Abstract

Previously, we demonstrated production of an active recombinant human N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfatase (rhGALNS) enzyme in Escherichia coli as a potential therapeutic alternative for mucopolysaccharidosis IVA. However, most of the rhGALNS produced was present as protein aggregates. Here, several methods were investigated to improve production and activity of rhGALNS. These methods involved the use of physiologically-regulated promoters and alternatives to improve protein folding including global stress responses (osmotic shock), overexpression of native chaperones, and enhancement of cytoplasmic disulfide bond formation. Increase of rhGALNS activity was obtained when a promoter regulated under σ s was implemented. Additionally, improvements were observed when osmotic shock was applied. Noteworthy, overexpression of chaperones did not have any effect on rhGALNS activity, suggesting that the effect of osmotic shock was probably due to a general stress response and not to the action of an individual chaperone. Finally, it was observed that high concentrations of sucrose in conjunction with the physiological-regulated promoter proU mod significantly increased the rhGALNS production and activity. Together, these results describe advances in the current knowledge on the production of human recombinant enzymes in a prokaryotic system such as E. coli, and could have a significant impact on the development of enzyme replacement therapies for lysosomal storage diseases.

Introduction

Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA (MPS IVA, Morquio A disease, OMIM 253000) is a rare autosomal-recessive disease characterized by the deficiency of the lysosomal enzyme N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate sulfatase (GALNS, EC 3.1.6.4) with an estimated incidence of 1:200,000 born alive1, 2. This enzyme is indispensable for the degradation of the glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) keratan sulfate and chondroitin-6-sulfate. The progressive accumulation of these GAGs within the lysosomes of multiple tissues such as ligaments, connective tissues, bone and cartilage, leads to the classical clinical manifestations of the disease including laxity of joints, skeletal dysplasia, hearing loss, corneal clouding, and pulmonary dysfunction, among others3.

Currently, the leading therapeutic option for MPS IVA is the enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) by using a recombinant enzyme produced in Chinese hamster ovaries (CHO) cells (elosulfase alfa)4. Although elosulfase alfa is a therapeutic option for MPS IVA patients, current limitations include5: (i) a limited effect on skeletal, corneal, and heart valvular tissues (ii) a short half-life of the enzyme and rapid clearance from the circulation (iii) immunological problems, and (iv) a high cost. An improved ERT with a long circulating enzyme and a bone-targeting enzyme have been proposed6, and a recombinant GALNS produced in other sources may potentially help to resolve some of the listed issues7.

The human GALNS complementary DNA is composed by 1569 bp, encoding a 522 amino acids peptide (herein known as precursor peptide). This protein undergoes several posttranslational modifications by the trafficking through the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus and lysosome. These posttranslational modifications include the removal of the signal peptide (first 26 amino acids −3 kDa), the active-site activation by the formylglycine-generating enzyme, the addition of two N-glycosylations, and the proteolytic processing to obtain a ∼58 kDa mature enzyme formed by two polypeptides of 40 kDa and 18 kDa8, 9. In the case of the recombinant GALNS produced in Escherichia coli and Pichia pastoris, it was reported a similar processing to that observed for the enzyme produced in mammalian cells9, 10.

E. coli has been extensively used as the prokaryotic model organism for production of proteins with therapeutic and industrial interest11–13. The key problem in the production of human recombinant proteins in this bacterial host is related with the lack of post-translational modifications, as glycosylations, and poor protein folding, leading to loss of enzyme activity and the formation of insoluble protein aggregates14.

Previously, we demonstrated the production of a recombinant human GALNS enzyme (rhGALNS) in E. coli BL21(DE3) as a potential therapeutic alternative for MPS IVA9, 15. However, most of the produced protein was present as protein aggregates. Culture conditions were optimized, including inductor concentrations and temperature shifts, which maximized rhGALNS activity, but most of its production was present in the insoluble protein fraction16. Here we explored different approaches to increase the production and activity of rhGALNS in E. coli. These approaches included the use of physiologically-regulated promoters to modulate gene expression, induction of osmoprotectants as helpers in protein folding, the overexpression of chaperone proteins, the improvement in the formation of disulfide bonds, and the combination of the different approaches to explore additive effects.

Results and Discussion

Effect of physiologically-regulated promoters on rhGALNS activity

There are several factors contributing to the formation of inclusion bodies in prokaryotic systems at the transcriptional level, which are generally attributed to a high transcriptional rate17 and transcription leakiness due to poor promoter repression18. The staple prokaryotic promoter used in recombinant protein production in E. coli is the lac promoter, which has been widely utilized due to its ability to be straightforwardly controlled with isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and tightly repressed via lacIq 19. Other promoters commonly used in recombinant protein production are thermal or chemically induced20. Previous studies demonstrated the production of active rhGALNS in E. coli BL21(DE3) using the tac promoter, a synthetic promoter created from the combination of promoters from the trp and lac operons, which is inducible by IPTG21. However, most of the rhGALNS was recovered from protein aggregates9, 16. We hypothesized that the expression of rhGALNS is either controlled poorly at the transcriptional level or it is highly overexpressed, which leads to the accumulation of rhGALNS as protein aggregates.

To facilitate the production process (i.e. avoiding the use of inductors) and considering a necessary strong regulation over rhGALNS expression, the promoters osmY and proU mod were selected for gene expression. These two promoters have been described to be tightly controlled under σ s, and to induce the gene transcription at the late-exponential and at the onset of stationary growth phases22, 23. The promoters osmY and proU mod were cloned to obtain the plasmids pGEXosmY and pGEXproUmod (Table 1 and Supplementary Data). Subsequently, the plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) for rhGALNS production as described in the Materials and Methods section. The cells were growth in M9 minimal media, and E. coli BL21(DE3)/pGEX-5X-GALNSopt was used as control.

Table 1.

List of plasmids used in this work.

| Plasmid | Description | Selection Marker | Source of reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| pGEX-5X-GALNSopt | pGEX-5X-3 plasmid encoding the enzyme N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfatase codon-optimized for expression in E. coli | AmpR | This study |

| pGEXosmY | Modification of the pGEX-5X-GALNSopt plasmid where the promoter tac was replaced by the osmY promoter with its corresponding RBS | AmpR | This study |

| pGEXproUmod | Modification of the pGEX-5X-GALNSopt plasmid where the promoter tac was replaced by the proU mod promoter with its corresponding RBS | AmpR | This study |

| pACYCDuet™-1 | Bicistronic plasmid used as a control and to clone all the chaperones used in this study | CmR | Novagen, Merck Milipore |

| pDuet::GroS | Plasmids for the overexpression of the genes groS, groL, groS and groL, dnaK, dnaJ, dnaK and dnaJ, ibpA, ibpB, ibpA and ibpB, dsbA, dsbB, dsbA and dsbB, grpE, and clpB (respectively) driven by the lac promoter. Backbone pACYCDuet™-1 | CmR | This study |

