Abstract

Aim: To investigate the association of retinal vascular changes with a risk of dementia in longitudinal population-based study.

Methods: We performed a nested case-control study of 3,718 persons, aged 40–89 years, enrolled between 1983 and 2004. Retinal vascular changes were observed in 351 cases with disabling dementia (average period before the onset, 11.2 years) and in 702 controls matched for sex, age, and baseline year. Incidence of disabling dementia was defined as individuals who received cares for disabilities including dementia-related symptoms and/or behavioral disturbance. Conditional logistic regression analysis was used to calculate odds ratio (OR) and multivariable adjusted OR (Models 1 and 2) for incidence of disabling dementia according to each retinal vascular change. Regarding confounding variables, Model 1 included overweight status, hypertension, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and smoking status, whereas Model 2 also included incidence of stroke prior to disabling dementia for further analysis.

Results: The proportion of cases (controls) with retinal vascular changes was 23.1 (15.7)% for generalized arteriolar narrowing, 7.7 (7.5)% for focal arteriolar narrowing, 15.7 (11.8)% for arteriovenous nicking, 10.5 (9.3)% for increased arteriolar wall reflex, and 11.4 (9.8)% for any other retinopathy. Generalized arteriolar narrowing was associated with an increased risk of disabling dementia: crude OR, 1.66 (95% confidence interval, 1.19–2.31); Model 1: OR, 1.58 (1.12–2.23); Model 2: OR, 1.48 (1.04–2.10). The number of retinal abnormalities was associated in a dose–response manner with the risk.

Conclusion: Generalized arteriolar narrowing and total number of retinal abnormalities may be useful markers for identifying persons at higher risks of disabling dementia.

Keywords: Retinal vascular changes, Retinopathy, Dementia, Cohort studies, Nested case-control studies

See editorial vol. 24: 675–676

Introduction

Dementia has become a major burden in disabled elderly individuals1, 2). Microvascular brain damage, such as microinfarction, microhemorrhage, and macrohemorrhage3, 4), as well as peripheral arterial stiffness5, 6), heighten the risk of cognitive impairment. Previous studies have suggested that such brain abnormalities may be associated with retinal vascular changes due to shared embryological, anatomical, and physiological features7–9). In addition, retina is the only location in which it is possible to macroscopically diagnose microvascular abnormalities. Retinal vascular changes, therefore, may serve as risk markers for dementia, but the epidemiological evidence has been limited10).

Several longitudinal population-based studies have investigated the associations between retinal vascular changes and incidence of dementia11), or indicators of dementia such as brain imaging abnormalities12–15), cognitive decline16), and disability17), but these results have been inconsistent. In addition, most of these studies investigated the association of retinal vascular changes with the risk of dementia and/or cognitive decline without taking into account incidence of stroke before the onset of dementia. Nevertheless, retinal vascular changes have been shown to be risk markers for incidence of stroke18–20). Therefore, further longitudinal population-based studies are becoming increasingly important in order to confirm these associations while also considering mediation by incidence of stroke.

Our hypothesis was that retinal vascular changes would be associated with an increased risk of disabling dementia and that this association would persist after further adjustment for incidence of stroke before the onset of disabling dementia.

Methods

Case and Control Identification

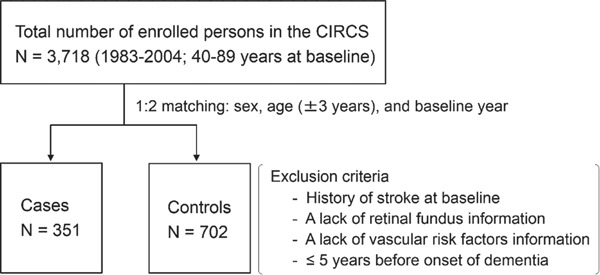

We performed a nested case-control study of 3,718 people, ranging in age from 40 to 89 years, who lived in the Ikawa community in Japan and were enrolled in the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS) between 1983 and 2004 (Fig. 1). Details of the CIRCS protocol have been described elsewhere21–23). Briefly, this cohort was followed via annual cardiovascular risk surveys and surveillance for incidence and mortality of stroke. Surveillance for disabling dementia was also conducted from October 1999 until March 2014.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the present study.

Flow diagram of participant enrollment and selection for nested case-control study.

