Abstract

Extragonadal teratomas are rare, and localization in the endometrium and cervix is exceptional, with only up to 10 case reports documented so far in the English literature. We present here the case of a 46-year-old patient who presented with simultaneous immature teratoma in the endometrium and mature teratomas in the ovary in association with gliomatosis peritonei but with no evidence of gestational origin; she subsequently developed multiple solid mature teratomas in the cervix and parauterine tissue. No other similar cases have been previously reported to our knowledge. There are many similarities between the patient’s pattern of recurrence and “growing teratoma syndrome (GTS).” Although the patient was not treated with chemotherapy after her first presentation and this case does not meet formal criteria for GTS, we believe that the pattern and histology of recurrences in this case represent a variant of GTS. Considering that the initial presentation in this case was endometrial and ovarian makes the occurrence of GTS-like syndrome even more unique.

Teratomas are tumors that usually develop in the gonads from primordial germ cells (1), but they can also arise in extragonadal locations. Extragonadal teratomas are rare (comprising 1–2% of all germ cell tumors) and can develop anywhere along the migration route of the germ cells (2). Localization in the endometrium and cervix is exceptional, with only up to 10 case reports documented so far in the English literature (3–7). It has been suggested that the origin of this type of tumor in the cervix and/or endometrium may be related to residual fetal tissue or implantation of such structures, suggesting that these tumors could be gestational rather than true germinal teratomas (8).

We present an exceptional case of a 46-year-old patient who presented with simultaneous immature teratoma in the endometrium and mature teratomas in the ovary in association with gliomatosis peritonei; she subsequently developed multiple solid mature teratomas in the cervix and parauterine tissue. No other similar cases have been previously reported to our knowledge.

Case report

A 46-year-old patient (gravida 2, para 1) with morbid obesity (weight, 146 kg; height, 160 cm) presented in October 2003 to the Gynecology Department for vaginal bleeding. Her past medical history included hypertension with hypertensive heart disease, diabetes mellitus type 2. The patient had a normal pregnancy carried to term 22 years prior to the consultation.

On ultrasonography, the patient was found to have an endometrial polypoid tumor, 25 mm in diameter, associated with a left ovarian tumor, 70 mm in diameter, with a cystic appearance. Endometrial curettage was performed in November 2003, revealing fragments of secretory endometrium together with fragments of immature neural tissue compatible with grade 1 immature teratoma (Armed Forces Institute of Pathology [AFIP] and World Health Organization [WHO] 2012 grading system) (Figure 1). No other neoplastic germ cell elements, such as yolk sac tumor, dysgerminoma, embryonal carcinoma, choriocarcinoma or polyembryoma, was detected.

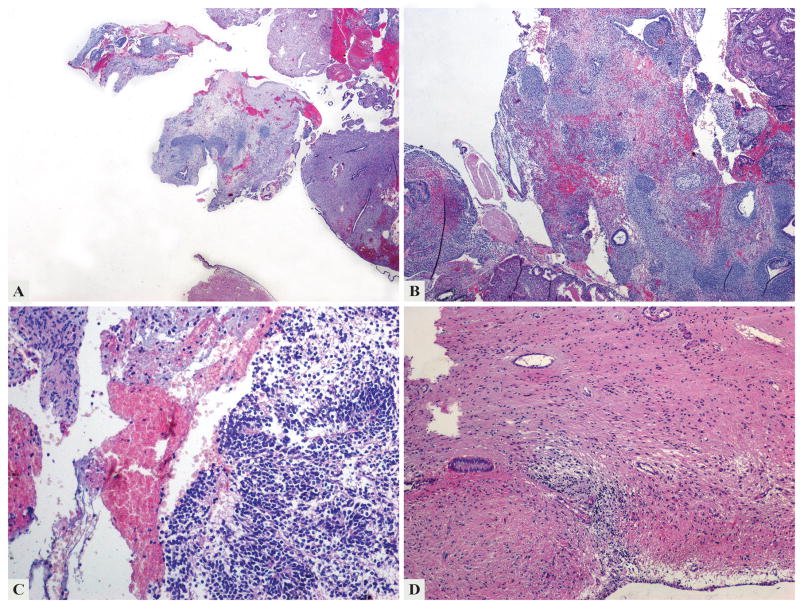

Figure 1.

