Abstract

Results from the DANISH Study (Danish Study to Assess the Efficacy of ICDs in Patients with Non-ischemic Systolic Heat Failure on Mortality) suggest that, for many patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) do not increase longevity. Accurate identification of patients who are more likely to die of an arrhythmia and less likely to die from other causes is required to ensure improvement in outcomes and wise use of resources. Until now, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) has been used as a key criterion for selecting patients with DCM for an ICD for primary prevention purposes. However, registry data suggest that many patients with DCM and an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest do not have a markedly reduced LVEF. Additionally, many patients with reduced LVEF die from non-sudden causes of death. Methods to predict a higher or lower risk of sudden death include the detection of myocardial fibrosis (a substrate for ventricular arrhythmia), microvolt T-wave alternans (MTWA; a marker of electrophysiological vulnerability) and genetic testing. Mid-wall fibrosis is identified by late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in around 30% of patients and provides incremental value in addition to LVEF for the prediction of SCD events. MTWA represents another promising predictor, supported by large meta-analyses that have highlighted the negative predictive value of this test. However, neither of these strategies have been routinely adopted for risk stratification in clinical practice. More convincing data from randomized trials are required to inform the management of patients with these features. Understanding of the genetics of DCM and how specific mutations affect arrhythmic risk is also rapidly increasing. The finding of a mutation in LMNA, the cause of around 6% of idiopathic DCM, commonly underpins more aggressive management due to the malignant nature of the associated phenotype. With the expansion of genetic sequencing, the identification of further high-risk mutations appears likely, leading to better informed clinical decision-making as well as providing insight into disease mechanisms. Over the next 5–10 years we expect these techniques to be integrated into the existing algorithm to form a more sensitive, specific and cost-effective approach to the selection of DCM patients for ICD implantation.

Keywords: Dilated cardiomyopathy, Sudden cardiac death, Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

Background

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a disease of the myocardium characterised by a reduction in left ventricular systolic function and left ventricular dilatation that cannot exclusively be explained by abnormal loading or ischemic injury.1 It is one of the most common cardiomyopathies, with a predicted incidence of 1 in 400 in the US.2 Three-year treated mortality rates remain high at 12–20%, with death typically resulting from heart failure (HF) or ventricular arrhythmia manifesting as sudden cardiac death (SCD).3–7 DCM accounts for a substantial proportion of SCD, especially amongst people of working age, with an annual incidence of 2–3%.6, 8–10 SCD is unheralded in 40–50% of cases and occurs out-of-hospital in the majority of patients.10, 11 Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) have the ability to promptly recognize and treat ventricular arrhythmias and thus form the cornerstone of SCD prevention. Patients with DCM compared with those with ischemic heart disease (IHD), are typically younger with less co-morbidity and therefore have a lower mortality risk from other causes. They, therefore appear ideal candidates to benefit from ICD therapy.

Current guidelines recommend the use of ICDs for the primary prevention of SCD in patients with DCM, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II–III HF and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <35%.12, 13 However, 4 individual randomized trials have failed to show a significant reduction in all-cause mortality with ICD therapy in patients with DCM and a LVEF <35% and only one trial has demonstrated mortality benefit in patients with both ischemic and non-ischemic aetiologies.5–7 A more precise risk stratification algorithm is therefore a major unmet need. In this review, we summarize the current evidence for primary prevention ICD implantation in patients with DCM and illustrate the need for improved risk stratification.5–7, 14 We discuss strategies and techniques that we expect to be used to improve risk stratification over the next 5–10 years by providing more comprehensive disease phenotyping. We review techniques that may improve risk stratification, building from simple clinical variables to more complex imaging techniques and genetic analysis.

Primary Prevention ICD Trials in DCM – The Need to Improve the Sensitivity and Specificity of the Current Approach

Five trials have investigated the effect of ICD implantation in patients with DCM without a history of cardiac arrest or hemodynamically unstable ventricular arrhythmia (Table 1).3–7 The Cardiomyopathy Trial (CAT) and the Amiodarone vs Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator (AMIOVIRT) trial were terminated prematurely due to a low mortality rate and lack of statistical power.3, 4 The Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) investigated the effect of primary prevention ICD implantation in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy or DCM with NYHA class II–III HF and an LVEF <35%.5 ICD therapy was associated with a reduction in overall mortality across both etiologies (HR 0.77; 97.5% CI: 0.62–0.96; p=0.007).

Table 1.

Randomised trials investigating the benefit of ICD implantation for the primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy.

| Study | N | Inclusion criteria | Intervention | Follow-up (median) | All-cause mortality | SCD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAT3 | 104 | LVEF<30% NYHA 2–3 |

ICD vs OMT | 23 months | Terminated early | |

| AMIOVIRT4 | 103 | LVEF≤35% NYHA 1–3 NSVT |

ICD vs amio | 24 months | Terminated early | |

| SCDHeFT (DCM cohort)5 | 1211 | LVEF<35% NYHA 2–3 |

ICD vs OMT vs amio | 46 months | I: 21.4%, C: 27.9% (5 yrs) HR 0.73; 95% CI 0.50–1.07 p=0.06 |

|

| DEFINITE6 | 458 | LVEF<36% NYHA 1–3 NSVT or PVCs |

ICD vs OMT | 29 months | I: 12.2%, C: 17.4% HR 0.65; 95% CI 0.40–1.06 p=0.08 |

I: 1.3%, C:6.1% HR 0.20; 95% CI 0.06–0.71 P=0.006 |

| DANISH7 | 1116 | LVEF<35% NYHA 2–3 (4 if CRT) NT-pro-BNP>200pg/ml |

ICD vs OMT | 68 months | I: 21.6%, C: 23.4% HR 0.87; 95% CI 0.68–1.12 p=0.28 |

I: 4.3%, C: 8.2% HR 0.50; 95% CI 0.31–0.82 p=0.005 |

(amio: amiodarone, C: optimal medical therapy arm, CI confidence interval, CRT – cardiac resynchronisation therapy, HR – hazard ratio, I: implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy arm, ICD – implantable cardioverter defibrillator, LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction, NYHA – New York Heart Association, NT-pro-BNP – N-terminal-pro-peptide brain natriuretic peptide, NSVT – non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, PVCs – premature ventricular complexes, OMT – optimal medical therapy; SCD – sudden cardiac death)

The Defibrillators in Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation (DEFINITE) study evaluated the effects of ICD therapy in patients with DCM, HF, a LVEF ≤35% and non-sustained VT or frequent ventricular ectopy.6 All-cause mortality was not significantly reduced with ICD therapy (HR 0.65; 95%CI 0.40–1.1; p=0.08) but a reduction in SCD was observed (HR 0.20; 95%CI 0.06–0.71; p=0.006). Current guidelines on the use of ICDs for the primary prevention of SCD in DCM are based on a meta-analysis of these trials, which demonstrated a reduction in all-cause mortality with ICD therapy (HR 0.74, p=0.02).12, 14, 15

Subsequently, the Danish Study to Assess the Efficacy of ICDs in Patients with Non-Ischemic Systolic Heat Failure on Mortality (DANISH) investigated ICD therapy versus optimal medical therapy (OMT) in patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy (76% idiopathic, 4% valvular, 11% hypertensive, 9% other), HF, LVEF <35% and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-pro-BNP) >200pg/ml.7 All-cause mortality was not lower in patients with ICDs (HR 0.87; 95% CI: 0.68–1.12; p=0.28); however SCD was reduced (HR 0.50; 95% CI: 0.31–0.82; p=0.005). Overall mortality was less than 5% per year and in the control group, only 1/3 of the deaths were attributed to SCD. Notably, the percentage of patients treated with contemporary OMT was higher than previous trials; 97% were prescribed angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers and 92% beta-blockers. In addition, 58% of patients in both arms received CRT, including 93% of those with LBBB and a QRS >150ms. CRT alone may reduce SCD risk by improving left ventricular function and preventing bradycardia-triggered lethal arrhythmias. An updated meta-analysis, including data from DANISH, has demonstrated a 23% reduction in all-cause mortality with ICD therapy compared with OMT alone (HR 0.77; 95% CI 0.64–0.91).16

Additional interpretation of the trials demonstrates the poor specificity of LVEF-based guidelines. In each of the trials, there was a low incidence of appropriate ICD therapies: 5.1% over 1 year in SCD-HeFT, 17.9% over 3 years in DEFINITE and 11.5% over 5.6 years in DANISH.5–7 This finding is partially explained by an improved prognosis for many with OMT. Left ventricular reverse remodelling occurs in up to 37% of patients treated with OMT, supporting the importance of postponing risk stratification until after a period of OMT.17 In DEFINITE, of those with a follow-up LVEF, approximately half had an improvement in LVEF >5% associated with substantially reduced mortality.18 Another explanation for the low incidence of appropriate therapies is a high residual incidence of death from competing causes; as the risk of non-sudden death increases, the chances of gaining benefit from ICD therapy diminishes.

