Abstract

Molecular diagnostic assays offer both exquisite sensitivity and the ability to test a wide variety of sample types. Various types of environmental sample, such as detritus and concentrated water, might provide a useful adjunct to sentinels in routine zebrafish health monitoring. Similarly, antemortem sampling would be advantageous for expediting zebrafish quarantine, without euthanasia of valuable fish. We evaluated the detection of Mycobacterium chelonae, M. fortuitum, M. peregrinum, Pseudocapillaria tomentosa, and Pseudoloma neurophilia in zebrafish, detritus, pooled feces, and filter membranes after filtration of 1000-, 500-, and 150-mL water samples by real-time PCR analysis. Sensitivity varied according to sample type and pathogen, and environmental sampling was significantly more sensitive than zebrafish sampling for detecting Mycobacterium spp. but not for Pseudocapillaria neurophilia or Pseudoloma tomentosa. The results of these experiments provide strong evidence of the utility of multiple sample types for detecting pathogens according to each pathogen's life cycle and ecological niche within zebrafish systems. In a separate experiment, zebrafish subclinically infected with M. chelonae, M. marinum, Pleistophora hyphessobryconis, Pseudocapillaria tomentosa, or Pseudoloma neurophilia were pair-spawned and individually tested with subsets of embryos from each clutch that received no rinse, a fluidizing rinse, or were surface-disinfected with sodium hypochlorite. Frequently, one or both parents were subclinically infected with pathogen(s) that were not detected in any embryo subset. Therefore, negative results from embryo samples may not reflect the health status of the parent zebrafish.

Abbreviations: MU, University of Missouri

Both clinical and subclinical naturally occurring infections are well established to introduce potentially confounding variability that can lead to invalid or misinterpreted experiments in mammalian animal models.1 There is growing awareness within the research community that this same dynamic exists for zebrafish.6,8,18,21,37,45 Moreover, evidence is mounting that both genetic background39 and stress37 influence infection phenotypes in zebrafish, as has been established for rodent models.30 Therefore, as is the case for rodents and other mammalian model species, the exclusion of infectious agents from zebrafish colonies is a critical component of reducing confounding variability in biomedical research and is facilitated by the use of purpose-bred pathogen-free animals, approved vendor lists, pathogen exclusion lists, quarantine practices, disinfection, routine sentinel health monitoring, and environmental monitoring.

Sentinel zebrafish, as conventionally described,22,48 are analogous to rodent soiled-bedding sentinels, whose routine evaluation has historically been the cornerstone of health monitoring in rodent colonies—even though it has long been recognized that not all pathogens transmit easily to soiled-bedding sentinels.2,31,43,49 Consequently, recent experiments have demonstrated that a comprehensive approach incorporating both sentinel data and environmental sample types, such as cage swabs (cage level) and exhaust-air debris (cage, row, or rack level), provides a more complete representation of rodent population health.2 Pathogen transmission in zebrafish colonies more closely resembles the situation in conventionally housed rodent colonies than that of rodent colonies housed in ventilated racks or static microisolation cages, although ventilated rodent racks where sentinels receive exhaust air from the colony in addition to soiled bedding4 may be a better approximation of zebrafish sentinel exposure. In contrast to rodents, where cage-level biocontainment is relatively common,4,7,51 most zebrafish are housed in recirculating aquaculture systems, where water provides an effective medium for pathogen transmission.6,20,30 When zebrafish colonies are housed in recirculating systems, detritus accumulates in small amounts on the floor of individual tanks and in larger amounts in the sump, where the effluent water from the colony is collected for filtration prior to UV treatment. Tank or system detritus—sometimes referred to as sediment or sludge—is a mixture of feces, uneaten food, and other debris. A wide variety of bacteria, including mycobacteria and cyanobacteria, as well as fungi, algae, oomycetes, protozoa, and micro- and macroinvertebrates can inhabit detritus in zebrafish systems. Detritus, which has been used as a real-time PCR sample type for other aquatic species,10,47 is similarly a very attractive environmental sample for zebrafish health monitoring because it is easy to collect; can be obtained at the tank, rank, or system level; and includes fecal material along with a variety of microscopic particulates that are coated with biofilms.

In most recirculating systems designed to house zebrafish, water passes through tanks that are plumbed in parallel (to reduce between-tank horizontal pathogen transmission), and the effluent water from individual colony tanks is collected and supplies one or more tanks containing rack- or system-sentinel zebrafish. Recirculating systems typically include zebrafish of different genetic backgrounds and may include the colonies of multiple investigators. The potential consequences of unrecognized pathogens are increased for large recirculating systems that house large numbers of fish, colonies belonging to multiple principal investigators, and more genetically diverse fish. Immunologically robust fish populations, which may include wild-type zebrafish lines, or in some cases, other fish species such as Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes)23 may act as pathogen reservoirs, subclinically harboring and shedding pathogens that can cause disease in less robust or immunocompromised lines of fish housed on the same system.

Prior to the availability of PCR-based assays, zebrafish health monitoring primarily involved histopathology of whole adult zebrafish,5 such as intentionally placed sentinels, escapees (that is, sump fish), older fish, retired breeders, and moribund colony zebrafish. However, diagnostic real-time PCR analysis offers key advantages over histopathology, including exquisite sensitivity, identification of mycobacteria to the species level, and the ability to test ‘found dead’ zebrafish that exhibit postmortem autolysis. In addition, PCR analysis can be used to evaluate a wide variety of sample types, including biofilms, detritus (mixture of feces, uneaten food, and debris), embryos, feces, filter materials, live feeds, manufactured feeds, microbial cultures, sperm, surface swabs, and water. The ability to test environmental samples with increased sensitivity provides a useful adjunct to sentinel testing,6 as has been demonstrated for rodent colonies,2,7,17 and can assist in the identification of potential sources of contamination, the stage in a process where contamination occurs, and evaluation of the extent of contamination that has occurred.

As does zebrafish health monitoring, quarantine for zebrafish colonies presents unique challenges. Many institutions have adopted a fertilized ‘eggs-only’ policy,20 only allowing the entry of surface-disinfected embryos into main systems to reduce the introduction of new pathogens. Purpose-bred zebrafish are shipped typically as several breeding pairs or as a clutch of embryos. Genetically modified zebrafish that infrequently survive to adulthood or do not spawn well may be supplied as a few very valuable adults, for which antemortem tests would be advantageous. Moreover, chlorine toxicity to zebrafish embryos is greater at 24 h after fertilization than at 6 h afterward,19 such that embryo survival might be unacceptably low as a result of surface disinfection by the receiving institution at the time of arrival.

Accepting embryos that are surface-disinfected at another institution is risky for several reasons. Protocols vary, and the efficacy of surface disinfection with sodium hypochlorite (by far the most commonly used surface disinfectant for zebrafish embryos), is concentration-, contact time-, and pH-dependent.11 The spores of the most commonly detected pathogen of zebrafish, Pseudoloma neurophilia, can be transmitted vertically through the inclusion of infectious spores within unfertilized and fertilized zebrafish eggs41 and are resistant to surface disinfection with sodium hypochlorite.11 In addition, pathogens inside eggs are shielded from surface disinfection by the surrounding organic material, regardless of whether that particular embryo survives. In addition, mycobacteria are chlorine-resistant, especially when incorporated into biofilms, and clump together due to high cell-surface hydrophobicity.26,46

Many institutions therefore raise incoming embryos to adulthood during quarantine, to surface-disinfect the progeny inhouse. The parents can then be submitted for diagnostic evaluation while the second generation remains in quarantine. If pathogens are identified in either generation, the process often is repeated for another generation, with some lines remaining in quarantine for as long as 6 mo. Holding zebrafish in quarantine for months is problematic because of space constraints and because it can delay research or, in institutions that allow it, require research to be conducted in quarantine. Research in quarantine is a biosecurity risk and increases zebrafish manipulations and human traffic in the quarantine area, where multiple zebrafish lines, sources, and various pathogens may be present. Therefore more efficient ways to evaluate zebrafish held in quarantine are needed urgently.

Few antemortem diagnostic tests have historically been available for fish.20 PCR-based diagnostics have recently become available to the zebrafish community and allow the analysis of a wide variety of possible sample types. In addition, real-time PCR analysis can be used to detect Pseudoloma neurophilia in zebrafish eggs, sperm, and embryos in addition to filtered spawn-water samples.38 However, to our knowledge, the use of antemortem zebrafish sample types such as eggs and sperm for molecular analysis to detect other pathogens has not been evaluated. In the present study, we compared the utility of several antemortem and environmental sample types for pathogen detection by real-time PCR analysis. For valuable zebrafish lines received as breeding pairs, easy-to-collect antemortem samples include embryos and feces. For zebrafish received as embryos, a subset of received embryos might be tested as a diagnostic sample representing either the remaining embryos in the shipment or the parents (and by extension, the facility of origin). Because zebrafish supplied as embryos are often surface-disinfected with sodium hypochlorite, we further sought to compare surface-disinfected embryos with embryos that were not surface-disinfected, which either were untreated or underwent fluidized rinsing in disinfected fish water.

