Abstract

Background

Few studies have investigated the impact of obesity on the response to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) in patients with axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA). The aim of our study was to investigate the impact of different body mass index (BMI) categories on TNFi response in a large cohort of patients with axSpA.

Methods

Patients with axSpA within the Swiss Clinical Quality Management (SCQM) program were included in the current study if they fulfilled the Assessment in Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) criteria for axSpA, started a first TNFi after recruitment, and had available BMI data as well as a baseline and follow-up visit at 1 year (±6 months). Patients were categorized according to BMI: normal (BMI 18.5 to <25), overweight (BMI 25–30), and obese (BMI >30). We evaluated the proportion of patients achieving the 40% improvement in ASAS criteria (ASAS40), as well as Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) improvement and status scores at 1 year. Patients having discontinued the TNFi were considered nonresponders. We controlled for age, sex, HLA-B27, axSpA type, BASDAI, BASMI, elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), current smoking, enthesitis, physical exercise, and co-medication with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, as well as with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in multiple adjusted logistic regression analyses.

Results

A total of 624 axSpA patients starting a first TNFi were considered in the current study (332 patients of normal weight, 204 patients with overweight, and 88 obese patients). Obese individuals were older, had higher BASDAI levels, and had a more important impairment of physical function in comparison to patients of normal weight, while ASDAS and CRP levels were comparable between the three BMI groups. An ASAS40 response was reached by 44%, 34%, and 29% of patients of normal weight, overweight, and obesity, respectively (overall p = 0.02). Significantly lower odds ratios (ORs) for achieving ASAS40 response were found in adjusted analyses in obese patients versus patients with normal BMI (OR 0.27, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.09–0.70). The respective adjusted ASAS40 OR in overweight versus normal weight patients was 0.62 (95% CI 0.24–1.14). Comparable results were found for the other outcomes assessed.

Conclusions

Obesity is associated with significantly lower response rates to TNFi in patients with axSpA.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13075-017-1372-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Axial spondyloarthritis, Ankylosing spondylitis, Obesity, TNF inhibition

Background

While the association of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with obesity is established [1, 2], few studies have investigated the issue of obesity in patients with predominantly axial involvement of spondyloarthritis (axSpA), and particularly ankylosing spondylitis (AS). In a small study of 46 patients with AS, an increased body mass index (BMI) was associated with a greater disease activity and functional limitation, as assessed by the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity and Functional Indices (BASDAI and BASFI, respectively) [3]. These findings were confirmed in a larger cohort of 461 axSpA patients from the Netherlands [4].

Obese patients with psoriatic arthritis have been shown to have a lower probability of obtaining minimal disease activity either in the absence of systemic immunosuppressive treatment or upon treatment with conventional or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) [5, 6]. However, with regard to AS patients, the impact of a high BMI on the response to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) has only been formally demonstrated for infliximab in two retrospective studies [7, 8]. The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of BMI on the response to TNFi in a large cohort of patients with axSpA.

Methods

Study population

The Swiss Clinical Quality Management (SCQM) rheumatologists established an ongoing cohort of patients diagnosed with axSpA in 2004 [9]. Assessments at baseline and annual visits are performed according to the recommendations of the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) [10]. We included patients in the current study if they fulfilled the 2009 ASAS criteria for axSpA [11], if they had started treatment with a first TNFi after recruitment, and had baseline BMI data (visit allowed 0–3 months before treatment start) and a follow-up visit at 1 year (±6 months). Patients were categorized according to BMI to the following groups: normal (BMI 18.5 to <25), overweight (BMI 25–30), and obese (BMI >30). As measured height is influenced by kyphosis in advanced disease, corrected height values were calculated by means of geometry using the measurements of the occiput-to-wall distance (see Additional file 1: Figure S1 and Additional file 2: Figure S2).

We excluded patients with concurrent fibromyalgia (as indicated by the treating rheumatologist in the comorbidity questionnaire; n = 25) and patients with a BMI <18.5 (n = 18). The study was approved by the Ethics Commission of the Canton of Zurich. All patients provided written informed consent.

