Abstract

Urea-based, low molecular weight ligands of glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII) have demonstrated efficacy in various models of neurological disorders and can serve as imaging agents for prostate cancer. To enhance further development of such compounds, we determined X-ray structures of four complexes between human GCPII and urea-based inhibitors at high resolution. All ligands demonstrate an invariant glutarate moiety within the S1′ pocket of the enzyme. The ureido linkage between P1 and P1′ inhibitor sites interacts with the active-site Zn12+ ion and the side chains of Tyr552 and His553. Interactions within the S1 pocket are defined primarily by a network of hydrogen bonds between the P1 carboxylate group of the inhibitors and the side chains of Arg534, Arg536, and Asn519. Importantly, we have identified a hydrophobic pocket accessory to the S1 site that can be exploited for structure-based design of novel GCPII inhibitors with increased lipophilicity.

Introduction

Glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII, E.C. 3.4.17.21) is a type II transmembrane exopeptidase expressed in the nervous system1 where it hydrolyzes endogenous N-acetylaspartyl glutamate (NAAGa) to N-acetylaspartate and glutamate, the latter being the most abundant excitatory neurotransmitter.2 Under normal conditions, glutamate is indispensable for physiological processes such as learning, memory, and developmental plasticity.3 However, excessive glutamate production and release can result in neuronal cell death and is implicated in a variety of neurological conditions including neuropathic/diabetic pain, stroke, trauma, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and schizophrenia.4,5 The upregulation of GCPII expression is also observed in prostate carcinoma and within the neovasculature of solid tumors. The expression of GCPII is confined predominantly to the cell surface, and the enzyme is not extensively shed into the circulation. Therefore, GCPII represents an attractive target for the imaging and therapy of a variety of cancers.6–8

Given the GCPII involvement in a variety of pathologies, discovery and development of GCPII inhibitors as diagnostic or therapeutic agents have been extensively pursued for the last decade (refs 9 and 10 and references therein). GCPII inhibitors reported to date occupy either solely the S1′ (pharmacophore) pocket, or the enzyme-inhibitor interactions can extend over both S1 and S1′ sites. The former type of inhibitor is usually a derivative or mimetic of glutamic acid linked to a zinc-binding group such as phospho(i)nate or thiol, and such inhibitors preferentially bind to the S1′ site of GCPII.11–13 The latter group encompasses analogues of dipeptides (such as NAAG, the natural GCPII substrate) with the peptide bond substituted by a hydrolysis-resistant surrogate.14–17 Among others, this category includes dipeptide analogues connected by a urea linkage, previously developed by us.18,19 The relative ease of synthesis of the urea-based inhibitors of GCPII facilitates SAR studies. Furthermore, compared to the similar phosphinates, the urea derivatives are less polar and thus better suited for applications requiring increased lipophilicity of inhibitors such as stroke therapy. The efficacy of the urea-based compounds has been demonstrated in various animal models of neurological disorders.19–23 Additionally, radiolabeled derivatives were successfully applied for in vivo imaging in experimental models of prostate cancer as well as for in vitro identification of GCPII in rodent and human brains.24–26

The extracellular catalytic portion of GCPII (amino acids 44–750) consists of three structurally distinct domains, each of them contributing residues implicated in substrate binding.27 The S1′ (pharmacophore) pocket accepts the C-terminal part of a substrate/inhibitor and preferentially binds glutamate or glutamate-like moieties. The most prominent feature of the S1 pocket in GCPII is the “arginine patch”, comprising arginines 463, 534, and 536, which is mainly associated with the enzyme’s preferences for negatively charged P1 residues of the ligand. 11,27–30 Compared to the S1′ site, the S1 pocket is more flexible in terms of structural modifications of the GCPII inhibitors.14,16,19

Recently, we have reported several high-resolution structures of the GCPII ectodomain in complex with small-molecule ligands such as mimetics and derivatives of glutamic acid as well as phosphinate-based analogues of acidic dipeptides.11,29 These structures advanced our understanding of the architecture of the GCPII active site but did not reveal the complete picture of GCPII–inhibitor interactions. First, out of a variety of zincbinding groups utilized for the design of GCPII inhibitors, only phospho(i)nates have so far been successfully co-crystallized with GCPII.11,27,29 Furthermore, lack or limited variability of the P1 side chains in inhibitors studied previously hampers detailed analysis of the S1 site. Also, this lack of variability limits a structure-based design of new GCPII inhibitors by overlooking the advantage of modifications in the P1 position that might provide higher affinity interaction with the enzyme.

