Introduction

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), also referred to as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome is a rare, potentially life-threatening adverse drug reaction characterized by rash with fever, lymphadenopathy, hematologic abnormalities such as eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytes, and internal organ involvement. DRESS occurs within 2 to 6 weeks after the beginning of the pharmacologic treatment.1

Treatment of DRESS consists of stopping the offending medication and providing supportive care. The use of systemic steroids remains controversial because the etiology of the rash is unknown and the use of systemic corticosteroids has associated risks.2

Recently, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α as a pro-inflammatory mediator has attracted the clinician's attention. Over the last decade, TNF-α inhibitors, such as infliximab and etanercept, have been used to treat toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and Stevens Johnson syndrome (SJS), with anecdotal success.3, 4 However, to our knowledge, there is no report yet on whether a TNF-α inhibitor is effective to treat DRESS. Here we present a case of DRESS associated with lithium carbonate successfully treated with a TNF-α inhibitor (Recombinant Human TNF Receptor-IgG Fusion Protein; Qiangke, Celgen Biopharmaceutical Co, Ltd. Shanghai, China).

Case report

A 31-year-old Asian woman was admitted to the hospital because of high fever and a pruritic erythematous morbilliform eruption of 7 days' duration. She had bipolar disorder diagnosed 2 years before and had been taking mirtazapine with olanzapine tablet since then. Twenty days before the onset, her doctor changed her medication to lithium carbonate. She denied any history of hypertension, diabetes, hepatitis, tuberculosis, tumor, drug allergy, and other infectious diseases.

On physical examination, she had a fever of 38.7°C and a pruritic erythematous morbilliform rash all over her body including back, chest, legs, and arms. Other vital signs were normal. During admission, she had facial swelling, poor appetite, and swollen superficial lymph nodes.

Laboratory investigation found leukocytosis with eosinophilia and elevation of C-reactive protein, transaminases (aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase), lactate dehydrogenase, α-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase, and γ-glutamyl transferase (Table I). These laboratory results of hypertransaminasemia and leukocytosis with eosinophilia, coupled with the clinical findings of fever, swelling, systemic erythematous rash, and the recent ingestion of lithium carbonate, supported the diagnosis of DRESS. The scoring system for classifying DRESS is outlined in Table II.5 Based on this scoring system, the patient had a final score of 6, which indicates a definite case of DRESS syndrome.

Table I.

Test results at admittance

| Test | Value | Reference values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red blood cell count | 5.00 × 1012/L | N | 4.5-6 × 1012/L |

| Hemoglobin | 144 g/L | N | 135-175 g/L |

| White blood cell count | 14.4 × 109/L | ↑ | 3.5-10.5 × 109/L |

| Neutrophils | 4.0 × 109/L | N | 2.0-7.0 × 109/L |

| Lymphocytes | 55.90% | ↑ | 20%-48% |

| Monocytes | 9.80% | N | 3%-11% |

| Eosinophils | 0.7 × 109/L | ↑ | 0.02-0.52 × 109/L |

| Platelets | 141 × 109/L | ↓ | 150-450 × 109/L |

| C-reactive protein | 24 mg/L | ↑ | 0-10.0 mg/L |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 426 U/L | ↑ | 7-38 U/L |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 678 U/L | ↑ | 4-43 U/L |

| γ-glutamyl transferase | 220 U/L | ↑ | 11-50 U/L |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 1142 U/L | ↑ | 109-245 U/L |

| Urea | 2.4 mmol/L | ↓ | 2.8-7.1 mmol/L |

| Creatinine | 70 μmol/L | N | 45-84 μmol/L |

| α-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase | 780 U/L | ↑ | 72-182 U/L |

| Fasting blood glucose | 6.44 mmol/L | ↑ | 3.89-6.11 mmol/L |

Table II.

Scoring system for classifying DRESS cases

| Score | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever ≥ 38.5°C | No/U | Yes | ||

| Enlarged lymph nodes | No/U | Yes | ||

| Eosinophilia | No/U | |||

| Eosinophils | 0.7-1.499 × 109/L | ≥1.5 × 109/L | ||

| Eosinophils, if leukocytes <4.0 × 109/L | 10%-19.9% | ≥20% | ||

| Atypical lymphocytes | No/U | Yes | ||

| Skin involvement | ||||

| Skin rash extent (% body surface area) | No/U | >50% | ||

| Skin rash suggesting DRESS | No | U | Yes | |

| Biopsy suggesting DRESS | No | Yes/U | ||

| Organ involvement∗ | ||||

| Liver | No/U | Yes | ||

| Kidney | No/U | Yes | ||

| Muscle/heart | No/U | Yes | ||

| Pancreas | No/U | Yes | ||

| Other organ | No/U | Yes | ||

| Resolution ≥15 d | No/U | Yes | ||

| Evaluation of other potential causes | ||||

| Antinuclear antibody | ||||

| Blood culture | ||||

| Serology for HAV/HBV/HCV | ||||

| Chlamydia/mycoplasma | ||||

| If none positive and ≥3 of above negative | Yes | |||

| Final score | 6 | |||

From Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611; reprinted with permission.

Bold indicates that the patient had this score/criteria during admission.

HAV, Hepatitis A virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; U, unknown/unclassifiable.

After exclusion of other explanations: 1, one organ; 2, two or more organs. Final score <2, no case; final score 2-3, possible case; final score 4-5, probable case; final score >5, definite case.

