Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) remain primary therapeutic targets for numerous cardiovascular disorders, including heart failure (HF), due to their influence on cardiac remodeling in response to elevated neurohormone signaling. GPCR blockers have proven to be beneficial in the treatment of HF by reducing chronic G protein activation and cardiac remodeling, thereby extending the lifespan of HF patients. Unfortunately this effect does not persist indefinitely, thus next generation therapeutics aim to selectively block harmful GPCR-mediated pathways while simultaneously promoting beneficial signaling. Transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) has been shown to be mediated by an expanding repertoire of GPCRs in the heart, and promotes cardiomyocyte survival, thus may offer a new avenue of HF therapeutics. However, GPCR-dependent EGFR transactivation has also been shown to regulate cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis by different GPCRs, and via distinct molecular mechanisms. Here, we discuss the mechanisms and impact of GPCR-mediated EGFR transactivation in the heart, focusing on angiotensin II, urotensin II and β-adrenergic receptor systems, and highlight areas of research that will help us to determine whether this pathway can be engaged as future therapeutic strategy.

Keywords: G protein-coupled receptor, epidermal growth factor receptor, cardiac remodeling

Introduction

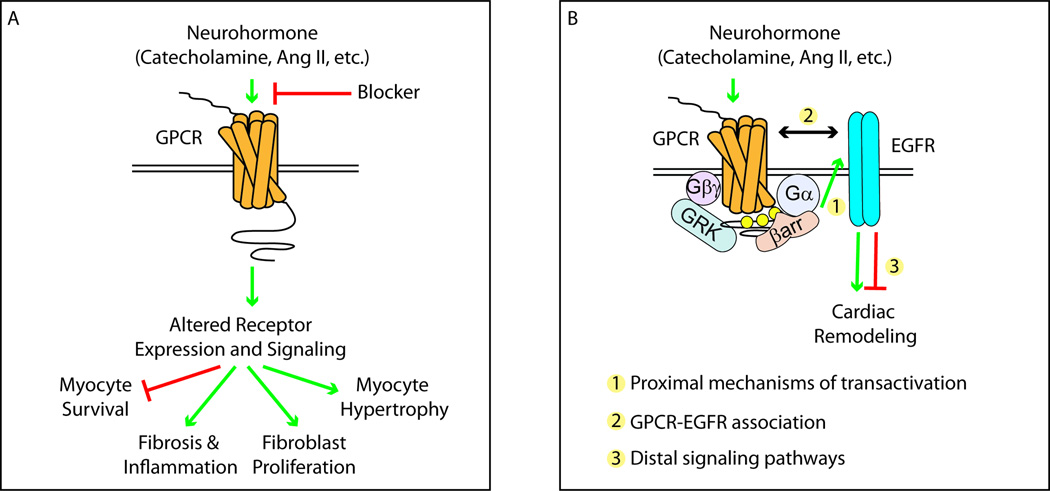

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are a large family of 7 transmembrane-spanning proteins that mediate responses to a diverse array of external stimuli including hormones, neurotransmitters, odorants and photons. GPCRs are known to play a role in the development of cardiovascular disorders such as hypertension and heart failure, and therapeutics that target GPCRs constitute ~40% of currently used drugs, demonstrating their continued importance as pharmacological targets. Stimulation of GPCRs initiates a number of signaling pathways to regulate extensive cellular responses, which in the heart includes contractility, hypertrophy, proliferation, survival and fibrosis (Figure 1A)1–4. While the proximal mechanisms relaying GPCR signals are now commonly recognized to include engagement of G protein- and/or GPCR kinase (GRK)/β-arrestin (βarr)-dependent pathways4, the distal mechanisms that regulate cardiac cell behavior are divergent and vary by cell type and pathophysiologic status. Understanding how these mechanisms regulate cardiac remodeling during disease progression remains a fundamental goal of cardiac GPCR research and development of therapeutics. One such mechanism that has been shown to modulate various aspects of cardiac remodeling downstream of GPCRs is via transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR).

Figure 1. The influence of GPCR-mediated EGFR transactivation on cardiac remodeling processes.

A) Prolonged neurohormone stimulation of cardiac-expressed GPCRs leads to changes in cardiac remodeling, including myocyte survival and hypertrophy, fibroblast proliferation, fibrosis and inflammation. Blockers of these GPCR systems are commonly used to decrease cardiac remodeling during conditions such as heart failure. B) GPCR-mediated EGFR transactivation influences numerous cardiac remodeling processes and may occur via mechanisms including either G protein- or GRK/βarr-dependent signaling in a GPCR- and cell-type-specific manner. Research areas requiring further development include: 1) the proximal mechanism of EGFR transactivation by specific GPCRs, 2) the mechanism and contribution of GPCR-EGFR association in mediating transactivation-dependent outcomes and 3) the distal signaling pathways unique to specific GPCR-EGFR complexes that may influence cardiac remodeling.

EGFR is a receptor tyrosine kinase, of which there are four closely related members: EGFR (ErbB-1, HER1), HER2 (ErbB2/neu), HER3 (ErbB3) and HER4 (ErbB4). While ErbB2-4 are beginning to be studied more frequently for their potential roles in the regulation of cardiomyocyte proliferation and cardiotoxicities related to cancer therapeutics5–8, EGFR is the most well-characterized family member in the heart. Several endogenous ligands, including epidermal growth factor (EGF), heparin binding-EGF (HB-EGF) and transforming growth factor α (TGFα)9, 10, bind EGFR to induce dimerization or stabilization of an existing dimer and allow trans-phosphorylation of C-terminal tyrosine residues by the kinase domain, thereby engaging various signal transduction pathways11.

EGFR was first shown to be activated by GPCRs 20 years ago when Ullrich’s group reported that EGFR phosphorylation increased following treatment with several GPCR agonists including endothelin and thrombin, which could be blocked using an EGFR inhibitor or dominant-negative mutant EGFR12. Since the initial discovery of GPCR-dependent EGFR transactivation, an increasing number of GPCRs have been identified as being capable of transactivating EGFR, including adenosine13, 14, adrenergic15–20, aldosterone21, angiotensin II22–25, bradykinin26, δ-opioid27, endothein-128, 29, muscarinic30, prostaglandin E231, protease-activated32, 33, sphingosine-1-phosphate34 and urotensin II35–37 receptors. A growing body of evidence demonstrates that GPCR-mediated EGFR transactivation occurs in the heart, playing potentially important roles in both normal physiology as well as pathophysiology.

