Abstract

Background

College-related alcohol beliefs, or beliefs that drinking alcohol is central to the college experience, have been shown to robustly predict alcohol-related outcomes among college students. Given the strength of the associations, it is imperative to understand more proximal factors (i.e., closer in causal chain leading to alcohol-related outcomes) that can explain these associations.

Objectives

The current research examined alcohol protective behavioral strategies (PBS) as a potential mediator of the association between college-related alcohol beliefs and alcohol outcomes among college student drinkers.

Method

Participants were undergraduate students from a large southeastern university (Sample 1; n = 561) and a large southwestern university (Sample 2; n = 563) the United States that consumed alcohol at least once in the previous month.

Results

Path analysis was conducted examining the concurrent associations between college-related alcohol beliefs, PBS use (both as a single facet and multidimensionally), alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related consequences (i.e., double-mediation). In both samples, there was a significant double-mediated association that suggested that higher college-related alcohol beliefs is associated with lower PBS use (single facet), which is associated with higher alcohol consumption and alcohol-related consequences. Multidimensionally, only one double-mediation effect (in Sample 2 only) was significant (i.e., college-related alcohol beliefs → manner of drinking PBS → alcohol consumption → alcohol-related consequences).

Conclusions/Importance

These results suggest that targeting these college-related alcohol beliefs as well as PBS use are promising targets for college alcohol interventions. Limitations and future directions are discussed.

Keywords: alcohol, college- alcohol beliefs, consequences, college students, protective behavioral strategies

The National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) has recognized alcohol misuse as the most important health hazard for college students due to the high rates of heavy drinking, negative alcohol-related consequences, and prevalence of alcohol use disorders (NIAAA, 2015). Of the 8 million college students in the United States, nearly half report heavy episodic drinking (Hingson, Zha, & Weitzman, 2009). For a point of reference, the number of heavy drinkers in college is equivalent to the population of Los Angeles, CA, the second largest city in the United States (Los Angeles, CA population estimate: 3.9 million people; www.census.gov). Alcohol use on college campuses results in over 1,700 deaths per year, as well as physical, academic, and social problems for tens of thousands of students nationwide (Hingson, Heeren, Winter, & Wechsler, 2005). The National Advisory Council on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2002) asserts that the culture of drinking is deep-rooted at each level of college student’s environments. Consistent with this assertion, perceived norms of others’ drinking has received much research attention and has driven the primary intervention approach targeting college students: personalized normative feedback interventions (Miller et al., 2013). Osberg and colleagues state that, “engaging in heavy drinking during the college years has long been considered a rite of passage by many” (Osberg, Insana, Eggert, & Billingsley, 2011, p. 333), leading to their introduction of the concept of college-related alcohol beliefs, which has been described as internalized college drinking norms or alcohol beliefs regarding the importance of drinking to the college experience (Osberg et al., 2011; Osberg et al., 2010; Osberg et al., 2012).

To date, several studies have found college-related alcohol beliefs as a risk factor that is associated with alcohol use and related consequences among college students (Hustad, Pearson, Neighbors, & Borsari, 2014; Osberg et al., 2010; Osberg et al., 2011; Osberg, Billingsley, Eggert, & Insana, 2012; Pearson & Hustad, 2014). Moreover, across two studies, the extent to which one has internalized his or her beliefs about alcohol use as a part of college life has been shown to mediate the relationships between impulsivity and sensation seeking and alcohol use, as well as to a lesser degree the relationship between these personality factors and alcohol related consequences (Hustad et al., 2014; Pearson & Hustad, 2014). In fact, these college-related alcohol beliefs have been shown to have stronger associations with alcohol outcomes than many other established predictors of alcohol outcomes (e.g., descriptive norms, injunctive norms, alcohol expectancies; Hustad et al., 2014; Osberg et al., 2012; Pearson & Hustad, 2014). Whereas multiple studies have demonstrated that college-related alcohol beliefs mediate the relationships between other more distal factors (e.g., personality traits) and alcohol outcomes, no studies have examined potential mediators of the relationship between college-related alcohol beliefs and alcohol outcomes. Given the strength of the associations between college-related alcohol beliefs and alcohol outcomes, it is imperative to understand more proximal factors (i.e., closer in causal chain leading to alcohol-related outcomes) that can explain these associations.

One construct that has received considerable attention and has been consistently shown to have a negative association with alcohol use and alcohol related consequences is use of protective behavioral strategies (PBS) (see Pearson, 2013; Prince, Carey, & Maisto, 2013 for reviews). PBS are “behaviors used immediately prior to, during, and/or after drinking that reduce alcohol use, intoxication, and/or alcohol-related harm” (Pearson, 2013, p. 1030). Examples of alcohol PBS identified in previous work (Protective Behavior Strategies Scale, PBSS; Martens et al., 2005) include limiting/stopping drinking (e.g., “stop drinking at a predetermined time”), manner of drinking (e.g., “drink slowly, rather than gulp or chug”), and serious harm reduction (e.g., “know where your drink has been at all times”).

