Abstract

Photoacoustic tomography (PAT) is an emerging noninvasive biomedical imaging modality that can be used for visualizing the structure and function of brain in high resolution. Here we report an application of PAT to imaging intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) in a mouse model. In vivo photoacoustic images were obtained in mice with right basal ganglia hemorrhage induced by microinjection of collagenase. With multi-spectral light excitation, cortical vascular network was clearly revealed at 532 nm, and ICH associated hematoma lesions and perihemmatoma regions were accurately mapped over time at 750 nm and 875 nm, respectively. Our results suggest that PAT provides a unique tool for visualizing hemodynamics involved in brain diseases such as ICH.

OCIS codes: (170.5120) Photoacoustic imaging, (170.2655) Functional monitoring and imaging

1. Introduction

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is caused by bleeding within the brain tissue itself - a life threatening type of stroke [1–3]. Intracerebral hemorrhage can be caused by hypertension, blood thinner therapy, arteriovenous malformation, aneurism, head trauma, bleeding disorders, tumors, amyloid angiopathy, or drug usage [4]. Over the past four decades, stroke incidence has fallen by about 42% in high-income countries, but increased more than 100% in low to middle income countries [5, 6]. Notably, Asians were reported to have a higher incidence of ICH [7–9]. Surveys showed that the Chinese populations have a higher proportion of ICH in total strokes compared to the white populations of European descent [5, 10–12].

Brain imaging techniques have revolutionized the diagnosis and medical/surgical treatment of ICH by providing the visualization of structural and/or functional information associated with the hematoma lesions and perihematoma. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been used most frequently for ICH assessment [13]. CT is the standard brain imaging study for the initial evaluation of patients with acute hemorrhage. It has high temporal resolution(tens to hundreds of ms) and spatial resolution of traditional CT is 1-2mm [14]. However, CT scans expose patients to radiation, and some patients with minimal blooding remain undetected with CT. MRI serves as an alternative to CT in the detection of acute hemorrhage and is more accurate than CT for the detection of chronic intracerebral hemorrhage. It has a spatial resolution of up to ~1 mm. While MRI is an excellent tool for assessing ICH, it has some limitations including low temporal resolution (~several seconds), and drawn-out imaging time (~several minutes) [15, 16], thus not an ideal tool for monitoring ICH.

Photoacoustic tomography (PAT), a hybrid imaging modality with rich optical contrast and high ultrasound resolution (up to tens of µm spatial resolution and up to tens of ms temporal resolution), shows great potential in various biological and medical applications such as gene expression, vasculature visualization, arthritis diagnosis, brain imaging, and cancer treatment [17–23]. In PAT, after absorbing the incident light energy, chromophores within the tissue, such as hemoglobin, and melanin, will undergo a heat increase. The heat-induced pressure rise will propagate as a kind of acoustic wave in the tissue. PAT produces images by acquiring the acoustic signals around the object, and has the potential to be a powerful technique for visualizing brain hemodynamics and for providing functional information such as hemoglobin and blood oxygenation levels in high spatiotemporal resolution [24–26]. In this study, we present for the first time in vivo results that PAT can be employed to accurately localize and monitor collagenase induced ICH in a mouse model. High resolution PAT images of mice with ICH were obtained at three light wavelengths of 532 nm, 750 nm and 875 nm, and were analyzed in terms of the morphology of hematoma lesions and perihemmatoma regions and their changes over time.

2. Methods

2.1 Experimental animals

A total of eleven male specific pathogen free (SPF) Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) mice (weight = 27-35g) were used in this study. The animal experiments were approved by our Animal Ethics Committee. The body temperature of animal was kept constant at 37 ± 1 °C, which was crucial to minimize the death rate for the experiment. During imaging, the mouse was placed in a custom-made fixation device where the head, tail and limbs were fixated. Ultrasonic coupling agent was applied to the mouse head for maximizing the ultrasound transmission.