Mechanisms of GPCR-mediated EGFR transactivation and association

With regard to the EGFR transactivation process, there are several molecular mechanisms that comprise the means by which GPCR stimulation may lead to EGFR-dependent signaling, often occurring in both GPCR- and cell-specific manners, via either intracellular or extracellular pathways, as previously reviewed38. Briefly, GPCR stimulation rapidly leads to both G protein-dependent and GRK/βarr-dependent signaling responses, either of which may lead to EGFR transactivation. Several GPCRs induce EGFR activation via matrix metalloprotease (MMP)- or a disintegrin and metalloprotease (ADAM)-mediated cleavage of extracellular EGFR ligand, often HB-EGF, which can be induced in either a G protein- or GRK/βarr-dependent manner. While this process typically involves intermediate signaling adapters or kinases such as Src, it was recently shown that Gβγ subunits can directly activate MMP14 via to induce HB-EGF cleavage and EGFR transactivation in cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts25. Thus, in a GPCR- and cell type-specific manner, EGFR transactivation may be engaged via multiple mechanisms (Figure 1B).

In addition to intermediate signaling components, some GPCRs structurally interact with EGFR in absence of receptor ligands which may enhance the efficiency of EGFR transactivation or focus the downstream signaling response to particular subcellular locales39–41. Such multireceptor complexes may form on membrane microdomains, since blockage of lipid rafts has been demonstrated to disrupt a specific interaction between EGFR and the bile acid receptor TGR542. This may be an especially important concept with respect to fully differentiated adult cardiomyocytes that are known to have sarcolemmal microdomains containing various GPCRs43, some of which, like β2AR, have been well-established to both interact with and transactivate EGFR39, 44. Aside from membrane localization, modulation of GPCR activity may influence the stability of their interaction with EGFR, as stimulation of β2AR with the full agonist isoproterenol (ISO) increased, while treatment with the inverse agonist ICI 188,551 reciprocally decreased, its association with EGFR39. Interestingly, not all GPCR-EGFR complexes respond to their ligands in the same manner since β1AR-EGFR interaction did not increase following stimulation with ISO, but dissociated in response to EGF40, while stimulation of an AT1R-EGFR complex with either AngII or EGF increased its association in a temporal manner41.

The impact of receptor ligands on modulation of GPCR-EGFR interaction appears to be dependent on the GPCR-EGFR complex in particular and may suggest different mechanisms of both basal and post-stimulation association with EGFR. While βarr-dependent signaling has been implicated in maintaining or increasing βAR association with EGFR following catecholamine stimulation39, 40, less is known about the actual structural requirements at the receptor level that allow for EGFR association. With regard to β1AR, it was shown that mutation of all the putative C-terminal GRK phosphorylation sites almost completely abolished its ability to interact with EGFR, even in under non-stimulated conditions40. Whether this was due to a GRK-specific effect or occurred as a by-product of a structural change in the C-terminus of β1AR is not known, although another study showed that the third intracellular loop and a portion of the C-terminus of AT2R was required for interaction with ErbB345. Similarly, current knowledge regarding the specific region of EGFR that is responsible for GPCR interaction is lacking. However, it has been reported that the juxtamembrane domain of EGFR binds Gs protein and that an increase in Gs activity disrupts this interaction46, thus the juxtamembrane domain of EGFR could serves as a point of association with Gs protein-coupled receptors.

Following ligand binding and EGFR dimerization, C-terminal trans-phosphoryation leads to adapter protein recruitment and formation of signaling networks47. EGFR has numerous tyrosine phosphorylation sites in its C-terminus and distinct phosphorylation patterns may occur in response to differential activation by various GPCRs, which could result in the recruitment of unique sets of adaptor proteins48. This concept is similar to the “Barcode Hypothesis” for GPCRs where distinct phosphorylation patterns, or barcodes, on the C-terminal tail of GPCRs have been shown to produce differences in adapter protein recruitment49–52. While differential EGFR phosphorylation patterns have been observed in response to EGF stimulation in distinct cell lines47, the impact of transactivation by various GPCRs on EGFR phosphorylation patterns has not been extensively investigated. Indeed, a majority of studies have reported the impact of GPCR-mediated transactivation on phosphorylation of a limited number of tyrosine residues in the C-terminus of EGFR. However, unique GPCR-mediated EGFR phosphorylation patterns could contribute to divergent adapter protein recruitment, network formation and downstream signaling responses produced in different cardiac cell types in response to different ligands, processes that await discovery.

Impact and implications of GPCR-dependent EGFR transactivation

An expanding cohort of GPCRs (as listed above) has been shown to influence cardiac remodeling, including hypertrophy, fibrosis and survival, through the transactivation of EGFR. Here, we focus our discussion on three GPCR systems (AT1R, UTIIR and βAR) with distinct G protein-coupling characteristics and how they may engage EGFR to elicit changes in cardiac remodeling processes.

Angiotensin Type 1A Receptor (AT1R)

Angiotensin II (AngII), acting through AT1R, has been demonstrated to relay both pro-hypertrophic and pro-fibrotic effects via EGFR transactivation in the heart. For instance, AngII infusion-induced pathological cardiac remodeling in vivo was shown by several groups to be largely abrogated by EGFR inhibition, either via siRNA targeting EGFR53, co-infusion with the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib54 or overexpression of inhibitors of EGFR signaling, including receptor-associated late transducer (RALT)55 and a dominant-negative EGFR mutation56. At a cellular level, AT1R enhances both cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and cardiac fibroblast proliferation. AT1R-mediated EGFR transactivation-sensitive neonatal cardiomyocyte hypertrophy was initially demonstrated to require Gαq protein activation, MMP activation and downstream ERK signaling24, but was insensitive to PKC inhibition. Similarly, AngII treatment of cardiac fibroblasts was demonstrated to enhance EGFR phosphorylation and downstream ERK activation, leading led to increased cfos expression and DNA synthesis, in a PKC-independent manner22. Instead, these responses were sensitive to treatment with either the EGFR inhibitor AG 1478, a dominant-negative EGFR mutant, a Ca2+ chelator or Ca2+/calmodulin kinase inhibitors. Further, DNA synthesis was unaffected by the addition of an anti-EGF antibody to the culture media and conditioned media taken from AngII-treated cells, suggesting an intracellular activation mechanism.

