Abstract

Neurons begin life as spherical cells. A major hallmark of neuronal development is the formation of elongating processes from the cell body which subsequently differentiate into dendrites and the axon. The formation and later development of neuronal processes is achieved through the concerted organization of actin filaments and microtubules. Here, we review the literature regarding recent advances in the understanding of cytoskeletal interactions in neurons focusing on the initiation of processes from neuronal cell bodies and the collateral branching of axons. The complex crosstalk between cytoskeletal elements is mediated by a cohort of proteins that either bind both cytoskeletal systems or allow one to regulate the other. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of microtubule plus-tip proteins in the regulation of the dynamics and organization of actin filaments, while also providing a mechanism for the subcellular capture and guidance of microtubule tips by actin filaments. Although the understanding of cytoskeletal crosstalk and interactions in neuronal morphogenesis has advanced significantly in recent years, the appreciation of the neuron as an integrated cytoskeletal system remains a frontier.

Keywords: axon sprouting, microtubule dynamics, growth cone, F-actin, filopodia, microtubule associated proteins, plus tips, lamellipodia

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview of the neuronal cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a dynamic and regulated system that shapes the morphology of cells. The importance of cellular morphogenesis is especially evident during development when neurons establish patterns of connectivity and elaborate morphologically complex dendrites and axons. Dendrites tend to be tapered processes that do not extend great distances from the cell body, but can undergo significant amounts of branching. In contrast, neurons generate a single axon of relatively uniform caliber that can be up to meters in length in large animals. Axon branching occurs in the target fields of the main axon and also along the length of the axon through collateral branching (Gibson and Ma, 2011; Kalil and Dent, 2014). Collateral branching involves the generation of a new axon branch from the main axon independent of the growth cone at the tip of the extending axon. This form of branching allows the single axon to establish complex patterns of connectivity in multiple regions of the nervous system and also cover an expanded territory in its synaptic target fields. This review will focus on the initiation of processes from neuronal cell bodies and the collateral branching of axons.

The neural cytoskeleton is composed of three classes of structural elements: actin filaments (often referred to as F-actin for filamentous actin), microtubules and neurofilaments. Neurofilaments will not be considered in this review as there is little to no evidence of their involvement in the initiation or branching of axons. In contrast, the actin filament and microtubule cytoskeleton underlie all stages of neuronal morphogenesis (Dent and Gertler, 2003; Kevenaar and Hoogenraad, 2015). Actin filaments and microtubules are dynamic polymers respectively assembled from ATP-bound actin monomers and GTP-bound α-β-tubulin heterodimers. Actin filaments and microtubules are polarized polymers. In both cases, one end of the polymer exhibits much greater rates of polymerization than the other. These ends are termed the “barbed end” and “plus end” for actin filaments and microtubules, respectively. The opposite ends of the polymers are referred to as the “pointed” and “minus” end for actin filaments and microtubules. The barbed ends of actin filaments are involved in the generation of protrusive structures (e.g., finger-like filopodia and veil-like lamellipodia). At the plasma membrane, a major site for filament polymerization, the barbed ends face the inner leaflet of the membrane. The disassembly of filaments occurs at the pointed end, which is usually directed away from the membrane. Filopodia are characterized by a uniform bundle of actin filaments with the barbed ends directed distally toward the tip of the filopodium where their polymerization drives the tip of the filopodium forward. In contrast, lamellipodia exhibit meshworks of actin filaments of varying orientations, but as with filopodia the polymerization of actin filaments near the membrane drives the lamellipodium forward. In both cases the actin filaments also undergo retrograde flow. Retrograde flow refers to the centripetal displacement of the filaments away from the filopodial tip or lamellipodial edge. In axons, microtubules have an almost uniform polarity with the plus ends directed toward the terminus of the axon and the minus ends toward the cell body. Within the axon microtubule plus ends undergo bouts of polymerization and depolymerization, collectively referred to as dynamic instability.