Materials and Methods

Environmental and fecal experiments.

Animals and husbandry.

Animals in the environmental and fecal experiments were housed in the AAALAC-accredited facility at IDEXX BioResearch (Columbia, MO) in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals,16 and all procedures were approved by the University of Missouri–Columbia Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol no. 7554). All zebrafish were housed in the same room in static or flow-through aquaria supplied with reverse-osmosis–purified water that was remineralized by using a commercially available product (Replenish, Seachem Laboratories, Madison, GA). These tanks were plumbed so that they could be operated as flow-through or static tanks. During the months leading up to the study, both tanks were set to flow-through, but they were both operated as static tanks during both trials. Two colonies of zebrafish (populations A and B), each enzootically infected with multiple zebrafish pathogens, were maintained on a 14:10-h light:dark cycle at approximately 0.7 fish per liter in separate but adjacent 75.7-L glass aquaria (Aqueon Products, Franklin, WI) on the same rack, with each aquarium containing approximately 50 adult, mixed-sex zebrafish. Fish were fed at least once daily with a combination of manufactured feeds (Golden Pearls, 5 to 50 μm, High-Protein Fry Green Granules, Kens Fish, Taunton MA) and dehydrated decapsulated brine shrimp cysts (Kens Fish, Taunton, MA) that were chemically decapsulated by using a concentrated chlorine solution and dehydrated as part of the manufacturing process. To aid in stable maintenance of water-quality parameters (Table 1), the aquaria were equipped with individual air-stone aeration and biologic filtration, including power filters (AquaClear 20 Power Filter, Rolf C Hagen, Mansfield, MA) containing plastic-foam filter material (AquaClear 20 Foam Filter Inserts, Rolf C. Hagen, Mansfield, MA), which with sponge filters (Aquarium Technology, Scottdale, GA) provided the substrate for biologic filtration.

Table 1.

| Environmental and fecal experimenta |

Embryo and surface-disinfection experimentb,c |

|||

| Parameter | Range | Testing frequency | Range | Testing frequency |

| pH | Stable at 7.2–7.8 | Weekly | Stable at 6.8–8.5 | Continuous |

| Temperature | Stable at 22–23 °C | Daily | Stable at 26–28 °C | Continuous |

| Total ammonia nitrogen | 0 ppm (mg/L) | Weekly | 0 ppm (mg/L) | Weekly |

| Nitrite | 0 ppm (mg/L) | Weekly | 0 ppm (mg/L) | Weekly |

| Nitrate | <40 ppm (mg/L) | Weekly | <10 ppm (mg/L) | Weekly |

| Alkalinity | Stable 40–80 ppm (mg/L) | Weekly | Stable at 40–80 ppm (mg/L) | Monthly |

| Hardness | Stable at ~150 ppm (mg/L) | Weekly | Stable at 100–150 ppm (mg/L) | Monthly |

| Conductivity | — | NM | Stable at ~1500 | Continuous |

| Dissolved oxygen | — | NMd | Stable at 7–8 ppm (mg/L) | Monthly |

| Carbon dioxide | — | NMd | Stable at 2–5 ppm (mg/L) | Monthly |

NM, not measured

Tanks were plumbed so that they could be operated as flow-through or static aquaria. The tanks were static for trials 1 and 2 and received a weekly water change of 20% of the tank volume.

Aquaneering and Aquarienbau Schwarz Commercial Recirculating Systems.

Recirculating systems received a daily water change of 10% of system volume.

Air-stone aeration provided.

The zebrafish in population A were line AB and Casper55 zebrafish obtained from enzootically infected zebrafish colonies. Five zebrafish pathogens—Mycobacterium chelonae, M. fortuitum, M. peregrinum, Pseudocapillaria tomentosa, and Pseudoloma neurophilia—were enzootically maintained continuously in the housing tank for more than 12 mo before this study, such that the prevalence of infections was high for trial 1, and any zebrafish that developed anorexia or became lethargic during this period were euthanized. During the 12 mo before the study, population A was determined to be free of Edwardsiella ictaluri, Flavobacterium columnare, Ichthyophthirius multifiliis, infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus, M. abscessus, M. haemophilum, M. marinum, Piscinoodinium pillulare, and Pleistophora hyphessobryconis, as determined by repeated evaluation with real-time PCR analysis and histopathology of euthanized fish.

The zebrafish in population B were retired broodstock of unknown genetic background obtained from a research population and were enzootically infected with 5 zebrafish pathogens—M. chelonae, M. fortuitum, M. haemophilum, M. peregrinum, and Pseudoloma neurophilia. The retired broodstock were cohoused for 4 mo prior to sample collection to maximize the prevalence of subclinical infections in population B for trial 1. During the 4 mo prior to the study, Population B was determined to be free of Edwardsiella ictaluri, Flavobacterium columnare, Ichthyophthirius multifiliis, infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus, M. abscessus, M. marinum, Piscinoodinium pillulare, Pleistophora hyphessobryconis, and Pseudocapillaria tomentosa as determined by repeated evaluation with real-time PCR and histopathology of euthanized fish.

Thus, the pathogens in each population were identical, except that population A was positive for Pseudocapillaria tomentosa but not M. haemophilum, whereas Population B was positive for M. haemophilum but not Pseudocapillaria tomentosa. The 2 colonies were maintained separately because the presence of both of these pathogens in the same population would likely result in increased morbidity and mortality. Zebrafish in both tanks were monitored daily for clinical signs, and the health status of each population was monitored by necropsy, real-time PCR analysis, and histopathologic evaluation of clinically diseased zebrafish. After sample collection for trial 1, both zebrafish populations were replenished to 50 animals by using adult, mixed-sex, wildtype AB zebrafish from a breeding population enzootically infected with Mycobacterium chelonae, M. fortuitum, and M. peregrinum but free of Edwardsiella ictaluri, Flavobacterium columnare, Ichthyophthirius multifiliis, infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus, M. abscessus, M. haemophilum, M. marinum, Piscinoodinium pillulare, Pleistophora hyphessobryconis, Pseudocapillaria tomentosa, and Pseudoloma neurophilia, as determined by multiple real-time PCR assays and histopathologic evaluation of euthanized fish from this population. Replenished populations A and B were cohoused for 4 wk to allow limited pathogen transmission, resulting in a lower prevalence of infections in trial 2.

Collection of environmental samples.

Environmental sample types included water samples concentrated by filtration and detritus collected from the tank floor. Water samples (1000, 500, or 150 mL) were collected from the middle of the water column by using a pipette and subsequently passed through a sterile 0.2-μm filter (Nalgene Sterile Analytical Filter Unit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) under vacuum. The filter membrane then was removed aseptically, placed in a sterile culture dish (Fisherbrand Petri Dish, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and cut into 2 equal halves by using a no. 22 sterile scalpel blade (Exel International, St. Petersburg, FL). One half was submitted as a sample for real-time PCR analysis, and the other was divided into 2 equal pieces, each equivalent to 1/4 of the complete filter membrane. One piece was submitted as a sample for real-time PCR analysis, and the other was discarded. Detritus samples were collected by aspirating sediment from the floor of the tank by using disposable polyethylene transfer pipettes (Fisherbrand Disposable Graduated Transfer Pipettes, Thermo Fisher Scientific) until a 2-mL volume of sample was obtained and placed in a 2 mL Safe-Lock microcentrifuge tube (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany).

Fecal collection and euthanasia.

For overnight fecal collection, 36 zebrafish were removed from each population at one time for each trial and divided into 6 groups, with each group of 6 zebrafish housed overnight in covered 3-L plastic static tanks equipped with a false floor made of black polypropylene mesh (Plastic Canvas, Darice, Strongsville, OH) and clean system water. The zebrafish were collected from the 3-L tanks the following morning and euthanized by hypothermal shock in accordance with the AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals.27 Euthanized zebrafish were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and bisected longitudinally; one-half of each fish was processed for real-time PCR analysis (described following), and the other half was stored at –80 °C. The feces were collected from the floor of the 3-L tanks by using disposable polyethylene transfer pipettes, with each pooled fecal sample representing the 6 zebrafish in a single 3-L tank. Once the zebrafish and feces were removed, any embryos present were collected and pooled as a single sample representing the group of 6 zebrafish. Zebrafish embryos were euthanized by hypothermal shock, and euthanasia was assured by a secondary chemical means as indicated in the AVMA Guidelines.27 Because sodium hypochlorite destroys template DNA and thus degrades the embryo samples for real-time PCR analysis, guanidine hydrochloride was used instead.

