Abstract

Peripheral nerve sheath tumors (PNSTs) are known to occur in the orbit and comprise 4% of all orbital tumors, but have not been well-studied in contemporary literature. Ninety specimens involving the eye and ocular adnexa (1979–2015) from 67 patients were studied. The mean age was 32.5 years. Locations included orbit (58.9%), eyelid (60.0%) and other ocular adnexa. A large majority of specimens were neurofibromas (70.0%), followed by schwannomas (11.1%), neuromas (11.1%), granular cell tumors (n=4), nerve sheath myxomas (n=2), and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (n=1). Fifty-six (88.9%) neurofibroma cases were neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1)-associated. Among neurofibromas, 31.7% were localized, 38.1% were plexiform, 25.4% were diffuse, and 4.8% were diffuse and plexiform. These tumors involved skin (31.7%), soft tissue (11.1%), skeletal muscle (22.2%), peripheral nerve (63.0%), lacrimal gland (20.6%) and choroid (n=1). Other histologic findings included pseudo-Meissner corpuscles (27%), Schwann cell nodules (4.8%), prominent myxoid component (7.9%), melanin-like pigment (3.2%), and inflammation (14.3%). Available immunostains included S100 (+ in 15/15 cases), EMA (+ in 2/4 cases), CD34 (+ in 4/4 cases), and Ki67 (<1% in 4/4 cases). Among 10 schwannomas, 8 were conventional and 2 were plexiform. Observed features included capsule (n=5), hyalinized vessels (n=5), Verocay bodies (n=7), and Antoni B pattern (n=5). Immunostaining included S100+ in 4/4 cases, collagen IV+ and Ki67<1% in 3/3 cases. Neurofibromas are the most common PNST involving the eye and ocular adnexa and the majority are associated with NF1. Plexiform and diffuse patterns and the presence of pseudo-Meissner corpuscles are relatively frequent in this area.

Keywords: peripheral nerve sheath tumor, orbit, ocular, neurofibroma, schwannoma

1 INTRODUCTION

Peripheral nerve sheath tumors (PNSTs) are common soft tissue and cutaneous neoplasms, but only comprise approximately 4% of all orbital tumors [1]. These tumors are thought to originate from sensory nerves in the orbit and are most frequently located in the superior and medial orbital compartments. The most common PNST of the orbit is neurofibroma [1, 2], which can be classified as plexiform, diffuse, or localized; 2% of orbital tumors are plexiform neurofibromas frequently associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and 1% are isolated neurofibromas. The remaining PNSTs are schwannomas, the next most common type at this site. In addition, other rare PNSTs of the orbit such as neuroma, granular cell tumor (GCT), nerve sheath myxoma (NSM), and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) have been described.

To our knowledge, the largest case review of PNSTs of the orbit included 54 cases of neurofibromas, schwannomas, and MPNSTs; however, this study included only clinical information with no comprehensive pathologic analysis [3]. Neurofibroma-specific studies included a review of 13 patients with plexiform neurofibromas of the eye region with particular attention to cases in patients without NF1 [4] and multiple single case reports [5–8]. Given their rarity, there have been small clinicopathologic studies of orbital MPNSTs from 1985 (8 cases) [9] and 1989 (3 cases) [10], but only single case reports in more recent literature [11–13]. Similarly, the largest report of 7 orbital schwannoma cases with histology was from 1982 [14], whereas only single case reports have been published in the past decade [15–20]. Similarly, there has been a review of 19 cases of GCT in 1983 [21] and a literature survey performed in 2011 of 39 reported cases [22]. In contrast, we only found descriptions of a few cases of amputation neuromas [23, 24] and one case report of an orbital NSM with histopathologic examination [25].

Thus, in recent literature, orbital PNSTs have not been well-studied and have primarily been described on a clinical case-by-case basis. In this study, we performed a comprehensive histopathologic review of all orbital PNST cases seen at our institution between 1979–2015, and classified them using contemporary diagnostic histopathologic criteria.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pathology reports from the Eye Pathology Laboratory and the electronic Pathology Data System of The Johns Hopkins Hospital were searched for PNSTs involving the orbit and ocular adnexa, with identified specimens spanning from 1979 to 2015. The following search terms were used: neurofibroma, schwannoma, nerve sheath myxoma, plexiform, neurofibrosarcoma, MPNST, neuroma, neurothekeoma, perineurioma, and granular cell tumor. Surgical pathology reports were individually reviewed to identify only cases involving the orbit and ocular adnexa. Clinicopathologic information (including patient age, sex, race, and prior medical history) and follow-up information regarding clinical, imaging, operative, and surgical pathology reports were recorded, if available. All histopathologic slides and special stains performed were reviewed and their morphological features were recorded. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Johns Hopkins Medicine, and all the recommended ethical guidelines were followed.