This manuscript aims to extend our understanding of interactions between human GCPII and low molecular weight ligands. We describe the first detailed structures of complexes between human GCPII and urea-based inhibitors. Our data provide an explanation for earlier SAR studies, offer a deeper insight into both the architecture of the S1 pocket and enzyme–inhibitor interactions, and form the basis for the structure-aided design and development of the next generation of dipeptide-based GCPII inhibitors and substrates.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of Inhibitors

Urea-based inhibitors with which GCPII crystal complexes were determined in this study include (S)-2-(3-((R)-1-carboxy-2-methylthio)ethyl)ureido)pentanedioic acid (1, DCMC in Figure 1), (S)-2-(3-((S)-1-carboxy- 2-(4-hydroxy-3-iodophenyl)ethyl)ureido)pentanedioic acid (2, DCIT in Figure 1), (S)-2-(3-((R)-1-carboxy-2-(4-fluorobenzylthio) ethyl)ureido)pentanedioic acid (3, DCFBC in Figure 1), and (S)-2-(3-((S)-1-carboxy-(4-iodobenzamido)pentyl)ureido)pentanedioic acid (4, DCIBzL in Figure 1). All four inhibitors were stereochemically pure and can be viewed as nonhydrolyzable analogues of NAAG, with the N-acetylaspartate moiety replaced by four different side chains. Common features of these compounds are (a) the ureido linkage substituting for the peptide bond of a parental dipeptide, and (b) the C-terminal glutarate moiety (Figure 1). The synthesis of 1 has been reported previously.18 Our synthesis of 1 differs from the previous protocol by the use of p-methoxybenzyl esters as protecting groups instead of benzyl esters. Preparation of 2 is different from that used to prepare [125I]2,24 where the radioiodine is added in the last step of the radiosynthesis. Experimental details and analytical data of 1 and 2 are described in the Supporting Information. Compounds 3 and 4 were prepared as described previously.31,32 Compounds 1, 2, and 3 are potent inhibitors of GCPII, with IC50 values of 17, 0.5, and 14 nM, respectively.24,32,33 Compound 4 is even more potent with an IC50 value of 0.06 nM.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of NAAG and urea-based GCPII inhibitors.

Overall Structural Comparison

Structures of rhGCPII/2, rhGCPII/1, rhGCPII/3, and rhGCPII/4 complexes were determined by difference Fourier methods and refined at the resolutions of 1.54, 1.75, 1.69, and 1.55 Å, respectively (Table 1). The orientation of the individual inhibitors in the rhGCPII active site was unequivocally identified from the positive density peaks in the Fo−Fc omit maps (Supporting Information, Figure S1) with the invariant C-terminal glutamate facing the S1′ pocket of the enzyme and variable positioning of the P1 moieties. All four complexes of rhGCPII share common fold, with the rootmean-square deviations between 0.32 and 0.52 Å for ~695 equivalent Cα-atoms in any two complexes compared.

Table 1.

Data Collection and Refinement Statistics

| rhGCPII/1 | rhGCPII/2 | rhGCPII/3 | rhGCPII/4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection Statistics | ||||

| wavelength (Å) | 1.000 | |||

| temperature (K) | 100 | |||

| space group | I222 | |||

| unit cell parameters a, b, c (Å) | 101.8, 129.7, 159.3 | 101.4, 130.0, 158.5 | 101.9, 130.5, 159.2 | 101.3, 130.5, 158.7 |

| resolution limits (Å) | 30–1.75 (1.81–1.75) a | 30–1.54 (1.60–1.54) | 30–1.69 (1.75–1.69) | 30–1.55 (1.61–1.55) |

| number of unique reflections | 105078 (10129) | 144557 (9835) | 116666 (11057) | 143433 (9756) |

| redundancy | 6.8 (5.2) | 6.1 (4.0) | 6.5 (4.5) | 7.1 (4.5) |

| completeness (%) | 99.6 (96.9) | 95.0 (65.3) | 99.5 (95.3) | 94.6 (64.9) |

| I/σI | 21.5 (2.4) | 17.6 (2.2) | 14.8 (2.3) | 21.4 (2.2) |

| Rmerge | 0.070 (0.49) | 0.071 (0.43) | 0.094 (0.51) | 0.068 (0.43) |

| Refinement Statistics | ||||

| resolution limits (Å) | 15.0–1.75 (1.79–1.75) | 15.0–1.54 (1.58–1.54) | 15.0–1.69 (1.74–1.69) | 15.0–1.55 (1.59–1.55) |

| no. of reflections | 103375 (6801) | 142946 (6620) | 114765 (7473) | 141846 (6804) |

| no. of reflections in test set | 1550 (111) | 1446 (66) | 1730 (97) | 1445 (76) |

| R | 0.170 (0.252) | 0.177 (0.279) | 0.179 (0.255) | 0.183 (0.270) |

| Rfree | 0.204 (0.272) | 0.195 (0.276) | 0.199 (0.293) | 0.208 (0.290) |

| [0.155 (0.226)] b | [0.161 (0.213)] | |||

| [0.179 (0.254)] | [0.190 (0.257)] | |||

| total number of non-H atoms | 6552 | 6603 | 6580 | 6529 |

| number of ligand atoms | 21 | 26 | 28 | 31 |

| number of ions | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| number of water molecules | 617 | 657 | 626 | 592 |

