Abstract

A description of the characteristics of an excellent endoscopy trainer is provided. These characteristics are presented in an accessible format for endoscopy trainers to use to develop their endoscopy teaching. Excellent endoscopy teaching is a fundamental part of providing a high quality, motivated endoscopy workforce.

Background

Endoscopy is a widely used diagnostic and therapeutic tool within medicine. It is performed by a variety of specialists, including gastroenterologists, surgeons and nurses. Endoscopists invariably have trainees to teach. There has been little research into the characteristics of an endoscopy trainer. The existing literature is based on expert opinion1–8 or consensus of groups of individuals.9 10 Two qualitative studies, which explored the process of endoscopy teaching, provide an insight into the characteristics of an endoscopy trainer.11 12 All of these papers are largely atheoretical and at best provide simply a list of trainer characteristics. As such there is only limited knowledge available in the literature about how to teach endoscopy.

Although there are many excellent endoscopy trainers there is evidence that endoscopy teaching could be improved in the UK.13 The national endoscopy training programme provides ‘training the trainer’s courses’ which many trainers have attended.14 These courses are based on the skills teaching models developed by Peyton.15 Beyond these courses there is no formal support structure for trainers to develop their teaching skills. A system to assist trainers to improve their teaching, consisting of a trainer’s handbook, a ‘direct observation of teaching skills’ form16 and a trainer portfolio are under development.

This article is intended to help busy endoscopists to become more effective teachers and stimulate interest in this important area. It provides a description of the characteristics of an excellent endoscopy trainer that have been sorted into an accessible format. These characteristics have been developed from the existing literature and from data generated through interviews with members of four stakeholder groups in the endoscopy community (training leads at endoscopy training centres, consultant trainers, medical trainees and nurse endoscopists). These data were analysed using rigorous qualitative methods. The knowledge can be utilised by an endoscopy trainer in their everyday teaching practice to help increase their teaching effectiveness.

Endoscopy teaching

Endoscopy cannot be taught over a couple of lessons and even the best trainees require a period of time to learn and develop independent practice. A trainer therefore needs to conceptualise training in terms of the individual lesson (or endoscopy list) and the longer term. It is important that each lesson is incorporated into this long term plan so that the goal of independent practice for the trainee can be achieved in the most efficient manner. The hallmark of endoscopy learning is one to one tuition. A trainee may have more than one trainer. Without long term goals there is a danger that each list (or lesson) can be disjointed from the others. Communication among the various trainers teaching an individual trainee is important to ensure continuity. A nominated trainer from the pool should take responsibility for the long term learning of each individual trainee whereas any of the trainers could deliver each individual lesson.

Teaching needs to be personalised to each trainee. Each trainee is an individual and will learn in a different way and at a different pace to their colleagues. A trainer should adapt the training accordingly and not teach every trainee in exactly the same way.

Typically over a period of time a trainee will gradually need less and less input from their trainer. Initially they require a lot of support and guidance and the trainer may need to take over the scope. As they develop they are capable of performing more of the procedure alone and the trainer is required to intervene less often. A trainer may only need to intervene if the trainee is struggling or tackling a new aspect of endoscopy (such as polypectomy). It is therefore vital that the trainer adapts the quantity and quality of teaching to a level appropriate to the individual trainee, at the specific point of time and to the problem being taught.

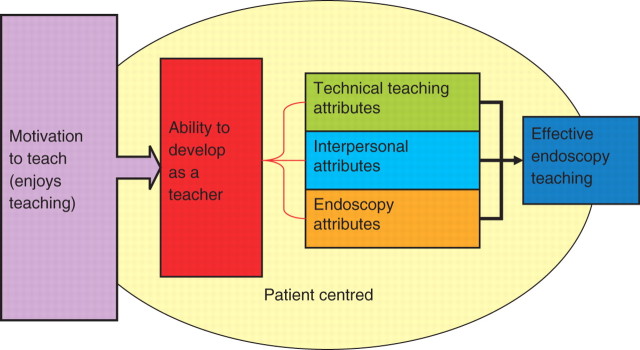

The endoscopy trainer characteristics (or attributes) described in this article are applicable to the individual lesson, the longer term learning or both. A trainer needs the versatility to be able to call upon these characteristics when appropriate and the ability to adapt to the individual situation. The characteristics are divided into six domains, which are as follows:

Interpersonal attributes

Endoscopy attributes

Technical teaching attributes

Developing as a teacher attributes

Motivation to teach

Patient centred

The domains are interlinked as shown in figure 1. The first three domains are necessary to be able to directly deliver effective endoscopy teaching while the latter three are needed to ensure excellence is maintained.