2.1 Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12.1.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Patient Demographics and History

A total of 90 specimens from 67 patients were identified (Table 1). The mean (SD) age was 32.5 (24.8) years and 52.2% were female (47/90). Fifty-one of 90 (56.7%) were white, 26 (28.9%) were black. The most common location of PNSTs was the orbit (37.8%), followed by the eyelid (36.7%) and both the eyelid and orbit (18.9%). Forty-nine of 90 (54.4%) tumors were surgically removed via gross total resection (GTR), 31 (34.4%) via subtotal resection (STR), and 7 (7.8%) were biopsies. The mean (SD) recurrence-free survival (RFS) of GTR tumors, defined as the number of years between the operation date and the first tumor recurrence or death, was 5.3 (5.0) years. The minimum RFS was 0.25 years, and the maximum RFS was 16 years, which was a neuroma case where the patient died due to reasons unrelated to the tumor.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and History of Identified Specimens

| Total (%), n=90a | Neurofibrom a (%), n=63 | Schwannom a (%), n=10 | Neurom a (%), n=10 | GCT (%), n=4 | Myxoma (%), n=2 | MPNS T (%), n=1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) Age | 32.5 (24.8) | 26.5 (20.9) | 50.1 (24.5) | 48.4 (24.8) | 57.3 (28.3) | 57.0 (7.1) | 62 (N/A) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 43 (47.8) | 32 (50.8) | 3 (30.0) | 4 (40.0) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (100) | 0 |

| Female | 47 (52.2) | 31 (49.2) | 7 (70.0) | 6 (60.0) | 2 (50.0) | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 51 (56.7) | 36 (57.1) | 7 (70.0) | 6 (60.0) | 2 (50.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Black | 26 (28.9) | 20 (31.7) | 1 (10.0) | 2 (20.0) | 2 (50.0) | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Other | 6 (6.7) | 5 (7.9) | 0 | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 7 (7.8) | 2 (3.2) | 2 (20.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 2 (100) | |

| Tumor Location | |||||||

| Orbit | 34 (37.8) | 21 (33.3) | 6 (60.0) | 2 (20.0) | 4 (100.0%) | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Eyelid | 33 (36.7) | 21 (33.3) | 3 (30.0) | 8 (80.0) | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 0 |

| Conjunctiva | 2 (2.2) | 0 | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 0 |

| Eyelid and orbit | 17 (18.9) | 17 (27.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Eyelid and conjunctiva | 2 (2.2) | 2 (3.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Eyelid, orbit, conjunctiva | 2 (2.2) | 2 (3.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Extent of Resection | |||||||

| Gross total resection | 49 (54.4) | 28 (44.4) | 8 (80.0) | 8 (80.0) | 3 (75.0) | 2 (100) | 0 |

| Subtotal resection | 31 (34.4) | 28 (44.4) | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Biopsy | 7 (7.8) | 4 (6.3) | 1 (10.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 3 (3.3) | 3 (4.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Recurrence-free Survival (y) | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.5 (4.3) | 3.2 (3.8)b | 13.3 (N/A)c | 16 (N/A)d | 1.8 (1.9)e | Unknown | 0.5 (N/A) |

| Range (min, max) | 0, 16 | 0, 14.5 | 0.5, 4 | Unknown |

Abbreviations: GCT, granular cell tumor; MPNST, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

There are n=67 unique individuals, and n=23 have multiple specimens.

Patient alive without recurrence (n=14), unknown follow-up (n=10).

Patient died without recurrence (n=1), patient alive without recurrence (n=6), unknown follow-up (n=3).

Patient died without recurrence (n=1), patient alive without recurrence (n=5), unknown follow-up (n=4).

Unknown follow-up (n=1).

Of all the PNSTs, 70.0% (63/90) were neurofibromas, 11.1% (10/90) were schwannomas, 11.1% (10/90) were neuromas, 4.4% (4/90) were granular cell tumors (GCT), 2.2% (2/90) were nerve sheath myxomas, and one case was a MPNST. A total of 63 specimens from 42 patients were neurofibromas. The mean (SD) age of the neurofibroma specimens was 26.5 (20.9) years; 49.2% (31/63) were female, 57.1% (36/63) were white, and 31.7% (20/63) were black. An equal number of neurofibromas were located in the orbit and eyelid (33.3% each), with 27.0% of tumors extending through the eyelid and the orbit. Similarly, an equal number were excised via GTR and STR (44.4% each) and 6.3% were biopsies. The mean (SD) RFS of patients with a GTR neurofibroma was 4.5 (4.2) years. The minimum RFS was 0.25 years and the maximum was 14.5 years; 22.2% (14/63) of patients are alive without tumor recurrence. In the neurofibroma subgroup, there was no significant difference in RFS with respect to the neurofibroma subtype (p=0.13).

