Abstract

Background

For gastroenterology, The Royal College of Physicians reiterates the common practice of two to three consultant ward rounds per week. The Royal Bolton Hospital NHS Foundation Trust operated a 26-bed gastroenterology ward, covered by two consultants at any one time. A traditional system of two ward rounds per consultant per week operated, but as is commonplace, discharges peaked on ward round days.

Objective

To determine whether daily consultant ward rounds would improve patient care, shorten length of stay and reduce inpatient mortality.

Methods

A new way of working was implemented in December 2009 with a single consultant taking responsibility for all ward inpatients. Freed from all other direct clinical care commitments for their 2 weeks of ward cover, they conducted ward rounds each morning. A multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting followed immediately. The afternoon was allocated to gastroenterology referrals and reviewing patients on the medical admissions unit.

Results

The changes had an immediate and dramatic effect on average length of stay, which was reduced from 11.5 to 8.9 days. The number of patients treated over 12 months increased by 37% from 739 to 1010. Moreover, the number of deaths decreased from 88 to 62, a reduction in percentage mortality from 11.2% to 6%. However, these major quality outcomes involved a reduction in consultant-delivered outpatient and endoscopy activity.

Conclusion

This new method of working has both advantages and disadvantages. However, it has had a major impact on inpatient care and provides a compelling case for consultant gastroenterology expansion in the UK.

Background

Gastrointestinal diagnoses were the primary illness in at least 12% of the 5.2 million emergency medical admissions to UK hospitals during 2009–10.1 This equates to approximately 2500 patients a year in a typical district general hospital serving a population of 250 000. Taking into account the other clinical responsibilities of a gastroenterologist (table 1), The Royal College of Physicians recommends six full-time equivalent consultants, providing 69 programmed activities (PAs) to cover this workload in gastroenterology.2 These calculations included the inpatient workload of between 20 and 25 medical/gastroenterology patients, with three PAs to cover the inpatient workload. In practice, most consultants undertake two ward rounds a week, with the third PA allocated to meeting relatives, completing discharge letters and other ward-related administration. An independent study into the gastroenterology workforce, commissioned by the British Society of Gastroenterology, concluded that the rising burden of gastrointestinal disease already warranted a significant expansion in consultant gastroenterologists.3

Table 1.

Estimated activity required within gastroenterology to serve a population of 250 000. Adapted from the Royal College of Physicians' document, Consultant physicians working with patients2

| Activity | Programmed activity |

|---|---|

| Ward rounds (except on-take and post-take) | 3 |

| Outpatient clinics | 22 |

| Endoscopy | 16 |

| Nutrition service | 2 |

| On-take and mandatory post-take rounds | 1 |

| MDT meetings | 3 |

| Additional direct clinical care | 6 |

| On-call for emergency endoscopy | 1 |

| Total direct patient care | 54 |

| Work to maintain and improve the quality of care | 15 |

| Total | 69 |

MDT, multidisciplinary team.

The Royal Bolton Hospital is part of a Foundation Trust delivering secondary care to a population of 260 000. Four consultant gastroenterologists cover the workload, supported by an associate specialist, a staff grade physician, one registrar, a nurse consultant, two nurse endoscopists and four specialist nurses. The gastroenterology ward is a 26-bed unit. Historically, two consultants were on at any time, each covering 13 patients. Responsibility was also assumed for medical outliers on two surgical wards. As with most doctors, the consultant job plans included two-ward rounds a week.

On review of our working pattern, it was noted that over half of our discharges occurred on ward-round days. A second concern with our service was the way in which gastroenterology specialist input to the medical admissions unit (MAU) was provided. Our team tried to offer consultant or registrar input on the high dependency unit (HDU) and MAU each day to instigate appropriate management or in some cases to facilitate early discharge. Unfortunately, this cover was dependent on individuals finding time in their week to attend the MAU and HDU. There was uncertainty on the HDU/MAU as to when a gastroenterologist might attend and there was inevitable intrusion into scheduled elective work when consultants were asked to review patients ad hoc. In addition, this system did not provide continuity for patients on the MAU, since they were often seen by different members of the team each day.

We had already observed successful outcomes for patients with alcohol-related problems and particularly alcohol-related liver disease by implementing collaborative gastroenterology and psychiatry care.4 5 A weekly multidisciplinary ward meeting was established to discuss these patients' needs. For our broader gastroenterology inpatients, our aim was to combine regular consultant input with closer multidisciplinary team (MDT) working.

Daily consultant ward rounds and MDT meetings

In September 2009, an alternative model was designed and subsequently implemented in December 2009, with the introduction of daily consultant ward rounds, followed by an MDT meeting. One consultant now takes sole responsibility for the gastroenterology ward. Clinical ward rounds take place Monday to Friday between 09:15 and 11:45. At 11:45, there is an MDT meeting for the ward, lasting 30–40 min, involving the nursing staff, alcohol specialist nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, social workers and dieticians. It is patient-centred, each problem being prioritised and discussed, with input from all relevant healthcare professionals. A predicted date of discharge is reviewed daily, so that individual members of the team complete their responsibilities in parallel rather than in series.