| average B-factor (Å2) | ||||

| protein atoms | 26.4 | 25.7 | 26.8 | 27.9 |

| waters | 38.7 | 38.6 | 38.4 | 39.6 |

| inhibitor | 24.5 | 25.7 | 26.8 | 25.4 |

| rms deviations | ||||

| bond lengths (Å) | 0.021 | 0.018 [0.015] | 0.020 | 0.018 [0.015] |

| bond angles (deg) | 1.92 | 1.78 [1.60] | 1.79 | 1.74 [1.57] |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | ||||

| most favored | 90.3 | 89.2 | 89.7 | 89.3 |

| additionally allowed | 9.2 | 10.2 | 9.8 | 10.0 |

| generously allowed | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| disallowed | 0.2 (Lys207) | 0.2 (Lys207) | 0.2 (Lys207) | 0.2 (Lys207) |

| missing residues | 44–-54, 541–543, 654–655 | 44–54, 545–-547, 654–655 | 44–54, 654–655 | 44–54, 654–655 |

Values in parentheses correspond to the highest resolution shells.

Values in brackets correspond to refinement utilizing the anisotropic model for B-factors.

The S1′ Pocket

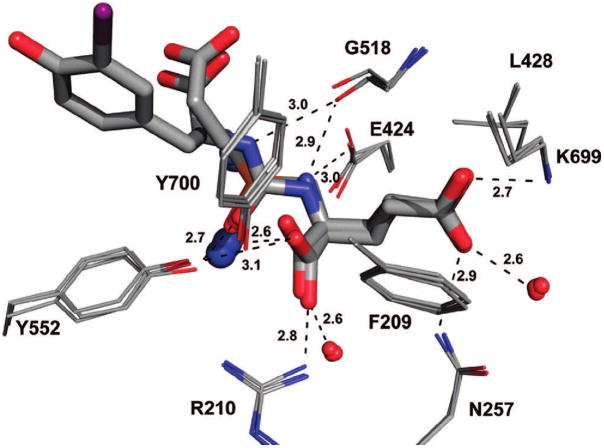

The S1′ site of human GCPII has strong preference for glutamate or glutamate-like residues.28,34 Consistent with this observation, the S1′ pocket is occupied by the invariant glutamate of the urea inhibitors. The α-carboxylate group of glutamate of the inhibitor forms strong H-bonds with the guanidinium group of Arg210 (2.8 Å; distances present here are from rhGCPII/2, the complex refined at the highest resolution) and the hydroxyl group of Tyr552 (3.1 Å), and the γ-carboxylate is engaged by the side chains of Asn257 (Nδ2, 2.9 Å) and Lys699 (Nζ, 2.7 Å). The shape of the S1′ pocket is defined by Gly518 and the side chains of Phe209 and Leu428, which also contribute nonpolar interactions to the inhibitor binding. Additional stabilization of inhibitor is contributed by the water interactions of α- and γ-carboxylate groups. The overall architecture of the S1′ pocket, position of the C-terminal glutamate, and the enzyme–inhibitor interactions are virtually identical to those observed for complexes of rhGCPII with free glutamate and phospho(i)nate analogues of glutamate/NAAG11,27,29 (Figure 2). Evidently, the S1′ pocket is “optimized” for glutamate binding and glutamate-like residues are the best choice as to be positioned at the C-terminus of GCPII inhibitors. Our structural observations are fully supported by available SAR studies showing low tolerance for substitutions at the P1′ position of the inhibitors.14,16,19

Figure 2.

Structural similarity of the glutamate binding in the S1′ pocket. The X-ray structures of rhGCPII/EPE (PDB code 3bi0), rhGCPII/glutamate complex (PDB code 2c6g), and the rhGCPII/2 complexes are superimposed using corresponding Cα-atoms. The active site ligands are in stick representation, residues shaping the S1′ pocket are shown as lines, Zn2+ ions as blue spheres, and conserved water molecules as red spheres. The H-bonds are indicated by dashed lines with distances shown in Ångstroms (from the rhGCPII/2 complex).

The Ureido Linkage

The ureido group of the inhibitors mimics a planar peptide bond of a GCPII substrate, such as NAAG, but acts as an amide-bioisostere due to its resistance to hydrolysis by the enzyme.35 In the structures reported here, the ureido carbonyl oxygen is engaged by the side chains of Tyr552 (OH, 2.7 Å) and His553 (Nε2, 3.2 Å), and further interacts with the activated water molecule (2.8 Å) and the Zn12+ ion (2.6 Å). The N2 is H-bonded to the Glu424 γ-carboxylate (3.0 Å), Gly518 carbonyl oxygen (2.9 Å), and the activated water molecule (3.1 Å), while the second ureido nitrogen donates only one H-bond to the Gly518 main-chain carbonyl (3.0 Å).

It is interesting to note that the active-site arrangement of the rhGCPII–ureido complexes mirrors the situation in the rhGCPII(E424A)/NAAG complex (Barinka, unpublished) with the distance between the two active-site zinc ions ~3.3 Å and the activated water molecule positioned symmetrically in between them (2.0 Å). This finding validates the prediction of the urea biostere as a true surrogate of the peptide bond.

