Abstract

Rationale

Calmodulinopathies comprise a new category of potentially life-threatening genetic arrhythmia syndromes capable of producing severe long QT syndrome (LQTS) with mutations involving either CALM1, CALM2, or CALM3. The underlying basis of this form of LQTS is a disruption of Ca2+/CaM-dependent inactivation (CDI) of L-type Ca2+ channels (LTCCs).

Objective

To gain insight into the mechanistic underpinnings of calmodulinopathies and devise new therapeutic strategies for the treatment of this form of LQTS.

Methods and Results

We generated and characterized the functional properties of iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) from a patient with D130G-CALM2-mediated LQTS, thus creating a platform with which to devise and test novel therapeutic strategies. The patient-derived iPSC-CMs display (1) significantly prolonged action potentials (APs), (2) disrupted Ca2+ cycling properties, and (3) diminished CDI of LTCCs. Next, taking advantage of the fact that calmodulinopathy patients harbor a mutation in only one of six redundant CaM-encoding alleles, we devised a strategy using CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) to selectively suppress the mutant gene while sparing the wild-type counterparts. Indeed, suppression of CALM2 expression produced a functional rescue in iPSC-CMs with D130G-CALM2, as shown by the normalization of AP duration and CDI following treatment. Moreover, CRISPRi can be designed to achieve selective knockdown of any of the three CALM genes, making it a generalizable therapeutic strategy for any calmodulinopathy.

Conclusions

Overall, this therapeutic strategy holds great promise for calmodulinopathy patients as it represents a generalizable intervention capable of specifically altering CaM expression and potentially attenuating LQTS-triggered cardiac events, thus initiating a path towards precision medicine.

Keywords: Long-QT syndrome, Calmodulin, L-type calcium channels, Ca2+-CaM-dependent inactivation (CDI), induced-pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)

Subject Terms: Ion Channels/Membrane Transport, Electrophysiology, Stem Cells, Gene Therapy, Arrhythmias

INTRODUCTION

An increasingly recognized group of patients suffer from diseases called calmodulinopathies, caused by missense mutations in calmodulin (CaM), a ubiquitous Ca2+ sensor vital to immune system, heart, and brain function. Calmodulinopathy patients often experience life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias associated with long QT syndrome (LQTS)1–4, catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT)3, 5, and idiopathic ventricular fibrillation (IVF)6. Their symptoms are often resistant to conventional therapy, suggesting alternate underlying disease mechanisms which require novel therapeutic strategies.

LQTS-associated CaM mutations are known to alter the Ca2+/CaM binding affinity2, implicating a myriad of Ca2+/CaM binding partners as potential pathogenic elements. The L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC), which plays a vital role in LQTS, represents one such target7–10. In fact, LQTS-associated calmodulinopathy mutations (D96V, D130G, and F142L) mediate a decrease in Ca2+/CaM-dependent inactivation (CDI) of LTCCs, a critical form of channel regulation8. This would result in the failure of calmodulinopathy-affected LTCCs to inactivate during the plateau of the cardiac action potential (AP), and is predicted to prolong the AP duration (APD), a cellular correlate of prolonged QT intervals identified on the electrocardiogram10, 11.

There are three distinct calmodulin genes, CALM1 (chr14q31), CALM2 (chr2p21), and CALM3 (chr19q13), with 85% nucleotide sequence homology that encode for completely identical 149 amino-acid CaM proteins. In all reported cases of LQTS-associated calmodulinopathies, the mutation occurs heterozygously in one of these three redundant CALM genes, i.e. with only one out of six alleles harboring the mutation. Thus, only a small fraction of mutant CaM protein causes the severe phenotype. This large dominant negative effect may be rationalized by the known pre-association of Ca2+-free CaM to the LTCCs10, 12. In fact, the reduction of CDI due to mutant CaM expression corresponds to a highly non-linear effect such that a relatively small amount of mutant CaM can significantly decrease CDI in HEK293 cells10. However, this phenomenon remains to be substantiated in a cardiac system under conditions mimicking that of a calmodulinopathy patient. To this end, we generated induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from a patient harboring a heterozygous p.D130G-CaM mutation1 resulting from a single nucleotide substitution (c.389 A>G) within the CALM2 gene. Cardiomyocytes (CMs) differentiated from these cells (iPSC-CMs) offer an ideal platform for exploring the dominant negative effect of mutant CaM within a patient-specific genetic background and provide a model system with which to understand the pathogenesis and treatment options of CaM-mediated LQTS.

The non-linear CDI effect in calmodulinopathies may also provide an opportunity for novel therapeutic interventions. Impaired repolarization resulting from a deficit of LTCC CDI exhibits a non-linear threshold such that the fraction of channels harboring a CDI deficit can increase without overt electrical dysfunction up to a critical threshold. At this point, addition of even a minute fraction of affected channels generates the substrate for flagrant arrhythmogenesis8. Should this threshold behavior hold true, a relatively small decrease in mutant CaM could result in a significant increase in electrical stability and thus lead to substantial clinical improvement. To this end, we exploit the precise genetic control of a variant of CRISPR/Cas9 technology, CRISPR interference (CRISPRi)13–15, to selectively down-regulate mutant CaM expression without permanently altering the genome. Taking advantage of the fact that patients with calmodulinopathies harbor mutations in only one of three CALM genes, mutant CaM could be attenuated while largely sparing wild-type CaM. As a test bed for therapeutic development, we utilize our D130G-CaM containing iPSC-CMs (iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs), as these cells are able to form a functional syncytium with the genetic background of the patient. Such a disease model readily permits application of CRISPRi to down-regulate mutant CALM genes and enables analysis of the functional effects of such a manipulation.

In this study, we demonstrate that iPSC-CMs derived from a patient harboring the p.D130G-CaM missense mutation within CALM2 accurately recapitulate the cellular LQTS phenotype. Specifically, the iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs demonstrate prolonged APs, disrupted Ca2+ cycling, and diminished LTCC CDI, consistently across extended culture time. Having established a viable model system, we next use CRISPRi to selectively silence the expression of the CALM2 gene (both mutant and wild-type CALM2 alleles) and correlate this reduction with a functional rescue of the iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs. In particular, we have corrected fully the magnitude of CDI in these cells, resulting in normalization of the AP profile and therapeutic attenuation of the APD.

METHODS

Study participant

A p.D130G-CaM missense mutation secondary to c.389 A>G-CALM2 was identified previously in a young female patient with severe LQTS that was referred to the Windland Smith Rice Sudden Death Genomics Laboratory (M.J.A.) at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN for research-based genetic testing1. This study was approved by the Mayo Foundation Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained.

Generation of iPSCs

Dermal fibroblasts were isolated from a punch skin biopsy obtained from the p.D130G-CaM positive patient and expanded in DMEM containing 10% FBS. These fibroblasts were reprogrammed using the CytoTune-iPS 2.0 Sendai Reprogramming Kit (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Colonies were isolated as separate clones and characterized for pluripotency based on immunofluorescent staining (Online Figures. I, II).). Sanger sequencing of genomic DNA of each clone confirmed a heterozygous mutation c.389 A>G-CALM2. Wild-type iPSCs used for control experiments were a generous gift from Dr. Bruce Conklin16. All cell lines were tested negative for mycoplasma.