3.2 Neurofibromas

The morphological features of neurofibromas are summarized in Table 2. Examples of these features are shown in Figures 1 and 2. A total of 38.1% (24/63) were predominantly plexiform, 31.7% (20/63) were localized, 25.4% (16/63) were predominantly diffuse, and 4.8% (3/63) were diffuse and plexiform neurofibromas. Approximately half had some diffuse and some plexiform components, and 63.0% were associated with recognizable nerves. In addition, there was tumor involvement of the skin (31.7%), muscle (22.2%), and lacrimal gland (20.6%). A total of 27.0% (17/63) of specimens contained pseudo-Meissnerian corpuscles. A few specimens contained Schwann cell nodules (3/63), a myxoid component (5/63), and pigment (2/63), respectively. 4/63 (6.3%) were circumscribed. Immunohistochemical stains were originally performed in 18/63 (28.6%) cases: S100 was positive in 15/15 cases, EMA was positive in 2/4 cases, CD34 was positive in 4/4 cases, and Ki67 was <1% in 4/4 cases.

TABLE 2.

Morphological Features of Neurofibromas of the Ocular Adnexa

| Total (%), n=63a | NF1 (%), n=56 | |

|---|---|---|

| Subtype | ||

| Conventional | 20 (31.7) | 15 (26.8) |

| Plexiform | 24 (38.1) | 23 (41.1) |

| Diffuse | 16 (25.4) | 15 (26.8) |

| Diffuse and plexiform | 3 (4.8) | 3 (5.4) |

| Features | ||

| Diffuse component | 33 (52.4) | 31 (55.4) |

| Plexiform component | 33 (52.4) | 31 (55.4) |

| Skin involvement | 20 (31.7) | 20 (35.7) |

| Soft tissue involvement | 7 (11.1) | 6 (10.7) |

| Muscle involvement | 14 (22.2) | 13 (23.2) |

| Nerve association | 42 (63.0) | 39 (69.6) |

| Lacrimal gland association | 13 (20.6) | 13 (23.2) |

| Pseudo-Meissner corpuscles | 17 (27.0) | 16 (28.6) |

| Schwann cell nodules | 3 (4.8) | 3 (5.4) |

| Hypercellularity | 2 (3.2) | 1 (1.8) |

| Inflammation | 9 (14.3) | 8 (14.3) |

| Foreign body reaction | 2 (3.2) | 2 (3.6) |

| Myxoid component | 5 (7.9) | 4 (7.1) |

| Pigment | 2 (3.2) | 2 (3.6) |

| Circumscribed | 4 (6.3) | 4 (7.1) |

| Stains performed | 18 (28.6) | 15 (26.8) |

Abbreviations: NF1, neurofibromatosis 1

There are n=42 unique individuals, and n=21 have multiple specimens.

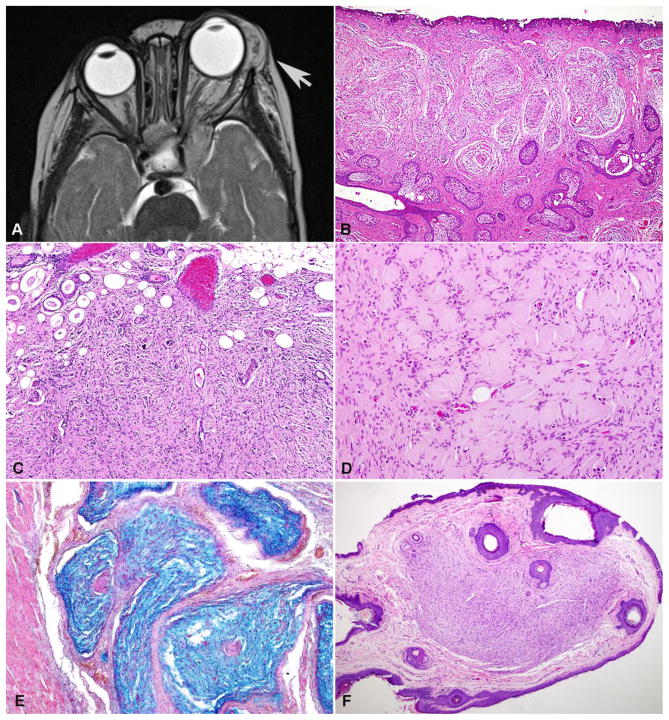

Figure 1. Clinicopathologic features of neurofibromas of the ocular adnexa.