The S1 Site and an “Accessory Hydrophobic Pocket”

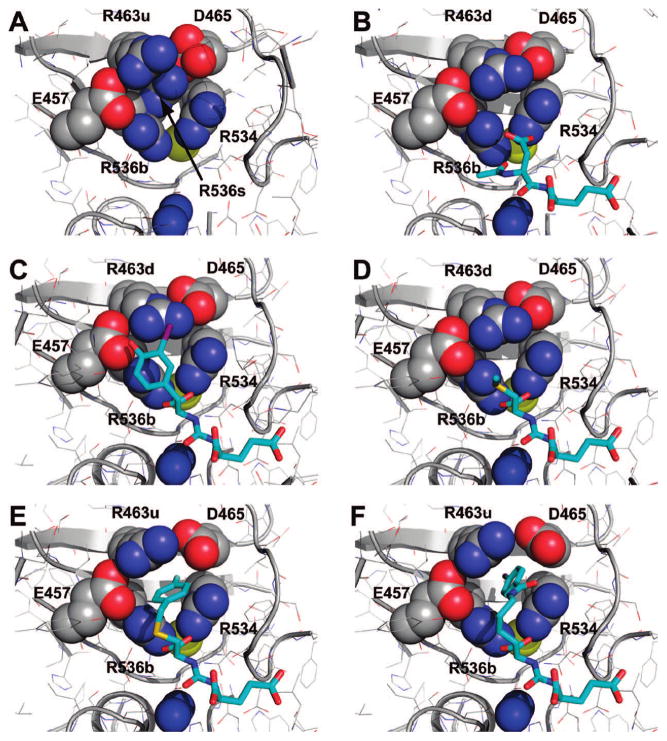

The major structural signature of the S1 pocket of the enzyme is the “arginine patch” comprising arginines 463, 534, and 536.29,30 The Arg534 is kept in an invariant position via its interaction with the S1-bound chloride anion, but both Arg536 and, to a lesser extent Arg463, are quite flexible. The Arg536 side chain can adopt two distinct conformations referred to as “stacking” and “binding,” and transition between these two states is associated with shift of the Arg463 side chain between “up” and “down” positions, respectively (Supporting Information, Figure S2). Such flexibility likely contributes toward less stringent substrate specificity within the S1 site of the enzyme (in comparison to the S1′ site) and also modulates affinity of P1 diversified GCPII inhibitors.28,29,36

While the C-terminal glutamate and the ureido group of all four inhibitors structurally overlap, there are considerable positional differences within the S1 pocket of the enzyme (Figure 3A). The only common denominator of the S1 sites in four complexes is the engagement of the P1 carboxylate in four direct contacts with the side chains of Asn519 (Nδ, 2.9 Å), Arg534 (Nη1, 2.9 Å) and Arg536 (Nη1, 2.9 Å; Nη2, 3.0 Å) and two water mediated polar interactions (2.8 and 2.7 Å; Figure 3B). Hydrogen bonds between the P1 carboxylate and the guanidinium group of Arg536 stabilize the latter in its “binding” conformation in a manner similar to the binding of NAAG. Because the P1 carboxylate of the studied urea-based compounds contributes prominently to the GCPII–inhibitor interactions in the S1 pocket, it is reasonable to suggest that this structural feature should be preserved in future generations of such inhibitors to retain high-affinity binding for GCPII.

Figure 3.

(A) Superposition of urea-based inhibitors in the active-site of rhGCPII. The rhGCPII–inhibitor complexes were superimposed on corresponding Cα-atoms. The inhibitors are shown in stick representation and protein residues are shown as lines. Note invariant positioning of the P1′ glutamate contrasting with inhibitor conformational variability in the S1 pocket. (B) Hydrogen-bonding network in the S1 site of GCPII. Hydrogen bonding interactions (indicated with dashed lines) and distances (in Ångstroms) between 1 bound in the active site and S1 residues of GCPII. The zinc ions, chloride anion, and water molecules located in the active site are shown as blue, yellow and red spheres, respectively. The protein and inhibitor atoms are colored red (oxygen), blue (nitrogen), yellow (sulfur), violet (iodine), cyan (fluorine), gray (carbons).

The P1 methylcysteine side chain of 1 is placed into a “hydrophobic section” of the S1 pocket, defined by the sidechains of Tyr549, Tyr552, and Tyr700, but its fit is rather loose with no signature interactions observed. A similar conclusion can be drawn for the P1 side chain of 2, with the exception of H-bonds between the P1 hydroxyl group and side-chains of Glu457 (Oε1, 2.6 Å) and Arg463 (Nη2, 3.2 Å). Each of 2, 3, and 4 feature a phenyl ring as a terminal part of their P1 side chain but they differ in the length of a linker connecting the ring to the ureido group (Figure 1). The linker in 2 consists of only one methylene group, while those in 3 and 4 feature equivalents of three and six methylene groups, respectively (Figure 1). Consequently, the phenyl groups of 3, and especially of 4, have more positional freedom and could extend further into the S1 pocket.