Cell culture

IPSCs were cultured and differentiated in a feeder-free and xeno-free system using a modified protocol described previously17. Briefly, iPSCs were cultured on Geltrex matrix (Gibco)-coated tissue culture plates and fed daily with Essential 8 medium (Gibco). When cells were ~30% confluent, they were mechanically dissociated using 0.5 mmol/L EDTA in Dulbecco`s Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS). For differentiation into cardiomyocytes, cells were dissociated and plated on fresh Geltrex matrix-coated plates. When confluent (day 0), media was exchanged with RPMI-1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with B-27(-insulin) (Gibco) and 6 µmol/L CHIR99021. Cells were maintained in this media for the first 7 days, with medium exchange every 2 days. On day 3, 5 µmol/L IWR-1 was added. On day 7, media was changed to RPMI-1640 with B-27 supplement (Gibco) and was exchanged every 2 days. Spontaneous contraction of iPSC-CMs was observed by day 12.

12–14 days post-differentiation, sheets of contracting iPSC-CMs were dissociated using 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco). The isolated cells were pre-plated for 4–8 min on Geltrex-coated tissue culture plates in order to decrease the number of non-cardiac cells, and the non-adherent cells were then plated on Geltrex matrix-coated glass coverslips at ~2.5×104 cells/cm2 for electrophysiological studies and ~3×105 cells/cm2 on plastic coverslips to create monolayers for imaging.

CRISPRi construction, transfection, and transduction

The lentiviral transfer vectors containing cDNA for enzymatically dead Cas9 fused with suppressor Krüppel-associated box (KRAB) and blue florescence protein (BFP) (pHR-SFFV-dCas9-BFP-KRAB) was purchased from Addgene (Plasmid #46911). BFP was replaced with monomeric ruby red fluorescence protein (mRuby). The entire construct (dCas9-mRuby-KRAB) was then cloned via Gibson assembly (New England Biolabs) into the lentiviral vector pRRLsin18.cPPT.CMV.eGFP.Wpre5418. The lentiviral vector (pKLV-U6gRNA(BbsI)-PGKpuro2ABFP) containing cDNA for the gRNA backbone (driven by the human U6 promoter) and a BFP marker (driven by PGK promoter) was purchased from Addgene (Plasmid #50946) and BFP was replaced with cyan fluorescence protein (CFP). E-CRISPR gRNA sequence prediction program19 was used to generate candidate gRNA sequences that selectively complement to the human CALM2 gene (Online Table I). The candidate gRNA sequences were then cloned into the aforementioned lentiviral transfer vector using Golden Gate assembly.

For gRNA screening, both dCas9-mRuby-KRAB and candidate gRNA were expressed in HEK293 cells by transfection with polyethylenimine10. For iPSC-CM transduction, lentivirus was generated using Lenti-X-Concentrator (Clontech) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations and added to monolayers on day 21 post-differentiation. Expression was confirmed by mRuby and CFP visualization.

MRNA expression

Total RNA was extracted 4 days post-transfection in HEK293 cells and 8-9 days post-transduction in iPSC-CMs using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Complementary DNA was made using the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantification of CALM mRNA levels was performed using real time PCR (qPCR) with TaqMan gene expression assay (Applied Biosystems). CALM expression level was normalized to the expression level of a house-keeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Probe numbers: CALM1; Hs00300085_s1, CALM2; Hs00830212_s1, CALM3; Hs00968732_g1, and GAPDH; Hs02758991_g1.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell recordings of iPSC-CMs were performed 28-30 days post-differentiation at room temperature using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments). Traces were lowpass filtered at 2 kHz, and digitally sampled at 10 kHz. P/8 leak subtraction was used, with series resistances of 1-2 MΩ. Internal solutions contained, (in mmol/L): CsMeSO3, 114; CsCl, 5; MgCl2, 1; MgATP, 4; HEPES (pH 7.3), 10; BAPTA, 10; and ryanodine, 0.005; at 295 mOsm adjusted with CsMeSO3. Seals were formed in Tyrode's solution containing (in mmol/L): NaCl, 135; KCl, 5.4; CaCl2, 1.8; MgCl2, 0.33; NaH2PO4, 0.33; HEPES, 5; glucose, 5 (pH 7.4). Following patch rupture, bath solution was switched to Ca2+- or Ba2+- external solution containing (in mmol/L): TEA-MeSO3, 140; HEPES (pH 7.4), 10; and CaCl2 or BaCl2, 5 (for 30-day-old iPSC-CMs) or 40 (for 60-day-old iPSC-CMs); at 300 mOsm, adjusted with TEA-MeSO3. The extent of CDI after a 50-ms depolarization (f50) was calculated as:

| (1) |

where r50/Ba and r50/Ca are currents remaining after 50-ms with Ba2+- and Ca2+-containing external solution.

Imaging

Monolayers of iPSC-CMs expressing either a genetically encoded voltage or Ca2+ sensor (ASAP120 or GCaMP6f21 respectively via lentiviral transduction) were paced using a custom field stimulation apparatus in RPMI-1640 medium with B-27 supplement. Expression efficiency of the genetically encoded sensors was assessed via flow cytometry (Online Figure III). At 30, 45, and 60 days post-differentiation, green fluorescence was imaged with an Evolve 512delta camera at ≥ 190 frames per second and the relative change in fluorescence signal was measured. The time from upstroke to 80% repolarization (APD80) was used to index the APD while the magnitude of peak transient, time to peak, and decay time constant were used as metrics for CaTs. All metrics were quantified using custom Matlab (Mathworks) scripts. For all experiments involving treatment with CRISPRi, control cells were recorded on the same day and were from the same culture, minimizing any culture dependent variability of the cells.

Statistical analysis

All parameters are shown as mean ± SEM. Technical and biological replicates are indicated in the figure legend. The D'Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test was used to confirm a normal distribution prior to application of the statistical test for comparison of means. Data which did not initially correspond to a normal distribution were logarithmically transformed. The F-test was used to compare variances and a two-sided Student's t-test (adjusted for unequal variance where applicable) was used to compare the difference in means across sample groups. Reported p values are from the two-sided Student's t-test. Minimal sample size to ensure adequate power was determined as previously described22.

RESULTS

Proband identification and generation of mutation-harboring iPSCs

An increasing number of patients are being diagnosed with calmodulinopathies resulting from single heterozygous missense mutations within their CALM1, CALM2, or CALM3 genes. Here, we focus on a p.D130G-CaM mutation identified within CALM2 of a female infant with severe LQTS1. The proband was born at term, and noted to have bradycardia (Figure 1). An ECG, recorded 12 hours after birth, revealed a QTc of 740 ms and 2:1 atrioventricular block (Figure 1A). She was treated with beta-blockers, phenytoin, spironolactone, potassium, and placement of a single-chamber pacemaker within the first week of life. At 6-years-old, a single-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillator was implanted and beta-blocker therapy was continued. At 11 and 14 years old, she experienced appropriate defibrillator discharges for ventricular fibrillation.

