Abstract

The dissemination of carbapenem resistance in Escherichia coli has major implications for the management of common infections. bla KPC, encoding a transmissible carbapenemase (KPC), has historically largely been associated with Klebsiella pneumoniae, a predominant plasmid (pKpQIL), and a specific transposable element (Tn4401, ~10 kb). Here we characterize the genetic features of bla KPC emergence in global E. coli, 2008–2013, using both long- and short-read whole-genome sequencing. Amongst 43/45 successfully sequenced bla KPC-E. coli strains, we identified substantial strain diversity (n = 21 sequence types, 18% of annotated genes in the core genome); substantial plasmid diversity (≥9 replicon types); and substantial bla KPC-associated, mobile genetic element (MGE) diversity (50% not within complete Tn4401 elements). We also found evidence of inter-species, regional and international plasmid spread. In several cases bla KPC was found on high copy number, small Col-like plasmids, previously associated with horizontal transmission of resistance genes in the absence of antimicrobial selection pressures. E. coli is a common human pathogen, but also a commensal in multiple environmental and animal reservoirs, and easily transmissible. The association of bla KPC with a range of MGEs previously linked to the successful spread of widely endemic resistance mechanisms (e.g. bla TEM, bla CTX-M) suggests that it may become similarly prevalent.

Introduction

Carbapenemases have emerged over the last 15 years as a major antimicrobial resistance threat in Enterobacteriaceae, many species of which are major human pathogens1. They are enzymes with broad-spectrum hydrolytic activity targeting beta-lactams, and commonly associated with additional resistance mechanisms producing cross-resistance to other antimicrobial classes2. The Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) enzyme, encoded by alleles of the bla KPC gene, represents one of the five major carbapenemase families, others being the VIM, IMP and NDM metallo-beta-lactamases, and the OXA-48-like oxacillinases3.

KPC, unlike the other major carbapenemases, is an Ambler class A enzyme, with a serine in the active site, which hydrolyses penicillins, cephalosporins, aztreonam and carbapenems4. At least 18 variants are known, with nucleotide mutations across 20 positions (13 amino acid substitutions), and one variant with a 6 bp deletion (KPC-14, nucleotide positions: 722–727]. bla KPC is typically located within a 10 kb mobile transposon (Tn4401), most often on conjugative plasmids. In publicly available sequence data, bla KPC is mostly found as a single copy on any individual plasmid although it can exist in duplicate (6/133 [5%] KPC plasmid structures with Tn4401/bla KPC-2/3 duplications available in GenBank, March 2017 [Phan HTT, unpublished data]). It has also been described on multiple plasmids within the same isolate, and/or in multiple copies shared amongst the chromosome and plasmids5, 6.

The first KPC-producer, a K. pneumoniae strain harbouring bla KPC-2, was identified in 1996 in the eastern USA; since then, KPC-2 and KPC-3 (H272Y [C814T] with respect to KPC-2) have become widespread, and entrenched in endemic hotspots in the USA, Greece, Israel, China and Latin America7, 8. KPC-3 confers a 4-fold increase in ceftazidime resistance compared with KPC-29. The other variants remain relatively rare in published surveys. The spread of the epidemic K. pneumoniae lineage, ST258, is thought to have contributed significantly to global bla KPC-2/bla KPC-3 dissemination10, although these genes have now been observed in several species of Enterobacteriaceae5, 6.

Acquired carbapenem resistance in Escherichia coli was considered rare as recently as 2010, although the first cases of KPC-E. coli were observed as early as 2004–2005 in Cleveland (n = 1, KPC-211), New York City (n = 2, KPC-2), New Jersey, USA (n = 1, KPC-3)12, and Tel Aviv, Israel (n = 4, KPC-2)13, 14. No apparent epidemiological links between any of these cases were identified. Genotyping was limited at this time, but supported diversity being present in both host E. coli and bla KPC plasmid backgrounds. Since then, direct, plasmid-mediated transfer of bla KPC into E. coli within human hosts has been described15, and clusters of KPC-E. coli have been identified in several locations, from China to Puerto Rico16, 17, and in the context of clinical infections16, 17, asymptomatic colonization18 and the environment19.

More recently there has been concern around bla KPC in E. coli sequence type (ST) 131, a globally disseminated, clinically successful strain20–22. Notably, the H30R/C1 (fluoroquinolone-resistant) and H30Rx/C2 (fluoroquinolone and extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant) ST131 sub-lineages have previously emerged in association with particular drug resistance mechanisms, including the extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) gene, bla CTX-M-15 (clade C2)23, 24. Given the high rates of ST131 community and healthcare-associated infections25, and its capacity for asymptomatic gastrointestinal colonisation26, a stable association of ST131 with bla KPC could have important consequences for the management of E. coli infections14.

Despite these concerns, there are limited detailed molecular epidemiological data investigating the genetic structures associated with bla KPC in E. coli and the extent to which these may have been shared amongst Enterobacteriaceae. Here we used short-read (Illumina) and long-read (PacBio) sequencing to investigate 43 bla KPC-positive E. coli isolates obtained consecutively from global surveillance schemes (67 participating countries, 2008–2013), fully resolving the bla KPC-containing plasmids in 22 cases, and comparing these data with other bla KPC plasmid sequences.

Results

Global blaKPC-E. coli strains are diverse, even within the most prevalent ST, ST131, with evidence for local transmission

45 isolates were obtained from 21 cities in 11 countries across four continents (2010–2013; previous laboratory typing results summarized in Table S1). One isolate was bla KPC-negative on whole-genome sequencing (WGS; ecol_252), potentially having lost bla KPC during storage or sub-culture in the intervening time period between when the original typing was undertaken and the subsequent DNA extraction and preparation for WGS. For one isolate the WGS data were inconsistent with the lab typing results (ecol_451), likely representing a laboratory mix-up; ecol_252 and ecol_451 were therefore excluded from subsequent analyses. The other 43 isolates were successfully sequenced (for quality metrics see Table S1). Amongst these 43 isolates, twenty-one different E. coli STs were represented (Table 1; predicted in silico from WGS), including: ST131 [n = 16], ST410 [n = 4], ST38 [n = 3], ST10, ST69 [n = 2 each] (remaining isolates singleton STs).