The criteria of disabling dementia were the same as those of our previous studies21, 24–26). Incidence of disabling dementia was defined as individuals who received cares for disability including dementia-related symptoms and/or behavioral disturbance and who were ranked as II or greater on the standardized physicians' classification in Long-Term Care Insurance in Japan. These criteria were validated by comparing with neuropsychiatrists' diagnoses as defined by the International Psychogeriatric Association27), which examine five domains of cognitive function: attention, memory, visuospatial function, language, and reasoning. A total of 622 people, aged 65 years or older, were evaluated by neuropsychiatrists and 123 persons were diagnosed with disabling dementia. The calculated sensitivity and specificity values for disabling dementia were 82.9% and 95.8%, respectively26).

We identified 351 cases with disabling dementia and matched two controls with each case based on sex, age (±3 years), and baseline year. We excluded persons with a history of stroke at baseline or lack of retinal fundus information and/or vascular risk factors information. We also excluded cases that developed disabling dementia within 5 years from their baseline. The Ethics Committees of the Osaka Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Osaka University approved this study.

Retinal Vascular Changes

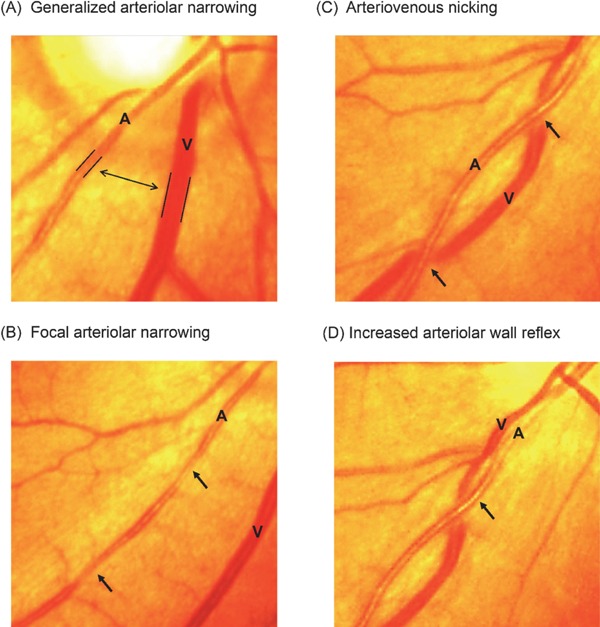

All participants underwent retinal fundus photography of their right eye using a retinal camera at least once every 2 years. When a photograph of the right eye was not obtained due to anterior segment or media opacity (e.g., corneal opacity or cataracts), a photograph of the left eye was taken; photographs of the right eye were used in 96% of participants. Two well-trained physicians and/or medical technologists evaluated retinal findings and identified the presence of generalized arteriolar narrowing, focal arteriolar narrowing, arteriovenous nicking, increased arteriolar wall reflex, and any other retinopathy. As shown in Fig. 2, we graded retinal vascular change as “present” when the following criteria were found: (A) for generalized arteriolar narrowing, an arteriolar-to-venular ratio of 2:3 or lower; (B) for focal arteriolar narrowing, localized constrictions along the course of arterioles; (C) for arteriovenous nicking, narrowing or invisibility of a vein as an arteriole crossed over it; and (D) for increased arteriolar wall reflex, the presence of an increased light reflex from the central portion of the retinal arteriolar wall surface28). The presence of other retinopathies was based on the observation of any of the following lesions: blot or flame-shaped hemorrhages, microaneurysms, exudates (soft or hard), optic disc swelling, new vessels at the disk or elsewhere, intra retinal microvascular abnormalities, vitreous hemorrhage, or laser photocoagulation scars28). Additionally, the overall impact of retinal microvascular changes was estimated based on the total number of retinal abnormalities, including generalized arteriolar narrowing, focal arteriolar narrowing, arteriovenous nicking, increased arteriolar wall reflex, and the other retinopathies. We previously calculated intergrader prevalence- and bias-adjusted Kappa scores in a preliminary validation study of 116 eyes, and the principal major results were 0.52 for generalized arteriolar narrowing, 0.48 for focal arteriolar narrowing, 0.59 for arteriovenous nicking, and 0.98 for hemorrhages.

Fig. 2.

Example photographs of retinal vascular changes.

