Abstract

Objectives

The current study explores disidentification. Ethnic/racial disidentification is defined as psychological distancing from a threatened social identity to preserve a positive sense of self. The first study goal was to explore how daily ethnic/racial stereotype appraisal is related to ethnic/racial disidentification. The second goal was explore the association between disidentification and psychological mood. In both cases, centrality and private regard were considered individual differences that might moderate daily associations.

Method

Ethnic/racial minority young adults (Mage = 20.63 years, SD = 1.49; N = 129) completed a 21-day daily diary, including ethnic/racial stereotype a appraisal, ethnic/racial disidentification, and mood. At the end of the study, participants completed measures of ethnic/racial centrality and private regard.

Results

The effect of daily stereotype appraisal on disidentification depended on feelings of centrality and private regard. Young adults reporting high centrality and high private regard reported higher disidentification on days on which they reported more stereotype appraisal. These same young adults also reported higher negative mood on days on which they reported disidentification. Young adults reporting high private regard reported less positive mood on days on which they reported disidentification, whereas those reporting low private regard reported more positive mood.

Conclusion

This article discusses the role of ethnic/racial disidentification as a normative negotiation of threats to ethnic/racial identity development. For young adults who report high levels of centrality and private regard, daily encounters with ethnic/racial stereotypes are associated with more disidentification, but that disidentification comes at a cost in the form of more negative daily mood.

Keywords: ethnic/racial identity, disidentification, stereotypes, diaries

Ethnic/racial identity (ERI) serves several purposes. During adolescence and young adulthood, perhaps one of the most important purposes is to provide a sense of social connection and belonging to similar others (Phinney, 1990). Connection to similar others provides a sense of comfort, belonging, and positive self-regard (Frable, Platt, & Hoey, 1998). However, as members of many social categories, individuals have options as to how they maintain a positive sense of self (Kiang, Yip, & Fuligni, 2008). As theorized by social identity theory (SIT), an individual selects to affiliate with relevant social identities, depending on contextual demands, with the ultimate goal of maintaining a positive sense of self (Hogg & Terry, 2000; Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987). Because ERI is dynamic and responds to contextual cues, mechanisms for maintaining a positive self-regard will also vary according to the immediate context (Ashmore, Deaux, & McLaughlin-Volpe, 2004). For example, in contexts in which an ERI is supported (e.g., family gathering), an individual will likely embrace or affirm that identity (Phinney, Romero, Nava, & Huang, 2001). On the other hand, in contexts where an identity is threatened (e.g., being the target of a stereotype), the same individual may opt to distance him-/herself from the identity (Hogg, Terry, & White, 1995; Reid & Hogg, 2005).

The current study focused on the latter phenomenon: When do young adults who might still be developing an ERI choose to distance psychologically from that identity? The construct of disidentification was first introduced by Rothman (1960) and later revisited by Driedger (1976) as ethnic denial, a strategy employed by individuals from marginalized groups to cope with the impact of negative stereotypes about one’s ethnic group. Recent research has supported this claim, finding that individuals typically engage in disidentification when an identity is under threat (Bizman & Yinon, 2002; Hodson & Esses, 2002; Peetz, Gunn, & Wilson, 2010); and disidentification serves to alleviate the threat to the individual’s positive sense of self. The current study focused on a specific form of identity threat: feeling like one has been influenced by an ethnic/racial stereotype. Disidentification is defined as “one’s cognitive distancing of a social identity from a group identity due to the perception that one is distant from the group prototype or norm” and that “disidentification with an in-group may be used as a defensive mechanism” (Elsbach & Bhattacharya, 2001, p. 399). In other words, disidentification is a situation-specific decision that individuals make about the extent to which they choose to embrace or distance themselves from an ingroup. Disidentification differs from low identification in that it is an explicit expression of distance from a social group rather than a weak endorsement of a group membership. In the current study, “the group prototype or norm” is expressed through feeling influenced by an ethnic/ racial group stereotype. In a study of organizational disidentification, researchers found that disidentification was primarily motivated by an effort to maintain a positive sense of self (Elsbach & Bhattacharya, 2001). In other words, individuals often choose to disidentify to create distance between themselves and negative attributes of a group. It is also important to note that individuals can only disidentify from groups of which they are members, and, despite a decision to disidentify in a particular instance or situation, the individual remains a member of that social group.

Young adulthood has been implicated as an especially important time for identity development. Although current research in social and experimental psychology has observed that adults who have crystallized social identities are quick to distance from a threatened identity (Arndt, Greenberg, Schimel, Pyszczynski, & Solomon, 2002; Elsbach & Bhattacharya, 2001), it remains unclear whether similar patterns would be observed for young adults who are still undergoing identity construction. If similar patterns are observed for young adults, this may suggest that disidentification is a component of normative identity development. Employing daily diary techniques, the first goal of this study was to explore the daily-level association between ethnic/racial stereotype appraisal and disidentification, with the possibility that individual differences in ethnic/racial centrality (i.e., the importance of ERI to one’s overall identity) and private regard (i.e., how positively one feels about his or her ethnic/racial group membership) might moderate this association. The final goal of the study was to examine the association between ethnic/racial disidentification and daily feelings. Again, possible individual differences in centrality and private regard were explored.

