Abstract

Background

Voluntary Leapfrog Safe Practices Scores (SPS) were among the first public reports of hospital performance. Recently, Medicare's Hospital Compare website has reported compulsory measures. Leapfrog's Hospital Safety Score grades incorporate SPS and Medicare measures. We evaluate associations between Leapfrog SPS and Medicare measures, and the impact of SPS on Hospital Safety Score grades.

Methods

Using 2013 hospital data, we linked Leapfrog Hospital Safety Score data with central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) and catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) Standardized Infection Ratios (SIRs), and Hospital Readmission and Hospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) Reduction Program penalties incorporating 2013 performance. For SPS-providing hospitals, we used linear and logistic regression models to predict CLABSI/CAUTI SIRs and penalties as function of SPS. For hospitals not reporting SPS, we simulated change in Hospital Safety Score grades after imputing a range of SPS.

Results

1,089 hospitals reported SPS; >50% self-reported perfect scores for all but one measure. No SPS were associated with SIRs. One SPS (feedback) was associated with lower odds of HAC penalization (OR=0.86, 95% confidence interval=0.76, 0.97). Amongst hospitals not reporting SPS (N=1,080), 98% and 54% saw grades decline by 1+ letters with 1st and 10th percentile SPS imputed, respectively; 49% and 54% saw grades improve by 1+ letter with median and highest SPS imputed.

Conclusions

Voluntary Leapfrog SPS skew towards positive self-report with little association with compulsory Medicare outcomes and penalties. SPS significantly impact Hospital Safety Score grades, particularly when lower SPS is reported. With increasing compulsory reporting, Leapfrog SPS appear limited for comparing hospital performance.

Keywords: Health policy, safety, hospital-acquired conditions, readmission

Introduction

Available metrics for comparing hospital safety have expanded in recent years. These measures have transitioned from voluntary self-report to compulsory national collection of standardized instruments, such as those on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Hospital Compare website.1

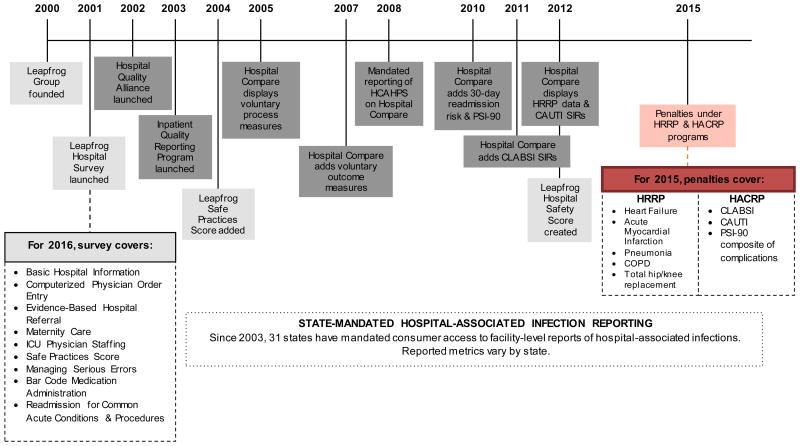

Figure 1 illustrates the timeline of hospital and patient safety measure development. The Leapfrog Group, founded in 2000 by employers to encourage transparency of hospital performance, provided the earliest measures.2 In 2001, they launched the Leapfrog Hospital Survey, a voluntary instrument covering hospital and patient safety process and outcome measures. In 2004, Leapfrog added self-reported Safe Practices Scores (SPS) measures3 built from 34 National Quality Forum-endorsed practices to reduce risk of patient harm in acute care hospitals.4 Leapfrog SPS measures focus on implementing structures or protocols reflective of accountability, rather than objective outcomes. SPS initially included 27 measures, and trimmed to 8 in 2013 (Supplemental Table 1). In 2012, the SPS was bundled with other process and outcome measures to inform a more consumer-friendly composite Hospital Safety Score (HSS) rating hospitals on a scale ranging from 0 to 4, and providing a single corresponding letter grade of “A” (Best), “B”, “C”, “D” or “F” (Worst) (Supplemental Table 2).5 Hospital self-reports on the eight SPS measures are available for consumers to compare across hospitals on the HSS website;6 they also account for a substantial portion of the HSS (22.6% of total score; 45% of ‘Process and Structural Measures’ domain).

Figure 1.

Timeline for collection of voluntary and compulsory patient safety metrics and content overview.

CLABSI: Central line-associated bloodstream infections; CAUTI: Catheter-associated urinary tract infections; HCAHPS: Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems; HRRP: Hospital Readmission Reduction Program; HACRP: Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program; PSI-90: Patient Safety Indicators #90; SIR: Standardized infection ratio

Over time, compulsory measures of hospital quality and patient safety were developed. In 2002, the Hospital Quality Alliance, a public-private partnership, formed to support hospital quality improvement and improve consumer healthcare decision-making.7 Their efforts created the Hospital Compare website,1 a consumer-facing website focused on improving consumer decision-making by providing hospital performance and safety metrics. Hospital Compare first mandated reporting in 2008, requiring hospitals to report patient satisfaction and mortality measures or face a 2% reduction in CMS annual payment update.8 Hospital Compare measures now include hospital-associated infections and complications, including central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI), catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Patient Safety Indicators (PSI).