The formation of new actin filaments and microtubules requires an initial nucleation event forming the seed of the polymer that will be subsequently elongated through polymerization. Actin filaments are nucleated through a variety of molecular systems that can generate individual filaments or give rise to a new filament from the side of an existing filament (Skau and Waterman, 2015). The nucleation of actin filaments can occur anywhere in the cell where the relevant nucleation systems are targeted and activated. Nucleation mechanisms are usually localized at the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane or other intracellular membranes. In contrast, the majority of axonal microtubules are considered to be nucleated at the somatic centrosome. However, recent evidence indicates that neuronal microtubules may also be nucleated independent of the centrosome (Kuijpers and Hoogenraad, 2011). Within the axon microtubules are considered to undergo active transport. The transport delivers microtubules to the distal axon, thereby contributing to axon extension. The polymerization of microtubules in axons, particularly at the terminus of the axon, is also of fundamental importance to axon extension (Dent and Gertler, 2003).

The axon is supported by a parallel array of microtubules. Depolymerization of microtubules results in the fragmentation of the axon. Other than to serve as the major structural support for the axon, an additional role of axonal microtubules is to provide the substrate for the axonal transport of a variety of cargoes ranging from organelles, protein complexes and mRNAs (in protein particles) (Maeder et al., 2014). The dynamic instability of axonal microtubules is greatest at the terminus of the growing axon. The microtubules along the axon shaft have decreased dynamics and increased structural stability. In contrast, in a developing neuron, the concentration of actin filaments is greatest at the terminus of the axon comprising the growth cone. The growth cone is a highly motile structure characterized by actin filament dependent filopodia and/or lamellipodia. The concentration of actin filaments drops precipitously along the axon behind the growth cone (usually comprising the distal 10–15 microns of the axon). Within the axon proper, actin filaments have been described to occur in a variety of super-structures including small localized meshworks termed actin filament patches, circumferential small bundles of actin, and also filament populations arranged longitudinally (Arnold and Gallo, 2014; Ganguly et al., 2015)

In summary, both microtubules and actin filaments have fundamental roles in the development of axons. The two cytoskeletal systems have mostly distinct roles in axonal biology, but cooperate in order to generate a fully functional axon. This review will focus on how actin filaments and microtubules can coordinate one another through indirect physical interactions and the regulation of cellular mechanisms that are controlled by one cytoskeletal element but converge on the other.

1.2 The cytoskeletal basis of axon initiation and branching

Because the details of the cytoskeletal involvement in neuronal morphogenesis are usually investigated using in vitro model system, which provide a high degree of spatio-temporal detail, this section begins with an overview of the relevant aspects of neuronal morphogenesis from in vitro models. The majority of neuronal cell types exhibit a single axon and multiple dendrites. In vitro both axons and dendrites differentiate from an initial set of undifferentiated short processes generated by the cell body termed “minor processes” (Neukirchen and Bradke, 2011a; Sainath and Gallo, 2015). One of these processes then becomes the axon and the rest develop into dendrites. The formation of minor processes is mediated by the extension of actin filament dependent filopodia or lamellipodia from the cell body. Microtubules subsequently enter the filopodium and allow the filopodium to mature into a minor process. An increase in the levels of actin filaments and the generation of frequent dynamic protrusions by the growth cone of one of the minor processes is an early hallmark of the differentiation into an axon. The differentiated axon then begins to elongate at a much greater rate than the remaining processes. The formation of an axon collateral branch from the main axon shaft follows a relatively similar sequence as that of the formation of minor processes from the cell body. As noted previously, the axon exhibits relatively low levels of actin filaments. However, axons locally generate small meshworks of actin filaments termed “axonal actin patches” (Arnold and Gallo, 2014; Kalil and Dent, 2014). Actin patches in turn serve as the platforms for building a filopodium or can expand into protrusive lamellipodia, the structures that serve as the first step in the establishment of a branch. As with the initiation of minor processes, the next required event is the invasion of axonal microtubules into the axonal protrusion. Depending on the cell system and microenvironment, microtubules can target into axonal protrusions through either plus tip mediated polymerization or by axonal transport (Dent et al., 2004; Gallo and Letourneau, 1999). The mere entry of microtubules into protrusive structures is not sufficient without stabilization of the microtubules in situ, which would otherwise be removed by depolymerization or possibly retrograde transport.