T2-weighted MRI of a left orbital neurofibroma in a patient with NF1 (arrow)(A). Plexiform (B) and diffuse (C) patterns of growth were particularly prevalent in these patients. Pseudomeissnerian corpuscles were frequent in diffuse neurofibromas of these patients (D). Alcian blue special stain particularly highlights the plexiform patterns of growth (E). Circumscribed cutaneous neurofibromas involving the eyelid were also present (F).

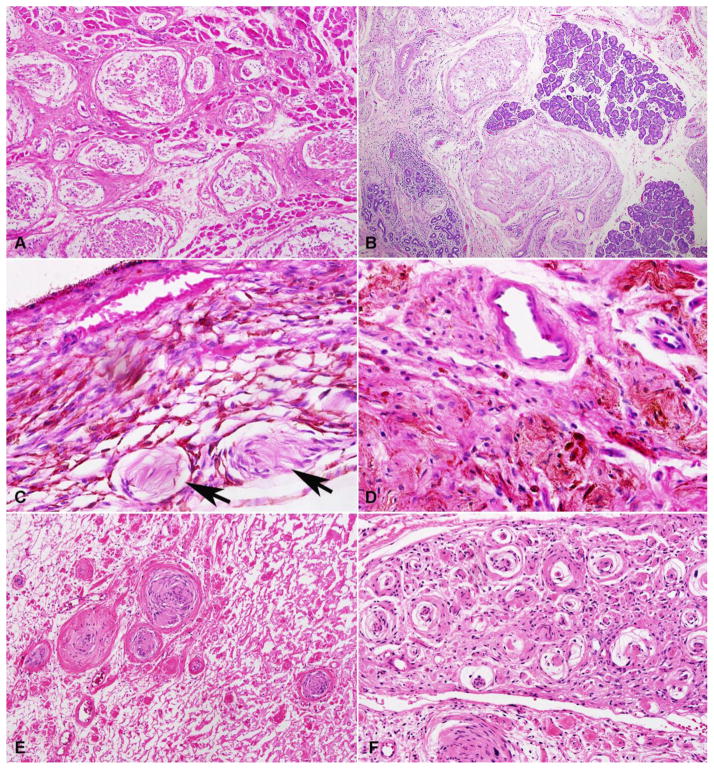

Figure 2. Histopathologic features of neurofibromas of the ocular adnexa.

A subset of plexiform neurofibromas were large and involved deep periocular structures, including skeletal muscle (A) and lacrimal gland (B). Focal involvement of intraocular structures, specifically the choroid (arrows), was rare (C). Rare histologic findings included pigmentation (D), schwannian nodules (E), and pseudo-onion bulbs (F).

In the ocular neurofibroma group, 88.9% (56/63) were associated with NF1. Overall, the frequency of features in this subgroup was similar to the total. 41.1% (23/56) were plexiform neurofibromas, and 26.8% (15/56) were localized and diffuse neurofibromas, respectively. Over half of specimens had diffuse and plexiform components, respectively, and 69.6% (39/56) were associated with nerves. Sixteen of 56 (28.6%) specimens contained pseudo-Meissnerian corpuscles.

A single neurofibroma with malignant transformation (MPNST) was identified in our group. In brief, a 63-year-old woman satisfying diagnostic criteria for NF1, developed a progressive low grade MPNST arising in a diffuse/plexiform neurofibroma present since childhood. The patient died subsequently with leptomeningeal dissemination. Detailed clinicopathologic features have been reported elsewhere [26].

3.3 Schwannomas

Morphological features of schwannomas upon slide review are illustrated and summarized in Figure 3 and Table 3. Eight of 10 were conventional and 2/10 were plexiform schwannomas. Half of the specimens were encapsulated, contained hyalinized vessels, and had some component of Antoni B pattern (highest was 50%). Seven of 10 contained Verrocay bodies. Immunohistochemical stains were originally performed in 4/10 cases: S100 was positive in 4/4 cases, collagen IV was positive in 3/3 cases and Ki67 was <1% in 3/3 cases.