In 2012, Hospital Compare began reporting data from two new CMS value-based purchasing programs. The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) aims to decrease unplanned 30-day readmissions following select procedures for certain conditions.9 The Hospital-Acquired Conditions Reduction Program (HACRP) targets reduction in incidence of hospital-acquired conditions (HACs) including CLABSI, CAUTI and serious complications of treatment.10 In 2015, hospitals whose HACs or readmissions during the evaluation period exceeded expected values could be penalized up to 1% (under HACRP) or 3% (under HRRP) of total hospital Medicare reimbursement.

It is unclear how well Leapfrog's voluntary SPS correlate with more recent compulsory Medicare metrics displayed by Hospital Compare. Prior work demonstrated Leapfrog's voluntary nature over-represents ‘high quality’ hospitals,11 and tied Leapfrog-led implementation efforts with improved process quality and decreased mortality rates12 and surgical death;13 however SPS measures have shown no relationship with all-cause or surgical mortality14, 15 or trauma outcomes, including hospital-associated infections.16 Given these mixed findings, this paper addresses two objectives: first, amongst hospitals reporting SPS, evaluate how well Leapfrog's SPS correlate with compulsory outcomes and penalties for readmission and complications publicly-reported on Medicare's Hospital Compare; and second, amongst hospitals not reporting SPS, evaluate the potential impact of SPS on Leapfrog's HSS grades using imputed SPS to simulate new HSS.

Methods

Data sources

For all analyses, we combined data from four sources: (1) the Spring 2014 Leapfrog HSS dataset, which includes hospital grades, SPS measures as reported in the 2013 Leapfrog Hospital Survey, and all other HSS components listed in Supplemental Table 2; (2) Hospital Compare data on CLABSI and CAUTI in 2013; 17 (3) Hospital Compare data on penalties assessed under the HRRP and HACRP in 2015; 17 and (4) hospital characteristics from the 2013 American Hospital Association (AHA) Survey Database.

Objective 1: Do Leapfrog SPS measures predict publicly-reported outcomes and penalties?

Predictor variables

Our predictor variables were Leapfrog SPS measures (Supplemental Table 1) for hospitals that reported SPS measures. We selected five individual SPS measures as representative of direct pathways from standards of care to study outcomes, as well as Total SPS. AHA data was used to control for hospital characteristics: bed size (< 50, 50-200, and > 200 beds); ownership (public, private non-profit, private for-profit); Council of Teaching Hospitals membership; and safety net status, defined as ≥1 standard deviation more Medicaid patients than state average.

Dependent variables

We examined 4 publicly-reported outcome variables: CLABSI and CAUTI Standardized Infection Ratios (SIRs), and penalization under HRRP or HACRP.

CLABSI and CAUTI SIRs

Hospital Compare CLABSI and CAUTI SIRs were reported to the National Health and Safety Network (NHSN) from April 1, 2012-March 31, 2013. SIRs are risk-adjusted measures dividing the number of observed infections by the number of predicted infections calculated from CLABSI or CAUTI rates from a standard population throughout a baseline time period.18-20 SIRs greater than 1.0 indicate more infections observed than predicted, while SIRs less than 1.0 indicate fewer observed than predicted.21

Penalties

2015 HRRP penalties covered readmissions from July 1, 2010-June 30, 2013. Readmissions penalties are calculated via the Readmissions Adjustment Factor (RAF), which incorporates a risk-adjusted excess readmission ratio and diagnosis-related group payments for all included conditions.22 2015 HAC penalties used CLABSI and CAUTI rates from January 1, 2012-December 31, 2013, and PSI-90 from July 1, 2011-June 30, 2013. HAC penalties were computed from the average decile of performance for the NHSN CAUTI and CLABSI rates, weighted at 65%, plus the decile of performance for the PSI-90, weighted at 35%.10 For both programs we examined a binary measure of penalization.

Analysis strategy

To examine the relationship between Leapfrog SPS measures (individual and total) and CLABSI and CAUTI SIRs, we looked at bivariate correlations and used linear regression to evaluate the effect of SPS on outcomes, controlling for hospital characteristics. For penalties, we computed point-biserial correlations between SPS measures and penalty indicators, and then used binary logistic regression to evaluate effect of SPS on odds of penalization, controlling for hospital characteristics. All analyses were performed using Stata MP Version 14.123 and a 0.05 two-sided significance level.

Objective 2: How much can voluntary SPS measures impact HSS grades?

Predictor variables

Imputed SPS measures were our main predictors of interest. Because we were interested in their impact on HSS grades for hospitals that did not report them, four sets of SPS measures were imputed for hospitals, based on the distribution of SPS measures for hospital that did report: lowest SPS measures (1st percentile); low (10th percentile); median (50th percentile); and highest (100th percentile). As control inputs, we also included hospital data as observed for all other HSS components listed in Supplemental Table 1, as provided in the HSS database.