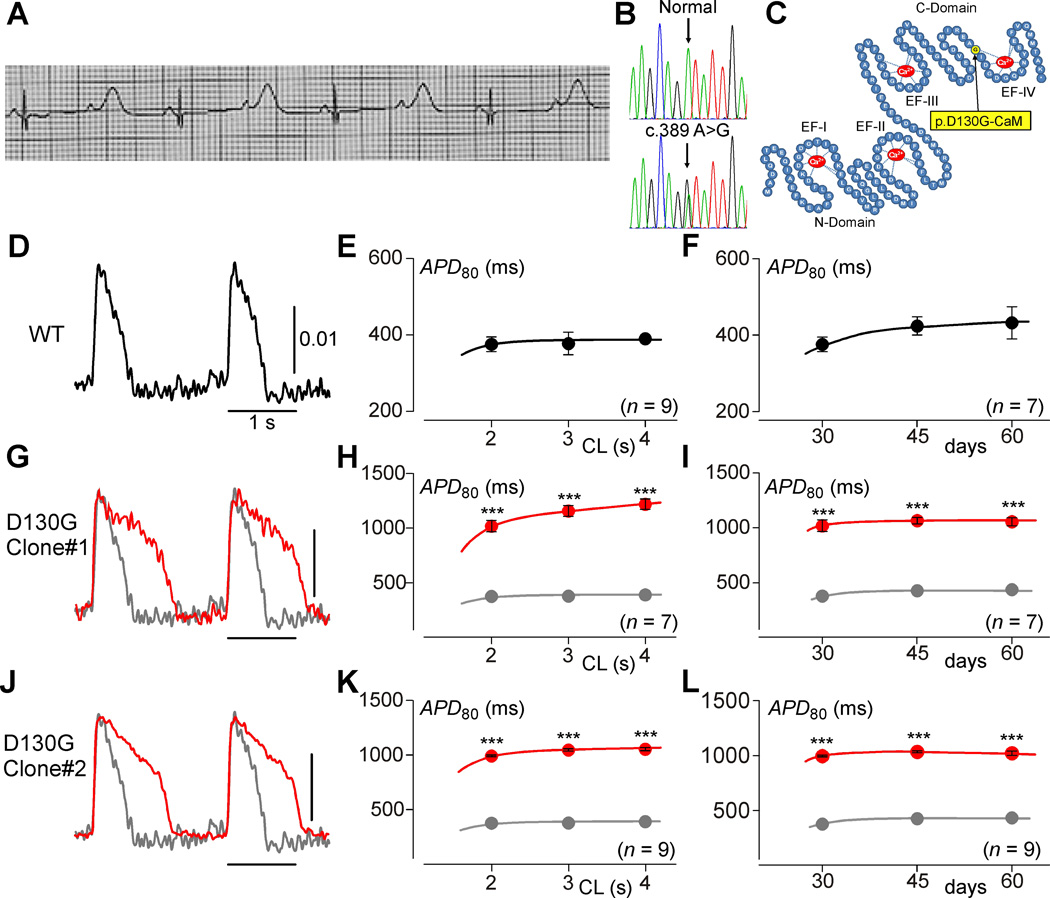

Figure 1. IPSCs recapitulate the calmodulinopathy phenotype.

A, The proband’s electrocardiogram taken at 12 hours after birth, illustrating a QTc>700 ms. B, DNA Sanger sequencing chromatograms for both a normal control (top) and the patient (bottom) revealing a heterozygous c.389 A>G single nucleotide substitution in CALM2 resulting in the p.D130G-CaM amino acid substitution. C, Schematic rendering of the CaM protein (blue) highlighting the N-domain and C-domain, each containing two EF hands (labeled EF-I through EF-IV) with Ca2+ (red) bound. Yellow circle indicates the D130G mutation identified in the LQTS patient. D, Exemplar APs from iPSCWT-CMs (WT) paced at 0.5 Hz, recorded via fluorescence imaging using ASAP1. Scale bar indicates change in fluorescence as measured by ΔF/F0. E, Population data for mean APDs at various pacing cycle lengths (CL) for iPSCWT-CMs (n=9). Error bars indicate ±SEM throughout. Each biological replicate (n) is an average value of 2 technical replicates, here and throughout this figure. F, Population data for iPSCWT-CM APDs at a 2-second cycle length across multiple time points (n=9, 9, and 7 on day 30, 45, and 60, respectively). G, Exemplar APs from iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs (red). WT reproduced in gray. H, Average APD data for iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs (red) (n=7). WT reproduced in gray (*** p<0.001 compared to WT; corrected for unequal variance of normal distributions). I, Average APDs at a 2-second cycle length from D130G iPSCs are stable across time (n=7, 7, and 7 on day 30, 45, and 60, respectively). J–L, Alternate D130G clone demonstrating the same result as G–I (n=9, *** p<0.001 compared to WT and corrected for unequal variance of normal distributions).

Next-generation whole exome sequencing followed by CALM1, CALM2, and CALM3 gene-specific analysis identified a p.D130G-CaM mutation (c.389 A>G, CALM2) within the patient (Figure 1B). The mutation maps to an EF-hand within CaM (Figure 1C) and, like other calmodulinopathic mutations, causes a reduction in the Ca2+ binding affinity2. In order to create a model system with which to understand the pathogenesis and treatment options for this type of CaM-mediated LQTS, multiple clones of iPSCs were generated from the patient’s skin biopsy. Two clones with normal karyotypes at passage 25 and expressing the pluripotency markers (Nanog, Oct4, and SSEA4) were selected (Online Figure I). In addition, the ability to generate each of the three germ layers was confirmed by staining differentiated embryoid bodies for α-fetoprotein (endoderm), smooth muscle actin (mesoderm), and glial fibrillary acidic protein (ectoderm) and by analysis of teratoma formation (Online Figure II). Monolayers of iPSC-CMs (iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs) were then generated from these two clones of iPSCs.

To confirm that the background of these iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs was not significantly different than iPSCs derived from healthy individuals, we quantified the mRNA levels for multiple proteins that could potentially alter cardiac action potential morphology and/or EC coupling. Compared to wild-type iPSC-CMs (iPSCWT-CMs), we found no difference in the mRNA levels of CALM1, CALM2, CALM3, CACNA1C, KCNH2, NCX1, SCN5A, PLN or SERCA2 (Online Figure IV). Only KCNQ1 and RYR2 appeared somewhat elevated in the iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs; however, this variation would not be expected to contribute to a LQT phenotype. Importantly, this validates our iPSCWT-CMs as a relevant control, despite the potential variability which can occur due to differing genetic backgrounds23.

Altered APs and calcium transients (CaTs) in iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs

Previous work has linked mutations in CaM with LQTS; however, direct evidence demonstrating AP prolongation due to the D130G-CaM mutation has yet to be shown in human cardiomyocytes. We therefore characterized the iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs in order to confirm that these cells exhibit prolonged APDs that typically underlie LQTS. To measure APDs, the monolayers were transduced with the genetically encoded voltage sensor ASAP1, which features rapid kinetics and stable long-term expression, allowing accurate APD measurements over multiple time points20. The resultant APDs (Figures 1D, E) measured from wild-type iPSC-CMs (iPSCWT-CMs) were comparable to those previously reported (Online Table I)16, 24. Under these same conditions, iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs exhibited dramatically longer APs and APDs (Figures 1G, J; red) as compared to their WT counterparts (gray). This result could be observed at multiple pacing frequencies (Figures 1H, K), a feature associated with increased arrhythmogenic risk25. Moreover, the phenotype was stable over long periods of time in culture, such that APDs measured at 30 days in culture were not significantly different than those measured after 45 days or 60 days (Figures 1F, I, L; Online Figure VI).