Response to treatment with a first TNF inhibitor

Response to anti-TNF treatment was assessed at 1 year (±6 months). Patients having discontinued treatment were considered as nonresponders [12]. The primary outcome was the achievement of the 40% improvement in ASAS criteria (ASAS40) [10]. The following additional effectiveness measures were evaluated: the ASAS criteria for partial remission (ASAS-PR), a 50% reduction in the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI-50), the proportion of patients achieving an Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) <2.1 (reflecting moderate disease activity) or ASDAS <1.3 (corresponding to inactive disease), as well as a clinically important improvement in ASDAS (change of ≥1.1 between baseline and follow-up) or a major improvement in ASDAS (change of ≥2.0) [13]. Drug retention was assessed as a further secondary outcome. Treatment courses ongoing at the end of the study were censored at the last visit registered in SCQM.

Statistical analysis

We compared baseline characteristics between different BMI categories using the Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables. The significance of differences in crude response rates at 1 year was assessed using the Fisher’s exact test. Logistic regression analysis was used to estimate an adjusted ratio for ASAS40, ASAS-PR, BASDAI-50, ASDAS clinically important or major improvement, and ASDAS status scores <2.1 and <1.3 with adjustment for the following parameters: age, gender, BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Mobility Index (BASMI), human leucocyte antigen-B27 (HLA-B27), classification as nonradiographic axSpA (nr-axSpA) vs. AS, elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) status, physical exercise (yes/no), and current smoking. We tested for interaction between the use of infliximab and BMI categories. Drug maintenance was evaluated with Kaplan-Meier plots and log-rank test, as well as with multiple adjusted Cox proportional hazards models to estimate a covariate-adjusted effect of BMI categories. The same covariates were used in this model as in the response analysis (see above). R statistical software was used for all analyses.

Results

A total of 624 patients had started a first TNFi after recruitment into SCQM and fulfilled the inclusion criteria (normal weight in 332 patients (53%), overweight in 204 patients (33%), and obesity in 88 patients (14%)). Baseline characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. Obese individuals were older, had higher BASDAI and Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score (MASES) levels, and a more important impairment of physical function in comparison to patients of normal weight. There were no significant differences between the BMI categories with regard to the ASDAS, as well as regarding the proportion of patients with elevated CRP, peripheral arthritis, and extraskeletal manifestations. The use of individual biologics as a first TNFi was also similarly distributed. The proportion of patients treated with infliximab, which in contrast to the other anti-TNF agents is dosed in a weight-dependent manner, was similar for the different BMI categories (22%, 20%, and 25% for normal weight, overweight, and obesity, respectively; overall p = 0.57). One year after TNFi initiation, mean BASDAI (±SD) decreased from 5.3 ± 2.0 to 2.9 ± 2.2 in normal weight patients, from 5.6 ± 1.9 to 3.2 ± 2.2 in overweight patients, and from 6.1 ± 1.7 to 4.1 ± 2.4 in obese patients. While the intensity of fatigue—assessed by BASDAI question 1—was comparable between the three BMI categories at the start of TNFi (overall p = 0.44; Table 1), it was significantly higher in obese patients in comparison to patients of normal weight and who were overweight at the 1-year follow-up visit: mean levels (±SD) 5.0 ± 2.4 vs. 4.0 ± 2.7 vs. 4.1 ± 2.6, respectively; overall p = 0.005. With regard to improvement of enthesitis, median MASES (interquartile range (IQR)) decreased from 1 (0–4) to 0 (0–2) in patients with normal BMI, from 2 (0–4) to 0 (0–1) in overweight patients, and from 4 (2–6) to 1 (0–3) in obese patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics at the start of first TNF inhibitor

| Parameter | n = 624 | All Patients n = 624 |

BMI category | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal n = 332 |

Overweight n = 204 |

Obese n = 88 |

|||

| BMI | 624 | 25.4 (4.3) | 22.3 (1.7) | 27.0 (1.4)* | 33.2 (3.2)* # |

| Male sex, % | 624 | 62.2 | 55.7 | 73.5* | 60.2 |

| mNYc positive, % | 437 | 73.9 | 73.1 | 75.2 | 74.1 |

| Age, years | 624 | 39.4 (11.6) | 37.4 (11.3) | 41.1 (11.7)* | 43.2 (10.5)* |

| Symptom duration, years | 619 | 13.0 (10.9) | 12.2 (10.3) | 13.6 (11.7) | 14.5 (11.0) |