A, retinal arteriole; V, retinal venule; Example photographs of retinal vascular changes: (A) Generalized arteriolar narrowing: arteriolar-to-venular diameter ratio of 2:3 or lower; (B) Focal arteriolar narrowing: localized constrictions along the course of arterioles; (C) Arteriovenous nicking: narrowing of a venule as an arteriole crosses over it; and (D) Increased arteriolar wall reflex: an increased light reflex from the central portion of the retinal arteriolar surface; All photographs were modified from Iida and Kitamura (2009) with the authors' permission28).

Vascular Risk Factors

We calculated body mass index as body weight (kg) divided by body height squared (m2), and overweight was defined as 25 kg/m2 or higher. Blood pressures were measured by trained physicians using standard mercury sphygmomanometers and standardized epidemiological methods. We defined hypertension as systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or higher and/or diastolic blood pressure of 90 mmHg or higher and/or antihypertensive medication use. We also identified hyperglycemia as fasting serum glucose of 110 mg/dl or higher or casual serum glucose 140 mg/dl or greater and/or antidiabetic medication use and hypercholesterolemia as serum total cholesterol of 220 mg/dl or higher and/or lipid-lowering medication use. A standard 12-lead resting electrocardiogram was obtained in supine position, and we noted atrial fibrillation (Minnesota Codes, 8-3-1 or 8-3-2) and ST-T changes (Minnesota Code, 4-1 to 4-3 and/or 5-1 to 5-3). We identified current smokers as those who reported smoking one or more cigarettes per day, past smokers as those who had quit smoking for 3 months or more, current drinkers as those who reported drinking 1 or more times per week, and ex-drinkers as those who had not drunk for 3 months or more.

Ascertainment of Incidence of Stroke

From 1981 to the present, we obtained information on incidence of stroke from death certificates, national insurance claims, annual cardiovascular risk surveys, and reports by local physicians, public health nurses, and health volunteers. To confirm the diagnoses, all living patients were telephoned, visited, or invited to participate in the risk surveys, or alternatively, a medical history was obtained from their families. In addition, medical records and findings of imaging studies such as CT and/or MRI from local clinics and hospitals were reviewed. In cases of death, histories were obtained from families and/or attending physicians and medical records were reviewed. The definition of incidence of stroke was a focal neurological disorder with rapid onset that persisted for at least 24 h or until death (International Classification of Diseases, 9 th Revision, code 430–438). Final diagnoses of stroke were made by a panel of three to four epidemiologists who were blinded to the data from the risk surveys.

Statistical Analysis

The analysis of covariance was used to test for differences in means and proportions of baseline characteristics between cases and controls. We calculated the conditional odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for incidence of disabling dementia associated with generalized arteriolar narrowing, focal arteriolar narrowing, arteriovenous nicking, increased arteriolar wall reflex, any other retinopathy, and the total number of retinal abnormalities (one, two, or more). Two models were constructed. Model 1 included adjustments for vascular risk factors: overweight status (yes, no), hypertension (yes, no), hyperglycemia (yes, no), hypercholesteremia (yes, no), electrocardiogram abnormality (yes, no), current smoking status (current, past, never), and drinking status (current, ex-, never). Model 2 incorporated full covariate adjustment, specifically adding an intermediate variable, namely the presence of incidence of stroke before the onset of disabling dementia (yes, no). SAS9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for analyses, and a two-tailed p value of < 0.05 denoted the presence of a statistically significant difference.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the 351 cases and 702 controls are shown in Table 1. Cases and controls showed no differences in overweight status, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or electrocardiogram abnormalities, but differed in terms of proportions of hyperglycemia and incidence of stroke before the onset of disabling dementia.

