevention and outcome measures of high-risk groups, specifically activity modification, improved rehabilitation guidelines,3,10,24,30 and use of integrative neuromuscular training3,22,30,35 to help athletes reduce the risk of second ACL injuries.3,39

Acknowledgments

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: Funding was received from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases: R01AR 056259 to T.E.H. and T32AR056950 and L30AR070273 to N.D.S. This study was also made possible using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01AG034676.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Borchers JR, Pedroza A, Kaeding C. Activity level and graft type as risk factors for anterior cruciate ligament graft failure: a case-control study. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(12):2362–2367. doi: 10.1177/0363546509340633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bozynski CC, Kuroki K, Stannard JP, et al. Evaluation of partial tran-section versus synovial debridement of the ACL as novel canine models for management of ACL injuries. J Knee Surg. 2015;28(5):404–410. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1544975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Stasi S, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Neuromuscular training to target deficits associated with second anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 2013;43(11):777–792. A1–A11. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2013.4693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dodwell E, LaMont L, Green D, Pan T, Marx R, Lyman S. 20 years of pediatric anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in New York state. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(3):675–680. doi: 10.1177/0363546513518412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford KR, Myer GD, Schmitt LC, Uhl TL, Hewett TE. Preferential quadriceps activation in female athletes with incremental increases in landing intensity. J Appl Biomech. 2011;27(3):215–222. doi: 10.1123/jab.27.3.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ford KR, Myer GD, Toms HE, Hewett TE. Gender differences in the kinematics of unanticipated cutting in young athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(1):124–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freedman KB, Glasgow MT, Glasgow SG, Bernstein J. Anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction among university students. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;356:208–212. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199811000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frobell RB, Roos EM, Roos HP, Ranstam J, Lohmander LS. A randomized trial of treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tears. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(4):331–342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gifstad T, Foss OA, Engebretsen L, et al. Lower risk of revision with patellar tendon autografts compared with hamstring autografts: a registry study based on 45,998 primary ACL reconstructions in Scandinavia. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2319–2328. doi: 10.1177/0363546514548164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hewett TE, Di Stasi SL, Myer GD. Current concepts for injury prevention in athletes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sport Med. 2013;41(1):216–224. doi: 10.1177/0363546512459638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hewett TE, Ford KR, Myer GD. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes, part 2: a meta-analysis of neuromuscular interventions aimed at injury prevention. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(3):490–498. doi: 10.1177/0363546505282619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes, part 1: mechanisms and risk factors. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(2):299–311. doi: 10.1177/0363546505284183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, et al. Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(4):492–501. doi: 10.1177/0363546504269591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, Paterno MV, Quatman CE. The 2012 ABJS Nicolas Andry Award. The sequence of prevention: a systematic approach to prevent anterior cruciate ligament injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(10):2930–2940. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2440-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaeding CC, Pedroza AD, Reinke EK, et al. Risk factors and predictors of subsequent ACL injury in either knee after ACL reconstruction: prospective analysis of 2488 primary ACL reconstructions from the MOON cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1583–1590. doi: 10.1177/0363546515578836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler MA, Behrend H, Henz S, Stutz G, Rukavina A, Kuster MS. Function, osteoarthritis and activity after ACL-rupture: 11 years follow-up results of conservative versus reconstructive treatment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16(5):442–448. doi: 10.1007/s00167-008-0498-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HS, Seon JK, Jo AR. Current trends in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2013;25(4):165–173. doi: 10.5792/ksrr.2013.25.4.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy YD, Hasegawa A, PatilS, Koziol JA, Lotz MK, D'Lima DD. Histopathological changes in the human posterior cruciate ligament during aging and osteoarthritis: correlations with anterior cruciate ligament and cartilage changes. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(2):271–277. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maletis GB, Inacio MCS, Funahashi TT. Analysis of 16,192 anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions from a community-based registry. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(9):2090–2098. doi: 10.1177/0363546513493589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maletis GB, Inacio MCS, Funahashi TT. Risk factors associated with revision and contralateral anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions in the Kaiser Permanente ACLR registry. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(3):641–647. doi: 10.1177/0363546514561745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mall NA, Chalmers PN, Moric M, et al. Incidence and trends of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the United States. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2363–2370. doi: 10.1177/0363546514542796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myer GD, Chu DA, Brent JL, Hewett TE. Trunk and hip control neuromuscular training for the prevention of knee joint injury. Clin Sport Med. 2008;27(3):425–448, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myer GD, Ford KR, Khoury J, Succop P, Hewett TE. Biomechanics laboratory-based prediction algorithm to identify female athletes with high knee loads that increase risk of ACL injury. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(4):245–252. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.069351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myer GD, Paterno MV, Ford KR, Quatman CE, Hewett TE. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: criteria-based progression through the return-to-sport phase. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36(6):385–402. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2006.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paterno MV, Kiefer AW, Bonnette S, et al. Prospectively identified deficits in sagittal plane hip-ankle coordination in female athletes who sustain a second anterior cruciate ligament injury after anteriorcruciate ligament reconstruction and return to sport. Clin Biomech. 2015;30(10):1094–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paterno MV, Rauh MJ, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Hewett TE. Incidence of contralateral and ipsilateral anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury after primary ACL reconstruction and return to sport. Clin J Sport Med. 2012;22(2):116–121. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318246ef9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Persson A, Fjeldsgaard K, Gjertsen JE, et al. Increased risk of revision with hamstring tendon grafts compared with patellar tendon grafts after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a study of 12,643 patients from the Norwegian Cruciate Ligament Registry, 2004-2012. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):285–291. doi: 10.1177/0363546513511419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahr-Wagner L, Thillemann TM, Pedersen AB, Lind M. Comparison of hamstring tendon and patellar tendon grafts in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in a nationwide population-based cohort study: results from the Danish registry of knee ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):278–284. doi: 10.1177/0363546513509220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocca W, Yawn B, St. Sauver J, Grossardt B, Melton L. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1202–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schilaty ND, Nagelli CV, Hewett TE. Use of objective neurocognitive measures to assess the psychological states that influence return to sport following injury. Sport Med. 2015;46(3):299–303. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0435-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sri-Ram K, Salmon LJ, Pinczewski LA, Roe JP. The incidence of secondary pathology after anterior cruciate ligament rupture in 5086 patients requiring ligament reconstruction. Bone Joint J. 2013;95(1):59–64. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B1.29636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.St. Sauver J, Grossardt B, Yawn B, et al. Data resource profile: the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records-linkage system. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(6):1614–1624. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.St. Sauver J, Grossardt B, Yawn B, Melton L, Rocca W. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(9):1059–1068. [Google Scholar]