Table 1.

Plasmid replicon families present by ST, using the PlasmidFinder database58.

| Inc type | Sequence type (number of isolates) | Total number of isolates [number of bla KPC plasmids] | p | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 (n=2) | 38 (3) | 44 (1) | 69 (2) | 101 (1) | 131 (16) | 155 (1) | 167 (1) | 182 (1) | 224 (1) | 297 (1) | 354 (1) | 361 (1) | 393 (1) | 410 (4) | 428 (1) | 540 (1) | 648 (1) | 744 (1) | 1193 (1) | 1431 (1) | |||

| A/C2 | 1 | 1[1] | 1 | 1[1] | 4[2] | 0.05 | |||||||||||||||||

| B/O/K/Z | 1 | 1[0] | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| FIA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 26[0] | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| FIB | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 29[0] | 0.14 | |||||||

| FII | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12[2] a,b | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4[2] | 1 | 1[1] c | 1 | 1 | 1 | 30[5]a,b,c | 0.34 | ||||||

| FIC(FII) | 1 | 1 | 2[0] | 0.67 | |||||||||||||||||||

| HI1b | 1 | 1[0] | 0.47 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| HI2+HIA2 | 1 | 1[0] | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| I1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8[0] | 0.02 | |||||||||||||||

| I2 | 1 | 1[0] | 0.67 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| L/M | 1[1] | 1 | 2[1] | 0.26 | |||||||||||||||||||

| N | 1[1] | 1 | 1[1] | 3[3] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4[2] | 1[1] | 1 | 1 | 16[8] | 0.009 | ||||||||||

| P | 1[1] | 1 | 2 | 4[1] | 0.47 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Q1 | 1 | 2[1] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6[1] | 0.31 | ||||||||||||||||

| R | 2[1] | 2[1] | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| U | 1[1] | 1[1] | 2[2] | 0.21 | |||||||||||||||||||

| X1 | 1 | 1 | 0.37 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| X3 | 3 | 3[0] | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| X4 | 4 | 3[0] | 0.98 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Y | 1 | 1[0] | 0.37 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| col | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12[5] d | 1[1] | 1[1] | 4 | 1 | 1 | 24[7]d | 0.04 | |||||||||||

| p0111 | 1 | 0.37 | |||||||||||||||||||||

Undmbers in square brackets represent the known subset of bla KPC plasmids in each cell. Exact test compares presence/absence of each Inc type by ST. The replicon type specifically associated with bla KPC could not be evaluated in 15 isolates, due to limitations of the assemblies.

aone multi-replicon plasmid also containing IncFIA.

bone multi-replicon plasmid also containing IncFIA and IncR.

cone multi-replicon plasmid also containing IncFIB.

done multi-replicon plasmid also containing repA.

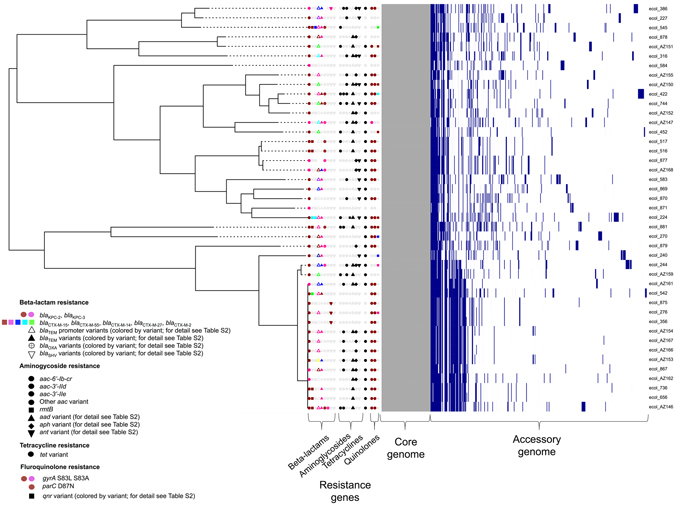

Of 16,053 annotated open reading frames (ORFs) identified across all KPC-E. coli isolates, only 2,950 (18.4%) were shared in all isolates (“core”), and a further 222 (1.4%) in 95- < 100% of isolates (“soft core”27). At the nucleotide level there were 213,352 single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in the core genome, consistent with the previously observed species diversity28. Resistance gene profiles also varied markedly between strains, with some harbouring several beta-lactam, aminoglycoside, tetracycline and fluoroquinolone resistance mechanisms (e.g. ecol_224) and others containing bla KPC only (e.g. ecol_584; Fig. 1). For the 16 KPC-ST131 strains, 4,071/7,910 (51%) ORFs were core, with 6,778 SNVs across the core genome of these isolates, again consistent with previous global studies of ST131 diversity23, 24 (Figure S1). Accessory genomes were highly concordant for some (e.g. ecol_356/ecol_276/ecol_875), but not all (e.g. ecol_AZ159/ecol_244) isolates that were closely related in their core genomes, supporting highly variable evolutionary dynamics between core and accessory genomes (Fig. 1). The geographic distribution of isolates closely related in both the core and accessory genomes supports local (e.g. ecol_AZ166, ecol_AZ167 [ST131, Beijing, China]) transmission of particular KPC-E. coli strains. The homology of genetic flanking motifs around the bla KPC genes in these closely related isolate pairs would also be consistent with this hypothesis, and less consistent with multiple acquisition events of bla KPC within the same genetic background, especially given the diversity in bla KPC flanking sequences observed across the rest of the dataset (see below).

Figure 1.

Phylogeny of KPC-Escherichia coli identified from global carbapenem resistance surveillance schemes, 2008–2013. Panels to the right of the phylogeny represent common resistance gene mechanisms (full details of resistance gene typing in Table S2), core and accessory genome components. For the accessory genome panel, blue represents annotated regions that are present, and white those that are absent.

blaKPC genes appear restricted to plasmid contexts in E. coli at present, but may exist in multiple copies on single plasmid structures or in high copy number plasmids

Thirty-four isolates (80%) contained bla KPC-2, and nine isolates (20%) bla KPC-3. Chromosomal integration of bla KPC has been described in other Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter spp. but remains rare5, 29, 30. There was no evidence of chromosomal integration of bla KPC in either the 18 chromosomal structures reconstructed from long-read sequencing, or based on review of the annotations in the bla KPC-containing contigs (derived from Illumina de novo assemblies) for the other 25 isolates. bla KPC alleles were not segregated by ST.