While the distal responses to AT1R-mediated EGFR transactivation appear to commonly involve ERK activation, the proximal mechanism(s) linking AT1R stimulation to EGFR transactivation-mediated effects on these processes are varied and somewhat controversial. While AT1R couples to both Gq/11 and G12/13 protein families4, Gq protein-mediated AT1R signaling was initially associated with EGFR transactivation-dependent effects on cardiac remodeling, although Gq protein-independent signaling via phosphorylation of AT1R at Tyr319 was later shown to contribute to remodeling processes. It was postulated that Tyr319 allowed binding with SHP2 to mediate interaction with and transactivation of EGFR and an AT1R-Y319F mutant no longer induced cardiac fibroblast proliferation57. In fact, transgenic mice overexpressing AT1R-Y319F did not develop cardiac hypertrophy, in contrast to mice overexpressing WT-AT1R, and were resistant to AngII infusion-induced hypertrophy, cardiomyocyte apoptosis and fibrosis, similar to mice overexpressing a dominant negative EGFR23. Additionally, PKC, STAT3, ERK, Akt and Gαq activation were unaltered in Tg-Y319F mice compared to Tg-WT, suggesting that these pathways are not involved in the adverse effects of AngII treatment. However, more recent work has again highlighted the importance of AT1R-Gq protein-dependent EGFR transactivation in mediating cardiomyocyte hypertrophy58, independent of Tyr319, and an elegant screening study identified numerous kinases that are likely be involved in transmitting AT1R stimulation to EGFR transactivation, confirming roles for triple functional domain/PTPRF interacting (TRIO), bone marrow kinase in chromosome X (BMX) and choline kinase α (CHKA) in the process59. BMX, a non-receptor tyrosine kinase, was subsequently shown to be involved in AngII-mediated cardiac hypertrophy, though the impact of BMX on EGFR transactivation was not specifically investigated in this study60. Thus, the role these newer targets play in AT1R-dependent EGFR transactivation-induced cardiac hypertrophy or fibrosis remains to be directly tested.

Urotensin II receptor (UTIIR)

Stimulation of UTIIR, upregulated during congestive heart failure in human hearts61, also leads to EGFR transactivation in both in vitro and in vivo models. Urotensin II (UII) treatment has also been shown to engage EGFR transactivation in neonatal cardiomyocytes, independent of PKC, PI3K or Ca2+ mobilization, leading to increased ERK and p38 activity and resulting in hypertrophy36. This effect on cardiomyocyte hypertrophy has also been shown to involve the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which oxidize and inhibit the activity of the phosphotyrosine phosphatase SHP-2, thus increasing EGFR activation37. UII-induced ROS generation was also shown to relay EGFR transactivation in cardiac fibroblasts, leading to enhanced ERK activation and proliferation62. Like AT1R, UTIIR also couples to Gq protein to exert many of its effects63, however it has also been demonstrated to signal via Gi protein, though an essential role for either G protein in relaying EGFR transactivation has not been defined. Indeed, G protein-independent signaling may be more crucial for UII-induced EGFR transactivation since UII treatment of HEK 293 cells initiated βarr-dependent EGFR transactivation and internalization, which was essential for relaying a decrease in cell death35. Regardless of the proximal mechanisms involved, blocking UTIIR using the UTII antagonist urantide in a mouse model of pressure overload (transaortic constriction, TAC) was shown to worsen cardiac function, fibrosis and cell death outcomes, changes associated with decreased EGFR and ERK phosphorylation35. Thus, the cardiac urotensin II-EGFR signaling system may represent an as-yet untapped therapeutic target for HF drug development.

β-Adrenergic Receptors (βAR)