| HLA-B27 positive, % | 571 | 78.1 | 80.5 | 77.2 | 70.9 |

| BASDAI | 549 | 5.5 (1.9) | 5.3 (2.0) | 5.6 (1.9) | 6.1 (1.7)* |

| BASDAI Question 1 | 556 | 6.0 (2.3) | 5.8 (2.3) | 6.1 (2.2) | 6.1 (2.0) |

| BASDAI Question 2 | 555 | 6.7 (2.3) | 6.5 (2.4) | 6.9 (2.2) | 7.0 (2.1) |

| BASDAI Question 3 | 553 | 4.2 (3.0) | 3.9 (3.0) | 4.4 (3.0) | 5.4 (2.8)* |

| BASDAI Question 4 | 556 | 5.2 (3.0) | 5.1 (3.1) | 5.2 (3.0) | 5.8 (2.9) |

| BASDAI Question 5 | 554 | 6.1 (2.7) | 5.9 (2.7) | 6.3 (2.5) | 6.6 (2.8) |

| BASDAI Question 6 | 554 | 4.9 (2.9) | 4.9 (3.0) | 4.8 (2.8) | 5.3 (2.7) |

| Patient GA | 552 | 6.4 (2.3) | 6.2 (2.5) | 6.6 (2.2) | 6.6 (2.0) |

| Physician GA | 600 | 4.9 (1.9) | 4.9 (1.8) | 4.9 (1.8) | 5.2 (2.0) |

| ASDAS | 517 | 3.5 (0.9) | 3.4 (0.9) | 3.5 (0.9) | 3.7 (0.9) |

| CRP (mg/l) | 584 | 15.1 (20.0) | 15.3 (19.0) | 14.0 (20.1) | 16.9 (23.4) |

| Elevated CRP, % | 581 | 53.4 | 54.8 | 50.0 | 55.4 |

| BASFI | 555 | 4.1 (2.5) | 3.7 (2.4) | 4.2 (2.4) | 5.0 (2.6)* |

| BASMI, median (IQR) | 540 | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–4) |

| EQ-5D | 540 | 56.2 (20.9) | 58.3 (20.7) | 54.7 (20.8) | 51.8 (21.2)* |

| Peripheral arthritis, % | 606 | 34.2 | 32.9 | 35.9 | 34.9 |

| Current enthesitis, % | 605 | 71.9 | 69.1 | 71.7 | 82.8 |

| Modified MASES, median (IQR) | 599 | 2 (0–4) | 1 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | 4 (2–6)*# |

| Dactylitis ever, % | 616 | 10.2 | 8.3 | 12.2 | 12.9 |

| Uveitis ever, % | 555 | 22.2 | 26.4 | 17.4 | 17.7 |

| Psoriasis ever, % | 478 | 12.3 | 13.0 | 10.6 | 14.3 |

| Current smokers, % | 527 | 36.4 | 39.2 | 31.2 | 38.2 |

| Education, high, % | 594 | 84.0 | 86.8 | 81.9 | 78.0 |

| Exercise score†, median (IQR) | 500 | 2.0 (0.0–4.0) | 2.0 (0.0–4.0) | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) | 1.5 (0.0–3.0) |

| On NSAIDs, % | 565 | 92.2 | 92.8 | 91.6 | 91.4 |

| On DMARDs, % | 624 | 12.5 | 11.2 | 13.2 | 15.9 |

| On steroids, % | 624 | 9.5 | 10.2 | 7.8 | 10.2 |

| First TNFi used | 624 | ||||

| Adalimumab, % | 34.5 | 35.8 | 36.3 | 25.0 | |

| Certolizumab, % | <0.1 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.0 | |

| Etanercept, % | 26.7 | 24.4 | 28.9 | 28.4 | |

| Golimumab, % | 16.9 | 17.2 | 14.2 | 21.6 | |

| Infliximab, % | 21.9 | 22.3 | 19.6 | 25.0 | |

Except where indicated otherwise, values are the mean (SD)

Significance levels of two-group comparisons are Bonferroni-corrected: *p < 0.015 compared with patients of normal weight; # p <0 .015 compared with patients who are overweight