Table 1. Comparison of baseline characteristics between cases with disabling dementia and controls.

| Case | Control | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 351) | (N = 702) | ||

| At baseline | |||

| Age, years | 67.9 (0.4) | 67.8 (0.3) | 0.873 |

| Male, % | 35.6 (2.6) | 35.6 (1.8) | 1.000 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.1 (0.2) | 24.4 (0.1) | 0.196 |

| Overweight status, % | 15.7 (1.9) | 15.2 (1.4) | 0.856 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 135.0 (0.9) | 134.5 (0.7) | 0.676 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 78.9 (0.5) | 78.5 (0.4) | 0.499 |

| Hypertension, % | 58.7 (2.6) | 59.1 (1.9) | 0.894 |

| Antihypertensive medication use, % | 45.0 (2.6) | 42.5 (1.9) | 0.429 |

| Hyperglycemia, % | 24.2 (2.1) | 17.8 (1.5) | 0.014 |

| Glucose-lowering medication use, % | 6.0 (1.3) | 6.1 (0.9) | 0.927 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 202.0 (1.8) | 204.3 (1.3) | 0.304 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, % | 35.0 (2.6) | 38.0 (1.8) | 0.344 |

| Lipid-lowering medication use, % | 9.7 (1.6) | 10.7 (1.2) | 0.617 |

| Electrocardiogram abnormality, % | 11.1 (1.6) | 8.5 (1.1) | 0.179 |

| Current smoker, % | 17.7 (2.0) | 16.2 (1.4) | 0.560 |

| Past smoker, % | 11.1 (1.7) | 12.0 (1.2) | 0.684 |

| Current drinker, % | 30.0 (2.4) | 28.1 (1.7) | 0.550 |

| Ex-drinker, % | 5.4 (1.1) | 4.0 (0.8) | 0.296 |

| In followed-up period | |||

| Incidence of stroke, % | 23.9 (1.9) | 12.1 (1.4) | < 0.001 |

Mean values (standard error); Body mass index, body weight (kg) divided by squared body height (m); Overweight status, Body mass index, ≥ 25 kg/m2; Hypertension, systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg and/or antihypertensive medication use; Hypercholesterolemia, serum total cholesterol ≥ 220 mg/dl and/or lipid-lowering medication use; Hyperglycemia, fasting serum glucose ≥ 110 mg/dl or casual serum glucose ≥ 140 mg/dl and/or glucose-lowering medication use; Electrocardiogram abnormality, atrial fibrillation (Minnesota Codes, 8-3-1 or 8-3-2) and/or ST-T changes (Minnesota Code, 4-1 to 4-3 and/or 5-1 to 5-3); Current smoking status (current, past, never) and drinking status (current, ex-, never).

The proportion of subjects with each retinal finding was as follows: generalized arteriolar narrowing, 18.0%; arteriovenous nicking, 13.1%; any other retinopathy, 10.3%; increased arteriolar wall reflex, 9.6%; and focal arteriolar narrowing, 7.9%. As shown in Table 2, generalized arteriolar narrowing (case: 23.1% vs control: 15.7%, P = 0.003) and two or more retinal abnormalities (case: 18.2% vs control: 13.4%, P = 0.038) were more frequent in cases compared with controls. While arteriovenous nicking tended to be more frequent in cases than in controls (case: 15.7% vs control: 11.8%, P = 0.081), the other conditions occurred at similar rates in cases and controls.

Table 2. Comparison of proportions of retinal microvascular abnormalities between cases with disabling dementia and controls at baseline.

| Case | Control | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 351) | (N = 702) | ||

| Generalized arteriolar narrowing, % | 23.1 (2.1) | 15.7 (1.4) | 0.003 |

| Focal arteriolar narrowing, % | 7.7 (1.4) | 7.5 (1.0) | 0.935 |

| Arteriovenous nicking, % | 15.7 (1.8) | 11.8 (1.3) | 0.081 |

| Increased arteriolar wall reflex, % | 10.5 (1.6) | 9.3 (1.1) | 0.508 |

| Any other retinopathy, % | 11.4 (1.6) | 9.8 (1.2) | 0.432 |

| Hemorrhages, % | 7.1 (1.3) | 6.6 (0.9) | 0.728 |

| Microaneurysms, % | 2.6 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.5) | 0.191 |

| Exudates, % | 2.8 (0.9) | 2.6 (0.6) | 0.787 |

| New vessels, % | 1.1 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.4) | 0.654 |

| Laser photocoagulation scars, % | 0.9 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.4) | 0.822 |

| Total number of retinal abnormalities | |||

| 1 finding, % | 26.8 (2.3) | 22.8 (1.6) | 0.154 |

| ≥ 2 findings, % | 18.2 (1.9) | 13.4 (1.3) | 0.038 |

In parentheses, standard error; Optic disc swelling, which is one of any other retinopathy, was not observed in this study population.

