Abstract

The discovery and development of novel anthelmintic classes is essential to sustain the control of socioeconomically important parasitic worms of humans and animals. With the aim of offering novel, lead-like scaffolds for drug discovery, Compounds Australia released the ‘Open Scaffolds’ collection containing 33,999 compounds, with extensive information available on the physicochemical properties of these chemicals. In the present study, we screened 14,464 prioritised compounds from the ‘Open Scaffolds’ collection against the exsheathed third-stage larvae (xL3s) of Haemonchus contortus using recently developed whole-organism screening assays. We identified a hit compound, called SN00797439, which was shown to reproducibly reduce xL3 motility by ≥ 70%; this compound induced a characteristic, “coiled” xL3 phenotype (IC50 = 3.46–5.93 μM), inhibited motility of fourth-stage larvae (L4s; IC50 = 0.31–12.5 μM) and caused considerable cuticular damage to L4s in vitro. When tested on other parasitic nematodes in vitro, SN00797439 was shown to inhibit (IC50 = 3–50 μM) adults of Ancylostoma ceylanicum (hookworm) and first-stage larvae of Trichuris muris (whipworm) and eventually kill (>90%) these stages. Furthermore, this compound completely inhibited the motility of female and male adults of Brugia malayi (50–100 μM) as well as microfilariae of both B. malayi and Dirofilaria immitis (heartworm). Overall, these results show that SN00797439 acts against genetically (evolutionarily) distant parasitic nematodes i.e. H. contortus and A. ceylanicum [strongyloids] vs. B. malayi and D. immitis [filarioids] vs. T. muris [enoplid], and, thus, might offer a novel, lead-like scaffold for the development of a relatively broad-spectrum anthelmintic. Our future work will focus on assessing the activity of SN00797439 against other pathogens that cause neglected tropical diseases, optimising analogs with improved biological activities and characterising their targets.

Keywords: ‘Open Scaffolds’ compound collection, Whole organism screening, Haemonchus, Nematodes, Anthelmintic

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

New chemical entity (SN00797439) with selective anthelmintic activity.

-

•

Active against the barber's pole worm and other parasitic nematodes.

-

•

Potential for neglected tropical disease pathogens following optimisation.

1. Introduction

Parasitic worms (helminths) of animals and humans cause chronic and often deadly diseases that have a major socioeconomic impact worldwide (Fenwick, 2012, Fitzpatrick, 2013). On one hand, in humans, the disease burden due to parasitic worms represents ∼14 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) globally, representing half of the DALYs caused by major neglected tropical diseases (Hotez et al., 2014, Hotez et al., 2016). On the other hand, in agricultural animals, the annual economic losses due to death, poor health and reduced productivity caused by parasitic worms are estimated at billions of dollars per annum worldwide (cf. Knox et al., 2012, Roeber et al., 2013). In Australia alone, worms of cattle and sheep cause economic losses estimated at 500 million dollars per annum (Lane et al., 2015). As no vaccines are available for the vast majority of these parasites, their control relies predominantly on the use of (usually) one of a small number of medicines (anthelmintics). These anthelmintics are only, at best, partially effective, and their excessive and widespread use, particularly in livestock animals, has led to serious drug resistance problems around the world (Kaplan and Vidyashankar, 2012, Wolstenholme and Kaplan, 2012, Kotze and Prichard, 2016). Therefore, the ongoing development of novel treatments is crucial for the control of parasitic worms of animals.

Despite some success through the discovery of, for example, monepantel (Kaminsky et al., 2008, Prichard and Geary, 2008) and derquantel (Little et al., 2011), there has been relatively limited progress in discovering and developing new drugs against parasitic roundworms (nematodes), because of major challenges associated with development and translation to the market (Geary et al., 2015). Major hurdles include achieving anthelmintic efficacy with an acceptable therapeutic index, the ability to develop formulations that deliver the pharmacokinetic profile necessary for efficacy, while maintaining the therapeutic index to support safety, as well as achieving human food safety requirements linked to the use of food animal products and a low cost of manufacturing the drugs (cf. Geary et al., 2015, Campbell, 2016).

In 2008, the Queensland Compound Library (QCL), now called Compounds Australia, established a dedicated compound management facility to augment capability in chemical screening and biomedical research, including the discovery of new anti-parasite drugs (Simpson and Poulsen, 2014). A key role of Compounds Australia has been to source small molecules, to consolidate them into a central repository that facilitates subsequent screening and to provide these molecules to laboratories around the world to support drug discovery efforts.

Currently, Compounds Australia maintains three main collections: ‘Open Scaffolds’ (with ∼33,400 compounds), ‘Open Academic’ (∼19,500) and ‘Open Drugs’ (∼2500; Food and Drug Administration [FDA]-approved) (Simpson and Poulsen, 2014). Each collection is well curated and characterized, with extensive information available on the physicochemical properties of compounds, including “rule-of-five” descriptors (chirality, hydrogen bonding acceptor and donors, logP and molecular weight), and chemical fingerprints. The ready availability of these resources provided us with a unique opportunity to evaluate selected compound groups for activity against parasitic nematodes using recently developed whole-organism screening assays. Therefore, we elected to screen prioritised compounds from the largest library, ‘Open Scaffolds’, against parasitic stages of the barber's pole worm, Haemonchus contortus (of ruminants), to identify hit compounds, and then characterise and assess them as nematocidal candidates.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. The compound library, and the selection and preparation of chemicals for screening

We purchased a prioritised set of compounds from the ‘Open Scaffolds’ collection from Compounds Australia, which contains a total of 33,999 chemicals representing 1226 scaffolds (Simpson and Poulsen, 2014). This collection contains novel, lead-like scaffolds (or chemotypes), with an average of 28 compounds per scaffold to allow meaningful structure-activity relationships (SAR) to be explored. For each compound, the simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) string was converted to SYBYL line notation (SLN; Homer et al., 2008) using SYBL software (www.certara.com/software/molecular-modeling-and-simulation/sybyl-x-suite/); using this approach, 33,949 compounds were annotated. Then, we selected a subset of representative compounds from this library using the following steps. First, we removed 213 pan assay interference compounds (PAINs) (Baell and Holloway, 2010, Baell, 2016). Second, we subjected the remaining chemicals to stringent physicochemical and structural filtering, in order to select compounds with the highest probability of permeating cells, being soluble and being chemically optimised as drugs, using the following criteria: mixtures, metals, isotopes: 0, minimum number of rings: 1, maximum number of rings: 4; minimum molecular weight: 150 kDa; maximum molecular weight: 400 kDa; hydrogen bond donors: ≤ 3; hydrogen bond acceptors: ≤ 6; minimum number of hydrogen bond acceptors: 1; maximum number of chiral centers: 3; maximum number of rotatable bonds: 10; this process removed 14,328 compounds, leaving 19,408 compounds. Third, compounds that were > 90% similar to each other in structure were removed, leaving a final set of 14,464 compounds. These 14,464 compounds (Supplementary File 1) were individually solubilised in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; cat no. 2225; Ajax Finechem, Australia) to achieve a stock concentration of 5 mM, and then diluted and tested for activity against H. contortus (see Subsection 2.2).

