INTRODUCTION

The importance of parents, guardians, and other caregivers (henceforth referred to as “parents,” but inclusive of the adults who function in a parenting role) in all aspects of adolescent development cannot be overstated, but their role in sexual education is crucial. Parents are the single largest influence on their adolescents’ decisions about sex, and parents underestimate the impact they have on their decisions.1 For most parents and their children, the prospect of talking about topics related to sexuality creates anxiety and apprehension, and this may lead to avoidance of discussions (Table 1 provides a list of common sources of anxiety associated with talking about sexuality).

Table 1.

Sources of anxiety for parents and teens when discussing sexuality

| Sources of Anxiety for Parents | Sources of Anxiety for Teens |

|---|---|

Real or perceived ignorance

|

Real or perceived ignorance

|

Saying too much

|

Saying too much

|

Fear of difficult questions

|

Fear of difficult questions

|

Finding out something unknown about child

|

Finding out something unknown about parent

|

Fear of teen’s reaction/perception

|

Fear of parent’s reaction/perception

|

Discomfort with topic

|

Discomfort with topic

|

Parents may also delay conversations about sexuality because they are afraid of putting ideas into their child’s head before they are “ready” or because they equate talking about sexuality with giving tacit permission to explore sexual behaviors. In fact, sex education and parent-child communication about sexuality are associated with delayed sexual activity and more consistent contraceptive use.2–4 Conversations with parents have the potential to become the benchmarks against which teens measure other information about sexuality and serve as a buffer against early sexual activity.

Unfortunately, in many instances, “sex talks” between parents and their children are less than optimal. Parents tend to exclude positive topics associated with sexuality, such as pleasure, love, and healthy relationships, in favor of negative topics and warnings. These conversations lacking positive topics associated with sexuality, pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and abuse and exploitation. Parental guidance is needed as adolescents develop, but parents need to have accurate and complete information from medically accurate resources to share with their teens. The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of the best practices, specific tips, and resources that health care providers can use to empower parents.

Parents Talking with Adolescents About Sexuality: Best Practices

This article is an overview of currently understood best practices related to talking to adolescents about sexuality within the context of contemporary knowledge and broad cultural norms. For the sake of brevity, the authors describe the best practices in relation to major topics in sexuality.

Talking about sexuality, in general

The groundwork for communication about sexuality is laid in early childhood and takes place over the course of many interactions and “teachable moments” — opportunities that arise to start a conversation or provide information about a topic—as opposed to one “big talk” about “the birds and the bees.” Regular and ongoing discussions support and reinforce concepts addressed in earlier conversations and increase the likelihood the child will encode the content to memory and have it cognitively accessible later. Some parents and teens may have discussed sexuality in the past but have not done so recently. An absence of conversation may be an indicator that it is time for parents to check in with their teen.

When it comes to conversations about sexuality, parents may have different ideas about what constitutes a “conversation” than their children. Parents report more frequent communication about sex than their teens, in part because they consider a wider array of topics to be sex-related than teens, including generalized warnings indirectly related to sex, such as “Stay away from boys. Period.”5 Some parents may defer to these blanket warnings because they do not know where to begin or how to be more specific. In order to prepare parents for what to expect and where to start, Table 2 highlights what children and adolescents tend to know and ask about concerning sexuality across their development. Box 1 suggests teachable moments when parents may want to consider having a conversation related to sexuality.

Table 2.

What kids know and what questions parents can expect from their children across adolescence

| Age Range | What Kids Know | Questions to Expect |

|---|---|---|

| 7–10 y (preadolescence) |

|

Physical development and how they compare to others (what’s “normal”). Some girls will begin puberty or menstruation at this age and should be prepared by their parents. Examples include:

|

| 11–12 y (early adolescence) |

|

Sex education in school starts around 5th or 6th grade. Parents should allow their children to participate and continue the conversation at home. Questions may focus on the mechanics of sex and pregnancy:

|

| 13–14 y (early midadolescence) |

|

Most girls will have begun menstruation, and most boys will be experiencing erections. Teens will have questions related to sex and pregnancy:

|

| 15–16 y (late midadolescence) |

|

Approximately 15% of teens begin having sex by the age of 15.5 More questions will focus on the risk of various activities for pregnancy or STIs and prevention.

|

| 17–18 + years (late adolescence) |

|

About 50% of teens begin having sex between the ages of 17 and 185 and likely experience intense physical and emotional attraction to their partners or potential partners. Questions may arise around romantic love:

|

Box 1. Examples of teachable moments related to sexuality.