Dependent variable

Our dependent variable was overall HSS, which ranges from 0-4; and corresponding HSS grades, which range from “A”-“F”.

Analysis strategy

We simulated change in HSS and grades after imputing SPS measures using the methodology reported by Leapfrog for their Spring 2014 HSS.24 HSS comprise weighted Z-scores (trimmed at 99th percentile, or Z=±5) across two domains: Process and Structural Measures (50% of total HSS); and Outcomes (remaining 50%). SPS measures account for 8 of 15 Process measures, or 22.6% of the total score. Hospitals that do not report SPS have other Process measures upweighted proportionally by Leapfrog. To simulate new scores imputing missing SPS measures at lowest, low, median, and highest levels, we converted the 8 SPS measures into Z-scores, trimmed as appropriate, and recalculated weights for Process measure scores including SPS measures, before recalculating the Process domain score and subsequent total HSS. No changes were made to Outcome domain scores. Simulated scores for different values of SPS were then compared to original scores to evaluate change in score and letter grade.

Study population

Supplemental Figure 1 illustrates the study flow diagram. 2,530 hospitals were included in the Spring 2014 HSS database. 2,178 had AHA data; either CLABSI or CAUTI SIR; and either HRRP or HACRP penalty data. 1,098 hospitals (50.4%) provided SPS and were included in our Objective 1 analyses; 1,080 (49.6%) declined to report SPS and were used for Objective 2 analyses.

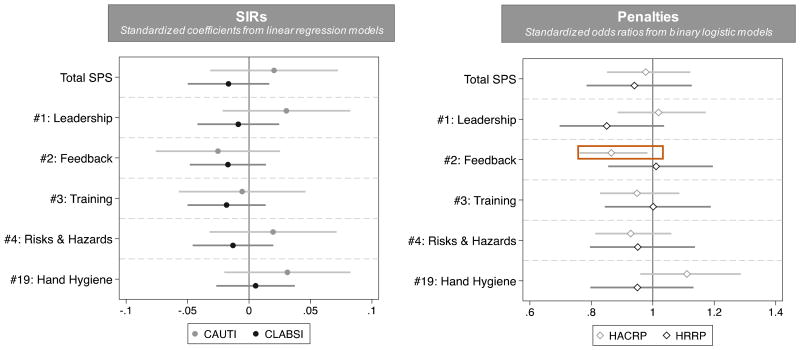

Figure 2.

Is there an association between Leapfrog Safe Practices Score (SPS) and rates of CLABSI and CAUTI reported by Hospital Compare, or penalization for excessive readmission or hospital-acquired conditions? Coefficients and 95% confidence intervals from multivariate regression models, by individual and total SPS

SIR = Standardized Infection Ratio; CAUTI = Catheter-associated urinary tract infection; CLABSI = Central line-associated bloodstream infection; HACRP = Hospital-acquired Complication Reduction Program; HRRP = Hospital Readmission Reduction Program. Standardized coefficients presented for all SPS measures, indicating the change in dependent variable for a standard-deviation change in SPS measure. SIR models estimated as linear regression models. Penalty models estimated as binary logistic models, with odds ratios presented here. All models include controls for hospital size, ownership, teaching status, and safety net status.

The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt from oversight.

Results

Summary statistics

Distributional statistics for SPS measures (Table 1) show highly skewed distributions for all individual measures. For all but one measure (SPS #1), the median score is also the highest score, indicating that at least 50% of hospitals self-report perfect data. 1st percentile values generally correspond to receipt of 1/3 of possible points for an individual measure; and 10th percentile values to 3/4 of possible points. Mean total SPS was 444.40; 213 hospitals (19.4%) reported a perfect 485.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and distributions for Leapfrog Safe Practices Score measures.

| Safe Practices Score (SPS) Measures | Distribution (Scores used for imputation in Objective 2) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Potential Range |

|

|

| #1: Culture of Safety Leadership Structures & Systems | 111.28 (12.72) |

0-120 |

|

| #2: Culture Measurement, Feedback & Intervention | 18.09 (4.56) |

0-20 |

|

| #3: Teamwork Training & Skill Building | 34.97 (8.55) |

0-40 |

|

| #4: Risks & Hazards | 110.30 (17.31) |

0-120 |

|

| #9: Nursing Workforce | 92.31 (14.02) |

0-100 |

|

| #17: Medication Reconciliation | 31.93 (5.34) |

0-35 |

|

| #19: Hand Hygiene | 27.65 (4.54) |

0-30 |

|

| #23: Healthcare-Associated Complications in Ventilated Patients | 18.42 (2.88) |

0-20 |

|

| Total SPS | 444.40 (54.47) |

0-485 | Total score not used in imputations |

Note: Measures in red are examined as predictors or publicly-reported outcomes and penalties under Objective 1; all SPS measures except Total are used for simulating new Hospital Safety Scores under Objective 2. Underlined terms correspond to SPS measure descriptors displayed in Figure 2.