Figure 1.

The attribute domains of an excellent endoscopy teacher.

All of the characteristics of an excellent endoscopy teacher can be learnt. Any endoscopy trainer can use this article as a basis for his or her own development as an endoscopy trainer.

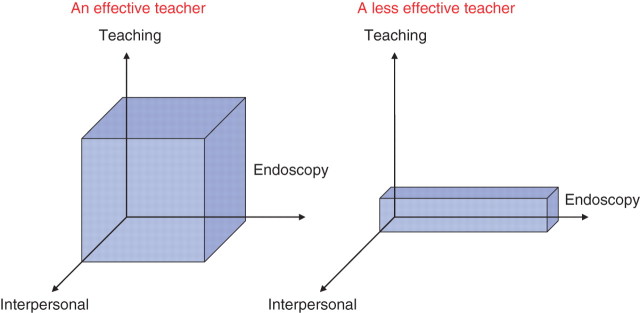

An effective endoscopy trainer

An effective endoscopy trainer is more than simply a good endoscopist. Although endoscopy skills are important, an excellent trainer also needs attributes from two other domains. They need interpersonal and technical teaching attributes as well as endoscopy attributes. A teacher is only effective when she or he has all three. This is shown in figure 2 where the volume of the box indicates the trainer’s effectiveness as a trainer. The endoscopist on the left is a more effective trainer (large volume of blue box) than the endoscopist on the right (smaller volume of blue box), despite the trainer on the right being a better endoscopist. The individual attributes from within these domains are described in the following sections.

Figure 2.

Effectiveness as an endoscopy trainer.

Interpersonal attributes: creating the learning atmosphere

Most trainees who learn endoscopy are experienced professionals practising at a high level within their existing roles. It can be intimidating when starting to learn endoscopy. Endoscopy is completely new to them and they suddenly become complete novices. As such they need to learn in a safe environment that acknowledges their potential anxieties and respects their professional standing. An excellent trainer can help create the appropriate learning atmosphere to do this. The trainer can do the following to create the optimal learning atmosphere for the trainee.

-

■

Make the trainee feel welcome and part of the endoscopy process.

-

■

Be honest with the trainee.

-

■

Respect the trainee as a learner and a professional.

-

■

Be approachable and open so that the trainee feels safe asking questions.

-

■

Show confidence in the trainee to give them self-belief.

-

■

Teach in a patient and calm manner.

-

■

Have realistic expectations of the trainee.

-

■

Get to know the trainee personally, such as family and career goals.

Although every trainee is different, a trainer can improve the learning environment using the above. The trainer can adapt her or his interpersonal behaviour, according to the individual trainee, as their training relationship develops.

Endoscopy attributes: having the knowledge and skills that need to be imparted to the trainee

An endoscopy trainer needs to be proficient in any endoscopic procedure that she or he teaches to others. As such they should perform at least at the minimum level outlined for competence by the JAG and be able to demonstrate their competence through audit data. For example, if they are teaching a trainee colonoscopy, they should have a greater than 90% caecal intubation rate, a greater than 10% polyp detection rate, a serious complication rate of less than 0.5% and appropriate sedation rates.17 If a trainer is not achieving these minimum standards of performance, they should seek additional training from their peers or attend a refresher training course through the national endoscopy training scheme.14 The ability to perform endoscopy is critical as there are instances during endoscopy teaching where a trainer needs to take over the scope to progress the examination.

Furthermore, a trainer must be able to deal with any complications that may arise during endoscopy training. This allows them to both support a trainee who is unfortunate enough to cause a complication and to manage the complication itself. This ability is partly gained through experience.

As well as being able to perform the procedure, the trainer needs an understanding of endoscopy. This understanding allows the trainer to be explicitly aware of how and why particular manoeuvres are successful. For example, in colonoscopy, resolution of a sigmoid alpha loop requires simultaneous clockwise torque, withdrawal and accurate tip steering with the right/left and up/down wheels to maintain a luminal view. An expert will do all these manoeuvres implicitly. It is only when the trainer becomes explicitly aware of what he is doing that he or she can teach it to others. This has been termed ‘conscious competence’.15 This conscious competence allows a trainer to be able to describe, in a comprehensible way to her or his trainee, how to perform the manoeuvres needed to carry out a successful endoscopy.