†Exercise score refers to the number of exercise sessions per week

Normal weight = BMI 18.5–25; overweight = BMI 25–30; obese = BMI >30

ASDAS Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score, BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, BASFI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index, BASMI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index, BMI body mass index, CRP C-reactive peptide, DMARDs disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, EQ-5D EuroQol 5-domain, GA global assessment, HLA-B27 human leucocyte antigen-B27, IQR interquartile range, MASES Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score (modification refers to the inclusion of the plantar fascia in the count), mNYc modified New York criteria, NSAIDs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, TNFi tumor necrosis factor inhibitor

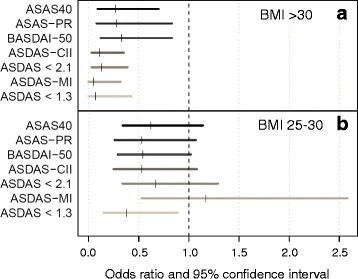

Data on disease activity at 1 year to assess at least one of the predefined validated response criteria was available in 531 patients (85%). An ASAS40 response was reached by 44%, 34%, and 29% of patients of normal weight, overweight, and obesity, respectively (overall p = 0.02; Table 2). Lower response rates for overweight and obese patients were also demonstrated for the other outcomes assessed (Table 2). Evaluation of crude ASAS40 responses following stratification for treatment with infliximab versus treatment with TNFi other than infliximab revealed similar response rates in infliximab patients (42%, 36%, and 44% of patients of normal weight, overweight and obesity, respectively; overall p = 0.83), but not in patients treated with other TNFi (Table 2). Direct comparisons between overweight patients and normal weight patients, as well as obesity and normal weight in unadjusted analyses are shown in Additional file 3 (Table S1). Adjusted logistic regression models were fitted in patients with available data regarding known predictors of response to TNFi (n = 259 for the ASAS40 response). A lower ASAS40 response was found in adjusted analyses for overweight patients vs. normal BMI patients as well as for obese patients vs. patients with normal BMI, reaching statistical significance only in the latter (odds ratio (OR) 0.62, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.24–1.14 and OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.09–0.70, respectively; Model 1 in Table 3). Significantly lower improvement criteria and status scores were also found in obese patients vs. patients with normal BMI for all the other outcomes assessed (Fig. 1a). The achievement of ASDAS improvement and status scores were particularly impaired in obesity (OR <0.15 for all four ASDAS outcomes). While lower response rates were also found for overweight patients in comparison to those with normal BMI, the differences did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 1b).

Table 2.

Crude response rates at 1 year of treatment with a first TNF inhibitor after stratification for different BMI categories

| BMI category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | n = 531 | Normal n = 282 |

Overweight n = 178 |

Obese n = 71 |

p |

| ASAS40 | 494 | 44% | 34% | 29% | 0.02 |

| ASAS40 TNFi other than INF | 383 | 45% | 34% | 24% | 0.008 |

| ASAS40 TNFi: INF | 111 | 42% | 36% | 44% | 0.83 |

| ASAS partial remission | 531 | 39% | 24% | 17% | <0.001 |

| BASDAI-50 | 488 | 48% | 40% | 33% | 0.06 |

| ASDAS improvement ≥1.1 | 423 | 59% | 46% | 37% | 0.003 |

| ASDAS <2.1 | 468 | 56% | 41% | 25% | <0.001 |

| ASDAS improvement ≥2 | 423 | 25% | 25% | 13% | 0.14 |

| ASDAS <1.3 | 468 | 29% | 15% | 10% | <0.001 |

Normal weight = BMI 18.5–25; overweight = BMI 25–30; obese = BMI >30

ASAS Assessment in SpondyloArthritis International Society, ASAS40 40% improvement according to ASAS, ASDAS Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score, BASDAI-50 50% improvement in Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, BMI body mass index, INF infliximab, TNFi tumor necrosis factor inhibitor

Table 3.

