Abstract

BACKGROUND

Prior studies suggested that most patients with early stage breast cancer (BC) were willing, for modest survival benefits, to receive 6 months of adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil, an older regimen that is infrequently used today. We examined preferences regarding the survival benefit needed to justify 6 months of a contemporary chemotherapy regimen.

METHODS

E5103 was a phase III trial which randomized BC patients to receive standard adjuvant doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide and paclitaxel with either bevacizumab or placebo. Serial surveys to assess quality of life were administered to patients enrolled between 01/01/2010 and 06/08/2010. Survival benefit needed to justify 6 months of chemotherapy by patients was collected at the 18 month assessment. A parallel survey was sent to physicians who had enrolled patients on the study.

RESULTS

Of 519 patients who had not withdrawn at a timepoint prior to 18 months, 87.8% responded to this survey. 175 (16%) physicians participated. We found considerable variation in patients’ preferences particularly for modest survival benefits: for 2 months of benefit, 57% would consider 6 months of chemotherapy, whereas 96% of patients would consider 6 months of chemotherapy for 24 months. Race and education were associated with choices. Physicians who responded were less likely to accept chemotherapy for modest benefit.

CONCLUSIONS

Among patients who received contemporary adjuvant chemotherapy in a randomized controlled trial, we found substantial variation in preferences regarding benefit worth undergoing chemotherapy. Differences between patients’ and physicians’ choices were also apparent. Eliciting preferences regarding risks and benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy is critical.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, drug therapy, patients, physicians, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Over the last 20 years, treatment paradigms for stage 1–3 breast cancer have evolved, and among many other advances, the use of adjuvant chemotherapy has become a routine consideration.1,2 Nevertheless, treatment decisions in the adjuvant setting can be particularly complex and benefits and risks of therapy can vary dramatically between different individuals given individual disease and therapy risks. For example, adjuvant chemotherapy reduces the risk of breast cancer recurrence for patients with stage 1–3 breast cancer by an average of 30%. For a patient less than 50 years of age with node positive disease, this yields at least a 10% absolute survival benefit and disease free survival gain of almost 1 year.2,3 In contrast, for a 50–69 year old patient with node negative breast cancer, the absolute survival benefit will be in the 2% range and the disease free survival gain approximately 6 months.2,3 The probability of severe toxicity by chemotherapy also varies among individual patients. For example, older patients have a greater incidence of congestive heart failure associated with anthracycline treatment when compared with younger patients, and clinical factors, such as age, baseline fatigue, depression, and functional status are associated with a higher risk of chemotherapy related cognitive decline.4–6

There is an increasing recognition that patients’ preferences should play an important role in medical treatment decisions, yet very few data exist regarding patients’ preferences for modern adjuvant chemotherapy.7 Older studies suggested that most patients with early breast cancer were willing to receive 6 months of adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil (CMF) chemotherapy for modest survival benefits (most women would have accepted 3–6 months extension of life), even when acknowledging potential adverse effects. 3,8–10 In addition, it has been suggested that physicians frequently do not necessary share patients’ views, sometimes being less likely to recommend chemotherapy for a small chance of benefit.9,11

With patients playing a more active role in their care as well as novel therapies having different toxicities, preferences could have changed over time. To determine early stage breast cancer patients’ views on the survival benefit needed to justify 6 months of chemotherapy, we surveyed patients in the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Protocol 5103 (E5103), a phase III trial in which all patients were randomized to receive at least a current standard adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy regimen (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide and paclitaxel [ACT]) with either placebo or one of two arms which combined ACT chemotherapy with two different durations of bevacizumab. We also examined physicians’ preferences regarding the survival benefit needed to justify 6 months of chemotherapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data source

All patients enrolled on E5103 between January 1, 2010 and June 8, 2010 were included in the Decision-Making/Quality of Life (QOL) component of this study. Institutional review board approval for the clinical trial was received through participating sites for study participation, and written informed consent was obtained from participants prior to study enrollment.

Surveys

Serial surveys were administered at baseline and 18 months after enrollment to examine potential long-term effects of the treatments on patients’ quality of life. The 18-month survey included questions, which had been previously pilot tested, focused on preferences for receiving chemotherapy. These questions are the basis of this report. In addition, a parallel physicians’ survey was sent to doctors who enrolled patients on E5103. Six questions asked if 6 months of chemotherapy would be worthwhile for a 1, 2, 6, 9, 12, and 24 month survival benefit with 3 possible answers for each question: 1) yes, definitely worthwhile 2) yes, maybe worthwhile 3) no, not worthwhile. Using life expectancy gain is a well-established method for eliciting preferences for chemotherapy.9,10,12

Data collection

Patients’ surveys were completed by telephone interview by centralized staff. Patients were mailed a copy of the survey two weeks prior to the phone interview. Most patients filled it out before the interview and the interview served to collect the answers. If not completed ahead of time or if the patient did not have a copy, survey questions were read aloud. Patients could ask questions about the survey at any point and were allowed to skip questions they were not comfortable answering.