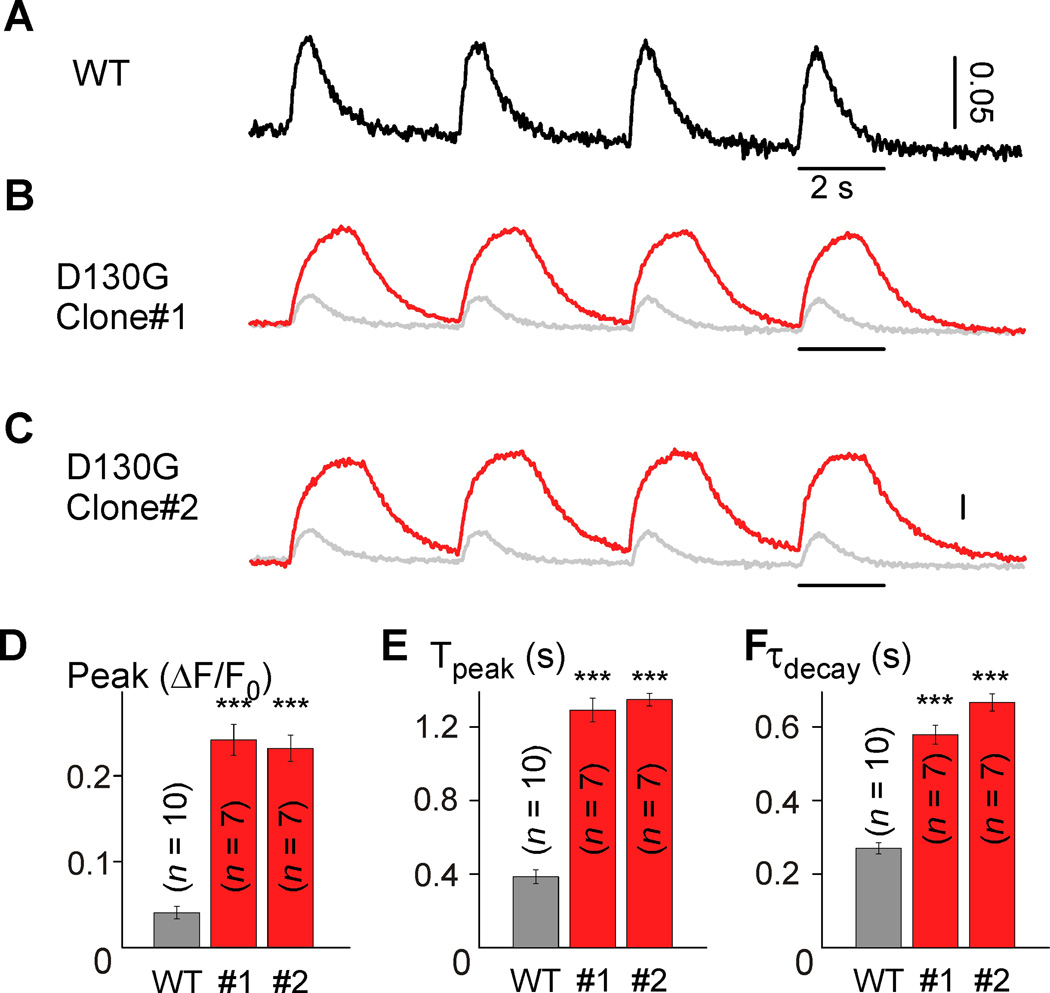

In addition to the electrical disturbance, dysfunctions in Ca2+ cycling are often associated with arrhythmogenesis in LQTS26. As such, we examined the intracellular Ca2+ transients (CaTs) of iPSC-CMs using GCaMP6f, a genetically encoded Ca2+ sensor with a high signal-to-noise ratio and fast kinetics21. Figure 2A shows the CaTs from a monolayer of iPSCWT-CMs paced at 0.25 Hz with the rise and decay kinetics comparable to those previously reported27. However, monolayers of iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs exhibit CaT amplitudes over three times larger than WT with slower rise and decay kinetics (Figures 2B–F), akin to the phenotype observed in CaMD130G-overexpressing rodent myocytes10, 11. Likewise, these CaT effects were stable over time (Online Figure VII). While SR content of the iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs was not significantly different from the WT myocytes (Online Figure VIII), the trend was in the direction of increased SR Ca2+. Thus, the patient-derived iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs recapitulate the LQTS phenotype, demonstrating significant proarrhythmic potential despite limited, native expression levels of CaMD130G.

Figure 2. Disruption of calcium handling in calmodulinopathy iPSCs.

A, Exemplar CaTs recorded from iPSCWT-CMs (WT) using GCaMP6f. Scale bar indicates change in fluorescence as measured by ΔF/F0. B, Exemplar CaTs recorded from iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs (red) as compared to WT (gray). C, Exemplar CaTs from an alternate D130G clone. D–F, Population data demonstrating larger amplitude and slower kinetics for both iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs clones (red) (Peak, mean peak fluorescence change; Tpeak, mean time to peak; τdecay, mean decay time constant; *** p<0.001 compared to WT and corrected for unequal variance, all populations were normally distributed). Error bars indicate ± SEM throughout. Biological replicates (n) are 10, 7, and 7 for WT, D130G clone #1, D130G clone#2, respectively. Each biological replicate (n) is an average value of 2 technical replicates.