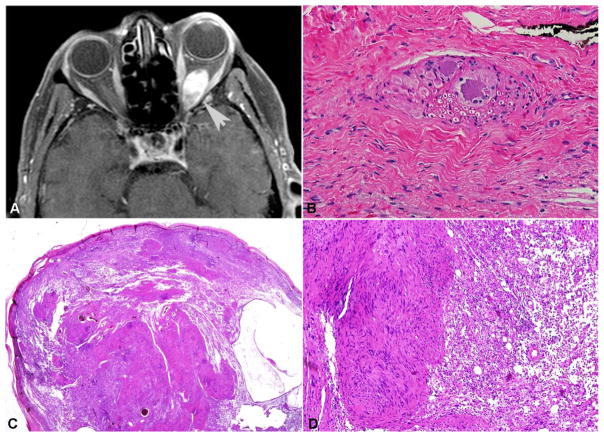

Figure 3. Clinicopathologic features of periocular schwannomas.

In contrast to neurofibromas, orbital schwannomas formed well circumscribed masses (arrow, T1 weighted MRI with contrast) (A). This particular case developed in association with the ciliary ganglion, explaining the presence of residual ganglion cells (B). Conventional periocular schwannoma with a capsule, Antoni A pattern with Verocay bodies, and Antoni B pattern with loose stroma. (C, D)

TABLE 3.

Morphological Features of Schwannomas of the Ocular Adnexa

| Total (%), n=10 | |

|---|---|

| Subtype | |

| Conventional | 8 |

| Plexiform | 2 |

| Features | |

| Plexiform component | 2 |

| Capsule | 5 |

| Hyalinized vessels | 5 |

| Nerve association | 2 |

| Verrocay bodies | 7 |

| Antoni B patterna | 5 |

| Stains performed | 4 |

Antoni B pattern (n=5): <5%, <10%, 10%, 30%, 50%

3.4 Neuromas

Of the neuromas, 5/10 were traumatic, 2/10 were palisaded encapsulated neuromas (PENs), and 3/10 were not otherwise specified (NOS). Specimens contained localized aggregates of spindle-shaped cells within dense fibrous connective tissue and disorganized bundles of normal-appearing peripheral nerve (Figures 4A and 4B). Both PENs had pericellular collagen IV labeling and bland spindle cells that were positive for S100. The other PEN was a nodule in the deep dermis composed predominantly of bland Schwann cells and associated with a small nerve branch. It had S100 and SOX10 co-expression in Schwann cells, and neurofilament protein (SM31) highlighted intralesional axons. One neuroma NOS involved skin and nerve, with S100 labeling Schwann cells, EMA outlining the perineurium of nerve twigs, SM31 labeling axons, and Ki67 labeling index <1%.

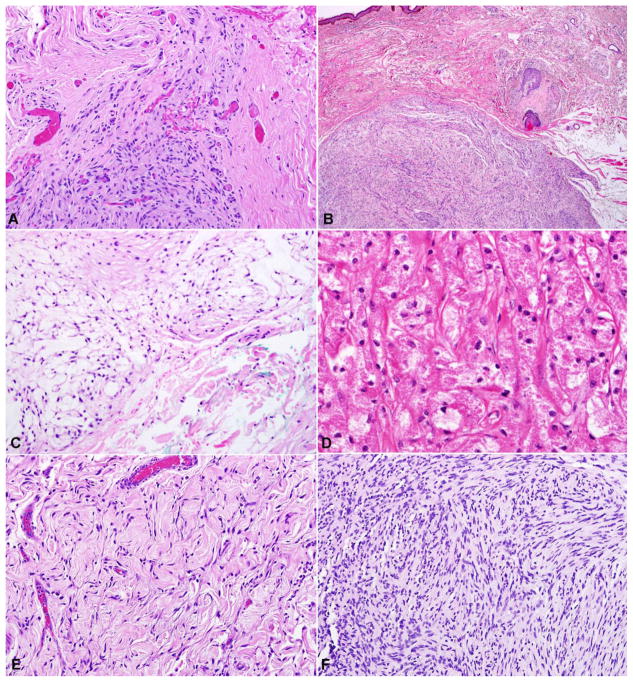

Figure 4. Pathologic features of uncommon nerve sheath lesions involving periocular structures.

Other nerve sheath lesions that may involve periocular structures included traumatic neuroma in the setting of trauma or prior surgical intervention (A). Palisaded encapsulated neuroma was often associated with small nerve branches in the eyelid (B). Nerve sheath myxomas are composed of bland spindle cells in a myxoid matrix (C) with associated S100 expression (not shown). Granular cell tumor composed of large cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm (D). The single low-grade malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor developed from a diffuse/plexiform neurofibroma (E), and was characterized by areas of hypercellularity and atypia (F).

