Abstract

Background—

Although HIV is associated with increased atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, it is unknown whether guidelines can identify HIV-infected adults who may benefit from statins. We compared the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and 2004 Adult Treatment Panel III recommendations in HIV-infected adults and evaluated associations with carotid artery intima-media thickness and plaque.

Methods and Results—

Carotid artery intima-media thickness was measured at baseline and 3 years later in 352 HIV-infected adults without clinical atherosclerotic CVD and not on statins. Plaque was defined as IMT >1.5 mm in any segment. At baseline, the median age was 43 (interquartile range, 39–49), 85% were men, 74% were on antiretroviral medication, and 50% had plaque. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines were more likely to recommend statins compared with the Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines, both overall (26% versus 14%; P<0.001), in those with plaque (32% versus 17%; P=0.0002), and in those without plaque (16% versus 7%; P=0.025). In multivariable analysis, older age, higher low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, pack per year of smoking, and history of opportunistic infection were associated with baseline plaque. Baseline IMT (hazard ratio, 1.18 per 10% increment; 95% confidence interval, 1.05–1.33; P=0.005) and plaque (hazard ratio, 2.06; 95% confidence interval, 1.02–4.08; P=0.037) were each associated with all-cause mortality, independent of traditional CVD risk factors.

Conclusions—

Although the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines recommended statins to a greater number of HIV-infected adults compared with the Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines, both failed to recommend therapy in the majority of HIV-affected adults with carotid plaque. Baseline carotid atherosclerosis but not atherosclerotic CVD risk scores was an independent predictor of mortality. HIV-specific guidelines that include detection of subclinical atherosclerosis may help to identify HIV-infected adults who are at increased atherosclerotic CVD risk and may be considered for statins.

Keywords: adult, atherosclerosis, carotid artery diseases, carotid intima-media thickness, HIV

A cornerstone of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk reduction, statin therapy has consistently lowered cardiovascular disease (CVD) events in multiple randomized controlled trials during the past 30 years.1 Cholesterol treatment guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) published in 2013 recommend moderate-to-high intensity statins for primary prevention in adults who have increased cardiac risk; defined as having a 10-year ASCVD risk score of ≥7.5% based on the ACC/AHA pooled cohort risk equation calculator.2 The ASCVD risk score is based on traditional CVD risk factors, such as the presence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and smoking history.

See Editorial by Grinspoon and Hoffmann

Since their release, these recommendations have created controversy surrounding the accuracy and appropriateness of applying the calculator to special populations, such as those with HIV. Although CVD mortality has decreased for the general population in the United States during the past decade, partly because of the treatment of modifiable risk factors, such as hyperlipidemia, the HIV-infected population has seen an increase in CVD mortality during the same period.3 Although the increased cardiac risk seen in HIV-infected adults is partly attributed to traditional factors, such as smoking, a growing body of evidence has shown that there are HIV-specific issues, such as antiretroviral therapy-related dyslipidemia and chronic inflammation, that independently contribute to the elevated risk.4

Given the potential influence of nontraditional factors on CVD risk in HIV-infected adults, applying the ACC/AHA pooled cohort risk equation calculator to HIV-infected adults may underestimate their CVD risk and subsequently fail to recommend statin therapy. The ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines suggest using additional risk-assessment tools, such as noninvasive atherosclerosis imaging, to help guide statin treatment decisions in special populations. Carotid atherosclerosis by ultrasound has been shown to predict future ASCVD events and can be used as a surrogate measure to assess the vascular benefits of statin therapy.5 Beyond using traditional risk factors, the detection of carotid atherosclerosis by ultrasound may help identify a subset of HIV-infected adults who are at increased CVD risk and may benefit from treatment. The aim of our current study is to assess the application of the ACC/AHA cholesterol treatment guidelines on a cohort of HIV-infected adults who have had an evaluation of carotid atherosclerosis by ultrasound.

Patients and Methods

Participants

Study participants were followed at San Francisco General Hospital and San Francisco Veteran’s Affairs Medical Center as part of the SCOPE (Studies of the Consequences of the Protease Inhibitor Era) cohort—a longitudinal observational cohort of HIV-infected individuals. Participants with a history of established ASCVD, including coronary heart disease, cerebral vascular disease, or peripheral vascular disease or a history of prior and current statin use, were excluded from the study. The study follow-up period began in 2001, and participants were seen annually. The University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research approved this study, and all participants provided written informed consent (NCT01519141). For all-cause mortality, participants were followed through January 2015 or until the time of death as determined by the National Death Index. Two independent physicians adjudicated cardiovascular death using patient International Classification of Diseases-Ninth Revision codes provided by the National Death Index. To be considered a cardiovascular death, patients were required to have an International Classification of Diseases-Ninth Revision code related to cardiovascular pathology in ≥1 of the first 3 International Classification of Diseases-Ninth Revision codes reported on the death document.