IPSCD130G-CaM-CMs exhibit diminished CDI

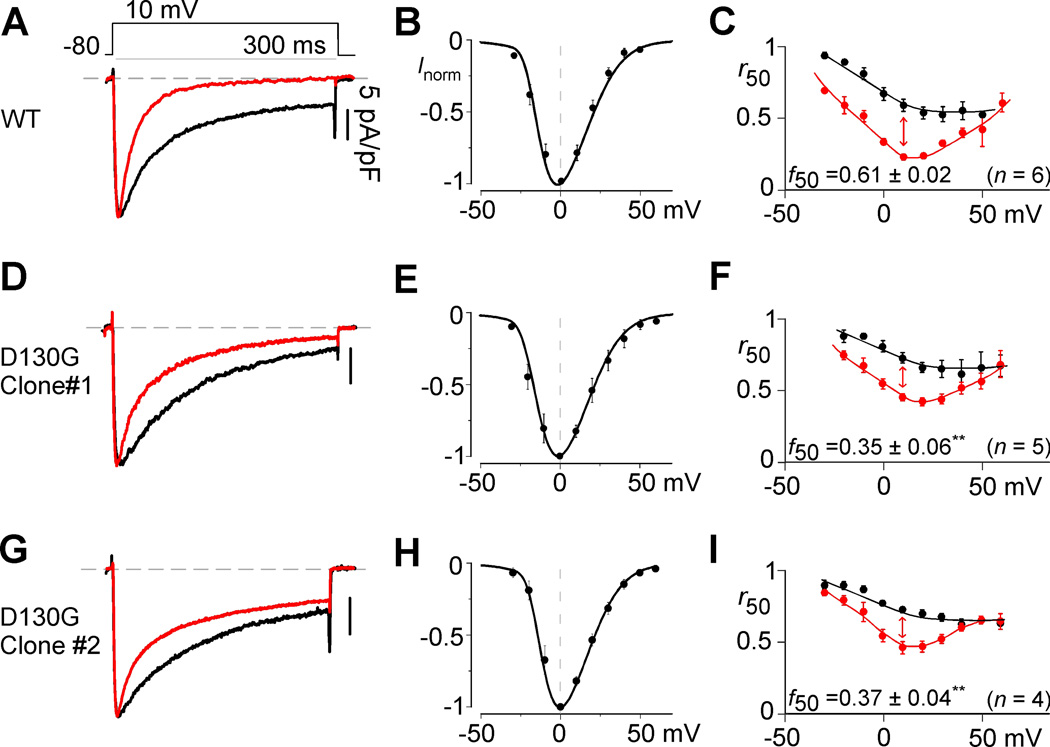

Previous studies have implicated the cardiac LTCC as a major contributor to the LQT phenotype in patients with CaM-mediated LQTS10, 11. In particular, the D130G mutation weakens the affinity of Ca2+ binding to CaM2, resulting in a significant decrease in CDI when CaMD130G is overexpressed in rodent myocytes10, 11. However, the relevance of these results remains to be established in human CMs with physiological levels of mutant CaM expression. We therefore examined the effect of the D130G mutation on LTCC CDI in patient-derived iPSC-CMs. To this end, we performed whole-cell patch clamp recordings of individual CMs. IPSCWT-CMs exhibited a rapid decay in their Ca2+ current in response to a 10-mV depolarizing step (Figure 3A, red). To isolate the extent of pure CDI, Ba2+, which binds poorly to CaM, was used as the charge carrier to gauge the extent of voltage-dependent inactivation (VDI) within the same cell10. CDI can be seen as the excess inactivation of the Ca2+ trace (Figure 3A; red), as compared to the Ba2+ trace (black). Population data showing the average normalized peak Ba2+ currents as a function of voltage is shown in Figure 3B. For CDI quantification, we first measure the fraction of current remaining after 50 ms (r50) for both the Ca2+ and Ba2+ currents. By plotting the r50 values as a function of voltage, a hallmark U-shaped relationship is observed with Ca2+ as the charge carrier (Figure 3C, red). The difference between the Ba2+ and Ca2+ r50 values at 10 mV, normalized by the Ba2+ r50 value, quantifies the extent of pure CDI (Figure 3C). Applying this same protocol to the iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs reveals a profound attenuation in the kinetics and extent of CDI (Figures 3D, G) without altering the voltage activation profile (Figures 3E, H). Quantifying this result across voltages (Figures 3F, I) confirms a significant decrease in CDI (red, p<0.01), an effect which is maintained over time in culture (Online Figure IX). Importantly, this reduction of CDI is significant even in the iPSCD130G-CaM-CM background, where the patient’s other five CALM alleles are WT. Thus, these iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs not only provide a viable model system for this LQTS-associated calmodulinopathy, but also suggest that the loss of LTCC CDI is a significant underlying mechanism leading to arrhythmogenesis in these patients.

Figure 3. CDI deficits in calmodulinopathy iPSCs.

A, Exemplar whole-cell current recordings in Ca2+ (red) and Ba2+ (black) for iPSCWT-CMs. Ba2+ current is normalized to Ca2+ peak, scale bar corresponds to Ca2+ here and throughout. B, Mean normalized current and voltage relationship obtained in Ba2+ for iPSCWT-CMs. Error bars indicate ± SEM throughout. C, Population data for Ca2+ (red) and Ba2+ (black) for iPSCWT-CMs, where r50 quantifies the extent of current inactivation across voltages. Red arrow depicts extent of CDI (f50) at 10-mV test potential here and throughout (n=6 separate cells for B–C). D, Exemplar whole-cell current recordings in Ca2+ (red) and Ba2+ (black) for iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs (n=5). E, There is no significant shift (p>0.05 compared to WT) in the current voltage relationship for iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs as compared to WT B. F, Population data demonstrates a significant decrease in CDI for the iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs (**p<0.01 compared to WT, corrected for unequal variance). G–I, Alternate D130G clone (n=4) demonstrating the same result as D–F.

To further bolster this LTCC centric hypothesis, we examined the effects of other potential CaM targets which might contribute to the LQT phenotype of calmodulinopathy patients. To date, only three genetic forms of LQTS result from mutations within a channel known to be modulated by CaM. LQT1 results from loss of function mutations in KCNQ1, LQT3 results from gain-of-function mutations in SCN5A, and LQT8 is caused by inactivation altering mutations within CACNA1C, somewhat mirroring the LTCC effects described in this study. Of these forms of LQT, only LQT8 approaches the extreme APD prolongation seen in calmodulinopathy patients28, 29. To corroborate this in our model system, we mimicked the effect of each LQT mechanism pharmacologically. Consistent with clinical findings, enhancement of the current through the LTCC had a profound effect on APD, while blocking IKS or enhancing NaV1.5 produced more modest APD prolongation (Online Figure X). We next utilized a validated model of an adult mammalian cardiomyocyte8, 30–32 to investigate the fraction of channels harboring a CaMD130G required to produce electrical instability via and LTCC CDI specific mechanism in silico (Online Figure XI). Indeed, only a small fraction of channels harboring CaMD130G was necessary to achieve significant arrhythmogenesis in the model cells. Importantly, the simulation predicted a threshold for the induction of electrical instability precisely matching the expected levels of mutant CaM expression in calmodulinopathy patients based on reported CALM gene expression33. Such a threshold highlights an important therapeutic principle; namely, only a small reduction in the expression levels of the mutant CaM may be needed to provide significant clinical benefit to patients.

Toward a new therapeutic strategy

Having confirmed a major role for LTCC CDI deficits in generating the LQT phenotype in this calmodulinopathy patient, we next considered the implications of this mechanism on a novel therapeutic intervention. As our results predict a significant functional benefit conferred by even a small shift in the expression of mutant versus WT CaM (Online Figure XI), we sought to reduce the fraction of mutant CaM expressed in patients with CaM-mediated LQTS. As all three CALM genes encode for identical CaM proteins, we reasoned that we might be able to take advantage of the sequence variation at the nucleotide level. We thus utilized CRISPRi13–15 to decrease the transcription of the CALM2 alleles, both the WT and the D130G-containing CALM2 alleles.

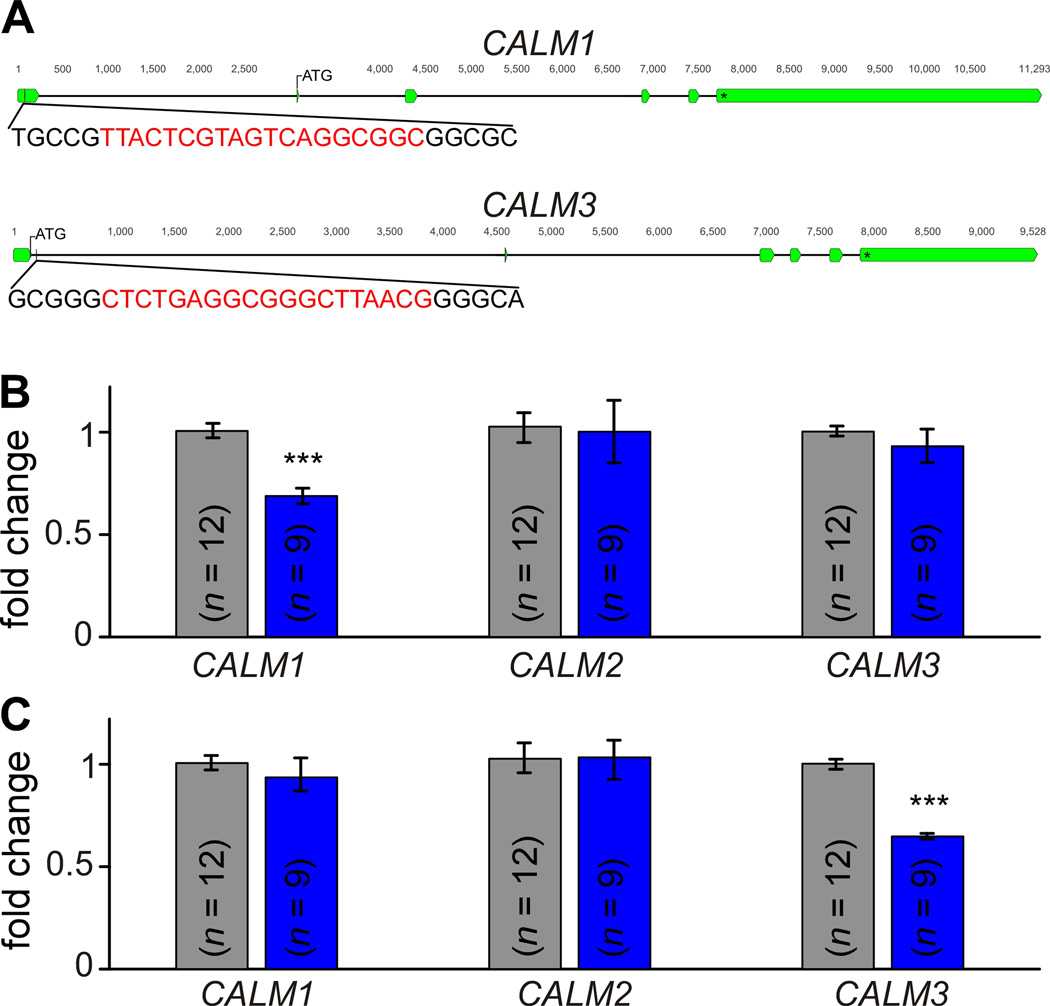

The CRISPRi technology uses a short guide RNA (gRNA) which binds specifically to a target nucleotide sequence. By pairing this gRNA with a nuclease dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to suppressor Krüppel-associated box (KRAB), selective suppression of the target gene could be achieved. Our first step was therefore to optimize gRNA sequences capable of selectively targeting CALM2. Sequence optimization was first done in silico19, followed by evaluation of the efficiency and specificity of each candidate gRNA in HEK293 cells via qPCR (Online Figure XII, Online Table II). We choose design 21 (Figure 4A) as this gRNA specifically reduced the expression of CALM2, without appreciable alteration of either CALM1 or CALM3.