Given the positional freedom of the terminal phenyl ring of 3, it is interesting to find it partially inserted into a pocket accessory to the S1 site with approximate dimensions of 8.5 Å × 7 Å × 9 Å. The bottom of this hydrophobic “accessory pocket” is defined by portions of β-sheets β13 (Arg463–Asp465) and β14 (Arg534–Arg536), while the walls are shaped by the side chains of Glu457, Arg463, Asp465, Arg534, and Arg536 (Figure 4). The formation of such a pocket is only possible by simultaneous “atypical” positioning of Arg536 into the “binding” configuration and Arg463 into the “up” position. On the contrary, when NAAG, the natural GCPII substrate, is bound in the active site of the enzyme, the Arg536 side chain is stabilized in the “binding” conformation, but Arg463 relocates by 2 Å into the “down” position at the same time, effectively closing the “accessory pocket.” Similarly, under conditions when the S1 site is unoccupied or is occupied by a moiety that fails to enforce the Arg536 “binding” conformation, the Arg536 side chain is found in both “binding” and “stacking” alternate positions (accompanied by the “down” and “up” position of Arg463, respectively) resulting in closure (disappearance) of the “accessory pocket” (Figure 5). In the case of 4, the phenyl ring is fully inserted into the pocket (due to presence of longer P1 spacer), and this fact likely contributes to the tighter inhibitor binding that is translated into an IC50 value of ~10-fold lower as compared to 2 and 3.

Figure 4.

The hydrophobic pocket accessory to the S1 site. The dissected substrate-binding cavity of GCPII is shown in semitransparent surface representation (gray). The side chains of amino acids delineating the “accessory hydrophobic pocket” are shown in stick representation and colored cyan. The active-site Zn2+ and S1-bound Cl− are colored blue and yellow, respectively, and water molecules are represented by red spheres. Compound 4 bound to the active site is in stick representation.

Figure 5.

The flexibility of S1 arginines 463 and 536 defines size of the “accessory pocket”. Dissected view into the active-site of GCPII. The protein moiety is shown in combination of cartoon and line representation. The residues shaping walls of the accessory pocket are shown as spheres and inhibitor (substrate) residues are in stick representation. The active site Zn2+ and S1 bound Cl− are colored blue and yellow, respectively. The R463u and R463d denotes the side chain of Arg463 in the “up” and “down” position, respectively, while R536b and R536s denotes the side chain of Arg536 in the “binding” and “stacking” configuration, respectively. Notice the closure of the accessory pocket in the unliganded GCPII structure (A). Shown are complexes of rhGCPII with 2 (C), 1 (D), 3 (E), and 4 (F). The complex between the E424A active-site mutant of GCPII and NAAG, the GCPII natural substrate, is included for comparison (PDB code 3bxm, (B)).

The existence of such “remote hydrophobic binding register” has been predicted in the study by Berkman’s group, where the authors showed that lengthening of the methylene linker between the phosphoamidate surrogate and the terminal phenyl group results in stronger inhibitor binding to GCPII.15 Clearly, the incorporation of a longer spacer into the P1 side chain allows for the full insertion of the phenyl ring into the accessory hydrophobic pocket with concomitant decrease in inhibition constants. Our observations thus provide a structural rationale for Berkman’s inhibition data and further underscore the importance of Arg463 and Arg536 flexibility in influencing the affinity of various inhibitors to GCPII.29

Thermal displacement parameters for the P1 moieties of the inhibitors are considerably higher (6.3–15.0 Å2) when compared to the corresponding C-termini (Supporting Information, Figure S3). This observation is consistent with site-directed mutagenesis studies, SAR data, and findings reported for the X-ray structures of GCPII and phosphinate-based inhibitors.14–17,19,29,37 Clearly, the C-terminal glutamate or glutamate-like residue contributes prominently to the inhibitor affinity towards GCPII, while the P1 moiety is less important in this respect. Concurrently, however, the hydrophobic pocket accessory to the S1 site identified here could be exploited for further optimization of GCPII inhibitors by modification of the P1 moiety. The appendage of a hydrophobic functionality (with the linker of the appropriate length) at the P1 position can both enhance inhibitor affinity towards GCPII and increase liphophilicity of such compounds as a first step toward facilitating blood–brain barrier penetration, if desired.

Conclusions

We determined high-resolution structures of human GCPII and four urea-based inhibitors and identified a hydrophobic pocket accessory to the S1 specificity site. Our data provide a mechanistic explanation for prior SAR studies on GCPII inhibitors and can serve as a useful platform for the design of novel GCPII inhibitors with improved pharmacokinetic properties.

Experimental Section

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Human GCPII (rhGCPII)

Human GCPII (the extracellular part, amino acids 44–750) was heterologously overexpressed in Drosophila Schneider’s S2 cells and purified to homogeneity as described previously.28 This construct is designated rhGCPII (recombinant human GCPII). The final protein preparation in 20 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.0 was concentrated to 8 mg/mL and stored at −80°C until further use.