Molecular analysis.

For both trials, detritus, filter membranes, pooled embryos, pooled feces, and individual zebrafish from each population were submitted to IDEXX BioResearch (Columbia, MO), and tested by real-time PCR assays for 6 pathogens: M. chelonae, M. fortuitum, M. haemophilum, M. peregrinum, Pseudocapillaria tomentosa, and Pseudoloma neurophilia. All sample types were mechanically disrupted with a stainless steel ball-bearing in a guanidine-based lysis buffer by using a commercially available instrument (TissueLyser II, Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Total nucleic acids were extracted according to standard protocols for a commercially available platform (One-For-All Vet Kit, Qiagen). Fluorogenic real-time PCR assays were based on the IDEXX BioResearch proprietary service platform (IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, ME) and were performed at IDEXX BioResearch Laboratory. Assay primers and hydrolysis probes were designed by using commercially available software (version 3.0, PrimerExpress, Applied BioSystems, Foster City, CA). Real-time PCR analysis was performed with standard primer and probe concentrations (Applied Biosystems) by using a commercially available master mix (LightCycler 480 Probes Master, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) in a 384-well plate configuration in a commercially available instrument (LightCycler 480, Roche Applied Science). All IDEXX BioResearch real-time PCR assays have been validated to detect fewer than 10 template copies of target DNA. Positive and negative controls were run for all samples tested. A hydrolysis probe–based real-time PCR assay targeting a universal bacterial reference gene (16S rRNA) was amplified for all samples tested to determine the amount of genomic DNA present in the test sample, confirm DNA integrity, and verify the absence of PCR inhibition. For all zebrafish tissue and embryo samples, a eukaryotic reference gene (18S rRNA) was amplified as an additional control. Diagnostic real-time PCR analysis and amplification of the product for sequence analysis were performed by using standard primer and probe concentrations with a commercially available master mix (LightCycler 480 Probes Master, Roche) on a commercially available real-time PCR platform (LightCycler 480, Roche).

Embryo- and surface-disinfection experiments.

Animals and husbandry.

Zebrafish used in the embryo study were housed in the AAALAC-accredited facilities at Boston Children's Hospital (Boston, MA) and submitted to IDEXX BioResearch for euthanasia and necropsy. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Guide, and all procedures were approved by the Boston Children's Hospital Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol no. 14-09-2817). Zebrafish used for the embryo study were clinically normal tankmates of zebrafish exhibiting clinical signs (emaciation, scale edema, spinal curvature, open lesions) and were obtained from 2 zebrafish colonies at Boston Children's Hospital historically positive for multiple pathogens, including M. chelonae, M. fortuitum, M. haemophilum, M. marinum, Pleistophora hyphessobryconis, Pseudocapillaria tomentosa, and Pseudoloma neurophilia, as determined by semiannual evaluation of planned sentinels by histopathology and real-time PCR analysis as well as environmental samples by real-time PCR. Zebrafish were maintained and spawned at Boston Children's Hospital as previously described22,24,25 (Table 1). Zebrafish were maintained under a 14:10-h light:dark cycle. After spawning, embryo collection, and embryo treatments, zebrafish and embryos were shipped overnight to IDEXX BioResearch for euthanasia and analysis. Euthanasia was achieved by hypothermal shock in accordance with the AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals27 and the Guide16 and were approved by the University of Missouri–Columbia Animal Care and Use Committee. Embryo euthanasia was assured by a secondary chemical means after hypothermal shock as indicated in the AVMA Guidelines.27 Because sodium hypochlorite destroys template DNA and thus degrades the embryo samples for real-time PCR analysis, guanidine hydrochloride was used instead. In addition, the present experiment would be confounded given that surface disinfection of the embryos by using sodium hypochlorite was an experimental variable.

Embryo and surface disinfection study experimental design and embryo collection.

Clinically diseased zebrafish were identified during daily health inspection of 2 large zebrafish colonies at Boston Children's Hospital that historically have been enzootically infected with multiple pathogens. Because clinically diseased zebrafish rarely spawn well, clinically normal tankmates of the zebrafish exhibiting clinical signs were selected for inclusion in the present study. Clinically normal tank mates were likely to be subclinically infected or exposed to pathogens, given that they had been cohoused with clinically diseased fish that were likely to be shedding one or more pathogens. Pairs of tankmates of clinically diseased zebrafish were pair-spawned according to an established protocol;23 both the parents and the embryos of 26 crosses producing clutches of at least 60 embryos were included in the study.

Fluidized rinse and surface disinfection of embryos.

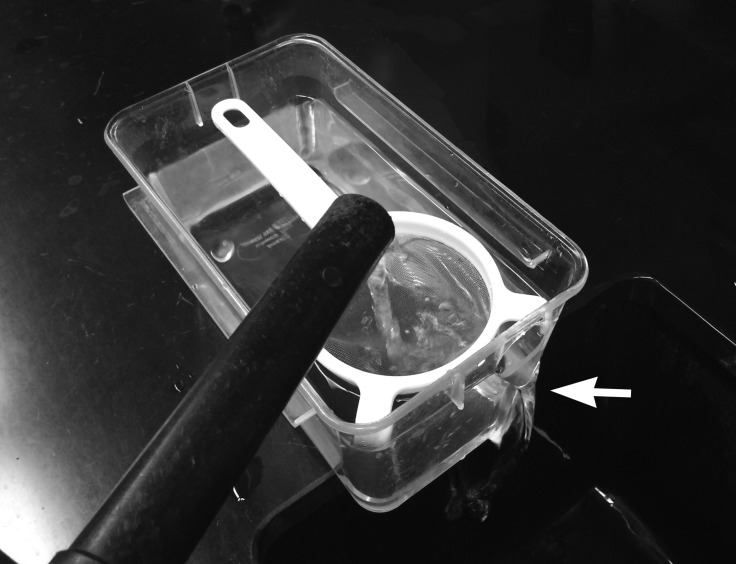

From each clutch of embryos, 3 samples of 20 embryos were collected; each sample received 1 of 3 treatments: surface disinfection with sodium hypochlorite, fluidized rinsing, or no rinse. Fluidized rinses were performed by using twice-UV–irradiated preconditioned fish water (disinfected fish water). The water is irradiated first after it passes through activated carbon and a reverse-osmosis filter and then again after it is pumped from a storage reservoir into pressurized lines that feed designated faucets in the room. For fluidized rinsing of zebrafish embryos, the flow rate was approximately 150 mL/min. The embryos were submerged and tumbling from turbulent flow in a tea strainer suspended in a 2-L polystyrene container that overflows into a sink (Figure 1). Surface-disinfected embryos were exposed to 33 ppm sodium hypochlorite in disinfected fish water for 5 min, transferred to a tea strainer, and submerged in 0.5% sodium thiosulfate solution for 2 min. The tea strainer containing the embryos was immediately transferred to a bath of disinfected fish water and subsequently fluidized with disinfected fish water for 30 s. Rinsed embryos were transferred to a tea strainer, submerged in a bath of disinfected fish water, and subsequently fluidized with disinfected fish water for 30 s.

Figure 1.

Fluidized rinsing of zebrafish embryos. Disinfected fish water passes through a tea strainer, which is suspended in a 2-L polystyrene container. The tea strainer holds zebrafish embryos, which remain submerged for 30 s and tumbling in the turbulent flow of disinfected fish water. An outflow drain (arrow) permits water to overflow into a sink.

Molecular analysis.

Individual pools of 20 unrinsed embryos, 20 fluidized embryos, 20 surface-disinfected embryos as well as both parent zebrafish from each cross were tested at IDEXX BioResearch by using real-time PCR assays for M. abscessus, M. chelonae, M. fortuitum, M. haemophilum, M. marinum, M. peregrinum, Pleistophora hyphessobryconis, Pseudocapillaria tomentosa, and Pseudoloma neurophilia. Real-time PCR analysis was performed as described for the environmental and fecal experiment.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were conducted by using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). For analysis of the environmental and fecal experiment, strong control of familywise error in the absence of an independence assumption for multiple comparisons was achieved by using the Bonferroni–Holm stepdown test in the MULTTEST procedure. To reduce the heteroscedasticity problem in multiple pairwise comparisons of proportions, we applied a variance-stabilizing double arcsine transformation (Freeman–Tukey test) before performing bootstrap-based multiplicity adjustment. The Fisher exact test was computed by using permutation-based adjustment. For linear trend analysis, we used the Cochran–Armitage test with permutation resampling. Multiple McNemar tests were handled by inputting and adjusting raw exact P values for multiplicity by stepdown Bonferroni–Holm method. Cohen κ agreement coefficients were calculated by using the FREQ procedure. For stratified sample design, we applied a jackknife method for variance estimation by using the SURVEYFREQ procedure. Tested differences for which the adjusted type I error was below 0.05 were claimed as statistically significant. For analysis of the embryo- and surface-disinfection experiment, the Exact McNemar test for paired proportions was used for analysis; significance was defined at the 0.05 level.