2.2. Screening and evaluation of the effects of compounds on H. contortus

2.2.1. Production of parasitic larvae

Haemonchus contortus (Haecon-5 strain) was maintained in experimental sheep in accordance with institutional animal ethics guidelines (permit no. 1413429; The University of Melbourne) as described previously (Preston et al., 2015). To produce exsheathed third-stage larvae (xL3s), L3s were exposed to 0.15% (v/v) of sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) for 20 min at 37 °C (Preston et al., 2015), washed five times in sterile saline (0.9%) and cultured in Luria Bertani medium (LB) and supplemented with final concentrations of 100 IU/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin and 2 μg/ml of amphotericin (antibiotic-antimycotic, cat. no. 15240-062; Gibco, Life Technologies, USA) (LB*). To produce fourth-stage larvae (L4s), xL3s were incubated in a water-jacketed CO2 incubator (model no. 2406 Shel Lab, USA) for 7 days at 38 °C and 10% v/v CO2 or until ≥ 80% of L3s had developed to the L4 stage.

2.2.2. Preparation of compounds for screening

Compounds were supplied from Compounds Australia at a concentration of 5 mM. Individual compounds were diluted to 40 μM in LB* containing 1% DMSO and dispensed in 50 μl into the wells of sterile 96-well flat bottom microplates (cat no. 3635; Corning 3650, Life Sciences, USA) using an automated, multi-channel pipetting platform (Viaflow Assist, Switzerland). LB* containing 1% DMSO and LB* were both included as negative controls in screening assays. The anthelmintics moxidectin (Cydectin®, Virbac, France) and monepantel (Zolvix®, Novartis Animal Health, Switzerland) were used as positive-control compounds in screening assays.

2.2.3. Screening of compounds for their effect on xL3 motility

The whole-organism screening assay developed by Preston et al. (2016a) was used to evaluate the effect of compounds on the motility of xL3s of H. contortus. On each 96-well plate, the positive-control compounds (moxidectin and/or monepantel) were arrayed in triplicate. Six wells were used for each negative control (LB* + 1% DMSO and LB* alone). Test compounds were arrayed in individual wells. Following dispensing into the plates, 300 xL3s in 50 μl of LB* were transferred to each well of each plate (with the exception of perimeter wells) using a multi-channel pipette (Finnpipette, Thermo Scientific). During dispensing, xL3s were kept in a homogenous suspension by bubbling air through the solution using an air pump (Airpump-S100; Aquatrade, Australia). Thus, following the addition of xL3s to individual wells, the final concentrations were 20 μM (compound) and 0.5% (DMSO).

Plates were incubated in a water-jacketed CO2 incubator at 38 °C and 10% v/v CO2. After 72 h, the plates were agitated (126 rotations per min) using an orbital shaker (model EOM5, Ratek, Australia) for 20 min at 38 °C. In order to capture the motility of xL3s at 72 h, a video recording (5 sec) was taken of each well on each plate as described previously (Preston et al., 2016a). Each 5 sec-video capture of each well was processed using a custom macro in the program Image J (1.47v, imagej.nih.gov/ij), which indirectly measured larval motility by quantifying the changes in light intensity over time (cf. Preston et al., 2016a).

Supplementary video related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpddr.2017.05.004.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

Five-second digital movies of live exsheathed third-stage larvae exposed to 20 μM of SN00797439 and 20 μM of each of the two positive-control compounds (i.e. monepantel and moxidectin); the negative control (LB* + 0.5% DMSO) does not contain compound.

2.2.4. Screening of compounds for their effect on the motility and development/growth of fourth-stage larvae (L4s)

The motility of L4s was evaluated using the same protocol as for xL3 (see Subsection 2.2.3; Preston et al., 2016a). Following the measurement of larval motility, plates were re-incubated for four more days in a humidified environment (water-jacketed CO2 incubator) at 38 °C and 10% v/v CO2. Then, worms were fixed with 50 μl of 1% iodine, and 30 worms from each well were examined at 20-times magnification (DP26 camera, Olympus, Japan) to assess their development based on the presence of a well-developed mouth/pharynx in H. contortus L4s (see Sommerville, 1966). The number of L4s was expressed as a percentage of the total worm number (n = 30). Compounds were tested in triplicate on three different days.

2.2.5. Analyses of results from bioassays using H. contortus

Raw data were normalised against values of the positive and negative controls to remove plate-to-plate variation by calculating the percentage of motility using the program GraphPad Prism (v.6 GraphPad Software, USA). A compound was recorded as having anti-xL3 activity if it reduced motility by ≥ 70% at 72 h, and was re-screened at 20 μM to confirm its inhibitory properties on motility.

For a compound that consistently reduced xL3 motility by ≥ 70%, an 18-point dose-response curve (two-fold serial dilutions; from 100 μM to 0.00076 μM) was produced for xL3 and L4, to establish its half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50). For xL3 and L4, motility was measured at 24 h, 48 h and 72 h, and L4 development at 7 days of incubation with each active compound (triplicate) (Subsection 2.2.3). Compound concentrations were transformed using the equation (x = log10 (concentration in nM)) and a log (agonist) versus response -- variable slope (four parameter) equation, in GraphPad prism v.6.07 was used to calculate IC50 values. For L4 development, IC50 values were calculated using the same approach. If a IC50 value could not be accurately calculated by the log (agonist) versus response -- variable slope (four parameter) equation, a range for the IC50 value was given.

2.3. Scanning electron microscopy

This microscopy technique was used to assess whether compounds that reduced motility by ≥ 70% caused structural damage to the larval stages of H. contortus, as described previously (Preston et al., 2016b). The xL3s and L4s were produced and cultured as described previously (Preston et al., 2015; 1, 2). Six replicates of 300 xL3s or L4s were incubated in 100 μM of each compound in LB* for 24 h at 38 °C and 10% v/v CO2. Larvae were pooled, washed 3 times in 0.9% saline at 9000 × g and resuspended in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Subsequently, the larvae were fixed and processed as described previously (Preston et al., 2016b). Larvae were imaged using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (XL30 Philips, Netherlands); six representative images were taken of each sample.