Crystallization and X-ray Data Collection

The inhibitors were dissolved in distilled water to a final concentration of 40 mM, and the pH of the solution was adjusted to 8.0 with 1 M NaOH. The rhGCPII stock solution (8 mg/mL) was mixed with 1/10 v/v of the individual inhibitor, and the complexes were crystallized using the hanging drop vapor diffusion setup at 293 K. Crystallization droplets were made by combining 1 μL of the rhGCPII–inhibitor mixture and 1 μL of the reservoir solution containing 33% pentaerythriol propoxylate (PO/OH 5/4; Hampton Research), 1% PEG3350, and 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. Crystals belonging to the space group I222 typically appeared within two days and reached their final size with approximate dimensions of 0.3 mm × 0.4 mm × 0.1 mm within a week. For data collection crystals were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen directly from the reservoir solution, and diffraction intensities were collected at 100 K using synchrotron radiation at the SER-CAT sector 22 beamlines of the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne, IL) at the X-ray wavelength of 1.0 Å. In all cases, the diffraction data were collected from a single crystal, recorded on a CCD detector, and processed using the HKL2000 software package.38

Structure Determination and Refinement

Structures of rhGCPII/inhibitor complexes were determined by difference Fourier methods using the coordinates of unliganded rhGCPII (PDB code 2oot) as a starting model.30 Refinement calculations were performed with Refmac 5.139 and manual rebuilding of the models was carried out using the program Xfit.40 Approximately 1% (corresponding to 1445–1730 reflections) of the data were selected to monitor the progress of the refinement by calculating Rfree. The inhibitor moieties were easily modeled in strong positive Fo−Fc electron density observed at the expected place in the substrate binding cavity of rhGCPII. At the later stages of refinement, the mixed anisotropic/isotropic refinement protocol was employed with the anisotropic model of the displacement parameters (B-factors) applied to “heavy atoms” (i.e., I, S, Zn2+, Ca2+, and Cl−) of all complexes. Additionally, we used the fully anisotropic refinement model for rhGCPII/2 and rhGCPII/4, the two complexes with the highest resolution data. The anisotropic refinements resulted in better refinement statistics, including lower R and Rfree and more favorable model geometry (Table 1). At the same time, root mean square deviations between corresponding models refined with the mixed anisotropic/isotropic versus anisotropic protocols were 0.16 Å for each of rhGCPII/2 and rhGCPII/4 complexes, suggesting virtual identity of the final models. Despite of improving the stereochemistry of the structures and their agreement with experimental data, an implementation of the anisotropic refinement of B-factors did not result in additional information. Because with ~2.4 experimental data per parameter refined, there is a possibility of the model being “over-refined” using the fully anisotropic protocol. Accordingly, we based our subsequent structure analysis on models refined in the mixed anisotropic/isotropic mode. The quality of the final models was assessed with the program PROCHECK.41 The data collection and refinement statistics are listed in Table 1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of Dr. Jan Konvalinka during early stages of this project. Diffraction data were collected at the South-East Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) beamline 22-ID, at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under contract no. W-31-109-Eng38. This project was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research (J.L.) and NIH grants CA92871, CA1114111, CA111982, EB005423, and MH080580 and Department of Defense grant PC050825 (M.G.P.).

Footnotes

PDB accession numbers. Atomic coordinates of the present structures together with the experimental diffraction amplitudes have been deposited at the RCSB Protein Data Bank with accession numbers 3D7G (the complex with 1, (DCMC)), 3D7F (the complex with 2, (DCIT)), 3D7D (the complex with 3, (DCFBC)), and 3D7H (the complex with 4, (DCIBzL)).

Abbreviations: rhGCPII, recombinant human glutamate carboxypeptidase II; DCIT, (S)-2-(3-((S)-1-carboxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3-iodophenyl)ethyl) ureido)pentanedioic acid; DCMC, (S)-2-(3-((R)-1-carboxy-2-methylthio- )ethyl)ureido)pentanedioic acid; DCFBC, (S)-2-(3-((R)-1-carboxy-2-(4-fluorobenzylthio)ethyl)ureido)pentanedioic acid; DCIBzL, (S)-2-(3-((S)-1- carboxy-(4-iodobenzamido)pentyl)ureido)pentanedioic acid; NAAG, N-acetylaspartylglutamate; SAR, structure-activity relationship.