As shown in Table 3, we tested the associations between each retinal vascular change and disabling dementia using conditional logistic regression models. Generalized arteriolar narrowing was associated with an increased risk of disabling dementia: crude OR, 1.66 (95% CI, 1.19–2.31), P = 0.003. The positive association remained statistically significant after adjustment for vascular risk factors: OR, 1.58 (1.12–2.23), P = 0.010 in Model 1, and after further adjustment for incidence of stroke before the onset of disabling dementia: OR, 1.48 (1.04–2.10), P = 0.029 in Model 2. Arteriovenous nicking was associated with borderline increased risk of disabling dementia: crude OR, 1.39 (0.96–2.01), P = 0.081; OR, 1.39 (0.95 – 2.03), P = 0.087 in Model 1; OR, 1.32 (0.90 –1.95), P = 0.154 in Model 2. Compared with no retinal abnormality, two or more retinal abnormalities were associated in a dose–response manner with an increased risk of disabling dementia even after adjustment for both vascular risk factors and incidence of stroke before the onset of disabling dementia. Other retinal vascular changes were not associated with increased risk.

Table 3. Conditional odds ratios for incidence of disabling dementia according to each retinal microvascular abnormality.

| N | N of case | Crude OR | Multivariable OR† | Multivariable OR‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | |||

| Generalized arteriolar narrowing | |||||

| Absent | 862 | 270 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Present | 191 | 81 | 1.66 (1.19–2.31) | 1.58 (1.12–2.23) | 1.48 (1.04–2.10) |

| P-value | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.029 | ||

| Focal arteriolar narrowing | |||||

| Absent | 973 | 324 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Present | 80 | 27 | 1.02 (0.63–1.65) | 1.01 (0.62–1.65) | 0.98 (0.60–1.62) |

| P-value | 0.934 | 0.960 | 0.946 | ||

| Arteriovenous nicking | |||||

| Absent | 915 | 296 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Present | 138 | 55 | 1.39 (0.96–2.01) | 1.39 (0.95–2.03) | 1.32 (0.90–1.95) |

| P-value | 0.081 | 0.087 | 0.154 | ||

| Increased arteriolar wall reflex | |||||

| Absent | 951 | 314 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Present | 102 | 37 | 1.16 (0.75–1.80) | 1.11 (0.71–1.73) | 1.11 (0.71–1.75) |

| P-value | 0.498 | 0.638 | 0.649 | ||

| Any other retinopathy | |||||

| Absent | 944 | 311 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Present | 109 | 40 | 1.19 (0.75–1.88) | 1.17 (0.73–1.88) | 1.20 (0.74–1.94) |

| P-value | 0.472 | 0.523 | 0.465 | ||

| Total number of retinal abnormalities | |||||

| Absent | 641 | 193 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 finding | 254 | 94 | 1.33 (0.97–1.83) | 1.31 (0.95–1.82) | 1.20 (0.86–1.67) |

| ≥ 2 findings | 158 | 64 | 1.62 (1.12–2.34) | 1.52 (1.04–2.23) | 1.50 (1.02–2.22) |

| P-value for trend | 0.005 | 0.016 | 0.035 |

OR, conditional odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Case-control matching variables: sex, age (± 3 years), and baseline-year.

Adjustment for vascular risk factors included overweight status, hypertension, hyperglycemia, hypercholesterolemia, electrocardiogram abnormality, current smoking status (current, past, never) and drinking status (current, ex-, never).

Further adjustment for incidence of stroke before the onset of disabling dementia.

Discussion

In this population-based nested case-control study, we found that a retinal vascular change, specifically generalized arteriolar narrowing i.e., a low ratio of arteriolar-to-venular diameter (2:3 or lower), was associated with an increased risk of disabling dementia, and the risk was unchanged after adjustment for vascular risk factors. While arteriovenous nicking showed a nonsignificant association with the risk, the other retinal abnormalities demonstrated no association. The total number of retinal abnormalities was also associated with the risk in a dose–response manner.