We consider whether PBS use mediates the associations between college-related alcohol beliefs and alcohol-related outcomes for three reasons. First, because PBS use occurs during a drinking event itself, it is clearly one of the most proximal antecedents to alcohol-related outcomes. Second, PBS use has been shown to mediate the effects of impulsivity-like traits (Pearson, Kite, & Henson, 2012), conscientiousness (Martens et al., 2009), age of first use (Palmer, Corbin, & Cronce, 2010), self-regulation (D’Lima, Pearson, & Kelley, 2012), depressive symptoms (Martens et al., 2008), and drinking motives (Ebersole, Noble, & Madson, 2012; LaBrie, Lac, Kenney, & Mirza, 2011; Martens, Ferrier, & Cimini, 2007) on alcohol outcomes. Recently, most of these findings have been replicated (Bravo, Prince, & Pearson, 2015, 2016), adding confidence to the role of PBS as an important mediator of the effects of many constructs on alcohol outcomes. Third, PBS use has been shown to mediate the effects of several interventions targeting other alcohol beliefs (e.g., descriptive norms; Barnett, Murphy, Colby, & Monti, 2007, Larimer et al., 2007; Murphy et al., 2012). Altogether, these observations suggest that holding specific alcohol-related beliefs may impact whether one decides to engage in PBS use, which in turn relates directly to both alcohol use and alcohol related consequences.

Further, although the preponderance of PBS research has focused on a total score of PBS (Pearson, 2013), more recent research has demonstrated unique/differential relationships between specific strategies (i.e., limiting/stopping drinking, manner of drinking, and serious harm reduction) and alcohol outcomes (Bravo et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2012; Pearson, Prince, & Bravo, 2016). Thus, examining specific strategies as mediators of the relationship between college-related alcohol beliefs and alcohol outcomes is warranted.

Purpose of Present Study

The purpose of our study is to extend research on the associations among college-related alcohol beliefs, PBS use, and alcohol outcomes. Precisely, we examine alcohol PBS use (both as a single facet and multidimensionally) as a potential mediator of the association between college-related alcohol beliefs and alcohol outcomes among college students. We examined a double mediation model (i.e., sequential mediation model) such that higher beliefs about alcohol and the college experience would relate to lower PBS use. In turn, lower PBS use would be related to higher alcohol consumption, which would relate to higher alcohol-related consequences. Further, given that the field of psychology is currently undergoing a rather strong indictment regarding effects that are not reproducible (Simmons, Nelson, & Simonsohn, 2011); we examined the proposed models across two independent samples of college students.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were recruited from psychology department research pools at a large southeastern university (Sample 1; n = 774) and a large southwestern university (Sample 2; n = 594). For this present study, only data from students that consumed alcohol at least once in the previous month were included in the final analysis from each sample (Sample 1, n = 561; Sample 2, n = 563). Demographics across institutions are described in Table 1. Both studies were approved by an institutional review board and students received research participation credits for participating.

Table 1.

Demographics of orignial samples

| Sample 1 (n = 561) |

Sample 2 (n = 563) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Gender | n (%) | n (%) |

|

| ||

| Male | 158 (28.2) | 203 (36.1) |

| Female | 396 (70.6) | 359 (63.8) |

| Missing | 7 (1.2) | 1 (0.2) |

|

| ||

| Age | n (%) | n (%) |

|

| ||

| M (SD) | 22.22 (6.79) | 20.11 (3.67) |

| 18 | 72 (12.8) | 198 (35.2) |

| 19 | 79 (14.1) | 131 (23.3) |

| 20 | 107 (19.1) | 83 (14.7) |

| 21+ | 292 (52.1) | 148 (26.3) |

| Missing | 11 (2.0) | 3 (0.5) |

|

| ||

| Race/Ethnicity | n (%) | n (%) |

|

| ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 20 (3.6) | 33 (5.9) |

| Asian | 16 (2.9) | 30 (5.3) |

| Black/African American | 190 (33.9) | 28 (5.0) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 7 (1.2) | 4 (0.7) |

| White, non-Hispanic | White | 322 (57.4) | 186 (33.0) |

| Other | 16 (2.9) | 6 (1.1) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 63 (11.2) | 313 (55.6) |

| Missing | 2 (0.4) | 5 (0.9) |

|

| ||

| Education | n (%) | n (%) |

|

| ||

| Freshman | 116 (20.7) | 248 (44.0) |

| Sophomore | 114 (20.3) | 129 (22.9) |

| Junior | 168 (29.9) | 90 (16.0) |

| Senior | 157 (28.0) | 92 (16.3) |

| Graduate Student | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.5) |

| Missing | 6 (1.1) | 1 (0.2) |

Note. Race and ethnicity were assessed with separate checkbox items (i.e., could select multiple options) in both samples. It is important to note that the samples significantly differed on all demographic variables.