Clinical and Laboratory Assessment

Interviews and structured questionnaires were given to all participants at the time of enrollment covering sociodemographic characteristics, CVD risk factors, HIV disease history, medications, and health-related behaviors, including drug use. Fasting blood work was drawn to measure serum total cholesterol, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was calculated using Friedewald formula6 except for participants with triglycerides ≥400 or <40 mg/dL, where it was measured directly. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels were measured using a high-sensitivity assay (Dade Behring, Deerfield, IL).

ASCVD Risk Assessment and Statin Recommendation

Statin recommendation for primary prevention was assessed for each participant using the 2004 Adult Treatment Panel (ATP) III and 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol treatment guidelines.2,7 Using ATP III, participants were recommended for statin therapy if they were considered to have (1) diabetes mellitus or a 10-year Framingham risk score (FRS) >20% and LDL ≥100 mg/dL, (2) 2+ CVD risk factors or 10-year FRS 10% to 20% and LDL ≥130 mg/dL, (3) 2+ CVD risk factors or 10-year FRS <10% and LDL ≥160 mg/dL, or (4) 0 to 1 CVD risk factors with LDL ≥190 mg/dL. FRS was calculated using the following variables: age, sex, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, smoking status, systolic blood pressure, and currently on high blood pressure medications.7 Risk factors included hypertension, smoking, low HDL cholesterol (<40 mg/dL), family history of premature coronary heart disease (coronary heart disease in men first-degree relative <55 years of age; coronary heart disease in women first degree-relative <65 years of age), and age (men ≥45 years; women ≥55 years). Using ACC/AHA guidelines, statins were recommended for participants if they were (1) ≥21 years of age with LDL levels ≥190 mg/dL, (2) 40 to 75 years old with diabetes mellitus with LDL cholesterol 70 to 189 mg/dL, or (3) 40 to 75 years of age with ASCVD risk score of ≥7.5% using the ACC/AHA risk calculator. ACC/AHA risk calculator included the following variables: age, sex, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, smoker, systolic blood pressure, current treatment with blood pressure medications, diabetes mellitus, and race (white, black, or other).2

Carotid Atherosclerosis Assessment

Carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT) was assessed using the GE Vivid 7 system and a 10-MHz linear array probe and measured in 12 segments, including the near and far wall of the common carotid artery, bifurcation, and internal carotid artery of both the right and left carotid arteries, according to the standard protocol from the ARIC Study (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study)8 and as previously described from our group.9,10 All measurements were performed by one experienced technician on digital images using a manual caliper. The technician was blinded with respect to regard to patient history and clinical characteristics. Carotid plaque was defined as a focal area with IMT >1.5 mm in any segment. Repeat scans and measurements were performed with a noted variation coefficient—the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean—of 3.4% and intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.98.

Statistical Analysis

We summarized the continuous variables using median and interquartile range, and categorical variables using percentage, by statin recommendation based on ATP III and ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines. We tested the differences by statin recommendation using Student t test for normally distributed continuous variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for the rest. For categorical variables, χ2 test was used. McNemar test, which examines the symmetry of a 2×2 table was used to compare whether the recommendation for statin therapy using the 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines agreed with the recommendation using 2004 ATP III guidelines. χ2 test was also used to compare statin recommendation for each guideline (ATP III and ACC/AHA) based on the presence or absence of carotid plaque, and Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test was used to compare statin recommendation for each guideline based on ordinal level of CIMT and its progression. We used ordinary least square regression to model the association of the ATP III Framingham and ACC/AHA ASCVD risk scores, as well as covariates with baseline CIMT, and linear mixed model with random intercept to model the association with CIMT progression. Additionally, we used Poisson regression models to estimate prevalence ratios (PRs) of plaque at baseline and plaque progression at follow-up and examine the association with baseline plaque and progression of plaque. A robust variance estimator was applied to adjust for potential overdispersion in the models. In all multivariable models, we adjusted for demographic factors (age, race, and sex). Cox proportional hazard models were constructed to estimate the hazard ratio and examine the association with all-cause mortality controlling for demographics and significant covariates found in unadjusted models. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4.