With respect to hospital characteristics, outcomes and grades (Table 2), the 2,178 hospitals included 279 (12.8%) teaching hospitals and 305 (14.0%) safety-net hospitals. Ownership was predominantly private, not-for-profit (70.3%); the majority had > 200 beds (60.7%). Average CLABSI SIR across all hospitals was 0.55, similar to the national baseline of 0.54, and average CAUTI SIR was 1.03 compared to the national baseline of 1.07.25 Of note, NHSN SIRs analyzed here had baselines from 2008, with declines reflecting both improvements in care and NHSN definition changes. NHSN will use 2015 data to re-baseline SIRs in January 2017.26 1,875 hospitals (86.1%) received a penalty under HRRP in 2015, and 582 (26.7%) were penalized for HAC. Compared to hospitals declining SPS, those providing SPS were larger (p<0.001) and more for-profit (p=0.001). CAUTI and CLABSI SIRs and penalization rates did not vary significantly by SPS provision. However, hospitals that provided SPS scores were graded significantly higher than hospitals that declined; 510 (46.5%) hospitals providing SPS received an “A” grade, compared to 193 (17.9%) hospitals declining SPS (p<0.001).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for hospital characteristics, Hospital Compare CLABSI & CAUTI SIRs, penalization, and Hospital Safety Score grades for Spring 2014, overall and by provision of Leapfrog Safe Practices Scores.

| Overall (N=2,178) |

Provided Safe Practices Score (N=1,098) N (%) or Mean (SD) |

Declined Safe Practices Score (N=1,080) N (%) or Mean (SD) |

Test statistics & p-value for difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Hospital Association Hospital Characteristics | ||||

|

Teaching hospital? (1=Yes) |

279 (12.8) | 150 (13.7) | 129 (11.9) | X2(1)=1.43 p=0.23 |

| Bed size | X2(2)=21.09 p<0.001 |

|||

| <50 | 18 (0.8) | 9 (0.8) | 9 (0.9) | |

| 50-200 | 837 (38.4) | 370 (33.7) | 467 (43.2) | |

| >200 | 1363 (60.7) | 719 (65.5) | 604 (55.9) | |

| Ownership | X2(2)=34.31 p=0.001 |

|||

| Public | 249 (11.4) | 94 (8.6) | 155 (14.3) | |

| Private, not for profit | 1,531 (70.3) | 761 (69.3) | 770 (71.3) | |

| Private, for profit | 398 (18.3) | 243 (22.1) | 155 (14.4) | |

|

Safety net hospital? (1=Yes) |

305 (14.0) | 146 (13.3) | 159 (14.7) | X2(1)=0.92 p=0.34 |

| OUTCOME VARIABLES | ||||

| Hospital Compare Standardized Infection Ratios (SIR) | ||||

| Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections (CLABSI) | 0.55 (0.51) | 0.55 (0.50) | 0.56 (0.52) | t=-0.23 p=0.82 |

| Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections (CAUTI) | 1.03 (0.88) | 1.05 (0.87) | 1.01 (0.89) | t=1.08 p=0.28 |

| Penalized in 2015 under… | ||||

| Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) | 1,875 (86.1) | 942 (85.8) | 933 (86.4) | X2(1)=0.16 p=0.69 |

| Hospital Acquired Conditions Reduction Program (HACRP) | 582 (26.7) | 306 (28.0) | 276 (25.7) | X2(1)=1.45 p=0.23 |

| HOSPITAL SAFETY SCORE GRADES ASSIGNED IN SPRING 2014 | ||||

| A | 703 (32.3) | 510 (46.5) | 193 (17.9) | z=15.79 p<0.001 |

| B | 588 (27.0) | 299 (27.2) | 289 (26.8) | |

| C | 748 (34.3) | 251 (22.9) | 497 (46.0) | |

| D | 119 (5.5) | 35 (3.2) | 84 (7.8) | |

| F | 20 (0.9) | 3 (0.3) | 17 (1.6) | |

Note: Test statistics include X2 (with degrees of freedom) for nominal variables, t-tests for continuous variables, and nonparametric trend tests (z-distribution) for ordinal variables.

Objective 1: Do Leapfrog SPS measures predict publicly-reported outcomes and penalties?

Bivariate correlations between SPS measures and outcomes were consistently weak (range -0.05 to 0.05, Supplemental Table 3).

CLABSI and CAUTI SIRs

Figure 2, left panel presents standardized regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals from linear regression models predicting CAUTI and CLABSI SIRs, controlling for hospital characteristics (full model results in Supplemental Table 4). Neither individual nor Total SPS were significant predictors of CLABSI or CAUTI SIRs.

As sensitivity analyses, negative binomial models of observed infections were also estimated with an exposure for number of catheter days. These models also revealed no associations. We also compared the CAUTI/CLABSI SIRS self-reported in Leapfrog Hospital Survey with these same hospitals' CAUTI/CLABSI SIRs reported on Medicare's Hospital Compare. Note that Leapfrog uses CLABSI and CAUTI SIRs reported in the Leapfrog Hospital Survey as the primary data source for the HSS, and Hospital Compare SIRs as a secondary data source. This analysis revealed similar CLABSI SIRs, but significantly lower CAUTI SIRs, even after accounting for Leapfrog's trimming of extreme values, with a mean CAUTI rate 0.47 reported in the Leapfrog Hospital Survey, compared to 1.05 in Hospital Compare (Supplemental Figure 2).