Previous longitudinal population-based studies have shown similar results linking retinal vascular changes to various indicators of incidence of dementia11–13, 17). According to an 11.6-year follow-up of men and women aged 55 years and older in the Rotterdam Study, generalized arteriolar narrowing and venular dilation tended to be associated with incidence of dementia9), although the study did not report arteriolar-to-venular ratios, which we used as a criterion for the diagnosis of generalized arteriolar narrowing. Their findings seem to be consistent with those of the present study because small arteriolar diameter and the venular dilation led to small arteriolar-to-venular ratio. In the Rotterdam Study, Ikram et al. found that venular dilation and arteriolar-to-venular ratio were associated with the progression of brain abnormalities detected by imaging, namely periventricular white matter lesions and lacunar infarcts over 3 years, whereas only venular dilation was strongly associated with the progression of subcortical white matter lesions12). Schrijvers et al. also reported a positive association between retinopathy (hemorrhages, microaneurysms, cotton wool spots, and laser photocoagulation scars) and the prevalence of dementia in a cross-sectional analysis, but no association with the risk of dementia in a prospective analysis13). In a 5-year follow-up of men and women aged 65 years and older of the Cardiovascular Health Study, they reported dose–response relationships between the total number of retinal vascular changes and incidence of disability, defined by executive dysfunction, slow gait, and depressive symptoms17). These results support the present finding that retinal vascular changes, represented by a small arteriolar-to-venular ratio, may help predict the risk of incidence of disabling dementia.

A 14-year follow-up of men and women aged 45–64 years of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study did not investigate the association between retinal vascular changes and the risk of dementia, but it did examine the association between this risk and cognitive decline16). The ARIC study found that cognitive decline was associated with focal arteriolar narrowing and retinopathy but not generalized arteriolar narrowing. They did not state the reason for the lack of correlation with generalized arteriolar narrowing. However, cognitive decline is not always a preclinical sign of dementia, and these two outcomes likely have different predictors10).

As previous studies have reported the associations of hypertension with generalized arteriolar narrowing29) and incidence of dementia30), hypertension could be one of the most important risk factors in the present study. However, we found no association between hypertension and incidence of disabling dementia among the subjects (average age = 68 years). The contribution of hypertension to the development of dementia may be weakened among the elderly. Ninomiya et al. reported the association of hypertension with incidence of all-cause dementia among middle-aged adults (average age = 57 years), but not among older adults (average age = 72 years)30). In addition, generalized arteriolar narrowing, associated with the risk of incidence of disabling dementia in our study, was likely to be caused by long-term hypertension31). On the other hand, focal arteriolar narrowing, which was not associated with the risk of incidence of disabling dementia in our study, was reported to be caused by short-term hypertension31). Thus, long-term hypertension from young to middle age may cause generalized arteriolar narrowing, and it may lead to incidence of disabling dementia in the elderly.

The most important strength of our study was the longitudinal population-based design. No other studies in Asia have shown the associations between comprehensive retinal vascular changes and the risk of disabling dementia. Some further methodologic issues should be discussed. We used a subjective grading system to evaluate retinal vascular changes. Such methods generally show lower reproducibility than computer-assisted systems32). However, the significant associations in the present study indicate that standardized qualitative grading is also useful in identifying persons at higher risks of disabling dementia.

Conclusion

We found that retinal vascular changes were positively associated with the risk of disabling dementia, even after adjustment for vascular risk factors and incidence of stroke before the onset of disabling dementia. Generalized arteriolar narrowing and total number of retinal abnormalities may be useful markers for identifying persons at higher risks of disabling dementia.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Emeritus Yoshio Komachi (University of Tsukuba), Professor Emeritus Hideki Ozawa (Oita Medical University), Former professor Minoru Iida (Kansai University of Welfare Sciences), Professor Emeritus Takashi Shimamoto (University of Tsukuba), Dr Yoshinori Ishikawa (Consultant of Osaka Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention), Professor Yoshihiko Naito (Mukogawa Women's University), Professor Tomonori Okamura (Keio University) for their support in conducting long-term cohort studies, and Drs Ai Ikeda, Hiroyuki Noda, Choy-Lye Chei for their valuable comments and data correction. The authors also thank the clinical laboratory technologists, public health nurses, engineers of the computer processing unit, nurses, and nutritionists in the Osaka Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and health professionals in the survey communities for their valuable assistance for their expert help.

