Abstract

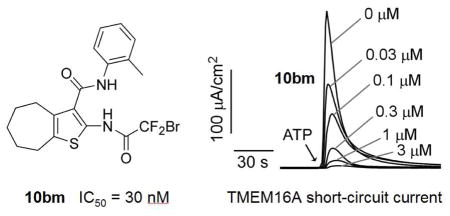

Transmembrane protein 16A (TMEM16A), also called anoctamin 1 (ANO1), is a calcium-activated chloride channel expressed widely mammalian cells, including epithelia, vascular smooth muscle tissue, electrically excitable cells and some tumors. TMEM16A inhibitors have been proposed for treatment of disorders of epithelial fluid and mucus secretion, hypertension, asthma, and possibly cancer. Herein we report by screening the discovery of 2-acylamino-cycloalkylthiophene-3-carboxylic acid arylamides (AACTs) as inhibitors of TMEM16A, and analysis of 48 synthesized analogs (10ab–10bw) of the original AACT compound (10aa). Structure-activity studies indicated the importance of benzene substituted as 2- or 4-methyl, or 4-fluoro, and defined the significance of thiophene substituents and size of the cycloalkylthiophene core. The most potent compound (10bm), which contains an unusual bromodifluoroacetamide at the thiophene 2-position, had IC50 ~ 30 nM, ~3.6-fold more potent than the most potent previously reported TMEM16A inhibitor 4 (Ani9), and >10-fold metabolic stability. Direct and reversible inhibition of TMEM16A by 10bm was demonstrated by patch-clamp analysis. AACTs may be useful as pharmacological tools to study TMEM16A function and as potential drug development candidates.

Keywords: TMEM16A, calcium-activated chloride channel, ANO1, hypertension, cancer, anoctamin, cycloalkylthiophene, 2-acylamino-cycloalkylthiophene-3-carboxylic acid arylamide

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Transmembrane protein 16A (also known as TMEM16A, ANO1, DOG1, ORAOV2, TAOS-2) is a calcium-activated chloride channel (CaCC) that is expressed in a variety of mammalian tissues including smooth muscle cells, airway mucin-secreting cells, secretory epithelia, interstitial cells of Cajal, and nociceptive neurons.1–3 TMEM16A is overexpressed in some human cancers,4, 5 and knockdown of TMEM16A inhibits cancer cell proliferation, cell cycle progression, and apoptosis.6 TMEM16A was reported recently as a biomarker for gastrointestinal stromal and esophageal tumors,7, 8 and TMEM16A expression is associated with good prognosis in PR-positive or HER2-negative breast cancer following tamoxifen treatment.9

Early studies suggested TMEM16A contains eight putative transmembrane domains with intracellular N- and C- termini, and two calmodulin binding domains.10–12 Multiple TMEM16A splice variants may explain its variable behavior in different tissues and cell types.13–16 Recent studies have questioned the role of calmodulin in TMEM16A activation, and have identified four acidic side-chain residues involved in Ca2+ binding in mouse TMEM16A: E698, E701, E730 and D734.17, 18 Other divalent cations (Sr2+ and Ni2+) appear to activate the channel as well.19 Four basic side-chain residues appear to be critical for anion selectivity in mouse TMEM16A: R511, K599, R617 and R784.20 The kinetics of TMEM16A and TMEM16B Cl− conductance are complex, with distinct fast and slow gating mechanisms, regulated by membrane voltage and Cl− concentration.21 Biophysical experiments suggest TMEM16A is present in membranes as a homodimer,22, 23 with the dimerization domain located in the N-terminal sequence.24 Recently, the C-terminal region of TMEM16A was modified to produce a constitutively active channel, providing a strategy to design TMEM16A activators.25

A 3.4Å X-ray crystal structure was solved recently of a Ca2+-activated lipid scramblase expressed in the fungus Nectria haematococca (nhTMEM16), which is ~ 40% homologous to mammalian TMEM16A, indicating a ten-transmembrane helical structure.26 Using the nhTMEM16 structure, two homology models of TMEM16A suggest it contains ten transmembrane helical segments,21, 25 revising earlier eight helix structural models.

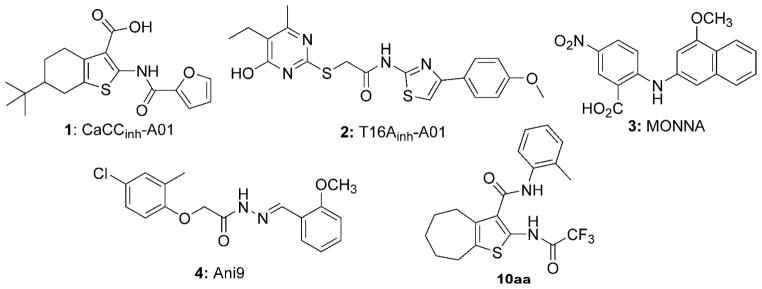

Inhibitors of TMEM16A has been proposed to be of potential utility for treatment of hypertension, asthma, inflammatory and reactive airways diseases, pain, and possibly cancer.1, 3, 4, 27 Reported inhibitors (Figure 1) include the non-selective CaCC inhibitor CaCCinh-A01 (1),28 and TMEM16A-selective inhibitors such as the thiopyrimidine aryl aminothiazole T16Ainh-A01 (2),29, 30 N-((4-methoxy)-2-naphthyl)-5-nitroanthranilic acid (MONNA) (3),31 and the acyl hydrazone Ani9 (4).32 The use of compound 2 to inhibit TMEM16A in various tissues has been reviewed.1 Compound 2 blocks Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in vascular smooth muscle cells, and relaxes mouse and human blood vessels,33 This compound also prevents serotonin-induced contractile responses in pulmonary arteries of chronic hypoxic rats, a model of pulmonary hypertension,34 and reverses EGF-induced increases in CaCC currents in T84 colonic epithelial cells.35 Recently, 2 was also shown to attenuate angiotensin II-induced cerebral vasoconstriction in rat basilar arteries, further supporting TMEM16A as a target in vascular function, hypertension, and stroke.36 The non-selective CaCC inhibitor 1 was shown to accelerate the degradation of TMEM16A in cancer cells by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway by a mechanism that may not involve channel inhibition.37 Several recent studies address inhibitor selectivity. Studies of 1, 2, and 3 in isolated resistance arteries suggested poor TMEM16A selectivity for all three compounds.38 Another study reported 1 as a non-selective inhibitor of CaCCs TMEM16A and Bestrophin1, while 2 selectively inhibited TMEM16A but with low potency.39 As such, the discovery of potent and selective TMEM16A inhibitors continues to be a focus of multiple laboratories.

Figure 1.

Structures of the non-selective CaCC inhibitor 1,28 and TMEM16A inhibitors 2,29, 30 3,31 4,32 and the new class of cycloalkylthiophene inhibitors (10aa) described herein.