Penalties

Figure 2, right panel presents odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from binary logit models predicting penalization under HRRP or HACRP, controlling for hospital characteristics (full model results in Supplemental Table 5). No SPS were significantly associated with penalization under HRRP, net hospital characteristics. One SPS (Culture of Measurement, Feedback and Intervention) was significantly associated with penalization under HACRP, with a standard deviation increase in measure score decreasing odds of penalization by a factor of 0.87 (CI: 0.76, 0.97). On average, this equates to a 2.7 percentage point decrease in probability of penalization. Sensitivity analyses used censored linear regression models to examine associations between SPS and HRRP RAF (range: 0.97-1.00) and HACRP Total HAC Score (range: 1-10). Correlations remained very small (range: -0.01-0.06) and only one SPS measure showed a significant association in either model (Supplemental Table 6).

Objective 2: How much can voluntary SPS measures impact Leapfrog's HSS grades?

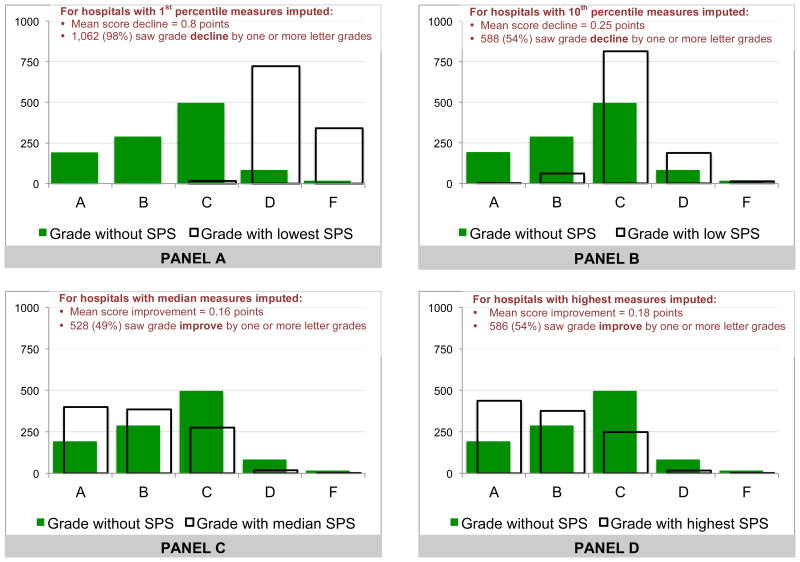

With lowest SPS (1st percentile; Figure 3, Panel A) imputed, hospitals saw grades decline by 0.8 points (out of 4), on average. 1,062 (98%) of hospitals' grades declined by one or more letter grades and very few hospitals (N=16; 1.5%) received a grade higher than D. Imputing 10th percentile grades for SPS (Figure 3, Panel B) resulted in a 0.25-point decline in score, with 588 (54%) of hospitals' grades declining by one or more letter grade. Alternatively, 9 hospitals' (8%) grades improved by one letter grade.

Figure 3.

How much impact do voluntary SPS have on Leapfrog Hospital Safety Score Grades? Change in grades after imputing 1st percentile, 10th percentile, median and highest SPS scores

Imputing median SPS (Figure 3, Panel C) resulted in a small improvement of 0.16 points, on average, in HSS, which improved grades for 528 hospitals (49%) by one or more letter. Imputing highest SPS (Figure 3, Panel D) resulted in only marginally more improvement, improving scores by 0.18 points, on average, and improving grades by one or more letter grades for 586 hospitals (54%).

Discussion

The Leapfrog Group has been a vanguard in developing and publicizing novel measures to inform patient choice. As the market of measures has grown more crowded, their niche is increasingly delineated by two proprietary measures: eight NQF-inspired SPS measures; and the HSS and grade, with Leapfrog SPS as its sole proprietary component. This study reports two major findings. First, there is a lack of meaningful association between voluntary SPS measures and compulsory-reported patient outcomes and Medicare penalties for complications and readmissions. Second, the highly positively-skewed voluntary SPS measures strongly impact the Leapfrog HSS beyond compulsory scores, so that imperfect SPS scores often result in lower grades.

Several mechanisms could underlie the lack of association between SPS and outcomes and penalties, yet lack of variation within these measures (Table 1) is responsible for much of the limited predictive ability. The observed lack of variation, meanwhile, could be due to selection effects; hospitals able to reliably report high scores may be more likely to volunteer. Alternatively, and given that hospitals have a clear incentive to score themselves highly, participating hospitals may inflate their SPS reports, resulting in the skewed distributions and undermining the measures' predictive value. As Leapfrog's SPS' focus on processes and protocols linked to accountability (e.g., protocols for handwashing for SP #19) rather than hard outcomes (e.g., handwashing compliance), hospitals also have a strong incentive to produce minimal protocols that signal compliance but may do little to impact clinical practice.