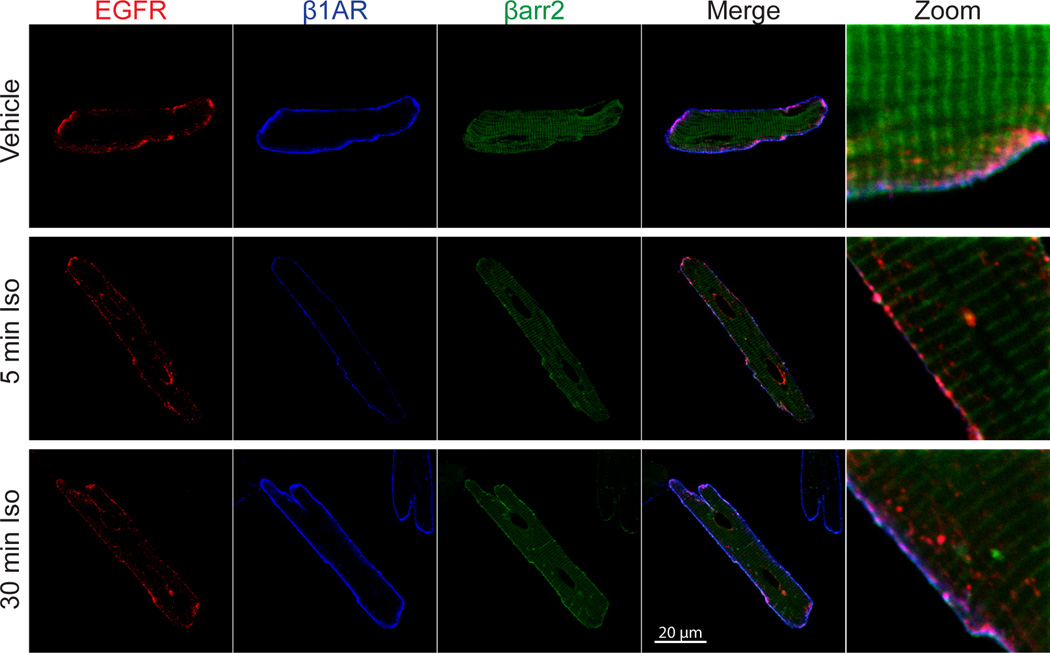

Both β1AR and β2AR have been shown to interact with EGFR and mediate its transactivation using a similar molecular mechanism. Both βAR isoforms rely on G protein-independent, GRK/βarr-dependent signaling to promote Src- and MMP-mediated HB-EGF shedding and subsequent EGFR activation15, 16, 39, 64. In addition, PI3K-dependent Src activation is required for β2AR-mediated EGFR transactivation and significantly increases their association in a multi-receptor complex44. While the β1AR-EGFR complex does not appear to be enhanced upon β1AR stimulation, GRK-βarr-dependent signaling is required to maintain their association in HEK 293 cells40. β1AR-EGFR association also occurs in human heart40 and adult feline ventricular cardiomyocytes (AFVM, Figure 2), however the kinetics of complex association following β1AR stimulation appears to differ among different model systems. While β1AR-EGFR association can be observed for prolonged timepoints after treatment with isoproterenol (ISO) in HEK 293 cells40, activation of β1AR in AFVM results in rapid co-localization with internalized EGFR and βarr2, but at longer timepoints is largely recycled back to the sarcolemmal membrane while EGFR undergoes prolonged internalization, including perinuclear localization (Figure 2).

Figure 2. EGFR co-localization with β1AR and βarr2 following catecholamine stimulation in adult cardiomyocytes.

Adult feline ventricular myocytes (AFVM) were infected with adenoviral constructs for EGFR-mCFP (MOI of 50), Flag-β1AR (MOI 200) and βarr2-mYFP (MOI of 200) and plated on laminin (40 µg/mL)-coated coverslips. Forty-eight hours following plating, cells were treated with isoproterenol (ISO, 10µM) for 0, 5 or 30 min, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton-X 100. Cells were blocked in 0.1% BSA followed by incubation with an EGFR antibody (Millipore clone LA22; 1:100) with an AlexaFluor 568-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000) and a Flag M2 antibody (Sigma Aldrich; 1:1000) with an AlexaFluor 350-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000). ISO stimulation produced a rapid (5 min) co-localization of EGFR (red), β1AR (blue) and βarr2 (green) primarily at the sarcolemma of adult feline ventricular myocytes (AFVM), with EGFR internalization and perinuclear localization also evident. At a later timepoint (30 min), β1AR and βarr2 remain largely co-localized at the sarcolemma, whereas prolonged EGFR internalization and perinuclear localization is observed. Abbreviations: mCFP (monomeric cyan fluorescent protein), mYFP (monomeric yellow fluorescent protein).

As with other GPCRs, ERK activity is increased distal to β1AR-dependent EGFR transactivation and, along with enhanced Akt activation, this mechanism promotes cardiomyocyte survival16, 18, 65, while in cardiac fibroblasts, β2AR-mediated transactivation leads to increased DNA synthesis and mitogenesis15. An initial investigation of the subcellular localization of signaling in response to β1AR-mediated EGFR transactivation were performed in HEK293 cells and showed that activated ERK was restricted to the cytosolic compartment, with no nuclear accumulation observed even after 60 minutes of stimulation40. In contrast, direct EGFR stimulation with either EGF or HB-EGF induced rapid nuclear accumulation of ERK, within 5 minutes, that persisted for 60 minutes and resulted in the activation of the transcription factor Elk-1, suggesting that β1AR-mediated EGFR transactivation provides a mechanism to restrict EGFR signaling to cytosolic processes. However, subsequent studies in primary neonatal rat cardiomyocytes and in whole mouse hearts demonstrated that βAR-mediated EGFR transactivation actually resulted in nuclear accumulation of activated ERK, as well as Akt18. Further, our group discovered a role for EGFR transactivation-dependent repression of TRAIL, a pro-apoptotic factor whose decreased expression promoted cardiomyocyte survival18. Subsequently, we detailed both the acute and chronic transcriptome responses to βAR-mediated EGFR transactivation in the mouse heart, with foci on apoptotic genes and cytokines, including thrombospondin 1, Ccl2 and TNFα66, 67. Coupled with perinuclear localization of EGFR following β1AR stimulation observed in AFVM (Figure 2), our cumulative studies suggest that in relevant primary cardiomyocyte and whole heart systems, βAR-mediated EGFR transactivation influences survival, hypertrophy and fibrosis via dynamic regulation of the transcriptome18, 66, 67.

In vivo studies to date do indeed demonstrate that chronic catecholamine stimulation leads to increased cardiac cell death, fibrosis and hypertrophy with decreased function, all of which are sensitive to EGFR inhibition. However, use of different EGFR inhibitors in vivo resulted in different outcomes, wherein erlotinib worsened cardiac dilation, decreased cardiac function and increased cell death in response to chronic ISO infusion16, while gefitinib reduced ISO-induced cardiac dysfunction, hypertrophy and cell death, but increased fibrosis on its own67. These disparate results could arise from EGFR-independent, off-target effects since gefitinib and erlotinib each interact with a wide array of kinases75. For instance, Fabian et al. demonstrated that gefitinib binds to at least 18 kinases and erlotinib to 23, with only 12 of these kinases shown to commonly bind to both75. Such off-target effects could explain differences in βAR-mediated cardiac remodeling responses in the presence of an EGFR inhibitor and provide caution for in vivo pharmacologic studies. Thus, more refined in vivo models, preferably genetic and cell type-specific, are essential to better understand the impact of βAR-mediated EGFR transactivation in the heart.