Estimates of bla KPC copy number per bacterial chromosome varied between <1 (ecol_879, ecol_881) and 55 (ecol_AZ152). In nine cases this estimate was ≥10 copies of bla KPC per bacterial chromosome (ecol_276, ecol_356, ecol_867, ecol_869, ecol_870, ecol_875, ecol_AZ150, ecol_AZ152, ecol_AZ159, Table S2). Six of these isolates contained bla KPC in a col-like plasmid context, in two cases the plasmid rep type was unknown, and in one case it was an IncN replicon. Plasmid copy number is associated with higher levels of antibiotic resistance if the relevant gene is located on a high-copy unit. Interestingly, high copy number plasmids are postulated to have higher chances of fixing in descendant cells, as they distribute more adequately by chance and without the requirement for partitioning systems31, and of being transferred in any conjugation event, either directly or indirectly32–34.

blaKPC and non-blaKPC plasmid populations across global KPC-E. coli strains are extremely diverse

Plasmid Inc typing revealed the presence of a median of four plasmid replicon types per isolate (range: 1–6; IQR: 3–5), representing wide diversity (Table 1). However, IncN, col, IncFIA and IncI1 replicons were disproportionately over-represented in certain STs (p < 0.05; Table 1). Amongst the 18 isolates that underwent PacBio sequencing, we identified 53 closed, non-bla KPC plasmids, ranging from 1,459 bp to 289,903 bp (Table S1; at least four additional, partially complete plasmid structures were present). Of these non-bla KPC plasmids, 10 (size: 2,571–150,994 bp) had <70% similarity (defined by percent sequence identity multiplied by proportion of query length demonstrating homology) to other sequences available in GenBank, highlighting that a proportion of the “plasmidome” in KPC-E. coli remains incompletely characterized. For the other 43 plasmids, the top match in GenBank was a plasmid from E. coli in 35 cases, K. pneumoniae in 5 cases, and Citrobacter freundii, Shigella sonnei, Salmonella enterica in 1 case each (Table S3).

Twenty-two bla KPC plasmid structures were fully resolved (17 from Pacbio data only, four from Illumina data only, 1 from both PacBio and Illumina data), ranging from 14,029 bp to 287,067 bp (median = 55,590 bp; IQR: 23,499–82,765 bp). These bla KPC-containing plasmids, and six additional cases where bla KPC was identified on a replicon-containing contig, were highly diverse based on Inc typing (Table S1). IncN was the most common type (n = 8/28 type-able bla KPC structures; 29%), followed by small, col-like plasmids (n = 6/28 [col-like plasmids with single replicons only]; 21%). Other less common types were: A/C2, FII(k), U (all n = 2); and L/M, P, Q1 and R (all n = 1). Four (14%) bla KPC plasmids were multi-replicon constructs, namely: col/repA, FIB/FII, FIA/FII, and FIA/FII/R.

Common IncN plasmid backbones have dispersed globally within E. coli

From GenBank, we selected all unique, fully sequenced IncN-bla KPC plasmid sequences (Table S4) for comparison, dating from as early as 2005, around the time of the earliest reports of KPC-producing E. coli. The plasmid backbones and flanking sequences surrounding bla KPC in these 16 plasmid references and a subset of 12 study sequences (see “Methods”) were consistent with multiple acquisitions of two known IncN-Tn4401-bla KPC complexes in divergent E. coli STs: firstly, within a Plasmid-9 (FJ223607, 2005, USA)-like background, and secondly, within a Tn2/3-like element in a Plasmid-12 (FJ223605, 2005, USA)-like background.