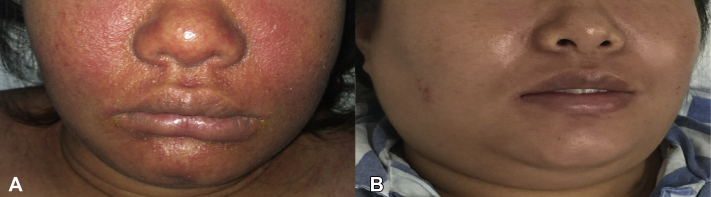

TNF-α inhibitor: Recombinant human TNF receptor-IgG fusion protein was then administered via subcutaneous injection once every 3 days with the first dose doubled (50 mg) and then 25 mg thereafter. After the initial injection, the patient's condition was observed and monitored frequently. Serum aminotransferase levels started to decrease significantly after the first injection and returned to the normal range within 2 weeks. White blood cell count and C-reactive protein continued increasing after the first injection, then began to decrease after second injections, and gradually returned within the normal range in 2 weeks. Eosinophil count continuously increased after the first injection, reached its peak on day 7, and decreased gradually thereafter. No new rash appeared after the first injection, but the pruritus worsened, desquamation began 3 days later, then after a week, the cutaneous condition continued to improve. Within 12 days, the rash subsided significantly. The patient recovered after the total of 5 injection of TNF-α inhibitor (recombinant human TNF receptor-IgG fusion protein) accompanied by supportive and symptomatic treatment (Fig 1, A and B).

Fig 1.

A, Prominent facial edematous erythema of patient at initial presentation. B, Resolution of the rash and swelling over the face after TNF-α inhibitor treatment.

Discussion

TNF-α is involved in cell differentiation, mitogenesis, cytotoxic responses, inflammation, immunomodulation, and wound healing. The inhibition of TNF-α may help in the treatment of certain dermatologic diseases such as psoriasis, hidradenitis suppurativa, pyoderma gangrenosum, Behcet syndrome, and graft-versus-host disease. The efficacy of these agents has proven impressive, and short-term side effects are few and relatively benign.6

Two cases have been reported that showed rapid resolution of skin lesions in TEN after systemic anti–TNF-α therapy with infliximab (5 mg/kg as single-shot therapy).7 Etanercept is another TNF-α inhibitor that had promising results in a series of 10 patients with SJS/TEN who were given a single 50-mg subcutaneous dose with rapid re-epithelialization and no deaths despite a score of toxic epidermal necrolysis–predicted mortality rate of 50%.8 Hunger et al4 also reported 1 TEN patient treated with a single dose of the chimeric anti–TNF-α antibody (infliximab, 5 mg/kg) and reported that disease progression stopped within 24 hours followed by a complete re-epithelialization within 5 days.4 These cases support the theory that TNF-α is significantly involved in the tissue damage, and TNF-α inhibitors can induce rapid resolution of skin lesions in the SJS/TEN patient. In our case, we observed that after the first injection of a TNF-α inhibitor, no new rash appeared, desquamation began 3 days later, then after a week, the cutaneous condition continued to improve rapidly followed by progressive re-epithelialization. The rash subsided dramatically within 12 days. The pruritus continued to persist during the treatment because TNF-α inhibitor seems to have no inhibitory effects on the eosinophil infiltration; thus, pruritus did not completely disappear until the end of treatment. The patient reported that the level of pruritus was significantly reduced at the end of treatment.

Some investigators speculated that there is a 10% mortality rate from DRESS, mostly from liver damage, which is thought to be secondary to eosinophilic infiltration.9 According to this finding, increased eosinophil count should be accompanied or followed by elevated serum aminotransferase levels. However, in our case, serum aminotransferase levels started to decrease after the first injection and returned to the normal range within 2 weeks. On the contrary, peripheral eosinophil count was continuously increasing after the first injection, reached its peak on day 7, and was restored to the normal range within 2 weeks. Therefore, we speculate there are 2 factors that lead to liver damage as shown by the elevated transaminases: the first is drug-induced cytotoxicity leading to liver cell apoptosis and the second is eosinophilic infiltration of the liver. Based on the results of our case, it seems that the TNF-α inhibitor had no inhibitory effect on eosinophils; however, the TNF-α inhibitor did reduce the level of transaminases dramatically thus reducing the mortality risk from liver damage. This case was followed up after 6 month with no relapsed reported.

To our knowledge, this is the first case in the English-language literature that reports the use of TNF-α inhibitor as the primary treatment of DRESS. The patient showed positive improvement to the drugs and recovered. We believe that in the future, TNF-α inhibitors could be considered as an alternative treatment for DRESS patients. Further clinical studies are required to clarify.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.El Omairi N., Abourazzak S., Chaouki S., Atmani S., Hida M. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptom (DRESS) induced by carbamazepine: a case report and literature review. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;18:9. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.9.3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim K.M., Sung K., Yang H.K. Acute tubular necrosis as a part of vancomycin induced drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome with coincident postinfectious glomerulonephritis. Korean J Pediatr. 2016;59:145–148. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2016.59.3.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gubinelli E., Canzona F., Tonanzi T., Raskovic D., Didona B. Toxic epidermal necrolysis successfully treated with etanercept. J Dermatol. 2009;36:150–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunger R.E., Hunziker T., Buettiker U., Braathen L.R., Yawalkar N. Rapid resolution of toxic epidermal necrolysis with anti-TNF-alpha treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:923–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kardaun S.H., Sidoroff A., Valeyrie-Allanore L. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trent J.T., Kerdel F.A. Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors for the treatment of dermatologic diseases. Dermatol Nurs. 2005;17:97–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer M., Fiedler E., Marsch W.C., Wohlrab J. Antitumour necrosis factor-alpha antibodies (infliximab) in the treatment of a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:707–709. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.46833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paradisi A., Abeni D., Bergamo F., Ricci F., Didona D., Didona B. Etanercept therapy for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tas S., Simonart T. Management of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome): an update. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland) 2003;206:353–356. doi: 10.1159/000069956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]