Results

Participant Characteristics

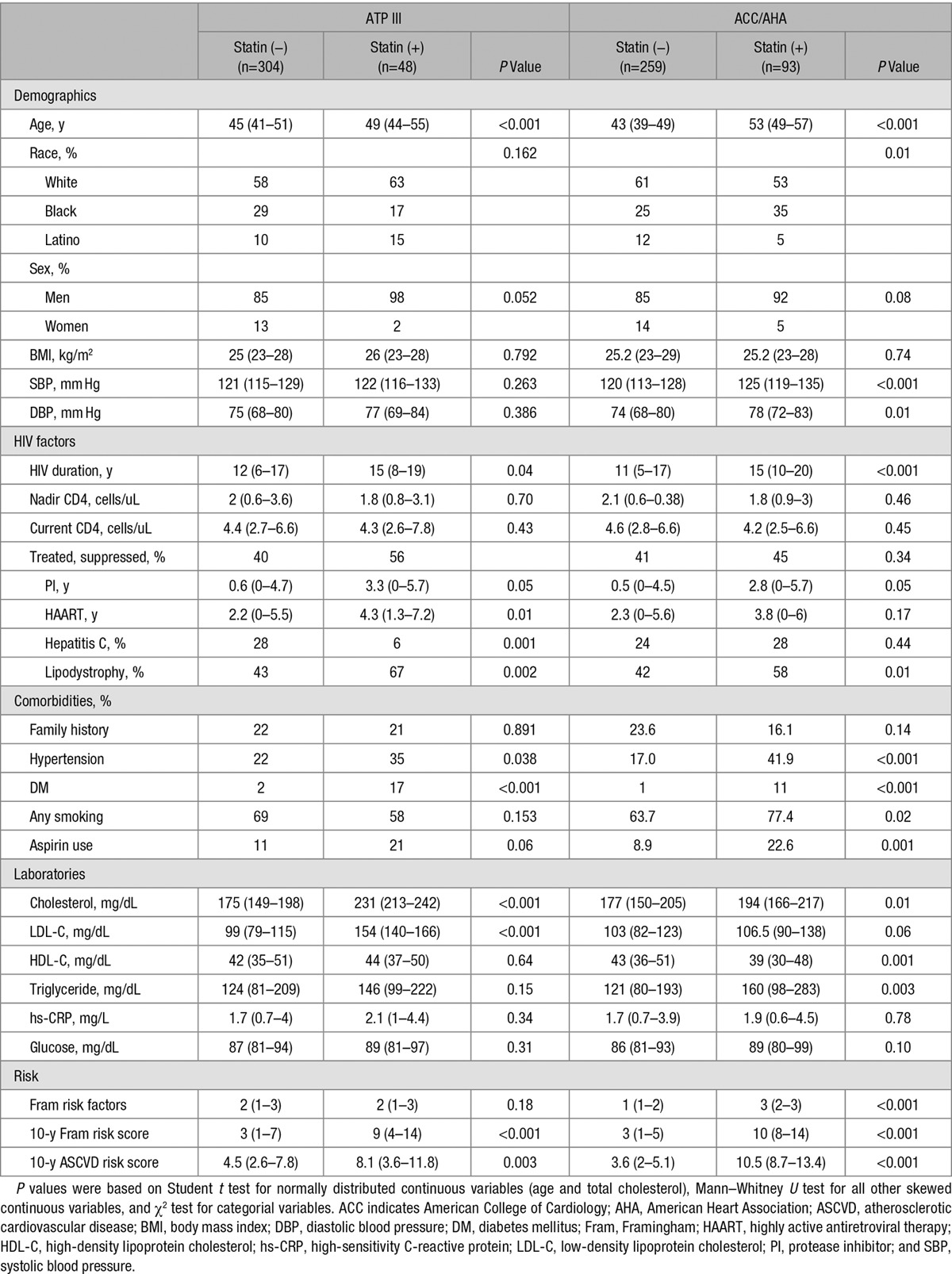

The baseline characteristics of the 352 HIV-infected participants in our study are shown in Table 1 stratified by whether statin therapy was recommended by the ATP III and ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines. Under both ATP III and ACC/AHA guidelines, more HIV-infected adults were not recommended for statin therapy (304 versus 48 for ATP III and 259 versus 93 for ACC/AHA). For the ACC/AHA guidelines, HIV-infected participants who were recommended for statin therapy were older than those not recommended for statins (median, 53 versus 43 years) with more participants being black and fewer being white. Participants recommended for statin therapy also had higher systolic blood pressure (125 versus 120 mm Hg), longer duration of HIV infection (15 versus 11 years), longer exposure to protease inhibitors (2.8 versus 0.5 years), and more evidence of lipodystrophy (58% versus 42%). Comorbidities and traditional risk factors were more common in those recommended for statin therapy, such as history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cigarette smoking. Total cholesterol and triglycerides were higher, and HDL cholesterol was lower in those recommended for statin therapy. On average, those recommended for statin therapy had higher number of Framingham risk factors, higher 10-year FRS, and higher 10-year ASCVD risk score. Similar baseline characteristic differences were noted when comparing statin recommendation for ATP III. Mean LDL cholesterol was higher in participants recommended for statin using ATP III, but difference in LDL cholesterol between statin recommendation groups was not observed using ACC/AHA guidelines. Death data were ascertained using Social Security Death Index and National Death Index registries. In the 13.5 years of follow-up, 47 deaths occurred; of these, 2 were CVD, 11 because of HIV-related infections, 11 because of cancer, 6 because of liver or renal disease, 5 because of recreational drug overdose, 2 because of physical assault, 2 because of respiratory disease, and 8 were unknown.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics (Median [Interquartile Range] or Percentage) of HIV-Infected Adults Stratified by Statin Recommendation Based on ATP III and ACC/AHA Cholesterol Guidelines

CIMT Characteristics at Baseline and Follow-Up

The median IMT at baseline was 0.85 mm (interquartile range, 0.72–1.04 mm), and 230 subjects (65.3%) had evidence of carotid plaque. The median duration of follow-up was 3.6 years. At follow-up, median IMT progression was 0.052 mm per year (interquartile range, 0.025–0.095 mm per year), and 71 subjects (58.2%), who did not have plaque at baseline, developed plaque.

