Abstract

Objective

To examine the determinants of potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) use.

Data Sources/Study Setting

U.S. nationally representative data on (n = 16,588) noninstitutionalized older adults (age ≥65) with drug use from the 2006–2010 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Study Design

We operationalized the 2012 Beers Criteria to identify PIM use during the year, and we examined associations with individual‐level characteristics hypothesized to be quality enabling or related to need complexity.

Principal Findings

Almost one‐third (30.9 percent) of older adults used a PIM. Multivariate results suggest that poor health status and high‐PIM‐risk conditions were associated with increased PIM use, while increasing age and educational attainment were associated with lower PIM use. Contrary to expectations, lack of a usual care source of care or supplemental insurance was associated with lower PIM use. Medication intensity appears to be in the pathway between both quality‐enabling and need‐complexity characteristics and PIM use.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that physicians attempt to avoid PIM use in the oldest old but have inadequate focus on the high‐PIM‐risk conditions. Educational programs targeted to physician practice regarding high‐PIM‐risk conditions and patient literacy regarding medication use are potential responses.

Keywords: Potentially inappropriate medications, older adults, Beers Criteria

Older adults are vulnerable to poor‐quality ambulatory management of their chronic conditions (American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel 2012), and in particular, to poor quality of medication prescribing (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013). The introduction of new medications for existing and previously untreatable conditions, coupled with the tendency to add new medications to a growing drug regimen for each condition, increases the risk of inappropriate medication use. This, in turn, may increase health resource use and expenditures (Aparasu and Mort 2004) and raise the risk of serious adverse reactions.

Potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs), based on criteria developed by Beers et al. (1991) and Beers (1997), are medications that should be avoided when (1) risks to older adult patients outweigh intended benefits, (2) better alternative medications exist, (3) the medication is used at an inappropriate dose or duration, or (4) there is a high risk for drug–disease interactions (American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel 2012). When the Beers Criteria were initially developed in 1991, they focused on medication use by nursing home residents. In 1997, the criteria were expanded to address medication use in all geriatric care settings. These latter criteria were subsequently updated in 2003 and most recently in 2012 (Fick et al. 2003; American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel 2012).

Prevalence estimates for PIMs represent an important quality metric, and the release of updated PIM criteria highlights the need for ongoing monitoring of drug use by older adults. A recent study (Davidoff et al. 2015) used U.S. nationally representative data from the 2006–2010 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey to examine the prevalence of PIM use based on the updated 2012 Beers Criteria. Among older adults with any prescription medication use, Davidoff et al. (2015) found that nearly one‐third (30.9 percent) used at least one PIM during the year.

In addition to examining overall prevalence, it is important to investigate associations between individual characteristics and PIM use to identify groups that may be disproportionately affected by inappropriate drug use and to better target interventions to reduce the use of PIMs. A number of previous studies have used nationally representative survey data to examine the relationship between patient characteristics and use of PIMs. Zhan et al. (2001) and Stuart et al. (2003) examined drug use among the community‐dwelling elderly and found that factors associated with an elevated risk of PIM use included female sex, self‐reported poor health, and more intensive medication use. Lau et al. (2005) examined drug use among the institutionalized elderly and found that more intensive medication use also increased the risk of PIM use in this population.

In this study, we contribute to the literature by examining the determinants of PIM use as defined by the updated 2012 Beers Criteria. We estimate multivariate models of the relationship between PIM use and a broad range of socioeconomic and health characteristics in a U.S. nationally representative sample of older adults who acquired at least one prescription medication during the year. We test the sensitivity of our results to the inclusion of variables that control for chronic conditions and the number of unique drugs used during the year, which elucidates the pathways through which other individual‐level characteristics are associated with PIM use.

Methods

Data

Data for this study were drawn from the 2006–2010 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component (MEPS), which collects nationally representative information including health care utilization and socioeconomic and health characteristics for the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population. MEPS households are interviewed in five survey rounds to obtain annual data reflecting a 2‐year reference period (Cohen 1997).