Multiple adjusted analysis of ASAS40 response in different BMI categories at 1 year of treatment with a first TNF inhibitor

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Obese (ref: normal BMI) | 0.27 | 0.09–0.70 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.05–0.59 | 0.008 |

| Overweight (ref: normal BMI) | 0.62 | 0.24–1.14 | 0.13 | 0.66 | 0.34–1.30 | 0.23 |

| Age | 1.01 | 0.99–1.04 | 0.32 | 1.01 | 0.98–1.04 | 0.36 |

| HLA-B27 | 1.31 | 0.65–2.68 | 0.46 | 1.35 | 0.67–2.79 | 0.41 |

| Male sex | 2.41 | 1.28–4.66 | 0.007 | 2.57 | 1.35–5.01 | 0.005 |

| nr-axSpA (ref: AS) | 0.38 | 0.18–0.78 | 0.009 | 0.38 | 0.18–0.78 | 0.01 |

| Current smoking yes vs. no | 0.65 | 0.36–1.18 | 0.16 | 0.64 | 0.35–1.16 | 0.15 |

| Exercise (ref: no exercise) | 0.89 | 0.50–1.58 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 0.46–1.50 | 0.54 |

| BASDAI | 1.10 | 0.95–1.27 | 0.19 | 1.10 | 0.95–1.27 | 0.20 |

| BASMI | 0.76 | 0.63–0.90 | 0.002 | 0.75 | 0.63–0.89 | 0.002 |

| Elevated CRP | 1.69 | 0.94–3.08 | 0.08 | 1.65 | 0.91–3.03 | 0.10 |

| Enthesitis | 1.34 | 0.72; 2.52 | 0.36 | 1.29 | 0.69; 2.43 | 0.43 |

| DMARDs | 1.17 | 0.51; 2.71 | 0.71 | 1.14 | 0.48; 2.67 | 0.76 |

| NSAIDs | 1.21 | 0.39; 4.24 | 0.75 | 1.13 | 0.35; 4.07 | 0.84 |

| Infliximab (ref: other TNFi) | 0.66 | 0.26–1.65 | 0.37 | |||

| Obese with infliximab (ref: other TNFi) | 3.55 | 0.41–30.1 | 0.24 | |||

| Overweight with infliximab (ref: other TNFi) | 0.73 | 0.15–3.26 | 0.68 | |||

Analysis performed in 259 patients

AS Ankylosing Spondylitis, BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, BASMI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Mobility Index, BMI body mass index, CI confidence interval, CRP C-reactive peptide, DMARDs disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, HLA-B27 human leucocyte antigen-B27, nr-axSpA nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. NSAIDs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, OR odds ratio, ref reference, TNFi tumor necrosis factor inhibitor

Fig. 1.

Impact of obesity (a) and overweight status (b) on different outcomes after 1 year of treatment with a first TNFi in multivariable analyses. Summarized results from different multivariable models with the same covariates as used in Model 1 in Table 3. ASAS40 40% improvement according to the Assessment in SpondyloArthritis International Society criteria, ASAS-PR partial remission criteria according to ASAS, ASDAS Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score, BASDAI-50 50% improvement in the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, BMI body mass index, CII clinically important improvement, MI major improvement

To analyze whether missing covariate data affected these results, unadjusted analyses were also performed for the subpopulation of patients with complete covariate values. Response rates in this subgroup of patients were comparable to the outcomes of the whole population (Additional file 4: Table S2).

In a sensitivity analysis of the adjusted ASAS40 response, we included infliximab as a covariate as well as interaction terms between infliximab administration and the different BMI groups in the model in order to account for the fact that infliximab is dosed in a weight-dependent manner (Model 2 in Table 3). Although no statistical significance could be demonstrated for these interactions, the results suggest a trend for higher ASAS40 responses in obese patients treated with infliximab versus obese patients treated with other anti-TNF agents (OR 3.55, 95% CI 0.41–30.1; p = 0.24). This trend was not found in overweight patients. However, in the overall population, a trend for lower ASAS40 responses was demonstrated in patients treated with infliximab versus patients treated with other anti-TNF agents (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.26–1.65; p = 0.37).

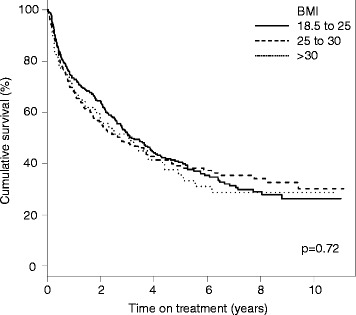

With regard to drug maintenance, Kaplan-Meyer plots demonstrated a comparable TNFi retention in the different BMI groups (log-rank test p = 0.72; Fig. 2). The result was confirmed in a multiple adjusted Cox proportional hazards model (n = 356; Table 4). The hazard ratio (HR) for discontinuing the first TNFi in obese patients in comparison to individuals with normal BMI was 1.01 (95% CI 0.63–1.65; p = 0.95). The respective HR for discontinuation in overweight vs. normal weight patients was 0.98 (95% CI 0.79-1.38; p = 0.92).