Results

Evaluation of environmental samples.

Table 2 presents the results of real-time PCR analysis for zebrafish, environmental samples, feces, and embryos by pathogen. Environmental samples consisted of either a 2-mL unconcentrated sample of detritus or a section of filter membrane through which 1000, 500, or 150 mL of tank water was filtered. Importantly, the diagnostic sensitivity of environmental sample types differed according to pathogen (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Real-time PCR test results (no. [% positive]) by pathogen for zebrafish and environmental samples collected from 2 populations

|

M. chelonae |

M. fortuitum |

|||||||||

| Population A |

Population B |

Total all trials | Population A |

Population B |

Total all trials | |||||

| Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | |||

| Individual zebrafisha | n = 36 | n = 36 | n = 36 | n = 36 | n = 144 | n = 36 | n = 36 | n = 36 | n = 36 | n = 144 |

| (post fecal collection) | 4 (11.1) | 2 (5.6) | 15 (41.7) | 6 (16.7) | 27 (18.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Environmental samples | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 24 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 24 |

| Detritus, 2 mL | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 24 (100) | 1 (16.7) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 19 (79.2) |

| 1/2 filter tested | ||||||||||

| 1000 mL water | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 24 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 24 (100) |

| 500 mL water | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 24 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 24 (100) |

| 150 mL water | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 24 (100) | 4 (66.7) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 22 (91.7) |

| 1/4 Filter Tested | ||||||||||

| 1000 mL water | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 24 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 24 (100) |

| 500 mL water | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 24 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 24 (100) |

| 150 mL water | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 24 (100) | 2 (33.3) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 20 (83.3) |

|

M. haemophilum |

M. peregrinum |

|||||||||

| Population A |

Population B |

Total all trials | Population A |

Population B |

Total all trials | |||||

| Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | |||

| Individual zebrafish | — | — | n = 36 | n = 36 | n = 72 | n = 36 | n = 36 | n = 36 | n = 36 | n = 144 |

| After fecal collection | NPb | NP | 24 (66.7) | 4 (11.1) | 28 (38.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) |

| Environmental samples | — | — | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 12 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 24 |

| Detritus, 2 mL | NP | NP | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 12 (100) | 2 (33.3) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 2 (33.3) | 14 (58) |

| 1/2 Filter tested | ||||||||||

| 1000 mL water | NP | NP | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 12 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 24 (100) |

| 500 mL water | NP | NP | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 12 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 24 (100) |

| 150 mL water | NP | NP | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 12 (100) | 4 (66.7) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 22 (91.7) |

| 1/4 Filter Tested | ||||||||||

| 1000 mL water | NP | NP | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 12 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 24 (100) |

| 500 mL water | NP | NP | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 12 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 24 (100) |

| 150 mL water | NP | NP | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 12 (100) | 3 (50.0) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 19 (79.2) |

|

P. tomentosa |

P. neurophilia |

|||||||||

| Population A |

Population B |

Total all trials | Population A |

Population B |

Total all trials | |||||

| Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | |||

| Individual zebrafish | n = 36 | n = 36 | n = 72 | n = 36 | n = 36 | n = 36 | n = 36 | n = 144 | ||

| After fecal collection | 32 (88.9) | 27 (75) | NP | NP | 59 (81.9) | 26 (72.2) | 4 (11.1) | 28 (77.8) | 8 (22.2) | 66 (45.8) |

| Environmental samples | n = 6 | n = 6 | — | — | n = 12 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 24 |

| Detritus, 2 mL | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | NP | NP | 12 (100) | 2 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 3 (12.5) |

| 1/2 Filter tested | ||||||||||

| 1000 mL water | 6 (100) | 2 (33.3) | NP | NP | 8 (66.7) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | 12 (50.0) |

| 500 mL water | 6 (100) | 1 (16.7) | NP | NP | 7 (58.3) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | 4 (66.7) | 0 (0) | 10 (41.7) |

| 150 mL water | 2 (33.3) | 0 (0) | NP | NP | 2 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (20.8) |

| 1/4 filter tested | ||||||||||

| 1000 mL water | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | NP | NP | 6 (50.0) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (25.0) |

| 500 mL water | 4 (66.7) | 1 (16.7) | NP | NP | 5 (41.7) | 5 (83.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (20.8) |

| 150 mL water | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NP | NP | 0 (0) | 4 (66.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (16.7) |

NP, pathogen not present; test results were uniformly negative (data not shown)

Zebrafish were sampled and tested individually.

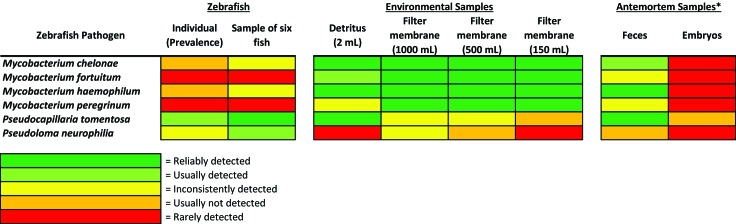

Figure 2.

Heat map summarizing the relative diagnostic sensitivity of the different environmental and antemortem real-time PCR sample types for the detection of each pathogen studied: dark green, reliably detected; light green, usually detected; yellow, inconsistently detected; orange, usually not detected; red, rarely detected; *embryos collected from a small subset of the population and used to represent the entire population.

Mycobacterium spp.

Environmental sample types (detritus and filtered water) detected 4 species of mycobacteria in each population more efficiently than testing zebrafish directly (Table 2). Prevalence (proportion of individually sampled zebrafish that tested positive) was determined after overnight fecal and embryo collection and varied between populations and between trials within each population. M. chelonae, M. fortuitum, and M. peregrinum were present in both populations for both trials, and M. haemophilum was present only in population B for both trials.

Testing environmental sample types was more sensitive than testing zebrafish for the detection of M. chelonae (P < 0.0001). Notably, 100% of 2-mL detritus samples (24 total) and 100% of filter-membrane samples (144 total) tested positive for M. chelonae across both populations, regardless of prevalence. In contrast, the number of zebrafish positive for M. chelonae varied widely, with 5.6% to 41.7% of sampled fish testing positive.

Similarly, testing environmental sample types was more sensitive than testing zebrafish for the detection of M. fortuitum (P < 0.0001). Although both populations historically have occasionally produced M. fortuitum-infected fish, M. fortuitum was not detected in any of the zebrafish samples tested in the current study, yet the organism was efficiently detected in environmental samples. The detection rate was 100% when either 500 or 1000 mL of water was passed through the filter membrane. Interestingly, M. fortuitum was detected in only 1 of 6 (16.7%) detritus samples in trial 1 of population A but in all 6 samples (100%) from all other trials. Therefore, filtering 1000 or 500 mL of water to provide a test sample was significantly more sensitive than testing detritus (P = 0.0235) from population A in trial 1, regardless of whether 1/2 or 1/4 of the filter membrane was tested. However, the detection of M. fortuitum did not differ between detritus and filtered water samples in the other trials. A trend toward reduced diagnostic sensitivity when only 150 mL of water was filtered in population A, trial 1 was not statistically significant.

M, haemophilum was present only in population B. Testing environmental sample types was more sensitive than testing zebrafish for the detection of M. haemophilum (P < 0.0001). The prevalence of M. haemophilum varied widely between the 2 trials, with 66.7% of sampled fish infected in trial 1 but only 11.1% infected in trial 2. However, as with M. chelonae, 100% of the 2-mL detritus samples (12 total) and 100% of filter membrane samples (72 total) yielded positive results.

M. peregrinum was detected in environmental samples from both zebrafish populations in all trials, but only one sampled zebrafish tested positive (population B, trial 1). Therefore, for the detection of M. peregrinum, testing environmental samples was always more sensitive than testing zebrafish (P < 0.0001). The detection of M. peregrinum in environmental samples was robust, but not all environmental samples tested positive. As with M. fortuitum, all filter-membrane samples representing 1000 or 500 mL of filtered water tested positive for M. peregrinum, as did 150-mL samples from 3 trials. For trial 1 of population A, a trend toward reduced diagnostic sensitivity when 150 mL of water was tested was nonsignificant.