3.5 Granular Cell Tumors (GCTs)

Two cases of GCT were from the same patient. This 71-year-old woman first presented with one month of swelling at the left inferior orbital rim. Her tumor was removed and found to be composed of large cells with small nuclei, eosinophilic granular cytoplasm, blood vessels, foci of chronic inflammation, and loose connective tissue matrix (Figure 4D). S100 was uniformly positive and the cytoplasmic granules were PAS+. Four years later, the patient developed ptosis of the left eye with superolateral deviation of the globe. Her recurrent GCT had similar cellular features with degenerative changes and dense fibrous connective tissue.

An atypical GCT case was seen in a 68-year-old man with a history of recurrent left inferior orbital GCT. Intraoperative exploration revealed tumor extensively involving the inferomedial orbit; only subtotal resection could be performed (Table 1). Histologic examination showed rare cells with PAS+ granules, focal perineural invasion, and focal necrosis. The tumor cells stained strongly for S100 and were negative for cytokeratins AE1/3 and HMB45. The Ki67 index was approximately 10%. On follow-up, the patient had become blind in the left eye and the tumor appeared to extend into the ethmoid sinuses.

Lastly, we saw a relentless case of GCT in a 15-year-old male who first presented with intermittent headaches and sudden-onset pain behind his right eye in. CT scan showed a right superior orbital mass displacing the right optic nerve inferiorly. Following a subtotal resection and subsequent recurrence, the mass was finally completely resected and histopathologic examination showed cytologically bland cells with PAS+ cytoplasmic granules. Immunostaining was positive for S100 and focally positive for CD68.

3.6 Ocular Nerve Sheath Myxomas (NSM)

These two cases of ocular NSM (located in the conjunctiva and eyelid, respectively) were composed of small spindle cells dispersed uniformly in a light myxoid matrix (Figure 4C). They were positive for S100, CD34, SM31 in associated nerve twigs, and weakly positive for SOX10 in rare cells. The Ki67 proliferation index was near 0%. The tumors were negative for cytokeratins AE1/3 and CAM 5.2. Both patients were lost to follow-up.

4 DISCUSSION

Although multiple studies have clinically described features of orbital peripheral nerve sheath tumor (PNST) cases, the literature is predominated by single cases without focused histopathologic examination of these tumors. We undertook a comprehensive histopathologic review of many PNSTs from the orbit and ocular adnexa in the context of current classifications.

In this study, 70% were neurofibromas, and the majority were associated with a history of NF1. Common characteristics seen in these tumors included nerve association in over 60% of cases, pseudo-Meissnerian corpuscles, and skin/muscle/lacrimal gland involvement. Historically, plexiform neurofibromas were thought to be virtually pathognomonic for NF1. However, Bechtold et al [4] reported a case series where 3/13 patients with plexiform neurofibromas of the periocular region did not have NF1. In our larger series, 96% (23/24) of plexiform neurofibromas were NF1-associated, suggesting that this is a much more common, albeit not completely pathognomonic, association than previously reported with these tumors in the ocular adnexa. It must be noted that some patients may have NF1 gene inactivation limited to one anatomic region (i.e. segmental neurofibromatosis), and in theory patients without other clinical manifestations of NF1 may fall within this group. Molecular genetic analysis may be helpful in characterizing this phenomenon.

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) of the orbit are extremely rare, with only a quarter or less associated with NF1 [9]. Interestingly, Jakobiec et al [9] found a tendency for MPNSTs to arise from the supraorbital nerve in the anterior superior orbit, as reported in this older series of eight cases. One important caveat is that desmoplastic/neurotropic melanoma is a known mimic of MPNST, and much more common in the head and neck region.

The largest case series to our knowledge [3] reported that benign neurofibromas and schwannomas had equal incidence; however, in our survey only 11% of all orbital PNSTs were schwannomas. Half of the schwannoma specimens displayed previously described classic features [2, 14], including a capsule, hyalinized vessels, and coexisting Antoni A and Antoni B patterns. Most schwannomas of the orbit appear to be sporadic, but some have occurred in association with NF2 [27]. We did not see that association in any of the cases in this study.