SIT and Disidentification

According to SIT, individuals are motivated to view ingroups positively in order to maintain a positive sense of self. Despite motivations to maintain positive self-esteem and self-enhancement, all social groups are ascribed negative traits or attributes. At the same time, researchers have found that individuals in marginalized groups are able to buffer the negative effects of threatened identities (Crocker, Major, & Steele, 1998). For example, when individuals are faced with negative aspects of their social group, SIT posits that individuals will choose to create distance or disidentify with that social group: “another strategy to protect self-esteem is to deny one’s group membership or distance from the negatively perceived group” (Arndt et al., 2002, p. 28). Indeed, research has found that individuals will disidentify with an identity when embracing that identity poses a threat to one’s self-esteem. Among young adult and adult participants, Elsbach and Bhattacharya (2001) observed that individuals disidentify from an organizational identity to avoid associations with negative stereotypes. Specifically, “disidentifications appeared to be motivated by respondents’ desires to maintain and affirm a positive sense of self by separating themselves from the salient but unattractive reputation” of an ingroup (Elsbach & Bhattacharya, 2001, p. 400).

Perhaps the most pervasive way in which negative impressions of groups are transmitted is through stereotypes. Ethnic/racial stereotypes are ubiquitous and have been demonstrated to influence individuals’ thoughts and behaviors (Steele & Aronson, 1995). Although there is some evidence that positive stereotypes can bolster or boost performance on diagnostic tests under stereotype threat conditions (Armenta, 2010; Shih, Pittinsky, & Ambady, 1999), other research has found that even positive stereotypes can have negative effects (Cheryan & Bodenhausen, 2000; Ying et al., 2001). The current study explored how appraisal of a self-relevant ethnic/racial stereotype is related to psychological feelings, irrespective of the valence or content of the stereotype. Namely, daily stereotype appraisal was operationalized as a self-report measure of the extent to which a young adult feels that she or he has been personally affected by an ethnic/racial stereotype each day.

The Effects of Stereotypes on Disidentification

When individuals are reminded of a negative aspect of their social group, they are more likely to distance themselves from that identity (Arndt et al., 2002). In a study of Hispanic participants, when exposed to negative thoughts about Hispanic culture, participants were more likely to judge Hispanic paintings negatively. The authors concluded that being reminded of negative traits of one’s group leads individuals to create distance between themselves and the group. As such, disidentification is a within-person response based on the stimuli in a particular context. Research has found that individuals disidentify when an ingroup identity is threatened (Abrams & Hogg, 1988; Crocker & Luhtanen, 1990; Rubin & Hewstone, 1998). From the stereotype threat literature, Steele and Aronson (1995) found that, under conditions of stereotype threat, Black students were less likely to endorse stereotype-relevant items (e.g., “How much to do you enjoy sports?”). The authors interpreted this to mean that in cases where individuals are positioned to confirm a negative stereotype about their group, they create distance from the threatened identity. Similar patterns have been observed for organizational identities where an organization’s negative reputation and stereotypes have been identified as antecedents to disidentification (Elsbach & Bhattacharya, 2001). Building off the current theory and research, stereotype appraisal is expected to be associated with an increased likelihood of disidentification.

Moderation by Centrality and Private Regard

Individual differences in ERI are considered to moderate the effects of stereotype appraisal (Schmader, Johns, & Forbes, 2008). The current study considers two dimensions of ERI: centrality and private regard. Centrality is defined as the extent to which race/ ethnicity is central to one’s overall identity (Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton, & Smith, 1997). Private regard refers to how positively one feels about his or her ethnic/racial group membership (Sellers et al., 1997). Although there is little research exploring how centrality and private regard might moderate the association between stereotype appraisal and disidentification, researchers have suggested that it is an important avenue for exploration (Arndt et al., 2002): “the centrality of the group identity that is under threat may be an important moderator of whether one’s group identity is defended (or justified) or denied” (p. 40). How centrality will influence the association between stereotype appraisal and disidentification is less clear. For example, Ellemers, Spears, and Doosje (1999) have suggested that disidentification may be stronger for individuals with low centrality who are faced with a negative stereotype about an ingroup. In this case, if an individual is being targeted by a stereotype based on group membership that is of little relevance to their identity, she or he may reject that identity more staunchly. On the other hand, others have proposed that the more invested an individual is in an ERI, the more strongly that individual will embrace and defend that identity (Doosje, Ellemers, & Spears, 1995; Schmader, 2002). If one’s membership in an ethnic/racial group is so central that it threatens the foundation of one’s identity, disidentification may be the only way to preserve self-esteem. Similar observations can be made for how private regard might moderate individual’s responses to threats imposed by stereotypes. The current study sought to test these equally plausible, yet competing, hypotheses, along with considering the possibility that centrality and private regard might interact to produce jointly muted or amplified effects.

Associations Between Disidentification and Psychological Mood

The current review discusses how disidentification may be associated with psychological mood, and whether either of these associations may be influenced by individual differences in centrality and private regard. Consistent with existing literature, stereotype appraisal was expected to be associated with lower psychological mood (Schmader & Beilock, 2011). Many scholars have proposed that, with the development of a strong ERI, minorities are well-equipped with protective armor to maintain self-esteem in the face of social group threats (Crocker, Luhtanen, Blaine, & Broadnax, 1994). As such, if disidentification serves a protective function for individuals with strong ERI (i.e., centrality and private regard), it should buffer the negative effects of stereotype appraisal. Again, theory and research also lend themselves to the opposite prediction. For example, the more invested an individual is in an ERI, the more strongly that individual will be affected by threats to that identity (Doosje et al., 1995; Schmader, 2002). The current study explored both of these possibilities. Further, whatever the direction of these effects, it was expected that they would be amplified for young adults reporting high levels of centrality and private regard.