In each interview, MEPS respondents are asked for the names of drugs acquired since the last interview and the condition(s) each drug was intended to treat. Comparison of self‐reported drug use with administrative data shows that respondents tend to provide accurate reports of medications that were acquired to treat chronic conditions (Hill, Zuvekas, and Zodet 2011). This finding is significant for our research, as nearly all drugs identified as PIMs in the Beer's criteria are used to treat chronic conditions. The MEPS also contacts pharmacies to collect additional information including the National Drug Code (NDC), dose form, strength, and quantity dispensed. The MEPS Prescribed Medicines (PMED) files are linked, by NDC, to the Multum Lexicon database, a product of Cerner Multum, Inc. to obtain information on the active ingredients for each drug.

In addition to the PMED files, we used the MEPS Conditions files and the Consolidated Full Year files, which contain information on individuals' socioeconomic and health characteristics. We dropped 63 observations with missing health information. The resulting study sample includes 16,588 person‐year observations representing an average annual total of 35.8 million older adults who acquired at least one prescription medication during the year.

Dependent Variable: Any PIM Use

The outcome of interest in our study is use of PIMs by older adults. We used the methods described in Davidoff et al. (2015) to operationalize the 2012 update of the Beers Criteria. Specifically, we used the “qualified” PIM exposure measure, which identifies relevant drugs and then applies restrictions or qualifications related to daily dose, duration of use, conditions for which the drug is contraindicated, and conditions for which use of the drug is warranted. We used the MEPS PMED and Conditions files to construct the fill‐level and person‐level parameters needed to assess whether these additional criteria for inappropriate use were met. Then we used this information to construct a binary, person‐level indicator of any PIM use during the year.

Conceptual Framework

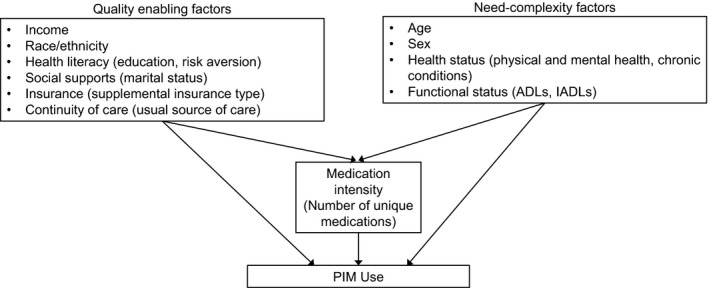

We conceptualize PIM use as a function of general access to high‐quality health care, and specific factors associated with medication appropriateness in older adults (Figure 1). Our model builds on the behavioral model of health care utilization (Andersen 1995; Andersen and Newman 2005) which posits that health service use is determined by individuals' predisposition to use health care services, factors which enable them to obtain services and need for care. To examine PIM use, we reorient the model to consider the quality of care received and focus on two types of individual characteristics: “quality enabling” factors that influence the quality of the provider and the patient–provider interaction, and “need‐complexity” factors that influence need for medications and the complexity of medication management.

Figure 1.

- Notes. Models also control for geographic region and urban/rural status (MSA/non‐MA) which may capture variation in access and practice patterns. Controls for year address changes in medication market availability and evidence of efficacy and risk over time. ADLs, activities of daily living; IADLs, instrumental activities of daily living.

Among the quality enabling factors in our model, we hypothesize that increases in income, racial‐ethnic majority status, and presence of supplemental health insurance will enable access to higher quality providers generally and HMO enrollment will be associated with enhanced quality of prescribing due to quality measurement initiatives. We hypothesize that factors associated with health literacy and patient engagement (increasing education, risk aversion) and social supports (marriage) will alter the nature of the patient–physician interaction, potentially improving quality. The availability of a usual source of care (USC) reflects general access to care, but it may particularly influence continuity of care and hence quality of prescribing. We also control for Census region, metropolitan statistical area (MSA) and year, which may capture variation in additional quality enabling factors such as quality of provider practice and temporal changes in prescription medication availability and awareness of risks to older adults. Elevated need for care may be a threat to quality, as poor overall health may create competing demands on the clinician and patient, or constrain therapeutic choices. To capture individuals' need for care and the complexity of necessary care, our base model includes measures of age, sex, self‐reported physical and mental health status, and indicators for disabilities related to activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL).