Figure 4. Functional rescue of calmodulinopathy via CRISPRi treatment.

A, The genomic CALM2 gene showing the location of each exon (green). The gRNA sequence (red) is located in an intron prior to the start codon. B, QPCR results indicating mean relative mRNA levels of CALM1-3 in iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs at baseline (gray, n=5) and after CRISPRi treatment (blue, n=9). CALM2 level is significantly reduced (*** p<0.001 compared to untreated and corrected for unequal variance) with relatively unchanged levels of CALM1 and CALM3 expression (p>0.05) following the treatment. Error bars indicate ±SEM throughout. C, iPSCD130G-CaM-CM APs recorded at 0.5-Hz stimulation using ASAP1 at baseline (gray) and after CRISPRi treatment (blue). Cells correspond to the same monolayers utilized in B. APD significantly shortens following CRISPRi treatment (*** p<0.001 compared to untreated, corrected for unequal variance). Scale bar indicates change in fluorescence as measured by ΔF/F0. D, Exemplar whole cell current recordings in Ca2+ (red) and Ba2+ (black) for iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs treated with CRISPRi (left panel). Population data demonstrates a return of CDI following treatment for the Ca2+ r50 values (red) as compared to untreated cells (gray, reproduced from Figure 3I). Black shows the r50 values for treated cells in Ba2+. (n=5, * p<0.05, compared to untreated, no significant difference in variance between populations). Each biological replicate (n) is an average value of 3 technical replicates/measurements for B and C. There are no technical replicates in D.

Having identified a potential treatment strategy, we next sought to test this approach within our iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs. Monolayers were lentivirally transduced with genes encoding dCas9-mRuby-KRAB and gRNA-CFP, and expression of both constructs was confirmed by visualization of red and blue fluorescence, respectively. Compared to untreated iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs, the CRISPRi-treated iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs exhibited significantly lower levels of CALM2 mRNA with unaltered levels of CALM1 and CALM3 (Figure 4B) mRNA level with the overall reduction of total amount of CaM protein (Online Figure V). In addition, we probed the effect of treatment on multiple cardiac genes and found no significant change in the mRNA levels of CACNA1C, KCNQ1, KCNH2, SCN5A, RYR2, SERCA2, NCX1 or PLN (Online Figure IV). Having achieved a selective decrease in CALM2 transcription, we next tested if this reduction correlated with a functional effect within the iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs. Indeed, treatment of the monolayers resulted in a substantial shortening of the APDs in response to 0.5-Hz stimulation (Figure 4C, blue) as compared to untreated monolayers (gray). This effect was consistent across multiple trials, resulting in a significant decrease in APD as compared to untreated iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs (Figure 4C, right), establishing CRISPRi as a robust and promising strategy for the treatment of CaM-mediated LQTS.

Having established functional rescue of the iPSCD130G-CaM-CM monolayers, we next considered the underlying mechanism. Our previous results suggest that APD prolongation of these cells stems from a CDI deficit of the LTCC (Figure 3). We therefore predicted that successful treatment of these cells should correspond to a correction (increase) in the CDI of the LTCCs. Indeed, treated iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs displayed significantly faster CDI (Figure 4D) as compared to untreated cells. In fact, CDI in the treated cells was nearly identical to that of iPSCWT-CMs (Figure 3). Thus, CRISPRi effectively reduced the expression of the mutant and WT CALM2 alleles, resulting in normalization of the APD, and restoration of LTCC’s CDI mechanism.

Generalization of the CRISPRi strategy across calmodulinopathy subtypes

Beyond the proband described in this study, the CRISPRi treatment strategy is readily generalizable to any calmodulinopathy. In contrast to the classic CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technique where the gRNA sequence is tailored to an exact locus within the affected gene, CRISPRi targets the entire gene of interest itself, resulting in repression regardless of the specific base-pair alteration. This technique can therefore be adjusted to target CALM1 or CALM3 genes, providing efficacy across calmodulinopathy patient populations agnostic to the phenotype. We thus created gRNA sequences targeting each of the CALM genes (Figure 5A, Online Figure XII, Online Table II) and tested their efficacy in iPSC-CMs. Utilizing iPSCWT-CMs, we are indeed able to specifically decrease the expression of either CALM1 (Figure 5B) or CALM3 (Figure 5C), thus providing a modular toolkit for the treatment of calmodulinopathies resulting from a mutation within any of the three CALM genes.

Figure 5. CRISPRi can also be used to target either CALM1 or CALM3.

A, The genomic CALM1 and CALM3 genes showing location of each exon (green). The gRNA sequence (red) is located in an untranslated exon prior to the start codon of CALM1, and in an intron just past the start codon of CALM3. B, QPCR results indicating mean relative mRNA levels of CALM1-3 in iPSCWT-CMs at baseline (gray, n=12) and after treatment by CRISPRi targeting CALM1 (blue, n=9). CALM1 expression is significantly reduced (*** p<0.001 compared to untreated, no significant difference in variance between populations) with unaltered levels of CALM2 and CALM3 (p>0.05). Error bars indicate ±SEM throughout. C, QPCR results indicating mean relative mRNA levels of CALM1-3 in iPSCWT-CMs at baseline (gray) and after treatment by CRISPRi targeting CALM3 (blue, n=9). CALM3 expression level is significantly reduced (*** p<0.001 compared to untreated, no significant difference in variance between populations) with unaltered levels of CALM1 and CALM2 (p>0.05). Each biological replicate (n) is an average value of 3 technical replicates/measurements.

DISCUSSION

IPSCD130G-CaM-CMs provide a good model system for investigating the underlying pathology of LQTS-associated calmodulinopathies. Two distinct iPSCD130G-CaM-CM clones each formed a stable contracting syncytium and exhibited prolonged APs, Ca2+ cycling disturbances, and diminished LTCC CDI across extended culture. Creation of this model system enabled the generation and testing of a new therapeutic strategy. Taking advantage of the genome targeting precision of CRISPRi, we were able to selectively and efficiently silence both the WT and the D130G-containing CALM2 alleles, resulting in functional rescue of both LTCC CDI and cardiac AP morphology. This proof-of-principle therapy thus represents a first step towards a novel, targeted therapeutic design for calmodulinopathies.