Physicians were emailed a link to a brief web-based survey of their background and practice and the preference items modified as recommendations for a patient.

Statistical Methods

The primary outcomes of interest were the proportion of patients/physicians willing to consider chemotherapy (yes, [definitely worthwhile OR maybe worthwhile] vs. no, not worthwhile) for 2 or less months of survival benefit from receiving 6 months of chemotherapy and to not consider chemotherapy for 9 months of survival benefit from receiving 6 months of chemotherapy.

Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables (Wilcoxon rank sum test for ordered variables) was used to assess for univariate associations between willingness to consider 6 months of chemotherapy (no, yes) for 2 months of survival benefit and for 9 months of survival benefit for the covariates listed below. Using these same covariates from the patient analysis, multivariate logistic regression was used to assess for predictors of willingness to consider 6 months of chemotherapy: yes vs. no for 2 months of survival and no vs. yes for 9 months of survival. For physicians’ preferences, no multivariate logistic models were done due to small sample sizes. Covariates of interest in the patient analysis included age, race, marital status, education, hormone receptor status, grade, tumor size, nodal status, surgery, toxicity experienced (grade 3, 4, 5 adverse events defined by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.013), and treatment arm. Covariates of interest in the physician analysis included age, gender, race, years in profession, years in current practice, practice size, practice setting, number of new patients seen per month, number of new breast cancer patients seen per month, and number of patients physicians enroll on clinical trials per month. Two-sided p- values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

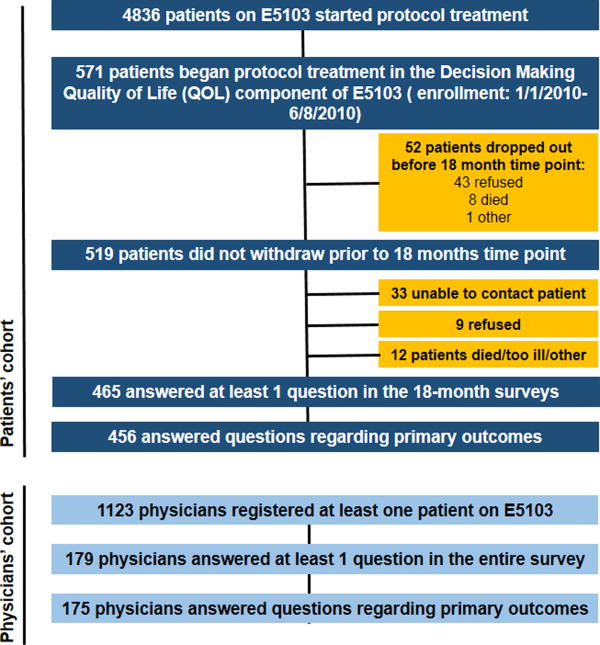

During the QOL enrollment period, 571 patients started protocol therapy and 519 who had not withdrawn at a timepoint prior to 18 months were contacted; 465 patients answered at least 1 question across all of the 18-month surveys, and 456 patients answered the 2 primary questions regarding willingness to receive chemotherapy for 2 and 9 months of survival benefit (87.8% response rate). From the 1123 physicians who registered at least one patient on E5103, 179 answered at least 1 question in this entire survey and 175 physicians answered the 2 primary questions regarding willingness to recommend chemotherapy (16% response rate). (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Patient Population. QOL: Quality of life, E5103: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Protocol 5103

The median patient age was 51.5 years (range, 25–76); most patients were white (86%). The majority of patients were married or had a partner (72%) and 44% of patients had at least a college degree. The majority had hormone receptor-positive disease (65%) and had nodal involvement (72%). (Table 1)

Table 1.