Herein, we report the discovery by screening of a 2-acylamino-cycloalkylthiophene-3-carboxylic acid arylamide (AACT) class of TMEM16A inhibitors, exemplified by 10aa. Synthesis and evaluation of 48 analogs of 10aa has provided compounds with substantially improved TMEM16A inhibition potency and metabolic stability than the recently reported compound 4.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

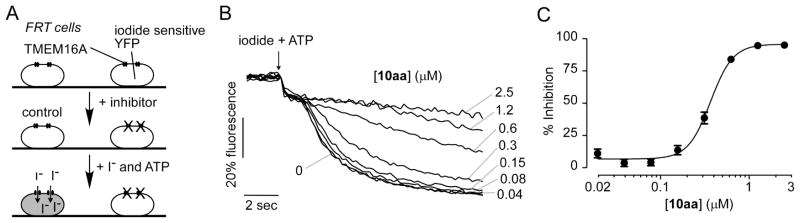

A medium-throughput screening assay was previously developed to identify small molecule inhibitors of TMEM16A.40 The screen utilized FRT cells that were stably transfected with human TMEM16A and the iodide-sensitive fluorescent protein YFP-H148Q/I152L/F46L. The assay involved addition of test compounds to the cells for 10 min in a physiological chloride-containing solution, followed by addition of an iodide solution containing ATP. ATP is a P2Y2 agonist in FRT cells used to increase cytosolic Ca2+ and activate TMEM16A channels. TMEM16A-facilitated iodide influx was determined from the initial time course of decreasing YFP fluorescence. TMEM16A inhibitors reduce iodide influx, resulting in a reduced rate of decreasing fluorescence. Here, screening of 50,000 drug-like synthetic small molecules not previously tested identified 2-acylaminocycloalkylthiophene-3-carboxylic acid arylamide (AACT) 10aa with IC50 ~ 0.42 μM (Figure 2). The structure of 10aa resembles that of the previously identified non-selective CaCC inhibitor 1,28 although the latter molecule is substituted with a tert-butyl group, has a different assortment of functionality on the thiophene (e.g. lacking the haloacetamide), and was reported to be significantly less potent (IC50 = 2.1 μM) than 10aa against TMEM16A.29

Figure 2.

Identification of TMEM16A inhibitors. A. Schematic of assay. FRT cells stably expressing TMEM16A and a halide-sensitive YFP sensor were incubated for 10 min with test compound. Extracellular addition of addition of iodide and ATP results in YFP quenching whose rate is reduced by TMEM16A inhibition. B. Original fluorescence quenching curves for inhibition of TMEM16A by 10aa. C. Concentration-dependent inhibition of TMEM16A by 10aa (mean ± S.E., n=4).

Motivated by the submicromolar potency of 10aa and the modularity and synthetic accessibility of this scaffold, we further optimized this class of compounds. The only other reported biological activity of AACT compounds is inhibition of the protozoan parasite Leishmania donovani (EC50 = 6.4 μM), with no cytotoxicity seen against human macrophages (CC50 > 50 μM).41 The most potent inhibitor in the anti-parasite study was an analog of 10aa, with 2-methylanilide replaced with 4-methoxyanilide.

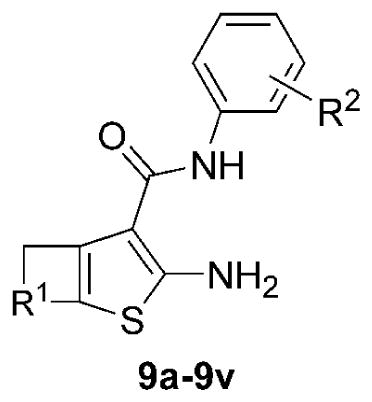

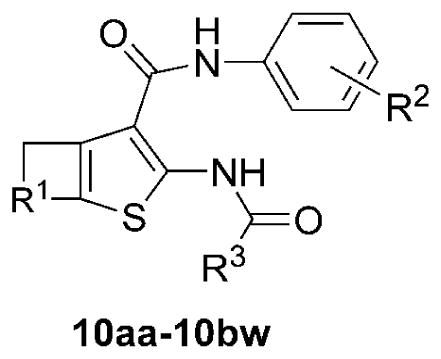

Chemistry

AACT compounds were prepared using the modular synthetic strategy shown in Scheme 1. The synthesis begins with the generation of substituted aryl cyanoacetamides, followed by a two-step Knoevenagel-Gewald sequence to generate 2-aminothiophenes, and coupling with simple electrophilic acylating agents. Substituted anilines (5a–5k) were coupled with cyanoacetic acid using EDCI-HCl to generate the library of cyanoacetamides (6a–6k). The substituent composition of this library, prepared typically in good yields, is reported in Table 1, with some of the cyanoacetamides also being commercially available.

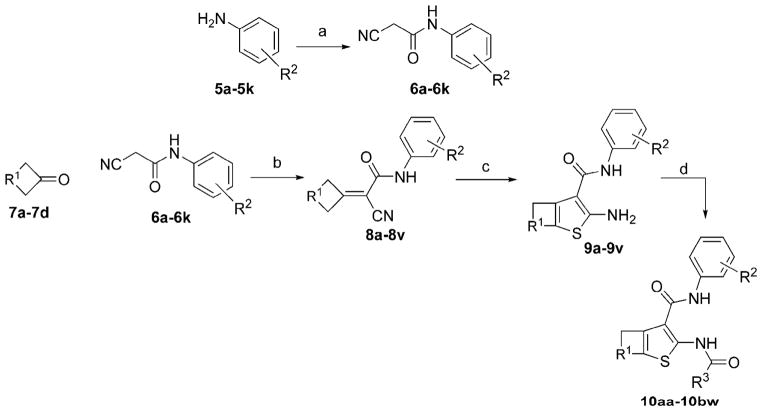

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 2-acylamino-cycloalkylthiophene-3-carboxylic acid arylamides. Reagents and conditions: (a) cyanoacetic acid (1.0 eq) and EDCI-HCl (1.2 eq) (rt, 6 min); (b) cycloalkyl ketone, NH4OAc, and AcOH (100 °C, 60 min); (c) S8, morpholine (3.0 eq), EtOH (90 0C, 5h); (d) electrophilic acylating agent (1.3 eq), Et3N (1.3 eq) (rt, 10 min) or difluoroiodoacetic acid (1.2 eq) and EDCI-HCl (1.5 eq) (rt, 60 min).

Table 1.

Synthesis yields for EDCI-mediated cyanoacetamide generation reactions (5 → 6); yields (%) are of the isolated or purified products. Purity of compounds was >95% based on HPLC-LCMS analysis at 254 nm, and absence of impurities was confirmed by 1H NMR spectra.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Product Cyanoacetamide | SM Aniline | R2 | Isolated Yield (%) |

| 6a | 5a | 2-(CH3) | 50 |

| 6b | 5b | H | purchased |

| 6c | 5c | 2-(CH2CH3) | 76 |

| 6d | 5d | 2-F | 78 |

| 6e | 5e | 4-F | 70 |

| 6f | 5f | 2-Cl | 82 |

| 6g | 5g | 3-Cl | 80 |

| 6h | 5h | 4-Cl | 89 |

| 6i | 5i | 4-(CF3) | 79 |

| 6j | 5j | 4-(CH3) | 86 |

| 6k | 5k | 2-(OCF3) | 87 |

Next, the substituted aryl cyanoacetamides (6a–6k) were condensed with a small collection of cycloalkyl ketones (7a–7d) under buffered acid-catalyzed aldol conditions (AcOH:NH4OAc) to generate Knoevenagel adducts (8a–8v). While excess cyclic ketone was useful to obtain high conversion, we were pleased that this material could be removed by evaporation. The Knoevenagel adducts were subjected to the Gewald cyclization reaction in the presence of molecular octasulfur (S8), to yield 2-amino-cycloalkylthiophene-3-carboxylic acid arylamides (9a–9v), which were typically crystalline and easily purified by trituration. The composition of the library and yields for the Knoevenagel and Gewald reactions are reported in Table 2, separated by the different cycloalkyl ketones.