Pseudocapillaria tomentosa.

The utility of environmental samples for detection of Pseudocapillaria tomentosa varied according to sample type. Pseudocapillaria tomentosa was present only in population A only, and prevalence was relatively high in both trials—88.9% in trial 1 and 75.0% in trial 2. All detritus samples tested positive for Pseudocapillaria tomentosa in both trials. For the detection of P. tomentosa, several sampling methods, including detritus, filtering 1000 mL of water and testing 1/2 of the filter membrane, and filtering 500 mL of water and testing 1/2 of the filter membrane, were significantly more sensitive (P < 0.05) than filtering 150 mL and testing 1/4 of the filter membrane.

Pseudoloma neurophilia.

As expected, the prevalence of Pseudoloma neurophilia infections was much higher for trial 1 than for trial 2 in both populations. Unconcentrated detritus samples were unreliable for detection of P. neurophilia regardless of whether prevalence was high or low. When P. neurophilia was highly prevalent (trial 1), a general trend toward greater diagnostic sensitivity when larger volumes of water were filtered was not significant.

All 6 environmental sampling methods were more sensitive than testing zebrafish when all pathogens were considered for both trials from both populations (P < 0.01). Similarly, environmental samples were more sensitive than testing zebrafish for all 4 mycobacterial species evaluated. However, environmental sample types were not significantly different than testing zebrafish for Pseudocapillaria tomentosa and Pseudoloma neurophilia (P = 0.1189). Among environmental sample types, overall diagnostic sensitivity was increased when 1000 mL of water was filtered and tested in population A, trial 1 (P = 0.0208).

Combining all pathogens together for population A in trial 1, 3 sampling methods were the most sensitive: 1000 mL (1/2 filter), 1000 mL (1/4 filter), and 500 mL (1/2 filter). These 3 sampling methods did not differ significantly from each other but were significantly more sensitive (P < 0.0001) than 4 remaining environmental sample types: 500 mL (1/4 filter), 150 mL (1/2 filter), 150 mL (1/4 filter), and detritus. In addition, 500 mL (1/4 filter) was intermediate in sensitivity and was more sensitive (P = 0.0017) than the 3 least sensitive sampling methods: 150 mL (1/2 filter), 150 mL (1/4 filter), and detritus.

Fecal experiment.

For each trial, 36 adult zebrafish were sampled from each population and divided into 6 groups of 6 fish each that were cohoused overnight for fecal and embryo collection (Table 3). One pooled fecal sample representing 6 zebrafish was obtained for each of 24 groups of 6 zebrafish, whereas each adult zebrafish was tested for each pathogen individually. Mycobacterium spp. and P. tomentosa were frequently detected in pooled fecal samples, whereas detection of P. neurophilia was inconsistent and detected only during trial 1 for population A. When 6 zebrafish were cohoused overnight for fecal collection, spawning occurred in some groups, but detection of pathogens in opportunistically collected pooled embryo samples was generally poor. In population A, none of the 6 groups produced embryos in trial 1, whereas 5 of the 6 groups produced embryos in trial 2. Only one of the 5 pooled embryo samples tested positive for P. tomentosa, but none of the 5 tested positive for any of the mycobacteria or P. neurophilia (Table 3). In population B, 2 of the 6 groups produced embryos in trial 1, whereas 4 of 6 groups produced embryos in trial 2. In trial 1, one of the 2 pools of embryos tested positive for both M. chelonae and M. peregrinum, but all other test results were negative. In trial 2, one of the 4 embryo samples tested positive for M. haemophilum only, and all other test results were negative.

Table 3.

Real-time PCR test results (no. [% positive]) by pathogen for feces and embryo clutches collected from 2 populations

|

M. chelonae |

M. fortuitum |

|||||||

| Population A |

Population B |

Population A |

Population B |

|||||

| Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | |

| Zebrafish | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 |

| Group 1a | 2 (33.3) | 0 | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Group 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Group 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Group 4 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (50) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Group 5 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Group 6 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Positive groups | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | 6 (100) | 4 (66.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Feces | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 |

| 3 (50) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 0 | 6 (100) | 1 (16.7) | 6 (100) | |

| Embryo clutches | — | n = 5 | n = 2 | n = 4 | — | n = 5 | n = 2 | n = 4 |

| — | 0 | 1 (50) | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

|

M. haemophilum |

M. peregrinum |

|||||||

| Population A |

Population B |

Population A |

Population B |

|||||

| Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | |

| Zebrafish | — | — | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 |

| Group 1 | NP | NP | 2 (33.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Group 2 | NP | NP | 4 (66.7) | 4 (66.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Group 3 | NP | NP | 6 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Group 4 | NP | NP | 4 (66.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Group 5 | NP | NP | 3 (50) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 |

| NP | NP | 5 (83.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Positive groups | — | — | 6 (100) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 |

| Feces | — | — | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 |

| NP | NP | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 0 | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Embryo clutches | — | — | n = 2 | n = 4 | n = 0 | n = 5 | n = 2 | n = 4 |

| NP | NP | 0 | 1 (25) | 0 | 0 | 1 (50) | 0 | |

|

P. tomentosa |

P. neurophilia |

|||||||

| Population A |

Population B |

Population A |

Population B |

|||||

| Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | |

| Zebrafish | n = 6 | n = 6 | — | — | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 |

| Group 1 | 5 (83.3) | 6 (100) | NP | NP | 5 (83.3) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| Group 2 | 4 (66.7) | 4 (66.7) | NP | NP | 3 (50) | 0 | 5 (83.3) | 3 (50) |

| Group 3 | 6 (100) | 5 (83.3) | NP | NP | 3 (50) | 0 | 4 (66.7) | 0 |

| Group 4 | 6 (100) | 4 (66.7) | NP | NP | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (66.7) | 1 (16.7) |

| Group 5 | 5 (83.3) | 4 (66.7) | NP | NP | 5 (83.3) | 0 | 6 (100) | 0 |

| Group 6 | 6 (100) | 4 (66.7) | NP | NP | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | 2 (33.3) |

| Positive Groups | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | — | — | 6 (100) | 3 (50) | 6 (100) | 4 (66.7) |

| Feces | n = 6 | n = 6 | — | — | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 |

| 6 (100) | 4 (66.7) | NP | NP | 4 (66.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Embryo clutches | — | n = 5 | — | — | — | n = 5 | n = 2 | n = 4 |

| — | 1 (20) | NP | NP | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

—, no embryos were produced; NP, pathogen not present in population—test results were uniformly negative (data not shown)

Groups 1–6 are subsets of the same individually sampled zebrafish in Table 2.

Embryo- and surface-disinfection experiment.

A total of 26 pair-crosses, each comprising 2 parents and 3 pools of 20 embryos (5 samples per cross), were analyzed. Pools of 20 embryos—whether unrinsed, fluidized, or surface-disinfected—proved insensitive as a diagnostic sample for all pathogens tested (Table 4). Only 2 zebrafish in this experiment were infected with Mycobacterium spp.: one male for M. chelonae, and one male for M. marinum; neither was detected in the embryos. At least one parent in 9 of 26 crosses was infected with Pleistophora hyphessobryconis, but the organism was detected in the embryos in a single untreated embryo sample only. Similarly, at least one parent was infected with Pseudocapillaria tomentosa in 12 of 26 crosses, but the organism was detected in a single untreated embryo sample only. Finally, 13 of 26 crosses included at least one parent infected with Pseudoloma neurophilia, but only one untreated embryo sample tested positive.

Table 4.

Results (no. [% positive]) from real-time PCR analysis of male zebrafish, female zebrafish, and 3 subsets of embryos from 26 pair-crosses

| M. chelonae | M. marinum | P. hyphessobryconis | P. tomentosa | P. neurophilia | M. chelonae | |

| Male zebrafish (n = 26) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (3.8) | 3 (11.5) | 11 (42.3) | 12 (46.2) | 1 (3.8) |

| Female zebrafish (n = 26) | 0 | 0 | 6 (23.1) | 6 (23.1) | 10 (38.5) | 0 |

| Male only : female only : both sexes | 1 : 0 : 0 | 1 : 0 : 0 | 3 : 3 : 0 | 6 : 1 : 5 | 3 : 1 : 9 | 1 : 0 : 0 |

| Unrinsed embryos (n = 26) | 3 (11.5) | 0 | 1 (3.8) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (3.8) | 3 (11.5) |

| Fluidized (rinsed) embryos (n = 26) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Surface-disinfected embryos (n = 26) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

All samples tested negative for M. abscessus, M. fortuitum, M. haemophilum, and M. peregrinum.