Postamputation neuromas are known mimickers of neurofibromas [2]. However, they exhibit a distinct histological appearance as described by Messmer et al. in 1984, including cystic structures with irregular tangles and whorls composed of disorganized axons, Schwann cells, and connective tissue [23]. Subsequent case reports have described similar histopathologic features, with most occurring following enucleation or transection of the optic or ciliary nerve [24, 28]. In addition to traumatic neuromas, we also reviewed two palisaded encapsulated neuromas (PENs), which were composed of bland spindle cells positive for S100. There have been four cases of eyelid PENs reported in the literature to our knowledge, all of which presented as painless solid nodules in patients over 40 years old [29–31]. They each described the histology of the lesion as numerous fascicles of spindle-shaped cells with a characteristic palisading pattern that is surrounded by a thin fibrous capsule. These masses were composed of a mixture of S100+ Schwann cells and scattered neurofilament positive nerve fibers, and EMA highlighted perineural cells forming the capsule. PENs were often misdiagnosed clinically as dermatologic lesions or neurofibromas, and were only distinguishable on histopathologic examination.

Sanchez-Orgaz et al [25] published a report of an orbital nerve sheath myxoma (NSM) in the lateral orbital margin of the eye, which was described as a tumor composed of myxoid nodules separated by fibrous septa with spindle cells admixed with abundant myxoid matrix. Many cells were positive for S100 and EMA, and the proliferation index was <1%. Our study adds two more cases, both of which contained spindle cells dispersed in a myxoid or mucinous background. Similarly, S100 was positive and there was no detectable mitotic activity.

Ribeiro et al [22] recently reported a case of an orbital granular cell tumor (GCT) along with a literature survey of 39 historically reported cases. GCTs are frequently associated with extraocular muscles, most commonly in the inferior aspect of the orbit affecting the inferior and medial rectus muscles. They were composed of polygonal cells arranged in nests and clusters with abundant granular PAS-positive cytoplasm, as well as S100 and CD68 positivity. All of these characteristics are consistent with the cases reviewed in this study; only 1/4 GCTs involved the superior orbit.

In the present series, we did not identify any cases of eyelid submucosal neuromas, which are rare but characteristic of multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 2B syndrome. Ophthalmic manifestations generally do not cause clinically significant visual disturbances, but are frequently the initial presentation of this syndrome. A review of 33 MEN2B cases since 1966 reported eyelid neuromas and subconjunctival neuromas in 88% and 79% of patients, respectively [32]. Thus, identification of these ocular tumors can permit the early diagnosis of MEN2B and importantly, the early treatment of associated medullary thyroid carcinomas and pheochromocytomas.

In summary, the majority of PNSTs in our study were neurofibromas, and a plexiform component was frequent. While most neurofibromas were associated with NF1, there was not an appreciable difference between the plexiform and diffuse subtypes. Malignant degeneration appears to be extraordinarily rare in the orbit or eyelid, with only a single case developing malignant changes in our study. Other nerve sheath tumors were relatively uncommon, but the whole spectrum of nerve sheath neoplasia may be encountered in this area.

Clinicopathologic features of 90 nerve sheath tumors involving the eye and ocular adnexa were studied

Neurofibroma was the predominant histologic type

Most neurofibromas were NF1-associated and had frequent plexiform and diffuse components