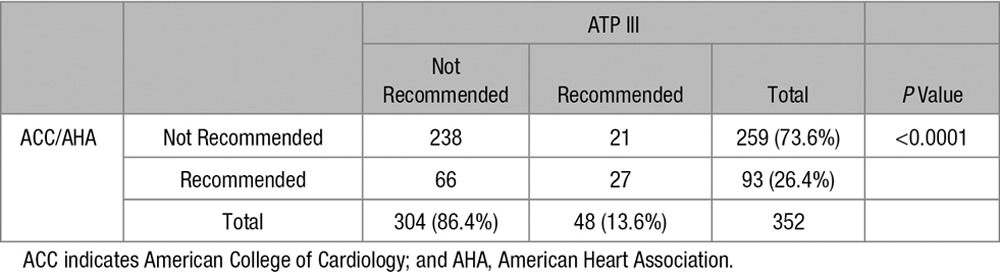

Statin Recommendations by Guidelines

Using the ACC/AHA guidelines, 26.4% of our overall HIV-infected population would be recommended statins as compared with 13.6% using the ATP III guidelines (P<0.0001; Table 2). Among subjects without evidence of carotid plaque, 15.6% would be recommended for statin therapy using ACC/AHA guidelines as compared with 6.6% using ATP III guidelines (P=0.025; Figure 1). Among subjects with evidence of carotid plaque, 32.2% of subjects were recommended for statin based on ACC/AHA guidelines as compared with 17.4% using the ATP III guidelines (P=0.0002).

Table 2.

Statin Recommendations by ACC/AHA and ATP III Guidelines

Figure 1.

Comparison of statin recommendation by ATP III and American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines based on the presence or absence of carotid plaque.

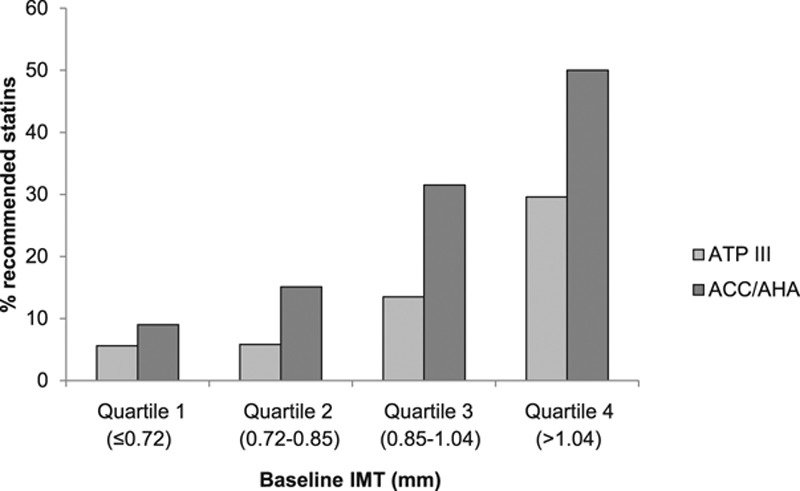

At each quartile level of baseline IMT, the rate of statin recommendation was greater using the ACC/AHA guidelines as compared with the ATP III guidelines (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of statin recommendation by ATP III and American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines based on the level of carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT). IMT indicates intima-media thickness.

Association of Carotid Atherosclerosis and Clinical Characteristics

In unadjusted linear regression, the ATP III Framingham and ACC/AHA ASCVD risk scores were each strongly associated with baseline CIMT (0.01 mm per 10% increase in risk; P<0.001) and with CIMT progression (0.01 mm per year per 10% increase in risk; P<0.001).

In a multivariable adjusted model controlling for race, sex, and ACC/AHA ASCVD risk score, baseline carotid plaque was independently associated with age (per decade; PR, 1.41; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.14–1.74; P=0.002), opportunistic infection (PR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.18–1.99; P=0.001), pack per year of smoking (per 10 years; PR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.00–1.10; P=0.05), and LDL cholesterol (per doubling; PR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.13–2.00; P=0.005). Baseline mean CIMT was independently and positively associated with age (per decade; PR, 0.137; 95% CI, 0.071–0.203; P<0.001), hypertension (PR, 0.081; 95% CI, 0.005–0.156; P=0.037), LDL cholesterol (per doubling; PR, 0.107; 95% CI, 0.04–0.174; P=0.002), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (per doubling; PR, 0.02; 95% CI, 0.001–0.039; P=0.038). Progression of CIMT was independently and positively associated with age (per decade; PR, 0.105; 95% CI, 0.04–0.169; P=0.002), hypertension (PR, 0.077; 95% CI, 0.002–0.153; P=0.045), and LDL cholesterol (per doubling; PR, 0.112; 95% CI, 0.046–0.179; P=0.001).