2.4. Evaluating compound activity on filarial worms

2.4.1. Procurement of filarial nematodes

The Filariasis Research Reagent Resource Center (Athens, Georgia, USA; http://www.filariasiscenter.org/) has official ethics approval to produce filarial nematodes in experimental animals. From this centre, we obtained fresh, live adults of Brugia malayi, produced in Meriones unguiculatus (jird) (Michalski et al., 2011, Mutafchiev et al., 2014). Fresh, live microfilariae of Dirofilaria immitis (Missouri strain) obtained from the bloods from dogs with patent infection (cf. Michalski et al., 2011, Mutafchiev et al., 2014) were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Life Technologies, USA).

2.4.2. Assessing compound activity against adults and microfilariae of B. malayi

A compound with known activity against H. contortus was purchased from ChemDiv (USA) and then dissolved in DMSO to reach a stock concentration of 30 mM, and then tested for its effect on the motility of adult female and male B. malayi (see Storey et al., 2014). First, adults were manually separated from each other with forceps, and individuals transferred to single wells of 24-well plates containing 500 μl of RPMI-1640 (Gibco, Life Technologies, USA) supplemented with 10 μg/ml of gentamycin and 2.5 μg/ml amphotericin B (designated RPMI*) at 37 °C. Two-fold dilutions (100 μM–0.97 μM) of each compound in 500 μl of RPMI* were tested in duplicate (adding the same volume to the wells). RPMI* plus 1% DMSO, but without compound, was added to four negative-control wells. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C and 5% v/v CO2. Subsequently, using the Worminator image analysis system (Storey et al., 2014), the motility of individual adult worms was recorded after 24 h and 48 h of incubation. In brief, at each time point, a video recording (1 min) was taken of each well on each plate until the standard deviation reached zero.

In addition, the effect of compounds on the production and motility of microfilariae originating from individual gravid females of B. malayi after 72 h of incubation was assessed. To do this, 200 μl of medium (RPMI* plus 1% DMSO) containing ∼100 microfilariae from individual wells were transferred to individual wells of a 96-well plate and recorded for 30 sec (in the same manner as for adult worms) using the Worminator. All assays were repeated thrice, and IC50 values were calculated using the log (agonist) versus response -- variable slope (four parameter) equation -- in GraphPad Prism (v.6 GraphPad Software).

2.4.3. Evaluating compound activity against microfilariae of D. immitis

To assess the effects on the microfilariae of D. immitis, compounds were serially diluted two-fold (100 μM–0.39 μM) in 96-well plates; RPMI* was used as the medium, and each compound dilution was tested in triplicate. Six wells contained RPMI* plus 1% DMSO (negative controls). In test wells, 50 μl of RPMI* containing ∼100 microfilariae were added to each well using a multi-channel pipette. Plates were then incubated at 37 °C and 5% v/v CO2. At 24 h and 48 h, plates were imaged for microfilarial motility using the Worminator (see Subsection 2.4.2). All assays were repeated thrice on different days, and IC50 values were determined using GraphPad prism (Subsection 2.2.5).

2.5. Assessing compound activity on adult A. ceylanicum and T. muris L1s

Adults of A. ceylanicum were collected from the small intestine of hamsters, which had been infected orally with 150 A. ceylanicum L3s for three weeks. For each compound, three worms were placed in each well of a 24-well plate, using 2 wells per compound. Levamisole (50 μM) was used as a positive-control compound. Worms were incubated in the presence of 50 μM of each compound, and culture medium, which was composed of Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum, 25 μg/ml of amphotericin B, 100 U/ml of penicillin and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin. Worms were kept in an incubator at 37 °C and 5% v/v CO2 for 72 h. Thereafter, the condition of the worms was microscopically evaluated.

For T. muris, 40 L1s were placed in each well of a 96-well plate and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% v/v CO2 in the presence of 100 μl RPMI-1640 medium with amphotericin B (12.5 μg/ml), penicillin (500 U/ml), streptomycin (500 μg/ml) and 100 μM of the compound to be tested. Levamisole (100 μM) was used as a positive-control compound. Each compound was tested in duplicate. At 24 h, the total number of L1s per well was counted. The larvae were then stimulated with 100 μl hot water and motile L1s were counted.

2.6. Assessing compound cytotoxicity and selectivity

Cell toxicity was assessed in a mammary epithelial cell line (MCF10A), essentially as described previously (Kumarasingha et al., 2016). In brief, MCF10A cells were seeded in black walled, flat bottom 384 well black walled plates (Corning, USA) at 700 cells/well using a BioTek 406 automated liquid handling dispenser (BioTek, Vermont, USA) in a total volume of 40 μl/well. Cells were cultured in DMEM-F12 containing 5% horse serum (Life Technologies, Australia), 20 ng/ml human epidermal growth factor (EGF, Life Technologies, Australia), 100 ng/ml cholera toxin (Sigma, Australia), 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma, Australia) and 10 μg/ml insulin (human; Novo Nordisk Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd, Australia). After an incubation for 24 h at 37 °C, 5% v/v CO2, the growth medium was aspirated and the cells were treated with test compounds, starting at 100 μM, and positive and negative controls (media ±1% DMSO, monepantel, moxidectin). The chemotherapeutic compound doxorubicin, starting at 10 μM, was also used as a positive control. Compounds were titrated to generate a five-point dose-response curve, in quadruplicate, using an automated liquid handling robot (SciClone ALH3000 Lab Automation Liquid Handler, Caliper Lifesciences, USA) and incubated for a further 48 h. Matched DMSO concentrations for each compound concentration were also tested separately to account for DMSO induced cell toxicity. To measure cell proliferation, cells were fixed and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 1:1000), and individual wells imaged at 10-times magnification, covering 16 fields (∼90% of well) using a high content imager (Cellomics CellInsight Personal Cell Imager, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) at a fixed exposure time of 0.12 sec. Viable cells were counted using the Target Activation BioApplication within the Cellomics Scan software (v.6.5.0, Thermo Scientific, USA) and normalised to the cell density in wells without compound. Toxicity due to DMSO was removed from the normalised cell density counts and IC50 values calculated from the variable slope four-parameter equation (v.6 GraphPad Software). Experiments were repeated twice on two different days using four technical replicates for each compound.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. The identification of compound SN00797439 with activity against parasitic stages of H. contortus