Although βAR-mediated EGFR transactivation shows promise as a cardioprotective pathway, it has been difficult to characterize. A major hurdle to defining its impact in cardiomyocytes has been the reliance upon loss-of-function analyses using EGFR inhibitors in the presence of an unbiased βAR agonist. While suggestive of the impact of this pathway on processes such as survival, EGFR inhibitors do not directly measure the contribution of EGFR transactivation in the absence of G protein-dependent βAR signaling. The orthosteric non-selective β-blocker carvedilol has been shown to induce βarr-biased βAR-mediated signaling, including EGFR transactivation68–70; however, these studies were performed either in HEK 293 cell systems with exogenous receptor expression or in whole heart using a very high dose of carvedilol with no functional insight at a contractile level. Indeed, it has recently been demonstrated that carvedilol does not enhance cardiomyocyte contractility64, likely due to its inverse agonist properties71. Further, a recent meta-analysis revealed a lack of clinical difference between carvedilol versus the unbiased β-blocker metoprolol succinate in HF patients72. Taken together, these data indicate that although carvedilol may have the capacity to induce βarr-biased βAR signaling and EGFR transactivation, it likely does not occur at therapeutically relevant doses, and if doses were increased to achieve such biased signaling, it may be at the expense of cardiac contractility. Future advancements in understanding both the molecular mechanisms and functional outcomes of βAR-mediated EGFR transactivation in cardiac cells and the whole heart are therefore likely to stem from next generation biased βAR ligands that can selectively activate the EGFR pathway.

Conclusion

An ongoing question in the field is how a single receptor, EGFR, can produce distinct effects and physiological outcomes depending on its mode of activation. Acting as a nodal input for numerous GPCRs, EGFR has the potential to fine-tune neurohormone signals both physiologically and pathologically. From in vitro cell model studies, various mechanisms of transactivation have been identified that can be engaged by distinct receptor systems, however how it is all put together in meaningful way in fully differentiated cardiomyocytes, or more generally in the whole heart in vivo is not well understood. Dynamic subcellular distribution of EGFR with various GPCRs and proximal regulators likely plays a role in the integration of such signals, but there have been major barriers to studying EGFR-sensitive cardiac GPCR signaling effects in vivo. EGFR KO mice are embryonic lethal, and another genetic model that employed constitutive vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC)/cardiomyocyte EGFR loss was unable to dissociate the impact of EGFR deletion in VSMC from cardiomyocytes on remodeling in an adult HF model73, 74. Further, pharmacologic studies using EGFR inhibitors are fraught with interpretability issues, especially regarding agent selectivity profiles75, and have produced variable and conflicting reports regarding the impact of EGFR inhibition on cardiac function and survival13, 16, 67, 76, 77. These issues have prevented succinct in vivo analysis of the impact of GPCR-mediated EGFR transactivation on cardiac function and survival during HF, or even EGFR signaling in more generalized contexts of HF. Future work on the impact of GPCR-mediated EGFR transactivation on cardiac function and remodeling in relevant in vivo systems will thus benefit from the development of refined genetic models.

Table 1.

Evidence for the involvement of GPCR-mediated EGFR transactivation in cardiac remodeling processes (reference numbers indicated)

| In vitro | In vivo | Ex vivo | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPCR | Hypertrophy | Survival | Proliferation | Hypertrophy | Survival | Fibrosis | Inflammation | Contractility* |

| Adenosine 1A Receptor (A1AR) | 13 | |||||||

| a1 Adrenergic Receptor (α1AR) | 17, 19 | 19 | 17 | |||||

| b-Adrenergic Receptor (βAR) | 18 | 15 | 67 | 16, 67 | 67 | 67 | ||

| Angiotensin II Type 1A Receptor (AT1R) |

24 | 22 | 23 | |||||

| Bradykinin Receptor (BR) | 26 | |||||||

| d-Opioid Receptor (δOR) | 27 | |||||||

| Endothelin Receptor | 28 | |||||||

| Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor M2 (M2R) |

30 | |||||||

| Prostaglandin E2 Receptor 4 (EP4) |

31 | |||||||

| Protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR1) |

33 | 32 | ||||||

| Urotensin II Receptor (UT-IIR) | 36, 37 | |||||||

I/R-induced contractile dysfunction

Acknowledgments

Adult feline ventricular cardiomyocytes were generously provided by Dr. Steven R. Houser.

Funding: NIH grant HL105414 to DGT.