CIRCS Investigators

The CIRCS Investigators are: Isao Muraki, Mina Hayama-Terada, Shinichi Sato, Yuji Shimizu, Takeo Okada, and Masahiko Kiyama, Osaka Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention; Akihiko Kitamura, Hironori Imano, Renzhe Cui and Hiroyasu Iso, Osaka University; Kazumasa Yamagishi and Tomoko Sankai, University of Tsukuba; Isao Koyama and Masakazu Nakamura, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center; Masanori Nagao and Mitsumasa Umesawa, Dokkyo Medical University School of Medicine; Tetsuya Ohira, Fukushima Medical University; Isao Saito, Ehime University; and Ai Ikeda, Koutatsu Maruyama and Takeshi Tanigawa, Juntendo University.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific (Research A, 26253043; Research C, 26460791), funded by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and by Health and Labour Science Research Grants for Dementia (H21-Ninchisho-Wakate-007; H24-Ninchisho-Wakate-003), funded by Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1). Etters L, Goodall D, Harrison BE: Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: a review of the literature. J Am Acad Nurse Pract, 2008; 20: 423-428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Muraki I, Yamagishi K, Ito Y, Fujieda T, Ishikawa Y, Miyagawa Y, Okada K, Sato S, Kitamura A, Shimamoto T, Tanigawa T, Iso H: Caregiver burden for impaired elderly Japanese with prevalent stroke and dementia under long-term care insurance system. Cerebrovasc Dis, 2008; 25: 234-240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, Decarli C, Greenberg SM, Iadecola C, Launer LJ, Laurent S, Lopez OL, Nyenhuis D, Petersen RC, Schneider JA, Tzourio C, Arnett DK, Bennett DA, Chui HC, Higashida RT, Lindquist R, Nilsson PM, Roman GC, Sellke FW, Seshadri S: Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke, 2011; 42: 2672-2713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). de la Torre JC: Impaired brain microcirculation may trigger Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 1994; 18: 397-401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Yukutake T, Yamada M, Fukutani N, Nishiguchi S, Kayama H, Tanigawa T, Adachi D, Hotta T, Morino S, Tashiro Y, Arai H, Aoyama T. Arterial stiffness determined according to the cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI) is associated with mild cognitive decline in communitydwelling elderly subjects. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2014; 21: 49-55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Yukutake T, Yamada M, Fukutani N, Nishiguchi S, Kayama H, Tanigawa T, Adachi D, Hotta T, Morino S, Tashiro Y, Aoyama T, Arai H. Arterial stiffness predicts cognitive decline in Japanese community-dwelling elderly subjects: a one-year follow-up study. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2015; 22: 637-644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Wong TY, McIntosh R: Systemic associations of retinal microvascular signs: a review of recent population-based studies. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt, 2005; 25: 195-204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Patton N, Aslam T, Macgillivray T, Pattie A, Deary IJ, Dhillon B: Retinal vascular image analysis as a potential screening tool for cerebrovascular disease: a rationale based on homology between cerebral and retinal microvasculatures. J Anat, 2005; 206: 319-348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Perez MA, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V: The use of retinal photography in nonophthalmic settings and its potential for neurology. Neurologist, 2012; 18: 350-355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Heringa SM, Bouvy WH, van den Berg E, Moll AC, Kappelle LJ, Biessels GJ: Associations between retinal microvascular changes and dementia, cognitive functioning, and brain imaging abnormalities: a systematic review. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2013; 33: 983-995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). de Jong FJ, Schrijvers EM, Ikram MK, Koudstaal PJ, de Jong PT, Hofman A, Vingerling JR, Breteler MM: Retinal vascular diameter and risk of dementia: the Rotterdam study. Neurology, 2011; 76: 816-821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Ikram MK, De Jong FJ, Van Dijk EJ, Prins ND, Hofman A, Breteler MM, De Jong PT: Retinal vessel diameters and cerebral small vessel disease: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Brain, 2006; 129: 182-188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Schrijvers EM, Buitendijk GH, Ikram MK, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Vingerling JR, Breteler MM: Retinopathy and risk of dementia: the Rotterdam Study. Neurology, 2012; 79: 365-370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Kawasaki R, Cheung N, Mosley T, Islam AF, Sharrett AR, Klein R, Coker LH, Knopman DS, Shibata DK, Catellier D, Wong