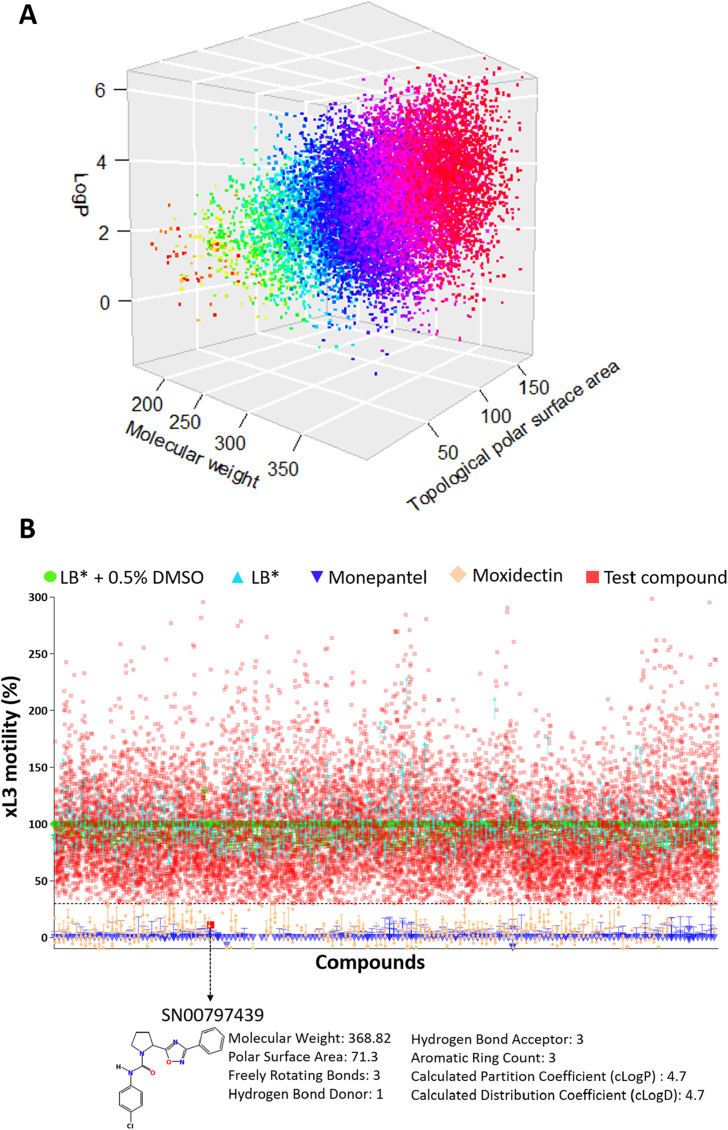

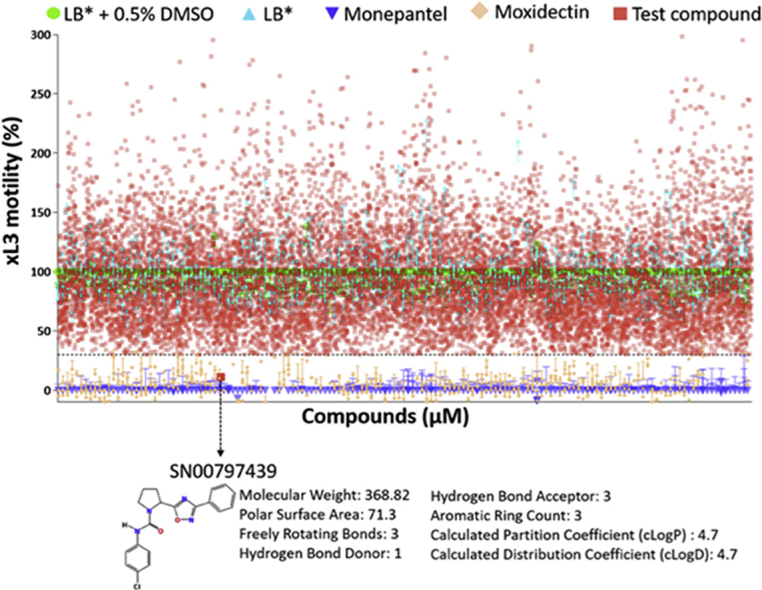

In the primary screen, we tested all 14,464 prioritised compounds from the ‘Open Scaffolds’ collection against H. contortus xL3s (Fig. 1A). Any compounds that consistently reduced xL3 motility (in independent screens) by > 70% at 72 h was recorded as a “hit” (Fig. 1B). Of all compounds tested, a chemical, designated SN00797439 (IUPAC name: N-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-(3-phenyl-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)-1-pyrrolidinecarboxamide) reduced xL3 motility by ≥ 70% in both the primary and subsequent confirmatory screens (Fig. 1B); this compound caused a “coiled” xL3 phenotype (Supplementary File 2). The chemical structure and predicted physicochemical properties of SN00797439 are given in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Panel A: Three-dimensional scatterplot displaying the physicochemical properties of molecular weights (in g mol−1), calculated partition coefficients (LogP) and topological polar surface areas (in Å2) of all 14,464 compounds prioritised from 33,999 compounds contained within the ‘Open Scaffolds’ collection. Panel B: Primary screen of the 14,464 compounds at the concentration of 20 μM identified compound SN00797439 to inhibit the motility of exsheathed third-stage larvae (xL3) by ≥ 70% compared with negative (LB* + 0.5% dimethyl sulfoxide; DMSO) and positive controls (monepantel and moxidectin). The chemical structure and predicted physicochemical properties of SN00797439 are listed at the bottom of the image.