Discussion

Detection of different rodent pathogens is accomplished most efficiently by testing the optimal sample type (blood, cage swab, feces, fur swab,) according to the life cycle of each pathogen. Concentration of water by filtration for PCR detection of pathogens is fundamentally similar to sampling rodent exhaust-air plenum filters, which concentrate airborne particulates expelled in exhaust air from rodent populations. The ability to detect rodent pathogens by plenum sampling varies by agent.2 Similarly, some rodent pathogens transmit easily to soiled-bedding sentinels whereas others, such as fur mites and respiratory bacteria, transmit poorly or not at all.13,15,28,43,51 Most rodent health monitoring programs therefore rely on multiple methods, including real-time PCR analysis of multiple sample types, to obtain a more complete view of colony health. The results of the current study support the efficacy of this strategy for routine zebrafish colony health monitoring.

Few publications have addressed the utility of environmental monitoring for zebrafish. One group cultured Mycobacterium spp. and amplified mycobacterial hsp65 gene sequences through conventional PCR analysis of biofilm swabs, subsequently identifying the mycobacteria to the species level by sequence analysis.53 However, sequence analysis is problematic for routine diagnostic evaluation of complex samples. Other authors demonstrated the utility of real-time PCR assays to detect Pseudoloma neurophilia in multiple sample types, including 1-L water samples concentrated by filtration followed by extraction of template DNA from the filter membrane.38 Concentration by filtration allows a large volume of water to be tested as a single sample, although the collection and filtration of volumes of water is labor-intensive and may not be practical for routine sampling in large facilities. The zebrafish populations in the present study were housed in static aquaria, which are the simplest type of experimental system. Recirculating and flow-through systems are similar in many respects to static aquaria but involve additional variables including flow rate, turbulence, surface area available for biofilm formation in pipes and tubing, efficacy of UV treatment, frequency of tank change, and proportion of water recirculated (recirculating systems only). Because most zebrafish in biomedical research are housed in recirculating systems, additional experiments are needed to help elucidate the effect of these variables on environmental monitoring programs for zebrafish facilities. In recirculating systems for zebrafish, effluent from all tanks on the system typically is collected into a sump. The sump thus provides a convenient sampling location that is similar to sampling from a large individual tank, given that it receives effluent from the entire population housed on the system.

Importantly, detection of 4 species of mycobacteria in environmental samples including detritus and filtered water by real-time PCR was robust even when relatively few fish were infected. This pattern reflects the dual lifestyle of the Mycobacterium spp. known to infect zebrafish, all of which are facultative pathogens.12,53 Facultative pathogens proliferate in the environment, form biofilms, and occasionally infect a new host, which may be either immunocompetent or immunocompromised. Therefore, the utility of environmental sample types for detecting other Mycobacterium species, for example, M. abscessus, M. marinum, and M. saopaulense,35 is likely to be very similar.

M. chelonae was detected in every environmental sample from both populations in both trials (168 samples), indicating that this species is common in the zebrafish environment. Similarly, M. haemophilum was detected in every environmental sample from population B (84 samples). M. fortuitum and M. peregrinum were detected in 157 of 168 (93.5%) and 151 of 168 (89.9%) environmental samples, respectively. It is likely that some species are more common in the environment of a zebrafish system than others, although very little is known about the ecological interactions among mycobacterial species in zebrafish systems. However, evidence from other contexts, such as mycobacterial contamination of municipal water supply lines, suggests that when multiple Mycobacterium spp. are present, the species may occupy somewhat different niches, thus limiting direct competition among mycobacterial species within a system.9

The differences in prevalence of M. chelonae and M. haemophilum between trials in population B may reflect the longer exposure time of the original population compared with the restocked zebrafish, which were exposed for only 1 mo. Most mycobacterial infections are chronic infections that fish acquire over a period of months, and infected zebrafish may subsequently remain subclinical for some time. Interestingly, only one zebrafish in this experiment was infected with M. peregrinum, and none were infected with M. fortuitum, despite the environmental presence of these species in both populations during the study and the detection of zebrafish infected with these pathogens prior to this study. One possibility is that M. fortuitum and M. peregrinum are less infectious to immunocompetent zebrafish than are M. chelonae and M. haemophilum, but experimental infection studies with known exposures are needed to make that determination. In addition, multiple strains of a single mycobacterial species, such as M. chelonae or M. haemophilum, might be present within a population, and some strains might be more common in biofilms (and thus more easily detected by environmental samples) or more infectious to zebrafish than other strains. One group cultured and typed strains of M. chelonae in infected fish and biofilms in one facility and found that, of 3 M. chelonae strains infecting zebrafish, 2 were isolated from biofilms also.54 Moreover, the strain that most commonly caused infections in the zebrafish was also the one isolated from biofilms most often.54 Therefore, multiple strains of M. chelonae infect zebrafish, and the same strains can be detected in biofilms. Notably in the cited study, no strains were isolated from biofilms that were not also found to infect zebrafish.54 Regardless, detection of organisms in any of these sample types reveals that the pathogen has not been excluded from the system and that the fish housed on that system have potentially been exposed to that agent. Colony health monitoring for research animals, both mammalian and nonmammalian species, is based on the exclusion and routine surveillance of opportunists or pathogens identified at the species level. The adverse impact of individual mycobacterial species on colony health varies according to the mycobacterial species, zebrafish phenotype, and the type of research. Therefore, as with rodents, management decisions regarding zebrafish should be based on these considerations, which may result in different health statuses for different systems within the same facility or institution.

In contrast to mycobacteria, the parasites Pleistophora hyphessobryconis, Pseudoloma neurophilia, and Pseudocapillaria tomentosa are all obligate pathogens that can only reproduce in a suitable host and are then shed as environmentally persistent spores or eggs. Pseudoloma neurophilia is an endoparasitic microsporidium that infects a wide array of zebrafish tissues, and infection often persists in the CNS and ova40 and resulting in the accumulation of large numbers of infectious spores in these tissues. Spores primarily are shed during spawning or due to cannibalism50 but may be shed in smaller numbers in feces and urine.42 Pseudocapillaria tomentosa is an endoparasitic nematode that sheds unembryonated eggs in the feces, which embryonate in the environment and become infectious.6 For obligate parasites, the level of shedding directly affects the levels of organisms present in the environment. In contrast, for facultative pathogens, environmental levels also reflect the proliferation that occurs in the environment.

In the current study, detection of the obligate pathogens Pseudocapillaria tomentosa and Pseudoloma neurophilia in environmental samples was less consistent than for the mycobacterial species. For both pathogens, detection using filter membranes was very poor unless the prevalence in the population was high, and then detection improved with the volume of filtered water. In trial 1, with very high prevalence (88.9%), the detection of Pseudocapillaria tomentosa in filtered water was 100% only when 1000 mL of water passed through the filter membrane but was good (66.7% to 100%) when 500 mL of water was passed through the filter membrane. In trial 2 (lower prevalence), the prevalence was still quite high (75%), but the detection of Pseudocapillaria tomentosa from filtered water was poor, with 0% to 33% of samples testing positive. The difference in prevalence probably contributed to poor detection in trial 2, but it is also important to note that the zebrafish in trial 1 had a longer window of exposure, and most infections were mature and shedding Pseudocapillaria tomentosa eggs at the beginning of the experiment. In contrast, the majority of the zebrafish in trial 2 had been exposed for only 4 wk and therefore might not yet have been shedding eggs back into the system, both because the timing of infections is unknown for individual zebrafish and because the exact prepatent period for Pseudocapillaria tomentosa is unknown (but is less than 2 mo).29 Whereas detection of Pseudoloma neurophilia in detritus was poor, detritus was a very effective sample type for detecting Pseudocapillaria tomentosa. All detritus samples tested positive for Pseudocapillaria tomentosa in both trials, likely reflecting the detection of eggs shed in zebrafish feces and indicating that detritus is an excellent environmental sample type for detection of Pseudocapillaria tomentosa.

For Pseudoloma neurophilia, detection in filtered water was very good only when the infection was highly prevalent (trial 1) and 1000 mL of water was passed through the filter membrane. It should be noted that although the prevalence of infection was in some cases quite high in this experiment, the fish were housed at a much lower stocking densities than zebrafish are housed in a typical recirculating aquaculture system. It is therefore likely that the probability of detection under low-prevalence conditions might increase at higher stocking densities. The detection of Pseudoloma neurophilia spores in unconcentrated detritus samples was consistently very poor in all trials, with only 0% to 33.3% of detritus samples testing positive. The poor detection of Pseudoloma neurophilia in detritus samples, compared with the excellent detection of Pseudocapillaria tomentosa in detritus samples, likely reflects the infrequent shedding of Pseudoloma neurophilia compared with the relatively frequent shedding of dense Pseudocapillaria tomentosa eggs that settle in the detritus. P. tomentosa eggs may be denser than Pseudoloma neurophilia spores and therefore less likely to remain suspended in the water column.

