Introduction

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN) was defined in the 2008 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissue as a malignant proliferation of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cells.1 The skin lesions appear as bruiselike erythematous nodules or tumors and are usually found already at presentation. BPDCN is highly malignant, with a mean survival time of 15.2 months.2 Data are limited concerning patients with localized skin-limited BPDCN (LS-BPDCN).

We report our experience with 2 patients with LS-BPDCN, both of whom achieved potential cure with hyper-CVAD chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone) followed by consolidative localized radiotherapy (LRT), without hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).

Case descriptions

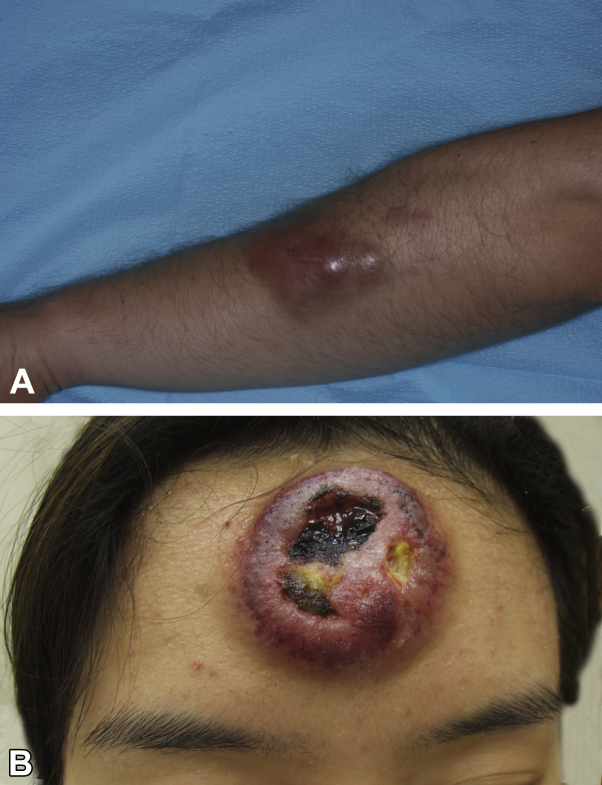

The first patient was a 38-year-old white man and the second was a 23-year-old Asian woman. Sites of occurrence were the forearm (patient 1; Fig 1, A) and forehead (patient 2; Fig 1, B). In both cases, the lesion started as a solitary papule/plaque. The forehead lesion was initially diagnosed clinically as a pimple. The lesions enlarged within weeks to months to form tumors (largest diameter, 6-8 cm) with a dusky, purplish/violet, or bruiselike appearance; in one case, the lesion was ulcerated (Fig 1, B). The patients had no systemic complaints. No lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly was noted on examination.

Fig 1.

LS-BPDCN lesion pretreatment. A, Patient 1. Well-demarcated erythematous tumor, adjacent to a small infiltrated plaque, observed on the forearm. B, Patient 2. Bulky tumor mass on the forehead with ulceration.

Complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic profile, and serum lactate dehydrogenase level were within normal range. Findings on bone marrow biopsy, whole-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography were unremarkable.

Histopathologic findings were remarkable for a dense dermis-based monomorphous infiltrate composed of blast cells with irregular nuclei and 1 to several small nucleoli, without epidermal involvement. Cells in patient 1 were positive for CD4, CD56, CD123, TCL-1, CD2, CD7, and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-1 and negative for CD3, CD8, CD5, CD30, CD20, CD34, myeloperoxidase, and Epstein-Barr virus (in situ hybridization).

In patient 2, cells were positive for CD4, CD56, CD123, CD43, CD68, and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-1 and negative for CD3, CD8, CD20, CD30, CD117, myeloperoxidase, and Epstein-Barr virus (in situ hybridization).