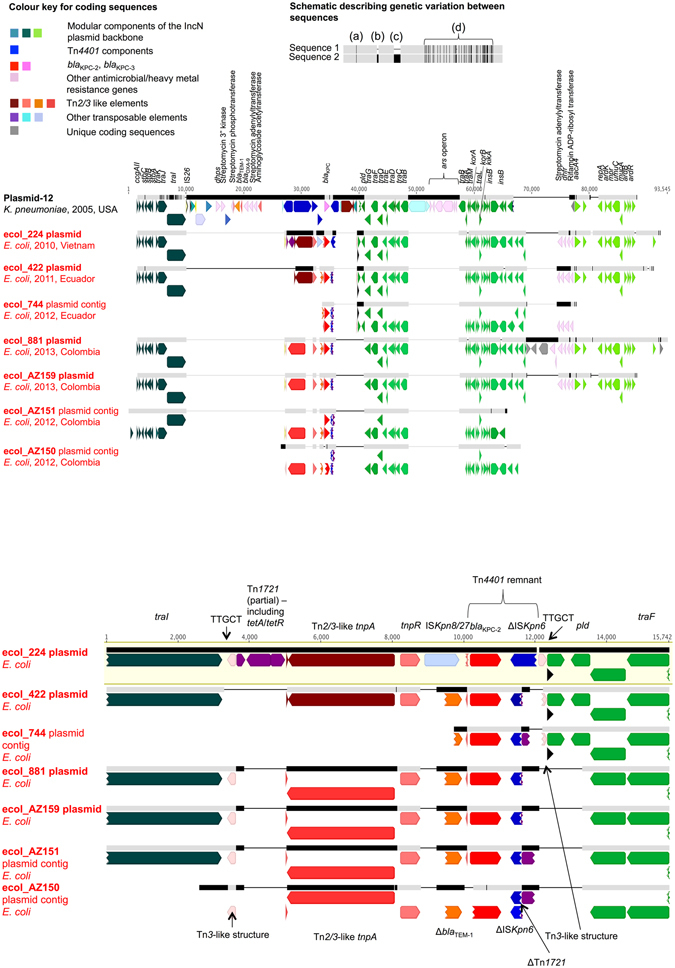

In the first instance, genetic similarities were identified between Plasmid-9, pKPC-FCF/3SP, pKPC-FCF13/05, pCF8698, pKP1433 (representing a hybrid IncN), and bla KPC plasmids from isolates ecol_516, ecol_517, ecol_656, and ecol_736 (this study). Plasmid-9 contains duplicate Tn4401b elements in reverse orientation with four different 5 bp flanking sequences in an atypical arrangement within a group II intron35. The backbone structures of the other plasmids in this group are consistent with a separate acquisition event of a Tn4401b element between the pld and traG regions within an ancestral version of the Plasmid-9 structure, with the generation of a flanking TTCAG target site duplication (TSD) (labelled as Plasmid 9-like plasmid (hypothetical), Fig. 2). International spread followed by local evolution both within and across species would account for the differences between plasmids, including: (i) nucleotide level variation (observed in all plasmids); (ii) small insertion/deletion events (observed in all plasmids); (iii) larger insertion/deletion events mediated by transposable elements (e.g. pCF8698_KPC_2); and (iv) likely homologous recombination, resulting in clustered variation within a similar plasmid backbone (e.g. ecol_656/ecol_736), as well as more distinct rearrangements, including the formation of “hybrid” plasmids (e.g. pKP1433)(Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison schematic of FJ223607-like (Plasmid 9-like) IncN plasmids (publicly available; this study), and their geographic origin/dates of isolation. Plasmid sequence names in red are those from this study, derived from PacBio data and closed (ecol_517, ecol_656) or incomplete plasmid structures (ecol_516, ecol_736) derived from Illumina data. Aligned bars adjacent to plasmid names represent plasmid sequences: light grey denotes regions with 100% sequence identity; black represents nucleotide diversity between sequences; and thin lines represent indels. Coding sequences are represented by fat arrows below individual sequence bars and are colour-coded as per the colour key. The inset schematic describing genetic variation between sequences depicts examples of evolutionary events identified: (a) single nucleotide level change, (b) small indels (≤100 bp), (c) large indels (>100 bp), (d) recombination events.

In Plasmid-12 (FJ223605), Tn4401b has inserted into a hybrid Tn2-Tn3-like element (with associated drug resistance genes including bla TEM-1, bla OXA-9, and several aminoglycoside resistance genes), albeit in the absence of target sequence duplication, possibly as the result of an intra-molecular, replicative transposition event generating mismatched target site sequences (L TSS = TATTA; R TSS = GTTCT). This complex is in turn located between two IS15DIV (IS15Δ)/IS26-like elements flanked by 8 bp inverted repeats, and located between the traI (891 bp from 3′ end) and pld loci (~28 Kb; Fig. 3A). The backbone components of the IncN Plasmid-12 are consistent with those seen in an NIH outbreak5 and in a rearranged version in a University of Virginia outbreak (CAV1043; 2008)6. From this study, plasmids from ecol_224, ecol_881, ecol_AZ159, ecol_422, and scaffolds from ecol_AZ151, ecol_744, ecol_AZ150 all share near identical structures to Plasmid-12, with clustered nucleotide level variation present in the traJ-traI genes, consistent with a homologous recombination event affecting this region, and evidence of sporadic insertion/deletion events (Fig. 3A). However, the bla KPC-Tn4401 structures in these isolates are almost entirely degraded by the presence of other mobile genetic elements (MGEs), including Tn2/Tn3-like elements, ISKpn8/27 and Tn1721. In ecol_224, bla KPC-2 has been inserted into the IncN backbone as part of two repeat, inverted Tn3-like structures, flanked by a TTGCT TSD, and closer to traI (136 bp from 3′ end) than the aforementioned IS15DIV (IS15Δ)/IS26-like complex in Plasmid-12 (Fig. 3B). Although it is not possible to accurately trace the evolutionary history of this genomic region given the available data, the presence of shared signatures of this structure in ecol_422, ecol_744, ecol_881, ecol_AZ159, ecol_AZ150 and ecol_AZ151 suggest a common acquisition, and multiple subsequent rearrangements mediated by the presence of the large number of MGEs flanking bla KPC-2.

Figure 3.

Comparison schematic of FJ223605-like (Plasmid-12-like) IncN KPC plasmids from this study. Panel 3A. Geographic origin, dates of isolation and overall alignment of plasmid/contig structures. Plasmid sequence names in red are those from this study, derived from PacBio data and closed (ecol_224, ecol_422, ecol_881, ecol_AZ159) or incomplete plasmid structures (ecol_744, ecol_AZ151, ecol_AZ150) derived from Illumina data. Aligned bars adjacent to plasmid names represent plasmid sequences: light grey denotes regions with 100% sequence homology; black represents nucleotide diversity between sequences; and thin lines represent indels. Coding sequences are represented by fat arrows below individual sequence bars and are colour-coded as per the colour key. The inset schematic describing genetic variation between sequences depicts examples of evolutionary events identified: (a) single nucleotide level change, (b) small indels (≤100 bp), (c) large indels (>100 bp), (d) recombination events. Panel 3B. Close-up of the region between traI and pld containing bla KPC-2 in study isolates only. Coding sequences are colour-coded as in Fig. 3A; sequence regions referred to in the text are annotated.

Col-like plasmids may represent an important vector of transmission for blaKPC in E. coli

Small col-like plasmids were the second most common type of plasmid carrying bla KPC in E. coli (n = 5 [plasmids with single replicons only]), but three of these were identical (bla KPC-2, 16,559 bp), all isolated in Pittsburgh, USA, from ST131 isolates across a two year timeframe (ecol_276 [PacBio; 2010], ecol_356 [2011], ecol_875 [2013]). These three isolates additionally contained FIA, FIB, FII, X3 and X4 replicons, suggesting stable persistence of a clonal strain + plasmids over time, consistent with both SNV/core and accessory genome analyses (Fig. 1, Figure S1).