Patients’ Preferences Regarding Adjuvant Chemotherapy

| Cohort | Is 6 months of chemotherapy worthwhile for 2 months of benefit? | Is 6 months of chemotherapy worthwhile for 9 months of benefit? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| N (%) (N=456) |

No (%*) (N=193) |

Yes^ (%) (N=263) |

P^^ | No (%*) (N=53) |

Yes^ (%) (N=403) |

P^^ | |

| Age | 0.26 | 0.24 | |||||

| < 51.5 | 227 (50%) | 90 (40%) | 137 (60%) | 22 (10%) | 205 (90%) | ||

| ≥51.5 | 229 (50%) | 103 (45%) | 126 (55%) | 31 (14%) | 198 (86%) | ||

| Race | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||

| Other | 63 (14%) | 13(21%) | 50 (79%) | 1(2%) | 62 (98%) | ||

| White | 393 (86%) | 180 (46%) | 213 (54%) | 52 (13%) | 341(87%) | ||

| Marital status | 1.0 | 0.62 | |||||

| Married/partner | 309 (72%) | 133 (43%) | 176 (57%) | 35 (11%) | 274 (89%) | ||

| Not married | 119 (28%) | 51 (43%) | 68(57%) | 16 (13%) | 103 (87%) | ||

| Missing | 28 | ||||||

| Education | 0.02 | 0.30 | |||||

| <College | 239 (56%) | 91 (38%) | 148 (62%) | 32 (13%) | 207(87%) | ||

| ≥College | 190 (44%) | 93 (49%) | 97 (51%) | 19 (10%) | 171 (90%) | ||

| Missing | 27 | ||||||

| HR status | 0.43 | 0.35 | |||||

| HR− | 159 (35%) | 63 (40%) | 96 (60%) | 15 (9%) | 144 (91%) | ||

| HR+ | 297 (65%) | 130 (44%) | 167 (56%) | 38 (13%) | 259 (87%) | ||

| Grade | 0.56 | 1.0 | |||||

| 1 and 2 | 195 (44%) | 87 (45%) | 108 (55%) | 23 (12%) | 172 (88%) | ||

| 3 Missing |

250 (56%) 11 |

104 (42%) | 146 (58%) | 30 (12%) | 220 (88%) | ||

| Tumor size | 0.37 | 0.76 | |||||

| ≤ 2cm | 165 (36%) | 65 (39%) | 100 (61%) | 18 (11%) | 147 (89%) | ||

| > 2cm | 291 (64%) | 128 (44%) | 163 (56%) | 35 (12%) | 256 (88%) | ||

| Nodal status | 0.83 | 0.87 | |||||

| Negative | 126 (28) | 52 (41%) | 74 (59%) | 15 (12%) | 111 (88%) | ||

| Positive | 330 (72%) | 141 (43%) | 189 (57%) | 38 (12%) | 292 (88%) | ||

| Surgery | 0.92 | 1.0 | |||||

| Mastectomy | 262 (57%) | 110 (42%) | 152 (58%) | 31 (12%) | 231 (88%) | ||

| Breast conserving surgery | 194 (43%) | 83 (43%) | 111 (57%) | 22 (11%) | 172 (89%) | ||

| Treatment arm+ | 1.0 | 0.36 | |||||

| Placebo | 94 (21%) | 40 (43%) | 54 (57%) | 8 (9%) | 86 (91%) | ||

| Experimental (bevacizumab) | 362 (79%) | 153 (42%) | 109 (58%) | 45 (12%) | 317 (88%) | ||

| Toxicity | 0.47 | 0.21 | |||||

| No Grade 3,4,5 AE*** | 147 (32%) | 66 (45%) | 81 (55%) | 13 (9%) | 134 (91%) | ||

| Grade 3, 4,5 AE | 309 (68%) | 127 (41%) | 182 (59%) | 40 (13%) | 269 (87%) | ||

Footnotes/Abbreviations:

Row percentages shown,

HR, Hormone receptor (Defined as positive if estrogen receptor-positive or progesterone receptor-positive. Defined as negative if estrogen receptor-negative and progesterone receptor-negative),

AE: adverse events defined by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0. 13

includes yes definitely and yes, maybe worthwhile.

based on fisher exact test among non missing. Logistic regression model not shown.

The median physician age was 50 years (range, 35–70), 60% were males, and the vast majority were white (83%). Median years in the profession was 16.5 (range, 3–38), the majority were in academia (62%), and most of them saw ≥ 16 new patients per month (56%) and ≥ 5 new breast cancer patients per month (79%). (Table 2)

Table 2.