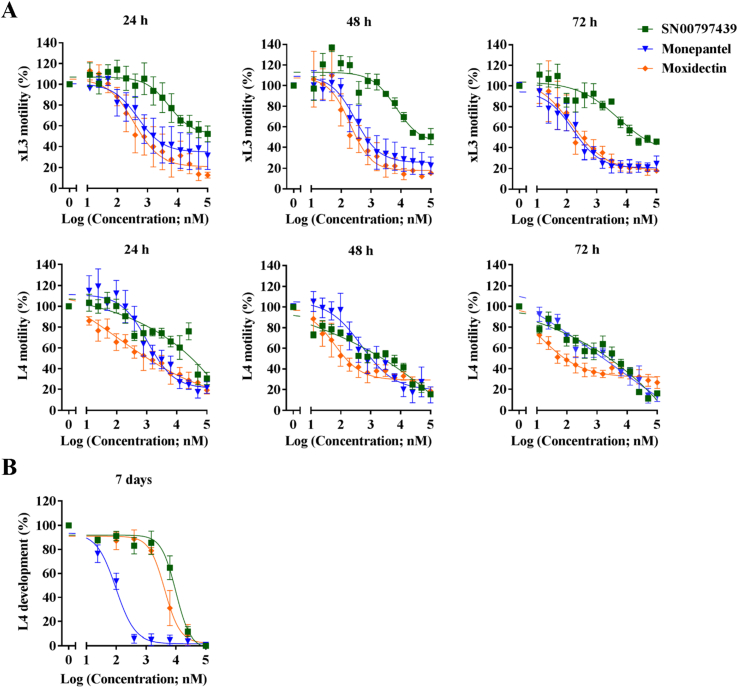

Dose-response curves (two-fold serial dilutions from 100 μM to 0.00076 μM) showed that SN00797439 inhibited xL3 motility, with IC50 values of 3.46 ± 0.82 μM (24 h), 10.08 ± 2.06 μM (48 h), and 5.93 ± 1.38 μM (72 h) (Fig. 2; Table 1); these IC50 values were comparable with those of monepantel and moxidectin (positive-control compounds).

Fig. 2.

Dose-response curves for compounds SN00797439 on larval stages of Haemonchus contortus in vitro with reference to the positive-control compounds monepantel and moxidectin. Inhibition of the motility of third-stage larvae (xL3s) at 24 h, 48 h and 72 h as well as fourth-stage larvae (L4s) at 24 h, 48 h and 72 h for individual compounds (A); and the inhibition of the development of L4s after seven days in vitro culture (B). Each data point represents the mean of three experiments repeated in triplicate on separate days (± standard error of the mean, SEM).

Table 1.

Testing of the effects of the active compound SN00797439 from the Compounds Australia ‘Open Scaffolds’ collection on the motility of exsheathed third-stage larvae (xL3s) as well as the motility and development of fourth-stage larvae (L4s) of Haemonchus contortus. A comparison of ‘half of the maximum inhibitory concentration’ (IC50) values with those of reference anthelmintic compounds (monepantel and moxidectin); expressed as mean IC50 (in μM) ± standard error of the mean or a range.

| Time point | SN00797439 | Monepantel | Moxidectin |

|---|---|---|---|

| xL3 motility | |||

| 24 h | 3.46 ± 0.82 | 0.48 ± 0.23 | 0.19 ± 0.03 |

| 48 h | 10.08 ± 2.06 | 0.26 ± 0.15 | 0.97 ± 0.84 |

| 72 h | 5.93 ± 1.38 | 0.16 ± 0.08 | 0.08 ± 0.04 |

| L4 motility | |||

| 24 h | 6.25 to 12.5 | 0.76 ± 0.29 | 0.07 ± 0.04 |

| 48 h | 0.78 to 1.5 | 0.34 ± 0.18 | 0.05 ± 0.02 |

| 72 h | 0.31 to 0.78 | 0.37 ± 0.32 | 0.02 ± 0.01 |

| L4 development | |||

| 7 days | 11.04 ± 2.16 | 0.075 ± 0.04 | 3.45 ± 0.75 |

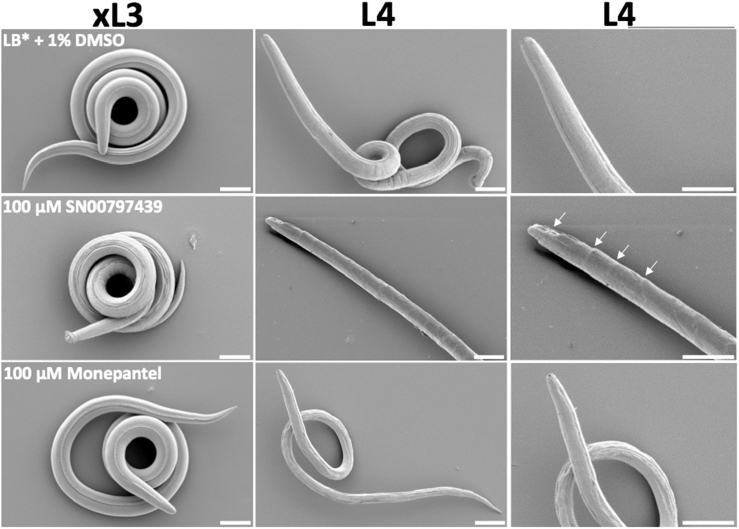

Dose-response curves (two-fold serial dilutions from 100 μM to 0.00076 μM) revealed that SN00797439 inhibited the motility of L4s, with IC50 values of 6.25–12.5 μM (24 h), 0.78–1.5 μM (48 h) and 0.31–0.78 μM (72 h) (Fig. 2; Table 1). Subsequently, SN00797439 was tested for its ability to inhibit growth/development from xL3 to L4. The dose-response curves revealed that this compound inhibited L4 development, with an IC50 value of 11.04 ± 2.16 μM (Fig. 2; Table 1). Upon SEM analysis, SN00797439 caused only minor morphological damage to xL3, but resulted in considerable cuticle alterations to the L4 stage, including multiple, cuticle-‘embossed’ rings around the worm along its length and a ‘scaly’ appearance of the worm surface (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Scanning electron microscopic images of exsheathed third-stage larvae (xL3) and fourth-stage (L4) larvae of Haemonchus contortus following exposure to 100 μM of compound SN00797439, monepantel (positive control) or LB* + 1% DMSO (negative control). Arrows indicate the cuticular alterations observed following treatment with SN00797439. Scale = 20 μM.

3.2. Compound SN00797439 also has inhibitory activity on the motility of different developmental stages of other parasitic nematodes

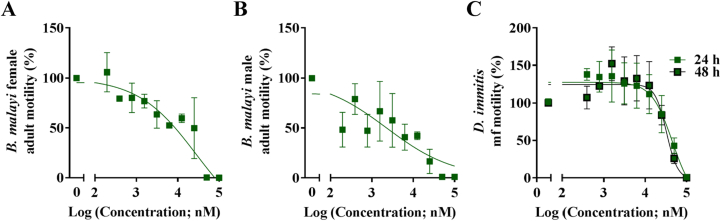

In order to assess whether compound SN00797439 would act against nematodes that are genetically (evolutionarily) very distant from H. contortus (order Strongylida), we tested whether these compounds would inhibit the motility of adults and microfilariae of B. malayi as well as microfilariae of D. immitis in vitro. SN00797439 inhibited the motility of female and male adults of B. malayi (Fig. 4; Table 2), with movement ceasing at 100 μM (24 h) and 50 μM (48 h). This result compares with 1.3 μM (24 h) and 2.9 μM (48 h) for moxidectin (cf. Storey et al., 2014). SN00797439 was then tested for its effect on microfilariae of B. malayi (released from females after 72 h in vitro), and inhibited the motility of the microfilariae, with an IC50 of ∼3 μM (24 h) compared with ∼6 μM for moxidectin (cf. Storey et al., 2014).