In summary, both filter membranes and 2-mL samples of detritus were excellent diagnostic samples for Mycobacterium spp., especially when at least 500 mL of water was filtered. However, the detection of Pseudoloma neurophilia in environmental samples was more challenging: filter membranes were an effective sample type when the prevalence of infection was high and 1000 mL of water was filtered. It seems prudent, therefore, not to rely on environmental samples for detecting Pseudoloma neurophilia in routine monitoring but to include the evaluation of fish that have an increased likelihood of being infected, such as sentinels, fish found dead, fish showing clinical signs, and the oldest fish in a population. Finally, the detection of Pseudocapillaria tomentosa by using filter membranes was comparable to that of Pseudoloma neurophilia, but detection in detritus samples was much better, with 12 of 12 (100%) detritus samples testing positive.

The results of the environmental experiment have important implications for routine monitoring of zebrafish colonies. The most powerful tool for colony health management is the exclusion of pathogens from a system. Although all zebrafish colonies likely are enzootically infected with at least one mycobacterial species, the prevalence of mycobacterial infections in well-managed zebrafish colonies is often low, such that mycobacterial species can be easily missed if the sampled zebrafish are too few or too young. In contrast, all mycobacterial species in this study were reliably detected in environmental samples. Environmental samples provide a cost-effective and sensitive means for detecting mycobacteria and are thus an efficient adjunct to sentinel health monitoring.

In the fecal experiment, pooled fecal samples were obtained from 24 groups of 6 zebrafish each. Whether each zebrafish in the group contributed to the pooled fecal sample is unknown. Mycobacterial detection in feces was generally good and displayed some similarity to that from environmental sample types. Each pooled fecal sample may include 1) mycobacteria shed in the feces of an infected zebrafish, 2) ‘pass-through’ mycobacteria that were consumed in the home tank prior to collection, and 3) environmental mycobacteria that were transferred into the clean tank along with the zebrafish and that subsequently adhered to feces or were aspirated with feces during collection. Zebrafish regularly consume mycobacteria by grazing on tank detritus14,53 and feeding on protozoa,36 and, as shown for other fishes, macroinvertebrates.3,34,44 The gastrointestinal tract is the primary route of infection for zebrafish mycobacteriosis;14 however, the minimum infectious dose of each mycobacterial species for infecting immunocompetent zebrafish has not been established. Live and dead mycobacteria that pass through the gastrointestinal tract may be present in the feces at a detectable level but be below the level of live mycobacteria required to produce an infection, as is likely for feces testing positive for M. fortuitum or M. peregrinum. Feces can test positive but the zebrafish itself might test negative, both because the intestine is now emptied and because of the dilution effect associated with the template DNA, given that gut contents comprise a small proportion of the DNA extracted from zebrafish. In addition, small numbers of mycobacteria are transferred when netting and moving zebrafish because these organisms can exist in the environment in very high numbers relative to parasites. Combining the data for the 4 species-specific assays, 60% of group samples tested positive for at least one mycobacterial species when no fish were infected, increasing to 90% when one of the 6 fish was infected, and 100% of samples tested positive when 2 or more of the 6 fish were infected.

Pseudoloma neurophilia was not reliably detected in either feces or embryos in this experiment. Among the 19 groups in which at least one fish was infected with Pseudoloma neurophilia, only 4 (21%) fecal samples tested positive. Relatively poor detection in feces was not surprising for this agent, given that whereas P. neurophilia has the potential to be shed during spawning, in feces, and in urine;42 in many infected zebrafish, the microsporidia might be trapped in tissues such as hindbrain, spinal cord, and skeletal muscle and are released into the environment only once the zebrafish dies. It is also plausible that Pseudoloma neurophilia-infected zebrafish were less likely than uninfected tankmates to produce feces overnight. A reduction in appetite during chronic Pseudoloma neurophilia infections may contribute to decreased growth37 and the wasting syndrome associated with this parasite in zebrafish, which is historically known as ‘skinny disease.’32,33,52 It should also be noted that 23 of the 26 (88%) of the Pseudoloma neurophilia-infected zebrafish from population A were infected concurrently with Pseudocapillaria tomentosa, another parasite that is also associated with reduced appetite in infected zebrafish. In contrast, detection of Pseudocapillaria tomentosa in feces was much higher, reflecting the presence of eggs shed in the feces. When at least one of the 6 zebrafish was infected with Pseudocapillaria tomentosa, the infection was detected in 10 of the 12 (83%) fecal samples. Both cases in which feces tested negative were from trial 2 (lower prevalence), and infected zebrafish might have had early infections that were not yet shedding Pseudocapillaria tomentosa eggs in the feces.

Several groups of 6 zebrafish spawned overnight while feces were being collected. Once the feces were removed, the embryos from each group of 6 zebrafish were opportunistically collected as a clutch, and each clutch was pooled as a single sample for real-time PCR analysis. Pseudoloma neurophilia was not detected in pooled embryo samples in this experiment. Other colleagues previously demonstrated that Pseudoloma neurophilia could be detected by real-time PCR assay in 1-L samples of group-spawn water that were concentrated by filtration.38 Therefore, Pseudoloma spores might have been detected if the water in which the fish spawned had been tested. The quantity of embryos collected was small, suggesting that most fish did not spawn. Many factors are likely to influence whether fish spawn; however, when fish are known to be infected with multiple pathogens, it is intuitive that the healthiest zebrafish in each group would be most likely to participate in spawning. If true, this situation may help to explain the poor detection of Pseudoloma neurophilia and the poor overall pathogen detection from pooled embryo samples.

Several aspects of our current experiments can inform zebrafish quarantine practices. First, when adult zebrafish are received into quarantine, feces can reliably be collected overnight from groups of 6 adults to provide a useful antemortem PCR sample. Detection of mycobacteria and Pseudocapillaria tomentosa in feces is more likely than is the detection of Pseudoloma neurophilia in the same sample. Because Pseudoloma neurophilia is an extremely prevalent parasite in established zebrafish facilities, many facilities will be unable to completely exclude this organism from large (often centralized) recirculating systems that already support enzootically infected colonies. The data from this experiment suggest that collecting feces from fish during quarantine would provide an antemortem test for Mycobacterium spp. and Pseudocapillaria tomentosa. One potential concern described earlier is that zebrafish might not always produce feces overnight; however, this risk can be easily offset by pooling fecal samples collected at different time points, separated by days or weeks. It also seems prudent to pool feces collected from the same fish at different time points to increase the likelihood of detection.

The risk that the healthiest zebrafish in any group would be most likely to participate in spawning illustrates an important possible bias toward nondetection of pathogens that could easily occur in a quarantine setting if a small group of quarantined zebrafish were spawned and the embryos were submitted as an antemortem sample representing that small group of adult fish. However, these data do not discount the utility of a partial clutch as a diagnostic sample used to represent the entire clutch, to release the remainder of the clutch as appropriate. Caution is warranted; if a sample of embryos tested by PCR assay are used to represent the remainder of the clutch, the level of confidence that the remaining portion of the clutch is also negative is a function of the proportion of embryos sampled. There is always a chance that the remainder of the clutch contains a pathogen that was not present in the sampled portion.

Embryos can be sampled to represent a clutch of embryos, the parents, or the population from which they originated. Using a sample of embryos to represent the remainder of the clutch is reasonable, and the percentage of embryos sampled determines the likelihood of detecting a pathogen that is present. However, the results of the embryo- and surface-disinfection experiment suggest that the transmission of some pathogens by means of embryos may be relatively uncommon and that a sample comprising only a few embryos is a poor sample type for evaluating the health status of the parents or population of origin (Figure 2). If the embryos test positive, the results are significant. However, the negative predictive value is very low—yielding no confidence in a negative test result (Table 4). This conclusion is corroborated by the opportunistic sampling of embryo clutches in the fecal experiment described earlier.