In a multivariable Cox proportional hazard model adjusted by demographics, including ATP III FRS and ACC/AHA ASCVD risk score, and significant covariates, including body mass index, hepatitis C infection, nadir CD4 count, and CRP, baseline IMT (hazard ratio, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.05–1.33; P=0.005) and plaque (hazard ratio, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.02–4.08; P=0.037) were independent predictors of death (Table 3), whereas ATP III FRS and ACC/AHA ASCVD risk score were not.

Table 3.

Association of Risk Scores and IMT With All-Cause Mortality

Discussion

The ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines recommend statin therapy for primary prevention in adults based on ASCVD risk scores that are calculated using traditional CVD risk factors.2 Although HIV-infected adults have an increased risk for atherosclerotic events, cardiac risk assessments created for the general population often underestimate CVD risk in the HIV-infected population and, therefore, fail to recommend preventive therapy, such as statins to HIV-infected adults. In our study of HIV-infected adults, we demonstrated the following: (1) using the ACC/AHA guidelines, more subjects would be recommended for statin therapy as compared with ATP III guidelines; (2) both ACC/AHA and ATP III guidelines were strongly associated with CIMT and IMT progression in HIV; (3) among HIV-infected individuals with carotid plaque at baseline, >2 of 3 were not identified for statin therapy using either guideline; (4) baseline IMT and baseline presence of plaque were independently predictive of death in this cohort, whereas ACC/AHA and ATP III guidelines were not. Our findings have significant clinical implications for HIV-infected individuals who, using traditional risk calculators, may not be identified to be at an elevated risk for ASCVD but who may be considered for statin therapy.

We found that HIV-infected adults who were recommended for statin therapy by the ACC/AHA guidelines, were older, had a greater prevalence of traditional CVD risk factors, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and smoking, higher blood pressures, and had more abnormal cholesterol profiles as compared with HIV-infected adults not recommended for statin therapy. Additionally, those recommended for statins had a greater prevalence of lipodystrophy and increased use of protease inhibitors, which suggest their contribution to traditional risk factors, such as dyslipidemia. As expected, Framingham and ACC/AHA ASCVD risk scores were higher in HIV-infected adults recommended for statin therapy as compared with those who were not. In unadjusted linear regression analysis, the Framingham and ASCVD risk scores were both strongly associated with CIMT and CIMT progression. In HIV-infected adults recommended for statin therapy by the ACC/AHA guidelines, 80% of subjects had carotid plaque. These results are consistent with previously published research documenting the association between traditional CVD risk factors and carotid atherosclerosis.11 Certain traditional risk factors, such as cigarette smoking, are more prevalent in the HIV-infected population and likely contribute to some of the observed increase in CVD risk and prevalence of carotid disease in the HIV-infected population.12 Similar to the general population, application of the ACC/AHA guidelines to HIV-infected adults who have elevated CVD risk based on the presence of traditional CVD risk factors may adequately identify those who may benefit from statin therapy.

Prior studies have shown that even after controlling for traditional risk factors, HIV-infected adults have increased CVD risk.13,14 Observational studies have reported ≈2-fold increase in CVD risk in HIV-infected adults as compared with matched uninfected controls15, and this risk remains even in the setting of treated suppressed HIV disease and younger age. HIV infection itself confers a risk similar to that of traditional risk factors.16 CVD risk-assessment tools, which are based primarily on traditional risk factors and intended for use in the general population, often fail to accurately identify elevated CVD risk observed in HIV-infected subjects.17 The Framingham risk calculator and the ACC/AHA risk score underestimate actual rates of CVD in HIV by as much as 50% among individuals with an intermediate 5-year risk.18,19 In our study, despite the increase in the number of HIV-infected adults being recommended for statins, the ACC/AHA guidelines only recommended statin therapy to a minority of our subjects overall (26%) and failed to recommend statin in the majority of subjects with subclinical carotid atherosclerosis (68%). Additionally, although baseline IMT and plaque were shown to independently correlate with mortality, CVD risk scores by ATP III and ACC/AHA both failed to predict death in our HIV-infected cohort. In the general population, IMT is a strong predictor of CVD outcomes with a 1.18 relative risk for MI per 0.10 mm CIMT difference and a 1.32 relative risk for stroke per 1 standard deviation CIMT difference.20 Our group has previously reported that inflammatory biomarkers interleukin-6 and CIMT are independently predictive of all-cause mortality among treated and suppressed HIV-infected individuals.21 Although the ACC/AHA guidelines rely on their ASCVD risk score to guide treatment recommendations, the risk calculator was not derived from and never validated in an HIV-infected cohort and, therefore, may underestimate CVD risk in HIV-infected adults.2 Also, although the guidelines did not endorse the use of carotid imaging to guide treatment recommendations, they did recognize that there are special populations who may require additional risk assessments beyond the ACC/AHA risk calculator. The results of our study are consistent with prior research demonstrating the failure of the ACC/AHA guidelines to recommend statin therapy in HIV-infected adults who may have elevated CVD risk based on the presence of subclinical atherosclerosis.22 A smaller cohort of 108 HIV-infected adults without known ASCVD22 showed that 74% of HIV-infected adults with evidence of subclinical high-risk morphology coronary plaque would not have had statin therapy using the ACC/AHA guidelines. These findings may extend to other populations who have elevated atherosclerotic risk that is not completely captured by traditional risk-assessment tools.