The first specimen examined in 2003 contained multiple fragments of secretory endometrium and tumor tissue (a). The tumor was mainly composed of mature epithelial and mesenchymal tissue (b), but immature neuroectodermal components with poorly formed rosettes (c) and mature glial component surrounding endometrial glands (d) were also present.

Due to continuous vaginal bleeding, she underwent a second curettage in December 2003, and microscopic examination revealed a recurrent teratoma of the endometrium that lacked immature elements. The tumor was composed of lobules of mature glial, adipose and osseous tissue admixed, surfaced by squamous epithelium (Figure 2). She continued to bleed, and a hysteroscopic examination was performed in February 2004. Her examination revealed an ulcerated polypoid tumor occupying two-thirds of her uterine cavity, which was hysteroscopically excised in March 2004. One month later, an endometrial biopsy revealed the presence of a residual/recurrent mature teratoma, but the patient did not receive any oncologic treatment. In June 2004, she underwent a biopsy of the left ovarian tumor, interpreted as a mature ovarian teratoma, and multiple biopsies from the anterior abdominal wall, broad left ligament, the vesicouterine pouch and the sigmoid, all represented microscopically by mature glial tissue compatible with gliomatosis peritonei (grade 0) (Figure 3). The ovarian tumor was surgically removed in July 2004 and was diagnosed as a solid mature ovarian teratoma associated with gliomatosis peritonei in the pouch of Douglas and omentum. Subsequently, she underwent an ultrasound examination in 2005 for a cystic tumor involving the right ovary and multiple peritoneal biopsies that revealed gliomatosis peritonei.

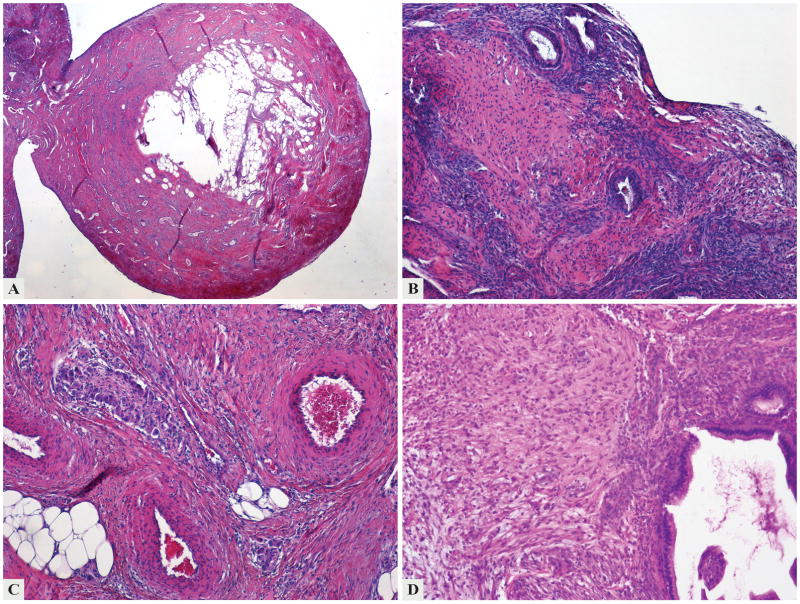

Figure 2.

The second curettage examined in 2003 revealed a recurrent mature teratoma of the endometrium lined by squamous epithelium on the surface (a) and containing endometrial glands (b) and other mature type tissues such as ganglion cells, adipose (c) and glial tissue (d).