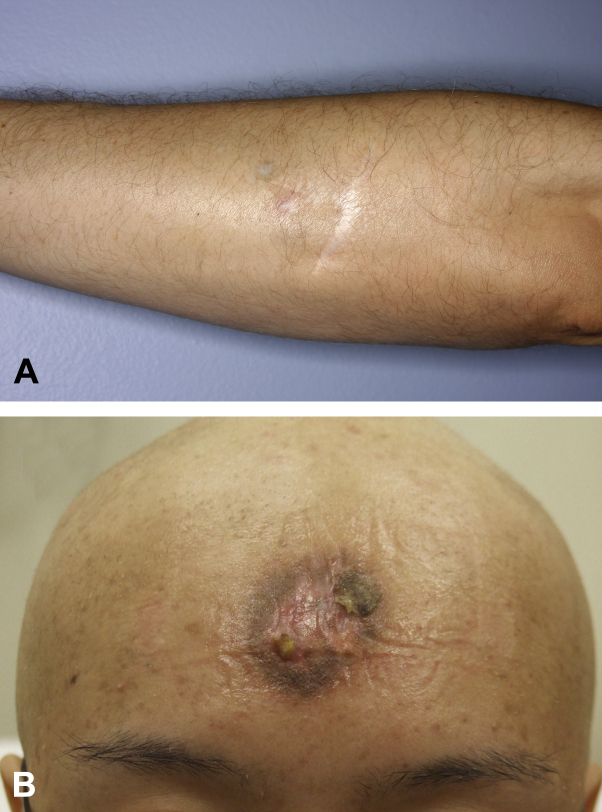

Both patients were treated with combination chemotherapy, completing 4 cycles of hyper-CVAD, alternating with methotrexate and cytarabine (A+B). One month after chemotherapy, both underwent consolidative LRT (36 Gy). Clinical remission was achieved (Fig 2, A and B) and has been sustained so far for 6 years (patient 1) and 9 years (patient 2), without HSCT.

Fig 2.

LS-BPDCN lesion after treatment. A and B, After treatment with hyper-CVAD × 4 cycles and consolidative LRT; only a residual scar remains.

Discussion

Only 19 patients with LS-BPDCN have been reported in the literature since the latest classification of BPDCN in 2008,3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 (their data are summarized in Table I). Median age of the reported patients at presentation was 46 years (range, 5-83), which is younger than the median age documented for all patients with BPDCN (67.8 years).2 None of the reports mentioned time to diagnosis from initial evaluation by a clinician. In our patient 2, the diagnosis was delayed by 5 months, suggesting that LS-BPDCN is not always recognized by clinicians at presentation. A delay in diagnosis poses a risk of disease progression.

Table I.

Localized skin-limited blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: current study and review of cases reported since 2008

| Author (year)/no. of patients | Sex/age at dx (y) | Time to dx from symptom onset/from initial evaluation by a clinician (mo) | Lesion location/morphology/size (cm) | Initial treatment and response | Relapse-free survival (mo)/therapy at relapse | Transplant | Overall survival (mo) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaune et al.3 2009/1 | F/66 | 12/NS | Inner ankle/violaceous tumor | 3 cycles of cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunomycin, vincristine, prednisone + RT (34 Gy)-PR | NS/6 weeks after completion of chemotherapy PD in skin, paranasal sinus and LN. Received 2 followed by 3 cycles of liposomal doxorubicin – NR. One month later, fulminant leukemia, treated with etoposide combined with fludarabine/cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone | No | 14 | DOD |

| Dalle et al.4 2010/9 | M/37 | NS | Leg/nodule | Lomustine, doxorubicin, cytarabine-PR | 3/ifosfamide, etoposide, cytarabine, MTX | Allo-SCT | 54 | DCD |

| M/70 | Cheek/nodule | Cytarabine, idarubicin, lomustine-PD | PD/Mini-CHA | No | 19 | DCD | ||

| M/73 | Shoulder/nodule | RT-PD | PD/Idarubicin, cytarabine, lomustine | No | 36 | DCD | ||

| M/75 | Arm/nodule | Refused treatment | NS | No | 12 | DCD | ||

| M/83 | Cheek/nodule | RT-CR | 8/Refused treatment | No | 8 | Alive | ||

| F/25 | Leg/tumor | Hyper-CVAD-CR | 6/Autologous BMT | Autologous BMT | 38 | Alive | ||

| M/82 | Scalp/tumor | RT-CR | 9/Etoposide | No | 19 | DCD | ||

| M/78 | Leg/tumor | CHOP-CR | 12/NS | No | 12 | Alive | ||

| F/60 | Cheek/nodule | MTX, asparaginase, RT-CR | NS | No | 11 | LTF | ||

| Dohm et al.5 2011/1 | M/32 | NS | Arm/nodule/6 × 4 | CHOEP-14 × 6, +RT (36 Gy) – CR | 11/First relapse: 4 cycles of ifosfamide, carboplatin and etoposide + RT (36 Gy): Second relapse: 4 cycles of fludarabine and cyclophosphamide. Consolidating allo-SCT. Third relapse: RT | Allo-SCT | 66 | DOD |