In addition to the base model, we test the sensitivity of results to controlling for chronic conditions and the intensity of medication use. We consider specific chronic conditions (e.g., arthritis or diabetes) that may increase the risk of PIM use because medications commonly used to treat them are associated with adverse effects for older adults. We also consider the number of unique medications used during the year. Several prior studies have used measures of medication intensity, which provide an alternative approach to capturing overall complexity of care and potential exposure to PIMs. As Figure 1 illustrates, we hypothesize that the number of unique medications may be in the pathway between some individual‐level characteristics and PIM use. For example, health insurance may lower individuals' out‐of‐pocket costs and increase the affordability of medications while health status will likely affect individuals' need for medications. Testing the sensitivity of results to inclusion of the number of drugs may provide information on the pathways by which individual characteristics are associated with PIM use. It is important to note, however, that our models do not include direct measures of many factors (e.g., quality of provider practice, medication availability) that are hypothesized to affect the quality of prescribing. Information on the independent variables in our models is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics and Bivariate Association of Socioeconomic and Health Characteristics with Any PIM Use: U.S. Noninstitutionalized Older Adults with Drug Use, 2006–2010

| Percent of All Older Adults | Percent with Any PIM Use | Chi‐Square Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | ||

| All older adults with drug use | 100.0 (0.0) | 30.9 (0.6) | |

| Quality enabling factors | |||

| Income as a percentage of the FPL | |||

| Poor (<100%) | 9.6 (0.3) | 32.2 (1.3) | * |

| Low income (100 <200%) | 25.3 (0.5) | 32.3 (0.9) | |

| Middle income (200 <400%) | 29.7 (0.6) | 31.9 (0.9) | |

| High income (≥400%) | 35.4 (0.7) | 28.7 (0.9) | |

| Race–ethnicity | |||

| White non‐Hispanic | 80.4 (0.7) | 30.8 (0.6) | † |

| Black non‐Hispanic | 8.4 (0.4) | 32.8 (1.5) | |

| Hispanic | 6.7 (0.4) | 30.7 (1.5) | |

| Other non‐Hispanic | 4.6 (0.5) | 30.0 (2.5) | |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 24.3 (0.6) | 34.4 (1.0) | * |

| High school graduate | 34.7 (0.7) | 30.1 (1.0) | |

| Some college | 18.5 (0.5) | 31.9 (1.2) | |

| College graduate | 12.1 (0.5) | 30.2 (1.6) | |

| Postgraduate | 10.3 (0.4) | 24.4 (1.5) | |

| More likely than others to take risks | |||

| Disagree/uncertain | 75.0 (0.5) | 31.4 (0.6) | † |

| Agree | 14.4 (0.4) | 29.6 (1.1) | |

| Missing | 10.6 (0.3) | 28.7 (1.3) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Currently married | 54.1 (0.8) | 30.9 (0.7) | † |

| Formerly married | 42.3 (0.8) | 31.3 (0.8) | |

| Never married | 3.7 (0.2) | 26.5 (2.2) | |

| Health insurance status | |||

| Private group | 41.5 (0.8) | 31.1 (0.9) | * |

| Medicaid | 10.5 (0.5) | 34.8 (1.3) | |

| Medicare HMO | 25.4 (0.7) | 29.3 (1.0) | |

| Other supplement or drug coverage | 16.1 (0.6) | 32.1 (1.3) | |

| No supplement and no drug coverage | 6.5 (0.3) | 26.3 (1.8) | |

| Usual source of care | |||

| Person | 34.0 (0.9) | 30.6 (1.0) | * |

| None or emergency room | 4.3 (0.2) | 22.4 (1.8) | |

| Hospital outpatient clinic | 12.4 (0.5) | 30.1 (1.4) | |

| Facility other than hospital | 46.3 (0.9) | 32.5 (0.8) | |

| Missing | 3.0 (0.2) | 25.1 (2.4) | |

| Census region | |||

| Northeast | 19.7 (0.8) | 24.6 (0.9) | * |

| Midwest | 22.3 (1.0) | 32.2 (1.5) | |

| South | 37.4 (1.1) | 34.2 (0.9) | |

| West | 20.6 (0.8) | 29.6 (1.1) | |

| MSA status | |||

| MSA | 80.5 (1.4) | 30.0 (0.6) | * |

| Non‐MSA | 19.5 (1.4) | 34.5 (1.5) | |

| Need‐complexity factors | |||

| Age | |||

| 65–74 | 51.3 (0.8) | 32.2 (0.8) | * |

| 75–84 | 35.2 (0.7) | 31.0 (0.9) | |

| 85 and older | 13.5 (0.5) | 25.6 (1.4) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 42.3 (0.4) | 28.8 (0.8) | * |