A shared and fundamental aspect of both minor process development and axon branching is that the initial actin filament based protrusion must undergo polarization resulting in the formation of a growth cone like structure at its tip (Gallo, 2011; Gallo, 2013; Lewis et al., 2013). The filopodial actin filament bundle must be reorganized, and the mechanism of actin filament nucleation and polymerization become polarized to the tip of the nascent process. Similarly, if the process is generated by a lamellipodial precursor, the actin filament based protrusive activity must become polarized distal to the plus tips of the emerging microtubule core. Microtubules have fundamental roles in the establishment of this polarity. Suppression of microtubule dynamics, thereby preventing microtubules from entering the actin filament based protrusions, abrogates the process. The contributions of microtubules and actin filaments to the maturation of a filopodium into a process or axon branch are further discussed toward the end of this review (Section 6). In conclusion, both actin filaments and microtubules play necessary roles in axon initiation and branching, but neither is sufficient.

2. Evidence for actin filament and microtubule interactions and crosstalk in neurons

2.1 Growth Cones

Even though microtubules and actin filaments have different roles in the biology of a neuron, the two cytoskeletal systems cooperate during neuronal morphogenesis. The concept of cytoskeletal crosstalk/crossregulation was initially derived from studies in non-neuronal cells and purified biochemical systems. Multiple classes of mechanisms used by the two cytoskeletal systems to cooperate and regulate one another have emerged. Griffith and Pollard (1978) reported that mixtures of actin filaments and microtubules exhibited increased viscosity when in the presence of microtubule associated proteins (MAPs) (Griffith and Pollard, 1978). While at the time the molecular nature of the MAPs was unclear, these data and electron microscopic analysis provided evidence that MAPs could crosslink the two cytoskeletal systems. This type of evidence led to the idea that indirect physical links between the two systems are likely to have important roles in the organization, and perhaps dynamics, of the cytoskeleton as a whole. An additional mechanism for crosstalk also emerged based on the idea that one cytoskeletal system can direct the physiology of the other through signaling and regulatory mechanisms beyond the physical association of the two systems. Early evidence for these types of interactions came from studies addressing the effects of depolymerizing or attenuating the dynamics of one system on the other. In pioneering studies (Vasiliev et al., 1970), Vasiliev and colleagues reported that depolymerizing microtubules using a variety of reagents resulted in a loss of cell polarity in non-neuronal cells. In migrating cells the leading edge is high dynamic, due to actin filament dynamics, while the sides and rear of the cell are relatively quiescent. Following depolymerization of microtubules this polarity was lost, and cells begun to exhibit protrusive activity around a large portion of their perimeter. Bershadsky and colleagues later found that depolymerizing microtubules in fibroblasts also attenuated the protrusive behavior of the cell’s leading edge as reflected in decreased bouts of lamellipodial retraction and protrusion (Bershadsky et al., 1991). These observations on the role of microtubules in regulating protrusive activity were later also found to apply to neuronal growth cones using experimental protocols that selectively inhibit microtubule dynamic instability (Gallo, 1998; Tanaka et al., 1995). Conversely, decreasing the turnover of actin filaments in axons results in the compression and buckling of the axonal microtubule array through actomyosin driven contractility (Gallo, 2002). These studies indicate that (1) microtubules and their dynamic instability can regulate the dynamics of actin filaments that drive cellular protrusions, and (2) actin filament dynamics can impact the axonal microtubule array. Although the focus of this review is not on growth cones, this section uses the growth cone to present the various forms of cytoskeletal interactions that have been described, which have been most thoroughly characterized in growth cones.