Beyond just increasing CVD risk, HIV infection is independently associated with the development of atherosclerosis.9,14 Prior published data from our group have demonstrated that HIV-infected adults have greater CIMT at baseline and 1-year follow-up as compared with control subjects.9 Additionally, in the Study of Fat Redistribution and Metabolic Change (FRAM), HIV-infected adults had a mean CIMT that was 0.033 mm thicker than uninfected controls after adjustment for traditional CVD risk factors and baseline characteristics (P=0.005).14 Although traditional risk factors play a role in the development of atherosclerosis in HIV-infected adults, multiple lines of evidence have shown that HIV-specific factors, such as chronic inflammation and immune activation, also can contribute to the development of arterial disease.10,23,24 In a prior study, our group showed that high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels were elevated at baseline in HIV-infected adults and were significant predictors of progression of carotid atherosclerosis in the bifurcation region.10 In our current study, we found that opportunistic infections were independently associated with baseline carotid plaque, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels were independently associated with baseline mean CIMT. The lower than expected prevalence of diabetes mellitus and hypertension in our cohort also supports the possible contribution of HIV-related factors to the development of carotid atherosclerosis. Accordingly, studies in HIV-infected populations suggest that noncalcified plaque may play a key role in HIV25 and that even in the absence of detectable coronary calcium, >1 of 3 HIV-infected individuals have markedly increased IMT, suggesting that imaging modalities, such as IMT, may be a more sensitive indicator of atherosclerosis in HIV.26

Although there are many studies documenting the benefit of statin therapy in reducing cardiovascular events in adults at elevated CVD risk, there are currently no data from randomized controlled trials documenting the benefit of statin therapy specifically in a HIV-infected population with elevated risk of CVD; although a study is currently being conducted (NCT02344290). In a meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials of statin therapy that enrolled 70 388 non-HIV infected adults without established CVD, Brugts et al27 demonstrated that treatment with statins significantly reduced the risk of all-cause mortality (odds ratio [OR], 0.88; 95% CI, 0.81–0.96), major coronary events (odds ratio, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.61–0.81), and major cerebrovascular events (odds ratio, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.71–0.93). Additionally, prior data suggest that there may be benefit in using statins in subjects with low FRSs but who have evidence of subclinical carotid atherosclerosis.28 In the METEOR trial (Effect of Rosuvastatin on Progression of Cartid Intima-Media Thickness in Low-Risk Individuals With Subclinical Atherosclerosis: The Meteor Trial), 984 subjects with low 10-year FRS (<10%) and elevated CIMT (1.2–3.5 mm) were randomized to rosuvastatin 40 mg daily or placebo. After 2 years of treatment, statin treatment was significantly associated with less CIMT progression as compared with the placebo group (odds ratio, −0.0014; 95% CI, −0.0041 to 0.0014 mm per year versus odds ratio, 0.0131; 95% CI, 0.0087–0.0174 mm per year; P<0.001). Similar to the subjects in METEOR, our HIV-infected cohort had a low mean 10-year FRS of 4% but the majority (65.3%) having evidence of carotid plaque.

This was an observational study, and although we made every effort to adjust our analysis appropriately, unmeasured confounders may be present that were not accounted for. The number of deaths overall was small and the majority of deaths were not ASCVD-related in our cohort; however, despite this small number of deaths, we were able to demonstrate a significant predictive value for CIMT and not the ASCVD or ATP III risk calculators. Although carotid atherosclerosis may not be directly related to non-CVD deaths, we hypothesize that chronic inflammation and advanced immunodeficiency because of HIV infection may contribute to other non-AIDS conditions, including renal disease and malignancies. The observational design of our study along with small number of deaths does not allow us to draw definitive conclusions on the relationship between carotid atherosclerosis and non-CVD deaths.

In summary, we found that although the application of the ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines increased the number of HIV-infected adults recommended for statin therapy as compared with the ATP III guidelines, the majority of HIV-infected adults with evidence of subclinical atherosclerosis were not recommended for statins. The independent associations found between (1) HIV-related factors and carotid atherosclerosis and (2) carotid atherosclerosis, but not ASCVD risk scores, and mortality suggest that elevated CVD risk in the HIV-infected population may not be accurately captured using traditional risk-assessment tools. Future studies are needed to determine whether the assessment for subclinical atherosclerosis may help improve risk stratification in the HIV population and identify HIV-infected adults who may be considered for statin therapy.