| Female | 57.7 (0.4) | 32.4 (0.7) | |

| Health status | |||

| Excellent/very good | 25.2 (0.5) | 23.9 (0.9) | * |

| Good | 36.9 (0.5) | 28.7 (0.8) | |

| Fair/poor | 37.8 (0.6) | 37.7 (0.8) | |

| Mental health status | |||

| Excellent/very good | 36.9 (0.7) | 26.2 (0.8) | * |

| Good | 43.4 (0.6) | 32.7 (0.7) | |

| Fair/poor | 19.7 (0.4) | 35.7 (1.2) | |

| ADL limitations | |||

| Yes | 11.4 (0.4) | 37.0 (1.5) | * |

| No | 88.6 (0.4) | 30.1 (0.6) | |

| IADL limitations | |||

| Yes | 20.1 (0.5) | 36.0 (1.2) | * |

| No | 79.9 (0.5) | 29.6 (0.6) | |

| Chronic conditions | |||

| Cardiovascular | |||

| Yes | 43.8 (0.6) | 34.9 (0.8) | * |

| No | 56.2 (0.6) | 27.8 (0.8) | |

| Central nervous system | |||

| Yes | 3.4 (0.3) | 35.0 (2.7) | † |

| No | 96.6 (0.3) | 30.7 (0.6) | |

| Mental health | |||

| Yes | 6.0 (0.4) | 45.4 (2.0) | * |

| No | 94.0 (0.4) | 30.0 (0.6) | |

| Arthritis | |||

| Yes | 9.8 (0.6) | 40.5 (1.5) | * |

| No | 90.2 (0.6) | 29.8 (0.6) | |

| Diabetes | |||

| Yes | 17.5 (0.6) | 43.5 (1.2) | * |

| No | 82.5 (0.6) | 28.2 (0.6) | |

Individuals are categorized as having a particular condition if they reported any ambulatory visit or hospital stay to treat the condition during the year.

*p < .05, † p ≥ .05.

ADL, activities of daily living; FPL, federal poverty level; HMO, health maintenance organization; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; MSA, metropolitan statistical area.Source. Authors' calculations from the 2006‐2010 MEPS HC.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated bivariate and multivariate relationships between PIM use and individuals' socioeconomic and health characteristics. We estimated an initial multivariate logit model that includes all variables described above except for chronic conditions and the number of unique drugs used. In our first alternative model, we added indicators for specific chronic conditions, and in the second alternative model, we added both chronic conditions and the number of unique drugs used.

The results of the multivariate logit models are presented as average marginal effects that reflect the difference in the predicted probability of any PIM use associated with a specific attribute relative to the reference category, holding all other covariates constant at their observed values. All analyses used weights to adjust for disproportionate sampling and nonresponse and Taylor series standard errors to adjust for the complex sample design of the MEPS.

Results

The older adults in our sample were predominantly of ages 65–74 (51.3 percent), white non‐Hispanic (80.4 percent), female (57.7 percent), and currently married (54.1 percent) (Table 1, column 1). Overall, an annual average of 30.9 percent of older adults used at least one PIM during the year, but there were large differences in PIM use across subgroups of the older adult population defined by quality‐enabling and need‐complexity characteristics (Table 1, column 2). For example, adults in fair/poor health (37.7 percent) were more likely to use a PIM than those in good health (28.7 percent) or very good/excellent health (23.9 percent).