From the mass media

News coverage of a case related to rape, sexual abuse, and so forth

Shared media experiences (television, movie, YouTube, music, and so forth) depicting a romantic or sexual situation, such as portrayal of 2 people going on a date, or a gay/ lesbian couple, transgender people

Portrayals of men and women in advertisements

Portrayals of transgender people in the media

Celebrity coverage of almost anything

From social media

Mentions of body weight/size/judgments in pictures and picture comments (eg, thigh gaps, statements related to looking fat or skinny)

Idealized and sexualized images

Bullying and sexual harassment

Posts from the “It Gets Better” campaign

Sexting and/or other social media issues

Major life events or developments

Pregnancy, miscarriage, birth, or adoption in the family or friends

A friend or family member “coming out” as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and so forth

Menarche

Everyday occurrences

A pet giving birth or laying eggs

Overhearing the use of sexual slurs, such as fag, whore, slut, and so forth

Expressions of affection between people in public or semipublic places

Family media sharing or meal conversations

Topics covered when talking about sexuality

Many parents focus on providing factual and mechanical information about sex and neglect discussion of emotions, sexual pleasure, and values. There is likely a fear that portraying sex in too positive a light may entice and encourage experimentation. Parents may need help understanding that conversations about sexuality can be factual and sex positive while simultaneously communicating boundaries and values. These conversations are opportune times for parents to relate their values and expectations in relation to their child’s behavior. For example, “If you have sex, we believe it is important to use a condom for your health and safety. Condoms help prevent STIs and unintended pregnancy.” When appropriate, parents may want to share decisions that they may have regretted in their own teen years and discuss how they might have handled situations differently.

Anatomy/physiology

Parents should begin teaching children age-appropriate words for body parts and their functions at an early age. There are several excellent books for children and teens that model age-appropriate terminology (Table 3).6 There is increasing evidence that using anatomically correct words—such as penis, scrotum, vagina, and vulva—is beneficial to children’s early development of body confidence, self-empowerment, and safety.7,8 Many parents feel more comfortable teaching their children generic, playful, or distracting words to identify their anatomy. There is some concern that the use of euphemisms sends the message that these parts are embarrassing, secret, or shameful. Using common names for these parts facilitates conversations about how to keep them healthy, clean, and safe. Speaking comfortably about these topics early on will help children express concerns about health, illness, relationships, sex, shaming, exploitation, or abuse in the future.

Table 3.

Resources for providers, parents, and adolescents

| Resource | Contact Information/Web Site | Description/Useful Features |

|---|---|---|

| Advocates for Youth | (202) 347-5700 AdvocatesForYouth.org | Works in both the United States and abroad to promote sexual health education and services for youth. Web site includes resources, continuing education opportunities, and curricula for sex educators |

| American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) | AAPorg HealthyChildren.org BrightFutures.aap.org |

Professional guidelines and standards for pediatric care. Specific useful resources:

|

| American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) | ACOG.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Adolescent-Health-Care | Information and resources for adolescent sexuality and sex education |

| American Sexual Health Association (ASHA) | (919) 361-8400 ASHASexualHealth.org IWannaKnow.org |

Organization advocating for sexual health education and policy to promote sexual health. Web site includes especially good information for teens, including suggested questions to ask a health care provider about sex |

| Answer: sex ed, honestly | answer.rutgers.edu | Provides training and education to teachers and other youthserving professionals. Web site also includes resources for parents and teens |

| Bedsider & Bedsider Provider (a program by The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy) | Bedsider.org Providers.Bedsider.org |