Physicians’ Preferences Regarding 6 Months of Adjuvant Chemotherapy

| Cohort | Is 6 months of chemotherapy worthwhile for 2 months of benefit? | Is 6 months of chemotherapy worthwhile for 9 months of benefit? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| N (%) (N=175) |

No (%*) (N=108) |

Yes^ (%*) (N=67) |

P** | No (%*) (N=9) | Yes^ (%*) (N=166) |

P** | |

| Age | 0.14 | 0.73 | |||||

| < 50 | 78 (48%) | 45 (58 %) | 33 (42 %) | 5 (6%) | 73 (94%) | ||

| ≥50 Missing |

85 (52%) 12 |

59 (69%) | 26 (31%) | 4 (5%) | 81 (95%) | ||

| Gender | 0.06 | 1.0 | |||||

| Male | 105 (64%) | 73 (70 %) | 32 (30 %) | 6 (6%) | 99 (92%) | ||

| Female Missing |

58 (36%) 12 |

31 (53%) | 27 (47%) | 3 (5%) | 55 (95%) | ||

| Race | 0.08 | 0.64 | |||||

| Other | 27 (17%) | 13 (48%) | 14(52%) | 2 (7%) | 25 (93%) | ||

| White Missing |

136 (83%) 12 |

91 (67%) | 45(33%) | 7 (5%) | 129 (95%) | ||

| Years in profession | 0.10 | 0.75 | |||||

| <16.5 | 82 (50%) | 47 (57%) | 35 (43%) | 4 (5%) | 78 (95%) | ||

| ≥16.5 Missing |

81 (50%) 12 |

57 (70%) | 24 (30%) | 5 (6%) | 76 (94%) | ||

| Years in current practice | 0.05 | 1.0 | |||||

| <10.5 | 82 (50%) | 46 (56%) | 36(44%) | 5 (6%) | 77 (46%) | ||

| ≥10.5 Missing |

81 (50%) 12 |

58 (72%) | 23 (28%) | 4 (5%) | 77 (46%) | ||

| Practice size | 0.34 | 1.0 | |||||

| Solo | 3 (2%) | 2(66%) | 1 (33%) | 1 (33%) | 2 (66%) | ||

| Small (<5) | 21(13%) | 11 (52%) | 10 (48%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (100%) | ||

| Large (≥5) Missing |

139 (85%) 12 |

91 (65%) | 48 (35%) | 8 (6%) | 131 (94%) | ||

| Practice setting | 0.76 | 0.98 | |||||

| Private | 61 (38%) | 38 (62%) | 23 (38%) | 3 (5%) | 58 (95%) | ||

| Academic affiliated | 55 (34%) | 35 (64%) | 20 (36%) | 4(7%) | 51 (93%) | ||

| Academic full time Missing |

46 (28%) 13 |

30 (65%) | 16 (35%) | 2 (4%) | 44 (96%) | ||

| New patients/month | <0.01 | 0.62 | |||||

| 0–5 | 3 (2%) | 2(66%) | 1 (33%) | 1 (33%) | 2 (67%) | ||

| 6–10 | 19 (12%) | 8 (42%) | 11(58%) | 0(0%) | 19 (100%) | ||

| 11–15 | 50 (31%) | 29 (58%) | 21(42%) | 2 (4%) | 48 (96%) | ||

| 16–20 | 45 (28%) | 28 (46%) | 17 (25%) | 3 (7%) | 42 (93%) | ||

| >20 Missing |

46 (28%) 12 |

37 (34%) | 9 (13%) | 3 (7%) | 43 (93%) | ||

| New breast cancer patients/month | 0.70 | 0.12 | |||||

| 0 | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 2(100%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) | ||

| 1–4 | 33 (20%) | 23 (69%) | 10 (31%) | 1 (3%) | 32 (97%) | ||

| 5–10 | 73 (45%) | 44 (60%) | 29(40%) | 3 (4%) | 70 (96%) | ||

| 11–15 | 31 (19%) | 21 (68%) | 10 (32%) | 2 (6%) | 29 (94%) | ||

| >15 Missing |

24 (15%) 12 |

16 (67%) | 8 (33%) | 3 (13%) | 21 (87%) | ||

| Patients on clinical trials/month | 0.46 | 0.19 | |||||

| 0 | 4 (2%) | 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (100%) | ||

| 1–4 | 137 (84%) | 87 (64%) | 50 (36%) | 7 (5%) | 130 (95%) | ||

| 5–10 | 19 (12%) | 12(63%) | 7 (37%) | 1 (5%) | 18 (95%) | ||

| 11–15 | 1 (1%) | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | ||

| >15 Missing |

2 (1%) 12 |

2 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | ||

Footnotes/Abbreviations:

