Abstract

Parenteral methotrexate is recommended for patients with Crohn's disease who have failed treatment with thiopurines. There is no good evidence for the use of oral methotrexate, yet patients frequently receive this due to the difficulties associated with prescribing and administering an unlicensed, cytotoxic drug.

We present our experience of developing a local service to provide our patients with the option to self-administer parenteral methotrexate in a safe and structured manner at home.

Background

Methotrexate is used as a second-line immunomodulator in patients with Crohn's disease when thiopurine analogues are not tolerated or lack efficacy.1 2 High-level evidence exists for the efficacy of weekly intramuscular (IM) methotrexate injections for inducing and maintaining remission in Crohn's disease.3 Oral preparations of methotrexate are of no proven benefit in Crohn's disease.4 IM injections are not easy to self-administer; however, a study has shown that subcutaneous (SC) methotrexate injections are also effective, well tolerated, and safe in patients with Crohn's disease.5

The Tunbridge Wells Hospital is part of a large acute hospital trust that provides a full range of medical services to around 500 000 people living in southwest Kent and northeast Sussex. In our hospital, the majority of patients who were candidates for parenteral methotrexate opted for the oral preparation of the drug, rather than the inconvenience of weekly visits to the hospital for their injections. This occurred despite advice that the oral preparation of methotrexate was unproven to work.

We wanted to improve the service for local patients by giving them the option to receive the correct preparation of methotrexate in a more convenient manner. A model existed for home methotrexate prescription in the rheumatology unit, and we sought their advice in establishing our own service.

Method

There are a number of considerations that must be taken into account to provide a service whereby patients can self-administer parenteral methotrexate at home safely.

Some private healthcare companies—for example, Healthcare at Home, deliver such a service; however, after consultations with the managers and pharmacy at our hospital, it became clear that it would be more cost-effective to set up the service inhouse, as well as offering a greater degree of autonomy.

Below we describe the problems that we encountered in establishing this service, and the ways in which we resolved them.

Methotrexate is not licensed for use in Crohn's disease

Although there is good evidence for the use of methotrexate in Crohn's disease, it is not licensed for this indication.6 We therefore needed to apply in writing to the local drug and therapeutics committee to obtain permission to prescribe parenteral methotrexate (online appendix 1; standardised forms are available in each trust if requested through pharmacy). This was approved and methotrexate can now be used by the gastroenterologists in our hospital to treat patients with Crohn's disease. Since methotrexate is unlicensed in treating inflammatory bowel disease, it is not reasonable to expect GPs to continue to prescribe the medication after its initiation by the gastroenterology team. The patients were therefore given a 3-monthly prescription on initiation of parenteral treatment and reviewed again in clinic after 3 months. Thereafter, the patients were responsible for contacting us directly in order to request a repeat outpatient prescription every 3 months. This task could be done by an inflammatory bowel disease specialist nurse if available in a unit.

flgastro-2011-100021ds1.pdf (8.8KB, pdf)

Obtaining the agreement and cooperation of pharmacy

It is crucial to have the support of the hospital pharmacy to make this service work. Our pharmacy department was helpful in this service development. It agreed to provide prefilled methotrexate syringes, which patients could then self-administer. The total cost for one prefilled syringe was £5.55 (personal communication with J.Caisley). Prescriptions could be provided for 3 months at a time as they can be stored in a domestic refrigerator.

There were some prerequisites:

-

■

There had to be more than one point of contact in the gastroenterology department so that somebody was always available to answer queries regardless of annual leave and shift work.

-

■

Prescriptions had to be written at least 72 h in advance.

-

■

Prescriptions could not be dispensed unless the patient had been ‘signed off’ as competent to self-administer the parenteral methotrexate (see ‘Cytotoxicity’ and online appendix 2).

-

■

Patients had to collect their own supply of methotrexate from the hospital pharmacy, to avoid delivery costs.

flgastro-2011-100021ds2.pdf (63.5KB, pdf)

Cytotoxicity

Methotrexate is a cytotoxic drug and special handling rules must be observed.7 All patients administering cytotoxic drugs need to know the procedure for handling the drug, be able to manage a spillage and have immediate access to materials required to deal with a cytotoxic spillage. Syringes must be disposed of in a cytotoxic sharps bin, which was provided with the initial prescription and exchanged with collection of the next prescription 3 months later.

Chemotherapy nurses are trained in handling cytotoxic drugs. We work closely with our local chemotherapy day unit and their staff agreed to train our patients for self-administration of SC methotrexate. Once the patients were established on home treatment, capacity within the chemotherapy day unit was increased for other patients.

Funding and cost savings

The annual cost to our primary care trust (PCT) for each patient receiving weekly in-hospital parenteral methotrexate is £6373, based on 52 regular attendances to the hospital day unit, charged at £117 per attendance (2010/2011 tariffs), and the cost of the methotrexate (£5.55 per syringe, non-proprietary preparation, sourced by our hospital pharmacy).