Table 2.

Synthesis yields for Knoevenagel reaction/aminothiophene formation (7 + 6 → [8] → 9). Yields (%) are of the isolated or purified products. Purity of compounds was >95% based on HPLC-LCMS analysis at 254 nm, and absence of impurities was confirmed by 1H NMR spectra.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product Aminothiophene | SM Cyanoacetamide | Isolated Yield (%) Intmdt 8a–8v | Isolated Yield (%) Product 9a–9v | R1 | R2 |

| (based on cycloheptanone 7a) | |||||

| 9a | 6a | 87 | 50 | -(CH2)4- | 2-(CH3) |

| 9b | 6b | 52 | 90 | -(CH2)4- | H |

| 9c | 6c | 48 | 70 | -(CH2)4- | 2-(CH2CH3) |

| 9d | 6d | 93 | 51 | -(CH2)4- | 2-F |

| 9e | 6e | 60 | 69 | -(CH2)4- | 4-F |

| 9f | 6f | 70 | 85 | -(CH2)4- | 2-Cl |

| 9g | 6g | 73 | 93 | -(CH2)4- | 3-Cl |

| 9h | 6h | 90 | 67 | -(CH2)4- | 4-Cl |

| 9i | 6i | 76 | 98 | -(CH2)4- | 4-(CF3) |

| 9j | 6j | 58 | 7 | -(CH2)4- | 2-(OCF3) |

| (based on cyclohexanone 7b) | |||||

| 9k | 6b | 70 | 62 | -(CH2)3- | H |

| 9l | 6a | 90 | 95 | -(CH2)3- | 2-(CH3) |

| 9m | 6j | 55 | 37 | -(CH2)3- | 4-(CH3) |

| 9n | 6e | 32 | 97 | -(CH2)3- | 4-F |

| (based on tetrahydro-4H-pyran-4-one 7c) | |||||

| 9o | 6a | 86 | 92 | -CH2OCH2- | 2-(CH3) |

| 9p | 6f | 66 | 21 | -CH2OCH2- | 2-Cl |

| 9q | 6j | 55 | 23 | -CH2OCH2- | 4-(CH3) |

| 9r | 6e | 70 | 26 | -CH2OCH2- | 4-F |

| (based on cyclopentanone 7d) | |||||

| 9s | 6a | 60 | 92 | -(CH2)2- | 2-(CH3) |

| 9t | 6j | 60 | 55 | -(CH2)2- | 4-(CH3) |

| 9u | 6f | 84 | 72 | -(CH2)2- | 2-Cl |

| 9v | 6k | 38 | 82 | -(CH2)2- | 2-(OCF3) |

Finally, coupling of the aminothiophenes (9a–9v) with alkyl and fluoroalkyl acyl chlorides, anhydrides, or EDCI-coupling was done to generate the final desired AACT compounds (10aa–10bw), also typically as crystalline solids, in fair to good yields (Table 3). After completion of a 1st generation of compounds (10aa–10bj) based on simple alkyl and fluoroalkyl groups at the R3 position, we designed a 2nd generation library with halodifluoroalkyl (chloro, bromo, and iodo) and heptafluorobutyryl at R3, based on the most promising combinations of R1 and R2 (10bk–10bw). The synthesis of the difluoroiodoacetyl inhibitors (10bn, 10bq, 10bt, and 10bw) was accomplished by EDCI-mediated coupling of aminothiophenes with difluoroiodoacetic acid. In total, 49 inhibitor candidates were prepared by variations at the R1, R2, and R3 positions. The structure and purity of the final products were confirmed by 1H-NMR, ESI-LCMS (UV absorption detection at 254 nm), with purities estimated to be >95%.

Table 3.

Coupling yields and TMEM16A inhibition of AACT compounds (10aa–10bw). Yields (%) are of the isolated or purified products. IC50 (μM) for inhibition of TMEM16A anion conductance using a fluorescence plate reader (FPR) assay (SEM in parentheses; n = 3). Purity of assayed compounds was >95% based on HPLC-LCMS analysis at 254 nm, and absence of impurities was confirmed by inspection of 1H NMR spectra. aLow solubility in DMSO.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product Final | SM Amino thiophene | R1 | R2 | R3 | Isolated Yield (%) | FPR IC50 TMEM16A (μM) |