Acknowledgments

Dr Phan accessed and analyzed the data. Dr Hsue had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs Phan and Hsue were responsible for the study design, data analysis interpretation, drafting and revision of the article, as well as supervision and obtaining funding for the study. Y. Ma and Dr Scherzer assisted with data analysis, critical revision of the article, and statistical analysis and supervision of the study. B. Weigel, D. Li, and S. Hur were responsible for acquisition of the data, revision of the article, statistical analysis, and technical support. S.C. Kalapus assisted in data acquisition, analysis, article revision, and supervision of the study. Finally, Dr Deeks was responsible for data acquisition, revision of the article, and obtaining funding for the study.

Sources of Funding

This study was funded in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K24AI112393 to Dr Hsue ). The SCOPE (Studies of the Consequences of the Protease Inhibitor Era) cohort is supported in part also by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K24AI069994 to Dr Deeks), the University of California, San Francisco/Gladstone Institute of Virology and Immunology (P30AI027763), the University of California, San Francisco Clinical and Translational Research Institute Center (UL1RR024131), and the Center for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Systems (R24 AI067039). The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the article; and the decision to submit the article for publication.

Disclosures

Dr Hsue reports funding from Pfizer and honoraria from Gilead, outside the submitted work. Dr Deeks reports grants from Merck, outside the submitted work. The other authors report no conflicts.

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE

Although HIV is associated with increased cardiovascular risk, it is unknown whether cholesterol guidelines can appropriately identify HIV-infected adults for statin treatment. We compared the 2013 American College of Cardiology/AHA and 2004 ATP III recommendations in HIV-infected adults and evaluated associations with carotid artery intima-media thickness and plaque. Although the American College of Cardiology/AHA guidelines recommended statins to a greater number of HIV-infected adults compared with the ATP III guidelines, both guidelines failed to recommend therapy in the majority of HIV-affected adults with carotid plaque. Baseline carotid atherosclerosis but not atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk scores was an independent predictor of mortality. HIV-related factors, such as the presence of opportunistic infections and elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels, were independently associated with carotid atherosclerosis. Using traditional risk calculators may fail to identify HIV-infected adults who are at elevated cardiovascular disease risk. HIV-specific guidelines that include detection of subclinical atherosclerosis may help to identify HIV-infected adults who are at increased cardiovascular disease risk and may be considered for statins therapy.