2.2 Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) induction

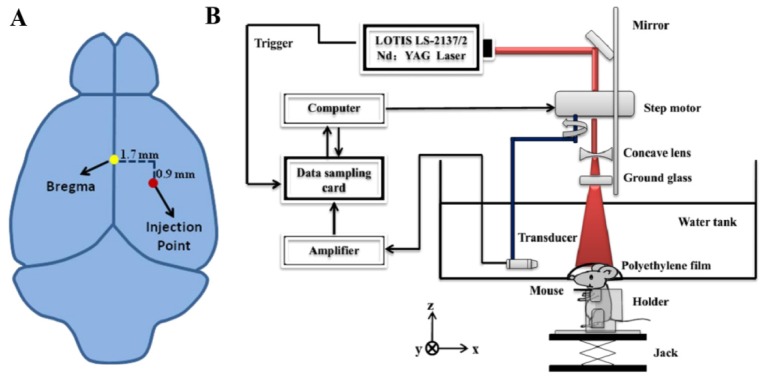

The collagenase induced cerebral hemorrhage model established by Rosenberg has been widely used [27]. Mouse was anesthetized with chloral hydrate by 10% chloral hydrate solution which was injected intraperitoneally to the animal with a dose of 4 ml/kg body weight in all the experiments. Before operation, the hair on the scalp was removed with electric hair clippers and followed with depilatory cream. An incision of 1.5 mm wide in the scalp was made. The skull periosteum was removed using blunt separation. After mounting the animal to a stereotaxis instrument with ear bars, an injection point of collagenase over the right parietal head region was identified accurately (1.7 mm to the right of and 0.9 mm below the bregma, see Fig. 1(a)). Then a hole of 1 mm in diameter was drilled carefully over the injection point with electric cranial drill. Deep intracerebral hemorrhage was caused by bleeding within the deep structures of the brain (thalamus, basal ganglia, pons, and cerebellum). In this study, ICH was induced by microinjection of collagenase into the basal ganglia. Right after the injection of 0.5 µl of 0.15 U/µl collagenase through the hole in the parietal head region, the hole was sealed with bone wax.

Fig. 1.

(a) Schematic showing the location of bregma (yellow dot) and collagenase injection point (red dot). (b) Schematic of our PAT system for in vivo monitoring the collagenase induced intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH).

2.3 Photoacoustic tomography system

A circular-scanning PAT system was used in this study. In this system (Fig. 1(b)), a pulsed Ti:Sapphire laser (LOTIS LS-2137/2) (532 nm and 700-900 nm) with 10ns pulsed duration and 10 Hz pulse repetition rate was used as the excitation source; the energy of pulsed light was controlled below 10 mJ / cm2 at the surface of the animal’s head, which was well below the safety standard (20 mJ/cm2). The laser beam was expanded by a concave lens, uniformly distributed by a ground glass and then delivered to the animal through a water tank with an opening sealed with diaphanous polyethylene film. Ultrasound gel was applied to the animal head for enhanced ultrasound coupling. Upon absorption of light, photoacoustic signals were generated which were detected by a circular-scanning transducer (V310-SU, Olympus) of 5 MHz nominal frequency immersed in the water tank. The bandwidth of the ultrasonic transducer used is 80% (3.5MHz-7.5MHz). The transducer rotated with a radius of 45mm and a step size of 2°, allowing signal collection at 180 locations for one imaging experiment. The scanning time was about 3.5 min. The sampling frequency is 50MHz. The increase of signal-to-noise ratio is proportional to the square root of the averaging times. Since the image quality is proportional to the signal-to-noise ratio, high quality images can accurately show the anatomical structure and pathological conditions including hematoma area. Signal averaging such as ten-time averaging can minimize the unstability of laser energy, and thus the image quality is improved, making the calculation of hematoma area more accurate. However, with the increase in the averaging times, the acquisition time is increased, and the probability of animal activity is also enlarged. Artifacts caused by motion can thus affect the image quality. Therefore, we must be careful in the selection of the averaging times. Ten-time averaging was found to be optimal in our study. A LabVIEW program controlled the PAT system. The spatial resolution of the system is 180µm. At 532nm, rich vasculature was imaged, primarily from the cerebral cortex (as deep as 1-2mm from the scalp), while at both 750 nm and 875 nm, the basal ganglia (as deep as 3-5mm from the scalp) were revealed due to stronger penetration of the near-infrared light [28].

2.4 Reconstruction method

A PAT brain images were reconstructed from photoacoustic signals using a delay and sum reconstruction algorithm [28]. According to the algorithm, we obtained the cerebral deoxyhemoglobin (Hb), oxyhemoglobin (HbO2) and oxygen saturation (sO2) changes of hematoma lesions and perihemmatoma regions at two different wavelengths (750nm and 875nm). It is well known that the absorption coefficient of Hb is higher than that of HbO2 at 750nm, while the absorption coefficient of HbO2 is higher than that of Hb at 875nm [29].

The sO2 changes were calculated pixel by pixel via Eqs. (1) and (2) below, and the pixels were chosen according to the calculated total hemoglobin (HbT) concentration () [28, 30, 31] which should be greater than 0.

| (1) |

| (2) |

where, and are the and concentrations, and are the molar extinction coefficients (cm-1/M), , and are the PA signal amplitude acquired at wavelength 750nm and 875nm, and is the proportionality coefficient which is determined by acoustic parameters and the wavelength-dependent local light fluence. The change of sO2 before and after correction was small [32], so we did not attempt to correct for it. It is worth noting that while due to the unknown coefficient the calculated and values are relative, the sO2 calculated from Eq. (1) is absolute.