The other two col-like plasmids effectively represent short stretches of DNA encoding different mobilization genes (mbeA/mbeC/mbeD) harnessed to Tn4401/bla KPC modules. The 5 bp sequences flanking Tn4401 were consistent with direct, intermolecular transposition in both cases (ecol_870: TGTTT-TGTTT; ecol_867: TGTGA-TGTGA). A col/repA co-integrate plasmid was also observed in this dataset (ecol_AZ161), in which Tn4401b was inserted between colE3 signature sequences and a Tn3 element (Tn4401 TSS: AGATA-GTTCT). The formation of such co-integrate plasmid structures in E. coli has also been previously described36, including that of a fused col/pKpQIL-like plasmid structure (pKpQIL being historically associated with bla KPC)37.

Col-like plasmids have been associated with KPC-producers in other smaller, regional studies21, 38. Of concern, these small vectors have been shown to be responsible for the inter-species diffusion of qnr genes mediating fluoroquinolone resistance, even in the absence of any obvious antimicrobial selection pressure39. The significant association of col-like plasmids with particular E. coli STs (predominantly ST131) in this study could be one explanation for the disproportionate representation of bla KPC in this lineage.

Diverse Tn4401 5 bp target site sequences (TSSs) support high transposon mobility

Complete Tn4401 isoforms flanking bla KPC-2 or bla KPC-3 were observed in only 24/43 (56%) isolates, including Tn4401a/a-like (n = 10; one isolate with a contig break upstream of bla KPC), Tn4401b (n = 12), and Tn4401d (n = 2) variants. Eleven different 5 bp target site sequence (TSS) pairs were identified, of which 7 (64%) were not observed in any comparison plasmid downloaded from GenBank (Table S5). Tn4401a had three different 5 bp TSSs, Tn4401b seven, and Tn4401d one. Most represented TSDs, but in three cases different 5 bp TSSs were flanking Tn4401, consistent with both direct inter- and replicative intra-molecular transposition events.

From the full set of GenBank plasmids and in vitro transposition experiments carried out by others, 30 different types of 5 bp TSS pairs have been characterized, seven in the experimental setting only40. The downloaded plasmids come from a range of species and time-points (2005–2014), although they may under-represent wider Tn4401 insertion site diversity as a result of sampling biases. Our data however would be consistent with significant Tn4401 mobility within E. coli following acquisition of diverse Tn4401 isoforms and/or represent multiple importation events into E. coli from other species.

The traditional association of blaKPC with Tn4401 has been significantly eroded in KPC plasmids in E. coli

Notably, in the other 19/43 (44%) isolates the Tn4401 structure had been degraded through replacement with MGEs, only some of which have been previously described41, 42. Two isolates had novel Tn4401Δb structures (upstream truncations by IS26 [ecol_270] or IS26-ΔIS5075 [ecol_584]). A Tn4401e-like structure (255 bp deletion upstream of bla KPC) was present in three isolates (ecol_227, ecol_316, ecol_583): this was further characterized in one complete PacBio plasmid assembly (ecol_316) and represented a rearrangement at the site of the L TSS of the ISKpn7 element. In this plasmid, a second, partial Tn4401 element was present without bla KPC, which would be consistent with an incomplete, replicative, intra-molecular transposition event (GGGAA = L TSS and R TSS on the two Tn4401b elements, in reverse orientation). Other motifs flanking bla KPC included: hybrid Tn2/Tn3 elements-ISKpn8/27-bla KPC (n = 1; ecol_224); IS26-ΔtnpR(Tn3)-ISKpn8/27- bla KPC-ΔTn1721-IS26 (n = 5; ecol_AZ153-AZ155, ecol_AZ166, ecol_AZ167); ISApu2-tnpR(Tn3)-ΔblaTEM -bla KPC- korC-klcA-ΔTn1721-IS26 (n = 1; ecol_542); IS26-tnpR(Tn3)-ΔblaTEM -bla KPC-korC-IS26 (n = 1; ecol_545); hybrid Tn2/Tn3 elements + ΔblaTEM-bla KPC-ΔTn1721 (n = 2; ecol_744, ecol_422), Tn3 elements-Δbla TEM-bla KPC- ΔTn1721 (n = 4; ecol_881, ecol_AZ151, ecol_AZ159, ecol_AZ150) and ΔTn3-Δ -ΔIS3000 (Tn3-like) (n = 1; ecol_AZ152). We were unable to assess the flanking context of bla KPC in ecol_452 due to limitations of the assembly.

This apparent diversity in independently acquired MGEs around the bla KPC gene extends the means by which bla KPC can be mobilized. Interestingly, as observed previously43, all the degraded Tn4401 sequences in this dataset were associated with variable stretches of flanking Tn2/3-like sequences, suggesting that the insertion of Tn4401 into a Tn2/Tn3-like context may have enabled the latter to act as a hotspot for the insertion of other MGEs6. A particular finding of note is the association with IS26, which has been linked to the dissemination of several other resistance genes in E. coli, including CTX-M ESBLs24, 44; is able to increase the expression of closely co-located resistance genes45; participates in co-integrate formation and hence plasmid rearrangement46; and enhances the occurrence of other IS26-mediated transfer events into plasmids harbouring IS26 46.

Discussion

This study of KPC-E. coli obtained from two global resistance surveillance schemes has demonstrated the diversity of genetic structures associated with bla KPC at all genetic levels, including: (i) host bacterial strain; (ii) plasmid types; (iii) associated transposable MGEs, including transposons and insertion sequences; and (iv) bla KPC alleles. This has previously been observed within institutional, poly-species outbreaks, particularly for non-E. coli Enterobacteriaceae5, 6, as well as in a more recent study of nine KPC-E. coli from the US47. We have identified global and regional bla KPC spread at the strain and plasmid levels, including signatures consistent with inter-species spread of plasmids, over short timeframes. Although the geographic reach of sampling has been more substantial than any other similar study, there are some limitations in the sampling consistency of both surveillance schemes22 (e.g. isolates from China were only submitted in 2008, 2012 and 2013).