References

- 1.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C, Kirby A, Sourjina T, Peto R, Collins R, Simes R Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, Goldberg AC, Gordon D, Levy D, Lloyd-Jones DM, McBride P, Schwartz JS, Shero ST, Smith SC, Jr, Watson K, Wilson PW, Eddleman KM, Jarrett NM, LaBresh K, Nevo L, Wnek J, Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Bozkurt B, Brindis RG, Curtis LH, DeMets D, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Ohman EM, Pressler SJ, Sellke FW, Shen WK, Smith SC, Jr, Tomaselli GF American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S1–45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feinstein MJ, Bahiru E, Achenbach C, Longenecker CT, Hsue P, So-Armah K, Freiberg MS, Lloyd-Jones DM. Patterns of cardiovascular mortality for HIV-infected adults in the United States: 1999 to 2013. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.10.030. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsue PY, Deeks SG, Hunt PW. Immunologic basis of cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected adults. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(suppl 3):S375–S382. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis200. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein JH, Korcarz CE, Hurst RT, Lonn E, Kendall CB, Mohler ER, Najjar SS, Rembold CM, Post WS American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force. Use of carotid ultrasound to identify subclinical vascular disease and evaluate cardiovascular disease risk: a consensus statement from the American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force. Endorsed by the Society for Vascular Medicine. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21:93–111. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2007.11.011. quiz 189. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, Brewer HB, Jr, Clark LT, Hunninghake DB, Pasternak RC, Smith SC, Jr, Stone NJ National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227–239. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heiss G, Sharrett AR, Barnes R, Chambless LE, Szklo M, Alzola C. Carotid atherosclerosis measured by B-mode ultrasound in populations: associations with cardiovascular risk factors in the ARIC study. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:250–256. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsue PY, Lo JC, Franklin A, Bolger AF, Martin JN, Deeks SG, Waters DD. Progression of atherosclerosis as assessed by carotid intima-media thickness in patients with HIV infection. Circulation. 2004;109:1603–1608. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124480.32233.8A. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124480.32233.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsue PY, Scherzer R, Hunt PW, Schnell A, Bolger AF, Kalapus SC, Maka K, Martin JN, Ganz P, Deeks SG. Carotid intima-media thickness progression in HIV-infected adults occurs preferentially at the carotid bifurcation and is predicted by inflammation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1:jah3–e000422. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.111.000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oren A, Vos LE, Uiterwaal CS, Grobbee DE, Bots ML. Cardiovascular risk factors and increased carotid intima-media thickness in healthy young adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Young Adults (ARYA) Study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1787–1792. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.15.1787. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.15.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tesoriero JM, Gieryic SM, Carrascal A, Lavigne HE. Smoking among HIV positive New Yorkers: prevalence, frequency, and opportunities for cessation. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:824–835. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9449-2. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9449-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsue PY, Waters DD. What a cardiologist needs to know about patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Circulation. 2005;112:3947–3957. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.546465. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.546465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grunfeld C, Delaney JA, Wanke C, Currier JS, Scherzer R, Biggs ML, Tien PC, Shlipak MG, Sidney S, Polak JF, O’Leary D, Bacchetti P, Kronmal RA. Preclinical atherosclerosis due to HIV infection: carotid intima-medial thickness measurements from the FRAM study. AIDS. 2009;23:1841–1849. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d3b85. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d3b85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paisible AL, Chang CC, So-Armah KA, Butt AA, Leaf DA, Budoff M, Rimland D, Bedimo R, Goetz MB, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Crane HM, Gibert CL, Brown ST, Tindle HA, Warner AL, Alcorn C, Skanderson M, Justice AC, Freiberg MS. HIV infection, cardiovascular disease risk factor profile, and risk for acute myocardial infarction. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68:209–216. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000419. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, Skanderson M, Lowy E, Kraemer KL, Butt AA, Bidwell, Goetz M, Leaf D, Oursler KA, Rimland D, Rodriguez, Barradas M, Brown S, Gibert C, McGinnis K, Crothers K, Sico J, Crane H, Warner A, Gottlieb S, Gottdiener J, Tracy RP, Budoff M, Watson C, Armah KA, Doebler D, Bryant K, Justice AC. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:614–622. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3728. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Agostino RB., Sr Cardiovascular risk estimation in 2012: lessons learned and applicability to the HIV population. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(suppl 3):S362–S367. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis196. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Regan S, Meigs J, Massaro JM, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Grinspoon SK, Triant VA. Evaluation of the ACC/AHA CVD risk prediction algorithm among HIV-infected patients. Abstract. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. 2015;751 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson-Paul AM, Lichtenstein KA, Armon C, Buchacz K, Debes R, Chmiel J, Palella FJ, Wei SC, Skarbinski J, Brooks JT. Cardiovascular disease risk prediction in the HIV outpatient study (HOPS). Abstract. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. 2015;747 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorenz MW, Markus HS, Bots ML, Rosvall M, Sitzer M. Prediction of clinical cardiovascular events with carotid intima-media thickness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2007;115:459–467. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628875. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsu DC, Ma YF, Hur S, Li D, Rupert A, Scherzer R, Kalapus SC, Deeks S, Sereti I, Hsue PY. Plasma IL-6 levels are independently associated with atherosclerosis and mortality in HIV-infected individuals on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2016;30:2065–2074. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001149. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zanni MV, Fitch KV, Feldpausch M, Han A, Lee H, Lu MT, Abbara S, Ribaudo H, Douglas PS, Hoffmann U, Lo J, Grinspoon SK. 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and 2004 Adult Treatment Panel III cholesterol guidelines applied to HIV-infected patients with/without subclinical high-risk coronary plaque. AIDS. 2014;28:2061–2070. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000360. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsue PY, Hunt PW, Schnell A, Kalapus SC, Hoh R, Ganz P, Martin JN, Deeks SG. Role of viral replication, antiretroviral therapy, and immunodeficiency in HIV-associated atherosclerosis. AIDS. 2009;23:1059–1067. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832b514b. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832b514b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsue PY, Hunt PW, Sinclair E, Bredt B, Franklin A, Killian M, Hoh R, Martin JN, McCune JM, Waters DD, Deeks SG. Increased carotid intima-media thickness in HIV patients is associated with increased cytomegalovirus-specific T-cell responses. AIDS. 2006;20:2275–2283. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280108704. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280108704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Post WS, George RT, Budoff M. HIV infection and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:923–924. doi: 10.7326/L14-5033-2. doi: 10.7326/L14-5033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsue PY, Ordovas K, Lee T, Reddy G, Gotway M, Schnell A, Ho JE, Selby V, Madden E, Martin JN, Deeks SG, Ganz P, Waters DD. Carotid intima-media thickness among human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients without coronary calcium. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:742–747. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.10.036. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brugts JJ, Yetgin T, Hoeks SE, Gotto AM, Shepherd J, Westendorp RG, de Craen AJ, Knopp RH, Nakamura H, Ridker P, van Domburg R, Deckers JW. The benefits of statins in people without established cardiovascular disease but with cardiovascular risk factors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2009;338:b2376. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crouse J, Raichlen J, Riley W, Evans GW, Palmer MK, O’Leary DH, Grobbee DE, Bots ML METEOR Study Group. Effect of rosuvastatin on progression of carotid intima-media thickness in low-risk individuals with subclinical atherosclerosis: the meteor trial. JAMA. 2007;297:1344–1353. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.12.1344. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.12.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]