The Current Study

Borrowing from the stress and coping literature, the current study drew from theoretical frameworks put forth by Bolger and Zuckerman (1995). Specifically, Bolger and Zuckerman suggested that individual differences in neuroticism may influence both the extent to which individuals experience conflicts and the effectiveness of their coping strategies. Analogously, the present study suggests that individual differences in ERI may influence the extent to which individuals engage in disidentification when they feel they have been influenced by a racial/ethnic stereotype and the extent to which disidentification is effective as a coping strategy.

Using these two study goals, the current study sought to explore the associations between stereotype appraisal, disidentification, and psychological mood in a sample of ethnically and racially diverse young adults. Namely, the first study goal included examining how stereotype appraisal is related to disidentification. Existing research has suggested that a positive association should be present. Whether and how this association will differ for young adults depending on ERI centrality and private regard is unclear. The second study goal examined the associations between disidentification and mood. Based on existing research, it was hypothesized that disidentification would be associated with lower psychological mood, and that these associations would differ according to young adults’ level of centrality and private regard.

Although the above set of analyses provide the necessary analytical framework for testing statistical mediation (i.e., disidentification mediates the association between stereotype appraisal and mood) and Bolger and Zuckerman (1995) did provide for such a possibility in their differential exposure model, SIT does not provide a theoretical reason for doing so. One of the primary requirements for testing statistical mediation is a theoretical reason to predict a chain of causal processes that provide an explanatory mechanism for an observed effect (Krull & MacKinnon, 2001; Zhang, Zyphur, & Preacher, 2009). In this case, one would have to expect that the reason stereotype appraisal is related to mood is because of an association with disidentification. Although this hypothesis was not predicted by the present research, it is has been included here in an exploratory interest.

Method

Participants

Data were collected from 129 self-identified minority students (Mage = 20.63 years, SD = 1.49) at two private and predominantly White universities in the northeastern United States. All 4 years were roughly equally represented in the sample (23% freshman, 20% sophomore, 20% junior, 23% senior, and 14% missing or other). The largest racial/pan-ethnic group included Asian students (32%), followed closely by African/African American students (27%), and Hispanic/Latino (17%), while the remaining 24% were other, bi-/multiracial, or missing. Females were overrepresented in the sample (62%), with 25% male, and 13% missing.

Procedure

Participants were recruited via the psychology subject pool, through email, and posting flyers on campus advertising a study about daily life experiences; however, only three participants were recruited via flyers. Participants were asked to complete 21 days of daily diaries. To incentivize compliance across the 21 days (i.e., in order to receive full compensation [$75]), participants had to complete at least 60% (13 of 21 days) of the study. All participants met this criterion. All respondents to the flyers were directed to a brief, online, prescreening survey. The purpose of the prescreening survey was to select a sample of minority participants; therefore, only non-White students were invited to participate in the study.

Invited participants met a researcher in a research laboratory in groups of 1–5 for an orientation session. During this session, participants were instructed how to complete their diaries online each night before going to sleep, beginning on the night of the orientation. Participants also completed a demographic survey online, including questions about their ERI. After 21 days completing nightly diaries, on the last night, participants were also instructed to complete a final demographic survey that included questions about their ERI.

Measures

Daily-level stereotype appraisal

To assess the extent to which participants felt that they were affected by a stereotype each day, the following item was administered: “Please think about how much you agree or disagree with each statement TODAY … stereotypes about my ethnic/racial group did not affect me personally today” on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). So that higher scores indicated a stronger endorsement of stereotypes affecting a young adult each day, this item was reversed scored.

Daily-level ethnic/racial disidentification

Daily disidentification was assessed with two items: “I did NOT feel like a member of my ethnic/racial group today” and the reverse-coded item “I felt like a member of my ethnic/racial group today,” scored on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely) (r = .53).

Daily-level mood

Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which four items (i.e., happy, calm, joyful, and excited) described their positive mood that day, scored on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely) (α = .81). In addition, participants indicated their negative mood using 12 items (i.e., anxious, sad, nervous, hopeless, discourages, on edge, blue, disappointed, dissatisfied, disillusioned, frustrated, and defeated; α = .98).

Person-level ERI centrality and private regard

The Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (Sellers et al., 1997) was adapted for use with a multiethnic population by replacing “Black” in the original scale with “my race/ethnicity.” In particular, centrality includes seven items and measures the relative importance of ethnicity to one’s overall identity. For example: “My race/ethnicity is an important reflection of who I am.” The response scale ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) (α = .85). Private regard includes seven items and taps into an individual’s feeling about his or her ethnic/racial group membership. For example: “I am happy that I am a member of my ethnic/racial group” (α = .75). Because ERI was measured at the beginning and end of the 21-day study, differences were explored. There were no significant differences in centrality, t(103) = 0.19, ns, or private regard, t(103) = 1.07, ns, at the beginning or end of the study.

Results

Data Analyses Overview

Descriptive statistics and correlations between the study variables were examined (see Table 1). Centrality and private regard at the person level were compared with the mean of the daily variables. Appraisal of ethnic/racial stereotypes was negatively associated with positive mood, but was positively associated with negative mood and centrality. Disidentification was positively associated with negative mood. Positive and negative mood were negatively correlated. Negative mood negatively correlated with private regard. Finally, the two person-level measures, centrality and private regard, were positively correlated. In addition, possible group-level differences (i.e., Asian, Black, Hispanic, and other) in stereotype appraisal were explored with a one-way analysis of variance; no significant differences, F(3, 115) = 1.00, ns, were observed.