In our base multivariate model (Table 2, column 1), there were several need‐complexity characteristics that were associated with the probability of PIM use. Older adults reporting good health (4.6 percentage points) or fair/poor health (12.3 percentage points) and those in good mental health (2.6 percentage points) were more likely to use PIMs than those reporting very good or excellent physical and mental health. Increasing age was associated with lower probability of PIM use, while females were 3.7 percentage points more likely than males to use at least one PIM during the year. Among the quality‐enabling factors in our model, results show that increasing educational attainment was associated with lower probability of PIM use, while those with no supplemental insurance and no drug coverage (−6.0 percentage points) relative to those with a private group supplement, and those who had no USC or who used the emergency department (−9.5 percentage points) relative to those with a regular physician provider were also less likely to use PIMs. There was also substantial variation across Census regions as older adults living in the Northeast were 5.6–8.9 percentage points less likely to use PIMs than those living in the South, Midwest, or West.

Table 2.

Marginal Effects of Socioeconomic and Health Characteristics on the Probability of Any PIM Use: U.S. Noninstitutionalized Older Adults with Drug Use, 2006–2010

| Model 1† | Model 2‡ | Model 3§ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal Effect (SE) | Marginal Effect (SE) | Marginal Effect (SE) | |

| Quality enabling factors | |||

| Income as a percentage of the FPL (ref: Poor <100%) | |||

| Low income (100 <200%) | 0.016 (0.014) | 0.014 (0.014) | 0.011 (0.013) |

| Middle income (200 <400%) | 0.022 (0.015) | 0.018 (0.014) | 0.020 (0.014) |

| High income (≥400%) | 0.007 (0.016) | 0.006 (0.016) | 0.006 (0.015) |

| Race–ethnicity (ref: White non‐Hispanic) | |||

| Black non‐Hispanic | −0.012 (0.016) | −0.015 (0.016) | 0.019 (0.015) |

| Hispanic | −0.039 (0.018)* | −0.045 (0.018)* | 0.004 (0.017) |

| Other | −0.017 (0.024) | −0.018 (0.023) | 0.019 (0.021) |

| Education (ref: Less than high school) | |||

| High school graduate | −0.028 (0.013)* | −0.025 (0.012)* | −0.032 (0.012)* |

| Some college | −0.001 (0.016) | −0.003 (0.016) | −0.021 (0.015) |

| College graduate | −0.004 (0.020) | −0.004 (0.020) | −0.020 (0.018) |

| Postgraduate | −0.052 (0.021)* | −0.054 (0.021)* | −0.060 (0.020)* |

| More likely than others to take risks (ref: Disagree/uncertain) | |||

| Agree | −0.002 (0.011) | −0.015 (0.015) | 0.005 (0.011) |

| Missing | −0.015 (0.015) | −0.001 (0.011) | 0.010 (0.014) |

| Marital status (ref: currently married) | |||

| Formerly married | −0.006 (0.011) | −0.011 (0.011) | −0.018 (0.011) |

| Never married | −0.042 (0.025) | −0.045 (0.025) | −0.033 (0.025) |

| Health insurance status (ref: Private group) | |||

| Medicaid | −0.006 (0.016) | −0.011 (0.016) | −0.003 (0.016) |

| Medicare HMO | −0.021 (0.014) | −0.016 (0.014) | −0.001 (0.013) |

| Other supplement or drug coverage | −0.017 (0.015) | −0.017 (0.015) | 0.008 (0.013) |

| No supplement and no drug coverage | −0.060 (0.019)* | −0.058 (0.019)* | −0.013 (0.020) |

| Usual source of care (ref: Person) | |||

| None or emergency room | −0.095 (0.026)* | −0.080 (0.026)* | −0.041 (0.025) |

| Hospital outpatient clinic | −0.007 (0.015) | −0.006 (0.015) | −0.012 (0.014) |