2.5 Method for calculating hematoma area

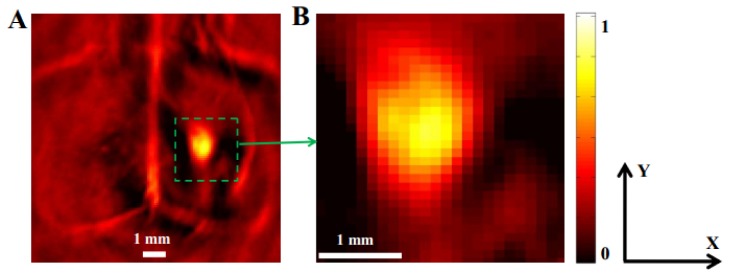

Figure 2 shows the PAT image of an ICH mouse brain at 750nm which was acquired 2 hours post the ICH induction.The entire image area in Fig. 2(a) had 120 pixels along both x and y directions, while the image area in Fig. 2(b) had 30 pixels along both x and y directions (each pixel is a 0.1 mm × 0.1 mm square). A hematoma area is approximately defined as an ellipse measured by its length, and width. Its length and width are then given by calculating the three-quarters-width-at-full-maximum of the image profile (i.e., the pixel value) along the length and width direction of hematoma which is more consistent with the size of hematoma lesion in the brain slices, compared to the global mean value and the half-width-at-full-maximum (HWFM) [28]. The approximation of hematoma as an ellipse is widely used in CT imaging of hematoma [33]. Thus, the hematoma area in our study was calculated as follows:

| (3) |

where a is the length of the hematoma, and b is the width of the hematoma. The measured a and b were 2.4 mm and 1.9 mm, respectively. Thus the Area (ICH) of this mouse was about 3.58 mm2. All the PAT images presented were normalized in scale.

Fig. 2.

In vivo imaging of an ICH mouse brain at 750nm in transverse plane. (A) PAT image acquired 2 hours post the induction of ICH. The hematoma lesion and some background were clearly identified (green square). (B) Close-up view of the area outlined by the green square in Fig. 2(a). Scale bar = 1 mm.

2.6 Statistical analysis

All values are shown as means ± standard error of mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired t-tests. Statistical significance was defined as p ≦ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1 In vivo PAT analyses of hematoma lesion and perihemmatoma regions in ICH mice brains at 750nm

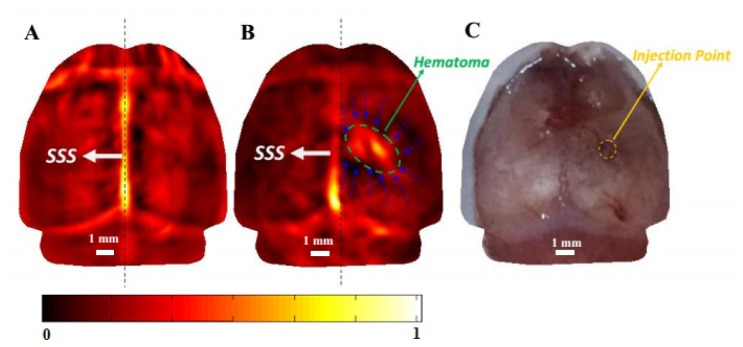

Figures 3(a) and 3(b) present PAT images of a mouse brain at 750nm before and 4 hours after collagenase-induction of ICH, respectively. For this subset of study, a total of four mice were photoacoustically scanned. The vascular network in the left or right hemisphere, the hematoma lesion and the perihemmatoma regions in the layer of basal ganglia were clearly revealed with high contrast and high resolution. The irregular shape and extension of the hematoma were accurately mapped, and the size of the hematoma could be measured to be 3.65 mm (along the X axis) × 2.08 mm (along the Y axis) (Fig. 3(b)). The calculated Area (ICH) for this mouse was 5.96 mm2. After PAT imaging, the mouse was euthanized by an overdose of chloral hydrate. Open-scalp photograph of the mouse brain surface after PAT imaging is shown in Fig. 3(c). The extent of the superficial cerebrovascular distribution in the PAT image (Fig. 3(b)) is in agreement with the open-scalp anatomical photograph (Fig. 3(c)).

Fig. 3.

In vivo imaging of hematoma lesion and perihemmatoma regions in an ICH mouse brain at 750nm (horizontal plane). (A) PAT image of a normal mouse brain before ICH induction. (B) PAT image acquired 4 hours after ICH induction. The hematoma lesion was identified (ellipse in green), and the perihemmatoma regions were also delineated (blue dashed arrows). (C) Open-scalp photograph of the mouse brain surface after the PAT imaging. The injection point was indicated by yellow circle. Dashed line in (A) and (B) indicates the center plane of the brain. Scale bar = 1 mm.