Measures

College-related alcohol beliefs

College-related alcohol beliefs were assessed using the 15-item College Life Alcohol Salience Scale (CLASS; Osberg et al., 2010). Measured on a 5-point response scale (Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Uncertain or Unsure, Agree, and Strongly Agree). Sample items include, “Parties with alcohol are an integral part of college life” and “To become drunk is a college rite of passage”. Item scores (reverse-coded if needed) were averaged to create a total score such that higher values indicate higher beliefs about alcohol and the college experience (Sample 1, α = .90; Sample 2, α = .90).

PBS

Past month PBS use was assessed with the 15-item Protective Behavioral Strategies Survey (PBSS; Martens et al., 2005) measured on a 6-point response scale (Never, Rarely, Occasionally, Sometimes, Usually, and Always). We changed a previously reverse-coded item (“drink shots of liquor”) to be consistent with the remaining items (“avoid drinking shots of liquor”). Three subscales identified in previous work include: Limiting/Stopping Drinking (7 items; Sample 1, α = .85; Sample 2, α = .87), Manner of Drinking (5 items; Sample 1, α = .86; Sample 2, α = .84), and Serious Harm Reduction (3 items; Sample 1, α = 82; Sample 2, α = .83). Further, for the present study, a total PBS composite score was also calculated (Sample 1, α = .90; Sample 2, α = .90).

Alcohol consumption

Alcohol consumption was measured with a modified version of the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins et al., 1985). Participants indicated how much they drink during a typical week in the past 30 days using a 7-day grid from Monday to Sunday. We summed number of standard drinks consumed on each day of the typical drinking week.

Alcohol-related consequences

Alcohol-related consequences were assessed using a checklist version of the Brief-Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (B-YAACQ; Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005) where participants checked a box for each alcohol-related consequences that they experienced in the past month (e.g., “While drinking, I have said or done embarrassing things,” “I have felt badly about myself because of my drinking”). We summed items to create a measure reflective of the number of distinct alcohol-related consequences experienced in the past 30 days (Sample 1, α = .91; Sample 2, α = .90). Due to experimenter error in Sample 2, two items were given as one item, resulting in a 23-item version of the measure. Data were analyzed including/excluding this compound item (the two versions were nearly perfectly correlated r = .998), and no differences were found in the pattern of results.

Statistical Analyses

We used path analysis (Mplus 7; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) to test the two proposed double-mediation models: 1) college-related alcohol beliefs →PBS use total score→alcohol consumption→ alcohol-related consequences, 2) college-related alcohol beliefs →PBS use subscales→ alcohol consumption → alcohol-related consequences across two distinct datasets. Gender was modeled as a covariate in all models (i.e., predictor of all other variables in the models). We examined the total, direct, and indirect effects of each predictor variable on outcomes using bias-corrected bootstrapped estimates (Efron & Tibshirani, 1993) based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples, which provides a powerful test of mediation (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007) and is robust to small departures from normality (Erceg-Hurn & Mirosevich, 2008). Parameters were estimated using maximum likelihood estimation, and missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood, which is more efficient and has less bias than alternative procedures (Enders, 2001; Enders & Bandalos, 2001). Statistical significance was determined by 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals that do not contain zero.

Results

Bivariate Relationships

We conducted bivariate correlations to examine the associations among college-related alcohol beliefs, PBS use, alcohol consumption (measured as typical drinks per week), and alcohol-related consequences across both datasets. Zero-order correlations across both samples are summarized in Table 2. In sample 1, college-related alcohol beliefs had a weak negative correlation with PBS total score, limiting/stopping drinking and a moderate negative correlation with manner of drinking. Surprisingly, college-related alcohol beliefs did not have a significant correlation with serious harm reduction. With regards to alcohol outcomes, college-related alcohol beliefs had a moderately positive relationship both alcohol consumption and alcohol-related consequences. As expected, PBS use and subscales were all negatively correlated with alcohol outcomes, although a weak association. In Sample 2, results were nearly identical (i.e., similar strengths) except that college-related alcohol beliefs had a significantly weak negative correlation with serious harm reduction. Finally, across both samples, females tended to endorse higher PBS use and lower amounts of alcohol consumption (alcohol-related consequences was not significant).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among all observed variables in Sample 1 (above diagonal) and Sample 2 (below diagonal)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | M | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. College-related alcohol beliefs | --- | −.26 | −.17 | −.37 | −.01 | .35 | .35 | −.04 | 2.78 | 0.77 | |