| pDuet::GroL | |||

| pDuet::GroSL | |||

| pDuet::DnaK | |||

| pDuet::DnaJ | |||

| pDuet::DnaKJ | |||

| pDuet::IbpA | |||

| pDuet::IbpB | |||

| pDuet::IbpAB | |||

| pDuet::DsbA | |||

| pDuet::DsbB | |||

| pDuet::DsbAB | |||

| pDuet::GrpE | |||

| pDuet::ClpB |

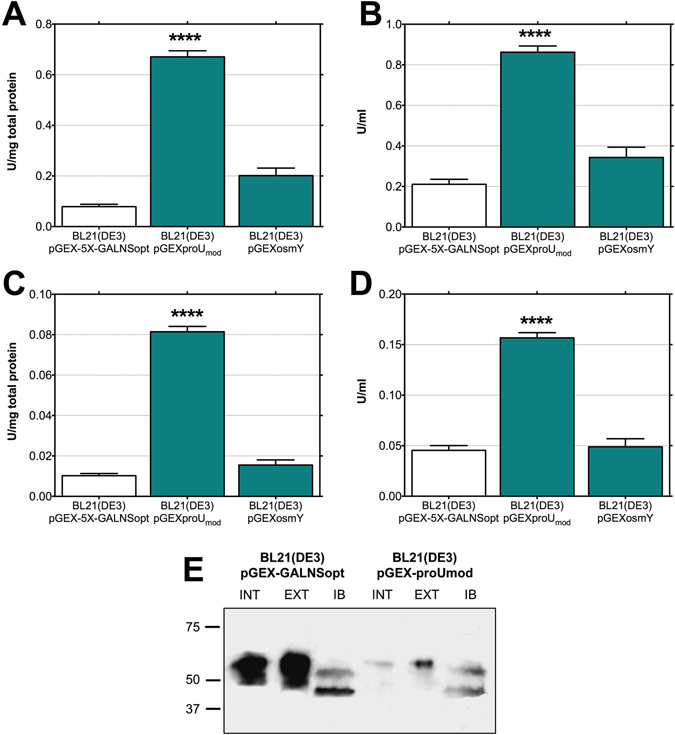

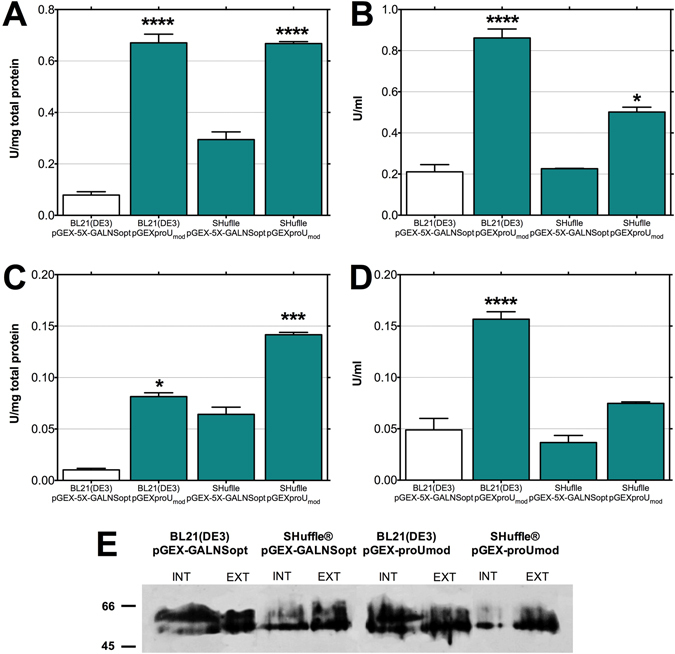

As shown in Fig. 1, we did not observe a statistically significant increment in rhGALNS activity, in comparison to the levels observed using the strain BL21(DE3)/pGEX-5X-GALNSopt, when gene expression was driven by the osmY promotor, either intra- or extracellularly. This promoter has been reported as a weak promoter strongly regulated by σ s 23, in correspondence to the low enzyme activities obtained. On the other hand, rhGALNS activity increased significantly when the proU mod promoter was used. The enzymatic activities obtained at the intracellular level (Fig. 1C and D) were 0.08 U/(mg total protein) and 0.16 U/mL, corresponding to increments of 695% and 245%, respectively, in comparison to the levels observed using the strain E. coli BL21(DE3)/pGEX-5X-GALNSopt. At the extracellular fraction, the enzyme activities, as shown in Fig. 1A and B, were 0.67 U/(mg total protein) and 0.86 U/mL of rhGALNS, equivalent to increments of 751% and 309%, respectively, in comparison to the levels observed using pGEX-5X-GALNSopt.

Figure 1.

Production of rhGALNS in E. coli BL21(DE3) using different promoters. (A) Specific activity in the extracellular fraction. (B) Volumetric activity in the extracellular fraction. (C) Specific activity in the intracellular fraction. (D) Volumetric activity in the intracellular fraction. Enzyme activity was assessed 24 hours after induction (no induction was necessary in the case of the promoters studied). A Student’s t-test was performed to assess significance, where (****) corresponds to a p-value < 0.0001. Specific activities are expressed as U rhGALNS/(mg total protein) and volumetric activities as U/ml. (E) Western blotting analysis of E. coli extracts. Here we evaluated the effect of the promoters tac and proU mod on the level expression of rhGALNS soluble protein at optimal (0.5 mM) IPTG concentration (in the case of tac) and 37 °C. Both soluble (intracellular [INT] and extracellular [EXT]) and protein aggregates (IB) fractions are shown. Samples from the intracellular fraction were normalized by the total protein amount, solubilized protein aggregates fractions were normalized by biomass, and the extracellular samples were normalized by culture volume. A non-cropped version of this figure can be found in the Supplementary Data.

It is important to highlight that secretion of rhGALNS is a process mediated by the human native GALNS signal peptide. Extracellular secretion of rhGALNS in E. coli BL21(DE3), associated to the presence of a native signal peptide, was previously observed16. In the study, by using a similar plasmid construction to the one used in this report (i.e. GALNS with a native signal peptide downstream of the glutathione S-transferase [GST]), it was observed that removal of the signal peptide completely abolished secretion of the recombinant enzyme. Those results suggested that GALNS signal peptide is recognized by E. coli secretion machinery, even if it is located downstream of the GST peptide. In addition, removal of signal peptide severely affected the activation process of rhGALNS16.

In order to evaluate the presence of rhGALNS in different protein fractions, we performed a Western-blot using an anti-GALNS antibody, produced against the N-terminal region of the enzyme16. As expected, the antibody reacted with the high molecular mass rhGALNS polypeptide (~60 kDa) but it did not detect the small rhGALNS subunit (~18 kDa) (Fig. 1E). Although the sequence encoding for the GST tag was present in the recombinant plasmids and in-frame with GALNS sequence (see plasmids maps in the Supplementary Data), the expected 26 kDa size shift corresponding to this tag was not observed. In this sense, these results might suggest that either the fusion protein GST-rhGALNS was not produced or a post-translational processing of the recombinant enzyme might eliminate the GST tag. The absence of the fusion protein was validated using an affinity chromatography (see Supplementary Data). The results showed that GST tag was produced but it was not fused to recombinant enzyme. Although, further experiments are necessary to elucidate the reasons of the production of a protein lacking the GST tag, the Western-blot analysis, in addition to the enzyme activity results, confirm the production of the rhGALNS in E. coli BL21(DE3). Furthermore, the Western-blot analysis showed a lower rhGALNS production in all the protein fractions studied by using the proU mod promoter, opposite to the production under the tac promoter (Fig. 1E). In addition, the ∼60 kDa rhGALNS precursor was observed in extra and intracellular fractions, while the precursor and the processed polypeptides were observed in the protein aggregates. These results might suggest an improvement in protein folding, since rhGALNS activity increases using the promoter proU mod even when the corresponding enzyme amounts decrease. A densitometry analysis of the Western-blot for Fig. 1E was performed using the software ImageJ24 and allowed us to roughly estimate increments in protein folding of approximately 20X and 15X in the intracellular and extracellular fractions, respectively.

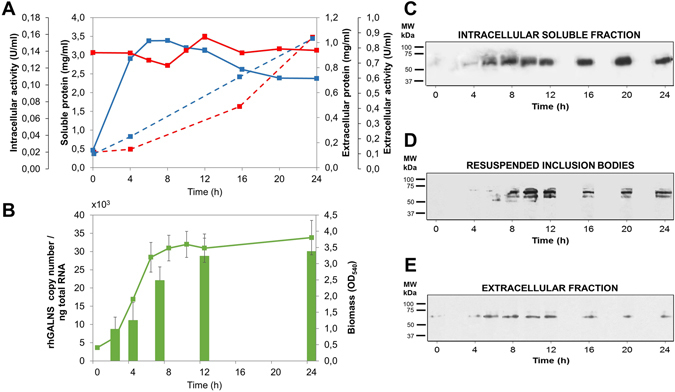

The dynamics of rhGALNS expression under the promoter proU mod was determined as shown in Fig. 2. Different parameters were monitored in 100 ml culture during the first 24 h of cultivation including the intracellular and extracellular total soluble protein, the intracellular and extracellular rhGALNS activity, amounts of rhGALNS mRNA, and the protein amount of rhGALNS in the different protein fractions. After the first 6 h of cultivation the cells decelerate their growth, entering in stationary phase, as evidenced in the steady amounts of intracellular soluble protein (Fig. 2). At this point, the expression of rhGALNS increased significantly, supported by the elevation of the rhGALNS transcripts. The expression profile is an expected gene expression dynamics profile of promoters governed by σ s regulation, as demonstrated in the study of rpoS-dependent gene promoters expressing the gene lacZ 22 and the study of stationary-phase promoters using GFP25. This increment in rhGALNS transcription leads to an increase in the corresponding protein levels, as seen in the Western-blot (it increased in an accelerated manner in the first few hours after entering stationary phase), and consequently an increment in the rhGALNS activity. An increasing concentration of rhGALNS in the solubilized protein aggregates was observed, indicating that reduced expression is not sufficient to ensure proper protein folding (Fig. 2). Analysis of the extracellular fraction exhibits a small variation of protein along with an increasing activity of rhGALNS, suggesting a higher level of protein folding. However, these findings are currently under further study. Additionally, even after the reduction of rhGALNS gene expression under the control of proU mod, we still observed a different expression pattern in protein aggregates (Fig. 2C). This phenomenon could be due to poor protein processing or traffic saturation as shown in other studies26–28.