- 34.St. Sauver J, Grossardt B, Yawn B, Melton L, Rocca W. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester Epidemiolgoy Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(9):1059–1068. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sugimoto D, Myer GD, Foss KD, Hewett TE. Specific exercise effects of preventive neuromuscular training intervention on anterior cruciate ligament injury risk reduction in young females: meta-analysis and subgroup analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(5):282–289. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tejwani SG, Chen J, Funahashi TT, Love R, Maletis GB. Revision risk after allograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: association with graft processing techniques, patient characteristics, and graft type. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(11):2696–2705. doi: 10.1177/0363546515589168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaishya R, Agarwal AK, Ingole S, Vijay V. Current trends in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a review. Cureus. 2015;7(11):e378. doi: 10.7759/cureus.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Webster KE, Feller JA, Leigh WB, Richmond AK. Younger patients are at increased risk for graft rupture and contralateral injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(3):641–647. doi: 10.1177/0363546513517540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiggins AJ, Grandhi RK, Schneider DK, Stanfield D, Webster KE, Myer GD. Risk of secondary injury in younger athletes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(7):1861–1876. doi: 10.1177/0363546515621554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wright RW, Haas AK, Anderson J, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation: MOON guidelines. Sports Health. 2014;7(3):239–243. doi: 10.1177/1941738113517855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xie X, Liu X, Chen Z, Yu Y, Peng S, Li Q. A meta-analysis of bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft versus four-strand hamstring tendon autograft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee. 2015;22(2):100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]