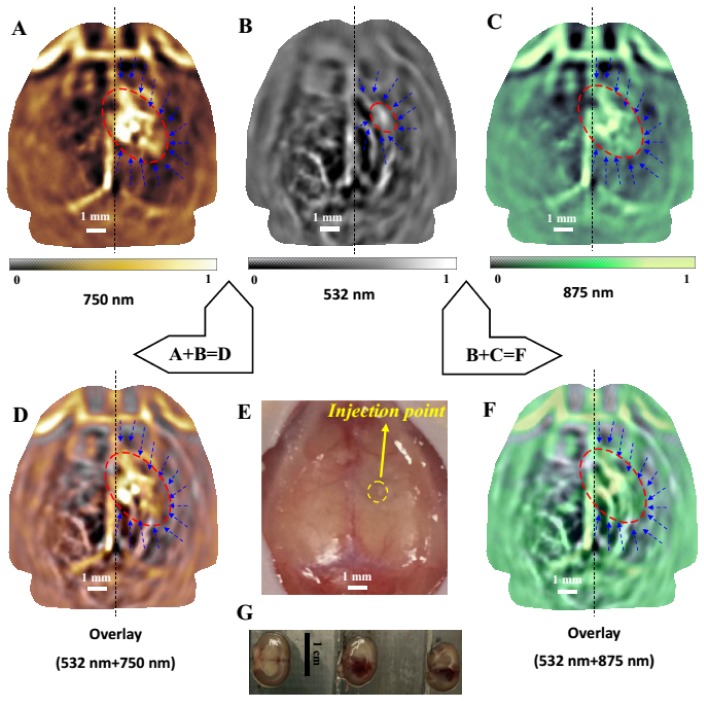

3.2 In vivo multi-spectral PAT analyses of hematoma lesion and perihemmatoma regions in ICH mice brains

Figures 4(a)–4(c) present multi-spectral PAT images of a mouse brain, 18 hours after the induction of ICH, at 532 nm (Fig. 4(b)), 750 nm (Fig. 4(a)) and 875 nm (Fig. 4(c)). With three wavelengths, the mouse brains with ICH were imaged 18 hours after induction. In this time period, the hematoma area reached the maximum and was most stable. Wavelength switching from 532nm to 750nm or 875nm took about 20 minutes. Therefore, we chose to image the mouse 18 hours after induction in order to keep the consistency of the hematoma area at the three wavelengths. In future experiments, if a laser with fast wavelength switching is used, the ICH at three wavelengths can be studied 4 hours after induction. At 532nm, a relatively small hematoma lesion coupled with rich vasculature were imaged, primarily from the cerebral cortex, while at both 750 nm and 875 nm, large hematoma lesions and perihemmatoma regions (indicated by the ellipse in red) were clearly revealed from the deeper layer of basal ganglia due to the strong penetration of the near-infrared light into the hematoma lesions. For this subset of study, a total of three mice were photoacoustically scanned. Figures 4(a) and 4(c) show that the measured size of the hematoma in the deeper layer of basal ganglia was 4.09 mm (a) × 2.55 mm (b) . The calculated Area (ICH) for this mouse was 8.19 mm2. Figure 4(b) show that the measured size of the hematoma in the cerebral cortex was 1.64 mm (a) × 1.09 mm (b). The calculated Area (ICH) for this mouse was 1.40 mm2. Figures 4(d) and 4(f) give the fusions of Figs. 4(a) and 4(b), and Figs. 4(b) and 4(c), respectively. These fused images display the hematoma, perihemmatoma regions, and vascular network from different depths of the brain, in comparison with the open-scalp anatomical photograph shown in Fig. 4(e). Three brain slices (thickness of each slice = 2 mm) were obtained in a coronal plane from the front of the head to the back (see Fig. 4(g)), which confirmed the generation of ICH. We noted that the location and size of hematoma lesion (3.0 mm(along X axis) × 3.9 mm(along Y axis)) nearly matched with that shown in the brain slices (3.1 mm × 4 mm).

Fig. 4.

In vivo imaging of an ICH mouse brain (horizontal plane), 18 hours post the induction of ICH at 532 nm (Fig. 4(b), 750 nm (Fig. 4(a)) and 875 nm (Fig. 4(c)). (d) an overlay of Fig. 4(a) (saffron yellow) over Fig. 4(b) (gray). (e) Open-skull photograph of the mouse brain surface after the imaging experiments. The injection point was indicated by yellow circle. (f) an overlay of Fig. 4(c) (green) over Fig. 4(b) (gray); the cortical vascular network and the hematoma show good colocalization. The hematoma lesion was clearly identified (ellipse in red), and the perihemmatoma regions were ischemia and also revealed (blue dashed arrows). Scale bar = 1 mm for photoacoustic images. (G) Histological photograph of three brain slices in a coronal plane from the front of the head to the back. Scale bar = 1 cm for the photographs of brain slices.