A trainer can improve their conscious competence by actively asking themselves during their own endoscopy service lists exactly what they are doing. Initially this may slow down their endoscopy lists but investment will be rewarding in the long run by giving the endoscopist a deeper understanding of endoscopy and how exactly they are controlling the endoscope. The acquisition of conscious competence can be helped by using a three dimensional imager (for colonoscopy—if available) or referring to an endoscopy textbook, such as that by Cotton and Williams.18

Teaching attributes: transferring knowledge and skills to the trainee

Endoscopy teaching can be divided into three parts: (1) preparation, (2) actual delivery of the teaching and (3) feedback following the procedure. These can be applied to both long term teaching and also each individual list or lesson.

Long term teaching

- Preparation

-

■Establish the trainee’s current level of competency through discussion with the trainee and observation of performance.

-

■Agree this level with the trainee.

-

■Agree learning goals with the trainee for the next block of teaching so as to build on existing competencies.

-

■Provide enough lists containing appropriate cases for the trainee to achieve these goals.

-

■Limit the number of trainees each trainer is teaching to a level that is manageable.

-

■

- Delivery of teaching

-

■Use a mix of endoscopy lists, simulation, books and e-resources to help the trainee meet their learning goals.

-

■Ensure that the trainee collects performance data, in the form of DOPS, completion rates and complications.

-

■Be available so that the trainee can discuss their learning at opportune moments.

-

■

- Feedback

-

■Assess if the trainee has achieved her or his long term learning goals.

-

■Review the training and adapt future training to overcome any shortcomings.

-

■

Pendleton’s rules for giving feedback (adapted from Pendleton et al19).

Ask the trainee to identify aspects of her or his performance that went well.

Reinforce these points and add other aspects that the trainee may have missed.

Ask the trainee to identify aspects of their performance that could be improved.

Reiterate these aspects and also highlight aspects they did not identify that could be improved.

Summarise and identify how the trainee can improve in the next case or list.

Feedback is a fundamental element of excellent teaching. It can be delivered in a formal structure, such as that described by Pendleton et al,19 or in an informal manner bespoke to the trainee. How a trainer delivers feedback will change depending on the trainee, the trainee’s current level of performance and how well they know the trainee. The five step process (see box) is a useful framework to use with a new trainee or for a trainer new to giving feedback. This can be adapted as the training relationship develops.

Teaching over a single list (or procedure)

- Preparation

-

■Define the roles of each member of the endoscopy team during the training encounter; the nurses must know that a list will be a training list.

-

■Agree ground rules with the trainee.

-

■Agree a common vocabulary with the trainee.

-

■Agree SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timely) goals with the trainee for the session.

-

■Populate the list with appropriate cases for the trainee.

-

■

- Delivery of teaching

-

■Be available for the trainee.

-

■Teach only one thing at a time so as not to overburden the trainee.

-

■Reinforce and build on existing competencies.

-

■Intervene in a timely fashion if the trainee is not making progress.

-

■Deal with any mistakes made by the trainee.

-

■Closely observe the whole room (trainee, patient, screen, nurses) to be aware of what the trainee is doing.

-

■Use a mix of suggestions, prompts, solutions, explanations, reassurance, challenge and instructions to help the trainee when appropriate.12

-

■Teach in a style and pace suited to the individual trainee.

-

■Intervene proportional to the competence of the trainee and the difficulty of the procedure.

-

■Adjust position in the room to meet the needs of the trainer (standing closer with a junior trainee or if a trainee is struggling).

-

■Help the trainee to assimilate all the available information (from screen, feel of scope, comfort of patient and nurses) to help them progress.

-

■Adjust the quantity of dialogue to the trainee and the specific problem being learnt, bearing in mind that ‘less is usually more’, do not overburden the trainee.

-

■Provide the trainee with opportunities to speak and actively listen.

-

■Check that the trainee understands what has been said.

-

■Ask a trainee to verbally run through specific manoeuvres before they physically do it—this mental rehearsal can often identify gaps in knowledge or process.

-

■Be aware of non-verbal communication and use it constructively.

-

■Give the trainee enough time to carry out the procedure, do not rush them.

-

■Allow the trainee to make mistakes, provided the patient is not put at risk.

-

■Hand back the scope once any difficulty has been passed.

-

■

- Feedback: allowing the trainee to reflect on their performance

-

■Always provide feedback close to the teaching event

-

■Deliver the feedback in a framework appropriate for the trainee, using a more formal structure initially (see box19).

-

■Help the trainee to reflect on their performance.

-

■Reinforce positive aspects of performance.

-

■Identify with the trainee areas to develop and improve.

-

■Deal with any lack of insight within the trainee.

-

■Review if the goals of the session have been met and set goals for future sessions.