| (based on cycloheptanone 7a) | ||||||

| 10aa | 9a | -(CH2)4- | 2-(CH3) | CF3 | 61 | 0.42 (0.03) |

| 10ab | 9a | -(CH2)4- | 2-(CH3) | CF2CF3 | 65 | 1.3 |

| 10ac | 9a | -(CH2)4- | 2-(CH3) | CH3 | 82 | >10 |

| 10ad | 9a | -(CH2)4- | 2-(CH3) | CH2CH3 | 70 | >20 |

| 10ae | 9b | -(CH2)4- | H | CF3 | 38 | 0.3 (0.005) |

| 10af | 9b | -(CH2)4- | H | CF2CF3 | 97 | 2.5 |

| 10ag | 9b | -(CH2)4- | H | CH3 | 80 | >20 |

| 10ah | 9b | -(CH2)4- | H | CH2CH3 | 87 | 1.2 |

| 10ai | 9c | -(CH2)4- | 2-(CH2CH3) | CF3 | 6 | 1.3 (0.7) |

| 10aj | 9d | -(CH2)4- | 2-F | CF3 | 48 | 1.3 |

| 10ak | 9e | -(CH2)4- | 4-F | CF3 | 60 | 0.32 (0.11) |

| 10al | 9f | -(CH2)4- | 2-Cl | CF3 | 87 | 0.66 (0.02) |

| 10am | 9f | -(CH2)4- | 2-Cl | CF2CF3 | 91 | >20 |

| 10an | 9g | -(CH2)4- | 3-Cl | CF3 | 23 | 5 (0.2) |

| 10ao | 9h | -(CH2)4- | 4-Cl | CF3 | 4 | 3 (0.09) |

| 10ap | 9i | -(CH2)4- | 4-(CF3) | CF3 | 2 | 5 (0.10) |

| 10aq | 9j | -(CH2)4- | 2-(OCF3) | CF3 | 12 | 1.3 (0.2) |

| 10ar | 9j | -(CH2)4- | 2-(OCF3) | CF2CF3 | 30 | 2.7 (0.07) |

| 10as | 9j | -(CH2)4- | 2-(OCF3) | CH3 | 55 | >20 |

| 10at | 9j | -(CH2)4- | 2-(OCF3) | CH2CH3 | 50 | >20 |

| (based on cyclohexanone 7b) | ||||||

| 10au | 9k | -(CH2)3- | H | CF3 | 93 | 0.37 (0.01) |

| 10av | 9l | -(CH2)3- | 2-(CH3) | CF3 | 17 | 0.17 (0.001) |

| 10aw | 9m | -(CH2)3- | 4-(CH3) | CF3 | 30 | 0.22 (0.01) |

| 10ax | 9n | -(CH2)3- | 4-F | CF3 | 48 | 0.49 (0.02) |

| (based on tetrahydro-4H-pyran-4-one 7c) | ||||||

| 10ay | 9o | -CH2OCH2- | 2-(CH3) | CF2CF3 | 6 | 1.6 (0.09) |

| 10az | 9o | -CH2OCH2- | 2-(CH3) | CH2CH3 | 40 | 3 (0.09) |

| 10ba | 9p | -CH2OCH2- | 2-Cl | CF3 | 67 | 1.3 |

| 10bb | 9q | -CH2OCH2- | 4-(CH3) | CF3 | 38 | 5 (0.1) |

| 10bc | 9r | -CH2OCH2- | 4-F | CF3 | 15 | 3.8 (0.09) |

| (based on cyclopentanone 7d) | ||||||

| 10bd | 9s | -(CH2)2- | 2-(CH3) | CF3 | 10 | >20 |

| 10be | 9s | -(CH2)2- | 2-(CH3) | CF2CF3 | 37 | 6.2 |

| 10bf | 9s | -(CH2)2- | 2-(CH3) | CH3 | 38 | >20 |

| 10bg | 9s | -(CH2)2- | 2-(CH3) | CH2CH3 | 33 | >20 |

| 10bh | 9t | -(CH2)2- | 4-(CH3) | CF3 | 77 | 2.5 (0.04) |

| 10bi | 9u | -(CH2)2- | 2-Cl | CF3 | 64 | 1.3 |

| 10bj | 9v | -(CH2)2- | 2-(OCF3) | CF3 | 56 | 0.37 (0.02) |

| (2nd-generation inhibitors with novel R3 substituents, including chloro/bromo/iodo difluoroacetyl) | ||||||

| 10bk | 9a | -(CH2)4- | 2-(CH3) | CF2Cl | 27 | 0.18 (0.008) |

| 10bl | 9a | -(CH2)4- | 2-(CH3) | CF2CF2CF3 | 61 | 0.38 (0.01) |

| 10bm | 9a | -(CH2)4- | 2-(CH3) | CF2Br | 36 | 0.083 (0.007) |

| 10bn | 9a | -(CH2)4- | 2-(CH3) | CF2I | 67 | 0.6 (0.02) |

| 10bo | 9b | -(CH2)4- | H | CF2Cl | 16 | 0.925 (0.002) |

| 10bp | 9b | -(CH2)4- | H | CF2Br | 15 | 0.23 (0.004) |

| 10bq | 9b | -(CH2)4- | H | CF2I | 13 | 0.23 (0.004) |

| 10br | 9e | -(CH2)4- | 4-F | CF2Cl | 19 | 0.84 (0.04) |

| 10bs | 9e | -(CH2)4- | 4-F | CF2Br | 32 | 0.45 (0.03) |

| 10bt | 9e | -(CH2)4- | 4-F | CF2I | 60 | 0.15 (0.002) |

| 10bu | 9v | -(CH2)2- | 2-(OCF3) | CF2Cl | 81 | >20a |

| 10bv | 9v | -(CH2)2- | 2-(OCF3) | CF2Br | 40 | 0.70a (0.002) |

| 10bw | 9v | -(CH2)2- | 2-(OCF3) | CF2I | 50 | 1.88 (0.04) |

Biological characterization

2-Acylamino-cycloalkylthiophene-3-carboxylic acid arylamides 10aa–10bw were initially evaluated for inhibition of TMEM16A anion channel function using a cell-based functional plate reader assay as reported.29, 30, 40 IC50 values determined from concentration-inhibition measurements are summarized in Table 3.

The 1st generation library (10aa–10bj) showed several compounds with apparent IC50 of 0.2–0.3 μM: 10aa (initial inhibitor), 10ae, 10ak, 10au, 10av, 10aw. These results showed that 5-, 6-, and 7-member rings were tolerated at the R1 position, while compounds based on tetrahydro-4H-pyran-4-one (10ay–10bc) were inactive. The best inhibitors contained H, 2- or 4-(CH3), or 4-F on the aromatic ring (R2), and CF3 as the acylamido substituent (R3). Inhibitors with differing groups at R2, such as 2-F, 2-Cl, 3-Cl, 4-Cl, 4-(CF3), 2-(OCF3), were less potent. Likewise, compounds with alternative substituents at R3, including CF2CF3, CH3, and CH2CH3, also had reduced potency.

Based on results that favored CF3 at the R3 position, we designed a 2nd-generation library (10bk–10bw) that incorporated novel groups such as chlorodifluoro, bromodifluoro, or difluoroiodo, probing steric and electronic effects at that position. The 2nd-generation library focused on structural features seen in the more active compounds from the 1st-generation library (R1 = -(CH2)4-; R2 = 2-(CH3), H, or 4-F). One 2nd-generation compound was synthesized that incorporated a heptafluorobutyryl substituent (10bl) to evaluate the effect of a multi-carbon fluoroalkyl group. We found three 2nd- generation compounds with lower apparent IC50 of 0.08–0.18 μM: 10bk, 10bm, and 10bt. Additionally, the full series of inhibitor candidates (10aa–10bw) was subjected to a computational screen for pan-assay interference (PAINS),42 and all 49 compounds passed.

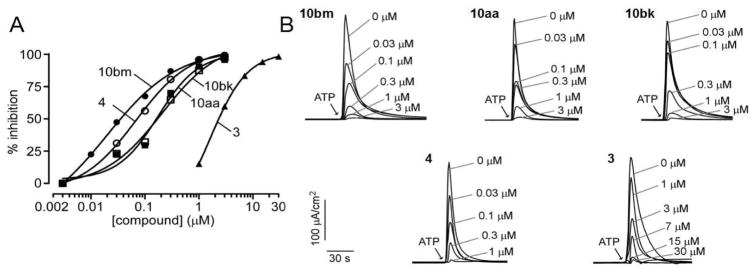

The most potent TMEM16A inhibitors identified using the semi-quantitative plate reader assay were then studied using a short-circuit current assay in which measured current is a linear measure of TMEM16A Cl− conductance. Compounds 10aa (original inhibitor from screen), 10ae, 10bk, 10bm, 10bn and 10bt were tested, and compared with reported inhibitors 2, 3 and 4. Concentration-dependence for the selected compounds is shown in Figure 3, with IC50 values summarized in Table 4. Non-transfected FRT cells shows no signal upon ATP stimulation (Figure S1). By the short-circuit current assay, 10aa showed an IC50 of 0.26 ± 0.10 μM (n=3), similar to the chlorodifluoroacetamide 10bk with IC50 of 0.23 μM. Difluoroiodoacetamides 10bn and 10bt were less potent with IC50 of 0.73 and 0.60 μM, respectively. Notably, bromodifluoroacetamide 10bm had IC50 of 0.030 ± 0.010 μM (n=3). The IC50 of 4 using this assay was 0.11 μM, close to 0.077 μM reported previously;32 compound 3 had IC50 of 1.6 μM by the short-circuit current assay, significantly less potent than the reported IC50 of 0.08 μM using a Xenopus laevis oocyte assay.31 Inhibitor 2 was a previously reported to have an IC50 of 1 μM.29

Figure 3.

Short-circuit current measurement of TMEM16A inhibition by 10aa, 10bk and 10bm, and previously reported compounds 3 and 4. Measurements were done in FRT cells expressing human TMEM16A. A. Summary of dose-response data (mean ± SEM, n = 3). B. Examples of original data in which inhibitors were added 5 min prior to TMEM16A activation by 100 μM ATP.

Table 4.