| Facility other than hospital | 0.013 (0.013) | 0.009 (0.013) | 0.000 (0.012) |

| Missing | −0.077 (0.030)* | −0.069 (0.030)* | −0.027 (0.030) |

| Census region (ref: Northeast) | |||

| Midwest | 0.072 (0.018)* | 0.076 (0.018)* | 0.058 (0.016)* |

| South | 0.089 (0.014)* | 0.091 (0.014)* | 0.070 (0.012)* |

| West | 0.056 (0.016)* | 0.058 (0.016)* | 0.054 (0.014)* |

| MSA status (ref: Non‐MSA) | |||

| MSA | 0.030 (0.014)* | 0.028 (0.014)* | 0.021 (0.013) |

| Need‐complexity factors | |||

| Age (ref: 65–74) | |||

| 75–84 | −0.029 (0.011)* | −0.025 (0.011)* | −0.033 (0.011)* |

| 85 and older | −0.097 (0.017)* | −0.080 (0.017)* | −0.075 (0.016)* |

| Sex (ref: male) | |||

| Female | 0.037 (0.011)* | 0.036 (0.011)* | 0.021 (0.011) |

| Health status (ref: Excellent/very good) | |||

| Good | 0.046 (0.014)* | 0.029 (0.014)* | −0.023 (0.013) |

| Fair/poor | 0.123 (0.015)* | 0.088 (0.015)* | −0.021 (0.015) |

| Mental health status (ref: Excellent/very good) | |||

| Good | 0.026 (0.013)* | 0.024 (0.013) | 0.016 (0.012) |

| Fair/poor | 0.014 (0.016) | 0.007 (0.016) | 0.010 (0.015) |

| ADL limitations (ref: No) | |||

| Yes | 0.027 (0.017) | 0.027 (0.017) | 0.014 (0.016) |

| IADL limitations (ref: No) | |||

| Yes | 0.029 (0.016) | 0.007 (0.015) | −0.017 (0.014) |

| Conditions | |||

| Cardiovascular | 0.033 (0.009)* | −0.027 (0.009)* | |

| Central nervous system | −0.004 (0.027) | −0.005 (0.026) | |

| Mental health | 0.086 (0.019)* | 0.032 (0.017) | |

| Arthritis | 0.071 (0.015)* | 0.041 (0.013)* | |

| Diabetes | 0.097 (0.012)* | 0.022 (0.014) | |

| Number of unique drugs used | 0.052 (0.001)* | ||

Individuals are categorized as having a particular condition if they reported any ambulatory visit or hospital stay to treat the condition during the year.

†Base model.

‡Model controls for chronic conditions.

§Model controls for chronic conditions and count of unique drugs used. All models include a set of year dummy variables.

*p < .05.

ADL, activities of daily living; FPL, federal poverty level; HMO, health maintenance organization; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; MSA, metropolitan statistical area.

Source. Authors' calculations from the 2006‐2010 MEPS HC.

When we added measures to capture specific high‐PIM‐risk conditions (Table 2, column 2), we found that older adults reporting treatment for diabetes (9.7 percentage points), arthritis (7.1 percentage points), mental health conditions (8.6 percentage points), and cardiovascular conditions (3.3 percentage points) were all more likely than others to use at least one PIM during the year. Otherwise, there were no qualitative changes in the results for individual characteristics except that the effect for good mental health lost statistical significance.

In the final model (Table 2, column 3), our results indicate that each additional drug an individual used during the year was associated with a 5.2 percentage point increase in his or her probability of using a PIM. Among need‐complexity factors, only age and arthritis had marginal effects that were qualitatively similar to previous models, while the effect of cardiovascular disease switched from a positive to a negative effect. Among the quality‐enabling factors, only education and Census region remained highly statistically significant.

Discussion

In this study, we used nationally representative data on older adults with prescription drug use to examine the relationship between individual‐level socioeconomic and health characteristics and use of PIMs. Consistent with our hypotheses, we found that worse general health status and the presence of specific “high‐PIM‐risk” conditions were associated with PIM use, while increasing education was associated with lower probability of PIM use. Contrary to expectations, we found that increasing age, lack of supplemental insurance, and lack of a USC or receipt of care in an emergency department were associated with lower likelihood of PIM use. While we found that each additional drug an individual used during the year was associated with an increase in the probability of PIM use, our model building exercise strongly suggests that intensity of medication use is in the pathway between several quality‐enabling and need‐complexity factors and PIM use, and should not be included in the main model. Focusing on the results of our second model, which controlled for chronic conditions but not the number of drugs used, can more effectively inform efforts to target subgroups at higher risk of PIM use.