References

- 1.Salazar NC, Chen J, Rockman HA. Cardiac gpcrs: Gpcr signaling in healthy and failing hearts. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2007;1768:1006–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swaney JS, Roth DM, Olson ER, Naugle JE, Meszaros JG, Insel PA. Inhibition of cardiac myofibroblast formation and collagen synthesis by activation and overexpression of adenylyl cyclase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:437–442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408704102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snead AN, Insel PA. Defining the cellular repertoire of gpcrs identifies a profibrotic role for the most highly expressed receptor, protease-activated receptor 1, in cardiac fibroblasts. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2012;26:4540–4547. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-213496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tilley DG. G protein-dependent and g protein-independent signaling pathways and their impact on cardiac function. Circ Res. 2011;109:217–230. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.231225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Uva G, Aharonov A, Lauriola M, Kain D, Yahalom-Ronen Y, Carvalho S, Weisinger K, Bassat E, Rajchman D, Yifa O, Lysenko M, Konfino T, Hegesh J, Brenner O, Neeman M, Yarden Y, Leor J, Sarig R, Harvey RP, Tzahor E. Erbb2 triggers mammalian heart regeneration by promoting cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation. Nature cell biology. 2015;17:627–638. doi: 10.1038/ncb3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carraway KL, 3rd, Cantley LC. A neu acquaintance for erbb3 and erbb4: A role for receptor heterodimerization in growth signaling. Cell. 1994;78:5–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90564-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fedele C, Riccio G, Malara AE, D'Alessio G, De Lorenzo C. Mechanisms of cardiotoxicity associated with erbb2 inhibitors. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2012;134:595–602. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hahn VS, Lenihan DJ, Ky B. Cancer therapy-induced cardiotoxicity: Basic mechanisms and potential cardioprotective therapies. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2014;3:e000665. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris RC, Chung E, Coffey RJ. Egf receptor ligands. Experimental cell research. 2003;284:2–13. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider MR, Wolf E. The epidermal growth factor receptor ligands at a glance. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218:460–466. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang Y, Bharill S, Karandur D, Peterson SM, Marita M, Shi X, Kaliszewski MJ, Smith AW, Isacoff EY, Kuriyan J. Molecular basis for multimerization in the activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. eLife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.14107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daub H, Weiss FU, Wallasch C, Ullrich A. Role of transactivation of the egf receptor in signalling by g-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 1996;379:557–560. doi: 10.1038/379557a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams-Pritchard G, Knight M, Hoe LS, Headrick JP, Peart JN. Essential role of egfr in cardioprotection and signaling responses to a1 adenosine receptors and ischemic preconditioning. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H2161–H2168. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00639.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Germack R, Griffin M, Dickenson JM. Activation of protein kinase b by adenosine a1 and a3 receptors in newborn rat cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37:989–999. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J, Eckhart AD, Eguchi S, Koch WJ. Beta-adrenergic receptor-mediated DNA synthesis in cardiac fibroblasts is dependent on transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor and subsequent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32116–32123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204895200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noma T, Lemaire A, Naga Prasad SV, Barki-Harrington L, Tilley DG, Chen J, Le Corvoisier P, Violin JD, Wei H, Lefkowitz RJ, Rockman HA. Beta-arrestin-mediated beta1-adrenergic receptor transactivation of the egfr confers cardioprotection. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2445–2458. doi: 10.1172/JCI31901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Zhang H, Liao W, Song Y, Ma X, Chen C, Lu Z, Li Z, Zhang Y. Transactivated egfr mediates alpha(1)-ar-induced stat3 activation and cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1941–H1951. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00338.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grisanti LA, Talarico JA, Carter RL, Yu JE, Repas AA, Radcliffe SW, Tang HA, Makarewich CA, Houser SR, Tilley DG. Beta-adrenergic receptor-mediated transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor decreases cardiomyocyte apoptosis through differential subcellular activation of erk1/2 and akt. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;72:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleine-Brueggeney M, Gradinaru I, Babaeva E, Schwinn DA, Oganesian A. Alpha1a-adrenoceptor genetic variant induces cardiomyoblast-to-fibroblast-like cell transition via distinct signaling pathways. Cellular signalling. 2014;26:1985–1997. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo J, Gertsberg Z, Ozgen N, Steinberg SF. P66shc links alpha1-adrenergic receptors to a reactive oxygen species-dependent akt-foxo3a phosphorylation pathway in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2009;104:660–669. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.186288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Giusti VC, Nolly MB, Yeves AM, Caldiz CI, Villa-Abrille MC, Chiappe de Cingolani GE, Ennis IL, Cingolani HE, Aiello EA. Aldosterone stimulates the cardiac na(+)/h(+) exchanger via transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Hypertension. 2011;58:912–919. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.176024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murasawa S, Mori Y, Nozawa Y, Gotoh N, Shibuya M, Masaki H, Maruyama K, Tsutsumi Y, Moriguchi Y, Shibazaki Y, Tanaka Y, Iwasaka T, Inada M, Matsubara H. Angiotensin ii type 1 receptor-induced extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase activation is mediated by ca2+/calmodulin-dependent transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor. Circ Res. 1998;82:1338–1348. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.12.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhai P, Galeotti J, Liu J, Holle E, Yu X, Wagner T, Sadoshima J. An angiotensin ii type 1 receptor mutant lacking epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation does not induce angiotensin ii-mediated cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2006;99:528–536. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000240147.49390.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas WG, Brandenburger Y, Autelitano DJ, Pham T, Qian H, Hannan RD. Adenoviral-directed expression of the type 1a angiotensin receptor promotes cardiomyocyte hypertrophy via transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Circ Res. 2002;90:135–142. doi: 10.1161/hh0202.104109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Overland AC, Insel PA. Heterotrimeric g proteins directly regulate mmp14/membrane type-1 matrix metalloprotease: A novel mechanism for gpcr-egfr transactivation. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:9941–9947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C115.647073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Methner C, Donat U, Felix SB, Krieg T. Cardioprotection of bradykinin at reperfusion involves transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor via matrix metalloproteinase-8. Acta physiologica. 2009;197:265–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.02018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forster K, Kuno A, Solenkova N, Felix SB, Krieg T. The delta-opioid receptor agonist dadle at reperfusion protects the heart through activation of pro-survival kinases via egf receptor transactivation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1604–H1608. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00418.