Figure 2.

Dynamics of the expression of rhGALNS under the control of the promoter proU mod. (A) The solid lines represent the soluble protein quantitation expressed as mg/mL. Dashed lines indicate volumetric enzymatic activities expressed as U/mL. Blue lines show soluble proteins and enzyme activity of the intracellular fraction, whereas red lines are for the samples analyzed at the culture medium. These samples were analyzed at 0, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 20 and 24 hours. (B) The green solid line shows the biomass measured as OD540 at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 24 hours. Green bars represent the rhGALNS copy number per ng of total RNA, isolated at 2, 4, 7, 12 and 24 hours after inoculation. The expression profile of the promoter proU mod shown corresponds to the profile expected of promoters regulated under σ s. Western-blot analyses of rhGALNS at the, (C) Intracellular soluble fraction, (D) Solubilized protein aggregates fraction and (E) Extracellular fraction. All samples were collected at the same timestamps analyzed in part (A) Samples from the intracellular fraction were normalized by the total protein amount, solubilized protein aggregates fractions were normalized by biomass, and the extracellular samples were normalized by culture volume. A non-cropped version of this figure can be found in the Supplementary Data.

These results demonstrate the importance of controlling gene expression in the production of rhGALNS, not only in terms of promoter strength, but also regarding transcriptional dynamics and regulation. These results also support the versatility of using physiologically-controlled promoters for protein expression in the sense that it will facilitate the controllability of production processes and reduce the process costs since no inducer is required.

Induction of osmoprotectants

Two strategies to improve the amount of soluble recombinant proteins were used in this study, which involve increasing the concentration of osmolytes and the overexpression of chaperones14, 29. Overproduction of bacterial chaperones, some of which actively drive folding processes whereas others prevent protein aggregation, can be obtained by different extracellular stresses such as heat-shock30 or osmotic shock31.

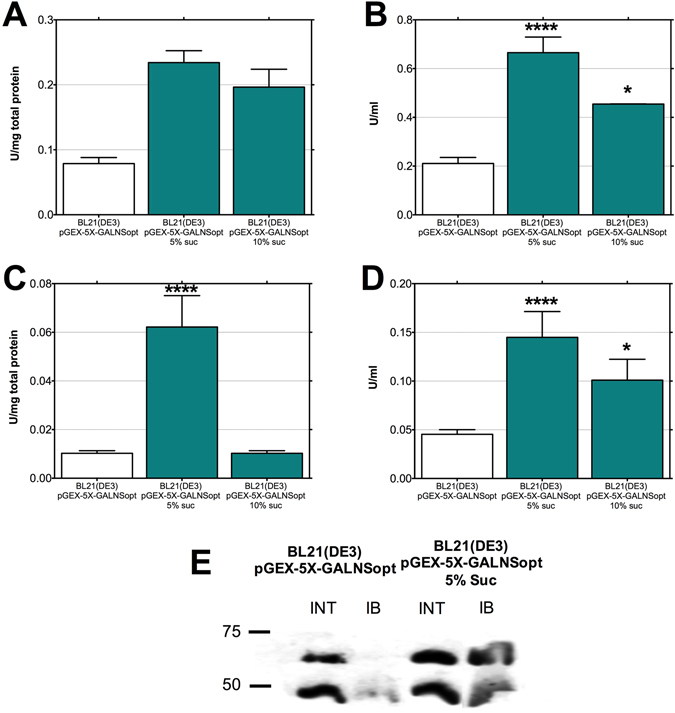

We implemented osmotic shock as a method for inducing proper protein folding, exposing the bacterial cultures of E. coli BL21(DE3)/pGEX-5X-GALNSopt to high concentrations of sucrose. Two concentrations of sucrose were tested for this purpose, 5% and 10% (w/v). As shown in Fig. 3, we observed a statistically significant increase in rhGALNS production when the two conditions were tested, although the highest response was observed using a concentration of 5% (w/v) sucrose. The lower effect observed with 10% (w/v) sucrose, in comparison with 5% (w/v) sucrose, agrees with Barth, et al.32 report, who suggested that an excessive osmotic stress in the absence of cytoplasmic compatible solutes to rescue cell grow from inhibitory conditions (e.g. organic osmolytes as betaine, carnitine, trehalose, proline, mannitol, and small peptides33), could hinder recombinant protein folding.

Figure 3.

Production of rhGALNS in E. coli BL21(DE3) with cultures exposed to high osmotic stress. (A) Specific activity in the extracellular fraction. (B) Volumetric activity in the extracellular fraction. (C) Specific activity in the intracellular fraction. (D) Volumetric activity in the intracellular fraction. Enzyme activity was assessed 24 hours after induction. A Student’s t-test was performed to assess significance, where (*) corresponds to a p-value < 0.05 and (****) p-value < 0.0001. Specific activities are expressed as U rhGALNS/(mg total protein) and volumetric activities as U/ml. (E) Western-blot of rhGALNS levels in the intracellular and insoluble protein fractions using high osmotic stress, with production controlled by the promoter tac using optimal (0.5 mM) IPTG concentration. The results showed a significant increase of rhGALNS protein in both, intracellular and solubilized protein aggregates fraction under tac control supplemented with 5% of sucrose. In addition, increased expression was observed in both processed and mature protein.

The largest increments in rhGALNS activity were obtained at the intracellular level, with enzyme activity levels of rhGALNS of 0.06 U/(mg total protein) and 0.14 U/ml (increments of 507% and 219%, respectively, in comparison to an unexposed culture) when cells were grown in presence of 5% (w/v) sucrose. This result is consistent with the effect observed in the Western-blot (Fig. 3E ). We did not observe a large increment in the amount of rhGALNS at the intracellular fraction, even if the intracellular activity increased when sucrose was added, suggesting that osmotic stress increases the proper folding of proteins at the cytoplasmic space. However, we estimated a 3-fold increment in rhGALNS recovered from the insoluble fraction, as shown in the Western-blot.

On the other hand, an interesting effect occurred with the protein secreted to the culture medium. As shown in Fig. 3A and B, although a statistically significant increment in specific activity after 24 h of induction was not observed, there was a significant increase in the volumetric activity. The same tendency was evidenced when 10% (w/v) sucrose was used. Elevated amounts of secreted rhGALNS were quantified using an indirect ELISA, as shown in Supplementary Data, where approximately 300% more rhGALNS was found in the medium when the culture was exposed to osmotic stress. In this sense, these results indicates an elevation in the amount of secreted protein but not in its folding, as well as that osmotic stress does not increase the proper folding of proteins at the periplasmic space. This effect can be explained since bacterial cells, under osmotic stress, accumulate small molecules known as osmolytes in the cytoplasm, acting as chemical chaperones34, 35.