Conversely, it is clear that the sensitivity of LVEF for predicting SCD is poor. Registries of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests have demonstrated that the majority of such patients do not have severely reduced LVEF.10, 11 In the Oregon and Maastricht registries, in those cases with pre-mortem echocardiography, only 20–30% had a low enough LVEF to meet criteria for an ICD.10, 11 DCM-specific registries have confirmed that, although the overall risk of SCD may be higher in patients with severely reduced LVEF, the number with mild or moderate reductions in LVEF is greater and their risk remains significant.19 Moreover, this group of patients are likely to have lower risks of death from competing causes and less likely to be limited by symptoms. The number of quality-adjusted life years gained from successful ICD therapy may therefore be greater.

The risk of complications and the costs of ICD implantation are also important considerations. Although less common compared with 10 years ago, the incidence of inappropriate shocks is associated with morbidity and reduced quality of life.6, 7, 20 Early procedure-related complications occur in 4% of cases, while device-related infection complicates 4.9%.7, 21 As well as worsening outcomes, complications add costs to the considerable expenditure associated with ICDs. It has been estimated that if devices were implanted as recommended, an extra 850,000 patients in the US would be offered ICD implantation, in addition to the 80,000 patients who currently receive them annually, at a total cost of $30 billion.22 These issues highlight the wider importance of optimizing the selection of patients.

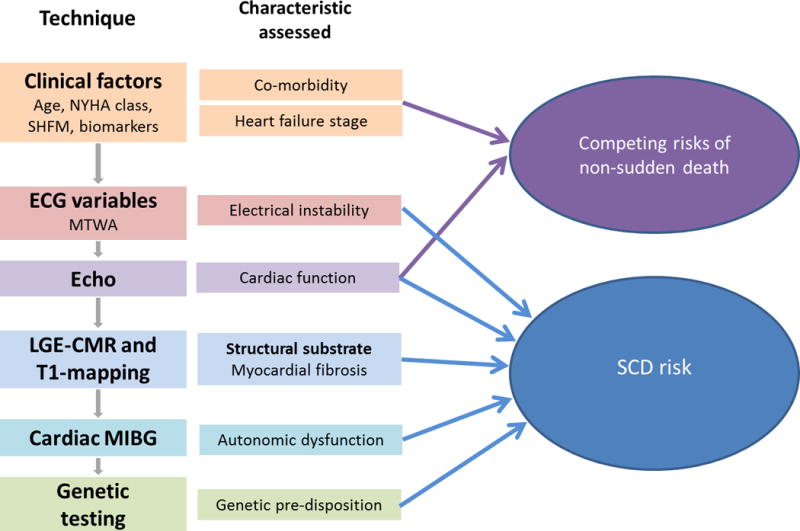

In conclusion, current research demonstrates the inadequacy of a risk stratification algorithm based on LVEF and illustrates the importance of developing a more sensitive, specific and cost-effective approach. We discuss other clinical and biomarker variables that may have a role in predicting the risk of non-sudden death and in the identification of those unlikely to benefit from ICD implantation and imaging and genetic techniques that detect those at high-risk of SCD (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the potential techniques that may be used to improve risk stratification. This is accompanied by the main characteristic of the condition assessed by each technique and the interaction of these characteristics with either the risk of sudden cardiac death or non-sudden death. (ECG – electrocardiogram; LGE-CMR – late gadolinium enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance; MIBG – metaiodobenzylguanidine; MTWA – microvolt T wave alternans; NYHA – New York Heart Association; SCD – sudden cardiac death; SHFM – Seattle Heart Failure Model)

Stage of Disease, Co-morbidities and Competing Risks from Non-Sudden Causes of Death

It has long been recognized that patients with advanced HF are unlikely to benefit from ICD therapy due to high rates of death from non-arrhythmic causes. This is reflected in guidelines that do not recommend ICD implantation for patients with NYHA Class IV symptoms, unless cardiac transplant is planned, or for those with a life expectancy < 1 year.12, 13 The risk of death from non-sudden causes is especially relevant in older patients and in those with more co-morbidities. In planned sub-group analysis of the DANISH trial, patients aged >68 years of age had a trend towards increased mortality with ICD implantation (HR 1.19; 95% CI 0.81–1.73; p=0.38), in contrast to patients <59 years of age who had a lower mortality with an ICD (HR 0.51; 95% CI 0.29–0.92; p=0.02).7 Additionally, a meta-analysis of trials of primary prevention ICDs in ischemic and non-ischemic HF demonstrated the absence of survival benefit in patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of <60 ml/minute/1.73mm.23 This highlights the role that age and measures of kidney function may have in identifying patients who are unlikely to gain benefit from ICD implantation.

Risk scores such as the Seattle Heart Failure Model have been developed to predict prognosis in patients with HF, incorporating variables such as NYHA class and prescription of medical therapies with age and kidney function.24 The Seattle model has been shown to be more accurate in the stratification of the risk of non-sudden death compared with SCD in populations with ischemic and non-ischemic HF.25 For example, patients with a score of 3 and 4, compared with those with a score of 0, have a relative risk of HF death of 38.4 and 87.6, and a relative risk of SCD of only 6.5 and 6.5, respectively. This highlights that although the risk of SCD rises with worsening HF, the rise in the risk of HF death is even greater, reducing chances of gaining quality-adjusted life years from ICD therapy. While similar models have been developed for the prediction of SCD in HF populations and the wider general population, these are limited by an inability to reliably discriminate between the risk of SCD and non-sudden death and therefore have limited clinical utility.26–28

There is growing interest in the use of circulating biomarkers of myocardial stress and fibrosis such as natriuretic peptides, troponin, galectin-3 and soluble ST2 to predict prognosis. However, these biomarkers generally reflect the severity of cardiac dysfunction rather the specific risk of SCD. They may be used to identify patients who are unlikely to benefit from ICD therapy due to a high-risk of death due to progression of HF. In pre-specified sub-group analysis of DANISH, patients with a NT-pro-BNP>1177pg/ml randomized to ICD therapy had similar all-cause mortality to those in the control arm (HR 0.99; 95% CI: 0.73–1.36; p=0.96), while mortality was lower in those assigned to an ICD when NT-pro-BNP was <1177pg/ml (HR 0.59; 95% CI: 0.38–0.91; p=0.02).7 Similarly, Ahmad and colleagues demonstrated a stronger association between NT-pro-BNP, galectin-3 and soluble ST2 and HF death compared with SCD in patients with ischemic and non-ischemic HF.29 In summary, biomarkers, in combination with clinical variables and prognostic scores, offer the most potential for the identification of patients with an excessively high-risk of death from competing causes, who are thus unlikely to benefit from ICD therapy. The threshold at which the risk of death from competing causes outweighs the risk of SCD and the benefit from ICD therapy becomes unlikely is not clear.

Markers of Electrical Instability and SCD Risk

Many studies have evaluated the ability of electrical measurements to predict the risk of SCD in DCM30. These have included 1) electrocardiogram (ECG) findings such as QRS duration, QRS fragmentation, microvolt T wave alternans (MTWA), left bundle branch block and late potentials on signal averaging; 2) markers of autonomic tone including baroreflex sensitivity, heart rate variability, heart rate turbulence; and 3) ventricular ectopy and non-sustained VT on monitoring or following programmed stimulation. The results of these, often small studies have been inconsistent and their combined utility is limited by the use of different end-points.30

A large meta-analysis combined 45 studies, including 6,088 patients with non-ischemic DCM, in an attempt to summarize existing data.30 When available, arrhythmic end-points including SCD, ventricular arrhythmia or appropriate ICD discharge were used; all-cause mortality was used as an alternative when these were not available. Although inter-study reproducibility was poor for the majority of variables, the authors concluded that the most promising for the prediction of adverse events were QRS complex fragmentation (OR 6.73; 95% CI 3.85–11.76; p<0.001) and the presence of MTWA (OR 4.66; 95% CI 2.55–8.53; p<0.001). The odds ratios for the majority of the remaining parameters were between 1.5 and 3.0, suggesting lower predictive value (Table 2).

Table 2.

Electrophysiological parameters and their ability to predict adverse arrhythmic events

| Category | Parameter | Studies | Events n (%) | Odds ratios (95% CI) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomic | Baroreflex sensitivity | 2 | 48/359 (13.4) | 1.98 (0.60–6.59) | 16.3 | 89.9 | 0.23 |

| Heart rate turbulence | 3 | 66/434 (15.2) | 2.57 (0.64–10.36) | 22.1 | 88.1 | 0.16 | |

| Heart rate variability | 4 | 83/630 (13.2) | 1.72 (0.80–3.73) | 16.9 | 89.7 | 0.13 | |

| Surface electrical | QRS duration & LBBB | 10 | 262/1797 (14.6) | 1.51 (1.13–2.01) | 18.5 | 87.6 | 0.01 |

| Fragmented QRS | 2 | 65/652 (10.0) | 6.73 (3.85–11.76) | 24.0 | 94.8 | <0.001 | |

| Positive SAECG | 10 | 152/1119 (13.6) | 2.11 (1.18–3.78) | 18.9 | 89.5 | 0.017 | |

| T-wave alternans | 12 | 177/1631 (10.9) | 4.66 (2.55–8.53) | 14.8 | 97.0 | <0.001 | |

| QRS-T angle | 1 | 97/455 (21.3) | 2.01 (1.22–3.31) | 25.4 | 85.5 | 0.006 | |

| Arrhythmia | Positive EPS | 15 | 146/936 (15.6) | 2.49 (1.40–4.40) | 29.2 | 86.9 | 0.004 |

| Non-sustained VT | 18 | 403/2746 (14.7) | 2.92 (2.17–3.93) | 20.7 | 90.3 | <0.001 |

Figure adapted from30 (ECG – electrocardiogram, EPS – electrophysiological study, LBBB – left bundle branch block, NPV – negative predictive value, PPV positive predictive value, VT – ventricular tachycardia).