Characterization of AACT analogs. Concentration-dependent inhibition of TMEM16A measured by short-circuit current assay; TMEM16B and non-TMEM16 anion conductance measured using a fluorescence plate reader assay; cell viability measured in HT-29 cells. (SEM in parentheses; n=3).

| Inhibitor | R1 | R2 | R3 | TMEM16A IC50 (μM) | TMEM16B IC50 (μM) | HT-29 IC50 (μM) | Cellular survival % at 5 μM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | – | – | – | ~1ref 29 | ~4ref 32 | 5.0 | 97 |

| 3 | – | – | – | 1.6 | 13 | >20 | 100 |

| 4 | – | – | – | 0.11 | >20 | 0.3 | 102 |

| 10aa | -(CH2)4- | 2-(CH3) | CF3 | 0.26 (0.10) | 1.4 (0.05) | 4.0 | 99 |

| 10ae | -(CH2)4- | H | CF3 | 0.13 | 4.6 (0.4) | 5.0 | 97 |

| 10bk | -(CH2)4- | 2-(CH3) | CF2Cl | 0.23 | 0.4 (0.01) | 9.5 | 98 |

| 10bm | -(CH2)4- | 2-(CH3) | CF2Br | 0.030 (0.010) | 0.4 (0.04) | 5.4 | 97 |

| 10bn | -(CH2)4- | 2-(CH3) | CF2I | 0.73 | 1.4 (0.05) | 3.5 | 96 |

| 10bt | -(CH2)4- | 4-F | CF2I | 0.60 | 1.1 (0.13) | 5.0 | 97 |

Ion channel specificity and cytotoxicity were determined for the six most potent AACT compounds as well as previously reported compounds 2, 3 and 4 (Table 4). Selectivity was studied for TMEM16B, an isoform of TMEM16A that functions as a CaCC and regulates action potential firing in olfaction.43 Inhibition of TMEM16B by the low-potency CaCC inhibitor anthracene-9-carboxylic acid was recently reported.44 Compounds 3 and 4 (IC50 13 and >20 μM, respectively) were selective against TMEM16B, while 2 was less selective (IC50 4 μM). The AACT compounds displayed modest selectivity against TMEM16B, with an IC50 range of 0.4–1.4 μM. Two of the more potent AACT inhibitors of TMEM16A (10bk and 10bm) were also among the more potent against TMEM16B with IC50 ~ 0.4 μM. Compound 4 showed 181-fold selectivity against TMEM16B, while 10bm achieved 13-fold selectivity. We further assayed compound potency on endogenous non- TMEM16A Ca2+-activated Cl− channel in HT-29 cells.28 In general, the AACT compounds were weak inhibitors of CaCCs in HT-29 cells (IC50 3.5–9.5 μM), contrasting with 2 (IC50 5 μM), 3 (IC50 > 20 μM), and 4 (IC50 0.3 μM). None of the compounds examined showed significant toxicity using an Alamar blue assay at concentrations up to 5 μM. Additionally, none of the compounds inhibited the cAMP-activated Cl− channel cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (data not shown).

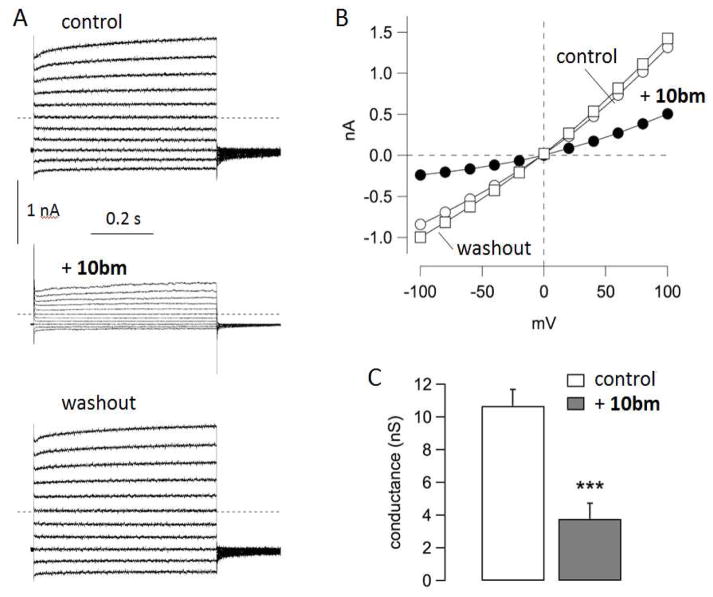

Inhibition of TMEM16A by 10bm was also investigated by the patch-clamp technique using the inside-out configuration. Membrane patches were excised from TMEM16A-expressing FRT cells. With the inside-out configuration, the cytosolic side of the membrane is exposed to the bath solution. To activate TMEM16A, the bath solution contained a free Ca2+ concentration of 305 nM. Under these conditions, relatively large membrane currents were recorded due to the presence of multiple TMEM16A channels (Figure 4). The currents had the typical characteristics of TMEM16A with outward rectification and time-dependent activation at positive membrane potentials. Addition to the bath of 10bm (250 nM) by perfusion resulted in rapid inhibition of membrane currents, which fully recovered following washout. To further examine the specificity of 10bm, short-circuit current measurement showed that 10bm inhibited ionomycin- and carbachol-activated chloride conductance (Figure S2A), indicating that 10bm did not inhibit chloride conductance through an ATP-stimulated purinergic G protein-coupled receptor mechanism. Further, cytoplasmic calcium was not altered by 1 μM 10bm as seen in Fluo-4 fluorescence measurement of ATP-stimulated cytoplasmic calcium elevation (Figure S2B). These results support reversible TMEM16A inhibition by 10bm by a direct interaction mechanism.

Figure 4.

Patch-clamp studies of TMEM16A inhibition by 10bm. A. Representative currents recorded from an inside-out membrane patch. Cytosolic (bath) free Ca2+ concentration was 305 nM. Each panel of traces show superimposed membrane currents elicited at membrane potentials in the range −100 to +100 mV. Currents were recorded under control conditions, after application by perfusion of 10bm (250 nM), and after washout. B. Current-voltage relationships from the experiment shown in A. Current values were measured at the end of each voltage step. C. Summary of conductance values at +100 mV obtained from five independent experiments (***, p < 0.001 by paired t test).

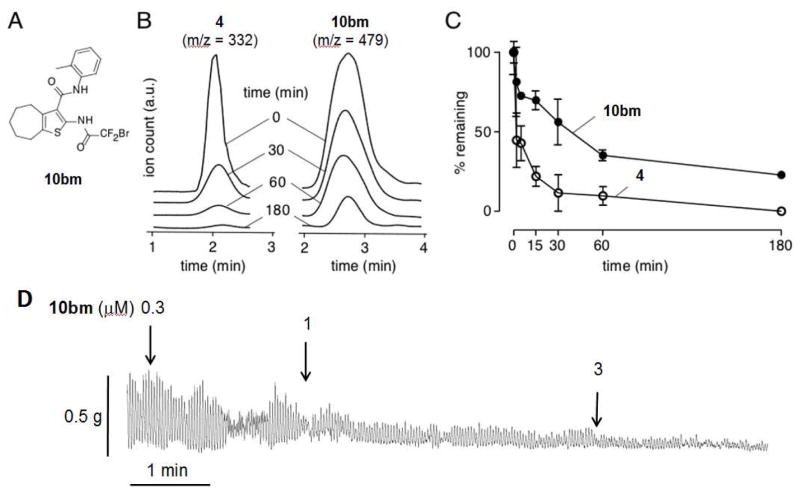

In vitro metabolic stability was determined using a hepatic microsome assay for the most potent AACT inhibitor 10bm (Figure 5A) and previously reported compound 4. These compounds were incubated with rat liver microsomes and NADPH, and non-metabolized compounds were quantified by ESI-LCMS. Figure 5B shows near complete degradation of 4 at 180 min, whereas for the same incubation time ~30% of 10bm remained. Figure 5C summarizes the time course of compound degradation showing remarkably greater stability of 10bm compared to 4. Inhibitor 10bm could be potentially metabolized by amide-bond hydrolysis or oxidation of the benzene or aryl methyl. We speculate that 4 could be oxidized at the aryl methyl or N-N bond; or hydrolyzed at the amide or hydrazone linkages.