Row percentages shown,

based on fisher exact test for categorical and Wilcoxon rank sum for ordered variables among non missing,

includes yes, definitely and yes, maybe worthwhile

Trade-offs of survival benefit needed to consider chemotherapy

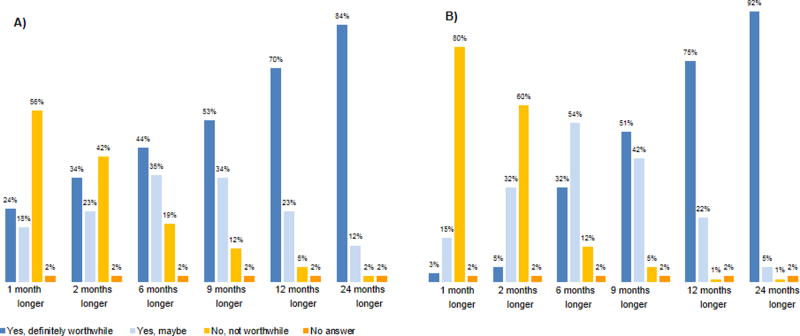

The proportion of patients willing to receive chemotherapy in exchange for survival benefit varied according to the magnitude of the survival benefit considered; nevertheless, we found considerable variation in patients’ preferences particularly for modest survival benefits. A substantial minority of patients (24%) would consider 6 months of chemotherapy definitely worthwhile for 1 month survival benefit, 18% would possibly consider it, and 56% would not. For 2 months of benefit, 57% would consider chemotherapy (34% definitely worthwhile and 23% would possibly consider it) and 42% would not.

About half of patients considered 6 months of chemotherapy definitely worthwhile and 34% would possibly consider it for 9 months benefit. The percentage considering chemotherapy definitely worthwhile increased with greater benefit, but did not reach 100%, even with 24 months survival benefit.

Overall (n=456), fewer people are saying ‘no’ to 9 months of benefit (12% [53/456]) vs. to 2 months of benefit (42% [193/456]).

Physicians’ preferences also varied particularly for modest survival benefits, but this variation was less pronounced compared to what was observed among patients. Physicians were less likely to accept chemotherapy for a small chance of benefit (e.g. 34% of patients vs. 5% of physicians would definitely consider chemotherapy worthwhile for 2 months of benefit). For greater benefit, patients’ and physicians’ choices were similar (84% of patients vs. 92% of physicians would definitely consider chemotherapy worthwhile for 24 months benefit). (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Trade-Offs of Survival Benefit Needed to Consider Chemotherapy Worthwhile. A) Patients’ Preferences B) Physicians’ Preferences

Patients’ preferences: Factors associated with trade-offs

A lower proportion of white patients were willing to consider 6 months of chemotherapy for 2 months of survival benefit when compared with patients of other race (54% [213/393] vs 79% [50/63], respectively; P < .01). Thirteen percent (52/393) of white patients were not willing to consider chemotherapy for 9 months of benefit versus 2% (1/63) of patients of other race (P < .01).

In addition, more educated (≥ college) patients were also less likely to consider chemotherapy for 2 months of benefit when compared with less educated patients (< college) (51% [97/190] vs. 62% [148/239], p=0.02), but education was not associated with willingness to not consider 9 or more months of benefit. (Table 1) These same covariates remained significant in the multivariate logistic regression to assess association with 2 month and 9 month survival benefit (results not shown).

In this study we did not find substantial trade-off differences for willingness to consider chemotherapy for 2 months of benefit or to not consider it for 9 months of benefit by tumor features, treatment characteristics (type of surgery, ACT with or without bevacizumab), or toxicity experienced on study (Grade 3, 4, 5 adverse events).

Physicians’ preferences: Factors associated with trade-offs

A lower proportion of physicians who see > 20 new patients/month would recommend chemotherapy for 2 months of survival benefit when compared with physicians who see fewer new patients/month (p<0.01). A lower proportion of physicians with ≥ 10.5 years in their current practice said that they would recommend chemotherapy for 2 months of benefit when compared with physicians with < 10.5 years in their current practice (28% [23/81] vs. 44% [36/82]) (p=0.05). There was a trend towards a higher proportion of female physicians recommending chemotherapy for 2 months of benefit when compared with male physicians (47% [27/58] vs. 30% [32/105], p=0.06), and for non-white doctors to recommend chemotherapy for 2 months of benefit when compared with white doctors (52% [14/27] vs. 33% [45/136], p=0.08).

No differences in other features (age, years in profession, practice size, new breast cancer patients per month, patients on clinical trials per month) were found with willing to recommend 6 months of chemotherapy for 2 months of benefit. Because the vast majority of physicians would recommend chemotherapy for 9 months of benefit, we had limited ability to find associations between those who would not recommend vs. those who would recommend it for 9 months of benefit.