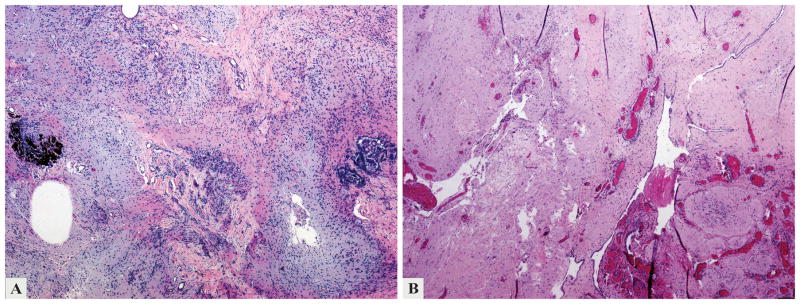

Figure 3.

Biopsy from the anterior abdominal wall (2004), compatible with gliomatosis peritonei, contained mostly mature glial tissue. Focally, choroid plexus and melanin pigment (a) were present in a submesothelial distribution (b).

In 2015, clinical examination and ultrasonography revealed the presence of two polypoid structures in the cervix, two similar ones in the left parauterine space (attached to the serosa), and a right ovarian cystic tumor, measuring 70 mm in greatest dimension. Total hysterectomy, a right salpingo-oophorectomy, and a right hemicolectomy (with jejunocolic anastomosis) were performed. Macroscopic examination of the total hysterectomy specimen revealed the presence of two polypoid nodules with smooth surfaces, soft consistency, and yellow color located in the endocervical canal, measuring 8 mm and 1 0mm, respectively, and two similar nodules attached to the serosa of the uterine corpus (12 mm and 15 mm, respectively) (Figure 4). Multiple foci of gliomatosis peritonei were present on the serosa of the large bowel. Microscopically, the nodules in the cervix were lined by endocervical and squamous epithelium and composed of mature, predominantly neural tissue admixed with adipose tissue, skin appendages with sebaceous glands, cartilage, and bronchial epithelium. The tumors were considered solid mature teratomas without immature components (Figure 5). The tumors involving the parauterine space had a similar microscopic appearance. (Molecular genotyping was performed using AmpFlSTR Profiler kit (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA). Fifteen different STR markers and the amelogenin locus (sex-determination) are co-amplified in a single reaction. Separation of the PCR products and fluorescence detection are performed on the ABI 3130 capillary electrophoresis instrument. The alleles of each locus from tumor tissue were compared with those from normal tissue). Genotyping results showed matching DNA in normal and neoplastic tissue (parauterine tumor), providing evidence against a gestational origin for the tumor. The right ovarian tumor was consistent with a sero-mucinous borderline tumor. The hemicolectomy specimen revealed multiple foci of gliomatosis peritonei on the serosal surface. The postoperative period was uneventful, and the patient is well 5 months after surgery, and without complications.

Figure 4.

Two polypoid nodules with smooth surfaces, soft consistency, and yellow color (of 8 mm and 10 mm, respectively) were located in the endocervical canal (right), and two similar nodules (of 12 mm and 15 mm, respectively) were attached to the serosa of the uterine corpus (left)

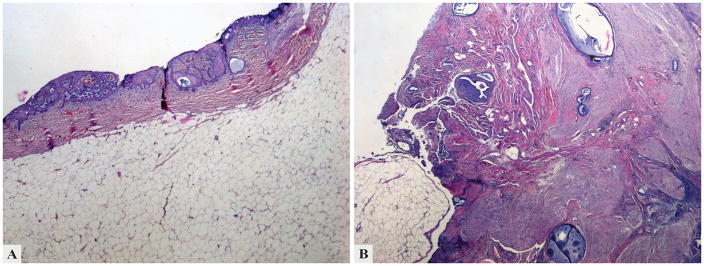

Figure 5.

This cervical solid mature teratoma nodule examined in 2015 is lined by endocervical and squamous epithelium (a) and composed of mature, predominantly neural tissue admixed with adipose tissue (b); entrapped endocervical glands are seen throughout the lesion.