Table 1.

Correlations Among Key Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mean of daily ethnic/racial stereotype | — | .15 | −.30** | .42** | .23* | −.16 | 2.74 | 0.89 |

| 2. Mean of daily disidentification | — | .08 | .26** | −.01 | −.18 | 2.77 | 1.34 | |

| 3. Mean of daily positive mood | — | −.26** | .15 | .18 | 4.18 | 1.21 | ||

| 4. Mean of daily negative mood | — | −.04 | −.40** | 2.19 | 1.18 | |||

| 5. Centrality | — | .34** | 4.42 | 1.13 | ||||

| 6. Private regard | — | 5.65 | 0.73 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

The primary study hypotheses were tested using hierarchical linear models (HLMs; Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992), which accounts for how days are nested within young adults. HLM allows for simultaneous analyses at more than one level. In this case, days were considered at Level 1 and young adult characteristics were modeled at Level 2. In all analyses, day of the study (1–21) and day type (weekday vs. weekend) were adjusted in the Level 1 model. Possible effects of gender (male vs. female) and race (Asian, Black, Hispanic, other) were adjusted in all models at Level 2; however, no significant effects were observed. For ease of presentation, these variables are omitted from the models presented here. Because data were collected at two universities, possible mean differences were examined before testing study hypotheses. There were no significant differences between the two schools on any study variables. In addition, models including and excluding school did not significantly differ; therefore, analyses are presented excluding the school variable.

To address the first goal of the study, an unconditional model to determine if there was significant variability in daily disidentification and stereotype appraisal was estimated. Results suggested that there was significant variation in disidentification, χ2(100) = 717.03, p < .01, and stereotype appraisal, χ2(100) = 323.32, p < .01; therefore, the daily association between ethnic/racial stereotype appraisal and disidentification was explored next (see Equation 1).

Level 1 (Daily level):

| (1) |

Contrary to hypotheses, the results suggested that being affected by an ethnic/racial stereotype was not associated with disidentification (B = −0.03, SE = 0.05, ns). Next, person-level differences in centrality, private regard, and their interaction were included at Level 2 (Equation 2). Person-level variables were included as moderators of the intercept (P0) and the slope for the effect of an ethnic/racial stereotype (P3).

Level 2 (Person level):

| (2) |

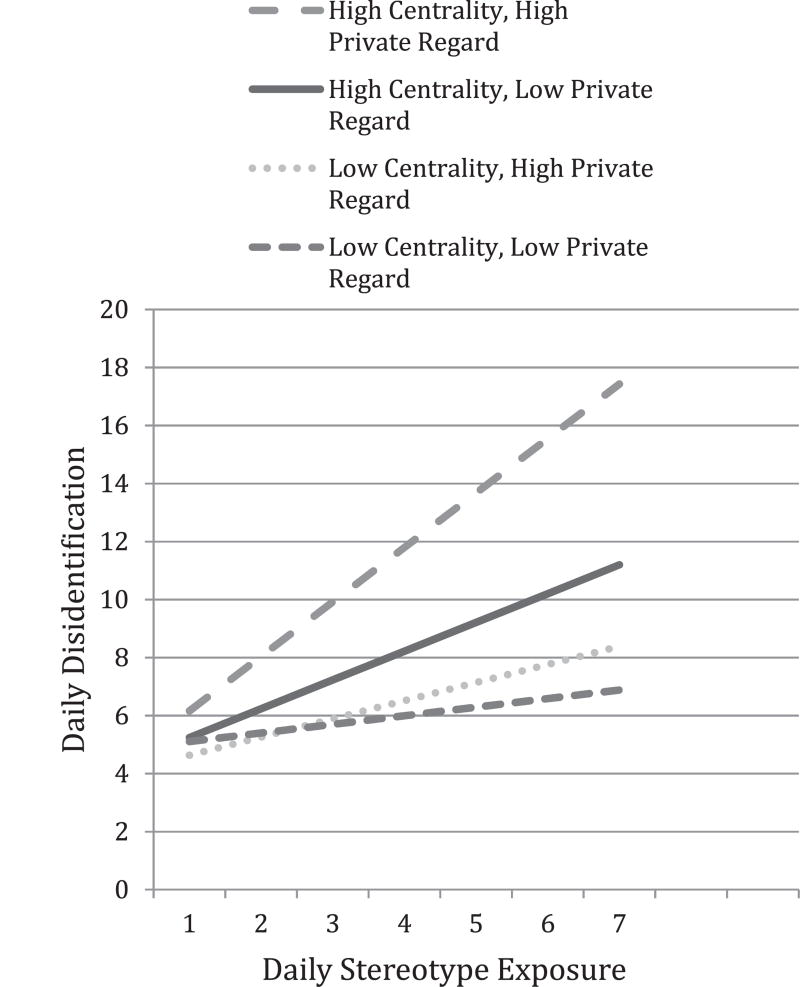

Results indicated that the Centrality × Private Regard interaction moderated the association between stereotype appraisal and disidentification (see Table 2 and Figure 1). Simple slope tests found that individuals with high centrality and high private regard reported the steepest increase in disidentification on days on which they reported feeling exposed to an ethnic/racial stereotype about their group (t = 2.05, p < .05; Shacham, 2009). For individuals with high levels of centrality but low levels of private regard, there was also a significant increase in disidentification correlated with daily stereotype appraisal (t = 2.14, p < .03). The associations between stereotype appraisal and disidentification for low centrality individuals were not significant. This model explained 18% of the variance in daily disidentification.