Fig. 4.

The inhibitory effect of compound SN00797439 from the Open Scaffolds collection on the motility of female and male adult Brugia malayi at 24 h (panels A and B). The inhibitory effect of compound SN00797439 (C) on Dirofilaria immitis microfilariae (mff) at 24 h and 48 h. Dose-response experiments were performed at 100 μM and serially diluted two-fold. Each data point represents the mean of at least two experiments repeated in duplicate on separate days (± standard error of the mean, SEM).

Table 2.

Testing the effect of compound SN00797439 from the Open Scaffolds collection on the motility of filarial nematodes Brugia malayi and Dirofilaria immitis. Approximate ‘half of the maximum inhibitory concentration’ (IC50) values of individual compounds are indicated.

| Time point | Parasite/stage/sex | SN00797439 IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| Brugia malayi | ||

| 24 h | Adult female | 25 to 50 |

| 24 h | Adult male | 25 to 50 |

| 72 h | Microfilariae | 3 |

| Dirofilaria immits | ||

| 24 h | Microfilariae | 50 |

| 48 h | Microfilariae | 50 |

Subsequently, SN00797439 was tested against microfilariae of D. immitis, a filarial nematode that is related to B. malayi, and inhibited the motility of microfilariae, with complete inhibition at 100 μM (24 h and 48 h). For both of these time points, an IC50 value of ∼50 μM was achieved (Table 2), which compares with IC50 values of 43 μM and 9.3 μM published for ivermectin and moxidectin, respectively (Storey et al., 2014). In addition, when tested on A. ceylanicum and T. muris, SN00797439 killed adult A. ceylanicum at 50 μM and displayed a high nematocidal activity against T. muris L1s (90.1% of L1s dead at 100 μM). The positive-control compound (levamisole) killed both nematode species at the same concentration as used for the test compound. Further work should be conducted to assess the activity of SN00797439 against late larval stages and adults of both D. immitis and T. muris.

3.3. Cytotoxicity and selectivity of SN00797439

Using an established proliferation assay, SN00797439 was assessed for its toxicity on mammary epithelial cells (Table 3) and was shown to be selective for parasitic larvae of H. contortus, with a selectivity index (SI) of ∼9–128, compared with ∼67–332 (monepantel) and ∼2 to 300 (moxidectin) for the positive-control compounds (Table 3). For filarial worms, SN00797439 was selective only for microfilariae of B. malayi (but not D. immitis) with an SI of 33.3.

Table 3.

Cytotoxicity of compound SN00797439 on a normal mammary epithelial cell line (MCF10A) and selectivity of these compounds on Haemonchus contortus exsheathed third-stage larvae (xL3) and fourth-stage larvae (L4), Dirofilaria immitis microfilariae (mff) and Brugia malayi mff and adult filarial worms. Selectivity indices (SIs) were calculated using a recognised formula; (SI = ‘half of the maximum inhibitory concentration’ (IC50) for MCF10A cells/IC50 for nematode).

| Compound | MCF10A cells |

Selectivity index (SI)a |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

H. contortus |

Filarioids |

||||||||

| IC50 (μM) | % inhibition at 100 μMc | xL3 (72 h) |

L4 development (7 days) |

L4 (72 h) |

B. malayi adult females |

B. malayi adult males |

B. malayi mff |

D. immitis mff (48 h) |

|

| SN00797439 | 50–100 | 6.20 ± 0.66 | 16.9 | 9.1 | 128.2b | 2b | 2b | 33.33b | 2b |

| Monepantel | 24.93 ± 11.83 | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 115.8 | 332.4 | 67.4 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Moxidectin | <6 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 75 | 1.7 | 300 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

4. Conclusion

In the past three decades, only four ‘new’ anthelmintic drugs, emodepside (Martin et al., 2012, Harder, 2016), tribendimidine (Xiao et al., 2005, Steinmann et al., 2008), monepantel (Kaminsky et al., 2008, Prichard and Geary, 2008) and derquantel (Little et al., 2011), have been commercialised. Due to the rapid emergence of anthelmintic resistance, even to some recently commercialised compounds (Scott et al., 2013, Van den Brom et al., 2015, Sales and Love, 2016, Cintra et al., 2016), there is a need to identify, validate, optimise and develop novel chemical entities for the treatment of parasitic worms of humans and agricultural animals (Geary et al., 2015).

With this focus in mind, we screened 14,464 prioritised compounds (representing a collection of 33,999 chemicals) to identify potential starting points for the design of new anthelmintics. Under the conditions used in this screening platform, compound SN00797439 was identified as a hit, and exhibited considerable anthelmintic activity against H. contortus and induced a “coiled” phenotype (Supplementary File 2). SN00797439 was also shown to have anthelmintic activity against a species of hookworm (A. ceylanicum; order Strongylida) and two filarioid nematodes (D. immitis and B. malayi; order Spirurida). Additionally, this compound was also shown to have activity against the mouse whipworm, T. muris, which is used as a model to study the genetically related human whipworm (T. trichiura; order Enoplida) (cf. Foth et al., 2014) These findings, for multiple representatives of taxonomically, biologically and genetically distinct orders (i.e. Strongylida vs. Spirurida vs. Enoplida), indicate a relatively broad spectrum of in vitro activity of this chemotype against nematodes.

Compound SN00797439 is made up of an oxadiazole and pyrrolidine core. An appraisal of the intellectual property surrounding the sub-structures of this compound (Li and Zhong, 2011, Li and Zhong, 2010) reveals that similar compounds have been explored as therapeutics for the control of hepatitis C, but not yet as anthelmintics. Following the identification of SN00797439 in the primary screen against H. contortus, an evaluation revealed differences in its potency to inhibit the motility, growth and/or development of the parasitic larval stages of this nematode. The results showed that SN00797439 was more potent on L4s than xL3s. This difference in potency might be due to variation in expression of its target(s) in the nematode, a distinction in physiology between these two developmental stages of the worm and/or the nature and extent of the uptake of the compound by the worm. An integrated use of transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic techniques (Mikami et al., 2012, Schwarz et al., 2013, Preston et al., 2016c) might be able to elucidate the physiological and biological pathways in H. contortus and/or other worms affected by SN00797439.