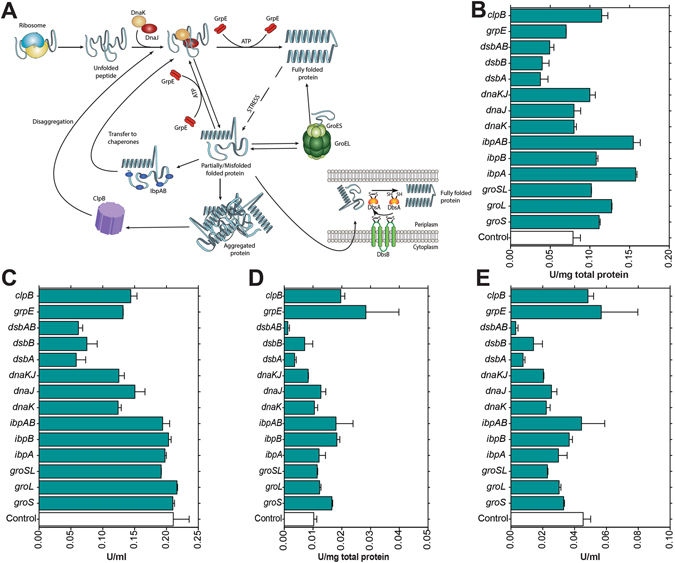

Overexpression studies were carried out to determine the effect of individual chaperones genes on the enzyme activity of rhGALNS, or on the contrary, if the observed benefit via osmotic stress was due to a global stress response. Several chaperones were selected for these overexpression studies including the chaperonin system GroESL (genes groS and groL)36; the chaperones DnaK, DnaJ and GrpE capable of repairing heat-inducing protein damage37. heat-shock proteins IbpA and IbpB involved in the binding of protein aggregates in E. coli 38; the complex DsbA-DsbB involved in the formation of disulfide bonds in the periplasmic space39 and the chaperone ClpB40. The role of these chaperones on protein folding is schematize in Fig. 4A. The plasmids for the overexpression of the chaperones proteins are summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Data. The E. coli strain BL21(DE3) was co-transformed with the plasmids pGEX-5X-GALNSopt and a recombinant pACYCDuet™-1 plasmid for overexpression of the different chaperone genes (Table 1). The clones were screened based on the double antibiotic selection and tested for rhGALNS production in 100 mL as described in the Materials and Methods section. We did not observe a benefit neither in specific nor in volumetric rhGALNS activity when the chaperones were co-expressed alongside rhGALNS (Fig. 4). Even though chaperones are cataloged as folding modulators in the production of recombinant proteins41, 42, their co-production has been shown to reduce the yield and quality of several recombinant proteins produced in E. coli, as observed in the production of horseradish peroxidase43, guinea pig liver transglutaminase44, fibroblast growth factor45, cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase46 and different antibodies fragments47, 48. In addition, overexpression of chaperones can contribute to metabolic burden, thereby leading to growth rate reduction as well as decreased final biomass yields49. It remains to be determined what genes are involved in the increment of rhGALNS activity once the cells are exposed to high concentrations of sucrose, but we hypothesize based on the findings described above, that this is the effect of a global stress response and not to the action of individual chaperones.

Figure 4.

Production of rhGALNS in E. coli BL21(DE3) when different chaperones were co-expressed. (A) The biological role of the overexpressed chaperones in protein folding in E. coli. The scheme shows the importance of the different chaperones in proper folding of nascent peptides, recovery from partially/misfolded proteins and the response to stress. (B) Specific activity in the extracellular fraction. (C) Volumetric activity in the extracellular fraction. (D) Specific activity in the intracellular fraction. (E) Volumetric activity in the intracellular fraction. Enzyme activity was assessed 24 hours after induction using optimal (0.5 mM) IPTG concentration. A Student’s t-test was performed to assess significance, where (**) corresponds to a p-value < 0.01. Specific activities are expressed as U rhGALNS/(mg total protein) and volumetric activities as U/ml. As noticed, the overexpression of individual chaperone proteins did not aid in the increase of rhGALNS activity. The names shown in this panels B to E correspond to the overexpressed chaperones. Full names of the plasmids used can be found in Table 1.

Improving formation of disulfide bonds

The disulfide bond is the most common link between amino acids after the peptide bond50 and around 15% of human produced proteins are predicted to have disulfide bonds51. In the instance of the human GALNS, it contains three disulfide bonds per monomer, increasing its stability and activity52. The formation of disulfide bonds in all organisms are compartmentalized in the extra-cytoplasmic sections such as the endoplasmic reticulum in eukaryotes, or the periplasmic space of gram-negative bacteria, such as E. coli 53, 54. This phenomenon is due to the presence of enzymes devoted to the reduction of disulfide bonds in the cytoplasm. In E. coli, the oxidative environment in the periplasm allows the formation of disulfide bonds, crucial for the activity and stability of several proteins, promoting resistance against proteases and harsh environments50. Therefore, proteins requiring disulfide bonds for their folding and stability, such as the rhGALNS, are prone to be misfolded and not active when expressed in the cytoplasm of E. coli. We hypothesized that the lower activity of the intracellular rhGALNS, in comparison to its extracellular counterpart, could be associated with inefficient protein folding due to the reducing cytoplasmic environment. For this reason, we tested the E. coli strain SHuffle® T7. This strain is an engineered version of E. coli BL21, modified to allow the formation of stable disulfide bonded proteins within the cytoplasm55. This modification was generated by the deletion of the thioredoxin reductase (trxB) and glutathione reductase (gor) genes, the presence of the mutant peroxidase AhpC* to restore reducing power to the bacteria, and the overexpression of the chaperone DsbC lacking the signal sequence to be co-expressed in the cytoplasm55.

We transformed the E. coli strain SHuffle® T7 either with the plasmids pGEX-5X-GALNSopt or pGEXproUmod. As observed in Fig. 5A and B, there were not statistically significant differences in the extracellular specific and volumetric activities of rhGALNS in E. coli strain SHuffle® T7 when the gene expression was controlled by the tac promoter, in comparison to the results observed in E. coli BL21(DE3). When the promoter proU mod was used, the outcome was similar to the previously described in regard of the specific activity, but we observed a reduced volumetric activity of rhGALNS. This effect can be attributed to the lower biomass reached by the strain E. coli SHuffle® T7 (1.8 g/L) than the one obtained using E. coli BL21(DE3) (3.2 g/L), which could be associated with the numerous genetic modifications in the strain E. coli SHuffle® T7. Nevertheless, by using the proU mod promoter, a large improvement occurred at the cytoplasm with an increase of the specific activity of 1,283% [0.14 U/(mg total protein)] (Fig. 5C and D). We evaluated the increments of protein folding by using a Western-blot (Fig. 5E). The Western-blot analysis indicates a reduction of the intracellular levels of the precursor rhGALNS using E. coli SHuffle® T7, in comparison with the levels observed by using E. coli BL21(DE3). Through a densitometric analysis of the Western-blot results, we estimated the concentrations of rhGALNS present in the evaluated samples, in order to assess the specific enzyme activity (U rhGALNS/mg rhGALNS), thus determining an approximate increment in enzyme activity of 7X at the intracellular fraction when either plasmids (pGEX-5X-GALNSopt or pGEXproUmod) were used in conjunction to the strain E. coli SHuffle® T7. However, we did not observe important variations at the extracellular fraction. This result is in accordance with the expected effect using E. coli SHuffle® T7, since all the genetic modifications in this strain are designed to improve intracellular protein folding due to an oxidative cytoplasmic conditions, but not at the periplasmic space where the disulfide forming environment is already present. Similar results were reported in the production of human herpesvirus type-6, with production increments up to 5-fold in comparison to the control strain E. coli BL21(DE3)56 and the production of the neurosecretory protein GM, with presence of intracellular soluble protein in contrast to the E. coli BL2157.

Figure 5.

Production of rhGALNS using the promoters tac and proU mod, with two different E. coli strains: BL21(DE3) and SHuffle® T7. (A) Specific activity in the extracellular fraction. (B) Volumetric activity in the extracellular fraction. (C) Specific activity in the intracellular fraction. (D) Volumetric activity in the intracellular fraction. Enzyme activity was assessed 24 hours after induction (no induction was necessary in the case of the promoter proU mod). A Student’s t-test was performed to assess significance, where (*) corresponds to a p-value < 0.05, (***) p-value < 0.001 and (****) p-value < 0.0001. Specific activities are expressed as U rhGALNS/(mg total protein) and volumetric activities as U/ml. (E) Western-blot of rhGALNS levels in the intracellular and extracellular fractions in the different studied conditions. All samples were normalized by the amount of total protein. Non-cropped versions of these figures can be found in the Supplementary Data.

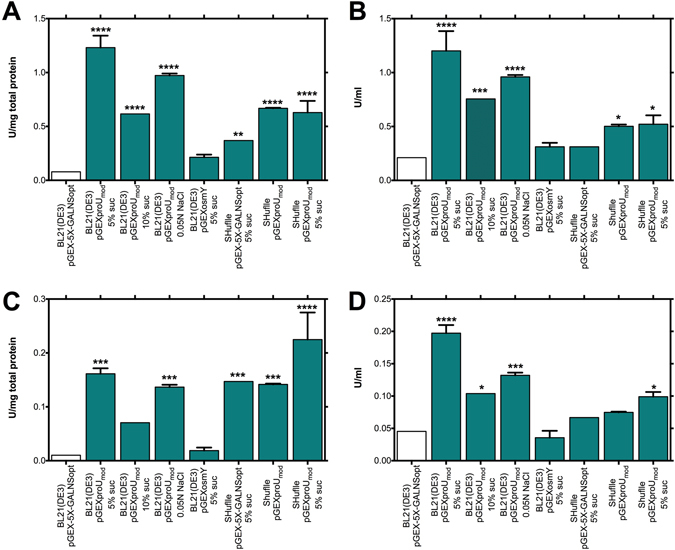

Combinatorial effect

Lastly, we tested the combination of the studied approaches to determine possible additive effects. The largest increment of rhGALNS activity in the extracellular fraction occurred with the use of proU mod promoter and 5% (w/v) sucrose, obtaining activities of 1.23 U/(mg total protein) and 1.20 U/ml, which represent an improvement of 1,463% and 470%, respectively, in comparison to the results obtained with E. coli BL21(DE3)/pGEX-5X-GALNSopt. These substantial improvements also occurred at the intracellular level as seen in Fig. 6 and Table 2, with activities of 0.16 U/(mg total protein) and 0.20 U/ml, which represent an increments of 1,475% and 335%, respectively in comparison to BL21(DE3)/pGEX-5X-GALNSopt.