Table 2.

HLM Estimates of Ethnic/Racial Disidentification as Predicted Feeling Affected by Ethnic/Racial Stereotype, Moderated by Centrality and Private Regard

| Variable names | Variables | B | SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily-level ethnic/racial disidentification | B00, P00 | 6.68*** | 0.52 |

| Centrality | B01, P01 | −0.37*** | 0.08 |

| Private regard | B02, P02 | −0.39*** | 0.10 |

| Centrality × Private Regard | B03, P03 | 0.06 | 0.11 |

| Day of study | B10, P10 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Weekday/weekend | B20, P20 | −0.03 | 0.05 |

| Affected by ethnic/racial stereotype | B30, P30 | −0.12 | 0.13 |

| Centrality | B31, P31 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Private regard | B32, P32 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Centrality × Private Regard | B33, P33 | 0.04* | 0.02 |

Note. HLM = hierarchical linear model.

p < .05.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

The daily association between ethnic/racial stereotype exposure and disidentification: Individual differences by ethnic/racial identity centrality and private regard.

To address the second goal, the unconditional model for positive and negative mood was estimated. The results suggested that both varied significantly, positive: χ2(100) = 518.83, p < .01; negative: χ2(100) = 843.12, p < .01. Next, the daily association between disidentification and mood, with a separate equation for positive and negative mood (Equation 3), was explored. For each of the equations, the effect of the other mood variable and appraisal of ethnic/racial stereotype was adjusted. The results suggested that disidentification was associated with more negative mood (B = 0.06, SE = 0.03, p < .05) and marginally associated with positive mood (B = −0.07, SE = 0.04, p = .06). Next, whether individual differences in centrality and private regard might influence the above daily-level association was estimated. Person-level variables were included as moderators of the intercept (P0) and the slope for the effect of disidentification (P4). For ease of presentation, only the positive mood equation is shown below.

Level 1 (Daily level):

| (3) |

Level 2 (Person level):