| 2. PBS Total Score | −.30 | --- | .90 | .84 | .61 | −.27 | −.26 | .16 | 3.60 | 1.08 | |

| 3. Limiting/Stopping Drinking | −.21 | .90 | --- | .60 | .40 | −.22 | −.18 | .12 | 3.15 | 1.27 | |

| 4. Manner of Drinking | −.35 | .81 | .60 | --- | .35 | −.28 | −.29 | .13 | 3.39 | 1.39 | |

| 5. Serious Harm Reduction | −.12 | .58 | .40 | .29 | --- | −.13 | −.15 | .18 | 4.99 | 1.28 | |

| 6. Alcohol Consumption | .31 | −.23 | −.22 | −.27 | −.10 | --- | .48 | −.27 | 7.79 | 8.61 | |

| 7. Alcohol-related Consequences | .43 | −.32 | −.18 | −.26 | −.22 | .40 | --- | −.07 | 4.88 | 4.77 | |

| 8. Gender | −.12 | .16 | .20 | .13 | .31 | −.22 | −.06 | --- | 0.21 | 0.45 | |

| M | 2.79 | 3.61 | 3.28 | 3.23 | 5.02 | 7.72 | 6.33 | 0.14 | |||

| SD | 0.74 | 1.05 | 1.30 | 1.32 | 1.24 | 8.14 | 5.26 | 0.48 | |||

Note. Significant correlations are in bold typeface for emphasis and were determined by a 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval (based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples) that does not contain zero. Gender was coded −.5 = men, .5 = women. It is important to note that Sample 2 reported significantly higher alcohol-related consequences than sample 1. The Samples did not differ on any other study variable.

Model 1 (PBS Total Score)

The total, total indirect, specific indirect, and direct effects across both samples are summarized in Table 3. Across both samples, PBS use mediated the relationship between college-related alcohol beliefs and alcohol consumption (Sample 1, indirect β = .04; Sample 2, indirect β = .05), such that higher alcohol beliefs was associated with higher alcohol use via lower PBS use. PBS use accounted for 10.29% of the total effect of college-related alcohol beliefs on alcohol consumption in Sample 1 and 11.21% of the total effect in Sample 2. PBS use also mediated the relationship between college-related alcohol beliefs and alcohol-related consequences (Sample 1, indirect β = .03; Sample 2, indirect β = .05), such that higher alcohol beliefs was associated with higher alcohol-related consequences via lower PBS use. PBS use accounted for 7.80% of the total effect of college-related alcohol beliefs on alcohol-related consequences in Sample 1 and 12.12% of the total effect in Sample 2. Taken together with the mediating effects of alcohol consumption (see Table 3), double-mediated effects (i.e., college-related alcohol beliefs → PBS use → alcohol consumption → alcohol-related consequences) across both samples were significant (Sample 1, indirect β = .01; Sample 2 indirect β = .01). PBS use and alcohol consumption accounted for 46.26% (Sample 1) and 31.65% (Sample 2) of the total effect of college-related alcohol beliefs on alcohol-related consequences.

Table 3.

Summary of total, indirect, and direct effects of college alcohol beliefs and PBS total score on alcohol outcomes

| Replication Datasets | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | ||

|

| ||||

| Outcome Variable: | Alcohol Consumption | Alcohol Consumption | ||

|

| ||||

| Predictor Variable: College Alcohol Beliefs | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI |

|

| ||||

| Total | .346 | .270, .421 | .290 | .220, .361 |

| Indirect (PBS total score) | .036 | .012, .059 | .033 | .005, .061 |

| Directa | .310 | .232, .388 | .258 | .186, .329 |

|

| ||||

| Outcome Variable: | Alcohol- Related Consequences | Alcohol- Related Consequences | ||

|

| ||||

| Predictor Variable: College Alcohol Beliefs | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI |

|

| ||||

| Total | .353 | .286, .420 | .429 | .362, .496 |

| Total indirectb | .163 | .119, .207 | .136 | .095, .176 |

| PBS Total Score | .027 | .005, .049 | .052 | .025, .079 |

| Alcohol Consumption | .122 | .084, .159 | .074 | .045, .104 |

| PBS Total Score-Alcohol Consumption | .014 | .004, .023 | .009 | .000, .018 |

| Directc | .190 | .118, .262 | .293 | .216, .371 |

|

| ||||

| Predictor Variable: PBS Total Score | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI |

|

| ||||

| Total | −.164 | −.237, −.090 | −.220 | −.303, −.137 |

| Indirect (PBS total score) | −.055 | −.086, −.024 | −.034 | −.064, −.003 |

| Directc | −.108 | −.177, −.040 | −.186 | −.266, −.107 |

Note. Significant effects are in bold typeface for emphasis and were determined by a 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval (based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples) that does not contain zero.