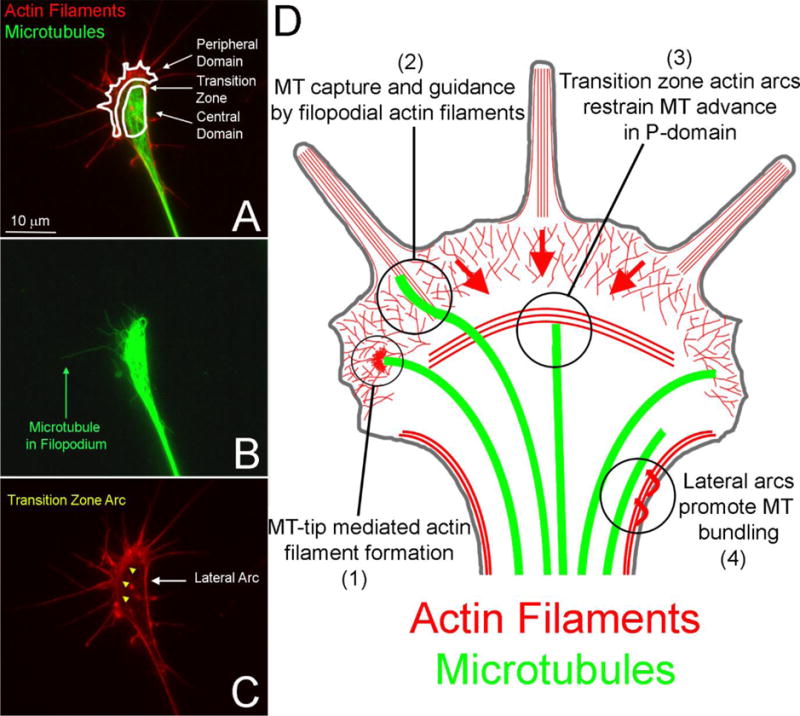

Growth cones consist of two major domains termed the peripheral and central domains, separated by a transition zone (Figure 1). The organization of actin filaments in growth cones is complex and consists of multiple types that are regulated at the sub-growth cone level on a scale of a few microns. While not all of these multiple forms of actin filament organization are observed in all growth cones all the time, individual growth cones and their actin filament cytoskeleton undergo constant remodeling and thus over time tend to exhibit these types of organization. The previous text introduced filopodia and lamellipodia, which predominate in the peripheral domain of growth cones. However, actin filaments are also found in the central domain/transition zone of growth cones and on the relatively quiescent lateral portions of growth cones (Figure 1), the latter termed the growth cone neck. In the central domain dynamic foci of actin filaments represent the formation of invadosome-like structures that serve to remodel the extracellular matrix through local secretion of enzymes (Santiago-Medina et al., 2015). In the transition zone growth cones can exhibit “actin arcs”. Transition zone actin arcs are linear bundles of actin filaments organized roughly perpendicular to the axis on the axon (Figure 1). Similar bundles of actin filaments have also been observed in the lateral portions of the polarized growth cone, referred to as lateral actin arcs (Figure 1). Actin arcs have important roles in the regulation of microtubule organization. As previously noted, within the main axon microtubules form a uniform bundle. However, the microtubules in growth cones splay apart, and their tips can also penetrate the peripheral domain. Depolymerization of growth cone actin filaments results in the pronounced advance of microtubules and associated organelles normally constrained in the central domain into the peripheral domain (Forscher and Smith, 1988). This effect is dependent on actin filaments and myosin II contractility of the filaments (Schaefer et al., 2008). Inhibition of myosin II also increases the distance that microtubules penetrate into growth cone filopodia (Ketschek et al., 2007). The transition zone actin arcs serve to move microtubules out from the peripheral domain and into the central domain of the growth cone, thereby impairing the microtubule-dependent advance of the growth cone (Schaefer et al., 2002). When growth cones are on substrata that promote relatively fast axon extension transition zone arcs are minimal and transient, and the arcs are most readily observed on substrata on which axon extension is slower. The lateral actin arcs serve a similar role as the transition zone arcs in determining microtubule distribution within growth cones. The myosin II dependent constriction of lateral arcs promotes the bundling of microtubules in the central domain (Burnette et al., 2008), thereby assisting in the formation of the axonal microtubule bundle as the growth cone advances. Lateral actin arcs undergoing myosin II driven contraction toward the center of the growth cone interact with microtubules and bring them into close apposition with microtubules located more centrally in the growth cone (Figure 1D). Microtubule-microtubule interactions are then considered to mediate the bundling of the microtubules displaced by lateral actin arcs with those present in the center of the growth cone. The actin filament bundle of filopodia, which in some cases can extend into the filament meshwork present in the peripheral domain lamellipodia, can also serve as a guide for microtubules to exhibit linear directed polymerization (Schaefer et al., 2002). However, these filopodial bundles are not necessary for the entry of microtubule plus tips into the peripheral domain (Burnette et al., 2007). In general, the regulation of microtubules in growth cones by actin filament based structures is due to myosin II-driven forces acting on actin filaments. As previously discussed, actin filaments undergo myosin II dependent retrograde flow (Lin et al., 1996). Although the specific molecules linking microtubules to actin filaments in these various contexts remain to be determined, it is assumed that microtubules can become linked to actin filaments and thus be subjected to the same myosin II forces as the filaments.