Discussion

According to the WHO classification system, ovarian teratomas are subcategorized into immature teratoma, mature (solid or cystic) teratoma, and monodermal and highly specialized teratomas (9). Most ovarian teratomas (99%) are represented by mature cystic teratomas (known also as dermoid cyst) while mature solid teratomas are rare. Most of these tumors are ovarian and occur in children and young adults, while localization in the cervix or parauterine tissue has not yet been reported. In contrast, solid immature teratomas are represented by a mixture of immature tissues derived from the three germ layers. There are fewer than 10 reported cases of mature or immature teratomas located in the cervix and/or endometrium, and most of them have been interpreted to represent implantation of fetal tissue (2,4,6,7,10–13). We are aware of only one report of a primary immature solid teratoma in the endometrium (in association with endometrial adenocarcinoma in a 37-year-old patient), with all of the previously reported cases being of mature cystic type (7). Moreover, there is no report of an ovarian mature teratoma with metachronous development of multiple mature solid teratomas in the cervix and parauterine tissue.

The presence of peritoneal implants composed entirely of mature glial tissue occasionally may be observed in patients with immature or mature solid and cystic teratomas involving the ovary or other organs. They are composed primarily of mature astroglia and are of small size despite occasionally widespread distribution in the peritoneum. They can remain unchanged for life, and their presence does not affect prognosis. Their development is related to either direct seeding from a primary teratoma in the female genital tract or metaplasia from peritoneal stem cells (15). In our case, the patient developed multiple grade 0 peritoneal implants several months after the initial diagnosis (2003), and she continued to develop such implants for which she did not receive any oncologic treatment, since all implants were well differentiated and composed only of mature glial tissue.

There are many similarities between the patient’s pattern of recurrence and “growing teratoma syndrome (GTS).” The syndrome is defined by the presence of growing, mature teratoma with negative serum biomarkers that arises after surgical excision, during or after chemotherapy for a germ cell tumor (16–18). Although most literature reports focus on non-seminomatous testicular germ cell tumors, the syndrome also occurs after a diagnosis of ovarian germ cell tumors, with most cases having a component of immature teratoma at presentation. The interval between therapy and recurrence is approximately 2 years, although further recurrences can occur decades later. Secondary somatic malignancy and carcinoid tumors may also occur. According to a review by Malpica et al. (19), implants of ovarian GTS remain confined almost exclusively to the pelvis, abdomen, and the retroperitoneum and do not spread to distant sites. It is hypothesized that the occurrence of mature teratoma after treatment for a non-seminomatous germ cell tumor can be explained in three ways (20,21): 1) chemotherapy destroys only the immature malignant cells, leaving the mature benign teratomatous elements; 2) chemotherapy alters the cell kinetics toward transformation from a totipotent malignant germ cell toward a benign mature teratoma; and 3) an inherent and spontaneous differentiation of malignant cells into benign tissues, as was suggested in an experimental murine teratocarcinoma mouse model (21).

The main difference between the case presented here and typical examples of GTS is that the patient was not treated with chemotherapy after her first presentation. Although this case does not meet formal criteria for GTS, a case resembling GTS following surgical excision, but not chemotherapy, has been reported (22). Considering that the initial presentation in this case was endometrial and ovarian makes the occurrence of GTS-like syndrome even more unique.