-

■

Developing as a teacher

The characteristics described in the above three domains (interpersonal, teaching and endoscopy) are a means of delivering endoscopy teaching. An excellent teacher will be able to draw on all of these attributes where necessary to optimise the teaching he or she delivers. Teaching excellence however, is not static. An excellent teacher will also strive to be even better. They do this by:

- Evaluating the teaching they have delivered to identify areas that can be improved, through

-

■self-reflection: the attributes quality, motivated endoscopy workforce. described in this article can be used as a basis;

-

■feedback from others, including peers, endoscopy nurses and the actual trainee—opening clear, receptive and non-judgemental lines of communication is important.

-

■

Planning how they are going to overcome any deficiencies in their teaching.

Feeling comfortable as a trainer and confident in their abilities as an endoscopist.

Motivation to teach

Ultimately, a trainer will only be an excellent trainer if they are motivated to teach. They need to have a desire for their trainee to learn and become a good endoscopist and take pride when their trainee gains independence. This motivation, or enthusiasm for teaching, is often inherent but can also be developed through excellent teaching practice, with success breeding the desire for even more success.

Patient centred

Finally, the most important trainer characteristic is to remain patient centred at all times. Ultimately, the majority of endoscopy training is performed on real patients. This is unlikely to change in the near future as simulators do not yet provide a challenging enough platform for comprehensive training. At all times it is imperative that patients are respected, have their dignity maintained and above all are safe during any training.

Summary

This article provides a description of the characteristics of an excellent endoscopy trainer. The characteristics are contained in six domains that are summarised in figure 1. Of course this is only one representation of the characteristics of an excellent endoscopy trainer, there are undoubtedly many innovative practices of teaching that are employed successfully on a routine basis. This conceptualisation however, gives endoscopy trainers a framework against which they can measure their own teaching. Furthermore, it can be used for trainers to develop towards excellent teaching. The conceptualisation described in this article is intended to both encourage innovations as well as provide a basic framework to help trainers to teach well. Excellent teaching is a fundamental component to ensure a high quality, motivated endoscopy workforce. Every trainer has the potential to make a big difference.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Professor Roger Barton, Dr Sally Corbett and Dr Mark Welfare who supervised my MD. They share the intellectual property for the content of this article.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was funded by Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This study was conducted with the approval of the Leeds North Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Sivak MV., Jr The art of endoscopic instruction. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 1995;5:299–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barton R. Learning to teach ERCP—practical tips following a personal revelation. CME J Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 1999;2:93. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teague RH. Can we teach colonoscopic skills? Gastrointest Endosc 2000;51:112–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waye JD. Comment on ‘Can we teach endoscopic skills?’ Gastrointest Endosc 2000;51:114–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waye JD. Teaching basic endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2000;51:375–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balfour TW. Training for colonoscopy. J R Soc Med 2001;94:160–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waye JD, Leicester RJ. Teaching endoscopy in the new millennium. Gastrointest Endosc 2001;54:671–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas-Gibson S, Williams CB. Colonoscopy training—new approaches, old problems. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2005;15: 813–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ASGE. American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy: principles of training in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointes Endosc 1999;49:845–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teague R, Soehendra N, Carr-Locke D, et al. Setting standards for colonoscopic teaching and training. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;17(Suppl):S50–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thuraisingam AI, MacDonald J, Shaw IS. Insights into endoscopy training: a qualitative study of learning experience. Med Teach 2006;28:453–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thuraisingam A, Shenoy A, Anderson J. What are the key components of hands-on colonoscopy training? Gut 2007;56(Suppl II):A103. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells CW, Inglis S, Barton R. Trainees in gastroenterology views on teaching in clinical gastroenterology and endoscopy. Med Teach 2009;31:138–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The National Endoscopy Training Programme. www.jets.nhs.uk (accessed 23 August 2009).

- 15.Peyton J. Teaching and learning in medical practice. Silver Birches: Manticore, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trainer evaluation tool. www.thejag.org.uk/Whoareyou/JAGforconsultants/tabid/58/Default.aspx (accessed 24 August 2009).

- 17.JAG certification requirements. http://www.thejag.org.uk/Portals/0/General%20Forms/JAG%20Certification%20Requirements%2013.08.09.pdf (accessed 24 August 2009).

- 18.Cotton PB, Williams CB. Practical gastrointestinal endoscopy: the fundamentals, 5th Edn Oxford: Blackwell Sciences, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pendleton D, Schofield T, Tate P, et al. Giving feedback. In: The new consultation: developing patient doctor communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003:75–80. [Google Scholar]