Figure 1.

Overview of the organization of actin filaments and microtubules (MT) in growth cones. (A) Example of the distribution of actin filaments and microtubules in the growth cone of an embryonic chicken sensory neuron axon. The entire growth cone with its domains are outlined and denoted. The peripheral domain consists of lamellipodia and filopodia supported by actin filament meshworks and bundles respectively. (B) The distribution of microtubules in the growth cone. Note that although a few microtubules penetrate the peripheral domain, the majority are restricted to the central domain proximal to the transition zone. An example of a microtubule which has penetrated a filopodium is denoted. (C) Localization of the transition zone arcs (yellow arrowheads) and lateral arcs discussed in the text. (D) Schematic summary of actin filament-microtubule interactions in growth cones discussed in Section 2.1. The red arrows in the peripheral (P) domain denote the direction of actin filament retrograde flow. Clockwise: (1) Microtubule plus tips can locally drive actin filament polymerization. (2) The actin filament bundles of filopodia can capture and guide microtubules. (3) Transition zone actin arcs restrain forward microtubule advance in the P-domain and the retrograde flow of actin filaments coupled to microtubules displaces them centripetally. (4) The contractility of the lateral actin arcs toward the central domain and axis of the axon (denoted by arrows) promotes the bundling of splayed microtubules in the growth cone as the growth cone advances.

Evidence has also been presented for microtubule plus tip mediated regulation of actin filament dynamics in growth cones. Two studies found that microtubule dynamic instability is required for the formation of actin filament foci in growth cones (Grabham et al., 2003; Rochlin et al., 1999). Treatment of growth cones with laminin induced the formation of actin foci that was blocked by inhibition of dynamic instability and the activity of the Rac1 GTPase (Grabham et al., 2003). Furthermore, the tips of microtubules were detected to target to sites of foci formation and Rac1 colocalized with the tips of microtubules even when actin filaments were depolymerized. A similar role for microtubule dynamics in regulating signaling and actin filament accumulation within growth cones also emerged from a study addressing the mechanism of growth cone turning toward beads coated with apCAM (Suter et al., 2004), an IgG superfamily cell adhesion molecule. apCAM coated beads placed on one side of the growth cone cause the growth cone to turn toward the bead. The turning involves the attenuation of actin filament retrograde flow allowing microtubules to polymerize toward the site of contact with the bead. It was found that inhibiting microtubule dynamics prevents the accumulation of actin filaments and activated Src, a kinase required for the turning, at the site of bead contact. This observation indicates that microtubule dependent mechanisms regulate actin and Src activation. Collectively, these studies provide evidence that microtubule dynamics can control the actin cytoskeleton and the localization and/or activation of relevant signaling pathways in neuronal growth cones.