We utilized long-read sequencing on only a subset of isolates, given resource limitations, allowing us to completely resolve chromosomal and plasmid structures in less than half the isolates. Nevertheless, despite this drawback, we have highlighted the extraordinary diversity present. This study, along with other recent analyses utilizing long-read sequencing to resolve antimicrobial resistance plasmids5, 6, also demonstrates the difficulty in making evolutionary comparisons for MGEs, given the absence of effective phylogenetic methods/tools to characterize their genetic histories which commonly involve genetic rearrangements, and evolutionary events that are not restricted to single nucleotide mutations.

This study has demonstrated the particular association of bla KPC in E. coli with IncN plasmids, previously associated with the spread of other antimicrobial resistance elements48, as well as col-like plasmids, which are small, potentially highly mobile, and generally high copy-number units. The traditional association of bla KPC with Tn4401 has apparently been eroded in E. coli, with the complete Tn4401 structure absent in 50% of strains investigated. This finding is in contrast to most global descriptions of K. pneumoniae where bla KPC has been stably associated with largely intact Tn4401 isoforms for more than a decade. Instead, other shorter MGEs, such as Tn2/Tn3-like elements and IS26, appear to be commonly involved in bla KPC dispersal in E. coli. These MGEs have been associated with the spread of multiple resistance mechanisms, such as bla TEM and bla CTX-M, and will potentially similarly contribute to the dissemination of bla KPC in E. coli. We did not undertake any functional assays investigating the dynamics of bla KPC transmission in E. coli to support this hypothesis, but this would be illuminating work for future study.

The global emergence and spread of bla KPC in E. coli has been driven by multiple mechanisms, including local and international spread of highly genetically related strains, exchange of plasmids with other Enterobacteriaceae and between E. coli lineages, transposition events within the species, and a breakdown of the traditional association of bla KPC with Tn4401. The genetic flexibility observed is impressive, especially given the timeframes and number of KPC-E. coli characterized. Tracking the spread of resistance genes given such multi-level genetic variability is complicated, even with a high-resolution typing method such as WGS. The association of E. coli, both a common pathogen and commensal in a wide range of environmental/animal reservoirs, with MGEs (col-like plasmids, IS26) that have been shown to facilitate the dissemination of other successful resistance genes even in the absence of antimicrobial selection pressures, may represent a difficult situation to control.

Methods

Isolate collection and sampling frames

Isolates were obtained from two global antimicrobial resistance surveillance schemes (The Merck Study for Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance Trends [SMART], 2008–2012; AstraZeneca global surveillance study of antimicrobial resistance, 2012–2013; 417 institutions operating in 95 countries), as previously described22. Of 55,874 isolates collected, 45 (0.08%) were positive for bla KPC by PCR (n = 7 from 2010, 10 from 2011, 13 from 2012, 15 from 2013; Table S1). Isolates had been previously characterized using partial, sequenced-based typing methods, including multi-locus sequence typing (MLST; Achtman scheme), fimH typing, PCR for beta-lactamases, strain/plasmid PFGE (Table S1)22.

DNA extraction and sequencing

All isolates were sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq; a subset of 18 were purposively selected for PacBio sequencing, to capture potential diversity across a range of years of isolation, geographic location, standard ST, plasmid size and resistance gene content (based on laboratory typing). DNA for sequencing was extracted from sub-cultures of bacterial stocks (frozen at −80 °C; cultured overnight on Columbia blood agar at 37 °C) using the Qiagen Genomic tip 100/G extraction kit, as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany; catalogue no: 10243).

DNA libraries for MiSeq sequencing were generated and normalized using 300 base, paired-end Nextera XT DNA library preparation kits (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). PacBio sequencing on the subset of strains was performed as previously described49; in these cases, the same DNA extract was used for both Illumina and PacBio sequencing approaches.

Sequence data processing

Illumina (short-read data)

Mapping-based approaches: Prior to reference-based mapping to the O150:H5 SE15 E. coli reference genome (Genbank accession: NC_013654), Illumina data were trimmed using cutadapt version 1.5. SE15, which is ST131, was chosen as the reference given the largest number of strains sequenced (and in the dataset) came from this ST. Repetitive regions of the reference were identified using self-self BLASTn analysis with default settings; these regions were then masked prior to mapping and base calling. Properly paired sequence reads were mapped to the reference using Stampy (v1.0.17) (Supplementary methods).

Single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) were determined across all mapped non-repetitive sites using SAMtools (version 0.1.18) mpileup. mpileup was run twice to separate high-quality base calls from low-quality base calls; variant call format (VCF) files of annotated variant sites were created using GATK (v1.4.21). Base calls derived from these two VCF files were filtered to retain only high quality calls (Supplementary methods).

Core variable sites (site called in all sequenced isolates, excluding “N” or “-” calls) derived from mapping to the SE15 reference were “padded” with invariant sites in a proportion consistent with the GC content and length of the reference genome (4.72 Mb, 51% average GC content), to generate a modified alignment of input sequences to generate phylogenies. Phylogenies were reconstructed using RaxML (Version 7.7.6)50, with a generalized time reversible model, four gamma categories (allowing for variable rates of mutation between sites), and bootstrapped 100 times.

De novo assemblies of Illumina data: De novo assemblies of short-read Illumina data for all isolates were generated using the A5-MiSeq pipeline (version 20140604; default settings)51, which includes adapter/low-quality region read trimming steps (Trimmomatic), initial contig assembly, crude scaffolding, misassembly correction and final scaffolding. We used the unscaffolded contigs file in subsequent analyses (*.contigs.fasta).

PacBio (long-read data)

DNA library preparation for and sequencing on the PacBio RSII were performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, using P5-C3 sequencing enzyme and chemistries respectively, and following a 7–50 kbp fragment selection step (full details in ref. 49). De novo assemblies were constructed using HGAP3 (version 2.2.0)52, resulting in phased chromosomal and plasmid contigs, which were manually closed by resolving and trimming overlapping repeats at the contig ends. Illumina reads for the respective isolate were then mapped to the resulting closed PacBio assemblies using bwa-MEM (version 0.7.9a-r786, default settings)53. Read pileups were visualized in Geneious54; mismatches between the sequence derived from mapping and the reference PacBio assemblies were inspected manually to identify the correct structure. Finally, to capture small plasmids that may have been filtered out due to size-selection of DNA fragments >7 kbp prior to PacBio sequencing, unmapped Illumina reads (extracted using the SAMtools view command, with the -f 12 flag) derived from this process were de novo assembled using the A5-MiSeq pipeline 2014060451; any assembled contigs were manually closed by assessing for and trimming overlapping repeats (100% match over a length of ≥100 bp; no match to any other contig in the assembly). The final consensus chromosomal and plasmid sequences derived from these processes were used in analyses and submitted to GenBank.