Figure 6.

Production of rhGALNS in E. coli using the combinations of the different studied approaches. (A) Specific activity in the extracellular fraction. (B) Volumetric activity in the extracellular fraction. (C) Specific activity in the intracellular fraction. (D) Volumetric activity in the intracellular fraction. Enzyme activity was assessed 24 hours after induction (no induction was necessary in the case of the promoter proU mod). A Student’s t-test was performed to assess significance, where (*) corresponds to a p-value < 0.05, (**) p-value < 0.01, (***) p-value < 0.001 and (****) p-value < 0.0001. Specific activities are expressed as U rhGALNS/(mg total protein) and volumetric activities as U/ml.

Table 2.

Summary of the enzymatic rhGALNS activities obtained in this work after 24 hours of induction.

| Studied strains | Extracellular | Intracellular | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U/mg total protein (% of improvement) | U/ml (% of improvement) | U/mg total protein (% of improvement) | U/ml (% of improvement) | |

| BL21(DE3)/pGEX-5X-GALNSopt | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.04 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.05 ± 0.01 |

| BL21(DE3)/pGEX-5X-GALNSopt 5% suc | 0.23 ± 0.03 (197%) | 0.67 ± 0.09 (216%) | 0.06 ± 0.02 (507%) | 0.14 ± 0.04 (219%) |

| BL21(DE3)/pGEX-5X-GALNSopt 10% suc | 0.20 ± 0.04 (149%) | 0.45 ± 0.00 (116%) | 0.01 ± 0.00 (0%) | 0.10 ± 0.03 (122%) |

| BL21(DE3)/pGEXproUmod | 0.67 ± 0.03 (751%) | 0.86 ± 0.04 (309%) | 0.08 ± 0.00 (695%) | 0.16 ± 0.01 (245%) |

| BL21(DE3)/pGEXproUmod 5% suc | 1.23 ± 0.16 (1,463%) | 1.20 ± 0.26 (470%) | 0.16 ± 0.01 (1,475%) | 0.20 ± 0.02 (335%) |

| BL21(DE3)/pGEXproUmod 10% suc | 0.62 ± 0.07 (682%) | 0.76 ± 0.09 (259%) | 0.07 ± 0.00 (589%) | 0.10 ± 0.00 (129%) |

| BL21(DE3)/pGEXproUmod 0.05 N NaCl | 0.97 ± 0.03 (1,134%) | 0.96 ± 0.03 (355%) | 0.14 ± 0.01 (1,234%) | 0.13 ± 0.01 (191%) |

| BL21(DE3)/pGEXosmY | 0.20 ± 0.04 (156%) | 0.34 ± 0.07 (63%) | 0.02 ± 0.00 (52%) | 0.05 ± 0.01 (8%) |

| BL21(DE3)/pGEXosmY 5% suc | 0.21 ± 0.04 (171%) | 0.31 ± 0.05 (48%) | 0.02 ± 0.01 (84%) | 0.04 ± 0.02 (−22%) |

| SHuffle/pGEX-5X-GALNSopt | 0.29 ± 0.03 (274%) | 0.23 ± 0.00 (7%) | 0.06 ± 0.01 (527%) | 0.04 ± 0.01 (−19%) |

| SHuffle/pGEXproUmod | 0.67 ± 0.01 (748%) | 0.50 ± 0.02 (138%) | 0.14 ± 0.00 (1,283%) | 0.07 ± 0.00 (65%) |

| SHuffle/pGEX-5X-GALNSopt 5% suc | 0.37 ± 0.04 (369%) | 0.31 ± 0.06 (48%) | 0.15 ± 0.02 (1,336%) | 0.07 ± 0.01 (47%) |

| SHuffle/pGEXproUmod 5% suc | 0.63 ± 0.15 (698%) | 0.52 ± 0.12 (147%) | 0.22 ± 0.07 (2,095%) | 0.10 ± 0.01 (118%) |

Values in bold correspond to statistically significant improvements using a t-student test with a p-value < 0.05.

We tested if the use of a different osmotic agent, in a similar osmolarity as implemented with sucrose, leads to the same effect on rhGALNS activities. As seen in Fig. 6, using sodium chloride at 0.05 N, in conjunction with the use of the promoter proU mod, allows the production of similar enzymatic activities to the observed using sucrose in combination to the same promoter. This result suggests that the osmotic effect on rhGALNS activity is not due to the nature of the osmoreagent. Aspedon et al., using a transcriptomic analysis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa under osmotic stress with sodium chloride and sucrose indicated that stress response to osmotic shock is not dependent of a specific compound or its ionic nature, but it is rather a general stress response process58.

Finally, we observed that the highest intracellular specific activity was obtained by combining all the approaches studied in this work (i.e., 5% (w/v) of sucrose, the strain E. coli SHuffle® T7 and the promoter proU mod). This improvement corresponds to 2,095% of the activity observed under the initial culture conditions [0.22 U/(mg total protein)]. This arrangement permitted statistically significant improvements of the other studied variables, but it was not as high as with other combinations.

Conclusions

In summary, several approaches were used to increase the production of the human recombinant enzyme GALNS produced in E. coli. These approaches included the control of rhGALNS expression using a promoter regulated under σ s, the induction of osmoprotectans production through osmotic shock by using sucrose or sodium chloride, the improvement in the formation of disulfide bonds in the cytoplasmic space, and the combination of different angles to explore additive effects. The use of the promoter proU mod permitted an improvement in protein folding, with estimated increments of rhGALNS specific activities of 20X and 15X in the intracellular and extracellular fractions, respectively. This improvement could be attributed to the reduction of gene expression, as evidenced in Fig. 1E, permitting the protein folding machinery of the bacteria to cope with the folding of the recombinant protein. The nature of proU mod eliminates the use of inducers, due to the regulation of the promoter by the sigma factor σ s, thus facilitating the protein production bioprocess. We also utilized 5% (w/v) sucrose to expose bacterial cultures to osmotic shock, favoring a proper protein folding. We found important improvements at the intracellular level (Table 2), possibly due to a global stress response. This hypothesis was supported when several chaperones were co-expressed alongside rhGALNS. In this instance, none of the tested chaperones increased the rhGALNS activity, which agrees with the idea that the increase in the rhGALNS activity after osmotic shock induction was probably due to a general stress response and not to the action of a particular chaperone protein. On the other hand, as an approximation to increase proper folding of the recombinant protein by boosting the formation of disulfide bonds, we used the strain E. coli SHuffle® T7 as a host for protein production. We observed important improvements in protein activity in the intracellular fraction when rhGALNS was driven by either the promoter tac or proU mod. However, the low biomass yield hinders the use of this strain in the production of large amounts of rhGALNS. Lastly, we reported that high concentrations of sucrose in conjunction with the physiological regulated promoter proU mod significantly increased the rhGALNS production and activity. Taken together, these results represent valuable information for the production of human lysosomal enzymes in E. coli, and could have a significant impact on the development of enzyme replacement therapies for lysosomal storage diseases.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids construction

The E. coli strains, BL21(DE3) (B F- ompT gl dcm lon hsdSB (rB − mB −) λ (DE3[lacI lacUV5-T7 gene1 ind1 sam7 nin5]) [malB +] K-12 (λS)) and SHuffle® T7 (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) (F- lac pro laclQ|Δ(ara-leu)7697 araD139 fhuA2 lacZ::T7 gene1 Δ(phoA)PvuII phoR ahpC* galE (or U) galK λatt::pNEB3-r1-cDsbC (SpecR, lacIq) ΔtrxB rpsL150(StrR) Δgor Δ(malF)3) were used in this study.