While the small number of studies limits the ability to interpret the predictive ability of QRS fragmentation, a large number of studies support the potential of MTWA and a meta-analysis of patients with non-ischemic DCM has corroborated the findings of Goldberger and colleagues.31 A study in a mixed ischemic and non-ischemic population has suggested that the presence of MTWA may be a stronger predictor of arrhythmia when present in patients taking beta-blockers (patients on beta-blockers: HR 5.39; 95% CI 2.68–10.84 p<0.001; entire population: HR 1.95; 95% CI 1.29–2.96; p=0.002).32 Others have emphasized the negative predictive value of a negative MTWA test33; however, it should be noted that even a coin toss has a high negative predictive value when the event rate is low.34 Authors have proposed the use of MTWA testing to select patients with a LVEF <35% who are unlikely to benefit from ICD implantation, but this has not been validated.35

Echocardiography

Echocardiography is the first-line imaging investigation in the work-up of patients with DCM. Use of echocardiography measurements to predict arrhythmic events is therefore an attractive concept. The ability of global longitudinal strain and mechanical dispersion, a measure of mechanical dyssynchrony, to predict sustained ventricular arrhythmia or SCD was investigated in 94 patients with non-ischemic DCM over 22-months by Haugaa and colleagues.36 They found that both measures independently predicted the major arrhythmic end-point (per 1% increase in strain – HR 1.26, 95% CI 1.03–1.54, p=0.02; per 10ms increase in mechanical dispersion – HR 1.20, 95% CI 1.03–1.40; p=0.02). They also demonstrated that both variables had larger areas under the curve on receiver operator curve analyses for the prediction of the primary outcome compared with LVEF (area under the curve – strain: 0.82; mechanical dispersion: 0.80; LVEF: 0.72). Another study investigated 124 patients with non-ischemic DCM prior to primary prevention ICD implantation.37 Longitudinal strain was independently associated with the primary end-point of appropriate ICD therapy, albeit to a modest degree (per % increase – HR 1.12; 95% CI 1.01–1.20; p=0.032). Importantly, however it appears unlikely that functional techniques, such as strain measurement, will provide adequate discrimination between the risk of SCD and death from HF.

The Role of Myocardial Fibrosis in SCD Risk Stratification

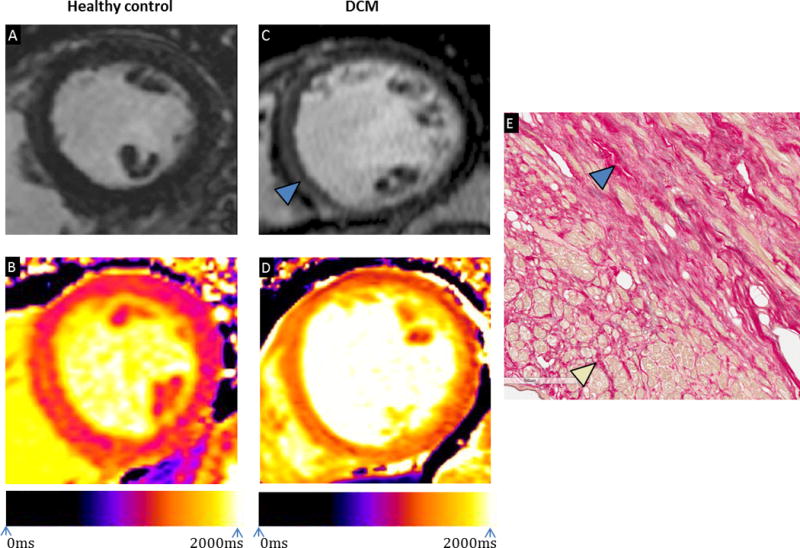

One of the characteristic pathological features of DCM is the formation of myocardial fibrosis, a consequence of an increase in collagen formation in the extracellular matrix and myocyte cell death.38 Histological studies have demonstrated 2 forms of fibrosis, replacement and interstitial fibrosis.38 Replacement fibrosis describes discrete areas of myocardial scarring that develop as a result of myocyte cell death while interstitial fibrosis is the result of expansion of the interstitium with accumulation of collagen in the absence of cell death (Figure 2).22 Fibrosis is the result of activation of the renin-angiotension-aldosterone system and the beta-adrenergic axis, which occur as part of the HF syndrome.39 Other environmental insults, implicated in the etiology of DCM, such as chemotherapy and viral myocarditis, play a role through the activation of inflammatory networks and production of reactive oxygen species.39 The end result is the activation of myofibroblasts, the production of collagen and myocyte cell death.38, 39

Figure 2.

(A) Late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance image of a mid-ventricular short-axis slice in a healthy control; (B) Native T1 map of a mid-ventricular short-axis slice in a healthy control with a mean myocardial T1 of 1240ms; (C) Late gadolinium enhancement image of a mid-ventricular short axis slice in a patient with dilated cardiomyopathy demonstrating linear mid-wall enhancement; (D) Native T1 map of a mid-ventricular short-axis slice in a patient with dilated cardiomyopathy with a mean myocardial T1 of 1375ms; Scans performed on Siemens Skyra 3T (Erlangen, Germany); (E) Microscopic examination of a sample taken from the septum of an explanted heart post-transplant demonstrating the presence of replacement fibrosis (blue arrow) and peri-cellular interstitial fibrosis (yellow arrow).

(DCM – dilated cardiomyopathy)

Fibrosis is thought to provide a substrate for ventricular arrhythmia. An electrical mapping study in patients with DCM demonstrated that only those with replacement fibrosis, identified by late gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (LGE-CMR), had inducible VT or a history of sustained VT.40 Moreover, in patients with inducible VT, the major component was mapped to the area of replacement fibrosis. Mapping studies have also linked the presence of fibrosis with fractionated electrograms, slowed conduction and conduction block that have been associated with VT and VF.41, 42 The gray-zone between areas of fibrosis and surviving myocardium is thought to act as the nidus for re-entry wavefronts in patients with IHD and similar mechanisms may account for 80% of VT in DCM.43

Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, Replacement Mid-wall Fibrosis and Outcome Prediction

LGE-CMR imaging has demonstrated that replacement fibrosis occurs in around 30% of patients with DCM. This frequently occurs in a linear mid-wall distribution and has been validated with histology (Figure 2).44, 45 Multiple studies have demonstrated an association between mid-wall fibrosis (MWF) on LGE-CMR imaging and SCD events in patients with DCM (Table 3).44–52

Table 3.

Studies investigating the impact of mid-wall fibrosis on major arrhythmic outcomes in DCM.

| Authors | N (MWF) | Inclusion criteria | Arrhythmic end-point | Follow-up (median) | Occurrence of end-point as per presence of MWF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gulati et al (2013)44 | 472 (142) | Consecutive patients referred for CMR | SCD* and aborted SCD† (excluding ATP) | 64 | Total events 65 Event rate: MWF: 29.6%; no MWF 7.0% HR 5.24 (95% CI 3.15–8.72; p<0.001) |

| Assomull et al (2006)45 | 101 (35) | Consecutive patients referred for CMR | SCD* and sustained VT | 22 | Total events: 7 Event rate: MWF: 14.3%; no MWF 3.3% HR 5.2 (95% CI 1.0–26.9; p=0.03) |

| Neilan et al (2013)46 | 162 (81) | Consecutive patients referred for CMR | SCD* and aborted SCD† (including ATP) | 29 | Total events: 37 Event rate: MWF: 41.9%; no MWF 3.7% HR 14.0 (95%CI 4.39:45.65; p<0.0001) |

| Masci et al (2014)49 | 228 (61) | Patients with DCM without a history of HF | Aborted SCD† (including ATP) | 23 | Total events: 8 Event rate: MWF: 9.8%; no MWF 1.2% HR 8.31 (95%CI 1.66:41.55; p=0.01) |

| Perazzolo-Marra et al (2014)50 | 137 (76) | Consecutive patients | SCD* and aborted SCD† (including ATP) | 36 | Total events: 22 Event rate: MWF: 22.3%; no MWF 8.2% HR 4.17 (95% CI 1.56–11.2; p=0.005) |

| Leyva et al (2012)51 | 97 (25) | Patients referred for CRT | SCD* | 35 | Total events: 3 Event rate: MWF: 15.0%; no MWF 0% HR 31.0 (95% CI 1.5–627.8; p=0.013) |

witnessed cardiac arrest, death within 1 hour after onset of symptoms or unexpected, unwitnessed death in a patient known to have been well 24 hours previously;

sustained VT, resuscitated cardiac arrest, appropriate ICD intervention; ATP – antitachycardia pacing, CI - confidence interval, DCM – dilated cardiomyopathy, HF- heart failure, HR – hazard ratio, PVCs – premature ventricular complexes, OMT – optimal medical therapy; SCD – sudden cardiac death, VT –ventricular tachycardia