Bedsider: An online birth control support network that includes a hotline for free birth control information and e-mail or text reminders for birth control, appointments, prescription refills, and gonorrhea and chlamydia retests Bedsider provider: Resources to offer patients, frequently asked questions for providers, and “Shoptalk”: currents events, updates, and featured resources in the world of reproductive health care practice and research |

| Boston Children’s Hospital | YoungMensHealthSite.org YoungWomensHealth.org |

Provides medically accurate information, educational programs, and conferences about many health topics, including sex |

| The Center for Sex Education (CSE) | (973) 387-5161 SexEdCenter.org | An organization within Planned Parenthood that writes and publishes resources on sex education. Includes an online bookstore (www.sexedstore.com) with books, curricula, and training manuals for sex educators and parents. CSE sells several books authored by Robie H. Harris recommended within this article |

| The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) | (404) 639-3311 CDC.gov | US federal agency that works to promote health, prevention, and preparedness activities in the United States and worldwide. Includes a useful tip sheet for talking with parents about the HPV vaccine (referenced within this article) at http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/who/teens/for-hcp.html |

| Center for Parent Information and Resources | ParentCenterHub.org | Information for parents and teachers about sexual education for students with disabilities, including specific disabilities, such as autism spectrum disorders, cerebral palsy, and spina bifida |

| Futures Without Violence | FuturesWithoutViolence.org | Organization focused on ending domestic and sexual violence. Provides free resource cards (in large quantities, if necessary) containing screening questions for IPV in adolescents |

| Go Ask Alice! (from Columbia University) | GoAskAlice.columbia.edu | Provides questions and answers on a variety of health topics, including sexual health. Maintains a large question and answer library and accepts new questions |

| IMPACT on Health and Wellness (an initiative by the Maternal Child and Health Bureau of US Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS]) | Family Voices, Inc Phone (505) 872-4774 or (888) 835-5669 fv-impact.org/ | Information and resources promoting maternal and child health including The Well Visit Planner—an online tool to help families prepare for their upcoming well-child visits (available in English and Spanish) |

| KidsHealth (by Nemours) | KidsHealth.org | Provides health information about kids and teens that is free of “doctor speak” |

| The Mediatrician | http://cmch.tv/parents/askthemediatrician/ | A Web site where a pediatrician offers research-based information and advice to parents about their children’s media use and its implications for their health and wellness |

| The National Campaign to Prevent Teen And Unplanned Pregnancy | (202) 478-8500 TeenPregnancy.org |

An organization providing national and state statistics on teen pregnancy, poll results, and analyses of factors affecting sex education and teen sexual behavior and contractive use. Promotes teen sexual health through initiatives such as Bedsider and Bedsider Provider |

| North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology (NASPAG) | (856) 423-3064 E-mail: hq@naspag.org NASPAG.org |

Professional organization devoted to promoting research and education related to gynecologic care in youth; holds an annual meeting |

| Office of Adolescent Health | (240) 453-2846 http://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/ |

Department within the US DHHS that funds research and interventions to reduce unplanned pregnancy and STIs in adolescents. Maintains a list of Evidence-Based Programs (EBPs) for pregnancy and STIs and a list of federal resources (tip sheets, fact sheets, treatment guidelines, and so forth) for adolescent health, including reproductive health |

| Parent Advocacy Coalition for Educational Rights (PACER) | (952) 838-9000 1-800-537-2237 Pacer.org |

Training, information, and resource center for families of youth with disabilities—includes sexuality |

| PFLAG (formerly known as Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays) | PFLAG.org | Advocates for gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered people and their families |

| Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA) | (212) 541-7800 PlannedParenthood.org |

Provider and advocate for reproductive health care and education across the United States |

| Scarleteen | Scarleteen.com | Highest-ranked Web site for sex education and sexuality advice; read by youth 15–25 |

| Sex, Etc. | Sexetc.org | Magazine and Web site offering sexual education and health information to teens. Includes material written by teens, forums for discussion, sexual health videos, blogs on current events, a state-by-state guide to teen rights in sex education, birth control, and health care |

| Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS) | (212) 819-9770 siecus.org | Organization that provides policy, community action, and research updates on hot-button issues related to sexuality and sexuality education. Has a free toolkit for providers: PrEP Education for Youth-Serving Primary Care Providers Toolkit |

| Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine (SAHM) | AdolescentHealth.org THRIVE app | Multidisciplinary professional organization promoting adolescent health through advocacy, clinical care, health promotion, professional development, and research. Holds an annual meeting |

| Urban Dictionary, LLC | UrbanDictionary.com | This is “the” Web site to look up slang words and phrases. The contents are crowd sourced and continuously updated- especially sex-related slang- useful for parents trying to interpret mass media and social media their child is exposed to, such as common expressions, slang words, and acronyms |

| Your Child Development and Behavioral Resources | www.med.umich.edu/yourchild/ Web site for materials, resources, and useful Web sites for families of youth with disabilities— includes sexuality education resources | |