Reflects the direct effect between college-related beliefs and alcohol consumption.

Reflects the combined indirect effects via PBS Total Score, alcohol consumption, and PBS Total Score via alcohol consumption.

Reflects the direct effect between college-related beliefs and alcohol-related consequences. Total effects reflect the combined direct and indirect effects.

Model 2 (Multidimensional PBS Subscales)

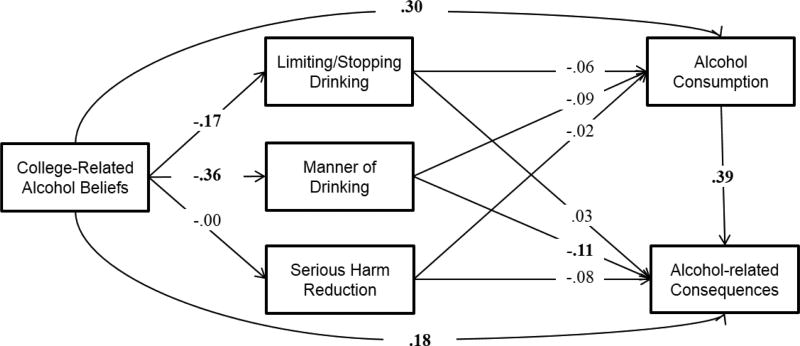

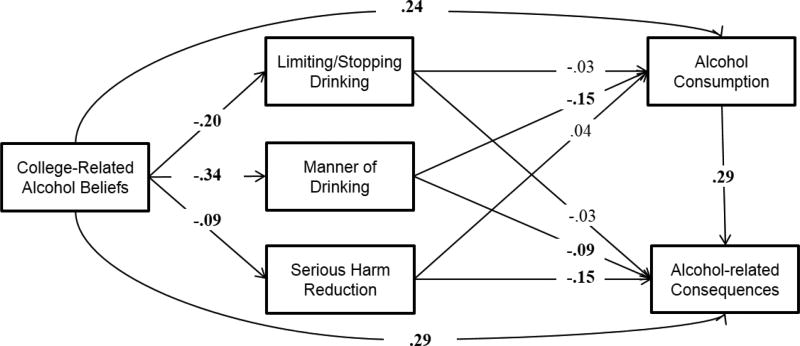

The total, total indirect, specific indirect, and direct effects across both samples are summarized in Table 4. Direct effects are shown in Figures 1 (Sample 1) and 2 (Sample 2). Across both samples, manner of drinking was the only PBS subscale to uniquely (i.e., controlling for other PBS subscales) mediate the relationship between college-related alcohol beliefs and alcohol-related consequences (Sample 1, indirect β = .04, Sample 2, indirect β = .03), such that higher alcohol beliefs was associated with higher alcohol-related consequences via lower manner of drinking. Manner of drinking accounted for 10.86% of the total effect of college-related alcohol beliefs on alcohol-related consequences in Sample 1 and 7.48% of the total effect in Sample 2. With regards to alcohol consumption, only in Sample 2 did manner of drinking uniquely mediate the relationship between college-related alcohol beliefs and alcohol consumption (indirect β = .05), accounting for 16.99% of the total effect. Taken together, a double-mediation effect (in Sample 2 only) was significant (i.e., college-related alcohol beliefs → manner of drinking → alcohol consumption → alcohol-related consequences), indirect β = .01. Serious harm reduction and limiting/stopping drinking did not uniquely significantly mediate (while controlling for other PBS subscales) the associations between college-related alcohol beliefs and alcohol outcomes across both datasets (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of total, indirect, and direct effects of college alcohol beliefs and PBS subscales on alcohol outcomes

| Replication Datasets | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | ||

|

| ||||

| Outcome Variable: | Alcohol Consumption | Alcohol Consumption | ||

|

| ||||

| Predictor Variable: College Alcohol Beliefs | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI |

|

| ||||

| Total | .346 | .270, .421 | .290 | .220, .361 |

| Total indirecta | .044 | .011, .077 | .051 | .019, .084 |

| Limiting/Stopping Drinking | .011 | −.005, .026 | .005 | −.012, .023 |

| Manner of Drinking | .033 | −.002, .068 | .049 | .018, .080 |

| Serious Harm Reduction | .000 | −.005, .005 | −.003 | −.012, .005 |

| Directb | .302 | .217, .386 | .239 | .186, .329 |

|

| ||||

| Outcome Variable: | Alcohol- Related Consequences | Alcohol- Related Consequences | ||

|

| ||||

| Predictor Variable: College Alcohol Beliefs | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI |

|

| ||||

| Total | .353 | .286, .420 | .429 | .362, .496 |

| Total indirectc | .170 | .120, .220 | .136 | .093, .180 |

| Limiting/Stopping Drinking | −.004 | −.018, .009 | .007 | −.010, .023 |

| Manner of Drinking | .038 | .005, .072 | .032 | .000, .065 |

| Serious Harm Reduction | .000 | −.009, .009 | .013 | −.003, .029 |

| Alcohol Consumption | .118 | .080, .157 | .070 | .041, .099 |

| Limiting/Stopping Drinking-Alcohol Consumption | .004 | −.002, .010 | .002 | −.004, .007 |

| Manner of Drinking-Alcohol Consumption | .013 | −.001, .002 | .014 | .004, .024 |

| Serious Harm Reduction-Alcohol Consumption | .000 | −.002, .002 | −.001 | −.004, .002 |

| Directd | .183 | .118, .262 | .293 | .214, .371 |

Note. Significant effects are in bold typeface for emphasis and were determined by a 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval (based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples) that does not contain zero.

Reflects the combined indirect effects via limiting/stopping drinking, manner of drinking, and serious harm reduction.

Reflects the direct effect between college-related beliefs and alcohol consumption.

Reflects the combined indirect effects via limiting/stopping drinking, manner of drinking, serious harm reduction, alcohol consumption, limiting/stopping drinking-alcohol consumption, manner of drinking-alcohol consumption, and serious harm reduction-alcohol consumption.

Reflects the direct effect between college-related beliefs and alcohol-related consequences. Total effects reflect the combined direct and indirect effects.

Figure 1.

Depicts the standardized estimated model in Sample 1 (n = 561). * p < .05. Significant standardized effects are in bold typeface for emphasis and were determined by a 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval (based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples) that does not contain zero. The disturbance among PBS subscales were allowed to correlate and were all significant. These paths and significant effects of the covariate (i.e., gender) are available from the authors upon request.

Figure 2.

Depicts the standardized estimated model in Sample 2 (n = 563). * p < .05. Significant standardized effects are in bold typeface for emphasis and were determined by a 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval (based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples) that does not contain zero. The disturbance among PBS subscales were allowed to correlate and were all significant. These paths and significant effects of the covariate (i.e., gender) are available from the authors upon request.

Discussion

In the college student drinking literature, perceived norms of others’ drinking has received much research attention and has driven the primary intervention approach targeting college students: personalized normative feedback interventions (Miller et al., 2013). More recently, Osberg and colleagues (Osberg et al., 2011; Osberg et al., 2010; Osberg et al., 2012) developed and validated the College Life Alcohol Salience Scale (CLASS), which can be described as internalized college drinking norms or alcohol beliefs regarding the importance of drinking to the college experience. The present study examined whether use of alcohol protective behavioral strategies (PBS) may account for the effects of these college-related alcohol beliefs on alcohol-related outcomes among college students.

Across two samples, we found that overall PBS use, and specifically the use of Manner of Drinking PBS, partially mediated the effects of college-related alcohol beliefs on both alcohol consumption and alcohol-related consequences. Thus, college students who believe that drinking is an essential part of the college experience tend to be at more risk of elevated alcohol use and consequence due to their usage of fewer PBS. These findings support a growing literature that demonstrates PBS use to be a proximal mediator of a wide range of factors ranging from personality traits to drinking motives (Pearson, 2013; Prince et al., 2013). Further, this mediated effect provides some preliminary support for two notions that have potentially important clinical implications discussed in more detail below. First, targeting elevated college-related alcohol beliefs may result in decreased alcohol-related harm via increased use of PBS. Second, targeting the under-usage of PBS may be an effective strategy for reducing alcohol-related harm among individuals with elevated college-related alcohol beliefs.

Although PBS use partially mediated the effects of college-related alcohol beliefs, they were also direct predictors of both alcohol use and consequences. These college-related alcohol beliefs have been shown to be robust predictors of alcohol-related outcomes among college students (Osberg et al., 2010, 2011, 2012), have been shown to concurrently mediate the effects of various personality traits on alcohol-related outcomes (Hustad et al., 2014; Pearson & Hustad, 2014), and have been shown to prospectively mediate the effects of exposure to pro-college drinking movies (Osberg et al., 2012). These previous findings suggest that perhaps college student alcohol interventions could target these college-related alcohol beliefs directly to improve alcohol-related outcomes in this population. As suggested previously (Pearson & Hustad, 2014), college-related alcohol beliefs could be targeted as a part of social norms interventions, which could highlight the discrepancy between one’s own college-related alcohol beliefs and those of other college students. Although not directly targeted, it is possible that college-related alcohol beliefs change in response to standard personalized normative feedback interventions, or even in response to interventions that encourage alcohol-free leisure activities (Murphy, Barnett, & Colby, 2006; Yarnal, Qian, Hustad, & Sims, 2013). Given the promise of this construct, we argue that college-related alcohol beliefs be examined as a possible mediator of college student alcohol interventions, and these beliefs may also help to account for maturing out of alcohol use (i.e., college-related alcohol beliefs may diminish over time, covarying with the reduction in alcohol use over the college years and post-college).