While covering the wards, the consultant is now free from all other PAs. Hence, in the afternoon, they can visit the MAU/HDU, see referrals from other specialties, cover emergencies in endoscopy, meet relatives on the ward and review the progress of gastroenterology ward patients. With one consultant accepting the inpatient workload for 2 weeks at a time, the other three consultants are free to focus on outpatient clinics, endoscopy and all other supporting activity, without interruption from the acute inpatient workload.

Challenges of change

In practice, the focused daily ward round has suited some consultants more than others, with a calculated average time of less than 6 min per patient. It has proved particularly challenging to fully appreciate the clinical and social problems of all 26 patients on the first day of a 2-week period of ward cover. Delaying the MDT is never considered, since there is the option of completing the ward round in the afternoon, which almost always is the case on the first Monday of consultant ward cover. Starting the MDT on time is felt to be critically important, since this supports attendance and encourages an efficient and rapid MDT. In practice, either the physiotherapist or occupational therapist attends, since they work closely together. Finally, owing to responsibilities on other wards, our social worker can only attend the meeting 3 days a week. On other days, she is contacted immediately after the meeting with any specific concerns or requests. A semiformal handover has been introduced at the end of a 2-week period, when the incoming consultant attends the Friday MDT to hear about the patients and discuss problems.

Impact on the care of gastroenterology ward patients

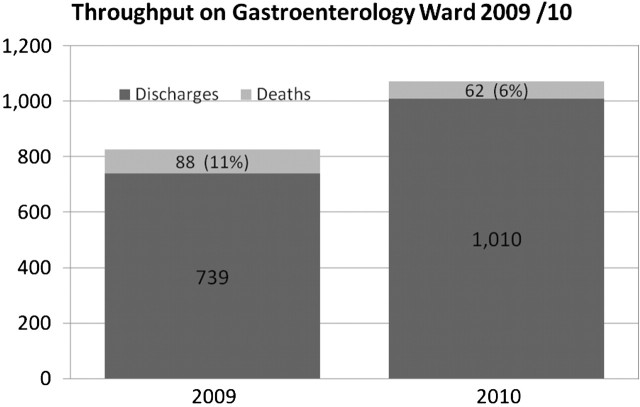

A comparison of the first 12 months of the new method of working with the preceding 12-month period, showed a marked reduction in length of stay. Average length of stay was reduced by almost a quarter, from 11.5 days in 2009 to 8.9 days in 2010. This equated to a throughput of 1072 patients, compared with 827 patients with the traditional system of two-ward rounds per consultant per week (figure 1). Even more impressive was the percentage, as well as the absolute, reduction in inpatient mortality. Eighty-eight patients died in 2009, which was 11% of total admissions. This figure is comparable to the preceding years, when the mortality was 12.6% for 2007 and 11.3% for 2008. In 2010, with daily consultant ward rounds and MDTs, inpatient deaths were reduced to 62 patients, or just 6% of total admissions. The 30-day mortality reduced from 121 (15%) to 87 (8%).

Figure 1.

Number of patients treated in the gastroenterology ward of Royal Bolton Hospital in 2009, while operating a traditional model of two-ward rounds per consultant per week, and in 2010, when daily consultant ward rounds were introduced. The number and percentage of deaths before and after the change are also shown.

Although the 30-day mortality reflects appropriateness of discharges, further indirect data are available. First, the proportion of patients transferring to another ward was reduced from 20% to 8.5%. The majority of transfers were patients who were placed in other wards because they were sufficiently medically fit, but were not well enough to go home. Coupled with the reduced length of stay, the increased discharge of patients suggests that we were more efficient at completing investigations and treatment. Patients were not simply admitted and rapidly transferred to an alternative secondary care area. In addition, despite the rapid turnover, the 30-day readmission rates in 2009 and 2010 were identical at 12%.

Other benefits are much harder to quantify, but included improved communication with patients, families and staff through continuity of care. Families were more easily able to meet consultants, who were now available daily. Decisions about end-of-life care and resuscitation occurred earlier and at a more senior level.

Characteristics of admitted patients varied very little, with a mean age of 57 in 2009 and 55 years in 2010. The primary diagnosis was gastroenterological in 90% and 92% of cases, respectively.