Figure 5.

Microsomal stability of 10bm and 4 in the presence of hepatic microsomes and NADPH, AND inhibition of isometric smooth muscle contractions of ex vivo mouse ileum by 10bm. A. Structure of 10bm. B. LC/MS traces showing total ion counts as a function of incubation time. C. Summary of in vitro metabolic stability shows percent of remaining compounds over time (mean ± S.E.M., n=3). D. Isometric smooth muscle contraction in mouse ileum showing suppression by 10bm. Data representative of three separate experiments.

We have found the bromodifluoroacetamide functional group present in 10bm to have long-term shelf stability (> 6 months) as a solid or in DMSO stock solution. In aqueous solution, there was gradual degradation of 10bm, with 72% and 30% remaining at 1 and 2 days, respectively (Figure S3A). ESI-LCMS analysis suggested that degradation of 10bm involves: solvolysis, elimination, and hydrolysis of the resulting acid fluoride to a stable N-substituted oxalamic acid (Figure S3B). This solvolytic pathway has not been previously reported for the bromodifluoroacetamide functional group. While we feel this degradation is slow enough to not effect potential pharmacological use of 10bm, these results discourage multi-day storage in aqueous solution. Kinetic aqueous solubility was measured for 10bm to be 0.04 mg/mL by titration.

To demonstrate one predicted biological action of TMEM16A inhibition, we measured intestinal smooth muscle contraction. The effect of 10bm was determined when added to the bath in an ex vivo preparation of mouse ileum. As shown in Figure 5D, 10bm strongly inhibited spontaneous isometric contractions of ileum in a concentration-dependent manner.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we identified a new inhibitor of TMEM16A (10aa) by screening. The scaffold (designated AACT) is modular, allowing the synthesis and characterization of 48 analogs (10ab–10bw). The synthesis utilized substituted aryl cyanoacetamides (6a–6k) which were converted to 2-amino-cycloalkylthiophene-3-carboxylic acid arylamides (9a–9v) and acylated to afford the final library. The most potent compound in the series (10bm) had an IC50 of 0.030 μM, making it currently the most potent reported TMEM16A inhibitor. Patch-clamp analysis supported reversible inhibition of TMEM16A by 10bm by a mechanism involving direct interaction. 10bm had remarkably greater metabolic stability than the previously reported compound 4. Finally, 10bm was shown to inhibit smooth muscle contractions in mouse ileum in concentration-dependent manner, illustrating one of its potential biomedical applications. The high potency and microsomal stability of AACT 10bm supports its potential as a pharmacological tool to study TMEM16A function and as a potential candidate for further development.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Chemistry

The detailed synthesis of all newly reported synthetic precursor molecules and final inhibitor candidates is presented in Supporting Information. Purity of assayed compounds was >95% based on HPLC-LCMS analysis at 254 nm, and absence of impurities was additionally confirmed by inspection of 1H NMR spectra, and examination of at least one other wavelength (typically 320 nm).

Biology

Cell lines and culture

Fischer Rat Thyroid (FRT) cells stably co-expressing TMEM16A, TMEM16B and human wild-type CFTR and the halide-sensitive yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)- H148Q were cultured as described.29 HT-29 expressing YFP were cultured as described.28 FRT cells were cultured on plastic in Coon’s-modified Ham’s F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. For plate reader assays, cells were plated in black 96-well microplates (Corning-Costar Corp., New York, N.Y.) at a density of 20,000 cells per well and assayed 24–48 hours after plating.

TMEM16A functional assay

TMEM16A functional plate-reader assay was done as previously described.29 Briefly, each well of 96-well plate containing the TMEM16A-expressing FRT cells was washed twice with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) leaving 50 μl. Test compounds (0.5 μl in DMSO) were added to each well at specified concentration. After 10 min each well was assayed individually for TMEM16A-mediated I− influx by recording fluorescence continuously (400 ms/point) for 2 s (baseline), then 50 μl of 140 mM I− solution containing 300 μM ATP was added at 2 s, and fluorescence was further read for 12 s. The initial rate of I− influx following each of the solution additions was computed from fluorescence data by nonlinear regression. TMEM16B activity was assayed similarly as described29 using FRT cells co-expressing YFP and TMEM16B.

In silico PAINS assay

A computational screen for pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS)42 was employed to identify substructures associated with promiscuous inhibition. The full series of inhibitor candidates (10aa–10bw) was converted to SMILES strings, and submitted to an internet-based implementation of the PAINS filter (http://cbligand.org/PAINS), maintained by Prof. Xiang-Qun (Sean) Xie’s laboratory at University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy.

Short-circuit current measurement

Short-circuit current measurements were done as described.30 Briefly, Snapwell inserts (Corning Costar, Corning, NY) containing TMEM16Aexpressing FRT cells were mounted in Ussing chambers (Physiological Instruments, San Diego, CA). The hemichambers were filled with 5 ml of HCO3− buffered solution (basolateral) and half-Cl− solution (apical), and the basolateral membrane was permeabilized with 250 μg/ml amphotericin B. Solutions were bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2 and maintained at 37°C, and short-circuit current was measured on a DVC-1000 voltage clamp (World Precision Instruments Inc., Sarasota, FL) using Ag/AgCl electrodes and 3 M KCl agar bridges.

Patch clamp

Currents were recorded from inside-out membrane patches excised from FRT cells stably expressing TMEM16A. The pipette (extracellular) solution contained (in mM): 150 NaCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 mannitol, 10 Na-Hepes (pH 7.3). The bath (intracellular) solution contained (in mM): 130 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 10 Na-Hepes (pH 7.3), and 8 CaCl2 to obtain the desired free Ca2+ concentration of 305 nM. The electrical resistance of micropipettes was 3–7 MZ. The protocol for stimulation consisted of 600 ms voltage steps in the range from −100 to +100 mV (with 20 mV increments) starting from a holding potential of −60 mV. The interval between steps was 4 s. Membrane currents were filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 5 kHz. Data were analyzed using the Igor software (Wavemetrics, Portland, OR) with custom software kindly provided by Dr. Oscar Moran.

In vitro metabolic stability

Compounds (each 10 uM) were incubated for specific time points (2, 5, 15, 30, 60, 180 min) with shaking at 37 °C with rat liver microsomes (1 mg protein/mL, Sigma- Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM) containing 1 mM NADPH. The mixture was then chilled on ice, and 0.5 mL of ice-cold ethyl acetate was added. Samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 3000 RPM. The supernatant was evaporated to dryness, and the residue was dissolved in 80 μL of mobile phase (acetonitrile:/water, 3:1, containing 0.1% formic acid) for LC/MS. Reverse-phase HPLC separation was carried out using a Waters C18 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 3.5 mm particle size) equipped with a solvent delivery system (Waters model 2690, Milford, MA). The solvent system consisted of a linear gradient from 5% to 95% acetonitrile run over 16 min (0.2 mL/min flow rate).