Fig. 2.

Drug survival of the first TNFi, stratified by body mass index (BMI) group

Table 4.

Multiple adjusted Cox proportional hazards model for analysis of drug discontinuation of a first TNF inhibitor in different BMI categories

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obese (ref: normal BMI) | 1.01 | 0.63–1.65 | 0.95 |

| Overweight (ref: normal BMI) | 0.98 | 0.79–1.38 | 0.92 |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.98–1.01 | 0.73 |

| HLA-B27 positivity | 0.86 | 0.60–1.25 | 0.43 |

| Male sex | 0.68 | 0.49–0.96 | 0.03 |

| nr-axSpA (ref: AS) | 1.47 | 1.01–2.14 | 0.04 |

| Current smoking yes vs. no | 0.92 | 0.66–1.28 | 0.61 |

| Exercise yes vs. no | 0.82 | 0.60–1.12 | 0.21 |

| BASDAI | 1.04 | 0.96–1.13 | 0.35 |

| BASMI | 1.07 | 0.97–1.18 | 0.17 |

| Elevated CRP | 0.71 | 0.51–0.98 | 0.04 |

| Enthesitis | 0.91 | 0.64–1.30 | 0.61 |

| DMARDs | 0.56 | 0.34–0.93 | 0.02 |

| NSAIDs | 1.00 | 0.55–1.83 | 0.99 |

Analysis performed in 343 patients

AS Ankylosing Spondylitis, BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, BASMI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Mobility Index, BMI body mass index, CI confidence interval, CRP C-reactive peptide, DMARDs disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, HLA-B27 human leucocyte antigen-B27, HR hazard ratio, nr-axSpA nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. NSAIDs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ref reference, TNF tumor necrosis factor

Discussion

Up to 50% of patients with axSpA initiating a first TNFi in the SCQM cohort presented with a BMI above the normal range, and 14% were obese. Being overweight and particularly obese was associated with an impaired response to TNFi, as assessed by a multitude of validated outcomes. While being overweight decreased the odds of achieving an ASAS40 response upon TNF inhibition by about 30%, the odds were decreased by 70% in obese patients. Achievement of ASDAS improvement and status scores was even more severely impaired in obese patients. Importantly, BMI has been shown to not affect the determination of the ASDAS in a recent analysis of the SPACE cohort [14]. A previous study had suggested that the negative impact of high BMI on treatment response might be more important in patients treated with infliximab in comparison to other anti-TNF drugs [8]. This finding is intriguing as infliximab is the only anti-TNF agent administered in a weight-dependent manner. We hereby demonstrate in a larger cohort of patients with axSpA that an impaired response to TNFi is also found for the other anti-TNF agents. The proportion of patients treated with infliximab in our study was similar in all BMI categories, indicating that rheumatologists in Switzerland do not preferentially use infliximab for axSpA treatment in overweight and obese patients. We found a trend for a better ASAS40 response in obese patients treated with infliximab in comparison to treatment with other anti-TNF agents. Our results suggest potential underdosing of subcutaneous TNFi in patients with obesity. An alternative, though not mutually exclusive, hypothesis put forward to explain the impaired treatment outcomes in obese patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases is the amplified production of proinflammatory adipokines by fat tissue [15, 16]. Obese patients with psoriatic arthritis have indeed been found to have a lower probability of achieving a sustained minimal disease activity state independently of the use of DMARDs and biologics [6].

We demonstrate that drug retention was similar irrespective of BMI category, indicating that in the absence of alternative treatment options some patients remain on a particular anti-TNF agent despite an inadequate treatment response. This is in contrast to current treatment recommendations, which stipulate to consider continuing treatment only in patients with an ASDAS and/or BASDAI improvement of ≥1.1 and ≥2, respectively [17].