Puberty

As the child approaches the preteen years, parents should begin talking to them about puberty and what it means for their physical appearance, feelings, and reproductive ability. The “prepuberty years”—when some children begin the pubertal maturation process—begins as early as primary school. In a second grade class, it is likely that some girls have begun to develop body odor, breasts, pubic hair, and height. Changes in some boys may start in the next few grades, and understanding the process enough to be respectful and supportive of others is part of this conversation.

Masturbation

Masturbation is a frequently neglected topic because of the potential for discomfort, embarrassment, and widespread misinformation, but teens need to understand that masturbation is normal and healthy. It can provide an outlet for sexual urges that carries no risk of pregnancy or STIs. It can be self-soothing and calming. In addition to reassuring teens that masturbation is a healthy part of sexuality, parents should communicate the appropriate times and places for engagement in this behavior.

Oral sex and anal sex

Many parents do not discuss oral and anal sex specifically with their adolescents. As a result, teens are largely unaware of the risks associated with oral and anal sex. Many teens will engage in one or both of these behaviors to avoid pregnancy but inadvertently put themselves at risk for disease—especially if barrier protection is not used. Parents should educate themselves and their teens regarding barrier methods of prevention, how to use them correctly, and how to obtain them. Purchasing condoms, and keeping them in an accessible place, can be a powerful conversation opener, and in some communities is considered a normative part of parenting an adolescent.

Abstinence

Many parents want to present teens with abstinence as their only option when it comes to sexual behavior. Although teens have times when they are abstinent, it is not an effective life-long plan. Parents may encourage abstinence and share their values around their support, but this strategy is not advised in isolation. Parents should teach that it is the only 100% effective way to avoid pregnancy and disease, but also how to protect themselves if they become sexually active. Research shows that adolescents with abstinence-only sexual education are no more likely to abstain from sex than adolescents who received no sexual education at all.9

Harm reduction

Most adolescents classify sexual behaviors as “safe” or “unsafe” and fail to appreciate the concept of relative risk.10 Pediatric providers can teach parents and teens to think of sexual behaviors along a continuum from “less risky” to “very risky” and encourage parents to suggest ways to achieve sexual pleasure with a partner that involve less risk than intercourse, such as hugging, kissing, mutual masturbation, and oral sex. Some parents may balk at the idea of encouraging these “less risky” behaviors, but providing them with a more nuanced understanding of risk minimization strategies can protect their teen’s health.

Prevention

Prevention is multifaceted, and risk factors for a host of unwanted or consequential health outcomes in adolescents are interrelated. Prevention efforts come in many forms, and parents can enhance prevention of a variety of negative outcomes and enhance their child’s overall health promotion by

Increasing communication and positive family interactions;

Being involved in their school and homework;

Setting clear boundaries and providing consistent and caring discipline;

Monitoring their behavior, including their activities, engagement, interests, and online participation;

Getting to know their friends;

Identifying teachable moments related to sex, gender, identity, sexual orientation, relationships, decision making, sexual behavior, contraception, and life goals;

Encouraging good health practices, including diet, sleep, and exercise;

Teaching healthy ways to cope with stress, anxiety, and negative events;

Scheduling appointments with a pediatric provider regularly for age-appropriate care;

Communicating about sexuality, including facts, values, and expectations;

Educating about protections from STIs and unwanted pregnancy;

Encouraging involvement in school and community activities;

Engaging with schools, community programs, and faith-based organizations providing sexual health education to youth to discuss whether the information provided is comprehensive, medically accurate, and evidence-based; and

Urging local, state, and national support for comprehensive sex education and other health promotion and services for youth by communicating these needs to political officials and by voting for candidates who support these issues.