The largest study followed 472 patients with non-ischemic DCM of all severities for a median of 5.3 years44. Similar to other studies, 30.0% of patients had MWF.47, 48 Overall, 29.6% of patients with MWF reached the arrhythmia composite of SCD or aborted SCD (defined as an appropriate ICD shock or a non-fatal episode of VF or spontaneous VT causing hemodynamic compromise and requiring cardioversion), compared with 7.0% of those without (HR 5.24; 95% CI 3.15–8.72; p<0.001). Additionally, 26.8% of patients with MWF died compared with 10.6% of patients without (HR 2.96; 95% CI 1.87–4.69; p<0.01). After adjustment for other prognostic factors, the presence and extent of MWF predicted the arrhythmia composite (presence of MWF – HR 4.61; 95% CI 2.75–7.74; p<0.001; per 1% increase – HR 1.15; 9% CI 1.10–1.20;p<0.001) and all-cause mortality (presence of MWF – HR 2.43; 95% CI 1.50–3.92; p<0.001; per 1% increase in extent – HR 1.11; 9% CI 1.06–1.16;p<0.001). There was also an association between the presence of MWF and HF events (HR 1.62; 95% CI 1.00–2.61; p=0.049), although this was notably weaker than that with SCD events. The addition of MWF to LVEF significantly improved risk re-classification for SCD/aborted SCD, with 29% of patients being correctly re-classified after the addition of MWF to a model including LVEF.

Another study followed 162 non-ischemic DCM patients who underwent LGE-CMR imaging prior to planned ICD implantation for a median of 29 months.46 This selected cohort had a higher incidence of MWF, occurring in 50.0%. Following adjustment, the presence and extent of MWF were the strongest predictors of the primary end-point, which was a composite of cardiovascular death and ventricular arrhythmia terminated by ATP or ICD shock (presence of MWF: HR 6.21; 95% CI 1.73–22.2; p<0.0004; per % increase – HR 1.16; 95% CI 1.07–1.21; p<0.0001). The presence and extent of MWF also predicted the secondary arrhythmic outcome including ICD intervention (appropriate shock and ATP) and SCD (presence of MWF: HR 14.0; 95% CI 4.39–45.65; p<0.0001; per % increase – HR 1.17; 95%CI 1.12–1.22; p<0.0001). The study demonstrated that LGE quantification using the full-width at half maximum method and the >2 standard deviation approach was prognostic. LGE occupying >6.1% of the myocardium by the >2 standard deviation method or >4.4% by the full width at half maximum method provided the highest sensitivity and specificity for predicting the primary end–point, with area under the curve values of 0.92 and 0.93, respectively. Data, however, are yet to be produced for the prediction of hard SCD events alone. Variability in methods of quantification highlights the need for a single standardized approach. Moreover, the subjectivity inherent in many techniques suggests that caution should be exercised in applying specific cut-off values. A binary approach based on the presence or absence of MWF is currently the most robust method, with MWF defined as an area of LGE clearly visible in two phase-encoding directions and two orthogonal planes, extending beyond the ventricular insertion sites.

Three large meta-analyses, including 1488, 1443, 2948 patients with non-ischemic DCM, confirmed the above findings.47, 48, 52 In the pooled analysis of Kuruvilla, et al., patients with MWF had significantly higher rates of SCD and aborted SCD (OR 5.32; 95% CI 3.45–8.20; p<0.00001) and greater all-cause mortality (OR 3.27; 95% CI 1.94–5.51; p<0.00001).47 Similarly, Diesetori and colleagues demonstrated that the presence of MWF predicted an arrhythmic composite end-point including SCD, successful resuscitation from VF, sustained VT and appropriate ICD therapy (ATP and appropriate shocks) (OR 6.27; 95% 4.15–9.47; p<0.000001).48 More recently, Di Marco, et al. reported an association between the presence of LGE and the composite end-point of sustained ventricular arrhythmia, appropriate ICD therapy and SCD (OR 4.3; 95% CI 3.3–5.8; p<0.001).52 Interestingly, this association was observed in studies with a mean LVEF >35% (OR 5.2; 95% CI 3.4–7.9; p<0.001) and those with a mean LVEF <35% (OR 4.2; 95% CI 2.4–7.2; p<0.001).

A recent study performed exclusively in patients with non-ischemic DCM and a LVEF >40% suggests that LGE-CMR imaging identifies patients with less severe left ventricular impairment at high-risk of SCD.53 Those with MWF had significantly higher rates of SCD and aborted SCD (defined as an appropriate ICD shock, a non-fatal episode of VF or VT causing hemodynamic compromise and requiring cardioversion) compared to those without (HR 9.2; 95% CI 3.9–21.8; p<0.0001) and this remained similar after adjusting for other prognostic variables (HR 9.3; 95% CI 3.9–22.3; p<0.0001). Importantly, the risk of death from competing causes in patients with MWF and mild or moderate reductions in LVEF was low. However, further studies are needed to establish whether patients with LVEF >35% and high-risk features benefit from ICD therapy.54

Although promising, there are currently no data from randomized studies confirming that patients with MWF benefit from ICD implantation, and it remains unclear whether the addition of LGE to LVEF will sufficiently improve risk stratification or whether additional variables will be required.55 Pending randomized studies, the presence or absence of MWF on LGE-CMR imaging may be used to aid decision-making with regards to ICD implantation in borderline cases. Further work is required to investigate the linearity of the relationship between the extent of MWF and SCD events and whether there are reproducible amounts of MWF that reliably predict hard adverse arrhythmic events with the most accuracy.

The Role of Interstitial Fibrosis and the Potential of T1-mapping

Interstitial fibrosis is an almost universal finding in DCM.38 Although less comprehensive than the work on replacement fibrosis, there is some evidence to suggest that interstitial fibrosis is involved in the maintenance of re-entry circuits and in the generation of focal tachycardias.56 Non-invasive measurement of interstitial fibrosis therefore offers potential for risk stratification.39 T1-mapping is a CMR technique that quantifies the T1 relaxation time of each myocardial voxel. A T1-map can be constructed where each voxel’s signal intensity corresponds to the T1 time (Figure 2). If performed before and after administering gadolinium, an extracellular contrast, the myocardial extracellular volume (ECV) can be calculated by estimating the amount of contrast in the extracellular compartment relative to the blood pool.57 Native (pre-contrast) T1 times and ECV fraction correlate with the degree of interstitial fibrosis in a range of diseases including DCM.57, 58 Aus dem Siepen and colleagues demonstrated good correlation between ECV and the collagen volume fraction on myocardial biopsy in patients with varying severities of non-ischemic DCM (r=0.85).58 Another study demonstrated strong correlation between ECV on pre-transplant CMR and collagen volume fraction on 96 post-transplant tissue samples taken from 16 segments of 6 patients’ explanted hearts (r=0.75).59 Additionally, the authors demonstrated significantly higher ECV values in myocardial segments free of LGE in patients pre-transplant compared to ECV values in healthy controls (41.4 +/−5.0% vs 25.5% +/−2.6%; p<0.001).59 This suggests that it may be possible to measure interstitial fibrosis non-invasively. Early work has investigated the predictive value of T1-mapping in risk prediction.60, 61

The largest study in 637 patients with non-ischemic DCM demonstrated a significant association between all-cause mortality and native T1 values (per 10ms - HR 1.10; 95% CI 1.05–1.13; p<0.001) and the extent of LGE (per % – HR 1.09; 95% CI 1.02–1.16; p=0.009).60 Chen and colleagues investigated 130 patients with both non-ischemic and ischemic HF referred for primary prevention ICD implantation.61 Elevated native T1-values (per 10ms – HR 1.10; 95% CI 1.04–1.16; p=0.001), the extent of MWF (per % – HR 1.10; 95% CI 1.04–1.15; p<0.001) and a secondary prevention indication (HR 1.70; 95% CI 1.01–1.91; p=0.048) predicted the composite of appropriate ICD therapy (shock or ATP) and sustained ventricular arrhythmia. ECV, however, did not predict the end-point (HR 1.01; 95% CI 0.94–1.11). These studies illustrate a potential role for T1-mapping in risk stratification. However, further studies are required to clarify whether one measure is superior to the other. The crucial question is whether T1-mapping provides additional value to LGE, which already forms part of a routine scan.

An alternative approach is the use of biomarkers of collagen turnover as a surrogate for myocardial fibrosis.62 Correlation between serum procollagen type I carboxy-terminal peptide (PICP) and fibrosis on myocardial biopsy has been reported in hypertensive patients and an association between galectin-3 and MWF on LGE-CMR in non-ischemic DCM patients has been demonstrated.63, 64 Current studies investigating collagen biomarkers are limited by small numbers of patients and outcome events and therefore no conclusions can be drawn about their potential role in SCD risk assessment.65 More research is required.

Cardiac MIBG imaging

Autonomic dysfunction has long been associated with ventricular arrhythmogenesis.66 Variable sympathetic activation of the myocardium results in heterogeneities in conduction velocities and refractory periods, creating a pro-arrhythmic environment.67 Although not part of routine practice, it is possible to detect cardiac autonomic dysfunction using 123-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy. Parameters indicating autonomic dysfunction include elevated tracer washout rates, abnormal ratio of uptake between the heart and mediastinum and large myocardial tracer defects.