Automated and manual annotation of de novo assemblies

All plasmid structures and de novo assemblies were annotated using PROKKA55, with subsequent manual refinement of annotations for regions of interest using BLASTn56 and the NCBI bacterial and ISFinder databases57. Alignments of sequence structures were visualized and modified in Geneious. bla KPC-containing contigs identified in the de novo assemblies derived from Illumina data were manually inspected for overlapping repeats as above; if these were present, these contigs were considered additional putative KPC plasmids and trimmed and closed as above.

Core/accessory genome comparisons

These were undertaken using the pangenome pipeline, ROARY27, by inputting the *.gff files generated from the PROKKA annotation of each of the Illumina de novo assemblies (default settings). Comparisons were made separately for all isolates and the ST131 subset. The output gene_presence_absence.csv files were processed using the pheatmap function in R. Resistance genes were identified using ResistType, a command-line tool developed in-house that identifies the presence of reference loci in WGS data using both BLASTn against de novo assemblies and mapping-based approaches, and estimates copy number by comparing contig coverage at any given locus with median contig coverage [scripts, reference resistance gene database and manual available at: https://github.com/hangphan/resistType]. These features were plotted on the maximum likelihood phylogenies using the Ape package in R.

Comparisons with publicly available KPC plasmid sequences

All complete KPC RefSeq plasmid sequences available in GenBank in May 2015 were identified using the search terms “plasmid” + “KPC” + “complete sequence”. The resulting list was filtered manually to exclude any additional sequences present that were not complete plasmid sequences. In total 63 plasmid sequences were included (Table S5).

For the IncN plasmid comparisons, we included the following from our dataset: (i) six cases where PacBio sequencing had fully resolved the bla KPC IncN plasmid (ecol_224, ecol_422, ecol_517, ecol_656, ecol_881, ecol_AZ159); (ii) two cases where the IncN rep and bla KPC were co-located on the same, incomplete contig (ecol_516, ecol_736); and (iii) three cases where bla KPC was present in isolates containing an IncN rep and on contigs that showed high similarity to the IncN plasmid backbones under scrutiny (ecol_744, ecol_AZ150, ecol_AZ151).

Availability of Data and Materials

Sequencing datasets (Illumina raw reads, PacBio assemblies) are available in GenBank/SRA (project accession: PRJNA316786 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=316786)(Table S1).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contributions of the laboratory, healthcare and administrative teams contributing to the SMART and Astra Zeneca global antimicrobial resistance surveillance programs, and the Modernising Medical Microbiology Informatics Group (MMMIG). For this study, the MMMIG consisted of Adam Giess, Carlos Del Ojo Elias, Milind Acharya, Nicholas Sanderson, Trien Do and Vasiliki Kostiou. NS is currently funded through a Public Health England/University of Oxford Clinical Lectureship; the sequencing work was also partly funded through a previous Wellcome Trust Doctoral Research Fellowship (#099423/Z/12/Z). Additional funding support was provided by a research grant from Calgary Laboratory Services (#10006465), and by the Health Innovation Challenge Fund (a parallel funding partnership between the Wellcome Trust [WT098615/Z/12/Z] and the Department of Health [grant HICF-T5-358]). This research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Center (BRC) Program, and the Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Healthcare Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance at the University of Oxford, in partnership with Public Health England (PHE). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Author Contributions

N.S. and J.P. conceived of the study. Significant contributions to sample collection, laboratory processing and sequencing were made by G.P., L.W.A., L.P., P.B., M.R.M., N.S. and J.P. Short-read (Illumina) sequencing was performed by L.W.A. and L.P.; long-read (PacBio) sequencing by R.S. and A.K. Sequence data processing and analysis were performed by A.E.S., H.T.T.P. and N.S. N.S. drafted the manuscript, which was reviewed and improved by all authors, including A.S.W., T.E.A.P., D.W.C. and A.J.M.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-06256-2