| Hashikawa et al.6 2012/2 | M/46 | NS | Arm/nodule/2 | AML-type-PD | PD | No | 1 | DOD |

| F/5 | NS | Arm | ALL-type-CR | No relapse during follow-up | No | 12 | Alive | |

| Tsunoda et al.7 2012/1 | M/74 | 0.5/immediate diagnosis | Postauricular region/red skin tumor/3.6 × 1.9 | RT (27 Gy)-CR | 2/AdVP | No | NS | DOD |

| An et al.8 2013/1 | F/18 | NS | Thigh/nodule | VPDL-CR | No relapse during follow-up | No | 18 | Alive |

| Sugimoto et al.9 2013/1 | M/74 | At least 6/3 | Shoulder/soft, erythematous mass with vessel dilatation, irreg. borders/5 × 3 | 2/3-dose DeVIC+RT-CR | No relapse during follow-up | No | 12 | NED |

| Heinicke et al.10 2015/1 | F/62 | 6/NS | Lower leg/papule surrounded by diffuse erythema | Vincristine and prednisolone, then CHOP ×6+RT (40 Gy)-CR | 4/1 cycle of FLAG-Ida, 1 cycle of MTX, asparaginase, high-dose cytarabine-CR | Allo-SCT | 41 from initial diagnosis | NED |

| Nomura et al.11 2015/1 | F/7 | 5/NS | Forearm/purplish macule/4.6 × 2.6 | Vincristine, prednisolone, cyclophosphamide, daunorubicin and L-asparaginase-CR | No relapse during follow-up. Received early intensification phase, a prophylaxis phase for the CNS, and a re-induction phase-CR. Maintenance therapy with MTX and 6-mercaptopurine | No | 12 (from beginning of therapy) | NED |

| Sheng et al.12 2015/1 | F/6 | 4/NS | Temple/red infiltrated plaques/1-2 | Topical Chinese medicine | NR | No | 16 | DOD |

| Present report, 2016/2 | Pt. 1 M/38 |

3/immediate diagnosis | Forearm/dusky, purple-colored plaque/5 × 6 | Hyper-CVAD (A+B)+RT (36Gy)-CR | No relapse during follow-up | No | 72 | NED |

| Pt. 2 F/23 |

7/5 | Forehead/bulky, violet-colored, ulcerated tumor/7 × 8 | Hyper-CVAD (A+B)+RT (36Gy)-CR | No relapse during follow-up | No | 108 | NED |

AdVP, Adriamycin/vincristine/prednisone; Allo-SCT, allogeneic stem cell transplantation; BMT, bone marrow transplantation; CHA, mitoxantrone, cytarabine; CHOP, cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine, and prednisone; CR, complete response; DCD, decreases, could be dead; DeVIC, dexamethasone, VP16, ifosfamide, carboplatin; DOD, died of disease; dx, diagnosis; FLAG-Ida, fludarabine, cytarabine, idarubicin, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; LF, lost to follow-up; LN, lymph nodes; MTX, methotrexate; NED, no evidence of disease; NR, no response; NS, not stated; OS, overall survival; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; RFS, relapse-free survival; RT, radiation therapy; VPDL, vincristine, methylprednisolone, daunorubicin, L-asparaginase.

In 15 of the total 21 patients with LS-BPDCN (current work and the literature, 71%), the lesion was located on the upper part of the body. It was clinically described as a violaceous, bruiselike erythematous nodule/tumor.

There is no established standard frontline treatment for BPDCN. Some evidence supports the use of an acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)-like protocol (eg, hyper-CVAD) over acute myelogenous leukemia–like protocols.13 Current active clinical trials are exploring novel treatments including targeted therapies (SL-401, XmAb14045) and genetically modified T-cell immunotherapy. Promising results have been reported for SL-401, a diphtheria toxin conjugated to interleukin-3, directed to the interleukin-3 receptor (CD123), a target overexpressed on BPDCN. According to the preliminary results of a phase 2 registration clinical trial in patients with BPDCN, SL-401 showed robust single-agent activity, including 100% overall response rate in first-line patients and 87% in all lines, with multiple complete responses; response duration data are being processed and are so far encouraging (presented at the 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology and American Society of Hematology Annual Meetings, NCT02113982).