Several studies have supported the ability of these parameters to predict SCD and adverse arrhythmic events in patients with DCM and broader HF populations (Table 4).68–73 Merlet and colleagues performed a study exclusively evaluating patients with non-ischemic DCM.68 In multivariable analysis, they found that radionuclide-determined LVEF (p=0.02) and low heart:mediastinum (H:M) ratio (p<0.0001) predicted all-cause mortality while low H:M ratio predicted SCD (p=0.0015). The AdreView Myocardial Imaging for Risk Evaluation in Heart Failure (ADMIRE-HF) study demonstrated that in patients with ischemic and non-ischemic HF, a H:M ratio ≥1.6 was associated with a lower risk of adverse arrhythmic events (defined as spontaneous sustained VT, resuscitated cardiac arrest or appropriate ICD therapy including ATP; 3.5% vs 10.4%; p<0.01) and a lower incidence of the primary composite end-point that included arrhythmic events, NYHA progression and cardiovascular death (HR 0.36; 95% CI 0.17–0.75; p=0.006).70 Survival modelling of patients without an ICD at enrollment demonstrated that H:M ratio added incremental prognostic value and improved net re-classification, however it did not identify those who had improved survival with ICD implantation.67, 74 A sub-study of ADMIRE-HF assessed the value of summed rest score on single photon emission computed tomography, a marker of myocardial scar, in risk stratifying 317 patients with non-ischemic HF.69 Overall, there were 22 arrhythmic events, defined as appropriate ICD therapy (ATP or shock), resuscitated cardiac arrest and sustained VT, over a median of 17 months. On univariable analysis, H:M ratio <1.6 and a summed rest score >8 were associated with the end-point. Multivariable analysis performed in patients with a H:M ratio<1.6 demonstrated that a summed rest score of >8 was the only independent predictor of the end-point.

Table 4.

Studies investigating the use of 123-metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy for the prediction of adverse arrhythmic events in patients with heart failure.

| Study | N (DCM) | Inclusion criteria | Follow-up (median) | End-point | Variable | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Merlet et al (1999)68 | 112 (112) | LVEF<40% NYHA 2–4 |

27 months | SCD* | H:M ratio (continuous variable) | Low H/M predicted SCD; p=0.0015 (HR/CIs not quoted) |

| Sood et al (2013)69 | 317 (317) | LVEF<35% NYHA 2–3 |

17 months | Arrhythmic event† | SRS>8 in pts with H:M<1.6 | HR 3.3 95% CI 1.1:9.8 P=0.032 |

| ADMIRE-HF (2010)70 | 961 (327) | LVEF<35% NYHA 2–3 |

17 months | Arrhythmic event† | H:M≥1.60 | HR 0.37 95% CI: 0.16:0.85 P=0.020 |

| Boogers et al (2010)71 | 116 (30) | Referred for ICD | 23 months | Appropriate ICD therapy‡ | Late defect score >26 | HR 12.81 95% CI: 3.01–54.50 P<0.01 |

| Tamaki et al (2009)72 | 106 (51) | LVEF<40% NYHA 1–3 |

65 months | SCD* | Abnormal WR | HR 4.79 95% CI 1.55–14.76 P=0.0064 |

| Kioka et al (2007)73 | 97 (46) | LVEF<40% NYHA 1–3 |

65 months | SCD* | Abnormal WR | HR 6.13 95% CI 1.53–24.5 P<0.05 |

witnessed cardiac arrest, death within 1 hour after onset of symptoms or unexpected, unwitnessed death in a patient known to have been well 24 hours previously;

sustained VT, resuscitated cardiac arrest, appropriate ICD shock or ATP;

appropriate ICD shock or ATP; CI confidence interval, H:M – heart:mediastinal ratio; HR – hazard ratio, ICD – implantable cardioverter defibrillator, LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction, NYHA – New York Heart Association, SCD – sudden cardiac death; WR – washout rate

These studies support the hypothesis linking autonomic dysfunction to increased rates of SCD. Further larger studies confirming the findings in patients with DCM and the measurements with the best sensitivity and specificity for the prediction of SCD are required.

Unravelling the Complex Genetic Frameworks of DCM and Sudden Death

The Genetic Basis of DCM

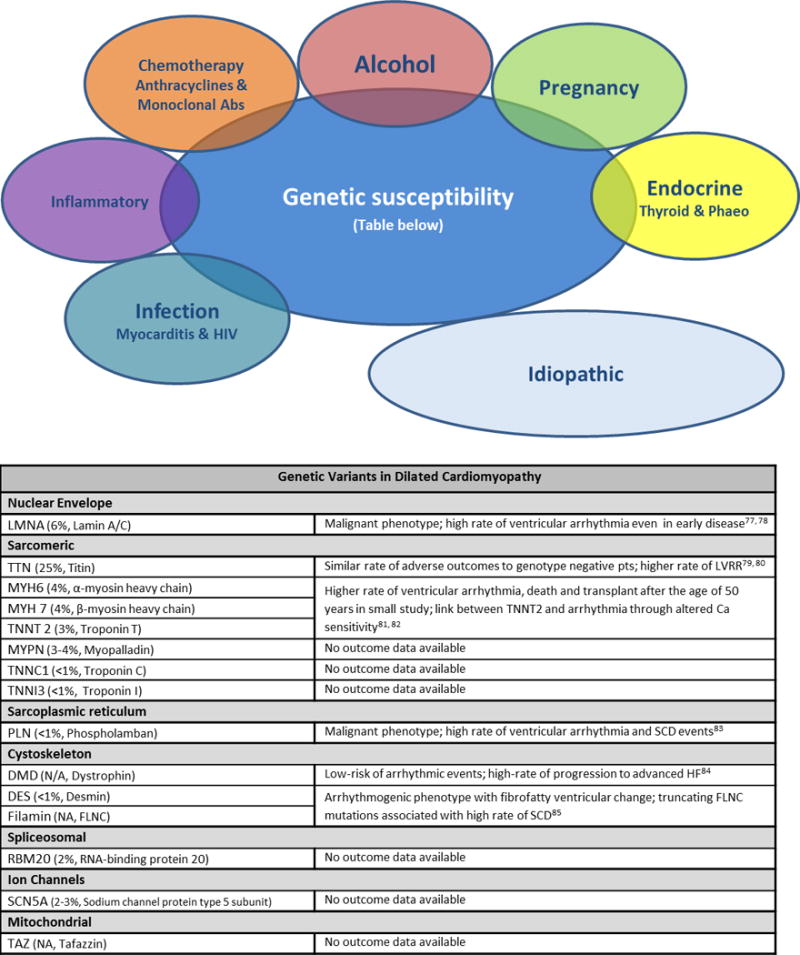

Over the last 20 years, as a result of advances in sequencing, literature on the genetics of DCM has increased exponentially. Familial DCM is defined as idiopathic DCM in at least 2 closely related relatives and is thought to account for 25–50% of idiopathic DCM.1 In familial DCM, a genetic cause is identified in 30–40% of cases with over 100 single genes linked to the disease (Figure 3).75, 76 The majority of mutations occur in autosomal genes, with a small number of X-linked and mitochondrial mutations identified. Most are unique to the family in which they were discovered and are termed ‘private mutations’.2 Inheritance has long been considered Mendelian and therefore thought secondary to a single potent genetic mutation, with segregation in affected family members, crossing generations. However, cases with reduced penetrance, variable expressivity and multiple mutations are not infrequent. Reduced and age-dependent penetrance and variable expressivity illustrate the importance of environmental modifiers, such as viral triggers or excess alcohol consumption, which may unmask the phenotype (Figure 3).2, 77–85 A study has demonstrated a similar incidence of genetic variants in women with peripartum cardiomyopathy compared to patients with idiopathic DCM, suggesting a shared genetic etiology across the spectrum of DCM, unmasked by different insults.86

Figure 3.

Figure demonstrating the acquired and genetic insults implicated in the aetiology of dilated cardiomyopathy followed by the common genetic mutations associated with DCM (incidence of mutations in cases of idiopathic DCM followed by the protein encoded by the gene2) and data on disease outcomes.

(Abs – antibodies; HIV – human immunodeficiency virus; phaeo – phaeochromocytoma)

The diverse range of genes thought to cause DCM, encoding for a wide range of proteins with different functions, not only adds to the challenges of variant interpretation but also creates them in the search for new mutations3. The most common mutations occur in genes encoding sarcomeric proteins and also in genes related to the nuclear envelope and the cytoskeleton. With the growth in sequencing, the identification of rare variants that contribute to the disease phenotype and carry adverse arrhythmic risk is becoming foreseeable. Considering that DCM is often diagnosed late and occasionally at post-mortem, genetic screening enabling early diagnosis and risk stratification is attractive. We discuss our understanding of the risk associated with specific mutations and work aimed at identifying genetic modifiers of risk.