Alternatively, without directly challenging the views of the centrality of drinking in the college environment, a PBS-targeted intervention could focus on contesting the notion that negative consequences are essential byproducts of drinking in college. Specifically, by using PBS effectively, one could simultaneously drink alcohol and reduce the likelihood of experiencing negative alcohol-related consequences. Further research is needed to determine if the under-usage of PBS associated with college-related alcohol beliefs in the present study and several other variables examined in other studies is due to a lower motivation to use PBS and/or a difficulty in consistently implementing PBS use.

The findings and the implications of the present study ought to be considered in light of the limitations of the present study. The cross-sectional study design prevents the demonstration of temporal precedence, which is needed to justify causal inferences. For example, we cannot use these data alone to determine whether college-related alcohol beliefs cause a reduction in the use of PBS, whether PBS use causes a decrease in college-related alcohol beliefs, or whether these associations are spurious and caused by a third variable. Further we are not able to demonstrate within-person associations or malleability of constructs. Additional support for the proposed model is needed from longitudinal (e.g., ecological momentary assessment) and experimental studies. For example, a randomized controlled trial targeting college-related alcohol beliefs and/or PBS use could be used to determine whether changes in one of these constructs result in subsequent changes in the other construct. Another limitation of this study is the sole reliance on retrospective self-report measures. Given that significant recall biases have been demonstrated with alcohol use reports in time intervals as short as one week (Ekholm, 2004; Gmel & Daeppon, 2007), the possible influence of these biases must be considered when interpreting our results. Although college-student alcohol beliefs have been shown to predict alcohol outcomes above and beyond the effects of descriptive and injunctive norms, a fuller picture of these associations would be possible if we had also assessed these other alcohol perception variables. Finally, the fact that we replicated the direct and indirect effects in the model using a total score for PBS, but not when using the subscales point out a significant limitation in the PBS field. Specifically, we have not yet determined the best way to operationalize PBS use. On the one hand, we want to avoid examining PBS use at such a broad level that we fail to distinguish specific effects of unique types of PBS. On the other hand, by examining PBS use in a too fine-grained manner, we may be drawing distinctions that are highly sample-specific or driven by chance. For example, each PBS subscale is moderately correlated with one another and similarly correlated with alcohol outcomes. In multivariate models, it is possible that differences observed throughout the literature regarding the types of PBS use that uniquely predict outcomes are driven by chance (Bravo et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2012).

Conclusion

In two independent samples, we found that PBS use partially mediated the effects of college-related alcohol beliefs on alcohol-related outcomes. This findings supports a growing literature that places PBS use as a mediator of a wide range of distal and proximal antecedents to alcohol-related outcomes. Given our study’s cross-sectional design, these findings should be interpreted with some caution; however, both the mediated and direct effects of college-related alcohol beliefs provide some preliminary support for targeting PBS use and these college-related alcohol beliefs as a part of college alcohol interventions.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources

AJB is supported by a training grant (T32-AA018108) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). MRP is supported by a career development grant from NIAAA (K01-AA023233). NIAAA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors

AJB drafted the first draft of the manuscript, wrote the method and results sections, and conducted the analyses. MAP wrote the introduction. MRP wrote the discussion. All authors conducted edits and approved of the final manuscript.

Declaration of Interest

We do not have any conflict of interest that could inappropriately influence, or be perceived to influence, our work.