Plate reader assays of chloride channel function

CFTR inhibition was assayed as described.45 Briefly, FRT cells co-expressing YFP and wildtype CFTR were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then incubated for 15 min with test compounds in PBS containing 20 μM forskolin. I− influx was measured in a plate reader with initial baseline read for 2 s and then for 12 s after rapid addition of an I− containing solution. Activity of non-TMEM16A CaCC was assayed as described28 in HT-29 cells expressing YFP. In each assay initial rates of I− influx were computed as a linear measure of channel function.

Cytotoxicity

FRT cells were cultured overnight in black 96-well Costar microplates and incubated with 5 μM test compounds for 8 h. Cytotoxicity was measured by Alamar Blue assay (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Ex vivo intestinal contractility

Adult mice (CD1 genetic background) were euthanized by avertin overdose (200 mg/kg, 2,2,2-tribromethanol, Sigma-Aldrich) and ileal segments of ~2 cm length were isolated and washed with Krebs-Henseleit buffer (pH 7.4, in mM: 118 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 2.5 CaCl2, 11 D-glucose). The ends of the ileal segments were tied, connected to a force transducer (Biopac Systems, Goleta, CA) and tissues were transferred to an organ chamber (Biopac Systems) containing Krebs-Henseleit buffer at 37°C aerated with 95% O2, 5% CO2. Tissues were stabilized for 60 min with resting tension of 0.5 g and solutions were changed every 15 min. Effects of 10bm on baseline isometric intestinal contractions were recorded. Animal protocols were approved by the UCSF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (approval number: AN108711-02A) and were conducted according with the NIH guidelines for the care and use of animals.

Aqueous stability

Duplicate HPLC samples were prepared in H2O (20% DMSO) containing 10bm (100 μM) and aqueous stable internal standard 5-chloro-3-phenyl-2,1-benzisoxazole (100 μM). The samples were incubated at 25 °C for 3 days, and analyzed daily by ESI-LCMS showing gradual decomposition to the corresponding oxalamic acid.

Aqueous kinetic solubility

To a series of 2 mL aliquots of PBS solution were added increasing quantities of 10bm (30 mM DMSO stock solution). The titration point was determined at 6.5 μL of added stock solution, corresponding to 0.04 mg/ml kinetic solubility.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants R15 GM102874, P30 DK072517, R01 DK099803, R01 DK075302, R01 DK101373, and R01 EY13574, and a grant from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Patch-clamp studies were supported by grants from Ministero della Salute (Ricerca Corrente: Cinque per mille) and Telethon Foundation to LJVG (TMLGCBX16TT). The authors acknowledge Dr. Robert Yen at the SFSU Mass Spectrometry Facility and Dr. Mark Swanson at SFSU NMR Facility.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- AACT

2-acylamino-cycloalkylthiophene-3-carboxylic acid arylamide

- ANO1

anoctamin 1

- CaCC

calcium-activated chloride channel

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator

- DCM

dichloromethane

- 4-DMAP

N,N-dimethylaminopyridine

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- EDCI-HCl

1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride

- FPR

fluorescent plate reader

- FRT

Fischer Rat Thyroid

- PAINS

pan assay interference compounds

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- RT

room temperature

- TLC

thin layer chromatography

- TMEM16A

transmembrane protein 16A

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein

Footnotes

Notes. Drs. Anderson, Phuan and Verkman are named co-inventors on a provisional patent filing with rights owned by UCSF and SFSU.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information Available. Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications Website at DOI: xxxxxxxxx/yyyyyyyyy:

Control measurement of short-circuit current in non-transfected cells; time-course and proposed mechanism of aqueous degradation of inhibitor 10bm; synthesis details and spectroscopic characterization of new molecules (PDF).

Molecular strings for all final inhibitor candidates (CSV).