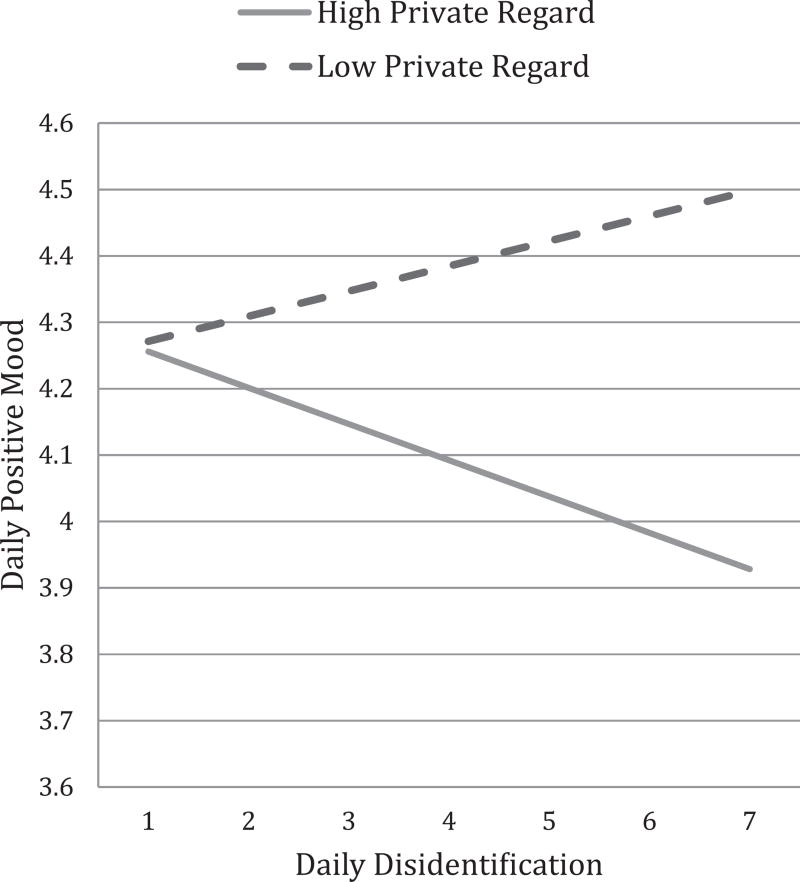

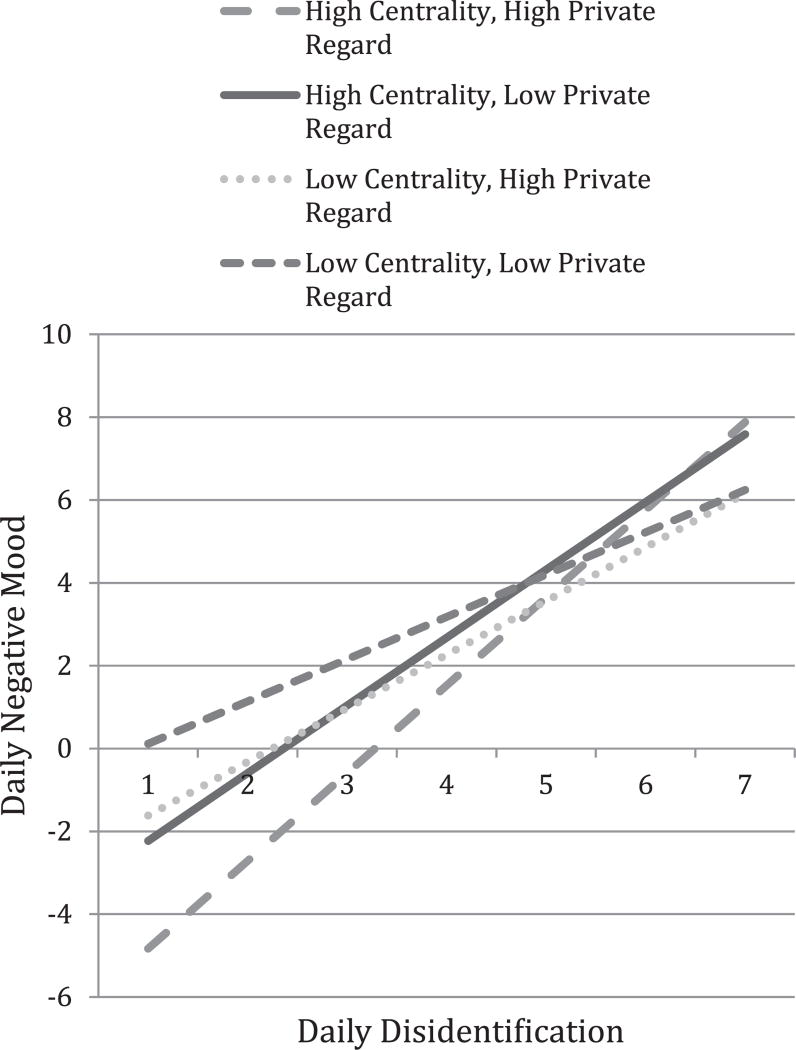

As shown in Table 3, the association between disidentification and positive mood (P4) was moderated by private regard, whereas the association between disidentification and negative mood was moderated by the Centrality × Private Regard interaction (B43). Simple slope analyses revealed that individuals with high private regard reported less positive mood on days on which they also reported disidentification, whereas individuals with low private regard reported the opposite pattern (Shacham, 2009). Although the interaction was significant, due to the crossover nature of the slopes, the simple slopes did not differ significantly from zero (see Figure 2). The proportion of total variance explained by this model was 18%. With respect to negative mood, there were differences in negative mood by centrality, private regard, and their interaction (see Figure 3). Simple slope tests found all combinations of centrality and private regard to have slopes that differed significantly from zero (Shacham, 2009). Specifically, all individuals reported an increase in negative mood on days on which they also reported disidentification, with high centrality and high private regard individuals reporting the steepest association (t = 2.11, p < .05). Individuals with high centrality and low private regard also reported an increase in negative mood on days on which they disidentified with their group (t = 2.01, p < .05). Finally, individuals reporting low centrality reported similar positive associations between disidentification and negative mood, regardless of levels of private regard. The proportion of total variance explained by this model was 39%.

Table 3.

HLM Estimates of Positive and Negative Mood as Predicted Feeling Affected by Disidentification, Moderated by Centrality and Private Regard

| Positive | Negative | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Variable names | Variables | B | SE | B | SE |

| Daily-level private regard | B00, P00 | 3.99*** | 0.82 | 4.78*** | 0.66 |

| Centrality | B01, P01 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.20* | 0.10 |

| Private regard | B02, P02 | 0.05 | 0.13 | −0.28** | 0.10 |

| Centrality × Private Regard | B03, P03 | −0.14 | 0.14 | −0.31** | 0.11 |

| Day of study | B10, P10 | −0.03*** | 0.01 | −0.02*** | 0.00 |

| Weekday/weekend | B20, P20 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.11** | 0.04 |

| Positive/negative mood | B30, P30 | −0.47*** | 0.04 | −0.37*** | 0.03 |

| Ethnic/racial disidentification | B40, P40 | 0.33* | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.17 |

| Centrality | B41, P41 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| Private regard | B42, P42 | −0.06* | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| Centrality × Private Regard | B43, P43 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06* | 0.03 |

| Affected by ethnic/racial stereotype | B50, P50 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

Note. HLM = hierarchical linear model.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 2.

The daily association between disidentification and positive mood: Individual differences by ethnic/racial identity centrality and private regard.

Figure 3.

The daily association between disidentification and negative mood: Individual differences by ethnic/racial identity centrality and private regard

Finally, exploratory analyses examined the possibility that disidentification might mediate the effect of stereotype appraisal on mood. As such, the effect of stereotype appraisal today on mood the next day was explored. Stereotype appraisal was not associated with positive mood (B = 0.00, SE = 0.02, p < .05) or negative mood (B = 0.01, SE = 0.02, p < .05), therefore, further tests of mediation were not conducted.

Discussion

The current study is the first to my knowledge to explore the phenomenon of disidentification using daily diary methods to capture young adults in their naturally occurring contexts and interactions. The study makes a unique contribution to our understanding of ERI distancing processes among young adults who are presumably grappling with ERI construction. Specifically, the study explored how the appraisal of ethnic/racial stereotypes about one’s group may be related to decisions to disidentify with one’s ERI. Guided by SIT, the study also explored the implications of disidentification on psychological feelings.