Previous studies on the underlying mechanism of LQTS-associated calmodulinopathies have involved the overexpression of mutant CaM in rodent myocytes10, 11. While such studies have implicated the LTCC10 and ruled out the NaV1.5 channel11 as major contributors to the LQT phenotype of calmodulinopathy patients, they do not represent the native expression levels of mutant CaM. In particular, calmodulinopathy patients harbor a single heterozygous mutation in only one of three redundant CALM genes. The ability of the resultant small fraction of mutant CaM protein to produce the severe phenotype seen in patients has been attributed to CaM’s pre-association to the LTCC10. In this context, a fraction of LTCCs pre-bound to mutant CaM will display diminished CDI, disrupting the precise tuning of the AP by Ca2+ influx. The profound prolongation of the APs and decreased CDI observed in the iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs corroborate just such a dominant negative effect. Moreover, the amelioration of the LQTS phenotype of the iPSCD130G-CaM-CMs via suppression of CALM2 transcription firmly establishes this mutation as the causative genetic mechanism. However, this new mechanistic insight also presents a significant challenge to the treatment of these calmodulinopathy patients. The pre-association of LTCCs with both mutant and WT CaM makes selective targeting of the disrupted LTCCs nearly impossible. Thus, any treatment option for these patients must selectively target the mutant CaM, prior to cytosolic expression and binding to the LTCC.

Fortunately, CRISPRi provides just such a therapeutic option. In fact, recent work demonstrates that CRISPRi is capable of robust gene knock down within both iPSCs as well as iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes, making this a highly attractive method which has already been validated for our model system. Moreover, this technique offers the advantages of selectivity, reversibility, and generalizability13–15. That is, RNA transcription of specific mutation-containing CALM genes can be repressed, without modifying the patient genome and risking permanent alteration of off-target or downstream elements13, 14. Further, this technique is generalizable to any calmodulinopathy. Here, we present a simple therapeutic toolbox in which three gRNAs targeting either CALM1, CALM2, or CALM3 can be chosen to match any calmodulinopathy patient. Importantly, this means that while this study focused on the LQTS-associated calmodulinopathies, the therapy developed here should also be effective for the CPVT- and IVF-associated calmodulinopathies. Moreover, as expected due to the widespread distribution of CaM, calmodulinopathy patients also exhibit extra-cardiac phenotypes including seizures and developmental delays2. Importantly, the CRISPRi toolkit should be effective on these non-cardiac symptoms, as targeting of the CRISPRi can be adjusted to include any affected organ systems.

More broadly, this therapeutic principle could be applied to the treatment of any disease in which there is a redundancy of the affected gene. Thus, the CRISPRi strategy described here not only represents a promising new treatment option for calmodulinopathy patients, but could provide a generalizable strategy in the treatment of a variety of diseases. Fortuitously, development of CRISPR/Cas9 delivery into patients is already well underway34, propelling the translation of these findings towards improving patients’ health and quality of life and in the case of patients with a LQTS/CPVT/IVF-associated calmodulinopathy, preventing sudden death in the young.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is Known?

Calmodulinopathies comprise a new category of life-threatening genetic cardiac arrhythmias caused by single heterozygous point mutations within the calcium sensor calmodulin (CaM).

Calmodulinopathy mutations alter the Ca2+ binding affinity of CaM, implicating numerous Ca2+/CaM binding partners as potential pathogenic elements, including the L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC), which exhibits disrupted feedback regulation in the presence of mutant CaM when studied in a heterologous expression system.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

This study develops a robust model system using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from a calmodulinopathy patient, which recapitulates the phenotype of the patients and provides a test bed for mechanistic understanding and therapeutic design.

A mechanistic link between defective Ca2+ regulation of LTCC and the calmodulinopathy phenotype is established.

A therapeutic strategy based on CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) demonstrates restoration of the action potential in the calmodulinopathy iPSC cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs).

Calmodulinopathies represent a growing class of severe cardiac arrhythmias, which are often resistant to conventional treatments. This disorder is associated with mutations that disrupt Ca2+ binding to CaM, a ubiquitous Ca2+ sensor molecule vital to heart and skeletal muscle contraction, memory, and immunological responses. Here, we utilize iPSC-CMs derived from a recently identified calmodulinopathy patient with severe long QT syndrome (LQTS) to create a model system suitable for examining calmodulinopathy pathogenesis and designing therapeutic interventions. Using this model system, we demonstrate a significant impact of the calmodulinopathy mutations on the Ca2+ regulation of LTCCs, establishing this channel as a major causative factor of the LQTS phenotype. Further, application of CRISPRi robustly suppresses the expression of the mutant CaM gene, and produces a functional rescue of the calmodulinopathy phenotype, as evidenced by the restoration of the cardiac action potential morphology and LTCC function. This therapeutic strategy is generalizable to any calmodulinopathy mutation, thus it holds great promise for improving the health and quality of life of many calmodulinopathy patients

Acknowledgments

David T. Yue passed away on December 23, 2014. His mentorship, wisdom, and kindness are greatly missed.

We thank Drs. Zhaohui Ye and Linchao Cheng for help in conducting teratoma formation assay, Dr. Stephen Eacker, for his insight in optimizing the delivery of CRISPR into iPSCs, and Dr. Peter Anderson for assistance with flow cytometry. We also thank Dr. Leslie Tung for providing valuable advice and discussions, and members of the Calcium Signals Lab for ongoing feedback.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship (W.B.L.), R01MH065531 (W.B.L., I.E.D.), The Magic that Matters Fund and The Zegar Family Foundation (D.D., G.F.T.). Mayo Clinic Windland Smith Rice Comprehensive Sudden Cardiac Death Program (M.J.A.)

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CaM

calmodulin

- LQTS

long QT syndrome

- CPVT

catecholaminergic polymorphic tachycardia

- IVF

idiopathic ventricular fibrillation

- LTCC

L-type Ca2+ channel

- CDI

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent inactivation

- AP(D)

action potential (duration)

- iPSC(-CM)

induced pluripotent stem cell(-derived cardiomyocyte)