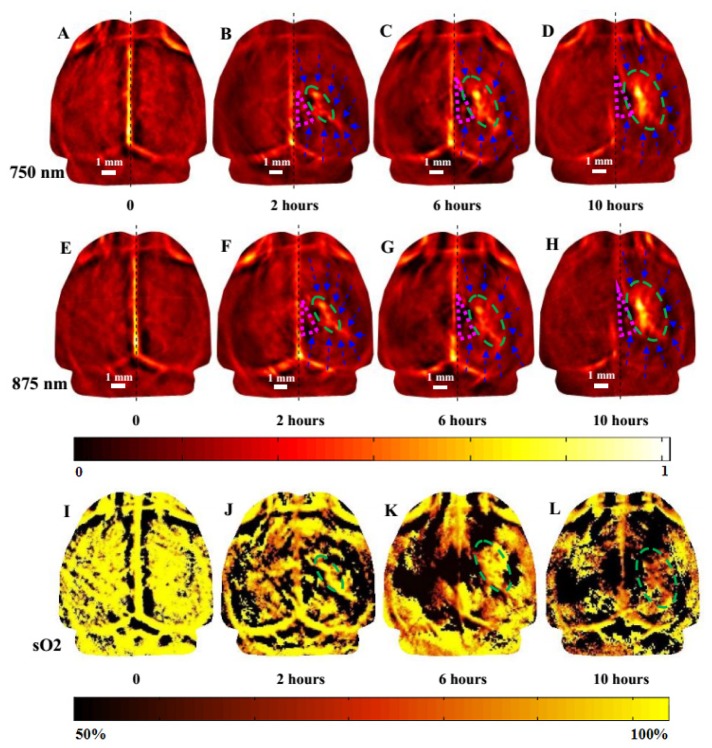

3.3 In vivo monitoring of ICH mice brains by dual-spectral PAT

To further reveal the pathophysiological process of ICH over time, mouse brain was imaged at three time points within 10 hours after the induction of ICH, in addition to a baseline scan. For this subset of study, a total of four mice were photoacoustically scanned. Specifically, each mouse was scanned before ICH induction, and 2 hours, 6 hours, and 10 hours after ICH induction at both 750 nm and 875 nm, and the results from a representative mouse are shown in Fig. 5. Each mouse was imaged four times within 10 hours, and each mouse was anesthetized before each imaging section. Mouse might be dead from repeated anesthetization, so only four key time points were chosen to representatively monitor the pathophysiological process of ICH. From these images, we can see that a series of pathological alterations in response to ICH could be monitored by PAT, including the increase of the hematoma size, hematoma occupying effect, and reduction of cerebral blood flow in the surrounding hemorrhagic area, and reduction of sO2 in the lesion. Within the 10 hours, the hematoma size was gradually increased from 3.16 mm × 1.45 mm (2 hours post ICH) to 4.21 mm × 2.24 mm (6 hours post ICH) and then to 4.74 mm × 2.76 mm (10 hours post ICH) (see Figs. 5(a) – 5(d) for 750 nm and Figs. 5(e) – 5(h) for 875 nm). The calculated Area (ICH) for this mouse was gradually increased from 3.60 mm2 (2 hours post ICH induction) to 10.27 mm2 (10 hours post ICH induction). Within the 10 hours, sO2 in the lesion was gradually declined from 95.37% (before ICH induction) to 89.46% (2 hours post ICH) to 79.70% (6 hours post ICH) and then to 69.41% mm (10 hours post ICH) (see Figs. 5(i)-5(l)).

Fig. 5.

In vivo imaging of an ICH mouse brain (horizontal plane) at 750 nm (a-d) and 875 nm (e-h), and sO2 distribution(i-l), before ICH induction (a, e), 2 hours post ICH induction (b, f), 6 hours post ICH induction (c, g), and 10 hours post ICH induction (d, h). The pink triangle indicates serious local ischemia. The hematoma lesion was clearly identified (ellipse in green), and the perihemmatoma regions were ischemia and also clearly identified (blue dashed arrows). Scale bar = 1 mm.

4. Conclusion and discussion

Literature indicates that hematoma occupying effect could be resulted from ICH, in addition to a series of other pathological alterations such as secondary cerebral edema and reduction of cerebral blood flow in the surrounding hemorrhagic area induced by hematoma compression [34]. It is noted from Fig. 3(b) that the superior sagittal sinus (SSS) moved obviously from the precise middle to the left, indicating a clear local occupying effect. Our results indicated that hematoma occupying effect and reduction of cerebral blood flow in the surrounding hemorrhagic area usually occurred 4 hours post ICH rather than before this period, so the ICH was studied 4 hours after induction for the study of single wavelength of 750 nm illumination.. More specifically, the image after the ICH induction showed that the optical contrast in the perihemmatoma regions became decreased compared with the baseline (i.e., before the ICH induction), which indicates the reduction of cerebral blood flow in the surrounding hemorrhagic area induced by hematoma compression. Multi-spectral (532nm, 750nm and 875nm) image fusion (Fig. 4) allowed us to monitor the expansion of hemorrhage range from basal ganglia to surrounding tissues including the cerebral cortex. Importantly, the cerebral cortex can reflect a lot of functional information, such as the change of motor cortex, the change of cognitive function in ICH mouse.