Even with accurate data, however, SPS measures may not reflect the outcomes highlighted in this study. Although prior work has argued that SPS measures are more likely to be associated with complications than mortality,14 hospital variation in validity of CLABSI and CAUTI reports potentially correlates meaningfully with SPS measures. For example, hospitals with better reporting might also have higher SPS, which could cancel out more conventional negative associations.

Our analyses also show that Leapfrog SPS measures, when provided, can substantially impact a hospital's HSS and grade—however, again due to the highly skewed distributions of the SPS measures, on average, there is more potential for low scores to negatively impact a hospital's grade than for high scores to improve a grade. Indeed, as most hospitals report perfect scores for most SPS measures, hospitals accurately reporting scores that fall in the lower half of the potential distribution end up with z-scores for these measures that are strongly negative (up to the trim point of -5). Given the composite weight of these measures—nearly ¼ of the total HSS—low (or even lower than perfect) SPS can take a hospital's grade from “A” to “B”, or even “C”. For hospitals that are uncomfortable with or unable to report very high SPS, the current Leapfrog methodology thus presents a strong incentive against reporting SPS.

Alternatively, hospitals that improve SPS and/or report high, or even perfect, scores gain relatively modest advantages in their HSS. Perversely, there were 24 hospitals whose HSS declined after the highest SPS were imputed. This result is a function of the Leapfrog methodology converting highly skewed distributions into z-scores—in these cases, the most positive z-scores allowable by the SPS distribution were lower than the positive z-scores they had received for other Process measures; including SPS resulted in downweighting of these larger z-scores, and thus a lower grade. Leapfrog's methodology, in tandem with the highly skewed SPS, results in a system that punishes hospitals whose scores fall at the lower end of the distribution far more significantly than it rewards those hospitals falling at the highest end.

Our study has several important limitations. First, we assess associations only amongst hospitals with all metrics of interest available; broader inclusion may have revealed more associations between SPS and outcomes. Second, we assess relationships between SPS and outcomes at one time point, thus ignoring potential for association over time, or correspondence between change in SPS and change in patient safety outcomes. Third, our simulations rely on an implied counterfactual that all other observed process and outcome measures would remain the same in presence of imputed levels of SPS.

Leapfrog has faced prior criticism for employing methods that advantage HSS for hospitals participating in the Leapfrog Hospital Survey in ways unrelated to representations of valid hospital safety.27 This study revealed another way that Leapfrog Hospital Survey participation potentially advantaged hospitals. Rather than use Hospital Compare's publicly-reported CLABSI and CAUTI SIRs for the HSS for all hospitals, these SIRs were only used for hospitals who did not complete the 2013 Leapfrog Hospital Survey; participating hospitals were allowed to use self-reported rates instead. Our comparisons of these self-reported SIRs with the Hospital Compare SIRs found that while CLABSI SIRs were largely similar across data sources for hospitals participating in the Leapfrog Hospital Survey, self-reported CAUTI SIRs were substantially lower than Hospital Compare CAUTI SIRs. This resulted in an advantage for hospitals that participated in the Leapfrog Hospital Survey, as they received credit for a lower SIR; it also disadvantaged hospitals that did not participate in the Leapfrog Hospital Survey by artificially deflating the mean of the distribution with which these hospitals' SIRs were compared.

Improving the Leapfrog HSS

Leapfrog's mission to grade hospitals in a manner that is both methodologically rigorous and results in accessible comparisons is undoubtedly laudable. However, the lack of association between Leapfrog's proprietary, and voluntary, SPS and the compulsory metrics reported on Medicare's Hospital Compare website raises questions about the internal consistency of Leapfrog's HSS. Recent press releases highlighting Fall 2016 Leapfrog grades28, 29 illustrate the Score's two audiences: for consumers attempting reconciliation of safety-related metrics, the HSS offers a comprehensive measure incorporating proprietary process measures and important outcomes; for hospital administrators, an “A” grade from Leapfrog offers consumer-friendly marketing opportunities. For both groups, however, the composite is only meaningful if it is internally consistent—i.e., if process measures correlate in meaningful ways with important outcomes. For consumers, important outcomes reflect personal health needs and concerns; if SPS' do not provide a direct pathway from experience to outcome, its value is unclear. For administrators, important outcomes are increasingly defined by policies that incentivize or penalize certain metrics; SPS that add more noise than signal to composite measures undermine any value-added proposition.

Some of the deficiencies of the Leapfrog HSS have straightforward remedies. For example, Leapfrog should use Hospital Compare's CLABSI and CAUTI SIRs for all hospitals, rather than self-reported rates. Other deficiencies will require Leapfrog to align broader incentive structures with reporting accuracy, rather than opportunity for leniency. In the context of the HSS, where nearly all inputs now stem from compulsory, standardized measures, voluntary SPS self-reports represent a rare locus of hospital control.