One can raise four possible origins of the endometrial and cervical tumors: displaced germinal cells, derivation from pluripotential stem cells, a metaplastic process, or residual fetal tissue. Most of the cases in which a metaplastic process can occur after trauma or inflammation do not contain a mixture of tissues but usually cartilage or bone tissue only (23). In this case, there was no evidence of gestational origin, leaving open the possibility of derivation from pluripotent germinal stem cells.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Dr. Soslow is supported in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Talerman A, Vang R. Germ cell tumors of the ovary. In: Kurman RJ, Hendrick Ellenson L, Ronnett BM, editors. Blaustein’s pathology of the female genital tract. 6. Springer; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell MC, Schmidt-Grimminger DC, Connor MG, et al. A cervical teratoma with invasive squamous cell carcinoma in an HIV-infected patient: a case report. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;60:475–9. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mann W. Zwei seltene gescgwulste des corpus uteri mitbemer-kungenzuihrerentstehungsweise (dreiblattriges, solidesteratom und medullores osteochondrom) Virchows Arch F Path Anat. 1929;273:663–92. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim S, Kim Y, Lee Y, et al. Mature teratoma of the uterine cervix with lymphoid hyperplasia. Pathol Int. 2003;53:327–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2003.01468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKenney JK, Heerema-McKenney A, Rouse RV. Extragonadal germ cell tumors: a review with emphasis on pathologic features, clinical prognostic variables, and differential diagnostic considerations. Adv Anat Pathol. 2007;14:69–92. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e31803240e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang WC, Lee MS, Ko JL, et al. Origin of uterine teratoma differs from that of ovarian teratoma: a case of uterine mature cystic teratoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2011;30:544–8. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31821c3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ansah-Boateng Y, Wells M, Poole DR. Coexistent immature teratoma of the uterus and endometrial adenocarcinoma complicated by gliomatosis peritonei. Gynecol Oncol. 1985;21:106–10. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(85)90240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tyagi SP, Saxena K, Rizvi R, et al. Foetal remnants in the uterus and their relation to other uterine heterotopia. Histopathology. 1979;3:339–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1979.tb03015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurman RJ, Carcangiu ML, Herrington CS, et al. WHO Classification of tumors of the female reproductive organs. IARC; Lyon: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dallenbach-Hellweg G, Wittlinger H. Benign solid teratoma of the uterus. Beitr Pathol. 1976;158:307–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khorsandi F, Anabitarte M. Immature solid teratoma of the uterine cervix. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1981;41:347–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1036807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin E, Scholes J, Richart RM, Fenoglio CM. Benign cystic teratoma of the uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;135:429–31. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(79)90720-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sissons MC, Foria B. Benign teratoma of the uterus. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;23:322–3. doi: 10.1080/01443610310000106028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwanaga S, Ishii H, Nagano H, et al. Mature cystic teratoma of the uterine cervix. Asia Oceania J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;16:363–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.1990.tb00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nogales FF, Preda O, Dulcey I. Gliomatosis peritonei as a natural experiment in tissue differentiation. Int J Dev Biol. 2012;56:969–74. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.120172fn. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Logothetis CJ, Samuels ML, Trindade A, Johnson DE. The growing teratoma syndrome. Cancer. 1982;50:1629–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19821015)50:8<1629::aid-cncr2820500828>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umekawa T, Tabata T, Tanida K, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome as an unusual cause of gliomatosis peritonei: a case report. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:761–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zagamé L, Pautier P, Duvillard P, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome after ovarian germ cell tumors. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(3 Pt 1):509–14. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000231686.94924.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Djordjevic B, Euscher ED, Malpica A. Growing teratoma syndrome of the ovary: review of literature and first report of a carcinoid tumor arising in a growing teratoma of the ovary. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1913–8. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318073cf44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nimkin K, Gupta P, McCauley R, et al. The growing teratoma syndrome. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:259–62. doi: 10.1007/s00247-003-1045-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong WK, Wittes RE, Hajdu ST, et al. The evolution of mature teratoma from malignant testicular tumors. Cancer. 1977;40:2987–92. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197712)40:6<2987::aid-cncr2820400634>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Synder RN. Completely mature pulmonary metastasis from testicular teratocarcinoma. Case report and review of literature. Cancer. 1969;24:810–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196910)24:4<810::aid-cncr2820240424>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newton CW, 3rd, Abell MR. Iatrogenic fetal implants. Obstet Gynecol. 1972;40:686–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]