Impact on patient care on other wards

The MAU benefited from a reliable, daily gastroenterology input, which had previously been sporadic. Before daily consultant ward rounds, a monthly rota was drawn up. Requests were emailed to the gastroenterology team, asking for volunteer days when they might find time to visit the MAU. With this system, there was no commitment as to when the gastroenterologist would attend, which meant that the MAU still relied on the written referral system. With the new method of working, MAU patients were highlighted for gastroenterology review on the established patient tracking software, and no written or verbal referral was required. Emergency cases could still be discussed, since the MAU team was aware that telephoning the gastroenterology ward in the morning allowed an initial discussion with the gastroenterologist, followed by an early clinical review, if indicated. Similarly, referrals from other specialties were treated promptly, with an opinion given on the same day in most cases. Although it is difficult to quantify this improvement, the increased accessibility, coupled with the reliable and prompt gastroenterology input throughout the hospital, was appreciated by nursing, medical and management colleagues.

Impact on consultant PA

Six PAs a week were required to service the traditional model, but ward referrals, endoscopy emergencies and MAU input were never factored into this activity. With daily consultant ward rounds, five PAs were required for the ward rounds and an additional five PAs were allocated as direct patient care, in order to cover the remaining clinical workload. We estimated a loss of five outpatient clinic/endoscopy sessions each week, although there might have been an increase in outpatient and endoscopy activity among the three consultants not covering the wards. The precise impact on endoscopy and clinic activity was hard to quantify, owing to a number of confounding factors. In 2010, we employed an extra staff grade physician, who assisted in the clinic and with endoscopy activities. There has been an increasing commitment to bowel cancer screening and consultant job plans have changed, so that any free time created was not necessarily reallocated to clinics or endoscopy. There was a 36% reduction in consultant-delivered endoscopic procedures (gastroscopy and colonoscopy), but a <10% reduction in the number of clinics held. We estimated the cost to the Trust to be four PAs.

Discussion

Daily consultant ward rounds and daily MDT meetings have dramatically improved the average length of stay and inpatient mortality for our gastroenterology ward. It is not possible to separate the impact of daily ward rounds from daily MDTs and we perceive both as key, complementary interventions. From a static mortality of around 11%, we have seen an immediate impact, which has been maintained at 1 year. This reduction in mortality is undoubtedly the most important and impressive finding. Daily consultant ward rounds have influenced the outcomes for our sickest patients, as well as for those with more minor illnesses.

A shorter length of stay alone might be partly due to the consultant being more comfortable in discharging patients than junior doctors, who tend to keep patients in hospital until a consultant ward round. However, the key factor is that daily multidisciplinary care ensures that each of the patient's problems and the concerns of their families are dealt with. In particular, the input from a dedicated social worker greatly influences length of stay and facilitates discharge to a suitable environment.

The reduced average length of stay is of interest, especially given the strain on NHS budgets. Ward expenditure, which is dominated by nursing staff salaries, was broadly similar across the 2 years. However, under ‘payment by results’, we would expect a sizeable increase in revenue.

Potential confounding factors included a change in consultant level appointments, with SS being appointed in September 2010. However, this is unlikely to have influenced outcomes, since he served only 3 weeks as ward consultant during the entire study period. In addition, the preliminary data, comparing the first half of 2009 with the first half of 2010 (when there were no changes in consultant personnel), showed equally positive results. Junior doctors during this period have changed, with 4-monthly rotations, but each team of juniors has been of similar high quality. To exclude the possibility that 2009 happened to be a particularly bad year, mortality figures for 2007 and 2008 were also extracted. They were similar to the 2009 data, providing further support for a true reduction in mortality.

The daily consultant visits to the MAU certainly influenced the timely implementation of optimal care and which patients were transferred to the gastroenterology ward. However, most routine decisions to transfer still lay with the bed managers. Hence, it is unlikely that this had an important influence. With just one gastroenterology ward, the overall strategy had not changed and gastroenterology patients were still identified by the MAU team in the same way. Finally, neither the primary diagnosis nor the median age changed sufficiently to account for the improvements reported.

Another potential confounder might be more rapid access to diagnostic tests, but we could not identify any changes in laboratory medicine, radiology or endoscopy services. Finally, no other change throughout the Trust, new equipment or new practice was identified that might have been a potential confounder.

It is evident that early gastroenterology review and the instigation of timely, appropriate management of patients who are severely ill with gastrointestinal and liver disease influenced their length of stay and mortality. Indeed, it is critical that specialists see appropriate patients at an early stage and this was always part of the overall strategy of daily consultant ward rounds. Interestingly, despite the natural assumption that specialist input improves outcomes, there is a paucity of evidence in the gastroenterology field.6 With gastrointestinal bleeding, one retrospective study demonstrated that specialist input may reduce length of stay,7 but there are few quality studies showing a clear benefit from specialist input. Our study is perhaps one of the strongest pieces of evidence that specialist consultant care influences outcomes.

Whether our system could be successfully applied across all specialties and in all hospitals is unclear. The value of daily consultant ward rounds in older care, for example, seems more doubtful, since older people often require a longer period of convalescence from any given illness. In this case daily decisions may not always be so important.