TY: Retinal microvascular signs and 10-year risk of cerebral atrophy: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Stroke, 2010; 41: 1826-1828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Cheung N, Mosley T, Islam A, Kawasaki R, Sharrett AR, Klein R, Coker LH, Knopman DS, Shibata DK, Catellier D, Wong TY: Retinal microvascular abnormalities and subclinical magnetic resonance imaging brain infarct: a prospective study. Brain, 2010; 133: 1987-1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Lesage SR, Mosley TH, Wong TY, Szklo M, Knopman D, Catellier DJ, Cole SR, Klein R, Coresh J, Coker LH, Sharrett AR: Retinal microvascular abnormalities and cognitive decline: the ARIC 14-year follow-up study. Neurology, 2009; 73: 862-868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Kim DH, Chaves PH, Newman AB, Klein R, Sarnak MJ, Newton E, Strotmeyer ES, Burke GL, Lipsitz LA: Retinal microvascular signs and disability in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Ophthalmol, 2012; 130: 350-356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Wong TY: Is retinal photography useful in the measurement of stroke risk. Lancet Neurol, 2004; 3: 179-183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Mimoun L, Massin P, Steg G: Retinal microvascularisation abnormalities and cardiovascular risk. Arch Cardiovasc Dis, 2009; 102: 449-456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Henderson AD, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V: Hypertension-related eye abnormalities and the risk of stroke. Rev Neurol Dis, 2011; 8: 1-9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Ikeda A, Yamagishi K, Tanigawa T, Cui R, Yao M, Noda H, Umesawa M, Chei C, Yokota K, Shiina Y, Harada M, Murata K, Asada T, Shimamoto T, Iso H: Cigarette smoking and risk of disabling dementia in a Japanese rural community: a nested case-control study. Cerebrovasc Dis, 2008; 25: 324-331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Imano H, Kitamura A, Sato S, Kiyama M, Ohira T, Yamagishi K, Noda H, Tanigawa T, Iso H, Shimamoto T: Trends for blood pressure and its contribution to stroke incidence in the middle-aged Japanese population: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Stroke, 2009; 40: 1571-1577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Imano H, Iso H, Kiyama M, Yamagishi K, Ohira T, Sato S, Noda H, Maeda K, Okada T, Tanigawa T, Kitamura A, CIRCS Investigators : Non-fasting blood glucose and risk of incident coronary heart disease in middle-aged general population: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Prev Med, 2012; 55: 603-607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Chei CL, Yamagishi K, Ikeda A, Noda H, Maruyama M, Cui R, Imano H, Kiyama M, Kitamura A, Asada T, Iso H, CIRCS Investigators : C-reactive protein levels and risk of disabling dementia with and without stroke in Japanese: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Atherosclerosis, 2014; 236: 438-443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Yamagishi K, Ikeda A, Moriyama Y, Chei CL, Noda H, Umesawa M, Cui R, Nagao M, Kitamura A, Yamamoto Y, Asada T, Iso H, CIRCS Investigators : Serum coenzyme Q10 and risk of disabling dementia: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Atherosclerosis, 2014; 237: 400-403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Yamagishi K, Asada T. A prospective study of potential risk and protective factors for disabling dementia. Health and Labour Science Research Grants for Dementia (H21-Ninchisho-Wakate-007, in Japanese), 2010: 15-23 [Google Scholar]

- 27). Levy R: Aging-associated cognitive decline. Working Party of the International Psychogeriatric Association in collaboration with the World Health Organization. Int Psychogeriatr, 1994; 6: 63-68 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Iida M, Kitamura A: Usefulness of non-mydriasis fundus photography in health checkup. 2nd Ed. Tokyo: Vector Core, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 29). Wong TY, Mitchell P: Hypertensive retinopathy. N Engl J Med, 2004; 351: 2310-2317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Ninomiya T, Ohara T, Hirakawa Y, Yoshida D, Doi Y, Hata J, Kanda S, Iwaki T, Kiyohara Y: Midlife and latelife blood pressure and dementia in Japanese elderly. Hypertension, 2011; 58: 22-28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Wong TY, McIntosh R: Systemic associations of retinal microvascular signs: a review of recent population-based studies. Ophthal Physiol Opt, 2005; 25: 195-204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32). Couper DJ, Klein R, Hubbard LD, Wong TY, Sorlie PD, Cooper LS, Brothers RJ, Nieto FJ: Reliability of retinal photography in the assessment of retinal microvascular characteristics: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Ophthalmol, 2002; 133: 78-88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]