Previously, we showed that recombinant GALNS produced in E. coli BL21(DE3) had a lower enzyme activity in the crude extract (i.e. production) than that reported using CHO cells9. In an attempt to increase the enzyme production, GALNS cDNA sequence (GenBank accession number NM_000512.4) was optimized by adapting the codon usage to the bias of E. coli, as well as by removing any negative cis-acting sites (i.e. splice sites, TATA-boxes, etc.). Optimized GALNS cDNA (GALNSopt) was synthesized by InvitrogenTM GeneArt® (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The synthetic gene was inserted between the EcoRI and XhoI sites of pGEX-5X-3 (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) to generate pGEX-5X-GALNSopt plasmid (6.4 kb) where rhGALNS expression is driven by the tac promoter. This plasmid was used as control of rhGALNS expression in most of the experiments carried out in this study.

The pGEX-5X-GALNSopt plasmid was used as backbone for the expression of rhGALNS under the control of the physiologically regulated promoters proU CCTATAAT (5′-GGG GCC GCC TCA GAT TCT CAG TAT GTT ATA ATA GAA AA-3′)22 and osmY (5′-TAT CCC GAG CGG TTT CAA AAT TGT GAT CTA TAT TTA ACA AA-3′)23. The ribosomal binding sites were designed to maximize the translational initiation rates, using the RBS Calculator from Salis Lab59. The RBS designed for the promoters osmY and proU mod (proU CCTATAAT) were 5′-CGA AAT CAA CAA AAG CGG TTA CTA AC-3′ and 5′-GCG AAC GGA AAT CTA CGG TTA ACA T-3′, respectively. All primers used in this study are summarized in Table 3. For the construction of the plasmid pGEXosmY, the backbone was amplified via PCR with high-fidelity Bestaq™ DNA Polymerase (Applied Biological Materials, Richmond, BC, Canada), using the primers pGEX-5X-f and osmY-r and the rhGALNS gene was amplified using the primers osmY-f and pGEX-5X-r. For the generation of these amplicons, the plasmid pGEX-5X-GALNSopt was used as template for PCR. The “scarless” cloning technique, Sequence and Ligation Independent Cloning (SLIC)60 was used to create the DNA assembles RBS/promoter/backbone. In short, equimolar amounts of the amplicons (total 200 ng) were mixed with 1 µL of 1/5 diluted (in water) 100X bovine serum albumin (New England Biolabs) and 1 µL 1/5 diluted T4 DNA Polymerase [1 uL NEBuffer2, 7 uL H20, 2 µL T4-Polymerase (3 U/ml) (New England Biolabs)]. The total reaction volume was 20 µL. The mixture was incubated at 22 °C for 5 min, heated up to 70 °C for 20 minutes, followed by 30 minutes at 37 °C using a 10% ramp, and then kept at 4 °C for 18 hours. The reaction product was transformed via electroporation into E. coli DH5α and grown onto solid LB agar supplemented with 100 ng/µL of ampicillin. Transformants were screened with restriction endonucleases and the correct construct was transformed in E. coli BL21(DE3) using heat shock. A similar protocol was implemented for the construction of the plasmid pGEXproUmod, where the primers pGEX-5X-f and proU-r, and proU-f and pGEX-5X-r were used to obtain the amplicons corresponding to the backbone and rhGALNS, assembled together using SLIC as previously described.

Table 3.

Primers used in this study.

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| pGEX-5X-f | 5′-CCT ATT TTT ATA GGT TAA TGT CAT GAT AAT AAT GGT TTC TTA GAC GTC-3′ |

| pGEX-5X-r | 5′-CAT TAA CCT ATA AAA ATA GGC GTA TCA CGA GGC CCT TTC -3′ |

| osmY-f | 5′-TCT ATA TTT AAC AAA CGA AAT CAA CAA AAG CGG TTA CTA ACA TGT CCC CTA TAC TAG GTT ATT G-3′ |

| osmY-r | 5′-TTT CGT TTG TTA AAT ATA GAT CAC AAT TTT GAA ACC GCT CGG GAT AGG AAT TTA TGC GGT GTG AAA TAC -3′ |

| proU-f | 5′-ATT CTC AGT ATG TTA TAA TAG AAA AGC GAA CGG AAA TCT ACG GTT AAC ATA TGT CCC CTA TAC TAG GTT ATT G-3′ |

| proU-r | 5′-ATT TCC GTT CGC TTT TCT ATT ATA ACA TAC TGA GAA TCT GAG GCG GCC CCG GAA TTT ATG CGG TGT GAA ATA C-3′ |

| groS-f | 5′-ATC CGA ATT CAT GAA TAT TCG TCC ATT GCA TGA T-3′ |

| groS-r | 5′-CGC AAG CTT TTA CGC TTC AAC AAT TGC CAG-3′ |

| groL-f | 5′-TAT ACA TAT GAT GGC AGC TAA AGA CGT AA-3′ |

| groL-r | 5′-CAG ACT CGA GTT ACA TCA TGC CGC CCA TG-3′ |

| dnaK-f | 5′-ATT CGA GCT CAT GGG TAA AAT AAT TGG TAT CGA C-3′ |

| dnaK-r | 5′-CCG CAA GCT TTT ATT TTT TGT CTT TGA CTT CTT CAA ATT C-3′ |

| dnaJ-f | 5′-TAT ACA TAT GAT GGC TAA GCA AGA TTA TTA CGA G-3′ |

| dnaJ-r | 5′-CAG ACT CGA GTT AGC GGG TCA GGT CGT C-3′ |

| dsbA-f | 5′-ATC CGA ATT CAT GAA AAA GAT TTG GCT GGC G-3′ |

| dsbA-r | 5′-CCG CAA GCT TTT ATT TTT TCT CGG ACA GAT ATT TCA CT-3′ |

| dsbB-f | 5′-TAT ACA TAT GAT GTT GCG ATT TTT GAA CCA ATG-3′ |

| dsbB-r | 5′-CAG ACT CGA GTT AGC GAC CGA ACA GAT CAC G-3′ |

| ibpA-f | 5′-ATC CGA ATT CAT GCG TAA CTT TGA TTT ATC CCC-3′ |

| ibpA-r | 5′-CCG CAA GCT TTT AGT TGA TTT CGA TAC GGC GC-3′ |

| ibpB-f | 5′-TAT ACA TAT GAT GCG TAA CTT CGA TTT ATC CCC-3′ |

| ibpB-r | 5′-AGA CTC GAG TTA GCT ATT TAA CGC GGG ACG T-3′ |

| grpE-f | 5′-ATC CGA ATT CAT GAG TAG TAA AGA ACA GAA AAC G-3′ |

| grpE-r | 5′-ATG CGG CCG CTT AAG CTT TTG CTT TCG CTA CAG-3′ |

| clpB-f | 5′-TAT ACA TAT GAT GCG TCT GGA TCG TCT TAC-3′ |

| clpB-r | 5′-CAG ACT CGA GTT ACT GGA CGG CGA CAA TC-3′ |

| GALNS -f | 5′-GTG AAC CGA GCC GTG AAA CC-3′ |

| GALNS-r | 5′-ACC AAT GCA CAT GCA CGC AA-3′ |

All the corresponding genes for the chaperones in study were amplified via PCR from genomic DNA of E. coli BL21(DE3) using the high-fidelity Bestaq™ DNA Polymerase (Applied Biological Materials) and cloned into the bicistronic plasmid pACYCDuet™-1 (Novagen, Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) by restriction digest. All the constructs are summarized in Table 1 and their respective maps in Supplementary Data. For the co-expression of the chaperone protein and rhGALNS, the corresponding plasmid was transformed using heat-shock into the strain E. coli BL21(DE3)/pGEX-5X-GALNSopt and screened using double antibiotic selection (AmpR + CmR).

Culture conditions

Overnight cultures were grown in LB liquid medium or on solid LB agar plates supplemented with appropriated antibiotics and incubated at 37 °C. Production of rhGALNS was carried out in 100 mL cultures using M9 minimum medium [2 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 6.78 g/L Na2HPO4, 3 g/L KH2PO, 4.5 g/L NaCl, 1 g/L NH4Cl, 1 mg/L thiamine and trace elements. 1000X trace elements solution: 13.4 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), 3.1 mM FeCl3.6H2O, 0.62 mM ZnCl2, 76 µM CuCl2.2H2O, 42 µM CoCl2.2H2O, 162 µM H3BO3, 8.1 µM MnCl2.4H2O, 36.3 mg/L AlCl, 2.9 mg/L NiCl2·6H2O] supplemented with 20 g/L of D-glucose under aerobic conditions, using appropriated antibiotics. When necessary, gene expression was induced using isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, Gold Biotechnology, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 0.5 mM after 8 hours of incubation. All cultures were maintained at 180 RPM during cultivation. Cells were cultivated for 24 hours after induction. Biomass was estimated using optical density at 540 nm. To evaluate the effect of osmotic stress on protein production and activity, sucrose was added to the cultures at 5% and 10% (w/v) or sodium chloride to a concentration of 0.5 mM. All assays were done in triplicate.