Although Leapfrog currently incorporates methods for encouraging data accuracy, including requiring a letter of affirmation and flagging potentially erroneous or misleading reports,30 auditing processes are crucial for ensuring that variation in these measures reflects true differences in process best practice. Just as we would not expect drivers to turn themselves in for speeding, we should not expect hospitals to accurately self-report failure to protocolize safe practices. Leapfrog has recently implemented new efforts to externally validate data,30 which may help to incentivize accurate reporting. As a further step, Leapfrog should consider asking hospitals to report information about the survey completion process, including potential conflicts of interest—for example, which administrators spearheaded Leapfrog survey response? What direct access to clinical practice do they have? And what stake (if any) do they have in the hospital's grade? To the extent that mechanisms of safe practices go beyond minimally-implemented protocols, Leapfrog may also want to consider adding more objective safe practice measures to their survey.

Finally, Leapfrog should ensure that ‘honest’ hospitals are not unfairly disincentivized to report less-than-ideal SPS measures. Given the strongly skewed distributions observed in recent SPS data, methods other than z-scores should be considered for making data commensurate.

Conclusion

In dissecting Leapfrog's Safe Practice Scores and HSS and grades, our study finds little association between self-reported SPS measures and publicly-reported outcomes and penalties data. Further, we find that Leapfrog's current methodologies, in combination with strongly positively skewed self-reports of SPS measures, punish low SPS reports substantially more than they reward high SPS. These concerns cast doubt on the utility of SPS and, more generally, the HSS and grades.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1 (pdf). Flow diagram for study inclusion and model Ns

Supplemental Figure 2 (pdf). Comparison of CLABSI and CAUTI SIRs used in Hospital Safety Score, compared to compulsorily-reported to Hospital Compare, by data source

Supplemental Table 1 (docx). Leapfrog Safe Practice Score measures

Supplemental Table 2 (docx). The Leapfrog Group's Hospital Safety Score Grade: Components, data sources, weights and grade boundaries for Spring 2014

Supplemental Table 3 (docx). Bivariate correlations between Leapfrog Safe Practice Score and outcomes and penalties publicly-reported on Hospital Compare

Supplemental Table 4 (docx). Is there an association between Leapfrog Safe Practices Score (SPS) measures and rates of CLABSI and CAUTI reported by Hospital Compare? Coefficients and 95% confidence intervals from multivariate linear regression models, by SPS measure

Supplemental Table 5 (docx). Is there an association between Leapfrog Safe Practices Score (SPS) measures and penalization under HRRP or HACRP? Coefficients and 95% confidence intervals from multivariate binary logistic regression models, by SPS measure

Supplemental Table 6 (docx). Is there an association between Leapfrog Safe Practices Score (SPS) and HRRP RAF or Total Hospital-Acquired Conditions Score? Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from censored linear regression models, by SPS measure

Acknowledgments

Conflict disclosure: Dr. Meddings has reported receiving honoraria from hospitals and professional societies devoted to complication prevention for lectures and teaching related to prevention and value-based purchasing policies involving catheter-associated urinary tract infection and hospital-acquired pressure ulcers. Dr. Meddings's research has also been recently supported by AHRQ grant P30HS024385, a pilot grant from the University of Michigan's Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center funded by the National Institute on Aging, and grants from the VA National Center for Patient Safety and the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. Dr. Meddings's research is also supported by contracts with the Health Research & Education Trust (HRET) involving the prevention of CAUTI in the acute-care and long-term care settings that are funded by AHRQ, the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Dr. Meddings was also a recipient of the 2009–2015 National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Loan Repayment Program.

Footnotes

Funding disclosure: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality K08HS19767, 2R01HS018334

Dr. Smith, Ms. Reichert, and Ms. Ameling have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Shawna N. Smith, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School, 2800 Plymouth Rd., Building 16, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, Phone: 734-763-4431, Fax: 734-936-8944

Heidi Reichert, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School, 2800 Plymouth Rd., Building 16, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, Phone: 734-615-8591, Fax: 734-936-8944

Jessica Ameling, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School, 2800 Plymouth Rd., Building 16, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, Phone: 734-764-2096, Fax: 734-936-8944

Jennifer Meddings, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School, 2800 Plymouth Rd., Building 16, Room 430W, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, Phone: 734-936-5216, Fax: 734-936-8944

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital Compare. [Accessed April 8, 2016]; Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/

- 2.The Leapfrog Group. [Accessed March 30, 2016];2016 Available at: http://www.leapfroggroup.org/

- 3.Austin JM, D'Andrea G, Birkmeyer JD, et al. Safety in numbers: the development of Leapfrog's composite patient safety score for U.S. hospitals. J Patient Saf. 2014;10:64–71. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3182952644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Safe Practices for Better Healthcare–2010 Update: A Consensus Report. National Quality Forum; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hospital Safety Score. Scoring Methodology. 2014 Available at: http://www.hospitalsafetyscore.org/media/file/HospitalSafetyScore_ScoringMethodology_Spring2014_Final.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2016.

- 6.Hospital Safety Score. [Accessed April 20, 2016];2015 Available at: http://www.hospitalsafetyscore.org/

- 7.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services' Hospital Compare. Hospital Quality Initiative: Hospital Compare. [Accessed April 14, 2016]; Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/HospitalCompare.html.