As the first goal of this study, the effects of ethnic/racial stereotype appraisal on daily feelings of ERI disidentification were explored. Based on existing research and theory (Hogg & Abrams, 1988; Hogg & Terry, 2000), it was expected that stereotype appraisal would be negatively related to disidentification. However, the data did not support this hypothesis. Instead, similar to theories about stereotype threat (Schmader et al., 2008), the effect of stereotypes depended on individual differences in centrality and private regard. Namely, individuals reporting high levels of centrality reported the strongest positive association between stereotype appraisal and disidentification, with those reporting high levels of private regard exhibiting the strongest associations. That is, individuals who reported that ERI was both a central and highly regarded aspect of the self were most likely to disidentify from their ERI on days on which they reported feeling affected by an ethnic/racial stereotype that day. This observation is consistent with existing theory and research linking disidentification tendencies with a psychological need to create distance from a threatened identity (Arndt et al., 2002; Driedger, 1976; Elsbach & Bhattacharya, 2001; Rothman, 1960). What the current study adds to this literature is the importance of considering individual differences in ERI because the tendency to disidentify is not uniform across levels of centrality or private regard. When individuals are exposed to stereotypes related to a core component of their identity, they are more likely to disidentify with that identity. As many have observed, this is likely a self-preservation technique, particularly because the association seems strongest for individuals who also report high private regard.

Finally, to address the second goal of this study, the associations between disidentification with ERI and positive and negative mood were explored. In general, disidentification was associated with more negative mood and marginally associated with less positive mood. However, as with the association between stereotypes and disidentification, individual differences in ERI centrality and private regard were apparent. Namely, private regard resulted in opposite associations between disidentification and positive mood where high levels were associated with a negative association and low levels were associated with a positive association. Controlling for stereotype appraisal, on days on which individuals with high private regard disidentified with their group, they also reported less positive mood. In contrast, on days on which individuals with low private regard disidentified, they reported increased positive mood. Because the data were not longitudinal, it is unclear whether the reason individuals were able to maintain a positive sense of group regard is because they chose to disidentify from their identity. However, this hypothesis would be supported by SIT. For individuals reporting low private regard, it seems that disidentifying is associated with an increase in positive mood, suggesting that their lack of attachment to their ERI may mean that their daily mood is anchored in other, more positively regarded social identities.

Looking at negative mood, although in general there was a positive association between disidentification and negative mood, again the importance of individual differences in centrality and private regard were apparent. As in previous analyses, one sees the most striking associations for individuals reporting high centrality and high private regard. For such individuals, controlling for stereotype appraisal, on days on which disidentification was endorsed more strongly, the more negative mood was reported. This suggests that disidentification comes at a psychological cost and that those who are most invested in the disidentified identity pay the highest price. This pattern seems to run counter to what one might expect based on the central tenants of SIT; however, SIT was formulated to discuss person-level associations between identity and self-regard and does not provide hypotheses about day-to-day associations. Therefore, it is still possible that, although the same-day associations between disidentification and negative mood are positive, over time, disidentification may still be associated with better self-regard in the long run. This question is an empirical one, and aside from the current study, the existing literature on disidentification has not explored its psychological implications.

Adopting a general stress and coping framework (Bolger & Zuckerman, 1995), the current study also tested the possibility that disidentification might mediate the link between stereotype appraisal and outcomes. As expected based on existing theory and research, however, this exploratory hypothesis was not supported by the data. Instead, it seems that ERI is associated with differential reactivity to stereotype appraisal and the effectiveness of disidentification as a coping strategy.

Study Limitations

Although the current study addressed an important gap in the current literature, it is not without limitations. For one, the current operationalization of stereotype appraisal included only a single item and did not differentiate between positive and negative stereotypes. One might expect differences in the influence of stereotype depending on its valence. On the other hand, it is plausible that, regardless of valence, stereotypes have a universally negative effect by virtue of highlighting socially imposed group uniformity at the expense of individual differences—a possibility that future research should explore. On a related note, the perpetrator of the stereotype was not identified in the current study. It seems possible that ingroup versus outgroup perpetrators may be led to different associations with disidentification and psychological mood. Importantly, the current study raises interesting and important avenues for future investigations. Developmentally, it would be important for future research to explore whether the repeated pairing of stereotype appraisal and psychological mood results in person-level differences in private regard over time. Some scholars have suggested that young individuals internalize negative ingroup images over time (Pinel, 1999) and exploring these associations would empirically test such hypotheses. As well, it would be fruitful for future research to explore whether there are individual differences in young adults’ tendency to disidentify and if these daily-level experiences result in lower levels of person-level centrality over time.

Conclusion

Limitations notwithstanding, the current study represents a contribution to the study of how young adults of color navigate everyday race-related experiences. Consistent with experimental research among middle-aged and older adults, the study observed that young adults will opt to distance themselves psychologically from their ERI when exposed to ethnic/racial stereotypes. Contrary to theory, stereotype appraisal was not generally associated with disidentification. Echoing existing research on ERI, the current study highlights the importance of individual differences; namely, the extent to which young adults claim ethnicity as central to their self-concept and their feelings about group membership. Taken together, the current study sheds light on the complex dynamics that contribute to the development of an ERI and suggests that disidentification (although currently understudied) may be part of the normative process of identity development. In closing, the current study points to the importance of considering disidentification processes in addition to identity affirmation in order to create a more well-rounded literature on the importance of ERI in the everyday lives of young adults in the United States.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child and Human Development (5R01HD055436-02) and National Science Foundation (BCS-0742390). The author would like to thank J. Nicole Shelton, who served as PI on both grants, for comments on previous versions of this manuscript.