Crude protein assays

Fifty mL cultures were centrifuged and the growth media was saved for further analysis. The pellets were resuspended in 5 mL lysis buffer (25 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5% (v/v) glycerol, and 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, to a pH 7.2). Samples were sonicated during 1 minute at 4 °C and 25% amplitude (Vibra-Cell, Sonics & Materials Inc., Newtown, CT, USA) and centrifuged at 3000 × g and 4 °C during 20 minutes9, 61. The soluble fraction (supernatant) was stored at −20 °C for further analysis. Recovered pellets were processed for analysis of the insoluble fraction. The protein aggregates were solubilized by mixing 2 µL of lysed cells in 30 µL of 6X SDS loading buffer (375 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 6% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 48% glycerol, 9% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.03% bromophenol blue) and boiled at 95 °C for 10 min.

Quantification of GALNS activity

rhGALNS activity was assessed using the fluorescent substrate 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-D-galactopyranoside-6-sulfate (Toronto Chemicals Research, North York, ON, Canada) as described elsewhere62. One unit (U) was defined as the amount of rhGALNS catalyzing 1 nmol substrate per hour, and rhGALNS activity was expressed as U/(mg total protein) (total protein determined by Lowry protein assay63) or as U/mL. Enzyme activity was assayed in the soluble fraction (intracellular) and growth media (extracellular).

SDS–PAGE Analysis

Crude proteins extracts and growth media were analyzed by SDS - polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) under reducing conditions as described by Laemmli et al.64. SDS-PAGE was carried out using 12% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels and 3% (w/v) polyacrylamide stacking gel. The molecular masses were estimated using the protein ladder Precision Plus Protein™ (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). The gels were stained with Coomassie blue R-250 (BioRad).

Western blotting

The proteins from different fractions were homogenized in lysis buffer and equivalent amounts of total protein extracts were loaded and processed by SDS-PAGE gels and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Amershan ProtanTM 0.45 µm, GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). The membranes were blocked with a blocking buffer containing TTBS [0.3% Tween 20, and 5% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)] at room temperature for 1 hour. Membranes containing resuspended protein aggregates, extracellular and intracellular proteins were incubated overnight at 4 °C with a specific primary antibody rabbit anti human GALNS (1:1000 in blocking buffer)9. The specificity of this antibody was previously assessed, and no band was recognized in samples from non-induced and plasmid-free strains9. A peroxidase conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Sigma-Aldrich) was added (1:2000 in blocking buffer) for 1 hour at room temperature. The specific bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (SuperSignal™ West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate, Thermo Fisher Scientific®, Waltham, MA, USA).

qRT-PCR experiments

Frozen stocks of the strain BL21(DE3)/pGEXproUmod (0.5 mL) were transferred into 10 mL of fresh LB media supplemented with 100 ng/mL of ampicillin and incubated for 18 h at 37 °C and 180 rpm. Production of rhGALNS was carried out in 100 mL cultures using M9 minimum medium supplemented with 20 g/L of D-glucose under aerobic conditions, inoculated with 10 mL of overnight culture, kept at 37 °C and 180 rpm. Samples (10 mL) were taken 2, 4, 7, 12 and 24 hours after inoculation of all three biological replicas. The samples were pelleted by centrifugation at 3000 x g and 4 °C during 10 minutes. The supernatant was discarded and the pellets were immediately placed at −80 °C until further processing. The samples were processed in a period lower than 12 hours after pelleting. Total RNA was extracted using the ZR Fungal/Bacterial RNA MiniprepTM Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA), following manufacturer’s indications and immediately stored at −80 °C. The cDNA was generated using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using 100 ng of total RNA and following the random hexamer primed synthesis manufacturer’s protocol. Two primers (GALNS-f and GALNS-r) (Table 3)) were designed for the quantification of rhGALNS transcripts using NCBI Primer Design Tool and they were used for the qPCR experiments. Primer amplification efficiency was assessed using the plasmid pGEXproUmod (purified using the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-up System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA)) as template. The amplification efficiency of these primers was estimated as 94%. To generate a standard curve for absolute rhGALNS copy number quantification, the plasmid pGEXproUmod was serially diluted to obtain different plasmid copies ranging from 300,000 to 30. Triplicates of each data-point were used to ensure reliability of the data. All qPCR experiments were carried out using Luna® Universal qPCR Master Mix (New England Biolabs) following manufacturer’s indications and read in a QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The results as reported as rhGALNS copy number per ng of total RNA.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was evaluated using a Student’s t-test, employing the software GraphPad Prism version 6 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Juan David Patiño Salazar for the help in the qRT-PCR experiments and Oscar Alejandro Hidalgo Lanussa with his assistance with the creation of the illustrations. LHR and CC were supported by Pontificia Universidad Javeriana and COLCIENCIAS [Grant No. FP44842-232-2015, ID 6700 (Mejoramiento en la producción de proteínas recombinantes mediante el uso de biología sintética e ingeniería de proteínas) and FP44842-233-2015, ID 6699]. ARL received a doctoral scholarship from Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. CJAD was also supported by Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (Grant ID 3964, 5537, and 7204) and COLCIENCIAS (Grant ID 5174, contract No. 120356933205; and Grant ID 5170, contract No. 120356933427).

Author Contributions

L.H.R. and C.J.A.-D. designed the research; L.H.R., C.C. and L.N.P. performed the experiments; L.H.R., C.C., A.R.-L. and C.J.A.-D. analyzed the data; L.H.R., C.C., A.R.-L. and C.J.A.-D. wrote the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-06367-w

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Luis H. Reyes, Email: lh.reyes@uniandes.edu.co