2.2. Axon branching and initiation

Evidence for cytoskeletal crosstalk has also been presented in the context of the invasion of filopodia by microtubules during the initial steps of process formation from the cell body and the emergence of axon collateral branches. In sympathetic neurons, the entry of microtubules into filopodia formed by the cell body was found to correlate with accumulating actin filaments and microtubule targeting to the filopodia independent of their dynamic instability (Smith, 1994a; Smith, 1994b). In contrast, in cortical neurons microtubule dynamic instability is required to target microtubules into filopodia (Dent et al., 2007), although the relationship between filopodia and microtubules during the initiation of processes from the cell body is as reported for sympathetic neurons. The targeting of microtubules into somatic filopodia of cortical neurons requires filopodia actin filament bundles as guides (Dent et al., 2007). The local regulation of actin filament dynamics by actin depolymerizing factor/cofilin (AC) has also been shown to regulate the formation of processes from neuronal cell bodies (Flynn et al., 2012). Analysis of filament organization in AC knockout neurons during early stages of process formation revealed increased levels of actin filaments arranged parallel to the cell’s edge, perhaps similar to actin arcs in growth cones but apparently not tightly bundled. In the context of axon branching, the localization of microtubules into axonal filopodia can occur through either plus tip polymerization or the transport of preassembled polymer into filopodia depending on neuron type or extracellular environment (Dent et al., 2004; Gallo and Letourneau, 1999), as also observed for initial process formation. Experimental manipulation of either actin filament or microtubule dynamics during axon branching also affects the dynamics of the non-manipulated cytoskeletal system (Dent and Kalil, 2001), indicating bidirectional regulation of the actin filament and microtubule cytoskeleton. Whether similar bidirectional cytoskeletal crosstalk occurs during process formation from the cell body has not been clarified.