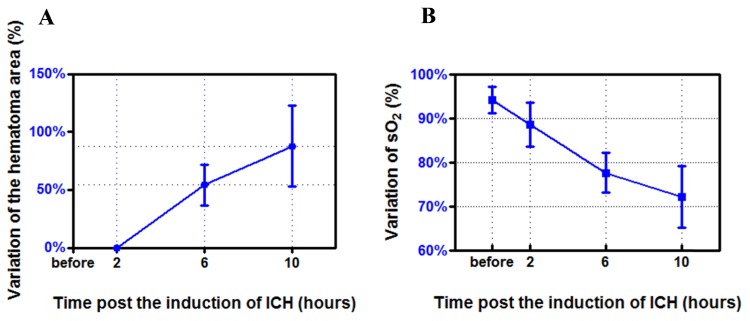

We also note that the change of hematoma morphology was different in the different time periods. During the first 2 hours, the change occurred primarily along the length direction of the hematoma (Figs. 5(b) and 5(f)), while during the rest time period the change happened primarily along the width direction of the hematoma (Figs. 5(c), 5(d), 5(g) and 5(h)). We plotted the percentage variation (SEM) of the hematoma area over time for this subset of study (n = 4) in Fig. 6(a). From 2 hours to 6 hours post ICH induction, the hematoma area was increased by 54.21% ± 17.79%. From 2 hours to 10 hours post ICH induction, the hematoma area was increased by 87.79% ± 34.97%.

Fig. 6.

Histogram of the percentage variation (SEM) of the hematoma area (see Fig. 5(a)) over time (n = 4), from 2 to 10 hours post ICH induction. Histogram of the percentage variation (SEM) of sO2 in the hematoma lesion (see Fig. 5(b)) over time (n = 4): before ICH induction, and 2 to 10 hours post ICH induction. The error bar indicated the standard deviation.

We can observe that local ischemia in the perihemmatoma regions was obvious, due to the low optical absorption in this region (indicated by pink triangle in Fig. 5). This indicates the reduction of cerebral blood flow in this region which likely became ischemic penumbra. In addition, it is noted that the SSS was tilted to the left hemisphere, indicating an obvious local occupying effect. We can also see that the contrast of the SSS was notably lower compared to the baseline images (Figs. 5(a) and 5(e)), which suggests the reduction of cerebral blood flow in the SSS. The penetration of light at 750 nm and 875 nm was similar (as deep as 3-5mm from the scalp). There is a small but crucial difference between the PAT images at 750 nm (Figs. 5(a)–5(d)) and 875nm (Figs. 5(e)–5(h)). Since the absorption of deoxyhemoglobin (Hb) is significantly higher and lower than that of oxyhemoglobin (HbO2) at 750 nm and 875 nm, respectively [29], the PAT images shown in Figs. 5(a)–5(d) and Figs. 5(e)–5(h) reflect the corresponding hemodynamic behavior.

Using Eqs. (1) and (2) we obtained the oxygen saturation (sO2) changes of hematoma lesions based on data collected at two different wavelengths. We note that the change of sO2 in the hematoma lesion was different at different time periods. We plotted the percentage variation (SEM) of sO2 over time for this subset of study (n = 4) in Fig. 6(b). sO2 in the lesion was 94.23% ± 2.97% before ICH induction, while it was decreased to 88.58% ± 5.00%, 77.70% ± 4.54%, and 72.17% ± 7.02% 2 hours, 2-6 hours, and 6-10 hours post ICH induction, respectively. The decrease of sO2 was induced by the increased cerebral deoxyhemoglobin (Hb) and declined cerebral oxyhemoglobin in the hematoma lesion post ICH [35–38].

In sum, we have shown in this work that PAT is capable of noninvasively monitoring the pathophysiological processes of collagenase induced ICH in vivo. Specifically, it can provide morphological changes of hematoma lesions including the hematoma location, shape and size over a long period of time noninvasively. It also allows one to obtain the hemodynamic change of perihemmatoma regions, hematoma occupying effect, and reduction of cerebral blood flow in the surrounding hemorrhagic area induced by hematoma compression. Our results suggest that PAT provides a unique tool for visualizing hemodynamics involved in brain diseases such as ICH. There are limitations in our work. Indeed, many researchers have developed fast photoacoustic (PA) imaging systems. The PLD-PAT system is inexpensive, portable, allows high-speed PAT imaging, and its performance is as good as traditional expensive OPO based PAT system [39–41].

PAT human brain imaging of is limited by the inhomogeneous aberrating effect of the skull. Since the skull attenuates the incident light significantly and scatters ultrasonic waves greatly, the photoacoustic signal decreases sharply. However, based on the unclosed fontanelles, neonatal PAT brain imaging is likely. H. Jiang et al. used PAT in a rat model of epilepsy to demonstrate in vivo reliable tracking of hemodynamic signal with both high spatial and high temporal resolution in 3D [42]. Due to the existence of strong light scattering, a photon recycler could be added to reflect back-scattered light back to the skull, which in turn increased light transmittance through the skull [43].