References

- 1.Pedemonte N, Galietta LJ. Structure and function of TMEM16 proteins (anoctamins) Physiol Rev. 2014;94:419–459. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Picollo A, Malvezzi M, Accardi A. TMEM16 proteins: unknown structure and confusing functions. J Mol Bio. 2015;427:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oh U, Jung J. Cellular functions of TMEM16/anoctamin. Pfluegers Arch. 2016;468:443–453. doi: 10.1007/s00424-016-1790-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qu Z, Yao W, Yao R, Liu X, Yu K, Hartzell C. The Ca2+ -activated Cl− channel, ANO1 (TMEM16A), is a double-edged sword in cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Cancer Med. 2014;3:453–461. doi: 10.1002/cam4.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wanitchakool P, Wolf L, Koehl GE, Sirianant L, Schreiber R, Kulkarni S, Duvvuri U, Kunzelmann K. Role of anoctamins in cancer and apoptosis. Philos Trans R Soc, B. 2014;369:20130096. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guan L, Song Y, Gao J, Gao J, Wang K. Inhibition of calcium-activated chloride channel ANO1 suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis of epithelium originated cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:78619–78630. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Q, Zhi X, Zhou J, Tao R, Zhang J, Chen P, Roe OD, Sun L, Ma L. Circulating tumor cells as a prognostic and predictive marker in gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a prospective study. Oncotarget. 2016;7:36645–36654. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shang L, Hao JJ, Zhao XK, He JZ, Shi ZZ, Liu HJ, Wu LF, Jiang YY, Shi F, Yang H, Zhang Y, Liu YZ, Zhang TT, Xu X, Cai Y, Jia XM, Li M, Zhan QM, Li EM, Wang LD, Wei WQ, Wang MR. ANO1 protein as a potential biomarker for esophageal cancer prognosis and precancerous lesion development prediction. Oncotarget. 2016;7:24374–24382. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu H, Guan S, Sun M, Yu Z, Zhao L, He M, Zhao H, Yao W, Wang E, Jin F, Xiao Q, Wei M. Ano1/TMEM16A Overexpression is associated with good prognosis in PR-positive or HER2-negative breast cancer patients following tamoxifen treatment. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caputo A, Caci E, Ferrera L, Pedemonte N, Barsanti C, Sondo E, Pfeffer U, Ravazzolo R, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ. TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science. 2008;322:590–594. doi: 10.1126/science.1163518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang YD, Cho H, Koo JY, Tak MH, Cho Y, Shim WS, Park SP, Lee J, Lee B, Kim BM, Raouf R, Shin YK, Oh U. TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature. 2008;455:1210–1215. doi: 10.1038/nature07313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schroeder BC, Cheng T, Jan YN, Jan LY. Expression cloning of TMEM16A as a calcium-activated chloride channel subunit. Cell. 2008;134:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrera L, Caputo A, Ubby I, Bussani E, Zegarra-Moran O, Ravazzolo R, Pagani F, Galietta LJ. Regulation of TMEM16A chloride channel properties by alternative splicing. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33360–33368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.046607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tian Y, Kongsuphol P, Hug M, Ousingsawat J, Witzgall R, Schreiber R, Kunzelmann K. Calmodulin-dependent activation of the epithelial calcium-dependent chloride channel TMEM16A. FASEB J. 2011;25:1058–1068. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-166884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tian Y, Schreiber R, Kunzelmann K. Anoctamins are a family of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:4991–4998. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sung TS, O’Driscoll K, Zheng H, Yapp NJ, Leblanc N, Koh SD, Sanders KM. Influence of intracellular Ca2+ and alternative splicing on the pharmacological profile of ANO1 channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2016;311:C437–451. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00070.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu K, Duran C, Qu Z, Cui YY, Hartzell HC. Explaining calcium-dependent gating of anoctamin-1 chloride channels requires a revised topology. Circ Res. 2012;110:990–999. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.264440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tien J, Peters CJ, Wong XM, Cheng T, Jan YN, Jan LY, Yang H. A comprehensive search for calcium binding sites critical for TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channel activity. Elife. 2014;3:e02772. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan H, Gao C, Chen Y, Jia M, Geng J, Zhang H, Zhan Y, Boland LM, An H. Divalent cations modulate TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channels by a common mechanism. J Membr Biol. 2013;246:893–902. doi: 10.1007/s00232-013-9589-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters CJ, Yu H, Tien J, Jan YN, Li M, Jan LY. Four basic residues critical for the ion selectivity and pore blocker sensitivity of TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:3547–3552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502291112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cruz-Rangel S, De Jesus-Perez JJ, Contreras-Vite JA, Perez-Cornejo P, Hartzell HC, Arreola J. Gating modes of calcium-activated chloride channels TMEM16A and TMEM16B. J Physiol. 2015;593:5283–5298. doi: 10.1113/JP271256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fallah G, Romer T, Detro-Dassen S, Braam U, Markwardt F, Schmalzing G. TMEM16A(a)/anoctamin-1 shares a homodimeric architecture with CLC chloride channels. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M110 004697. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.004697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheridan JT, Worthington EN, Yu K, Gabriel SE, Hartzell HC, Tarran R. Characterization of the oligomeric structure of the Ca2+-activated Cl− channel Ano1/TMEM16A. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:1381–1388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.174847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tien J, Lee HY, Minor DL, Jr, Jan YN, Jan LY. Identification of a dimerization domain in the TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channel (CaCC) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:6352–6357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303672110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scudieri P, Musante I, Gianotti A, Moran O, Galietta LJ. Intermolecular interactions in the TMEM16A dimer controlling channel activity. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38788. doi: 10.1038/srep38788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunner JD, Lim NK, Schenck S, Duerst A, Dutzler R. X-ray structure of a calcium-activated TMEM16 lipid scramblase. Nature. 2014;516:207–212. doi: 10.1038/nature13984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jia L, Liu W, Guan L, Lu M, Wang K. Inhibition of calcium-activated chloride channel ANO1/TMEM16A suppresses tumor growth and invasion in human lung cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De La Fuente R, Namkung W, Mills A, Verkman AS. Small-molecule screen identifies inhibitors of a human intestinal calcium-activated chloride channel. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:758–768. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.043208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Namkung W, Phuan PW, Verkman AS. TMEM16A inhibitors reveal TMEM16A as a minor component of calcium-activated chloride channel conductance in airway and intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:2365–2374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.175109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piechowicz KA, Truong EC, Javed KM, Chaney RR, Wu JY, Phuan PW, Verkman AS, Anderson MO. Synthesis and evaluation of 5,6-disubstituted thiopyrimidine aryl aminothiazoles as inhibitors of the calcium-activated chloride channel TMEM16A/Ano1. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2016;31:1362–1368. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2015.1135912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oh SJ, Hwang SJ, Jung J, Yu K, Kim J, Choi JY, Hartzell HC, Roh EJ, Lee CJ. MONNA, a potent and selective blocker for transmembrane protein with unknown function 16/anoctamin-1. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;84:726–735. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.087502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seo Y, Lee HK, Park J, Jeon DK, Jo S, Jo M, Namkung W. Ani9, A novel potent small-molecule ANO1 inhibitor with negligible effect on ANO2. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0155771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis AJ, Shi J, Pritchard HA, Chadha PS, Leblanc N, Vasilikostas G, Yao Z, Verkman AS, Albert AP, Greenwood IA. Potent vasorelaxant activity of the TMEM16A inhibitor T16Ainh -A01. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:773–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun H, Xia Y, Paudel O, Yang XR, Sham JS. Chronic hypoxia-induced upregulation of Ca2+-activated Cl− channel in pulmonary arterial myocytes: a mechanism contributing to enhanced vasoreactivity. J Physiol. 2012;590:3507–3521. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.232520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mroz MS, Keely SJ. Epidermal growth factor chronically upregulates Ca2+- dependent Cl− conductance and TMEM16A expression in intestinal epithelial cells. J Physiol. 2012;590:1907–1920. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.226126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li RS, Wang Y, Chen HS, Jiang FY, Tu Q, Li WJ, Yin RX. TMEM16A contributes to angiotensin II-induced cerebral vasoconstriction via the RhoA/ROCK signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13:3691–3699. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.4979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bill A, Hall ML, Borawski J, Hodgson C, Jenkins J, Piechon P, Popa O, Rothwell C, Tranter P, Tria S, Wagner T, Whitehead L, Gaither LA. Small molecule-facilitated degradation of ANO1 protein: a new targeting approach for anticancer therapeutics. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:11029–11041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.549188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boedtkjer DM, Kim S, Jensen AB, Matchkov VM, Andersson KE. New selective inhibitors of calcium-activated chloride channels - T16AinhA01, CaCCinhA01 and MONNA - what do they inhibit? Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:4158–4172. doi: 10.1111/bph.13201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y, Zhang H, Huang D, Qi J, Xu J, Gao H, Du X, Gamper N. Characterization of the effects of Cl− channel modulators on TMEM16A and bestrophin-1 Ca2+ activated Cl− channels. Pfluegers Arch. 2015;467:1417–1430. doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1572-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Namkung W, Yao Z, Finkbeiner WE, Verkman AS. Small-molecule activators of TMEM16A, a calcium-activated chloride channel, stimulate epithelial chloride secretion and intestinal contraction. FASEB J. 2011;25:4048–4062. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-191627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oh S, Kwon B, Kong S, Yang G, Lee N, Han D, Goo J, Siqueira-Neto JL, Freitas-Junior LH, Liuzzi M, Lee J, Song R. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 2-acetamidothiophene-3-carboxamide derivatives against Leishmania donovani. MedChemComm. 2014;5:142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baell JB, Holloway GA. New substructure filters for removal of pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. J Med Chem. 2010;53:2719–2740. doi: 10.1021/jm901137j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pietra G, Dibattista M, Menini A, Reisert J, Boccaccio A. The Ca2+-activated Cl− channel TMEM16B regulates action potential firing and axonal targeting in olfactory sensory neurons. J Gen Physiol. 2016;148:293–311. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201611622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cherian OL, Menini A, Boccaccio A. Multiple effects of anthracene-9-carboxylic acid on the TMEM16B/anoctamin2 calcium-activated chloride channel. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1848:1005–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tradtrantip L, Sonawane ND, Namkung W, Verkman AS. Nanomolar potency pyrimido-pyrrolo-quinoxalinedione CFTR inhibitor reduces cyst size in a polycystic kidney disease model. J Med Chem. 2009;52:6447–6455. doi: 10.1021/jm9009873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.