Despite the ongoing high prevalence of PIM use, we find some potentially encouraging signs and directions for future interventions. Among the need‐complexity factors, the association between increasing age and reduced likelihood of PIM use is consistent with other studies (Goulding 2004; Rothberg et al. 2008; Olfson, King, and Schoenbaum 2015) and may reflect increased attention to patient safety concerns and avoidance of PIMs as physicians treat increasingly older patients. If this interpretation is correct, then it suggests physician awareness and application of the Beers Criteria, albeit while using clinical discretion for younger and presumably healthier patients. On the other hand, the strong associations between the presence of cardiovascular and mental health conditions, arthritis and diabetes and PIM use suggest the need to continue education programs directed at physicians, as well as increased use of prompts and other reminders that may be programmed into electronic medical record and prescribing systems. These types of interventions have been studied but are not yet widely implemented (Agostini, Zhang, and Inouye 2007; Tamblyn et al. 2012).

Among the quality enabling factors, PIM use tends to decline with higher levels of education. One possible explanation is that education increases health literacy, enhances patient–physician engagement, and improves the allocative efficiency of health care use (Miller and Pylypchuk 2014). Although it is difficult to compensate for prior low levels of educational attainment among older adults, ongoing efforts to improve health literacy, including periodic medication reviews with primary care physicians and pharmacists, may fill that gap over time. Older adults with supplemental insurance through a private group policy were more likely than those with no supplemental insurance to receive a PIM. This descriptive finding suggests a role for Medigap carriers and other insurers in conducting drug utilization review to identify PIM use in their covered populations. The strong variation across Census regions, controlling for a broad range of individual characteristics, suggests differences in practice patterns or other factors that differ across regions but could not be included in our models.

Limitations

Despite the strengths of our study, it is subject to several limitations. The outcome measure of PIM use was based on the updated 2012 Beers Criteria (American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel 2012), but it was applied to the 2006–2010 MEPS data, which was the most recently available data. As our data predate the release of the 2012 update to the Beers Criteria, our results provide a benchmark to assess the impact of the updated criteria over time. Much of the evidence used to update the Beers Criteria information in the 2012 guidelines may have been available to clinicians during our study period. The alternative approach, using the earlier (2003) version of the Beers Criteria, would have missed several PIMs related to medications that entered the market in the intervening years. In addition, the 2003 version lacked many of the refinements in the 2012 version concerning when use of a specific medication was considered to be inappropriate. Hence, it is difficult to assess the exact impact on our findings.

We note that many factors that may affect the quality of prescribing were not measured in the dataset and could not be included in our models. To assess the role of factors such as physician knowledge would require supplemental primary data collection, which was not feasible. In addition, some variables in our models may be endogenous. In particular, a number of unmeasured individual factors such as demand for quality care, knowledge of health conditions, and beliefs about the efficacy of medications may influence insurance status, type of USC, and the probability of PIM use. As a result, the marginal effects for insurance and USC may be biased. Finally, our analyses are largely descriptive in nature—we do not examine the causal relationship between PIM use and quality‐enabling and need‐complexity variables in our models.

Conclusion

Prescription drugs are important in the management of acute and chronic diseases. Older adults, commonly prescribed multiple prescription drugs due to complex medical problems, are increasingly at risk of PIM use. PIM use is often associated with increased adverse drug events in the older adults with implications for poor health outcomes, increased health resource use, and increased health care costs. Despite significant attention to the risk of PIM use, our results indicated that PIM use is highly prevalent among older adults. However, our results suggest that physicians attempt to avoid PIM use in the oldest old, and therefore educational programs may encourage physicians to apply the criteria to the younger old. Educational interventions that improve patient literacy around their medication use are also likely to reduce PIM use over time.

Supporting information

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This research was conducted while Edward Miller, Eric Sarpong, Amy Davidoff, and Eunice Yang were employed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Nicole Brandt was employed by the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and Donna Fick was employed by Penn State University. Donna Fick receives partial support from a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research R01 NR011042. Amy Davidoff's spouse receives research funding and serves on an advisory board for Celgene Pharmaceuticals. This would in no way influence her work on this study or manuscript. Donna Fick is a consultant and cochair for the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Beers Criteria Update and Nicole Brandt is also an author and contributor. AGS had no role in this study or manuscript.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors, and no official endorsement by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the Department of Health and Human Services is intended or should be inferred.