The route from discovery to development and then to the market of a new anthelmintic is a long one, requiring a serious commitment in terms of time, effort and funding. In this present study, we identified a new hit compound with activity against biologically and genetically distinct nematodes. The novel and rather unexplored chemical scaffold of the hit compound as well as the observed broad activity make this compound a starting point for designing and optimising new chemotherapeutics. Thus, we are now eager to critically assess the activity of SN00797439 on key developmental stages of a range of parasitic nematodes of humans, including Ascaris sp. (large roundworm) and other common species of hookworm (Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale) as well as additional filarial worms (Onchocerca volvulus and Loa Loa) which cause some of the most neglected tropical diseases and collectively affect ∼ 1.8 billion people, resulting in a loss of 8.5 million DALYs worldwide (e.g., Hotez et al., 2016). Importantly, substantial future work also needs to focus on (i) studying the structure-activity relationship (SAR) of derivatives of compounds SN00797439 via medicinal chemistry optimization, to attain a new entity with broad-spectrum and enhanced activity against key nematode stages; (ii) on assessing the pharmacological properties (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity; ADMET) of the most promising compound series; and ultimately (iii) on evaluating anthelmintic efficacy and safety of active compounds in vivo in animals.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest of any of the authors of this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The present study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC), the Australian Research Council (ARC) and the Wellcome Trust (RBG), and supported by a Victoria Life Sciences Computation Initiative, Australia (VLSCI; grant no. VR0007) on its Peak Computing Facility at The University of Melbourne, Australia, an initiative of the Victorian Government, Australia. Animal ethics approval (AEC no. 0707258) was granted by The University of Melbourne. We thank our colleagues at Medicines for Malaria Ventures (MMV) for their support. We expressly wish to acknowledge the efforts of the constructors of the 'Open Scaffold' library at Compounds Australia, David Camp, Graeme Stevenson, Mikhail Krasavin and Alain-Dominique Gorse. The Victorian Centre for Functional Genomics (KJS) is supported by funding from the Australian Government's Education Investment Fund through the Super Science Initiative and the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre Foundation. We thank an anonymous reviewer for constructive comments and suggestions on our manuscript.

Footnotes

In appreciation of the efforts of David Camp, Graeme Stevenson, Mikhail Krasavin, Alain-Dominique Gorse and other colleagues for originally assembling and maintaining the 'Open Scaffolds' collection.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpddr.2017.05.004.

Contributor Information

Abdul Jabbar, Email: jabbara@unimelb.edu.au.

Robin B. Gasser, Email: robinbg@unimelb.edu.au.

Appendix B. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

Physicochemical properties of chemicals compounds in the Open Scaffolds collection screened against exsheathed third-stage larvae (xL3s) of Haemonchus contortus.

References

- Baell J.B. Feeling nature's PAINs: natural products, natural product drugs, and pan assay interference compounds (PAINs) J. Nat. Prod. 2016;79:616–628. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baell J.B., Holloway G.A. New substructure filters for removal of pan assay interference compounds (PAINs) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:2719–2740. doi: 10.1021/jm901137j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell W.C. Lessons from the history of ivermectin and other antiparasitic agents. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2016;4:1–14. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-021815-111209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cintra M.C., Teixeira V.N., Nascimento L.V., Sotomaior C.S. Lack of efficacy of monepantel against Trichostrongylus colubriformis in sheep in Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2016;216:4–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick A. The global burden of neglected tropical diseases. Public Health. 2012;126:233–236. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick J.L. Global food security: the impact of veterinary parasites and parasitologists. Vet. Parasitol. 2013;195:233–248. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foth B.J., Tsai I.J., Reid A.J., Bancroft A.J., Nichol S., Tracey A., Holroyd N., Cotton J.A., Stanley E.J., Zarowiecki M., Liu J.Z., Huckvale T., Cooper P.J., Grencis R.K., Berriman M.L. Whipworm genome and dual-species transcriptome analyses provide molecular insights into an intimate host-parasite interaction. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:693–702. doi: 10.1038/ng.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geary T.G., Sakanari J.A., Caffrey C.R. Anthelmintic drug discovery: into the future. J. Parasitol. 2015;101:125–133. doi: 10.1645/14-703.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder A. The biochemistry of Haemonchus contortus and other parasitic nematodes. Adv. Parasitol. 2016;93:69–94. doi: 10.1016/bs.apar.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homer R.W., Swanson J., Jilek R.J., Hurst T., Clark R.D. SYBYL line notation (SLN): a single notation to represent chemical structures, queries, reactions, and virtual libraries. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2008;48:2294–2307. doi: 10.1021/ci7004687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotez P.J., Bottazzi M.E., Strych U. New vaccines for the world's poorest people. Annu. Rev. Med. 2016;67:405–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-051214-024241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotez P.J., Alvarado M., Basáñez M.G., Bolliger I., Bourne R., Boussinesq M., Brooker S.J., Brown A.S., Buckle G., Budke C.M., Carabin H., Coffeng L.E., Fèvre E.M., Fürst T., Halasa Y.A., Jasrasaria R., Johns N.E., Keiser J., King C.H., Lozano R., Murdoch M.E., O'Hanlon S., Pion S.D.S., Pullan R.L., Ramaiah K.D., Roberts T., Shepard D.S., Smith J.L., Stolk W.A., Undurraga E.A., Utzinger J., Wang M., Murray C.J.L., Naghavi M. The global burden of disease study 2010: interpretation and implications for the neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014;8:e2865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan R.M., Vidyashankar A.N. An inconvenient truth: global worming and anthelmintic resistance. Vet. Parasitol. 2012;186:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminsky R., Ducray P., Jung M., Clover R., Rufener L., Bouvier J., Wenger A., Schroeder F., Desaules Y., Hotz R., Goebel T., Hosking B.C., Pautrat F., Wieland-Berghausen S., Ducray P. A new class of anthelmintics effective against drug-resistant nematodes. Nature. 2008;452:176–180. doi: 10.1038/nature06722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox M.R., Besier R.B., Le Jambre L.F., Kaplan R.M., Torres-Acosta J.F., Miller J., Sutherland J. Novel approaches for the control of helminth parasites of livestock VI: summary of discussions and conclusions. Vet. Parasitol. 2012;186:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotze A.C., Prichard R.K. Anthelmintic resistance in Haemonchus contortus: history, mechanisms and diagnosis. Adv. Parasitol. 2016;93:397–428. doi: 10.1016/bs.apar.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumarasingha R., Preston S., Yeo T.C., Lim D.S.L., Tu C.L., Palombo E.A., Shaw J.M., Gasser R.B., Boag P.R. Anthelmintic activity of selected ethno-medicinal plant extracts on parasitic stages of Haemonchus contortus. Parasit. Vectors. 2016;9:187. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1458-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane J., Jubb T., Shephard R., Webb-Ware J., Fordyce G. 2015. MLA Final Report: Priority List of Endemic Diseases for the Red Meat Industries. MLA.www.mla.com.au/download/finalreports?itemId=2877 Available from: Accessed 7th September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Zhong M. 2011. Preparation of Biarylacetylenes, Arheteroarylacetylenes and Biheteroarylacetylenes End-capped with Amino Acid or Peptide Derivatives as Inhibitors of HCV NS5A. Patent WO 2011150243 A1 20111201. [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Zhong M. 2010. Preparation of Biarylacetylenes, Arheteroarylacetylenes and Biheteroarylacetylenes End-capped with Amino Acid or Peptide Derivatives as IInhibitors of HCV NS5A. Patent WO 2010065668 A1 20100610. [Google Scholar]