A study of the benefit of HSCT showed that the difference in mean overall survival time between those who underwent transplantation (9 allogeneic [allo], 1 autologous) and those who did not was highly significant (31.3 vs 12.8 months; P = .0018).4

Less information is available on the optimal therapeutic approach to LS-BPDCN specifically. Table I lists the treatments used in the 19 patients previously reported in the literature. Conclusions are difficult to reach because the chemotherapy protocols were not uniform, and not all patients received additional LRT. Furthermore, there are almost no data on the role of HSCT in LS-BPDCN. If we extrapolate from the limited experience with isolated myeloid sarcoma, we may conclude that allo-HSCT may not be the best first-line therapy.14 Of the total 21 patients with LS-BPDCN (current report and the literature), 4 underwent HSCT (3 allo-HSCT, 1 auto-HSCT), of whom, 2 died (1 of the disease; in 1 the cause of death was not reported). Thus, the benefit of HSCT in LS-BPDCN is unclear. Both patients presented here showed disease regression without HSCT.

Overall, prognostic data are available for 18 of 19 patients with LS-BPDCN reported in the literature. Median duration of follow-up was 16 months (range, 1-66), and 10 patients died of the disease. In contrast, both our patients achieved potential cure during follow-up of 6 and 9 years. Both were treated with ALL-like (hyper-CVAD, A+B) chemotherapy protocol and consolidative LRT. To our knowledge, there are no reports specifically addressing the use of this protocol as the initial treatment for primary LS-BPDCN. Beyond treatment type, it is possible that the long-term response of our patients may be attributable partly to yet undefined but different biological activity/characteristics of LS-BPDCN tumors.

To prevent a delay in diagnosis, clinicians should be aware of the appearance of primary LS-BPDCN at presentation, mainly as a violaceus, bruiselike, infiltrated plaque or tumor, usually on the upper part of the body. According to our experience, in age-appropriate cases of LS-BPDCN, initial treatment with aggressive combination chemotherapy, with some evidence supporting ALL-like regimens, followed by consolidation with LRT, even without HSCT, may achieve long-lasting remissions if not cure.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

This study was presented at the EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force Meeting, September 2015, Turin, Italy.

References

- 1.Facchetti F., Jones D.M., Petrella T. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. In: Swerdlow S.H., Campo Harris N.L., Jaffe E.S., editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2008. pp. 145–147. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Julia F., Dalle S., Duru G. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasms: clinico-immunohistochemical correlations in a series of 91 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:673–680. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaune K.M., Baumgart M., Bertsch H.P. Solitary cutaneous nodule of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm progressing to overt leukemia cutis after chemotherapy: immunohistology and FISH analysis confirmed the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:695–701. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181a5e13d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalle S., Beylot-Barry M., Bagot M. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: is transplantation the treatment of choice? Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:74–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dohm A., Hasenkamp J., Bertsch H.P. Progression of a CD4+/CD56+ blastic plasmacytoid DC neoplasm after initiation of extracorporeal photopheresis in an allogeneic transplant recipient. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2011;46:899–900. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashikawa K., Niino D., Yasumoto S. Clinicopathological features and prognostic significance of CXCL12 in blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:278–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsunoda K., Satoh T., Akasaka K. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: report of two cases. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2012;52:23–29. doi: 10.3960/jslrt.52.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.An H.J., Yoon D.H., Kim S. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: a single-center experience. Ann Hematol. 2013;92:351–356. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1614-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugimoto K., Shimada A., Yamaguchi N. Sustained complete remission of a limited-stage blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm followed by a simultaneous combination of low-dose DeVIC therapy and radiation therapy: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:2603–2608. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinicke T., Hütten H., Kalinski T. Sustained remission of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm after unrelated allogeneic stem cell transplantation-a single center experience. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:283–287. doi: 10.1007/s00277-014-2193-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nomura H., Egami S., Kasai H. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm in a 7-year-old girl with a solitary skin lesion mimicking traumatic purpura. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:231–232. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheng N., Xiong J.S., Wang Y.H. Infiltrative plaques on the temple. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:283–284. doi: 10.1111/pde.12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsagarakis N.J., Kentrou N.A., Papadimitriou K.A. Hellenic Dendritic Cell Leukemia Study Group: Acute lymphoplasmacytoid dendritic cell (DC2) leukemia: results from the Hellenic Dendritic Cell Leukemia Study Group. Leuk Res. 2010;34:438–446. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson C.S., Medeiros L.J. Extramedullary manifestations of myeloid neoplasms. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;144:219–239. doi: 10.1309/AJCPO58YWIBUBESX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]