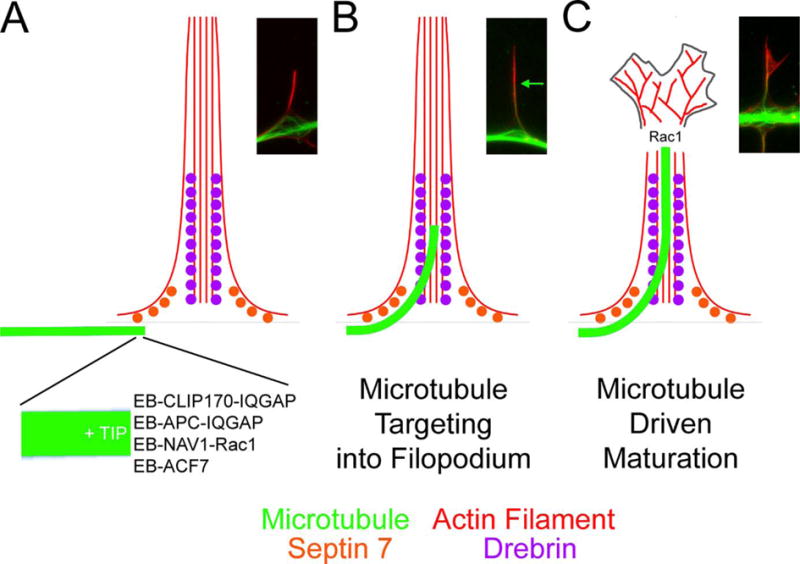

The formation of axon branches correlates with a localized splaying of the normally bundled and uniform microtubule array (see Figure 2). The mechanism that promotes the localized splaying of axonal microtubules remains to be determined. However, a recent paper provided evidence that actomyosin contractility along the axon negatively regulates the ability of microtubules to undergo splaying (Ketschek et al., 2015). This study reports that nerve growth factor (NGF), a strong inducer of axon branching in sensory neurons, promotes the formation of sites of microtubule debundling prior to the commencement of branching. Depolymerization of actin filaments or inhibition of myosin II potentiated the effects of NGF on microtubule splaying. The negative regulation of the splaying of the axonal microtubule array by actomyosin contractility may be similar to that observed at the growth cone neck generated by lateral actin arcs detailed above. However, no actin arcs are detected along the axon shaft, prior to commencement of branching. Furthermore, this study also provided platinum replica electron microscopic evidence for close physical contact between actin filaments and axonal microtubules at sites of microtubule splaying.

Figure 2.

Proposed working model for the targeting of microtubule plus tips into filopodia and the maturation of filopodia into neuronal processes or collateral branches. Alongside the schematic in each panel an example of the organization of actin filaments (red) and microtubules (green) during the process of collateral branch formation by embryonic sensory neurons is also shown. Note the splaying of axonal microtubules at sites of filopodia formation and branching. (A) The plus tips of microtubules are decorated with EB proteins which in turn recruit +TIP proteins. Binding partners of +TIP proteins act as effectors of microtubule plus tips, particularly through the regulation of the Rac1 GTPase and its downstream effectors. (B) The microtubule plus tip is initially guided into the most proximal portion of filopodia through associations with septin 7 and drebrin. Drebrin, due to its more distal distribution along filopodia, then promotes the continued elongation of microtubule plus tips along the filopodial actin filament bundle. Note: The organization of the actin filaments is simplified for didactic purposes. For detailed structural information regarding the organization of actin filaments in axonal filopodia see Spillane et al (2011). The green arrow in the image shows the distal most extent of the microtubule tip along the filopodium. (C) The competence of the microtubule plus tip to support Rac1 signaling is in turn predicted to promote the reorganization of the actin filament bundle into a polarized structure allowing the filopodium to give rise to a process of a branch. This last proposed step has not been experimentally detailed. However, Rac1 is involved in the formation of lamellipodial structures which are a hallmark of the formation of the polarized growth cone which characterizes mature processes and branches.

The studies discussed above have identified multiple levels of the coordinated regulation of the actin filament and microtubule cytoskeletal systems during branching and process initiation from the cell body. This section provided and overview of the described functional and structural relationships between actin filaments and microtubules. The next sections review relevant studies focusing on specific molecules that may mediate crosstalk/crosslink between actin filaments and microtubules.

3. Microtubule Associated Proteins

Some microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) have been identified as microtubule and actin cytoskeletal cross linkers. MAPs bind along microtubules and are usually found throughout axons including at the growth cone. Overall, MAPs are considered to have structural roles and organize microtubules while also regulating a variety of microtubule related processes such as axonal transport. This section focuses on MAPs with demonstrated roles in axon initiation or branching.