Vaccination

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that all children ages 11 and 12 should be vaccinated against human papillomavirus (HPV) and provides tip sheets for talking to parents about the HPV vaccine (see Table 3). HPV can be transmitted through a variety of intimate activities involving contact with genitalia, mucous membranes, or bodily fluids even if the infected person has no signs or symptoms. Early vaccination is optimal but recommended (see Diane R. Blake and Amy B. Middlemans’ article, “HPV Vaccine Update,” in this issue).

Reproductive health care

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) encourages anticipatory guidance of adolescents in relation to sex beginning at 11 years of age, and parents should begin a dialogue with their child about sexuality at this time if they have not already done so. All adolescents should receive information from their health care providers and parents about where and when to seek reproductive health care and screenings—including locations other than their regular providers, such as free health clinics, county health departments, and the family planning centers. The AAP recently released a clinical report on sexuality education11 that reinforces the importance of the pediatrician’s role in communicating evidence-based reproductive health and sexuality education and suggests additional resources (included in Table 3).

Connectedness with adults who care

Parents are crucial to a child’s healthy development, but a supportive, caring relationship with any responsible adult-parent/step-parent, another family member, or friend, teacher, coach, or other-is the most important factor in the development of resilience and avoidance of negative outcomes.12,13 The ability to adapt to and cope with adversity comes from a network of relationships with trusted adults to create a protective buffer and developmental “scaffolding” that allows children to adapt to adversity and thrive.

Engagement with activities and interests

Overall, involvement with activities and interests promotes positive development. There is some paradoxic evidence when it comes to sports participation, however. Girls’ involvement in sports is associated with decreased risky sexual behavior, whereas boys’ involvement in sports is associated with increased risky sexual behavior.14 Sports involvement for girls may increase self-confidence and self-esteem and help them resist traditional gender roles that girls should be sexy, powerless, and compliant. Sports involvement for boys, on the other hand, may be associated with boys subscribing to the traditional role of men. Boys should be encouraged to participate in sports for the benefits, but need to be “inoculated” against stereotypical male gender ideology and behaviors through conversations with parents and other trusted adults about more egalitarian gender roles.

Romantic relationships

Navigating their adolescents’ early romantic relationships can be challenging for parents. Adolescents begin experiencing the overpowering emotion of falling in love. This can be problematic because of the lack of emotional regulation and the tendency for relationships at this age to be short term (weeks for younger adolescents, months for middle adolescents, and years for older adolescents and young adults). The emotional intensity involved with falling in love, maintaining a relationship, and breaking up within a short period of time can create a wild ride on an emotional roller coaster. Teens will need guidance as they learn to manage the endings of relationships, a key developmental task.

In addition to emotional risk, adolescent relationships come with other risks. An ongoing intimate relationship with a partner, for example, may put adolescents at increased risk of STIs and unwanted pregnancies, because condom use consistency diminishes with duration of relationships.15 Teens want to communicate trust and fidelity to their partners, and condom use often diminishes. Parents should watch for and discuss warning signs of current or potential Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) from romantic partners. They should ask questions about whether a partner respects their choices, gives them time and space to spend time with friends, or pressures them to do things they do not want to do (see Futures Without Violence in Table 3).

Sexual orientation

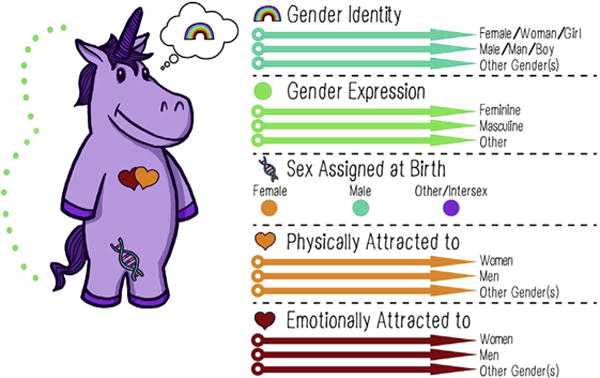

A thorough discussion of parent-child communication about sexual orientation is beyond the scope of this article, and sexual orientation, specifically, is addressed in a separate future issue of this journal. Parents are encouraged to approach conversations with their children about sexual orientation with an open mind and to listen more than they speak. “The Gender Unicorn” in Fig. 1 is a helpful framework to understand the sexual identity spectrum and to establish a common language around gender identity, gender expression, biological sex, and sexual orientation.