By contrast, the annual cost of self-administered parenteral methotrexate costs the PCT £640. This is achieved by outpatient prescription, with patients collecting their own drugs from pharmacy every 12 weeks, and the need for only 3 day-case attendances for self-administration training.

Self-administered parenteral methotrexate is likely to represent annual savings to the PCT of around £5733 per patient. This saving would be greater if the patient remained on the drug for more than a year, since there would not be a need to repeat training in subsequent years, and the cost to the PCT would be that of the drug alone (£289 for a year's supply of methotrexate). These savings would be of benefit to the National Health Service healthcare economy.

Consent

The most appropriate place for counselling patients about the decision to start methotrexate, and obtaining informed consent was the outpatient department. All eligible patients were given the option of self-administered methotrexate as well as the alternative of attending the hospital weekly. If a patient opted for self-administered methotrexate, a date for injection training was arranged and the usual follow-up organised.

Monitoring

Methotrexate has potentially serious side effects, which patients must be made aware of during the consent process. Treatment requires regular blood test monitoring to detect any potential complications early. The decision to offer the patient self-administered parenteral methotrexate did not alter our standard monitoring protocol (online appendix 3), which is carried out in accordance with national guidelines.8 The initial blood tests were requested by the gastroenterologist prescribing the methotrexate. The same consultant and/or their registrar was responsible for checking all subsequent blood results that were sent from the laboratory to the relevant consultant's secretary. After the dose of methotrexate had been stable for a period of 6 weeks, with normal blood results, the patient's general practitioner (GP) was responsible for arranging further monitoring blood tests. This was agreed with the primary care trust as a shared care plan for inflammatory bowel disease patients on methotrexate or thiopurines. The responsibility for reviewing blood results would be a suitable role for a specialist inflammatory bowel disease nurse.

flgastro-2011-100021ds3.pdf (11.5KB, pdf)

Information for patient and GPs

Information sheets for the patient and their GP (online appendix 4) were given before starting treatment, with information concerning side effects and what to do about them, as well as specific instructions on how to contact the gastroenterology team directly.

flgastro-2011-100021ds4.pdf (12.4KB, pdf)

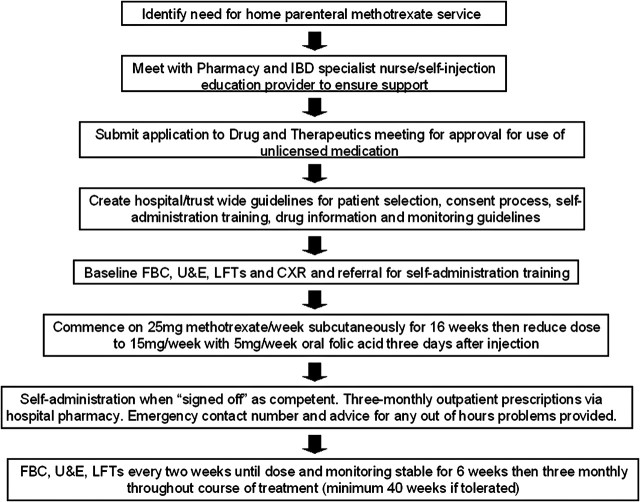

The process for setting up a home parenteral methotrexate service is summarised in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart to summarise factors which need to be addressed in order to establish a safe home methotrexate service. CXR, chest x-ray; FBC, full blood count; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; LFT, liver function test; U & E, urea and electrolytes.

Conclusion

Parenteral methotrexate is of proven benefit in treating patients with Crohn's disease, yet mostly for logistical reasons, gastroenterologists commonly prescribe methotrexate as an oral preparation, despite a lack of evidence supporting its efficacy. The numbers of patients are not huge as this is a second-line treatment for use when patients are steroid dependent or cannot tolerate thiopurines. However, as clinicians, we should be practising evidence-based medicine; therefore we felt it important to deal with this situation, while also improving patient choice and service delivery.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Alfadhli AAF, McDonald JW, Feagan BG. Methotrexate for induction of remission in refractory Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 2004;4:CD003459. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor Al, et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel di0073ease in adults. Gut 2011;60:571–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Irvine EJ, et al. A comparison of methotrexate with placebo for the maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. North American Crohn's Study Group Investigators. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1627–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel V, Macdonald JK, McDonald JW, et al. Methotrexate for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;4:CD006884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nathan DM, Iser JH, Gibson PR. A single center experience of methotrexate in the treatment of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: a case for subcutaneous administration. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;23:954–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.British National Formulary 62 (Sept 2011) section 1.5.3/ www.bnf.org

- 7.Safe Handling of Cytotoxic Drugs. Health and Safety Executive Information Sheet Misc 615. Sept 2003/ www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/misc615.pdf

- 8.Mowatt C, Cole A, Windsor A, et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2011. May;60(5):571–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

flgastro-2011-100021ds1.pdf (8.8KB, pdf)

flgastro-2011-100021ds2.pdf (63.5KB, pdf)

flgastro-2011-100021ds3.pdf (11.5KB, pdf)

flgastro-2011-100021ds4.pdf (12.4KB, pdf)