DISCUSSION

Over the last decade, increasing attention to consumer satisfaction in medicine in addition to patients’ desires to actively participate in their medical decision process has promoted the consensus that a ‘quality decision in medicine is the one that takes into account patients’ preferences and in which patients are informed and receive treatments to match their goals’.7,14 Involving patients in treatment decisions is increasingly recognized as ‘the right to autonomy’.7 In a time of treatment guidelines and pathways, patients vary in the value they place on potential benefits of a toxic treatment such as chemotherapy.10 Our study, which demonstrated such heterogeneity in patient preferences, focused on a population of patients who enrolled in a clinical trial and who were treated with a modern chemotherapy regimen (ACT), and replicates studies done 20 years ago among breast cancer survivors mainly treated with CMF. Our findings are consistent with these prior data, showing that variation in patient’s preferences persist even with changing times and toxicities, and re-emphasizing the need of involving patients in the medical decision process. Several points can be taken from our data that support this.

First, it suggests that for women for whom the benefit of chemotherapy may be modest and questionable there is substantial variability in patients’ preferences. Many women are willing to consider 6 months of chemotherapy for 2 months of benefit (57%), but a substantial minority would not (42%). Old studies had similar results.3,8–10 For example, Lindley et al published a study in 1998, which evaluated 239 breast cancer patients with no evidence of recurrence 2–5 years after start of adjuvant treatment,9 and found that 47% of patients were willing to receive 6 months of chemotherapy for an additional 3 months of life9 and likewise, Ravdin et al reported that among 318 breast cancer survivors, >40% of women who had received adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer would accept adjuvant chemotherapy in exchange of 3 months of life.10

Second, consistent with prior studies,3,9,10,14,15 we found that although patient preferences for chemotherapy increase as benefits increase, a small minority (2%) of patients will not want to receive chemotherapy even for a 2 year survival benefit.

Third, our data also show that patients’ and providers’ preferences are not concordant for modest survival benefits. This was observed with prior oncology and non oncology studies,9,11,16–20 which often report that the degrees of benefit that physicians feel as not significant are different from those reported by patients. 9,11,16–20

Finally, our study suggests that some of this variability in patients’ preferences may be associated with social and cultural features; race and education were significantly associated with patients’ choices, and may generate insights on what drives patients’ preferences.

Although this study was able to very successfully capture patients’ preferences in a large cohort of subjects (87.8% response rate) treated with modern adjuvant chemotherapy, we acknowledge several limitations. First, patients who participated in this survey were sampled from a large clinical trial and therefore, there may be concerns about generalizability of our results. Our patients do not represent the typical patient with early breast cancer handling chemotherapy decisions. Our population was younger (median age, 51.5 years) and better educated (44% had at least a college education).7,21 In addition, all patients had high risk disease, for which there is usually a strong indication for anthracycline–taxane based chemotherapy (and all of the patients in our study received chemotherapy).7,21 It is also possible that patients who have chosen to have chemotherapy (and in addition to participate on a trial) may overestimate the value of chemotherapy when compared with those who choose not to take it (and not to participate on a trial). 7,21 It is also likely, that different durations of chemotherapy (e.g. shorter duration regimens such as 3 months regimens) could impact willingness to receive chemotherapy. Second, prior experiences suggest that patients’ views are different over time and are influenced by their past. When capturing patients’ experiences regarding chemotherapy after they have received chemotherapy, patients may be likely to be less apprehensive about chemotherapy-related toxicity and more likely to want to believe that the prior decision was right, both of which may have influenced their response in the surveys.9,10 Third, the way the question was framed may influence the answer, Lindley et al13 and Slevin et al14 examined both the life expectancy gain and increase in survival percentage that would make 6 months of chemotherapy worthwhile. In both studies, the same patients that accepted just 1% improvement in cure rate sometimes needed a benefit of 12 months in terms of survival prolongation.9,13 Our cognitive testing similarly suggested that patients had widely varying interpretations of, for example, a 2% or 10% survival increase, whereas their interpretation of a 6 or 12 month extension of life was fairly consistent. As a result, we selected life expectancy gained as the approach to elicit preferences in this study. It should be noted, by choosing this approach we are not advocating months of life expectancy gained as a way to communicate risk, rather just highlighting variability in patients preferences. Fourth, our study did not capture all factors associated with patients preferences (e.g. we did not have ability to evaluate the contribution of patient doctor interaction). Fifth, the physicians’ survey response rate was low and therefore, these data only can be read as illustrative. Finally, although our results suggest aggregate differences in patients and physicians choices, we did not conduct individual analyses to understand how preferences of each specific patient were incongruent with her provider choice, or either how this impacted patient distress.