Fig. 1.

The gender unicorn. (Design by Landyn Pan and Anna Moore. Trans Student Educational Resources. To learn more, go to: www.transstudent.org/gender.)

Many parents make the mistake of thinking LGBTQIA (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual) adolescents do not need information on pregnancy prevention because they may not be engaging in sexual behavior with an opposite sex partner, but LGBTQIA adolescents sometimes engage in heterosexual behaviors. There are risks for STIs regardless of the sex of the partner they choose. LGBTQIA teens should receive resources and information about barrier protection as well as ongoing and emergency contraception. Parents of LGBTQIA children and adolescents can seek out supportive groups and resources such as PFLAG (see Table 3).

Contraception

Parents will want to review the types of contraception available. Even if parents are encouraging abstinence, teens need to know how contraceptives work and their effectiveness. A well-informed teen is a valuable resource for their peers. Table 3 suggests resources for medically accurate contraceptive information for providers, parents, and teens (related articles in this issue offer additional guidance).

Media/pornography

Personal portable devices such as smartphones and tablets are increasingly the source of teen’s media access, including communication with words, photos, and videos. Images related to sex and alcohol are prevalent, and exposure increases the likelihood of risky sexual attitudes and behaviors.16,17 Parents should be aware of their child’s media consumption, although advances in technology make it increasingly difficult to keep track. “Spot checks” on teen’s smartphones and other devices can be conducted, but on some apps (eg, Snapchat) images are only stored temporarily, and it is nearly impossible to know where the user has been. Although it is beyond the scope of this article, a continuing challenge for parents will be to keep up with technological advancements that allow parental monitoring and control of media exposure on personal devices. Parents will also need to have conversations with their teens about interpersonal communication (eg, sexting), how alcohol and other substances affect decision making, portrayals of men and women in the media, and issues related to consent and power in relationships. One recommended resource in Table 3 is “Ask the Mediatrician,” a pediatrician who specializes in the effects of media exposure on children and adolescents. Parents can use this tool for entry points into conversations and send questions to be answered.

Sexual abuse/exploitation

Parents should closely monitor who interacts with their children and the nature of this relationship. Many parent-child conversations about abuse and abduction prevention focus on unknown strangers, but most abusers are known to the children they abuse. Parents should explain abuse totheir children from an early age. This explanation should include teaching that only those people who are helping them keep their bodies healthy, clean, or safe are allowed to touch them. Excellent books containing age-appropriate language explaining abuse include those authored by Robie H. Harris (see Table 3). Abuse is not the only danger to adolescents; they are vulnerable to a host of exploitive relationships whose symptoms and consequences may be more subtle. Parents should closely monitor their teens’ activities and companions and ask questions.

Concrete Tips for Parents for Talking to Adolescents About Sexuality

In light of the best practices for parent-adolescent communication presented, the authors offer concrete tips for parents to help them focus their efforts:

Educate yourself first. Ask your provider for resources. Explore them.

Consider your own emotions and values and what it is important for you to transmit.

Establish a common language for talking about sexuality and create conversational ground rules to foster a nonjudgmental atmosphere.

Be clear and candid and admit when you do not know the answer. Working together to find answers may be rewarding. It is always okay to say, “I don’t know” or “I need to think about that.”

Use teachable moments to have conversations related to a variety of topics on a regular basis. Teachable moments include major life events and everyday occurrences, and they can be spontaneous or scripted in advance.

Solicit the help of close family and/or friends who may be trusted adults for your child. It is beneficial to have a network of supportive and “askable” adults.

Pay attention to what your child is seeing and hearing in the media (television, movies, video games, social media posts, music, and so forth). Monitor social media use and limit Internet access to common family spaces as much as possible. Take advantage of the many teachable moments in the media.