References

- Barnett NP, Murphy JG, Colby SM, Monti PM. Efficacy of counselor vs. computer-delivered intervention with mandated college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2529–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo AJ, Prince MA, Pearson MR. A multiple replication examination of distal antecedents to alcohol protective behavioral strategies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2016 doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo AJ, Prince MA, Pearson MR. Does the how mediate the why? A multiple replication examination of drinking motives, alcohol protective behavioral strategies, and alcohol outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;76:872–883. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Lima GM, Pearson MR, Kelley ML. Protective behavioral strategies as a mediator and moderator of the relationship between self-regulation and alcohol-related outcomes in first-year college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:330–337. doi: 10.1037/a0026942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebersole RC, Noble JJ, Madson MB. Drinking motives, negative consequences, and protective behavioral strategies in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender college students. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling. 2012;6:337–352. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ekholm E. Influence of the recall period on self-reported alcohol intake. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;58:60–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. The impact of nonnormality on full information maximum-likelihood estimation for structural equation models with missing data. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:352–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:430–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erceg-Hurn DM, Mirosevich VM. Modern robust statistical methods: an easy way to maximize the accuracy and power of your research. American Psychologist. 2008;63:591–601. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.7.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. Required sample size to detect mediated effect. Psychological Science. 2007;18:233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmel G, Daeppen J-B. Recall bias for seven-day recall measurement of alcohol consumption among emergency department patients: Implications for case-crossover designs. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:303–310. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Herren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: Changes from 1998–2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;16:12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustad JTP, Pearson MR, Neighbors C, Borsari B. The role of alcohol perceptions as mediators between personality and alcohol-related outcomes among incoming college student drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:336–347. doi: 10.1037/a0033785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Alcoholism Clinical Experimental Research. 2005;29:1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Lac A, Kenney SR, Mirza T. Protective behavioral strategies mediate the effect of drinking motives on alcohol use among heavy drinking college students: Gender and race differences. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Fabiano PM, Stark CB, Geisner IM, Mallet KA, Lostutter TW, Cronce JM, Feeney M, Neighbors C. Personalized mailed feedback for college drinking prevention: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:285–293. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Los Angeles City, California Population. 2015 Dec 23; Retrieved from www.census.gov.

- Martens MP, Ferrier AG, Cimini MD. Do protective behavioral strategies mediate the relationship between drinking motives and alcohol use in college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:106–114. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Ferrier AG, Sheehy MJ, Corbett K, Anderson DA, Simmons A. Development of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:698–705. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Karakashian MA, Fleming KM, Fowler RM, Hatchett ES, Cimini MD. Conscientiousness, protective behavioral strategies, and alcohol use: Testing for mediated effects. Journal of Drug Education. 2009;39:273–287. doi: 10.2190/DE.39.3.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Martin JL, Hatchett ES, Fowler RM, Fleming KM, Karakashian MA, Cimini MD. Protective behavioral strategies and the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences among college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55:535–541. doi: 10.1037/a0013588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Pederson ER, LaBrie JW, Ferrier AG, Cimini MD. Measuring alcohol-related protective behavioral strategies among college students: Further examination of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Scale. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:307–315. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Leffingwell T, Claborn K, Meier E, Walters S, Neighbors C. Personalized feedback interventions for college alcohol misuse: An update of Walters & Neighbors (2005) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:909–920. doi: 10.1037/a0031174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Barnett NP, Colby SM. Alcohol-related and alcohol-free activity participation and enjoyment among college students: A behavioral theories of choice analysis. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;14:339–349. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Borsari B, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Martens MP. A randomized controlled trial of a behavioral economic supplement to brief motivational interventions for college drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:876–886. doi: 10.1037/a0028763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Seventh. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. A call to action: Changing the culture of drinking at U.S. colleges, Final report of the Task Force on College Drinking. Rockville, MD: NIAAA; 2002. NIH Pub. No. 02-5010. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. College drinking. 2015 Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/CollegeFactSheet/Collegefactsheet.pdf.

- Osberg TM, Atkins L, Buchholz L, Shirshova V, Swiantek A, Whitley J, et al. Development and validation of the College Life Alcohol Salience Scale: A measure of beliefs about the role of alcohol in college life. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(1):1–12. doi: 10.1037/a0018197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osberg TM, Billingsley K, Eggert M, Insana M. From animal house to old school: A multiple mediation analysis of the association between college drinking movie exposure and freshman drinking and its consequences. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:922–930. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osberg TM, Insana M, Eggert M, Billingsley K. Incremental validity of college alcohol beliefs in the prediction of freshman drinking and its consequences: A prospective study. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(4):333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RS, Corbin WR, Cronce JM. Protective strategies: A mediator of risk associated with age of drinking onset. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:486–491. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MR. Use of alcohol protective behavioral strategies among college students: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33:1025–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MR, Hustad JTP. Personality and alcohol-related outcomes among mandated college students: Descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and college-related alcohol beliefs as mediators. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:879–884. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MR, Kite BA, Henson JM. Unique direct and indirect effects of impulsivity on alcohol-related outcomes via protective behavioral strategies. Journal of Drug Education. 2012;42:425–446. doi: 10.2190/DE.42.4.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince MA, Carey KB, Maisto SA. Protective behavioral strategies for reducing alcohol involvement: A review of the methodological issues. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:2343–2351. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons JP, Nelson LD, Simonsohn U. False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychological Science. 2011;22:1359–1366. doi: 10.1177/0956797611417632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarnal C, Qian X, Hustad JTP, Sims D. Intervention for positive use of college student leisure time. Journal of College and Character. 2013;14 doi: 10.1515/jcc-2013-0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]