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: This work was supported in part by a collaborative grant between the Wilmer Eye Institute (Baltimore, MD) and the King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Font RL, Croxatto JO, Rao NA. Tumors of the Eye and Ocular Adnexa. Washington D.C: American Registry of Pathology in collaboration with the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carroll GS, Haik BG, Fleming JC, Weiss RA, Mafee MF. Peripheral nerve tumors of the orbit. Radiol Clin North Am. 1999;37(1):195–202. xi–xii. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(05)70087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rose GE, Wright JE. Isolated peripheral nerve sheath tumours of the orbit. Eye (Lond) 1991;5(Pt 6):668–673. doi: 10.1038/eye.1991.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bechtold D, Hove HD, Prause JU, Heegaard S, Toft PB. Plexiform neurofibroma of the eye region occurring in patients without neurofibromatosis type 1. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28(6):413–415. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3182627ea1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shields JA, Shields CL, Lieb WE, Eagle RC. Multiple orbital neurofibromas unassociated with von Recklinghausen’s disease. Arch Ophthalmol (Chicago, Ill 1960) 1990;108(1):80–83. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070030086034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee LR, Gigantelli JW, Kincaid MC. Localized neurofibroma of the orbit: a radiographic and histopathologic study. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;16(3):241–246. doi: 10.1097/00002341-200005000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berney C, Spahn B, Oberhansli C, Uffer S, Borruat F-X. Multiple intraorbital neurofibromas: a rare cause of proptosis. Klin Monatsblätter für Augenheilkd. 2004;221(5):418–420. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-812817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeuchi S, Wada K, Nagatani K, Nawashiro H. Localized neurofibromas in the bilateral orbits. Indian J Surg. 2013;75(5):407–408. doi: 10.1007/s12262-012-0501-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jakobiec FA, Font RL, Zimmerman LE. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the orbit: a clinicopathologic study of eight cases. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1985;83:332–366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyons CJ, McNab AA, Garner A, Wright JE. Orbital malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73(9):731–738. doi: 10.1136/bjo.73.9.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Briscoe D, Mahmood S, O’Donovan DG, Bonshek RE, Leatherbarrow B, Eyden BP. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in the orbit of a child with acute proptosis. Arch Ophthalmol (Chicago, Ill 1960) 2002;120(5):653–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dutton JJ, Tawfik HA, DeBacker CM, Lipham WJ, Gayre GS, Klintworth GK. Multiple recurrences in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the orbit: a case report and a review of the literature. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;17(4):293–299. doi: 10.1097/00002341-200107000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajabi MT, Riazi H, Hosseini SS, et al. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of lacrimal nerve: a case report. Orbit. 2015;34(1):41–44. doi: 10.3109/01676830.2014.959610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rootman J, Goldberg C, Robertson W. Primary orbital schwannomas. Br J Ophthalmol. 1982;66(3):194–204. doi: 10.1136/bjo.66.3.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kron M, Bohnsack BL, Archer SM, McHugh JB, Kahana A. Recurrent orbital schwannomas: clinical course and histopathologic correlation. BMC Ophthalmol. 2012;12:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-12-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagashima H, Yamamoto K, Kawamura A, Nagashima T, Nomura K, Yoshida M. Pediatric orbital schwannoma originating from the oculomotor nerve. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2012;9(2):165–168. doi: 10.3171/2011.11.PEDS1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rato RMF, Correia M, Cunha JP, Roque PS. Intraorbital abducens nerve schwannoma. World Neurosurg. 2012;78(3–4):375, e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mortuza S, Esmaeli B, Bell D. Primary intraocular ancient schwannoma: a case report and review of the literature. Head Neck. 2014;36(4):E36–8. doi: 10.1002/hed.23329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feichtinger M, Reinbacher KE, Pau M, Klein A. Intraorbital schwannoma of the abducens nerve: case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71(2):443–445. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kauser H, Rashid O, Anwar W, Khan S. Orbital oculomotor nerve schwannoma extending to the cavernous sinus: a rare cause of proptosis. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2014;9(4):514–516. doi: 10.4103/2008-322X.150833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karcioglu ZA, Hemphill GL, Wool BM. Granular cell tumor of the orbit: case report and review of the literature. Ophthalmic Surg. 1983;14(2):125–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ribeiro SFT, Chahud F, Cruz AAV. Oculomotor disturbances due to granular cell tumor. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28(1):e23–7. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3182141c54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Messmer EP, Camara J, Boniuk M, Font RL. Amputation neuroma of the orbit. Report of two cases and review of the literature. Ophthalmology. 1984;91(11):1420–1423. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okubo K, Asai T, Sera Y, Okada S. A case of amputation neuroma presenting proptosis. Ophthalmologica. 1987;194(1):5–8. doi: 10.1159/000309725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sánchez-Orgaz M, Grabowska A, Arbizu-Duralde A, et al. Orbital nerve sheath myxoma: a case report. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27(4):e106–8. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181f29e74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez EF, Blakeley J, Langmead S, et al. Low grade Schwann cell neoplasms with leptomeningeal dissemination: clinicopathologic and autopsy findings. Hum Pathol. 2016 Sep; doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiratli H, Yildiz S, Soylemezoğlu F. Neurofibromatosis type 2: optic nerve sheath meningioma in one orbit, intramuscular schwannoma in the other. Orbit. 2008;27(6):451–454. doi: 10.1080/01676830802350356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glasgow BJ, Vinters HV, Foos RY. Traumatic neuroma of the eyelid associated with ptosis. [Accessed October 1, 2016];Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990 6(4):269–272. doi: 10.1097/00002341-199012000-00008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2271484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dubovy SR, Clark BJ. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma (solitary circumscribed neuroma of skin) of the eyelid: report of two cases and review of the literature. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(8):949–951. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.8.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Messner KS, Braniecki M. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma: an entity to consider in the differential diagnosis of the eyelid nodule. A case report. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27(2):e35–7. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181d1aadb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Surapaneni KR, Phelps PO, Potter HD. Palisaded Encapsulated Neuroma of the Eyelid. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(8):1554. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobs JM, Hawes MJ. From eyelid bumps to thyroid lumps: report of a MEN type IIb family and review of the literature. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;17(3):195–201. doi: 10.1097/00002341-200105000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]