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. HCAHPS: Patients' Perspectives of Care Survey. [Accessed May 3, 2016];2014 Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-instruments/HospitalQualityInits/HospitalHCAHPS.html.

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) [Accessed April 14, 2016];2016 Available at: http://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html.

- 10.QualityNet. Hospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) Reduction Program. [Accessed March 30, 2016]; Available at: http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier2&cid=1228774189166.

- 11.Ghaferi AA, Osborne NH, Dimick JB. Does voluntary reporting bias hospital quality rankings? J Surg Res. 2010;161:190–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Ridgway AB, et al. Does the Leapfrog program help identify high-quality hospitals? Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:318–325. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Potential benefits of the new Leapfrog standards: effect of process and outcomes measures. Surgery. 2004;135:569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kernisan LP, Lee SJ, Boscardin WJ, et al. Association between hospital-reported Leapfrog Safe Practices Scores and inpatient mortality. JAMA. 2009;301:1341–1348. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qian F, Lustik SJ, Diachun CA, et al. Association between Leapfrog safe practices score and hospital mortality in major surgery. Med Care. 2011;49:1082–1088. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318238f26b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glance LG, Dick AW, Osler TM, et al. Relationship between Leapfrog Safe Practices Survey and outcomes in trauma. Arch Surg. 2011;146:1170–1177. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; [Accessed September 14, 2015]. Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program. [database online] Updated 2015. Available at: http://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/HAC-reduction-program.html. [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Healthcare Safety Network e-News; Your Guide to the Standardized Infection Ratio (SIR) [Accessed March 30, 2016];2010 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/Newsletters/NHSN_NL_OCT_2010SE_final.pdf.

- 19.Dudeck MA, Horan TC, Peterson KD, et al. National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) report, data summary for 2009, device-associated module. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39:349–367. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dudeck MA, Edwards JR, Allen-Bridson K, et al. National Healthcare Safety Network report, data summary for 2013, device-associated module. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43:206–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Healthcare Safety Network. Bloodstream Infection Event January 2016 (Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection and non-central line-associated Bloodstream Infection) [Accessed March 30, 2016];2016 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/pscManual/4PSC_CLABScurrent.pdf.

- 22.Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; [Accessed April 13, 2015]. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program Penalty. [database online] Updated 2015. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Downloads/FY2015-FR-Readmit-Supp-Data-File.zip. [Google Scholar]

- 23.StataCorp. Stata Stastical Sofware: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Explanation of Safety Score Grades. [Accessed July 12, 2016];2014 Hospital Safety Score. Available at: http://www.hospitalsafetyscore.org/media/file/ExplanationofSafetyScoreGrades_April2014.pdf.

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare Associated Infections: Progress Report. [Accessed April 6, 2016];2016 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/stateplans/factsheets/us.pdf.

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Paving the Path Forward: 2015 Rebaseline. [Accessed December 22, 2016]; Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/2015rebaseline/

- 27.Hwang W, Derk J, LaClair M, et al. Hospital patient safety grades may misrepresent hospital performance. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:111–115. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greene J. Leapfrog Survey: Michigan Hospitals Improve in Patient Safety. [Accessed January 5, 2017];2016 Available at: http://www.crainsdetroit.com/article/20161031/NEWS/161029813/leapfrog-survey-michigan-hospitals-improve-in-patient-safety.

- 29.Whitman E. Leapfrog releases latest hospital safety grades. [Accessed December 22, 2016];2016 Available at: http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20161031/NEWS/161039998.

- 30.The Leapfrog Group. Ensuring Data Accuracy. [Accessed April 20, 2016]; Available at: http://www.leapfroggroup.org/survey-materials/ensuring-data-accuracy.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1 (pdf). Flow diagram for study inclusion and model Ns

Supplemental Figure 2 (pdf). Comparison of CLABSI and CAUTI SIRs used in Hospital Safety Score, compared to compulsorily-reported to Hospital Compare, by data source

Supplemental Table 1 (docx). Leapfrog Safe Practice Score measures

Supplemental Table 2 (docx). The Leapfrog Group's Hospital Safety Score Grade: Components, data sources, weights and grade boundaries for Spring 2014

Supplemental Table 3 (docx). Bivariate correlations between Leapfrog Safe Practice Score and outcomes and penalties publicly-reported on Hospital Compare

Supplemental Table 4 (docx). Is there an association between Leapfrog Safe Practices Score (SPS) measures and rates of CLABSI and CAUTI reported by Hospital Compare? Coefficients and 95% confidence intervals from multivariate linear regression models, by SPS measure

Supplemental Table 5 (docx). Is there an association between Leapfrog Safe Practices Score (SPS) measures and penalization under HRRP or HACRP? Coefficients and 95% confidence intervals from multivariate binary logistic regression models, by SPS measure

Supplemental Table 6 (docx). Is there an association between Leapfrog Safe Practices Score (SPS) and HRRP RAF or Total Hospital-Acquired Conditions Score? Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from censored linear regression models, by SPS measure