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Correa MV, Nolly MB, Caldiz CI, de Cingolani GE, Cingolani HE, Ennis IL. Endogenous endothelin 1 mediates angiotensin ii-induced hypertrophy in electrically paced cardiac myocytes through egfr transactivation, reactive oxygen species and nhe-1. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology. 2014;466:1819–1830. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1413-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kodama H, Fukuda K, Takahashi T, Sano M, Kato T, Tahara S, Hakuno D, Sato T, Manabe T, Konishi F, Ogawa S. Role of egf receptor and pyk2 in endothelin-1-induced erk activation in rat cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:139–150. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miao Y, Bi XY, Zhao M, Jiang HK, Liu JJ, Li DL, Yu XJ, Yang YH, Huang N, Zang WJ. Acetylcholine inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha activated endoplasmic reticulum apoptotic pathway via egfr-pi3k signaling in cardiomyocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230:767–774. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mendez M, LaPointe MC. Pge2-induced hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes involves ep4 receptor-dependent activation of p42/44 mapk and egfr transactivation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2111–H2117. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00838.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabri A, Short J, Guo J, Steinberg SF. Protease-activated receptor-1-mediated DNA synthesis in cardiac fibroblast is via epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation: Distinct par-1 signaling pathways in cardiac fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2002;91:532–539. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000035242.96310.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chien PT, Lin CC, Hsiao LD, Yang CM. C-src/pyk2/egfr/pi3k/akt/creb-activated pathway contributes to human cardiomyocyte hypertrophy: Role of cox-2 induction. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2015;409:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hofmann U, Burkard N, Vogt C, Thoma A, Frantz S, Ertl G, Ritter O, Bonz A. Protective effects of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonist treatment after myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83:285–293. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esposito G, Perrino C, Cannavo A, Schiattarella GG, Borgia F, Sannino A, Pironti G, Gargiulo G, Di Serafino L, Franzone A, Scudiero L, Grieco P, Indolfi C, Chiariello M. Egfr trans-activation by urotensin ii receptor is mediated by beta-arrestin recruitment and confers cardioprotection in pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Basic Res Cardiol. 2011;106:577–589. doi: 10.1007/s00395-011-0163-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Onan D, Pipolo L, Yang E, Hannan RD, Thomas WG. Urotensin ii promotes hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes via mitogen-activated protein kinases. Molecular endocrinology. 2004;18:2344–2354. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu JC, Chen CH, Chen JJ, Cheng TH. Urotensin ii induces rat cardiomyocyte hypertrophy via the transient oxidization of src homology 2-containing tyrosine phosphatase and transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor. Molecular pharmacology. 2009;76:1186–1195. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.058297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forrester SJ, Kawai T, O'Brien S, Thomas W, Harris RC, Eguchi S. Epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation: Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and potential therapies in the cardiovascular system. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2016;56:627–653. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-070115-095427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maudsley S, Pierce KL, Zamah AM, Miller WE, Ahn S, Daaka Y, Lefkowitz RJ, Luttrell LM. The beta(2)-adrenergic receptor mediates extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation via assembly of a multi-receptor complex with the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9572–9580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tilley DG, Kim IM, Patel PA, Violin JD, Rockman HA. Beta-arrestin mediates beta1-adrenergic receptor-epidermal growth factor receptor interaction and downstream signaling. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:20375–20386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.005793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olivares-Reyes JA, Shah BH, Hernandez-Aranda J, Garcia-Caballero A, Farshori MP, Garcia-Sainz JA, Catt KJ. Agonist-induced interactions between angiotensin at1 and epidermal growth factor receptors. Molecular pharmacology. 2005;68:356–364. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.010637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jensen DD, Godfrey CB, Niklas C, Canals M, Kocan M, Poole DP, Murphy JE, Alemi F, Cottrell GS, Korbmacher C, Lambert NA, Bunnett NW, Corvera CU. The bile acid receptor tgr5 does not interact with beta-arrestins or traffic to endosomes but transmits sustained signals from plasma membrane rafts. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:22942–22960. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.455774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gorelik J, Wright PT, Lyon AR, Harding SE. Spatial control of the betaar system in heart failure: The transverse tubule and beyond. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;98:216–224. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watson LJ, Alexander KM, Mohan ML, Bowman AL, Mangmool S, Xiao K, Prasad SV, Rockman HA. Phosphorylation of src by phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulates beta-adrenergic receptor mediated egfr transactivation. Cellular signalling. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knowle D, Ahmed S, Pulakat L. Identification of an interaction between the angiotensin ii receptor sub-type at2 and the erbb3 receptor, a member of the epidermal growth factor receptor family. Regulatory peptides. 2000;87:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(99)00111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun H, Seyer JM, Patel TB. A region in the cytosolic domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor antithetically regulates the stimulatory and inhibitory guanine nucleotide-binding regulatory proteins of adenylyl cyclase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:2229–2233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morandell S, Stasyk T, Skvortsov S, Ascher S, Huber LA. Quantitative proteomics and phosphoproteomics reveal novel insights into complexity and dynamics of the egfr signaling network. Proteomics. 2008;8:4383–4401. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pawson T, Scott JD. Signaling through scaffold, anchoring, and adaptor proteins. Science. 1997;278:2075–2080. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nobles KN, Xiao K, Ahn S, Shukla AK, Lam CM, Rajagopal S, Strachan RT, Huang TY, Bressler EA, Hara MR, Shenoy SK, Gygi SP, Lefkowitz RJ. Distinct phosphorylation sites on the beta(2)-adrenergic receptor establish a barcode that encodes differential functions of beta-arrestin. Science signaling. 2011;4:ra51. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Butcher AJ, Prihandoko R, Kong KC, McWilliams P, Edwards JM, Bottrill A, Mistry S, Tobin AB. Differential g-protein-coupled receptor phosphorylation provides evidence for a signaling bar code. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:11506–11518. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.154526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zidar DA, Violin JD, Whalen EJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Selective engagement of g protein coupled receptor kinases (grks) encodes distinct functions of biased ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9649–9654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904361106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liggett SB. Phosphorylation barcoding as a mechanism of directing gpcr signaling. Science signaling. 2011;4:pe36. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeng SY, Chen X, Chen SR, Li Q, Wang YH, Zou J, Cao WW, Luo JN, Gao H, Liu PQ. Upregulation of nox4 promotes angiotensin ii-induced epidermal growth factor receptor activation and subsequent cardiac hypertrophy by increasing adam17 expression. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2013;29:1310–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takayanagi T, Kawai T, Forrester SJ, Obama T, Tsuji T, Fukuda Y, Elliott KJ, Tilley DG, Davisson RL, Park JY, Eguchi S. Role of epidermal growth factor receptor and endoplasmic reticulum stress in vascular remodeling induced by angiotensin ii. Hypertension. 2015;65:1349–1355. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cai J, Yi FF, Yang L, Shen DF, Yang Q, Li A, Ghosh AK, Bian ZY, Yan L, Tang QZ, Li H, Yang XC. Targeted expression of receptor-associated late transducer inhibits maladaptive hypertrophy via blocking epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. Hypertension. 2009;53:539–548. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.120816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Messaoudi S, Zhang AD, Griol-Charhbili V, Escoubet B, Sadoshima J, Farman N, Jaisser F. The epidermal growth factor receptor is involved in angiotensin ii but not aldosterone/salt-induced cardiac remodelling. PloS one. 2012;7:e30156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seta K, Sadoshima J. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 319 of the angiotensin ii type 1 receptor mediates angiotensin ii-induced trans-activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9019–9026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith NJ, Chan HW, Qian H, Bourne AM, Hannan KM, Warner FJ, Ritchie RH, Pearson RB, Hannan RD, Thomas WG. Determination of the exact molecular requirements for type 1 angiotensin receptor epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2011;57:973–980. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.166710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.George AJ, Purdue BW, Gould CM, Thomas DW, Handoko Y, Qian H, Quaife-Ryan GA, Morgan KA, Simpson KJ, Thomas WG, Hannan RD. A functional sirna screen identifies genes modulating angiotensin ii-mediated egfr transactivation. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:5377–5390. doi: 10.1242/jcs.128280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holopainen T, Rasanen M, Anisimov A, Tuomainen T, Zheng W, Tvorogov D, Hulmi JJ, Andersson LC, Cenni B, Tavi P, Mervaala E, Kivela R, Alitalo K. Endothelial bmx tyrosine kinase activity is essential for myocardial hypertrophy and remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:13063–13068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517810112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Douglas SA, Tayara L, Ohlstein EH, Halawa N, Giaid A. Congestive heart failure and expression of myocardial urotensin ii. Lancet. 2002;359:1990–1997. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08831-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen YL, Liu JC, Loh SH, Chen CH, Hong CY, Chen JJ, Cheng TH. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in urotensin ii-induced proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts. European journal of pharmacology. 2008;593:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vaudry H, Leprince J, Chatenet D, Fournier A, Lambert DG, Le Mevel JC, Ohlstein EH, Schwertani A, Tostivint H, Vaudry D. International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. Xcii. Urotensin ii, urotensin ii-related peptide, and their receptor: From structure to function. Pharmacological reviews. 2015;67:214–258. doi: 10.1124/pr.114.009480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carr R, 3rd, Schilling J, Song J, Carter RL, Du Y, Yoo SM, Traynham CJ, Koch WJ, Cheung JY, Tilley DG, Benovic JL. Beta-arrestin-biased signaling through the beta2-adrenergic receptor promotes cardiomyocyte contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606267113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen H, Ma N, Xia J, Liu J, Xu Z. Beta2-adrenergic receptor-induced transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor via src kinase promotes rat cardiomyocyte survival. Cell Biol Int. 2012;36:237–244. doi: 10.1042/CBI20110162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Talarico JA, Carter RL, Grisanti LA, Yu JE, Repas AA, Tilley DG. Beta-adrenergic receptor-dependent alterations in murine cardiac transcript expression are differentially regulated by gefitinib in vivo. PloS one. 2014;9:e99195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grisanti LA, Repas AA, Talarico JA, Gold JI, Carter RL, Koch WJ, Tilley DG. Temporal and gefitinib-sensitive regulation of cardiac cytokine expression via chronic beta-adrenergic receptor stimulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;308:H316–H330. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00635.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim IM, Tilley DG, Chen J, Salazar NC, Whalen EJ, Violin JD, Rockman HA. Beta-blockers alprenolol and carvedilol stimulate beta-arrestin-mediated egfr transactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14555–14560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804745105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wisler JW, DeWire SM, Whalen EJ, Violin JD, Drake MT, Ahn S, Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. A unique mechanism of beta-blocker action: Carvedilol stimulates beta-arrestin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16657–16662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707936104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim IM, Wang Y, Park KM, Tang Y, Teoh JP, Vinson J, Traynham CJ, Pironti G, Mao L, Su H, Johnson JA, Koch WJ, Rockman HA. Beta-arrestin1-biased beta1-adrenergic receptor signaling regulates microrna processing. Circ Res. 2014;114:833–844. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kang Y, Zhou XE, Gao X, He Y, Liu W, Ishchenko A, Barty A, White TA, Yefanov O, Han GW, Xu Q, de Waal PW, Ke J, Tan MH, Zhang C, Moeller A, West GM, Pascal BD, Van Eps N, Caro LN, Vishnivetskiy SA, Lee RJ, Suino-Powell KM, Gu X, Pal K, Ma J, Zhi X, Boutet S, Williams GJ, Messerschmidt M, Gati C, Zatsepin NA, Wang D, James D, Basu S, Roy-Chowdhury S, Conrad CE, Coe J, Liu H, Lisova S, Kupitz C, Grotjohann I, Fromme R, Jiang Y, Tan M, Yang H, Li J, Wang M, Zheng Z, Li D, Howe N, Zhao Y, Standfuss J, Diederichs K, Dong Y, Potter CS, Carragher B, Caffrey M, Jiang H, Chapman HN, Spence JC, Fromme P, Weierstall U, Ernst OP, Katritch V, Gurevich VV, Griffin PR, Hubbell WL, Stevens RC, Cherezov V, Melcher K, Xu HE. Crystal structure of rhodopsin bound to arrestin by femtosecond x-ray laser. Nature. 2015;523:561–567. doi: 10.1038/nature14656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Briasoulis A, Palla M, Afonso L. Meta-analysis of the effects of carvedilol versus metoprolol on all-cause mortality and hospitalizations in patients with heart failure. The American journal of cardiology. 2015;115:1111–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.01.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Threadgill DW, Dlugosz AA, Hansen LA, Tennenbaum T, Lichti U, Yee D, LaMantia C, Mourton T, Herrup K, Harris RC, et al. Targeted disruption of mouse egf receptor: Effect of genetic background on mutant phenotype. Science. 1995;269:230–234. doi: 10.1126/science.7618084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schreier B, Rabe S, Schneider B, Bretschneider M, Rupp S, Ruhs S, Neumann J, Rueckschloss U, Sibilia M, Gotthardt M, Grossmann C, Gekle M. Loss of epidermal growth factor receptor in vascular smooth muscle cells and cardiomyocytes causes arterial hypotension and cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2013;61:333–340. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.196543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fabian MA, Biggs WH, 3rd, Treiber DK, Atteridge CE, Azimioara MD, Benedetti MG, Carter TA, Ciceri P, Edeen PT, Floyd M, Ford JM, Galvin M, Gerlach JL, Grotzfeld RM, Herrgard S, Insko DE, Insko MA, Lai AG, Lelias JM, Mehta SA, Milanov ZV, Velasco AM, Wodicka LM, Patel HK, Zarrinkar PP, Lockhart DJ. A small molecule-kinase interaction map for clinical kinase inhibitors. Nature biotechnology. 2005;23:329–336. doi: 10.1038/nbt1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Barrick CJ, Yu M, Chao HH, Threadgill DW. Chronic pharmacologic inhibition of egfr leads to cardiac dysfunction in c57bl/6j mice. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2008;228:315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Akhtar S, Yousif MH, Chandrasekhar B, Benter IF. Activation of egfr/erbb2 via pathways involving erk1/2, p38 mapk, akt and foxo enhances recovery of diabetic hearts from ischemia-reperfusion injury. PloS one. 2012;7:e39066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]