DCM Genetics and SCD Risk

Despite advances, there are currently only specific instances when genetic results influence risk stratification. The most common circumstance is the identification of a pathogenic mutation in the LMNA gene, which encodes both the Lamin A and C proteins, part of the nuclear envelope. More than 200 LMNA mutations have been associated with the development of DCM with variable involvement of skeletal muscle.76 The cardiac phenotype is associated with premature conduction system disease and atrial and ventricular arrhythmia. The largest study on lamin cardiomyopathy to date followed 94 patients with LMNA mutations over a median of 57 months.77 Sixty patients had phenotypic evidence of disease at enrollment and all those who reached 60 years of age developed the phenotype. Mortality in patients with a positive phenotype was 40% at 5 years, while 45% suffered SCD or aborted SCD. This confirmed LMNA cardiomyopathy to be a malignant and penetrant condition with worse outcomes compared with other forms of DCM. This has been replicated in other studies and supports the view that ICDs should be implanted earlier than current guidelines recommend in these patients and in all those requiring pacemaker implantation.77, 78

Truncating mutations of the TTN gene, which encodes the giant titin protein, are thought to be the most common causative mutations, occurring in 25% cases of FDCM, 18% of sporadic cases and <1% of controls.87 Two molecules of titin span the length of the sarcomere and act to generate and regulate contractile force.88 Titin has an important role in modulating responses to insults and loads and truncating mutations appear to result in susceptibility to developing contractile impairment.89 Herman and colleagues studied 312 patients with DCM and demonstrated similar rates of adverse outcomes, in patients with truncating mutations in TTN compared to those without.79 More recently, Jansweijer, et al. demonstrated that DCM patients with truncating variants in TTN had a milder phenotype of disease at baseline and higher rates of reverse remodelling compared with patients with LMNA mutations and those without a variant identified.80 This suggests that DCM related to TTN may be a more treatable form. Larger studies investigating SCD end-points are required.

Studies in patients with other mutations have been smaller. Merlo and colleagues studied 179 families with DCM and compared patients with rare sarcomeric gene variants to genotype negative patients.81 Overall, 52 patients had rare variants in TTN, MYH6, MYH7, TNNT2 and MYBC and although these patients had a higher LVEF at baseline, after 50 years of age, rates of adverse outcomes including ventricular arrhythmia, death and cardiac transplantation were higher. Other studies have suggested that mutations in TNNT2, may predispose to ventricular arrhythmias independent of structural changes and this may be mediated through alterations in myocyte calcium sensitivity.82, 90 A study has demonstrated reduced arrhythmic susceptibility in mice with TNNT2 mutations treated with a calcium de-sensitizer.90

A founder mutation in the PLN gene, which encodes phospholamban, a protein with an important role in calcium homeostasis, has been associated with profound arrhythmic tendencies in patients with DCM and also those without structural phenotypes.83 Van Rijsingen and colleagues studied 403 carriers of a specific mutation in the PLN gene, 21% of whom met diagnostic criteria for DCM.83 Over 42 months, 19% had malignant ventricular arrhythmia defined as SCD, resuscitated cardiac arrest or appropriate ICD intervention. In patients with an LVEF <45%, the incidence of ventricular arrhythmia rose to 39%. These studies suggest that mutations in genes controlling calcium handling, also known to cause DCM, may influence arrhythmic risk independent of structural changes. This provides opportunity for the development of therapeutics targeting specific mechanisms of arrhythmogenesis.

Another study in 436 men with DCM identified dystrophin variants in 34.84 Over 60 months, patients with dystrophin mutations had high rates of HF events with 23% undergoing transplantation and 26% dying from HF. Conversely, however, they demonstrated low incidences of major arrhythmic events with no patients suffering SCD or life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia. Although small, this study suggests that patients with dystrophin variants should be streamlined to advanced HF therapies rather than ICD implantation.

Recently, truncating mutations in FLNC, a gene which encodes filamin, a protein that attaches membrane proteins to the cystokeleton, have been associated with an arrhythmogenic phenotype, similar to that observed with desmin mutations.85 In 2,877 patients with inherited cardiovascular disease, truncating mutations in FLNC were identified in 28 probands and 54 relatives.85 Overall, 97% of carriers over the age of 40 years had phenotypic evidence of the disease characterised by LV dilatation, reduced LVEF and myocardial fibrosis. Twelve carriers suffered SCD during the study, conducted over 3.5 years, and there was a history of SCD in 28 relatives of carriers without genetic data. Altogether, 21 of 28 evaluated families had a history of SCD. This suggests that truncating mutations in FLNC are associated with a high incidence of SCD.

In conclusion, large longitudinal studies investigating specific SCD-focused end-points in patients with DCM and specific rare variants are required to better inform decision-making. Currently, it appears that, in addition to carriers of LMNA mutations, carriers of a specific PLN mutation or truncating FLNC mutations should be stratified at higher risk of SCD.

Genome Wide Association Studies - DCM and SCD Risk

Given the variable penetrance and expressivity seen in DCM, the importance of genetic (and environmental) modifiers has widely been accepted. Genetic susceptibility to SCD has also been recognized with the incidence of VF in patients having an acute myocardial infarction strongly associated with a family history of SCD, independently of other traditional IHD disease variables.91 Based on these observations, genome wide association studies (GWAS) have attempted to identify novel susceptibility loci that modify an individual’s risk of developing DCM and suffering SCD. These types of studies mostly identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in non-coding DNA that are thought to affect gene expression.

A small number of loci associated with the development of DCM have been reported.92 These include a SNP within the major histocompatibility complex on chromosome 6, which has also been linked to inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis.92 The authors use this to support the hypothesis that a genetically-driven inflammatory mechanism underlies the disease in some patients.

GWAS performed in large populations of SCD patients have identified several potential loci that are associated with an individual’s risk, albeit to a modest extent.93–95 Perhaps the most promising are those associated with the BAZ2B and CXADR genes, the latter of which has been linked with the development of DCM and myocarditis.93, 95 Other groups have identified SNPs that modify electrical parameters, such as QRS and QT intervals, known as endophenotypes, which are known to influence arrhythmic risk.96 Genetic variants known to modify endophenotypes have been linked with increased arrhythmic risk in other diseases and may have similar effects in DCM.96

In summary, the scope of genetics to identify common variants that may modify SCD risk is great. However, advanced work in coronary disease has emphasized the small incremental value of each variant in isolation, and the possible need for the effects of even hundreds of variants to be combined into a model to provide a clinically useful estimation of risk in a heterogeneous disease.97

Conclusion

Existing guidelines lack sensitivity and specificity for the selection of patients with DCM for primary prevention ICD implantation. These require refinement to produce a more personalized and precise approach, with the aim of improving outcomes and cost-efficiency. Incorporating methods that identify patients at particularly high-risk of death from competing causes, who are unlikely to benefit from ICD therapy, will form an important part of this process. There is growing evidence that characteristics, other than LVEF, may be used to identify those at increased risk of SCD. Considering the multifactorial basis of ventricular arrhythmogenesis in DCM, it appears likely that an algorithm including multiple tests, which detect different pathophysiological processes involved in arrhythmia generation, may be required. LGE-CMR imaging is a routinely employed technique in the investigation of DCM, while MTWA analysis is an inexpensive additional test that is relatively simple to perform. Observational data support the ability of these techniques to identify those at high-risk of SCD. Nuclear imaging to detect autonomic dysfunction is another promising approach, however the use of this technique in current practice is limited. Although a great deal of work is needed to integrate genetic risk prediction into clinical practice, we believe the identification of high-risk rare variants, in addition to LMNA, will play an increasing role.

Multi-center, prospective registries incorporating CMR imaging, genetic, biomarker and electrophysiological data in unselected DCM cohorts should be the next step in the pursuit of improved risk stratification, with the aim of creating a multivariable risk score that can accurately discriminate between the risk of SCD and non-sudden death. Predicted annual risks of these events at which patients are most likely to gain cost-effective benefit from ICD therapy may be confirmed taking into account pre-existing clinical trial data. This should be followed by randomized trials investigating the effects of interventions, including ICD implantation, in patients deemed to be at high-risk of SCD and without an excessive risk of death from competing causes.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Cardiovascular Biomedical Research Unit at Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust and Imperial College London. Dr Halliday is supported by a British Heart Foundation Clinical Research Training Fellowship (FS/15/29/31492). Dr Goldberger received support from grant # 1R13HL132512-01 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institute of Health. Dr Prasad has received funding from British Heart Foundation, Medical Research Council, CORDA, Rosetrees and the Alexander Jansons Foundation.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Professor Cleland sits on advisory boards for Medtronic and Sorin. Dr. Goldberger is Director of the Path to Improved Risk Stratification, a not-for-profit think tank which has received unrestricted educational grants from Boston Scientific, GE Medical, Gilead, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical. Dr Prasad has received honoraria for speaking from Bayer-Schering.