A positive effect of weight loss induced by hypocaloric diet on TNFi response has been demonstrated in psoriatic arthritis [18], indicating that obesity is a manageable risk factor for the low performance of TNFi in inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Advice on the management of obesity [19, 20] might thus not only reduce cardiovascular risk but also improve therapeutic response. This might be particularly important for TNFi usage which has been shown to be associated with significant weight gain in spondyloarthritis, mostly due to an increase in android fat mass [21].

We utilized BMI as a proxy for overweight status and obesity due to feasibility issues in this large cohort. This might be suboptimal, given the individual variability in the relationship between BMI and body fat [19]. Additional data using direct quantification of fat mass in smaller cohorts of patients with axSpA might help in elucidating the pathophysiology of impaired treatment responses in patients with high BMI.

Some limitations are incurred given the observational character of our real-life cohort and, in particular, missing covariate data in the adjusted analyses. Crude response rates in the subpopulation of patients with complete data were comparable to the values in the unadjusted analyses with all available patients.

Conclusion

In conclusion, obesity is associated with significantly lower response rates to TNFi in patients with axSpA.

Additional files

Schematic representation of height correction for kyphosis using the occiput-to-wall distance. (DOC 90 kb)

Body height before and after correction for kyphosis by using the occiput-to-wall distance. (DOC 118 kb)

Impact of obesity and overweight status on different outcomes after 1 year of treatment with a first TNFi in unadjusted analyses. (DOC 34 kb)

Crude response rates at 1 year of treatment with a first TNFi after stratification for different BMI categories for the population with complete covariate data in multivariable analyses. (DOC 37 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients and their rheumatologists for participation, the members of the SCQM axSpA scientific board for contribution to x-ray scoring and helpful discussions, and the entire SCQM staff for data management and support. A list of rheumatology offices and hospitals that are contributing to the SCQM registries can be found at http://www.scqm.ch/institutions.

Funding

The SCQM Foundation is supported by the Swiss Society of Rheumatology and by AbbVie, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Janssen-Cilag, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB, and has received project-based financial supports from the Arco Foundation, Switzerland, as well as from the Swiss Balgrist Society, Switzerland.

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting our findings are shown in the article.

Abbreviations

- AS

Ankylosing spondylitis

- ASAS

Assessment in SpondyloArthritis International Society

- ASAS-PR

Partial remission criteria of the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International society

- ASDAS

Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score

- axSpA

Axial spondyloarthritis

- BASDAI

Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index

- BASDAI-50

50% improvement in BASDAI

- BASFI

Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index

- BASMI

Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Mobility Index

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- DMARD

Disease modifying antirheumatic drug

- HLA-B27

Human leucocyte antigen-B27

- HR

Hazard ratio

- MASES

Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score

- nr-axSpA

Nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis

- OR

Odds ratio

- SCQM

Swiss Clinical Quality Management

- TNFi

Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors

Author’s contributions

AC made substantial contribution to study conception and design and to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. RM made substantial contributions to study conception, data acquisition and interpretation, and helped to draft the manuscript. MH made substantial contribution to study design, was the main contributor to the statistical analyses, and helped with data interpretation and drafting of the manuscript. LW, PE, GT, JB, BM, PZ, and MJN made substantial contributions to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. AS made substantial contribution to study design, data analysis and interpretation, helped with the statistical analyses, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before recruitment to SCQM. The study was approved by the Ethics Commission of the Canton of Zurich (KEK-ZH-Nr. 2014-0439).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JB has received consulting fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, and Roche. AC has received consulting and/or speaking fees from AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. MJN has received consulting and/or speaking fees from Abbvie, Novartis, and Pfizer. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13075-017-1372-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Raphael Micheroli, Email: raphael.micheroli@usz.ch.

Monika Hebeisen, Email: monika.hebeisen@scqm.ch.

Pascale Exer, Email: exer@rheuma-basel.ch.

Giorgio Tamborrini, Email: giorgio@tamborrini.ch.

Jürg Bernhard, Email: juerg.bernhard@spital.so.ch.

Burkhard Möller, Email: burkhard.moeller@insel.ch.

Pascal Zufferey, Email: pascal.zufferey@chuv.ch.

Michael J. Nissen, Email: michael.j.nissen@hcuge.ch

Almut Scherer, Email: almut.scherer@scqm.ch.

Adrian Ciurea, Phone: ++41 44 255 29 58, Email: adrian.ciurea@usz.ch.