References

- Abrams D, Hogg M. Comments on the motivational status of self-esteem in social identity and intergroup discrimination. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1988;18:317–334. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420180403. [Google Scholar]

- Armenta BE. Stereotype boost and stereotype threat effects: The moderating role of ethnic identification. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:94–98. doi: 10.1037/a0017564. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0017564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt J, Greenberg J, Schimel J, Pyszczynski T, Solomon S. To belong or not to belong, that is the question: Terror management and identification with gender and ethnicity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:26–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.1.26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore RD, Deaux K, McLaughlin-Volpe T. An organizing framework for collective identity: Articulation and significance of multidimensionality. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:80–114. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizman A, Yinon Y. Engaging in distancing tactics among sport fans: Effects on self-esteem and emotional responses. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2002;142:381–392. doi: 10.1080/00224540209603906. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00224540209603906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Zuckerman A. A framework for studying personality in the stress process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:890–902. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.890. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cheryan S, Bodenhausen GV. When positive stereotypes threaten intellectual performance: The psychological hazards of “model minority” status. Psychological Science. 2000;11:399–402. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00277. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Luhtanen R. Collective self-esteem and ingroup bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:60–67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.1.60. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Luhtanen R, Blaine B, Broadnax S. Collective self-esteem and psychological well-being among White, Black, and Asian college students. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1994;20:503–513. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167294205007. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B, Steele CM. Social stigma. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The handbook of social psychology. 4. Vol. 2. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 504–553. [Google Scholar]

- Doosje B, Ellemers N, Spears R. Perceived intragroup variability as a function of group status and identification. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1995;31:410–436. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jesp.1995.1018. [Google Scholar]

- Driedger L. Ethnic self-identity: A comparison of ingroup evaluations. Sociometry. 1976;39:131–141. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2786213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers N, Spears R, Doosje B. Social identity. Oxford, England: Blackwell; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Elsbach KD, Bhattacharya CB. Defining who you are by what you’re not: Organizational disidentification and the National Rifle Association. Organization Science. 2001;12:393–413. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12.4.393.10638. [Google Scholar]

- Frable DE, Platt L, Hoey S. Concealable stigmas and positive self-perceptions: Feeling better around similar others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:909–922. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.4.909. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.4.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodson G, Esses VM. Distancing oneself from negative attributes and the personal/group discrimination discrepancy. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2002;38:500–507. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1031(02)00012-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg MA, Abrams D. Social identifications: A social psychology of intergroup relations and group processes. Florence, KY: Taylor & Frances/Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg MA, Terry DJ. Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. The Academy of Management Review. 2000;25:121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg MA, Terry DJ, White KM. A tale of two theories: A critical comparison of identity theory with social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1995;58:255–269. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2787127. [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Yip T, Fuligni AJ. Multiple social identities and adjustment in young adults from ethnically diverse backgrounds. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2008;18:643–670. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2008.00575.x. [Google Scholar]

- Krull JL, MacKinnon DP. Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2001;36:249–277. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peetz J, Gunn GR, Wilson AE. Crimes of the past: Defensive temporal distancing in the face of past in-group wrongdoing. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:598–611. doi: 10.1177/0146167210364850. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167210364850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Romero I, Nava M, Huang D. The role of language, parents, and peers in ethnic identity among adolescents in immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2001;30:135–153. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1010389607319. [Google Scholar]

- Pinel EC. Stigma consciousness: The psychological legacy of social stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:114–128. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.1.114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid SA, Hogg MA. Uncertainty reduction, self-enhancement, and ingroup identification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:804–817. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271708. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman J. In-group identification and out-group association: A theoretical and experimental study. Journal of Jewish Communal Service. 1960;37:81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin M, Hewstone M. Social identity theory’s self-esteem hypothesis: A review and some suggestions for clarification. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2:40–62. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmader T. Gender identification moderates stereotype threat effects on women’s math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2002;38:194–201. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jesp.2001.1500. [Google Scholar]

- Schmader T, Beilock SL. An integration of processes that underlie stereotype threat. In: Inzlicht M, Schmader T, editors. Stereotype threat: Theory, process, and application. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 34–50. [Google Scholar]

- Schmader T, Johns M, Forbes C. An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance. Psychological Review. 2008;115:336–356. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.336. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM, Shelton JN, Smith MA. Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: A preliminary investigation of reliability and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:805–815. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.4.805. [Google Scholar]

- Shacham R. A utility for exploring HLM 2 and 3 way interactions [Computer software] 2009 Available at http://www.shacham.biz/HLM_int/index.htm.

- Shih M, Pittinsky TL, Ambady N. Stereotype susceptibility: Identity salience and shifts in quantitative performance. Psychological Science. 1999;10:80–83. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00371. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:797–811. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.797. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC, Hogg MA, Oakes PJ, Reicher SD, Wetherell MS. Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford, England: Blackwell; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ying YW, Lee PA, Tsai JL, Hung Y, Lin M, Wan CT. Asian American college students as model minorities: An examination of their overall competence. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2001;7:59–74. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.1.59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.7.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Zyphur MJ, Preacher K. Testing multilevel mediation using hierarchical linear models. Organizational Research Methods. 2009;12:695–719. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1094428108327450. [Google Scholar]