Carlos J. Alméciga-Díaz, Email: cjalmeciga@javeriana.edu.co

References

- 1.Montano AM, Tomatsu S, Gottesman GS, Smith M, Orii T. International Morquio A Registry: clinical manifestation and natural course of Morquio A disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30:165–174. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0529-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomatsu, S. et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis type IVA (Morquio A disease): clinical review and current treatment. Curr Pharm Biotechnol12, 931–945, doi:1389-2010/11 $58.00+0.00 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Tomatsu S, et al. Morquio A syndrome: diagnosis and current and future therapies. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2014;12(Suppl 1):141–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendriksz CJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of enzyme replacement therapy with BMN 110 (elosulfase alfa) for Morquio A syndrome (mucopolysaccharidosis IVA): a phase 3 randomised placebo-controlled study. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10545-014-9715-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomatsu S, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy for treating mucopolysaccharidosis type IVA (Morquio A syndrome): effect and limitations. Expert Opinion on Orphan Drugs. 2015;3:1279–1290. doi: 10.1517/21678707.2015.1086640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomatsu S, et al. Enhancement of drug delivery: enzyme-replacement therapy for murine Morquio A syndrome. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1094–1102. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Espejo-Mojica Á, et al. Human recombinant lysosomal enzymes produced in microorganisms. Mol Genet Metab. 2015;116:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bielicki J, et al. Expression, purification and characterization of recombinant human N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulphatase. Biochem J. 1995;311(Pt 1):333–339. doi: 10.1042/bj3110333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez A, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy for Morquio A: an active recombinant N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate sulfatase produced in Escherichia coli BL21. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;37:1193–1201. doi: 10.1007/s10295-010-0766-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodríguez-López, A. et al. Recombinant human N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate sulfatase (GALNS) produced in the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris. Sci Rep6, 29329, doi:10.1038/srep29329http://www.nature.com/articles/srep29329-supplementary-information (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Kamionka M. Engineering of therapeutic proteins production in Escherichia coli. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2011;12:268–274. doi: 10.2174/138920111794295693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Critchley RJ, et al. Potential therapeutic applications of recombinant, invasive E. coli. Gene Ther. 2004;11:1224–1233. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baeshen MN, et al. Production of Biopharmaceuticals in E. coli: Current Scenario and Future Perspectives. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;25:953–962. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1412.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baneyx F, Mujacic M. Recombinant protein folding and misfolding in Escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1399–1408. doi: 10.1038/nbt1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mosquera A, et al. Characterization of a recombinant N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate sulfatase produced in E. coli for enzyme replacement therapy of Morquio A disease. Process Biochem. 2012;47:2097–2102. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2012.07.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernandez A, et al. Effect of culture conditions and signal peptide on production of human recombinant N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate sulfatase in Escherichia coli BL21. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;23:689–698. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1211.11044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carrio MM, Villaverde A. Construction and deconstruction of bacterial inclusion bodies. J Biotechnol. 2002;96:3–12. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(02)00032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muller-Hill B, Crapo L, Gilbert W. Mutants that make more lac repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;59:1259–1264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.59.4.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sweet CR. Expression of recombinant proteins from lac promoters. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;235:277–288. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-409-3:277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannig G, Makrides SC. Strategies for optimizing heterologous protein expression in Escherichia coli. Trends Biotechnol. 1998;16:54–60. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Boer HA, Comstock LJ, Vasser M. The tac promoter: a functional hybrid derived from the trp and lac promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:21–25. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wise A, Brems R, Ramakrishnan V, Villarejo M. Sequences in the −35 region of Escherichia coli rpoS-dependent genes promote transcription by E sigma S. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2785–2793. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2785-2793.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yim HH, Brems RL, Villarejo M. Molecular characterization of the promoter of osmY, an rpoS-dependent gene. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:100–107. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.100-107.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miksch G, et al. A rapid reporter system using GFP as a reporter protein for identification and screening of synthetic stationary-phase promoters in Escherichia coli. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2006;70:229–236. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mergulhao FJ, Taipa MA, Cabral JM, Monteiro GA. Evaluation of bottlenecks in proinsulin secretion by Escherichia coli. J Biotechnol. 2004;109:31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2003.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenberg, H. F. Isolation of recombinant secretory proteins by limited induction and quantitative harvest. Biotechniques24, 188–190, 192 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Mergulhao FJ, Summers DK, Monteiro GA. Recombinant protein secretion in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Adv. 2005;23:177–202. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kempf B, Bremer E. Uptake and synthesis of compatible solutes as microbial stress responses to high-osmolality environments. Arch Microbiol. 1998;170:319–330. doi: 10.1007/s002030050649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen J, Acton TB, Basu SK, Montelione GT, Inouye M. Enhancement of the solubility of proteins overexpressed in Escherichia coli by heat shock. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;4:519–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Marco A, Vigh L, Diamant S, Goloubinoff P. Native folding of aggregation-prone recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli by osmolytes, plasmid- or benzyl alcohol-overexpressed molecular chaperones. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2005;10:329–339. doi: 10.1379/CSC-139R.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barth S, et al. Compatible-solute-supported periplasmic expression of functional recombinant proteins under stress conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:1572–1579. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.4.1572-1579.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Csonka LN. Physiological and genetic responses of bacteria to osmotic stress. Microbiological Reviews. 1989;53:121–147. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.121-147.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Marco, A. In Protein Aggregation in Bacteria 77–92 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2014).

- 35.Kim S-H, Yan Y-B, Zhou H-M. Role of osmolytes as chemical chaperones during the refolding of aminoacylase. Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2006;84:30–38. doi: 10.1139/o05-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin J. Protein folding assisted by the GroEL/GroES chaperonin system. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1998;63:374–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schroder H, Langer T, Hartl FU, Bukau B. DnaK, DnaJ and GrpE form a cellular chaperone machinery capable of repairing heat-induced protein damage. EMBO J. 1993;12:4137–4144. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laskowska E, Wawrzynow A, Taylor A. IbpA and IbpB, the new heat-shock proteins, bind to endogenous Escherichia coli proteins aggregated intracellularly by heat shock. Biochimie. 1996;78:117–122. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)82643-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whitley P, von Heijne G. The DsbA-DsbB system affects the formation of disulfide bonds in periplasmic but not in intramembraneous protein domains. FEBS Lett. 1993;332:49–51. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80481-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barnett ME, Zolkiewska A, Zolkiewski M. Structure and activity of ClpB from Escherichia coli. Role of the amino-and -carboxyl-terminal domains. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37565–37571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005211200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Marco A. Protocol for preparing proteins with improved solubility by co-expressing with molecular chaperones in Escherichia coli. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2632–2639. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Marco A, De Marco V. Bacteria co-transformed with recombinant proteins and chaperones cloned in independent plasmids are suitable for expression tuning. J Biotechnol. 2004;109:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2003.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kondo A, et al. Improvement of productivity of active horseradish peroxidase in Escherichia coli by coexpression of Dsb proteins. J Biosci Bioeng. 2000;90:600–606. doi: 10.1016/S1389-1723(00)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ikura K, et al. Co-overexpression of folding modulators improves the solubility of the recombinant guinea pig liver transglutaminase expressed in Escherichia coli. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2002;32:189–205. doi: 10.1081/PB-120004130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rinas U, Hoffmann F, Betiku E, Estape D, Marten S. Inclusion body anatomy and functioning of chaperone-mediated in vivo inclusion body disassembly during high-level recombinant protein production in Escherichia coli. J Biotechnol. 2007;127:244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim SG, Kweon DH, Lee DH, Park YC, Seo JH. Coexpression of folding accessory proteins for production of active cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase of Bacillus macerans in recombinant Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 2005;41:426–432. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu X, et al. Optimisation of production of a domoic acid-binding scFv antibody fragment in Escherichia coli using molecular chaperones and functional immobilisation on a mesoporous silicate support. Protein Expression and Purification. 2007;52:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levy R, Weiss R, Chen G, Iverson BL, Georgiou G. Production of correctly folded Fab antibody fragment in the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli trxB gor mutants via the coexpression of molecular chaperones. Protein Expr Purif. 2001;23:338–347. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berges H, Joseph-Liauzun E, Fayet O. Combined effects of the signal sequence and the major chaperone proteins on the export of human cytokines in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:55–60. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.55-60.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fass D. Disulfide bonding in protein biophysics. Annu Rev Biophys. 2012;41:63–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-050511-102321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wong JW, Ho SY, Hogg PJ. Disulfide bond acquisition through eukaryotic protein evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:327–334. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rivera-Colon Y, Schutsky EK, Kita AZ, Garman SC. The structure of human GALNS reveals the molecular basis for mucopolysaccharidosis IV A. J Mol Biol. 2012;423:736–751. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bardwell JC, McGovern K, Beckwith J. Identification of a protein required for disulfide bond formation in vivo. Cell. 1991;67:581–589. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90532-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weissman JS, Kim PS. Efficient catalysis of disulphide bond rearrangements by protein disulphide isomerase. Nature. 1993;365:185–188. doi: 10.1038/365185a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lobstein J, et al. SHuffle, a novel Escherichia coli protein expression strain capable of correctly folding disulfide bonded proteins in its cytoplasm. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11:56. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tait AR, Straus SK. Overexpression and purification of U24 from human herpesvirus type-6 in E. coli: unconventional use of oxidizing environments with a maltose binding protein-hexahistine dual tag to enhance membrane protein yield. Microbial Cell Factories. 2011;10:51–51. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-10-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Masuda K, Furumitsu M, Taniuchi S, Iwakoshi-Ukena E, Ukena K. Production and characterization of neurosecretory protein GM using Escherichia coli and Chinese Hamster Ovary cells. FEBS Open Bio. 2015;5:844–851. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aspedon A, Palmer K, Whiteley M. Microarray Analysis of the Osmotic Stress Response in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of Bacteriology. 2006;188:2721–2725. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.7.2721-2725.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Espah Borujeni A, Channarasappa AS, Salis HM. Translation rate is controlled by coupled trade-offs between site accessibility, selective RNA unfolding and sliding at upstream standby sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:2646–2659. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li MZ, Elledge SJ. Harnessing homologous recombination in vitro to generate recombinant DNA via SLIC. Nat Methods. 2007;4:251–256. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thomas JG, Baneyx F. Protein misfolding and inclusion body formation in recombinant Escherichia coli cells overexpressing Heat-shock proteins. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11141–11147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Diggelen OP, et al. A fluorimetric enzyme assay for the diagnosis of Morquio disease type A (MPS IV A) Clin Chim Acta. 1990;187:131–139. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(90)90339-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dawson JM, Heatlie PL. Lowry method of protein quantification: evidence for photosensitivity. Anal Biochem. 1984;140:391–393. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of Structural Proteins during the Assembly of the Head of Bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.