Prior studies suggested that patients’ preferences are not being taken into consideration when chemotherapy decisions are being made even if it is widely accepted that a shared patient-doctor medical decision making model is ideal.14 In this setting, our findings have important implications. The decision about a modern type of chemotherapy is ‘preference’ sensitive, and therefore although evidence and clinical guidelines are essential, eliciting and understanding his or her comfort level with the benefits and risks of chemotherapy remains critical to determine the best approach to treatment. There is a need for some flexibility for clinicians to incorporate patients’ preferences when selecting treatments.7,21 Developing methods of explaining treatment decisions to patients that promote better patient-physician communication (e.g. Adjuvant! Online) and obtain patients’ preferences, constitutes a high priority of research.7,9,22 As demonstrated in this study, this is particularly relevant in situations where the benefits of chemotherapy are modest, but may also be meaningful for those for which the benefits are substantial.

Condensed abstract.

Among patients who received contemporary adjuvant chemotherapy in a multicenter trial, we found substantial variation in preferences regarding survival benefit worth undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy. Engaging patients preferences regarding risks/benefits of treatment, is critical in patient-centered medical decision making and care.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This study was coordinated by the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (Robert L. Comis, MD and Mitchell D. Schnall, MD, PhD, Group Co-Chairs) and supported in part by Public Health Service Grants CA180794, CA23318, CA66636, CA180820, CA21115, CA180867, CA180795, CA49883, CA180791, CA180790, CA13650, CA180816, CA025224, UCA031946, CA077651, CA180790, CA180791, CA180821, and from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services. This work has also been supported by a Susan G Komen Promise Award (PI: Schneider). Its content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure:

Dr. Dang has received research funding from Roche-Genentech and Puma.

Dr. Sepucha received salary support as a Medical editor from Informed decisions Foundation, part of Healthwise and funding from Susan G Komen.

Dr. Miller received funding from NCI and Susan G Komen.

Dr. Schneider received funding from Susan G Komen.

No conflict of interest disclosures from other authors.

Contributorship statement:

Conceptualization: Formulation of overarching research goals and aims: Ines Vaz-Luis MD, MSc, Anne O’Neill PhD, Karen Sepucha PhD, Kathy D Miller MD, Emily Baker, Chau T Dang MD, Donald W Northfelt MD, Eric P Winer MD,George W Sledge MD, Bryan Schneider MD, Ann H Partridge MD, MPH

Methodology: Development or design of methodology; creation of models: Ines Vaz-Luis MD, MSc, Anne O’Neill PhD, Karen Sepucha PhD, Kathy D Miller MD, Emily Baker, Chau T Dang MD, Donald W Northfelt MD, Eric P Winer MD,George W Sledge MD, Bryan Schneider MD, Ann H Partridge MD, MPH

Formal analysis: Application of statistical, mathematical, computational, or other formal techniques to analyze or synthesize study data: Anne O’Neill PhD

Investigation: Research and investigation process, specifically performing the experiments, or data/evidence collection: Ines Vaz-Luis MD, MSc, Anne O’Neill PhD, Karen Sepucha PhD, Kathy D Miller MD, Emily Baker, Chau T Dang MD, Donald W Northfelt MD, Eric P Winer MD,George W Sledge MD, Bryan Schneider MD, Ann H Partridge MD, MPH

Resources: Provision of study materials, reagents, materials, patients, laboratory samples, animals, instrumentation, computing resources, or other analysis tools: Ines Vaz-Luis MD, MSc, Anne O’Neill PhD, Karen Sepucha PhD, Kathy D Miller MD, Emily Baker, Chau T Dang MD, Donald W Northfelt MD, Eric P Winer MD,George W Sledge MD, Bryan Schneider MD, Ann H Partridge MD, MPH

Data curation: Management activities to annotate (produce metadata), scrub data and maintain research data (including software code, where it is necessary for interpreting the data itself) for initial use and later re-use: Anne O’Neill PhD,Emily Baker BA

Writing – original draft: Preparation, creation and/or presentation of the published work, specifically writing the initial draft (including substantive translation): Ines Vaz-Luis MD, MSc, Anne O’Neill PhD, Karen Sepucha Phd, Ann H Partridge MD, MPH

Writing – review and editing: Preparation, creation and/or presentation of the published work by those from the original research group, specifically critical review, commentary or revision – including pre- or post-publication stages/ Ines Vaz-Luis MD, MSc, Anne O’Neill PhD, Karen Sepucha PhD, Kathy D Miller MD, Emily Baker, Chau T Dang MD, Donald W Northfelt MD, Eric P Winer MD,George W Sledge MD, Bryan Schneider MD, Ann H Partridge MD, MPH