References

- 1.Bremmer S, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, Korman NJ, Lebwohl MG, Young M, et al. Obesity and psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(6):1058–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russolillo A, Iervolino S, Peluso R, Lupoli R, Di Minno A, Pappone N, et al. Obesity and psoriatic arthritis: from pathogenesis to clinical outcome and management. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52(1):62–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durcan L, Wilson F, Conway R, Cunnane G, O'Shea FD. Increased body mass index in ankylosing spondylitis is associated with greater burden of symptoms and poor perceptions of the benefits of exercise. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(12):2310–4. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.120595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maas F, Arends S, van der Veer E, Wink F, Efde M, Bootsma H, et al. Obesity is common in axial spondyloarthritis and is associated with poor clinical outcome. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(2):383–7. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.di Minno MN, Peluso R, Iervolino S, Lupoli R, Russolillo A, Scarpa R, et al. Obesity and the prediction of minimal disease activity: a prospective study in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65(1):141–7. doi: 10.1002/acr.21711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eder L, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, Cook RJ, Gladman DD. Obesity is associated with a lower probability of achieving sustained minimal disease activity state among patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:813–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ottaviani S, Allanore Y, Tubach F, Forien M, Gardette A, Pasquet B, et al. Body mass index influences the response to infliximab in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(3):R115. doi: 10.1186/ar3841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gremese E, Bernardi S, Bonazza S, Nowik M, Peluso G, Massara A, et al. Body weight, gender and response to TNF-alpha blockers in axial spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53(5):875–81. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciurea A, Scherer A, Exer P, Bernhard J, Dudler J, Beyeler B, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibition in radiographic and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: results from a large observational cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:3096–106. doi: 10.1002/art.38140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, Brandt J, Braun J, Burgos-Vargas R, et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(Suppl 2):ii1–44. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.104018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Listing J, Akkoc N, Brandt J, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:777–83. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciurea A, Exer P, Weber U, Tamborrini G, Steininger B, Kissling RO, et al. Does the reason for discontinuation of a first TNF inhibitor influence the effectiveness of a second TNF inhibitor in axial spondyloarthritis? Results from the Swiss Clinical Quality Management Cohort. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:71. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-0969-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Machado P, Landewe R, Lie E, Kvien TK, Braun J, Baker D, et al. Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS): defining cut-off values for disease activity states and improvement scores. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:47–53. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.138594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubio Vargas R, van den Berg R, van Lunteren M, Ez-Zaitouni Z, Bakker PA, Dagfinrud H, et al. Does body mass index (BMI) influence the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score in axial spondyloarthritis? Data from the SPACE cohort. RMD Open. 2016;2(1) doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2016-000283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Adipocytokines: mediators linking adipose tissue, inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(10):772–83. doi: 10.1038/nri1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomez R, Conde J, Scotece M, Gomez-Reino JJ, Lago F, Gualillo O. What's new in our understanding of the role of adipokines in rheumatic diseases? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(9):528–36. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewe R, Baraliakos X, Van den Bosch F, Sepriano A, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:978–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Di Minno MN, Peluso R, Iervolino S, Russolillo A, Lupoli R, Scarpa R. Weight loss and achievement of minimal disease activity in patients with psoriatic arthritis starting treatment with tumour necrosis factor alpha blockers. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):1157–62. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines OEP Executive summary: Guidelines (2013) for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Obesity Society published by the Obesity Society and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Based on a systematic review from the The Obesity Expert Panel, 2013. Obesity. 2014;22(Suppl 2):S5–39. doi: 10.1002/oby.20821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(3):254–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1514009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Briot K, Gossec L, Kolta S, Dougados M, Roux C. Prospective assessment of body weight, body composition, and bone density changes in patients with spondyloarthropathy receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha treatment. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(5):855–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Schematic representation of height correction for kyphosis using the occiput-to-wall distance. (DOC 90 kb)

Body height before and after correction for kyphosis by using the occiput-to-wall distance. (DOC 118 kb)

Impact of obesity and overweight status on different outcomes after 1 year of treatment with a first TNFi in unadjusted analyses. (DOC 34 kb)

Crude response rates at 1 year of treatment with a first TNFi after stratification for different BMI categories for the population with complete covariate data in multivariable analyses. (DOC 37 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting our findings are shown in the article.