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nordmann P, Naas T, Poirel L. Global spread of Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1791–1798. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doi Y, Paterson DL. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36:74–84. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1544208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordmann P, Poirel L. The difficult-to-control spread of carbapenemase producers among Enterobacteriaceae worldwide. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:821–830. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palzkill T. Metallo-beta-lactamase structure and function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1277:91–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06796.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conlan S, et al. Single-molecule sequencing to track plasmid diversity of hospital-associated carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:254ra126. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheppard AE, et al. Nested Russian Doll-Like Genetic Mobility Drives Rapid Dissemination of the Carbapenem Resistance Gene blaKPC. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:3767–3778. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00464-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munoz-Price LS, et al. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:785–796. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70190-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nordmann P, Cuzon G, Naas T. The real threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing bacteria. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:228–236. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehta SC, Rice K, Palzkill T. Natural Variants of the KPC-2 Carbapenemase have Evolved Increased Catalytic Efficiency for Ceftazidime Hydrolysis at the Cost of Enzyme Stability. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004949. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pitout JD, Nordmann P, Poirel L. Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, a Key Pathogen Set for Global Nosocomial Dominance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:5873–5884. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01019-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deshpande LM, Rhomberg PR, Sader HS, Jones RN. Emergence of serine carbapenemases (KPC and SME) among clinical strains of Enterobacteriaceae isolated in the United States Medical Centers: report from the MYSTIC Program (1999–2005) Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;56:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong T, et al. Escherichia coli: development of carbapenem resistance during therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:e84–86. doi: 10.1086/429822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Navon-Venezia S, et al. Plasmid-mediated imipenem-hydrolyzing enzyme KPC-2 among multiple carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli clones in Israel. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:3098–3101. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00438-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathers AJ, Peirano G, Pitout JD. The role of epidemic resistance plasmids and international high-risk clones in the spread of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28:565–591. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00116-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gona F, et al. In vivo multiclonal transfer of bla(KPC-3) from Klebsiella pneumoniae to Escherichia coli in surgery patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:O633–635. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo Y, et al. Characterization of KPC-2-producing Escherichia coli, Citrobacter freundii, Enterobacter cloacae, Enterobacter aerogenes, and Klebsiella oxytoca isolates from a Chinese Hospital. Microb Drug Resist. 2014;20:264–269. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2013.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robledo IE, Aquino EE, Vazquez GJ. Detection of the KPC gene in Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter baumannii during a PCR-based nosocomial surveillance study in Puerto Rico. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:2968–2970. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01633-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mavroidi A, et al. Emergence of Escherichia coli sequence type 410 (ST410) with KPC-2 beta-lactamase. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;39:247–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu G, Jiang Y, An W, Wang H, Zhang X. Emergence of KPC-2-producing Escherichia coli isolates in an urban river in Harbin, China. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;31:1443–1450. doi: 10.1007/s11274-015-1897-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai JC, Zhang R, Hu YY, Zhou HW, Chen GX. Emergence of Escherichia coli sequence type 131 isolates producing KPC-2 carbapenemase in China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:1146–1152. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00912-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Hara JA, et al. Molecular epidemiology of KPC-producing Escherichia coli: occurrence of ST131-fimH30 subclone harboring pKpQIL-like IncFIIk plasmid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4234–4237. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02182-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peirano G, et al. Global incidence of carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli ST131. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1928–1931. doi: 10.3201/eid2011.141388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petty NK, et al. Global dissemination of a multidrug resistant Escherichia coli clone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:5694–5699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322678111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoesser, N. et al. Evolutionary History of the Global Emergence of the Escherichia coli Epidemic Clone ST131. MBio7, doi:10.1128/mBio.02162-15 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Banerjee R, Johnson JR. A new clone sweeps clean: the enigmatic emergence of Escherichia coli sequence type 131. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4997–5004. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02824-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhong YM, et al. Emergence and spread of O16-ST131 and O25b-ST131 clones among faecal CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli in healthy individuals in Hunan Province, China. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2223–2227. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Page AJ, et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3691–3693. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Touchon M, et al. Organised genome dynamics in the Escherichia coli species results in highly diverse adaptive paths. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez T, Vazquez GJ, Aquino EE, Martinez I, Robledo IE. ISEcp1-mediated transposition of blaKPC into the chromosome of a clinical isolate of Acinetobacter baumannii from Puerto Rico. J Med Microbiol. 2014;63:1644–1648. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.080721-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen, L. et al. Genome Sequence of a Klebsiella pneumoniae Sequence Type 258 Isolate with Prophage-Encoded K. pneumoniae Carbapenemase. Genome Announc3, doi:10.1128/genomeA.00659-15 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Norman A, Hansen LH, Sorensen SJ. Conjugative plasmids: vessels of the communal gene pool. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364:2275–2289. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watve MM, Dahanukar N, Watve MG. Sociobiological control of plasmid copy number in bacteria. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paulsson J. Multileveled selection on plasmid replication. Genetics. 2002;161:1373–1384. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.4.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.San Millan A, et al. Small-plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance is enhanced by increases in plasmid copy number and bacterial fitness. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:3335–3341. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00235-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gootz TD, et al. Genetic organization of transposase regions surrounding blaKPC carbapenemase genes on plasmids from Klebsiella strains isolated in a New York City hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1998–2004. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01355-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peterson BC, Hashimoto H, Rownd RH. Cointegrate formation between homologous plasmids in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:1086–1094. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.3.1086-1094.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Villa L, et al. Reversion to susceptibility of a carbapenem-resistant clinical isolate of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing KPC-3. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:2482–2486. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Partridge SR, et al. Emergence of blaKPC carbapenemase genes in Australia. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;45:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pallecchi L, et al. Small qnrB-harbouring ColE-like plasmids widespread in commensal enterobacteria from a remote Amazonas population not exposed to antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1176–1178. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cuzon G, Naas T, Nordmann P. Functional characterization of Tn4401, a Tn3-based transposon involved in blaKPC gene mobilization. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:5370–5373. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05202-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen L, et al. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: molecular and genetic decoding. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:686–696. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shen P, et al. Novel genetic environment of the carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase KPC-2 among Enterobacteriaceae in China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4333–4338. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00260-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu L, et al. blaCTX-M-1/9/1 Hybrid Genes May Have Been Generated from blaCTX-M-15 on an IncI2 Plasmid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:4464–4470. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00501-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Partridge SR, Zong Z, Iredell JR. Recombination in IS26 and Tn2 in the evolution of multiresistance regions carrying blaCTX-M-15 on conjugative IncF plasmids from Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:4971–4978. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00025-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee KY, Hopkins JD, Syvanen M. Direct involvement of IS26 in an antibiotic resistance operon. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3229–3236. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3229-3236.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harmer CJ, Moran RA, Hall RM. Movement of IS26-associated antibiotic resistance genes occurs via a translocatable unit that includes a single IS26 and preferentially inserts adjacent to another IS26. MBio. 2014;5:e01801–01814. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01801-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chavda KD, Chen L, Jacobs MR, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. Molecular Diversity and Plasmid Analysis of KPC-Producing Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:4073–4081. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00452-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garcia-Fernandez A, et al. Multilocus sequence typing of IncN plasmids. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1987–1991. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mathers AJ, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing K. pneumoniae at a single institution: insights into endemicity from whole-genome sequencing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:1656–1663. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04292-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coil D, Jospin G, Darling AE. A5-miseq: an updated pipeline to assemble microbial genomes from Illumina MiSeq data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:587–589. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chin CS, et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2013;10:563–569. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kearse MM, et al. A. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Siguier P, Perochon J, Lestrade L, Mahillon J, Chandler M. ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D32–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carattoli A, et al. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequencing datasets (Illumina raw reads, PacBio assemblies) are available in GenBank/SRA (project accession: PRJNA316786 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=316786)(Table S1).