References

- 1.Pinto YM, Elliott PM, Arbustini E, Adler Y, Anastasakis A, Bohm M, Duboc D, Gimeno J, de Groote P, Imazio M, Heymans S, Klingel K, Komajda M, Limongelli G, Linhart A, Mogensen J, Moon J, Pieper PG, Seferovic PM, Schueler S, Zamorano JL, Caforio AL, Charron P. Proposal for a revised definition of dilated cardiomyopathy, hypokinetic non-dilated cardiomyopathy, and its implications for clinical practice: A position statement of the ESC working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1850–1858. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hershberger RE, Hedges DJ, Morales A. Dilated cardiomyopathy: The complexity of a diverse genetic architecture. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:531–547. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bansch D, Antz M, Boczor S, Volkmer M, Tebbenjohanns J, Seidl K, Block M, Gietzen F, Berger J, Kuck KH. Primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: The cardiomyopathy trial (CAT) Circulation. 2002;105:1453–1458. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012350.99718.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strickberger SA, Hummel JD, Bartlett TG, Frumin HI, Schuger CD, Beau SL, Bitar C, Morady F. Amiodarone versus implantable cardioverter-defibrillator:Randomized trial in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy and asymptomatic nonsustained ventricular tachycardia–AMIOVIRT. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1707–1712. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, Poole JE, Packer DL, Boineau R, Domanski M, Troutman C, Anderson J, Johnson G, McNulty SE, Clapp-Channing N, Davidson-Ray LD, Fraulo ES, Fishbein DP, Luceri RM, Ip JH. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:225–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kadish A, Dyer A, Daubert JP, Quigg R, Estes NA, Anderson KP, Calkins H, Hoch D, Goldberger J, Shalaby A, Sanders WE, Schaechter A, Levine JH. Prophylactic defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2151–2158. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kober L, Thune JJ, Nielsen JC, Haarbo J, Videbaek L, Korup E, Jensen G, Hildebrandt P, Steffensen FH, Bruun NE, Eiskjaer H, Brandes A, Thogersen AM, Gustafsson F, Egstrup K, Videbaek R, Hassager C, Svendsen JH, Hofsten DE, Torp-Pedersen C, Pehrson S. Defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1221–1231. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1608029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberger JJ. Sudden cardiac death risk stratification in dilated cardiomyopathy: Climbing the pyramid of knowledge. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7:1006–1008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.002395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberger JJ, Cain ME, Hohnloser SH, Kadish AH, Knight BP, Lauer MS, Maron BJ, Page RL, Passman RS, Siscovick D, Stevenson WG, Zipes DP. Scientific statement on noninvasive risk stratification techniques for identifying patients at risk for sudden cardiac death. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:e1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorgels AP, Gijsbers C, de Vreede-Swagemakers J, Lousberg A, Wellens HJ. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest–the relevance of heart failure. The Maastricht circulatory arrest registry. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1204–1209. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stecker EC, Vickers C, Waltz J, Socoteanu C, John BT, Mariani R, McAnulty JH, Gunson K, Jui J, Chugh SS. Population-based analysis of sudden cardiac death with and without left ventricular systolic dysfunction: Two-year findings from the Oregon sudden unexpected death study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1161–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GM, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:891–975. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–327. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desai AS, Fang JC, Maisel WH, Baughman KL. Implantable defibrillators for the prevention of mortality in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2004;292:2874–2879. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.23.2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Priori SG, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm J, Elliott PM, Fitzsimons D, Hatala R, Hindricks G, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen K, Kuck KH, Hernandez-Madrid A, Nikolaou N, Norekval TM, Spaulding C, Van Veldhuisen DJ. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Europace. 2015;17:1601–1687. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golwala H, Bajaj NS, Arora G, Arora P. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for nonischemic cardiomyopathy: An updated meta-analysis. Circulation. 2017;135:201–203. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merlo M, Pyxaras SA, Pinamonti B, Barbati G, Di Lenarda A, Sinagra G. Prevalence and prognostic significance of left ventricular reverse remodeling in dilated cardiomyopathy receiving tailored medical treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1468–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schliamser JE, Kadish AH, Subacius H, Shalaby A, Schaechter A, Levine J, Goldberger JJ. Significance of follow-up left ventricular ejection fraction measurements in the defibrillators in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy treatment evaluation trial. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:838–846. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grimm W, Christ M, Bach J, Muller HH, Maisch B. Noninvasive arrhythmia risk stratification in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: Results of the Marburg cardiomyopathy study. Circulation. 2003;108:2883–2891. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000100721.52503.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poole JE, Johnson GW, Hellkamp AS, Anderson J, Callans DJ, Raitt MH, Reddy RK, Marchlinski FE, Yee R, Guarnieri T, Talajic M, Wilber DJ, Fishbein DP, Packer DL, Mark DB, Lee KL, Bardy GH. Prognostic importance of defibrillator shocks in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1009–1017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poole JE, Gleva MJ, Mela T, Chung MK, Uslan DZ, Borge R, Gottipaty V, Shinn T, Dan D, Feldman LA, Seide H, Winston SA, Gallagher JJ, Langberg JJ, Mitchell K, Holcomb R, Investigators RR Complication rates associated with pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator generator replacements and upgrade procedures: Results from the REPLACE registry. Circulation. 2010;122:1553–1561. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.976076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevenson LW. Projecting heart failure into bankruptcy in 2012? Am Heart J. 2011;161:1007–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pun PH, Al-Khatib SM, Han JY, Edwards R, Bardy GH, Bigger JT, Buxton AE, Moss AJ, Lee KL, Steinman R, Dorian P, Hallstrom A, Cappato R, Kadish AH, Kudenchuk PJ, Mark DB, Hess PL, Inoue LY, Sanders GD. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in CKD: A meta-analysis of patient-level data from 3 randomized trials. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:32–39. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levy WC, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, Sutradhar SC, Anker SD, Cropp AB, Anand I, Maggioni A, Burton P, Sullivan MD, Pitt B, Poole-Wilson PA, Mann DL, Packer M. The Seattle Heart Failure model: Prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113:1424–1433. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.584102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mozaffarian D, Anker SD, Anand I, Linker DT, Sullivan MD, Cleland JG, Carson PE, Maggioni AP, Mann DL, Pitt B, Poole-Wilson PA, Levy WC. Prediction of mode of death in heart failure: The Seattle Heart Failure Model. Circulation. 2007;116:392–398. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.687103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shadman R, Poole JE, Dardas TF, Mozaffarian D, Cleland JG, Swedberg K, Maggioni AP, Anand IS, Carson PE, Miller AB, Levy WC. A novel method to predict the proportional risk of sudden cardiac death in heart failure: Derivation of the Seattle Proportional risk model. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:2069–2077. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deo R, Norby FL, Katz R, Sotoodehnia N, Adabag S, DeFilippi CR, Kestenbaum B, Chen LY, Heckbert SR, Folsom AR, Kronmal RA, Konety S, Patton KK, Siscovick D, Shlipak MG, Alonso A. Development and validation of a sudden cardiac death prediction model for the general population. Circulation. 2016;134:806–816. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adabag S, Rector TS, Anand IS, McMurray JJ, Zile M, Komajda M, McKelvie RS, Massie B, Carson PE. A prediction model for sudden cardiac death in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:1175–1182. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmad T, Fiuzat M, Neely B, Neely ML, Pencina MJ, Kraus WE, Zannad F, Whellan DJ, Donahue MP, Pina IL, Adams KF, Kitzman DW, O’Connor CM, Felker GM. Biomarkers of myocardial stress and fibrosis as predictors of mode of death in patients with chronic heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldberger JJ, Subacius H, Patel T, Cunnane R, Kadish AH. Sudden cardiac death risk stratification in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1879–1889. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Ferrari GM, Sanzo A. T-wave alternans in risk stratification of patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy: Can it help to better select candidates for ICD implantation? Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:S29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan PS, Gold MR, Nallamothu BK. Do beta-blockers impact microvolt T-wave alternans testing in patients at risk for ventricular arrhythmias? A meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21:1009–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2010.01757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merchant FM, Ikeda T, Pedretti RF, Salerno-Uriarte JA, Chow T, Chan PS, Bartone C, Hohnloser SH, Cohen RJ, Armoundas AA. Clinical utility of microvolt T-wave alternans testing in identifying patients at high or low risk of sudden cardiac death. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:1256–1264 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldberger JJ. The coin toss: Implications for risk stratification for sudden cardiac death. Am Heart J. 2010;160:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hohnloser SH, Cohen RJ. Microvolt T-wave alternans testing provides a reliable means of guiding anti-arrhythmic therapy. Am Heart J. 2012;164:e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haugaa KH, Goebel B, Dahlslett T, Meyer K, Jung C, Lauten A, Figulla HR, Poerner TC, Edvardsen T. Risk assessment of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy by strain echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2012;25:667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Negishi K, Negishi T, Zardkoohi O, Ching EA, Basu N, Wilkoff BL, Popovic ZB, Marwick TH. Left atrial booster pump function is an independent predictor of subsequent life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;17:1153–1160. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beltrami CA, Finato N, Rocco M, Feruglio GA, Puricelli C, Cigola E, Sonnenblick EH, Olivetti G, Anversa P. The cellular basis of dilated cardiomyopathy in humans. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:291–305. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(08)80028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mewton N, Liu CY, Croisille P, Bluemke D, Lima JA. Assessment of myocardial fibrosis with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:891–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bogun FM, Desjardins B, Good E, Gupta S, Crawford T, Oral H, Ebinger M, Pelosi F, Chugh A, Jongnarangsin K, Morady F. Delayed-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in nonischemic cardiomyopathy: Utility for identifying the ventricular arrhythmia substrate. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1138–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Bakker JM, van Capelle FJ, Janse MJ, Tasseron S, Vermeulen JT, de Jonge N, Lahpor JR. Fractionated electrograms in dilated cardiomyopathy: Origin and relation to abnormal conduction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00612-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hsia HH, Marchlinski FE. Electrophysiology studies in patients with dilated cardiomyopathies. Card Electrophysiol Rev. 2002;6:472–681. doi: 10.1023/a:1021109130276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liuba I, Marchlinski FE. The substrate and ablation of ventricular tachycardia in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2013;77:1957–1966. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-13-0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gulati A, Jabbour A, Ismail TF, Guha K, Khwaja J, Raza S, Morarji K, Brown TD, Ismail NA, Dweck MR, Di Pietro E, Roughton M, Wage R, Daryani Y, O’Hanlon R, Sheppard MN, Alpendurada F, Lyon AR, Cook SA, Cowie MR, Assomull RG, Pennell DJ, Prasad SK. Association of fibrosis with mortality and sudden cardiac death in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. JAMA. 2013;309:896–908. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Assomull RG, Prasad SK, Lyne J, Smith G, Burman ED, Khan M, Sheppard MN, Poole-Wilson PA, Pennell DJ. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance, fibrosis, and prognosis in dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1977–1985. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neilan TG, Coelho-Filho OR, Danik SB, Shah RV, Dodson JA, Verdini DJ, Tokuda M, Daly CA, Tedrow UB, Stevenson WG, Jerosch-Herold M, Ghoshhajra BB, Kwong RY. CMR quantification of myocardial scar provides additive prognostic information in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:944–954. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuruvilla S, Adenaw N, Katwal AB, Lipinski MJ, Kramer CM, Salerno M. Late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance predicts adverse cardiovascular outcomes in nonischemic cardiomyopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:250–258. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.001144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Disertori M, Rigoni M, Pace N, Casolo G, Mase M, Gonzini L, Lucci D, Nollo G, Ravelli F. Myocardial fibrosis assessment by LGE is a powerful predictor of ventricular tachyarrhythmias in ischemic and nonischemic LV dysfunction: A meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:1046–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Masci PG, Doulaptsis C, Bertella E, Del Torto A, Symons R, Pontone G, Barison A, Droogne W, Andreini D, Lorenzoni V, Gripari P, Mushtaq S, Emdin M, Bogaert J, Lombardi M. Incremental prognostic value of myocardial fibrosis in patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy without congestive heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:448–456. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perazzolo Marra M, De Lazzari M, Zorzi A, Migliore F, Zilio F, Calore C, Vettor G, Tona F, Tarantini G, Cacciavillani L, Corbetti F, Giorgi B, Miotto D, Thiene G, Basso C, Iliceto S, Corrado D. Impact of the presence and amount of myocardial fibrosis by cardiac magnetic resonance on arrhythmic outcome and sudden cardiac death in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:856–863. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leyva F, Taylor RJ, Foley PW, Umar F, Mulligan LJ, Patel K, Stegemann B, Haddad T, Smith RE, Prasad SK. Left ventricular midwall fibrosis as a predictor of mortality and morbidity after cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1659–1667. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Di Marco A, Anguera I, Schmitt M, Klem I, Neilan T, White JA, Sramko M, Masci PG, Barison A, McKenna P, Mordi I, Haugaa KH, Leyva F, Rodriguez Capitan J, Satoh H, Nabeta T, Dallaglio PD, Campbell NG, Sabate X, Cequier A. Late gadolinium enhancement and the risk for ventricular arrhythmias or sudden death in dilated cardiomyopathy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Halliday BP, Gulati A, Ali A, Guha K, Newsome S, Arzanauskaite M, Vassiliou VS, Lota A, Izgi C, Tayal U, Khalique Z, Stirrat C, Auger D, Pareek N, Ismail TF, Rosen SD, Vazir A, Alpendurada F, Gregson J, Frenneaux MP, Cowie MR, Cleland JGF, Cook SA, Pennell DJ, Prasad SK. Association between mid-wall late gadolinium enhancement and sudden cardiac death in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and mild and moderate left ventricular systolic dysfucntion. Circulation. 2017;135 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026910. [epub ahead of print] DOI: https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Al-Khatib SM, Han JY, Edwards R, Bardy GH, Bigger JT, Buxton AE, Cappato R, Dorian P, Hallstrom A, Kadish AH, Kudenchuk PJ, Lee KL, Mark DB, Moss AJ, Steinman R, Inoue LY, Sanders GD. Do patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction between 30% and 35% benefit from a primary prevention implantable cardioverter defibrillator? Int J Cardiol. 2014;172:253–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arbustini E, Disertori M, Narula J. Primary prevention of sudden arrhythmic death in dilated cardiomyopathy: Current guidelines and risk stratification. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Souders CA, Bowers SL, Baudino TA. Cardiac fibroblast: The renaissance cell. Circ Res. 2009;105:1164–1176. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.209809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Flett AS, Hayward MP, Ashworth MT, Hansen MS, Taylor AM, Elliott PM, McGregor C, Moon JC. Equilibrium contrast cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the measurement of diffuse myocardial fibrosis: Preliminary validation in humans. Circulation. 2010;122:138–144. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.930636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.aus dem Siepen F, Buss SJ, Messroghli D, Andre F, Lossnitzer D, Seitz S, Keller M, Schnabel PA, Giannitsis E, Korosoglou G, Katus HA, Steen H. T1 mapping in dilated cardiomyopathy with cardiac magnetic resonance: Quantification of diffuse myocardial fibrosis and comparison with endomyocardial biopsy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:210–216. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeu183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miller CA, Naish JA, Bishop P, Coutts G, Clark D, Zhao S, Ray SG, Yonan N, Williams SG, Flett AS, Moon JC, Greiser A, Parker GJM, Schmitt S. Comprehensive validation of cardiovascular magnetic resonance techniques for the assessment of myocardial extracellular volume. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:373–383. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.000192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Puntmann VO, Carr-White G, Jabbour A, Yu CY, Gebker R, Kelle S, Hinojar R, Doltra A, Varma N, Child N, Rogers T, Suna G, Arroyo Ucar E, Goodman B, Khan S, Dabir D, Herrmann E, Zeiher AM, Nagel E. T1-mapping and outcome in nonischemic cardiomyopathy: All-cause mortality and heart failure. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen Z, Sohal M, Voigt T, Sammut E, Tobon-Gomez C, Child N, Jackson T, Shetty A, Bostock J, Cooklin M, O’Neill M, Wright M, Murgatroyd F, Gill J, Carr-White G, Chiribiri A, Schaeffter T, Razavi R, Rinaldi CA. Myocardial tissue characterization by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging using T1 mapping predicts ventricular arrhythmia in ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:792–801. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lopez B, Gonzalez A, Ravassa S, Beaumont J, Moreno MU, San Jose G, Querejeta R, Diez J. Circulating biomarkers of myocardial fibrosis: The need for a reappraisal. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:2449–2456. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Querejeta R, Varo N, Lopez B, Larman M, Artinano E, Etayo JC, Martinez Ubago JL, Gutierrez-Stampa M, Emparanza JI, Gil MJ, Monreal I, Mindan JP, Diez J. Serum carboxy-terminal propeptide of procollagen type I is a marker of myocardial fibrosis in hypertensive heart disease. Circulation. 2000;101:1729–1735. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.14.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vergaro G, Del Franco A, Giannoni A, Prontera C, Ripoli A, Barison A, Masci PG, Aquaro GD, Cohen Solal A, Padeletti L, Passino C, Emdin M. Galectin-3 and myocardial fibrosis in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2015;184:96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kanoupakis EM, Manios EG, Kallergis EM, Mavrakis HE, Goudis CA, Saloustros IG, Milathianaki ME, Chlouverakis GI, Vardas PE. Serum markers of collagen turnover predict future shocks in implantable cardioverter-defibrillator recipients with dilated cardiomyopathy on optimal treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2753–2759. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zipes DP, Levy MN, Cobb LA, Julius S, Kaufman PG, Miller NE, Verrier RL. Sudden cardiac death. Neural-cardiac interactions. Circulation. 1987;76:202–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goldberger JJ, Hendel RC. Decision making for implantable cardioverter defibrillator implantation: Is there a role for neurohumoral imaging? Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:e004275. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.004275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Merlet P, Benvenuti C, Moyse D, Pouillart F, Dubois-Rande JL, Duval AM, Loisance D, Castaigne A, Syrota A. Prognostic value of mibg imaging in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:917–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sood N, Al Badarin F, Parker M, Pullatt R, Jacobson AF, Bateman TM, Heller GV. Resting perfusion mpi-spect combined with cardiac 123i-mibg sympathetic innervation imaging improves prediction of arrhythmic events in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy patients: Sub-study from the ADMIRE-HF trial. J Nucl Cardiol. 2013;20:813–820. doi: 10.1007/s12350-013-9750-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jacobson AF, Senior R, Cerqueira MD, Wong ND, Thomas GS, Lopez VA, Agostini D, Weiland F, Chandna H, Narula J, Investigators AH Myocardial iodine-123 meta-iodobenzylguanidine imaging and cardiac events in heart failure. Results of the prospective ADMIRE-HF study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2212–2221. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]