Know who is providing sex education to your child and whether the educational content is comprehensive, medically accurate, and evidence based. Be a proponent of comprehensive sex education in your schools and faith-based or community organizations.

Identify and communicate about organizations, clinics, and resources in the community that provide access to reproductive health care.

Check in regularly about what your child is feeling, seeing, hearing, and experiencing. Listen. Share your own experiences, successes, and mistakes.

Understand that what you do is the most important message about your values.

SUMMARY

Parents should offer clear, accurate, and developmentally appropriate information about the behaviors expected from their children and how to keep them safe. Parents play a primary role in disseminating sexual information-through words, behaviors, and values they convey. The role of the of the health care provider is to advise parents and direct them to resources so they can approach conversations prepared with knowledge and confidence-to make them “askable” parents. Health care providers have a responsibility to independently and collaboratively address issues with their adolescent patients, respecting standards of confidentiality, in a framework that also includes state-specific child protection mandates. The strategies and resources recommended in this article are intended to help providers guide both parents and adolescents to improve their knowledge of and communication about sexuality matters.

KEY POINTS.

Parents are an influential source of information about sexuality to their adolescents and have the ability to shape these values and behaviors.

Parents should communicate comprehensive, medically accurate information to their teens.

Parents should incorporate discussions about positive aspects of sexuality, such as pleasure, satisfaction, and intimacy, into these conversations.

There are resources available for providers, parents, and teens for information, guidance, and support, and the major ones are highlighted here.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Melissa Keyes-DiGioia, CSE, for her insightful comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Footnotes

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.The National Campaign. Teens say parents most influence their decisions about sex: new survey data of teens and adults released [press release] Washington, DC: 2012. Available at: https://thenationalcampaign.org/press-release/teens-say-parents-most-influence-their-decisions-about-sex. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karofsky PS, Zeng L, Kosorok MR. Relationship between adolescent-parental communication and initiation of first intercourse by adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28(1):41–5. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller KS, Levin ML, Whitaker DJ, et al. Patterns of condom use among adolescents: the impact of mother-adolescent communication. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(10):1542–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.10.1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinman ML, Small E, Buzi RS, et al. Risk factors, parental communication, self and peers’ beliefs as predictors of condom use among female adolescents attending family planning clinics. Child Adolesc Social Work J. 2008;25:157. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashcraft AM. A qualitative investigation of urban African American mother/ daughter communication about relationships and sex [unpublished doctoral dissertation] Richmond (VA): Virginia Commonwealth University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris RH, Emberley M. It’s perfectly normal: changing bodies, growing up, sex, and sexual health. Somerville (MA): Candlewick Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buni C. The case for teaching kids ‘vagina,’ ‘penis,’ and ‘vulva’. Atlantic. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burger N. Why teaching children anatomically correct words matters. KevinMD.com. 2014 Available at: http://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2014/12/teaching-anatomically-correct-words-matters.html. Accessed July 23, 2014.

- 9.Trenholm C, Devaney B, Fortson K, et al. Impacts of four title V, section 510 abstinence education programs. Princeton (NJ): Mathematica Policy Research; p. 2007. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/impacts-four-title-v-section-510-abstinence-education-programs. Accessed August 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downs JS. Prescriptive scientific narratives for communicating usable science. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(Suppl 4):13627–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317502111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruener CC, Mattson G, Committee on Adolescence et al. Sexuality education for children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20161348. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278(10):823–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, et al. Parent-child connectedness and behavioral and emotional health among adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(1):59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tracy AJ, Erkut S. Gender and race patterns in the pathways from sports participation to self-esteem. Sociol Perspect. 2002;45(4):445–66. doi: 10.1525/sop.2002.45.4.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortenberry JD, Tu W, Harezlak J, et al. Condom use as a function of time in new and established adolescent sexual relationships. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(2):211–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bailin A, Milanaik R, Adesman A. Health implications of new age technologies for adolescents: a review of the research. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2014;26(5):605–19. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreno MA, Whitehill JM. Influence of social media on alcohol use in adolescents and young adults. Alcohol Res. 2014;36(1):91–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]