Visualization: Preparation, creation and/or presentation of the published work, specifically visualization/data presentation: Ines Vaz-Luis MD, MSc, Anne O’Neill PhD, Karen Sepucha PhD, Kathy D Miller MD, Emily Baker, Chau T Dang MD, Donald W Northfelt MD, Eric P Winer MD,George W Sledge MD, Bryan Schneider MD, Ann H Partridge MD, MPH

Supervision: Oversight and leadership responsibility for the research activity planning and execution, including mentorship external to the core team: Ines Vaz-Luis MD, MSc, Ann H Partridge MD, MPH

Project administration: Management and coordination responsibility for the research activity planning and execution: Ines Vaz-Luis MD, MSc, Ann H Partridge MD, MPH

Funding acquisition: Acquisition of the financial support for the project leading to this publication: Bryan Schneider MD, Ann H Partridge MD, MPH

References

- 1.Giordano SH, Lin YL, Kuo YF, Hortobagyi GN, Goodwin JS. Decline in the use of anthracyclines for breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(18):2232–2239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peto R, Davies C, Godwin J, et al. Comparisons between different polychemotherapy regimens for early breast cancer: meta-analyses of long-term outcome among 100,000 women in 123 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012;379(9814):432–444. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61625-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simes RJ, Coates AS. Patient preferences for adjuvant chemotherapy of early breast cancer: how much benefit is needed? Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Monographs. 2001;(30):146–152. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swain SM, Whaley FS, Ewer MS. Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin: a retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer. 2003;97(11):2869–2879. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, McDonald BC, et al. Longitudinal assessment of cognitive changes associated with adjuvant treatment for breast cancer: impact of age and cognitive reserve. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(29):4434–4440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassett MJ, O’Malley AJ, Pakes JR, Newhouse JP, Earle CC. Frequency and cost of chemotherapy-related serious adverse effects in a population sample of women with breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2006;98(16):1108–1117. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333(7565):417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38926.629329.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duric V, Stockler M. Patients’ preferences for adjuvant chemotherapy in early breast cancer: a review of what makes it worthwhile. The lancet oncology. 2001;2(11):691–697. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00559-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindley C, Vasa S, Sawyer WT, Winer EP. Quality of life and preferences for treatment following systemic adjuvant therapy for early-stage breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1998;16(4):1380–1387. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ravdin PM, Siminoff IA, Harvey JA. Survey of breast cancer patients concerning their knowledge and expectations of adjuvant therapy. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1998;16(2):515–521. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Connor AM. Effects of framing and level of probability on patients’ preferences for cancer chemotherapy. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1989;42(2):119–126. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandelblatt JS, Sheppard VB, Hurria A, et al. Breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy decisions in older women: the role of patient preference and interactions with physicians. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(19):3146–3153. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. Version 4.0. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slevin ML, Stubbs L, Plant HJ, et al. Attitudes to chemotherapy: comparing views of patients with cancer with those of doctors, nurses, and general public. BMJ. 1990;300(6737):1458–1460. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6737.1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zimmermann C, Baldo C, Molino A. Framing of outcome and probability of recurrence: breast cancer patients’ choice of adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT) in hypothetical patient scenarios. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2000;60(1):9–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1006342316373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashby J, O’Hanlon M, Buxton MJ. The time trade-off technique: how do the valuations of breast cancer patients compare to those of other groups? Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 1994 Aug;3(4):257–265. doi: 10.1007/BF00434899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cotler SJ, Patil R, McNutt RA, et al. Patients’ values for health states associated with hepatitis C and physicians’ estimates of those values. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2001;96(9):2730–2736. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brothers TE, Cox MH, Robison JG, Elliott BM, Nietert P. Prospective decision analysis modeling indicates that clinical decisions in vascular surgery often fail to maximize patient expected utility. The Journal of surgical research. 2004;120(2):278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stalmeier PF, van Tol-Geerdink JJ, van Lin EN, et al. Doctors’ and patients’ preferences for participation and treatment in curative prostate cancer radiotherapy. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(21):3096–3100. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pieterse AH, Baas-Thijssen MC, Marijnen CA, Stiggelbout AM. Clinician and cancer patient views on patient participation in treatment decision-making: a quantitative and qualitative exploration. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(6):875–882. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CN, Wetschler MH, Chang Y, et al. Measuring decision quality: psychometric evaluation of a new instrument for breast cancer chemotherapy. BMC medical informatics and decision making. 2014;14:73. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-14-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.https://www.adjuvantonline.com/ Accessed on 02/14/2017