- Little P.R., Hodge A., Maeder S.J., Wirtherle N.C., Nicholas D.R., Cox G.G., Conder G.A. Efficacy of a combined oral formulation of derquantel–abamectin against the adult and larval stages of nematodes in sheep, including anthelmintic-resistant strains. Vet. Parasitol. 2011;181:180–193. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R.J., Buxton S.K., Neveu C., Charvet C.L., Robertson A.P. Emodepside and SL0-1 potassium channels: a review. Exp. Parasitol. 2012;132:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalski M.L., Griffiths K.G., Williams S.A., Kaplan R.M., Moorhead A.R. The NIH-NIAID filariasis research reagent resource center. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011;5:e1261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami T., Aoki M., Kimura T. The application of mass spectrometry to proteomics and metabolomics in biomarker discovery and drug development. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2012;5:301–316. doi: 10.2174/1874467211205020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutafchiev Y., Bain O., Williams Z., McCall J.W., Michalski M.L. Intraperitoneal development of the filarial nematode Brugia malayi in the Mongolian jird (Meriones unguiculatus) Parasitol. Res. 2014;113:1827–18235. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3829-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston S., Jabbar A., Gasser R.B. A perspective on genomic-guided anthelmintic discovery and repurposing using Haemonchus contortus. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016;40:368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston S., Jabbar A., Nowell C., Joachim A., Ruttkowski B., Baell J., Cardno T., Korhonen P.K., Piedrafita D., Ansell B.R., Jex A.R., Hofmann A., Gasser R.B. Low cost whole-organism screening of compounds for anthelmintic activity. Int. J. Parasitol. 2015;45:333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston S., Jabbar A., Nowell C., Joachim A., Ruttkowski B., Cardno T., Hofmann A., Gasser R.B. Practical and low cost whole-organism motility assay: a step-by-step protocol. Mol. Cell. Probes. 2016;30:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston S., Luo J., Zhang Y., Jabbar A., Crawford S., Baell J., Hofmann A., Hu M., Zhou H.B., Gasser R.B. Selenophene and thiophene-core estrogen receptor ligands that inhibit motility and development of parasitic stages of Haemonchus contortus. Parasit. Vectors. 2016;9:346. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1612-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prichard R.K., Geary T.G. Drug discovery: fresh hope to can the worms. Nature. 2008;452:157–158. doi: 10.1038/452157a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeber F., Jex A.R., Gasser R.B. Impact of gastrointestinal parasitic nematodes of sheep, and the role of advanced molecular tools for exploring epidemiology and drug resistance - an Australian perspective. Parasit. Vectors. 2013;6:153. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales N., Love S. Resistance of Haemonchus sp. to monepantel and reduced efficacy of a derquantel abamectin combination confirmed in sheep in NSW, Australia. Vet. Parasitol. 2016;15:193–196. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz E.M., Korhonen P.K., Campbell B.E., Young N.D., Jex A.R., Jabbar A., Hall R.S., Mondal A., Howe A.C., Pell J., Hofmann A., Boag P.R., Zhu X.Q., Gregory T., Loukas A., Williams B.A., Antoshechkin I., Brown C., Sternberg P.W., Gasser R.B. The genome and developmental transcriptome of the strongylid nematode Haemonchus contortus. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R89. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-8-r89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott I., Pomroy W.E., Kenyon P.R., Smith G., Adlington B., Moss A. Lack of efficacy of monepantel against Teladorsagia circumcincta and Trichostrongylus colubriformis. Vet. Parasitol. 2013;198:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson M., Poulsen S.A. An overview of Australia's compound management facility: the Queensland Compound Library. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014;9:28–33. doi: 10.1021/cb400912x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommerville R.I. The development of Haemonchus contortus to the fourth stage in vitro. J. Parasitol. 1966;52:127–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann P., Zhou X.N., Du Z.W., Jiang J.Y., Xiao S.H., Wu Z.X., Zhou H., Utzinger J. Tribendimidine and albendazole for treating soil-transmitted helminths, Strongyloides stercoralis and Taenia spp.: open-label randomized trial. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2008;2:e322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey B., Marcellino C., Miller M., Maclean M., Mostafa E., Howell S., Sakanari J., Wolstenholme A., Kaplan R. Utilization of computer processed high definition video imaging for measuring motility of microscopic nematode stages on a quantitative scale: “The Worminator”. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2014;4:233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Brom R., Moll L., Kappert C., Vellema P. Haemonchus contortus resistance to monepantel in sheep. Vet. Parasitol. 2015;209:278–280. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolstenholme A.J., Kaplan R.M. Resistance to macrocyclic lactones. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2012;13:873–887. doi: 10.2174/138920112800399239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S.H., Hui-Ming W., Tanner M., Utzinger J., Chong W. Tribendimidine: a promising, safe and broad-spectrum anthelmintic agent from China. Acta Trop. 2005;94:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Five-second digital movies of live exsheathed third-stage larvae exposed to 20 μM of SN00797439 and 20 μM of each of the two positive-control compounds (i.e. monepantel and moxidectin); the negative control (LB* + 0.5% DMSO) does not contain compound.

Physicochemical properties of chemicals compounds in the Open Scaffolds collection screened against exsheathed third-stage larvae (xL3s) of Haemonchus contortus.