Supporting Information Available: Density maps of the substrate binding cavity of human GCPII in complex with 3, 2, 1, and 4; flexibility of S1 Arg463 and Arg536; thermal displacement parameters of urea-based inhibitors; experimental procedures and analytical data for all intermediates of 1 and 2. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Sacha P, Zamecnik J, Barinka C, Hlouchova K, Vicha A, Mlcochova P, Hilgert I, Eckschlager T, Konvalinka J. Expression of glutamate carboxypeptidase II in human brain. Neuroscience. 2007;144:1361–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neale JH, Bzdega T, Wroblewska B. N-Acetylaspartylglutamate: the most abundant peptide neurotransmitter in the mammalian central nervous system. J Neurochem. 2000;75:443–452. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riedel G, Platt B, Micheau J. Glutamate receptor function in learning and memory. Behav Brain Res. 2003;140:1–47. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00272-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doble A. The role of excitotoxicity in neurodegenerative disease: implications for therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 1999;81:163–221. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meldrum BS. Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the brain: review of physiology and pathology. J Nutr. 2000;130:1007S–1015S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.4.1007S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bostwick DG, Pacelli A, Blute M, Roche P, Murphy GP. Prostate specific membrane antigen expression in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and adenocarcinoma: a study of 184 cases. Cancer. 1998;82:2256–2261. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980601)82:11<2256::aid-cncr22>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang SS, O’Keefe DS, Bacich DJ, Reuter VE, Heston WD, Gaudin PB. Prostate-specific membrane antigen is produced in tumor-associated neovasculature. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2674– 2681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinoshita Y, Kuratsukuri K, Newman N, Rovito PM, Kaumaya PT, Wang CY, Haas GP. Targeting epitopes in prostate-specific membrane antigen for antibody therapy of prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2005;8:359–363. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsukamoto T, Wozniak KM, Slusher BS. Progress in the discovery and development of glutamate carboxypeptidase II inhibitors. Drug Discovery Today. 2007;12:767–776. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou J, Neale JH, Pomper MG, Kozikowski AP. NAAG peptidase inhibitors and their potential for diagnosis and therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2005;4:1015–1026. doi: 10.1038/nrd1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barinka C, Rovenska M, Mlcochova P, Hlouchova K, Plechanovova A, Majer P, Tsukamoto T, Slusher BS, Konvalinka J, Lubkowski J. Structural insight into the pharmacophore pocket of human glutamate carboxypeptidase II. J Med Chem. 2007;50:3267– 3273. doi: 10.1021/jm070133w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson PF, Cole DC, Slusher BS, Stetz SL, Ross LE, Donzanti BA, Trainor DA. Design, synthesis, and biological activity of a potent inhibitor of the neuropeptidase N-acetylated alphalinked acidic dipeptidase. J Med Chem. 1996;39:619–622. doi: 10.1021/jm950801q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Majer P, Jackson PF, Delahanty G, Grella BS, Ko YS, Li W, Liu Q, Maclin KM, Polakova J, Shaffer KA, Stoermer D, Vitharana D, Wang EY, Zakrzewski A, Rojas C, Slusher BS, Wozniak KM, Burak E, Limsakun T, Tsukamoto T. Synthesis and biological evaluation of thiol-based inhibitors of glutamate carboxypeptidase II: discovery of an orally active GCP II inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2003;46:1989–1996. doi: 10.1021/jm020515w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson PF, Tays KL, Maclin KM, Ko YS, Li W, Vitharana D, Tsukamoto T, Stoermer D, Lu XC, Wozniak K, Slusher BS. Design and pharmacological activity of phosphinic acid based NAALADase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2001;44:4170–4175. doi: 10.1021/jm0001774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maung J, Mallari JP, Girtsman TA, Wu LY, Rowley JA, Santiago NM, Brunelle AN, Berkman CE. Probing for a hydrophobic a binding register in prostate-specific membrane antigen with phenylalkylphosphonamidates. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:4969–4979. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliver AJ, Wiest O, Helquist P, Miller MJ, Tenniswood M. Conformational and SAR analysis of NAALADase and PSMA inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem. 2003;11:4455–4461. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(03)00427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsukamoto T, Flanary JM, Rojas C, Slusher BS, Valiaeva N, Coward JK. Phosphonate and phosphinate analogues of N-acylated gamma-glutamylglutamate. Potent inhibitors of glutamate carboxypeptidase II. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002;12:2189–2192. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00360-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozikowski AP, Nan F, Conti P, Zhang J, Ramadan E, Bzdega T, Wroblewska B, Neale JH, Pshenichkin S, Wroblewski JT. Design of remarkably simple, yet potent urea-based inhibitors of glutamate carboxypeptidase II (NAALADase) J Med Chem. 2001;44:298–301. doi: 10.1021/jm000406m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozikowski AP, Zhang J, Nan F, Petukhov PA, Grajkowska E, Wroblewski JT, Yamamoto T, Bzdega T, Wroblewska B, Neale JH. Synthesis of urea-based inhibitors as active site probes of glutamate carboxypeptidase II: efficacy as analgesic agents. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1729–1738. doi: 10.1021/jm0306226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamamoto T, Hirasawa S, Wroblewska B, Grajkowska E, Zhou J, Kozikowski A, Wroblewski J, Neale JH. Antinociceptive effects of N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) peptidase inhibitors ZJ-11, ZJ- 17, and ZJ-43 in the rat formalin test and in the rat neuropathic pain model. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:483–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamoto T, Saito O, Aoe T, Bartolozzi A, Sarva J, Zhou J, Kozikowski A, Wroblewska B, Bzdega T, Neale JH. Local administration of N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) peptidase inhibitors is analgesic in peripheral pain in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:147–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhong C, Zhao X, Sarva J, Kozikowski A, Neale JH, Lyeth BG. NAAG peptidase inhibitor reduces acute neuronal degeneration and astrocyte damage following lateral fluid percussion TBI in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:266–276. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhong C, Zhao X, Van KC, Bzdega T, Smyth A, Zhou J, Kozikowski AP, Jiang J, O’Connor WT, Berman RF, Neale JH, Lyeth BG. NAAG peptidase inhibitor increases dialysate NAAG and reduces glutamate, aspartate and GABA levels in the dorsal hippocampus following fluid percussion injury in the rat. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1015–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foss CA, Mease RC, Fan H, Wang Y, Ravert HT, Dannals RF, Olszewski RT, Heston WD, Kozikowski AP, Pomper MG. Radiolabeled small-molecule ligands for prostate-specific membrane antigen: in vivo imaging in experimental models of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4022–4028. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guilarte TR, McGlothan JL, Foss CA, Zhou J, Heston WD, Kozikowski AP, Pomper MG. Glutamate carboxypeptidase II levels in rodent brain using [125I]DCIT quantitative autoradiography. Neurosci Lett. 2005;387:141–144. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guilarte TR, Hammoud DA, McGlothan JL, Caffo BS, Foss CA, Kozikowski AP, Pomper MG. Dysregulation of glutamate carboxypeptidase II in psychiatric disease. Schizophr Res. 2008;99:324–332. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mesters JR, Barinka C, Li W, Tsukamoto T, Majer P, Slusher BS, Konvalinka J, Hilgenfeld R. Structure of glutamate carboxypeptidase II, a drug target in neuronal damage and prostate cancer. EMBO J. 2006;25:1375–1384. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barinka C, Rinnova M, Sacha P, Rojas C, Majer P, Slusher BS, Konvalinka J. Substrate specificity, inhibition and enzymological analysis of recombinant human glutamate carboxypeptidase II. J Neurochem. 2002;80:477–487. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barinka C, Hlouchova K, Rovenska M, Majer P, Dauter M, Hin N, Ko YS, Tsukamoto T, Slusher BS, Konvalinka J, Lubkowski J. Structural basis of interactions between human glutamate carboxypeptidase II and its substrate analogs. J Mol Biol. 2008;376:1438–1450. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barinka C, Starkova J, Konvalinka J, Lubkowski J. A highresolution structure of ligand-free human glutamate carboxypeptidase II. Acta Crystallogr, Sect F: Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2007;63:150–153. doi: 10.1107/S174430910700379X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y, Foss CA, Mease RC, Nimmagadda S, Fox JJ, Kozikowski AP, Pomper MP. Synthesis, biodistribution, and experimental prostate tumor imaging of p-[125I]iodobenzoyl-lys- NH(CO)NH-glu. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:19P. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mease RC, Dusich CL, Foss CA, Ravert HT, Dannals RF, Seidel J, Prideaux A, Fox JJ, Sgouros G, Kozikowski AP, Pomper MG. N-[N-[(S)-1,3-Dicarboxypropyl]Carbamoyl]-4- [18F]Fluorobenzyl-L-Cysteine, [18F]DCFBC: A New Imaging Probe for Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3036–3043. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pomper MG, Musachio JL, Zhang J, Scheffel U, Zhou Y, Hilton J, Maini A, Dannals RF, Wong DF, Kozikowski AP. 11C-MCG: synthesis, uptake selectivity, and primate PET of a probe for glutamate carboxypeptidase II (NAALADase) Mol Imaging. 2002;1:96–101. doi: 10.1162/15353500200202109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hlouchova K, Barinka C, Klusak V, Sacha P, Mlcochova P, Majer P, Rulisek L. Biochemical characterization of human glutamate carboxypeptidase III. J Neurochem. 2007;101:682–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.More SS, Vince R. A metabolically stable tight-binding transitionstate inhibitor of glyoxalase-I. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:6039–6042. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.08.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mhaka A, Gady AM, Rosen DM, Lo KM, Gillies SD, Denmeade SR. Use of methotrexate-based peptide substrates to characterize the substrate specificity of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:551–558. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.6.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mlcochova P, Plechanovova A, Barinka C, Mahadevan D, Saldanha JW, Rulisek L, Konvalinka J. Mapping of the active site of glutamate carboxypeptidase II by site-directed mutagenesis. FEBS J. 2007;274:4731–4741. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. In: Carter CW Jr, Sweet RM, editors. Methods in Enzymology. 276. Academic Press; New York: 1997. pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Lebedev A, Wilson KS, Dodson EJ. Efficient anisotropic refinement of macromolecular structures using FFT. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:247–255. doi: 10.1107/S090744499801405X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McRee DE. XtalView/Xfit--A versatile program for manipulating atomic coordinates and electron density. J Struct Biol. 1999;125:156–165. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laskowski RA, McArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.