References and links

- 1.P. V. Patel, L. Elijovich, and J. C. Hemphill III, “Intracerebral Hemorrhage,” in Emergency Neurology, K. L. Roos, ed. (Springer US, 2012), pp. 1274–1278. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broderick J. P., Adams H. P., Jr, Barsan W., Feinberg W., Feldmann E., Grotta J., Kase C., Krieger D., Mayberg M., Tilley B., Zabramski J. M., Zuccarello M., “Guidelines for the Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From a Special Writing Group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association,” Stroke 30(4), 905–915 (1999). 10.1161/01.STR.30.4.905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fewel M. E., Thompson B. G., Jr, Hoff J. T., “Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Review,” Neurosurg. Focus 15(4), 1 (2003). 10.3171/foc.2003.15.4.0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitin S. D., “Hemorrhage - intracerebral (deep),” Cancer (2012).

- 5.Tsai C. F., Anderson N., Thomas B., Sudlow C. L. M., “Comparing Risk Factor Profiles between Intracerebral Hemorrhage and Ischemic Stroke in Chinese and White Populations: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” PLoS One 11(3), e0151743 (2016). 10.1371/journal.pone.0151743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feigin V. L., Lawes C. M., Bennett D. A., Barker-Collo S. L., Parag V., “Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review,” Lancet Neurol. 8(4), 355–369 (2009). 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70025-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feigin V. L., Krishnamurthi R., “Stroke prevention in the developing world,” Stroke 42(12), 3655–3658 (2011). 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.596858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathers C. D., Loncar D., “Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030,” PLoS Med. 3(11), e442 (2006). 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Asch C. J., Luitse M. J., Rinkel G. J., van der Tweel I., Algra A., Klijn C. J., “Incidence, case fatality, and functional outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and ethnic origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” Lancet Neurol. 9(2), 167–176 (2010). 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70340-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai C. F., Thomas B., Sudlow C. L. M., “Differences in the epidemiology of stroke and its subtypes in Chinese populations versus white populations of European origin-systematic review,” Int. J. Stroke 7, 35 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayer S. A., “Intracerebral hemorrhage: natural history and rationale of ultra-early hemostatic therapy,” Intensive Care Med. 28( Suppl 2), S235–S240 (2002). 10.1007/s00134-002-1470-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang X., Liu M., You C., “Advances in classification of intracerebral hemorrhage,” Int. J. Cerebrovase Dis. 21(3), 207–210 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kidwell C. S., Chalela J. A., Saver J. L., Starkman S., Hill M. D., Demchuk A. M., Butman J. A., Patronas N., Alger J. R., Latour L. L., Luby M. L., Baird A. E., Leary M. C., Tremwel M., Ovbiagele B., Fredieu A., Suzuki S., Villablanca J. P., Davis S., Dunn B., Todd J. W., Ezzeddine M. A., Haymore J., Lynch J. K., Davis L., Warach S., “Comparison of MRI and CT for detection of acute intracerebral hemorrhage,” JAMA 292(15), 1823–1830 (2004). 10.1001/jama.292.15.1823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D. Qin, “Overview of MicroCT with Higher Spare Resolution than Normal CT,” China Medical Devices Information (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dizaji A. S., Hamid S. Z., “A Change-point Analysis Method for Single-trial Study of Simultaneous EEG-fMRI of Auditory/Visual Oddball Task,” (2017). 10.1101/100487 [DOI]