- CRISPRi

CRISPR interference

- CaT

Ca2+ transients

- VDI

voltage-dependent inactivation

- gRNA

guide RNA

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

D.J.T.: Transgenomic (royalties); M.J.A: Boston Scientific, Gilead Sciences, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical (consultant), Transgenomic (royalties). The rest of the authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boczek NJ, Gomez-Hurtado N, Ye D, Calvert ML, Tester DJ, Kryshtal D, Hwang HS, Johnson CN, Chazin WJ, Loporcaro CG, Shah M, Papez AL, Lau YR, Kanter R, Knollmann BC, Ackerman MJ. Spectrum and prevalence of calm1-, calm2-, and calm3-encoded calmodulin (cam) variants in long qt syndrome (lqts) and functional characterization of a novel lqts-associated cam missense variant, e141g. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2016 doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crotti L, Johnson CN, Graf E, De Ferrari GM, Cuneo BF, Ovadia M, Papagiannis J, Feldkamp MD, Rathi SG, Kunic JD, Pedrazzini M, Wieland T, Lichtner P, Beckmann BM, Clark T, Shaffer C, Benson DW, Kaab S, Meitinger T, Strom TM, Chazin WJ, Schwartz PJ, George AL., Jr Calmodulin mutations associated with recurrent cardiac arrest in infants. Circulation. 2013;127:1009–1017. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.001216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makita N, Yagihara N, Crotti L, Johnson CN, Beckmann BM, Roh MS, Shigemizu D, Lichtner P, Ishikawa T, Aiba T, Homfray T, Behr ER, Klug D, Denjoy I, Mastantuono E, Theisen D, Tsunoda T, Satake W, Toda T, Nakagawa H, Tsuji Y, Tsuchiya T, Yamamoto H, Miyamoto Y, Endo N, Kimura A, Ozaki K, Motomura H, Suda K, Tanaka T, Schwartz PJ, Meitinger T, Kaab S, Guicheney P, Shimizu W, Bhuiyan ZA, Watanabe H, Chazin WJ, George AL., Jr Novel calmodulin mutations associated with congenital arrhythmia susceptibility. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2014;7:466–474. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reed GJ, Boczek NJ, Etheridge S, Ackerman MJ. Calm3 mutation associated with long qt syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nyegaard M, Overgaard MT, Sondergaard MT, Vranas M, Behr ER, Hildebrandt LL, Lund J, Hedley PL, Camm AJ, Wettrell G, Fosdal I, Christiansen M, Borglum AD. Mutations in calmodulin cause ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;91:703–712. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marsman RF, Barc J, Beekman L, Alders M, Dooijes D, van den Wijngaard A, Ratbi I, Sefiani A, Bhuiyan ZA, Wilde AA, Bezzina CR. A mutation in calm1 encoding calmodulin in familial idiopathic ventricular fibrillation in childhood and adolescence. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boczek NJ, Ye D, Jin F, Tester DJ, Huseby A, Bos JM, Johnson AJ, Kanter R, Ackerman MJ. Identification and functional characterization of a novel cacna1c-mediated cardiac disorder characterized by prolonged qt intervals with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, congenital heart defects, and sudden cardiac death. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:1122–1132. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.002745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dick IE, Joshi-Mukherjee R, Yang W, Yue DT. Arrhythmogenesis in timothy syndrome is associated with defects in ca(2+)-dependent inactivation. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10370. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukuyama M, Wang Q, Kato K, Ohno S, Ding WG, Toyoda F, Itoh H, Kimura H, Makiyama T, Ito M, Matsuura H, Horie M. Long qt syndrome type 8: Novel cacna1c mutations causing qt prolongation and variant phenotypes. Europace. 2014;16:1828–1837. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Limpitikul WB, Dick IE, Joshi-Mukherjee R, Overgaard MT, George AL, Jr, Yue DT. Calmodulin mutations associated with long qt syndrome prevent inactivation of cardiac l-type ca(2+) currents and promote proarrhythmic behavior in ventricular myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014;74:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin G, Hassan F, Haroun AR, Murphy LL, Crotti L, Schwartz PJ, George AL, Satin J. Arrhythmogenic calmodulin mutations disrupt intracellular cardiomyocyte ca2+ regulation by distinct mechanisms. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000996. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erickson MG, Alseikhan BA, Peterson BZ, Yue DT. Preassociation of calmodulin with voltage-gated ca(2+) channels revealed by fret in single living cells. Neuron. 2001;31:973–985. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00438-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilbert LA, Larson MH, Morsut L, Liu Z, Brar GA, Torres SE, Stern-Ginossar N, Brandman O, Whitehead EH, Doudna JA, Lim WA, Weissman JS, Qi LS. Crispr-mediated modular rna-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell. 2013;154:442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qi LS, Larson MH, Gilbert LA, Doudna JA, Weissman JS, Arkin AP, Lim WA. Repurposing crispr as an rna-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell. 2013;152:1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandegar MA, Huebsch N, Frolov EB, Shin E, Truong A, Olvera MP, Chan AH, Miyaoka Y, Holmes K, Spencer CI, Judge LM, Gordon DE, Eskildsen TV, Villalta JE, Horlbeck MA, Gilbert LA, Krogan NJ, Sheikh SP, Weissman JS, Qi LS, So PL, Conklin BR. Crispr interference efficiently induces specific and reversible gene silencing in human ipscs. Cell stem cell. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spencer CI, Baba S, Nakamura K, Hua EA, Sears MA, Fu CC, Zhang J, Balijepalli S, Tomoda K, Hayashi Y, Lizarraga P, Wojciak J, Scheinman MM, Aalto-Setala K, Makielski JC, January CT, Healy KE, Kamp TJ, Yamanaka S, Conklin BR. Calcium transients closely reflect prolonged action potentials in ipsc models of inherited cardiac arrhythmia. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;3:269–281. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakahama H, Di Pasquale E. Generation of cardiomyocytes from pluripotent stem cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016;1353:181–190. doi: 10.1007/7651_2014_173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapoor A, Sekar RB, Hansen NF, Fox-Talbot K, Morley M, Pihur V, Chatterjee S, Brandimarto J, Moravec CS, Pulit SL, Consortium QTI-IG, Pfeufer A, Mullikin J, Ross M, Green ED, Bentley D, Newton-Cheh C, Boerwinkle E, Tomaselli GF, Cappola TP, Arking DE, Halushka MK, Chakravarti A. An enhancer polymorphism at the cardiomyocyte intercalated disc protein nos1ap locus is a major regulator of the qt interval. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;94:854–869. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heigwer F, Kerr G, Boutros M. E-crisp: Fast crispr target site identification. Nat Methods. 2014;11:122–123. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.St-Pierre F, Marshall JD, Yang Y, Gong Y, Schnitzer MJ, Lin MZ. High-fidelity optical reporting of neuronal electrical activity with an ultrafast fluorescent voltage sensor. Nat. Neurosci. 2014;17:884–889. doi: 10.1038/nn.3709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, Schreiter ER, Kerr RA, Orger MB, Jayaraman V, Looger LL, Svoboda K, Kim DS. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parker RA, Berman NG. Sample size. The American Statistician. 2003;57:166–170. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma A, Wu JC, Wu SM. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes for cardiovascular disease modeling and drug screening. Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 2013;4:150. doi: 10.1186/scrt380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma J, Guo L, Fiene SJ, Anson BD, Thomson JA, Kamp TJ, Kolaja KL, Swanson BJ, January CT. High purity human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: Electrophysiological properties of action potentials and ionic currents. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011;301:H2006–H2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00694.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marban E. Cardiac channelopathies. Nature. 2002;415:213–218. doi: 10.1038/415213a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie LH, Weiss JN. Arrhythmogenic consequences of intracellular calcium waves. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009;297:H997–H1002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00390.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hwang HS, Kryshtal DO, Feaster TK, Sanchez-Freire V, Zhang J, Kamp TJ, Hong CC, Wu JC, Knollmann BC. Comparable calcium handling of human ipsc-derived cardiomyocytes generated by multiple laboratories. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2015;85:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Splawski I, Timothy KW, Decher N, Kumar P, Sachse FB, Beggs AH, Sanguinetti MC, Keating MT. Severe arrhythmia disorder caused by cardiac l-type calcium channel mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:8089–8096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502506102. discussion 8086-8088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Splawski I, Timothy KW, Sharpe LM, Decher N, Kumar P, Bloise R, Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ, Joseph RM, Condouris K, Tager-Flusberg H, Priori SG, Sanguinetti MC, Keating MT. Ca(v)1.2 calcium channel dysfunction causes a multisystem disorder including arrhythmia and autism. Cell. 2004;119:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Livshitz LM, Rudy Y. Regulation of ca2+ and electrical alternans in cardiac myocytes: Role of camkii and repolarizing currents. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;292:H2854–H2866. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01347.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo CH, Rudy Y. A dynamic model of the cardiac ventricular action potential. I. Simulations of ionic currents and concentration changes. Circ. Res. 1994;74:1071–1096. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.6.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo CH, Rudy Y. A dynamic model of the cardiac ventricular action potential. Ii. Afterdepolarizations, triggered activity, and potentiation. Circ. Res. 1994;74:1097–1113. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.6.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petryszak R, Burdett T, Fiorelli B, Fonseca NA, Gonzalez-Porta M, Hastings E, Huber W, Jupp S, Keays M, Kryvych N, McMurry J, Marioni JC, Malone J, Megy K, Rustici G, Tang AY, Taubert J, Williams E, Mannion O, Parkinson HE, Brazma A. Expression atlas update--a database of gene and transcript expression from microarray- and sequencing-based functional genomics experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D926–D932. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ran FA, Cong L, Yan WX, Scott DA, Gootenberg JS, Kriz AJ, Zetsche B, Shalem O, Wu X, Makarova KS, Koonin EV, Sharp PA, Zhang F. In vivo genome editing using staphylococcus aureus cas9. Nature. 2015;520:186–191. doi: 10.1038/nature14299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.