Although more experimental data are needed to make this determination, the trend in the limited data that were collected (Table 4) suggests that fluidized rinsing of embryos may be a simple and effective means of reducing the number of pathogens that are carried with embryos, without exposing embryos to sodium hypochlorite. It is important to note that this method will not prevent the introduction of pathogens within an embryo, as has been demonstrated for Pseudoloma neurophilia.41

In conclusion, our current experiments provide strong evidence for the utility of multiple sample types to detect various pathogens depending on each pathogen's life cycle and ecological niche within zebrafish systems. Figure 2 includes a color-coded illustration that summarizes general conclusions based on the performance of various sample types in this set of experiments for detection of multiple infectious agents in zebrafish colonies. Environmental sample types, such as water concentrated by filtration and detritus, provided excellent detection of Mycobacterium spp., whereas testing fish compared with environmental samples did not differ significantly for the detection of Pseudoloma neurophilia. Pseudocapillaria tomentosa was easily detected in detritus and fecal samples as well as sampled fish, and feces are a better antemortem sample type than embryos for the detection of multiple pathogens. Additional experiments are needed to better understand the factors that influence the environmental persistence and proliferation of potential pathogens in zebrafish systems, to further refine sample collection for zebrafish health monitoring, and to optimize the incorporation of available diagnostic platforms to improve overall health-monitoring programs for zebrafish colonies.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Shannon Primm and Lisa M. Zell for their technical assistance. This work was partially funded by IDEXX BioResearch,; 4 of the 6 authors (MJC, RSL, AR, and LKR) are employed by IDEXX Laboratories.

References

- 1.Baker DG. 1998. Natural pathogens of laboratory mice, rats, and rabbits and their effects on research. Clin Microbiol Rev 11:231–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer BA, Besch-Williford C, Livingston RS, Crim MJ, Riley LK, Myles MH. 2016. Evaluation of rack design and disease prevalence on detection of rodent pathogens in exhaust debris samples from individually ventilated caging systems. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 55:782–788. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beran V, Matlova L, Dvorska L, Svastova P, Pavlik I. 2006. Distribution of mycobacteria in clinically healthy ornamental fish and their aquarium environment. J Fish Dis 29:383–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brielmeier M, Mahabir E, Needham JR, Lengger C, Wilhelm P, Schmidt J. 2006. Microbiologic monitoring of laboratory mice and biocontainment in individually ventilated cages: a field study. Lab Anim 40:247–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chow FW, Xue L, Kent ML. 2016. Retrospective study of the prevalence of Pseudoloma neurophilia shows male sex bias in zebrafish Danio rerio (Hamilton–Buchanan). J Fish Dis 39:367–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collymore C, Crim MJ, Lieggi C. 2016. Recommendations for health monitoring and reporting for zebrafish research facilities. Zebrafish 13 Suppl 1:S138–S148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Compton SR, Homberger FR, Paturzo FX, Clark JM. 2004. Efficacy of 3 microbiologic monitoring methods in a ventilated cage rack. Comp Med 54:382–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crim MJ, Riley LK. 2012. Viral diseases in zebrafish: what is known and unknown. ILAR J 53:135–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falkinham JO, 3rd, Norton CD, LeChevallier MW. 2001. Factors influencing numbers of Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and other mycobacteria in drinking water distribution systems. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:1225–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldman SH, Ramirez MP. 2014. Molecular phylogeny of Pseudocapillaroides xenopi (Moravec et Cosgrov 1982) and development of a quantitative PCR assay for its detection in aquarium sediment. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 53:668–674. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson JA, Watral V, Schwindt AR, Kent ML. 2007. Spores of 2 fish microsporidia (Pseudoloma neurophilia and Glugea anomala) are highly resistant to chlorine. Dis Aquat Organ 76:205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gauthier DT. 2015. Bacterial zoonoses of fishes: a review and appraisal of evidence for linkages between fish and human infections. Vet J 203:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grove KA, Smith PC, Booth CJ, Compton SR. 2012. Age-associated variability in susceptibility of Swiss Webster mice to MPV and other excluded murine pathogens. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 51:789–796. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harriff MJ, Bermudez LE, Kent ML. 2007. Experimental exposure of zebrafish, Danio rerio (Hamilton), to Mycobacterium marinum and Mycobacterium peregrinum reveals the gastrointestinal tract as the primary route of infection: a potential model for environmental mycobacterial infection. J Fish Dis 30:587–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodzic E, McKisic M, Feng S, Barthold SW. 2001. Evaluation of diagnostic methods for Helicobacter bilis infection in laboratory mice. Comp Med 51:406–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed. Washington (DC): National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen ES, Allen KP, Henderson KS, Szabo A, Thulin JD. 2013. PCR testing of a ventilated caging system to detect murine fur mites. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 52:28–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kent ML, Bishop-Stewart JK, Matthews JL, Spitsbergen JM. 2002. Pseudocapillaria tomentosa, a nematode pathogen, and associated neoplasms of zebrafish (Danio rerio) kept in research colonies. Comp Med 52:354–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kent ML, Buchner C, Barton C, Tanguay RL. 2014. Toxicity of chlorine to zebrafish embryos. Dis Aquat Organ 107:235–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kent ML, Feist SW, Harper C, Hoogstraten-Miller S, Law JM, Sanchez-Morgado JM, Tanguay RL, Sanders GE, Spitsbergen JM, Whipps CM. 2009. Recommendations for control of pathogens and infectious diseases in fish research facilities. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 149:240–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kent ML, Harper C, Wolf JC. 2012. Documented and potential research impacts of subclinical diseases in zebrafish. ILAR J 53:126–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawrence C. 2011. Advances in zebrafish husbandry and management. Methods Cell Biol 104:429–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawrence C, Adatto I, Best J, James A, Maloney K. 2012. Generation time of zebrafish (Danio rerio) and medakas (Oryzias latipes) housed in the same aquaculture facility. Lab Anim (NY) 41: 158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawrence C, Best J, James A, Maloney K. 2012. The effects of feeding frequency on growth and reproduction in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquaculture 368–369:103–108. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawrence C, James A, Mobley S. 2015. Successful replacement of Artemia salina nauplii with Marine Rotifers (Brachionus plicatilis) in the diet of preadult zebrafish (Danio rerio). Zebrafish 12:366–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Dantec C, Duguet JP, Montiel A, Dumoutier N, Dubrou S, Vincent V. 2002. Chlorine disinfection of atypical mycobacteria isolated from a water distribution system. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:1025–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Underwood W, Anthony R, Cartner S, Corey D, Grandin T, Greenacre CB, Gwaltney-Bran S, McCrackin MA, Meyer R, Miller D, Shearer J, Yanong R. 2013. AVMA guidelines for the euthanasia of animals: 2013 ed. Schaumburg (IL): American Veterinary Medical Association. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindstrom KE, Carbone LG, Kellar DE, Mayorga MS, Wilkerson JD. 2011. Soiled bedding sentinels for the detection of fur mites in mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 50:54–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lomakin VV, Trofimenko VY. 1982. [Capillariids (Nematoda: Capillariidae) of freshwater fish fauna of the USSR.] Trudy Gel'mintologicheskaia laboratorii 31:60–87. [Article in Russian]. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mansfield KG, Riley LK, Kent ML. 2010. Workshop summary: detection, impact, and control of specific pathogens in animal resource facilities. ILAR J 51:171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matthaei KI, Berry JR, France MP, Yeo C, Garcia-Aragon J, Russell PJ. 1998. Use of polymerase chain reaction to diagnose a natural outbreak of mouse hepatitis virus infection in nude mice. Lab Anim Sci 48:137–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matthews JL, Brown AM, Larison K, Bishop-Stewart JK, Rogers P, Kent ML. 2001. Pseudoloma neurophilia n. g., n. sp., a new microsporidium from the central nervous system of the zebrafish (Danio rerio). J Eukaryot Microbiol 48:227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray KN, Dreska M, Nasiadka A, Rinne M, Matthews JL, Carmichael C, Bauer J, Varga ZM, Westerfield M. 2011. Transmission, diagnosis, and recommendations for control of Pseudoloma neurophilia infections in laboratory zebrafish (Danio rerio) facilities. Comp Med 61:322–329. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nenoff P, Uhlemann R. 2006. Mycobacteriosis in mangrove killifish (Rivulus magdalenae) caused by living fish food (Tubifex tubifex) infected with Mycobacterium marinum. Dtsch Tierarztl Wochenschr 113:230–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nogueira CL, Whipps CM, Matsumoto CK, Chimara E, Droz S, Tortoli E, de Freitas D, Cnockaert M, Palomino JC, Martin A, Vandamme P, Leao SC. 2015. Description of Mycobacterium saopaulense sp. nov., a rapidly growing mycobacterium closely related with members of the Mycobacterium chelonae-Mycobacterium abscessus group. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 65:4403–4409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peterson TS, Ferguson JA, Watral VG, Mutoji KN, Ennis DG, Kent ML. 2013. Paramecium caudatum enhances transmission and infectivity of Mycobacterium marinum and Mycobacterium chelonae in zebrafish Danio rerio. Dis Aquat Organ 106:229–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]