Diagnostic departments need to be set up to offer services to inpatients with minimal delay, as there seems little point in a daily review if investigations or clinical findings have not progressed. The Royal Bolton Hospital has a dedicated team, trained in assisting specialties to develop quality improvements, with the key philosophy of incorporating ‘lean’ methodology and reducing waste. As part of this strategy, there are stringent efforts to avoid delay, which is seen as waste.

In addition to assessing diagnostic support, hospitals should review their gastroenterology workforce. Departments with fewer than four consultants might hesitate to implement this change in working practice, since the impact on outpatients and endoscopy activities will be proportionately greater. Conversely, the shift to daily consultant ward rounds, with the loss of clinics and endoscopy sessions, as we have found, should form the cornerstone of a business plan to expand the consultant gastroenterologist workforce throughout the UK.

During the planning phases, education and training of junior doctors was considered in view of the possibility of diminished responsibility affecting competence. However, questionnaires to the juniors showed a very high level of satisfaction with the changes. In addition, registrars were allowed to conduct ward rounds under direct consultant observation, which was felt to be a particularly beneficial and rare training opportunity. It remains to be determined how daily consultant ward rounds will affect different levels of trainee, but our feeling is that it is likely to have an overall positive effect on accurate decision-making.

Some of the benefits and disadvantages of the new daily consultant ward rounds are listed in table 2. The clinical impact of these changes, as well as our unit's enthusiasm for the new system, has been so overwhelmingly positive that gastroenterology at The Royal Bolton Hospital is unlikely to revert to the previous format of two ward rounds a week. At Royal Bolton Hospital, our new way of working is likely to expand into other specialties, and respiratory medicine already operates a similar model. Further work will examine whether these benefits are sustained beyond the initial period, when enthusiasm is greatest, or indeed, whether further refinements might deliver even greater benefits for patients.

Table 2.

Benefits and disadvantages of daily consultant ward rounds

| Benefits | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Improved quality of care for example: | Loss of outpatient clinic and endoscopy sessions |

| Early intervention for deteriorating patients | |

| Better assessments | |

| More timely reviews of drugs | |

| Lower mortality for inpatients | Requires rapid review |

| Reduced length of stay for inpatients | Requires prompt investigations from diagnostic departments |

| Juniors are not required to make unsupported decisions | Juniors tend to leave routine decisions to consultants |

| More predictability for juniors to prepare for ward round | Less time for questions from juniors on each ward round |

| Juniors are taught every day | |

| Greater guidance for the multidisciplinary team | |

| Improved team working | |

| Encourages parallel, nurse-led, quality initiatives | |

| Consultant access for patients and families | |

| Fewer interruptions to consultants' daily work when not on the wards |

In the past, consultants often delegated ward rounds to their senior registrars. In the modern NHS, with greater accountability, most consultants see their inpatients twice a week. This has been perceived as a ‘consultant-led’ service; a term that has became a political badge in the NHS over the past 10 years. Our new way of working provides a compelling case for ‘consultant-delivered’ care. Clearly, if ‘consultant-delivered’ endoscopy and outpatient services are to be maintained, and indeed developed to enhance patient choice, quality standards and outcomes, consultant gastroenterology expansion in the UK is required.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the nursing staff, junior doctors, allied health professionals and social workers who were always flexible and regularly contributed to the evaluation and redesign of patient care and services.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributors: SS analysed the data and wrote the paper. GL designed the changes in service delivery and contributed to the writing of the paper. KP and RR implemented the changes in service delivery and contributed to the writing of the paper. SR designed the changes in service delivery and collected the data. VB designed the changes in service delivery. SC and ED were involved in the implementation of change in service. KM implemented the changes in service and co-wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Department of Health. Hospital Episode Statistics. London: Department of Health, 2010. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Statistics/HospitalEpisodeStatistics/index.htm (accessed 1 June 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Royal College of Physicians. Consultant physicians working with patients. Fourth edition London: RCP; 2008. 140–152. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams JG, Roberts SE, Ali MF, et al. Gastroenterology services in the UK. The burden of disease, and the organisation and delivery of services for gastrointestinal and liver disorders: a review of the evidence. Gut 2007;56(Suppl 1):1–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moriarty KJ, Platt H, Crompton S, et al. Collaborative care for alcohol-related liver disease. Clin Med 2007;7:125–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moriarty KJ. Collaborative liver and psychiatry care in the Royal Bolton Hospital for people with alcohol-related disease. Frontline Gastroenterology 2011;2:77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Provenzale D, Ofman J, Gralnek I, et al. Gastroenterologist specialist care and care provided by generalists–an evaluation of effectiveness and efficiency. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:21–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quirk DM, Barry MJ, Aserkoff B, et al. Physician specialty and variations in the cost of treating patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology 1997;113:1443–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]