References

- Agostini, J. V. , Zhang Y., and Inouye S. K.. 2007. “Use of a Computer‐based Reminder to Improve Sedative‐Hypnotic Prescribing in Older Hospitalized Patients.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 55 (1): 43–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel . 2012. “American Geriatrics Society Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 60 (4): 616–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, R. M. 1995. “Revisiting the Behavioral Model and Access to Medical Care: Does it Matter?” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36 (1): 1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, R. , and Newman J. F.. 2005. “Societal and Individual Determinants of Medical Care Utilization in the United States.” Milbank Quarterly 83 (4): 1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparasu, R. R. , and Mort J. R.. 2004. “Prevalence, Correlates, and Associated Outcomes of Potentially Inappropriate Psychotropic Use in the Community‐Dwelling Elderly.” The American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy 2 (2): 102–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers, M. H. 1997. “Explicit Criteria for Determining Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use by the Elderly: An Update.” Archives of Internal Medicine 157 (14): 1531–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers, M. H. , Ouslander J. G., Rollingher I., Reuben D. B., Brooks J., and Beck J. C.. 1991. “Explicit Criteria for Determining Inappropriate Medication Use in Nursing Home Residents.” Archives of Internal Medicine 151 (9): 1825–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2013. The State of Aging and Health in America 2013. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. W. 1997. Design and Methods of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component. Methodology Report no. 1. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff, A. J. , Miller G. E., Sarpong E. M., Yang E., Brandt N., and Fick D.. 2015. “Prevalence of Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults Using the 2012 Beers Criteria.” Journal of the American Geriatric Society 63 (3): 486–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick, D. M. , Cooper J. W., Wade W. E., Waller J. L., Maclean J. R., and Beers M. H.. 2003. “Updating the Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults: Results of a US Consensus Panel of Experts.” Archives of Internal Medicine 163 (22): 2716–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulding, M. R. 2004. “Inappropriate Medication Prescribing for Elderly Ambulatory Care Patients.” Archives of Internal Medicine 164 (3): 305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, S. C. , Zuvekas S. H., and Zodet M. W.. 2011. “Implications of the Accuracy of MEPS Prescription Drug Data for Health Services Research.” Inquiry 48 (3): 242–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau, D. T. , Kasper J. D., Potter D. E. B., Lyles A., and Bennett R. G.. 2005. “Hospitalization and Death Associated with Potentially Inappropriate Medication Prescriptions among Elderly Nursing Home Residents.” Archives of Internal Medicine 165 (1): 68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G. E. , and Pylypchuk Y.. 2014. “Marital Status, Spousal Characteristics, and the Use of Preventive Care.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 35 (3): 323–38. [Google Scholar]

- Olfson, M. , King M., and Schoenbaum M.. 2015. “Benzodiazepine Use in the United States.” JAMA Psychiatry 72 (2): 136–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg, M. B. , Pekow P. S., Liu F., Korc‐Grodzicki B., Brennan M. J., Bellantonio S., Heelon M., and Lindenauer P. K.. 2008. “Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Hospitalized Elders.” Journal of Hospital Medicine 3 (2): 91–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, B. , Kamal‐Bahl S., Briesacher B., Lee E., Doshi J., Zuckerman I. H., Verovsky I., Beers M. H., Erwin G., and Friedley N.. 2003. “Trends in the Prescription of Inappropriate Drugs for the Elderly between 1995 and 1999.” The American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy 1 (2): 61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamblyn, R. , Eguale T., Buckeridge D. L., Huang A., Hanley J., Reidel K., Shi S., and Winslade N.. 2012. “The Effectiveness of a New Generation of Computerized Drug Alerts in Reducing the Risk of Injury from Drug Side Effects: A Cluster Randomized Trial.” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 19 (4): 635–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, C. , Sangl J., Bierman A. S., Miller M. R., Friedman B., Wickizer S. W., and Meyer G. S.. 2001. “Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in the Community‐Dwelling Elderly.” Journal of the American Medical Association 286 (22): 2823–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.