- 16.W. Q. Gong, X. F. Tao, and X. Gao, “High Resolution MR Sequence in Detecting Neurovascular Depression,” Military Medical Journal of South China (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bell A. G., “On the production and reproduction of sound by light,” Am. J. Sci. 20(118), 305–324 (1880). 10.2475/ajs.s3-20.118.305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beard P., “Biomedical photoacoustic imaging,” Interface Focus 1(4), 602–631 (2011). 10.1098/rsfs.2011.0028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang J., Xi L., Zhou J., Huang H., Zhang T., Carney P. R., Jiang H., “Noninvasive high-speed photoacoustic tomography of cerebral hemodynamics in awake-moving rats,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 35(8), 1224–1232 (2015). 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu D., Huang L., Jiang M. S., Jiang H., “Contrast Agents for Photoacoustic and Thermoacoustic Imaging: A Review,” Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15(12), 23616–23639 (2014). 10.3390/ijms151223616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taruttis A., Morscher S., Burton N. C., Razansky D., Ntziachristos V., “Fast Multispectral Optoacoustic Tomography (MSOT) for Dynamic Imaging of Pharmacokinetics and Biodistribution in Multiple organs,” PLoS One 7(1), e30491 (2012). 10.1371/journal.pone.0030491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Razansky D., Ntziachristos V., “Multi-Spectral Optoacoustic Tomography: Next Generation Platform for High Resolution Imaging of Diffuse Tissues,” Asia Communications and Photonics Conference and Exhibition IEEE, 1–2 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 23.D. Razansky, and V. Ntziachristos, “High resolution imaging of mouse anatomy and molecular probes in mice by means of multispectral optoacoustic tomography (MSOT),” Photons Plus Ultrasound: Imaging and Sensing Photons Plus Ultrasound: Imaging and Sensing, 82230H–82230H–5 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xi L., Grobmyer S. R., Wu L., Chen R., Zhou G., Gutwein L. G., Sun J., Liao W., Zhou Q., Xie H., Jiang H., “Evaluation of breast tumor margins in vivo with intraoperative photoacoustic imaging,” Opt. Express 20(8), 8726–8731 (2012). 10.1364/OE.20.008726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xi L., Jiang H., “High resolution three-dimensional photoacoustic imaging of human finger joints in vivo,” Appl. Phys. Lett. 107(6), 063701 (2015). 10.1063/1.4926859 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang N., Guo H., Qi W., Zhang Z., Rong J., Yuan Z., Ge W., Jiang H., Xi L., “Whole-body multispectral photoacoustic imaging of adult zebrafish,” Biomed. Opt. Express 7(9), 3543–3550 (2016). 10.1364/BOE.7.003543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenberg G. A., Mun-Bryce S., Wesley M., Kornfeld M., “Collagenase-induced intracerebral hemorrhage in rats,” Stroke 21(5), 801–807 (1990). 10.1161/01.STR.21.5.801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.H. Jiang, Photoacoustic Tomography (CRC Press, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 29.S. Prahl, “Optical Absorption for Hemoglobin,” (Oregon Medical Laser Center, 1999), http://omlc.org /spectra/.

- 30.McBride T. O., Pogue B. W., Gerety E. D., Poplack S. B., Österberg U. L., Paulsen K. D., “Spectroscopic diffuse optical tomography for the quantitative assessment of hemoglobin concentration and oxygen saturation in breast tissue,” Appl. Opt. 38(25), 5480–5490 (1999). 10.1364/AO.38.005480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.H. Jiang, Diffuse Optical Tomography (CRC Press, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maslov K., Zhang H. F., Wang L. V., “Effects of wavelength-dependent fluence attenuation on the noninvasive photoacoustic imaging of hemoglobin oxygen saturation in subcutaneous vasculature in vivo,” Inverse Probl. 23(6), S113–S122 (2007). 10.1088/0266-5611/23/6/S09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan L., Liu H., Li J., “Comparison and application of CT hemotoma volume measurement software with Duotian formula,” Hebei Medical J. 16, 003 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie D., “Treatment of Intracerebral Hemorrhage,” Chin. J. Integr. Med. 1, 6–7 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xi G., Keep R. F., Hoff J. T., “Erythrocytes and delayed brain edema formation following intracerebral hemorrhage in rats,” J. Neurosurg. 89(6), 991–996 (1998). 10.3171/jns.1998.89.6.0991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Auer R. N., Sutherland G. R., “Primary intracerebral hemorrhage: pathophysiology,” Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 32(5 Suppl 2), S3–S12 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karwacki Z., Kowiański P., Witkowska M., Karwacka M., Dziewiatkowski J., Moryś J., “The pathophysiology of intracerebral haemorrhage,” Folia Morphol. (Warsz) 65(4), 295–300 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.C. Rossi and C. Cordonnier, “Pathophysiology of non-traumatic intracerebral haemorrhage,” Oxford Textbook of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Disease (Oxford, 2014), p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Upputuri P. K., Pramanik M., “Performance characterization of low-cost, high-speed, portable pulsed laser diode photoacoustic tomography (PLD-PAT) system,” Biomed. Opt. Express 6(10), 4118–4129 (2015). 10.1364/BOE.6.004118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang J., Xi L., Zhou J., Huang H., Zhang T., Carney P. R., Jiang H., “Noninvasive high-speed photoacoustic tomography of cerebral hemodynamics in awake-moving rats,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 35(8), 1224–1232 (2015). 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang D. W., Xing D., Yang S. H., Xiang L. Z., “Fast full-view photoacoustic imaging by combined scanning with a linear transducer array,” Opt. Express 15(23), 15566–15575 (2007). 10.1364/OE.15.015566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Q., Liu Z., Carney P. R., Yuan Z., Chen H., Roper S. N., Jiang H., “Non-invasive imaging of epileptic seizures in vivo using photoacoustic tomography,” Phys. Med. Biol. 53(7), 1921–1931 (2008). 10.1088/0031-9155/53/7/008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nie L., Cai X., Maslov K., Garcia-Uribe A., Anastasio M. A., Wang L. V., “Photoacoustic tomography through a whole adult human skull with a photon recycler,” J. Biomed. Opt. 17(11), 110506 (2012). 10.1117/1.JBO.17.11.110506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]