3.1. MAP2

The structural MAP1, 2 and 4 proteins have the potential to bridge actin and microtubules (Mohan and John, 2015). However, only the MAP2 family has been found to be involved in axon initiation, and little is known about the role of any member of this family in axon branching. MAP2 is expressed by neurons and has the potential to bind both actin filaments and microtubules, and it localizes to minor processes and dendrites but it is excluded from mature axons (Dehmelt and Halpain, 2005). MAP2 proteins are abundant neuronal MAPs and they are associated with actin filaments, including in filopodia, during the period of minor process formation but later also associate with microtubules (Kwei et al., 1998). There are different isoforms but only MAP2c is expressed in the axons (Mohan and John, 2015). MAP2c utilizes one domain to mediate the interaction between actin filaments and microtubules. It is not clear whether MAP2 can interact with the two polymers simultaneously, and both in vitro and in vivo studies show that the binding affinity of MAP2 to actin is much lower than for microtubules (Ozer and Halpain, 2000; Sattilaro, 1986). MAP2c is involved in axon initiation and elongation in cultured neurons (Caceres et al., 1992) and in Neura-2a neuroblastoma cells (Wang et al., 1996). One model for axon formation envisions MAP2c as a stabilizer of microtubule bundles that translocate to the membrane where they exert a dynein dependent force to trigger protrusion formation (Dehmelt et al., 2006). Overexpression of MAP2c in Sf9 cells leads to the formation of protrusions that resemble neuronal processes (LeClerc et al., 1993). Dehmelt et al. (2003) demonstrated that MAP2c coordinates rearrangements of microtubules with forward protrusion of lamellipodia to establish a newly formed growth cone in primary neurons. MAP2c could thus directly or indirectly alter actin organization during process initiation (Dehmelt et al., 2003). The microtubule binding domain of MAP2c is necessary and sufficient for actin filament binding and bundling activities, and the actin binding activity promotes neurite initiation in neuroblastoma Neuro-2a cells (Roger et al., 2004). Suppression of MAP2 expression in cerebellar macroneurons blocked the formation of minor processes (Caceres et al., 1992). When MAP2 levels were decreased through antisense oligonucleotides the neurons never formed processes and instead retained a flattened lamellipodial morphology, indicating MAP2 is involved in the reorganization of the actin filament based lamellipodium into a minor process.

3.2. MAP1B

MAP1B is predominantly expressed in the axons of developing neurons in the embryo but also expressed in the adult. MAP1B can bind both actin filaments and microtubules in a phosphorylation dependent manner (Cueille et al., 2007; Pedrotti and Islam, 1996; Togel et al., 1998). Multiple reports have provided evidence that MAP1B is a negative regulator of axon branching in both adult and embryonic neurons (Barnat et al., 2016; Bouquet et al., 2004; Dajas-Bailador et al., 2012; Tymanskyj et al., 2012). MAP1B has also been involved in the actomyosin dependent retraction of axons that drives the buckling of the axonal microtubule array in a MAP1B dependent manner indicating some form of crosstalk or coordination between the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton (Bouquet et al., 2007). The specifics of the role of MAP1B in acting as a negative regulator of axon branching remain to be determined. However, it seems likely it is involved in the early step in branching. Two recent studies in adult rat and embryonic chicken sensory neurons presented differing observations on the levels of phosphorylated MAP1B at branch points. In adult rat neurons the levels of phosphorylated MAP1B were decreased at branch points (Barnat et al., 2016). In contrast, in the embryonic chicken neurons no relationship between MAP1B phosphorylation and branch points was noted (Ketschek et al., 2015). However, in both of these studies evidence was presented for a role of glycogen synthase kinase beta (GSKβ) in regulating MAP1B phosphorylation in branching. The study using embryonic neurons presents an analysis of the localization of MAP1B and MAP1B phosphorylated at the GSKβ site along microtubules in branches at different stages of formation. For both MAP1B and phospho-MAP1B, levels along microtubules in emerging collaterals were high for branches that formed in the absence of treatment with the branch inducing factor NGF but low along branches induced by acute treatment with NGF. MAP1B and its phosphorylated form were detected in longer established branches regardless of NGF treatment. Overall, the literature provides consistent evidence that MAP1B is a negative regulator of axon branching, but additional investigation is required to determine the specific mechanism and possible role of MAP1B in orchestrating interactions between microtubules actin filaments.

An early study provided evidence that antisense knockdown of MAP1B inhibited the formation of processes from the neuron-like PC12 cell line (Brugg et al., 1993) However, shRNA mediated knockdown in cultured primary cortical or sensory neurons and genetic knockout in adult sensory neurons do not change the number of axons/processes formed from cell bodies (Bouquet et al., 2004; Tymanskyj et al., 2012). Similarly, no effect of genetic MAP1B knockout was observed for the in vitro development of minor processes and axon differentiation by hippocampal neurons (Takei et al., 1997). Thus, MAP1B may be involved in process formation in neuron-like cells lines but not in primary neurons.

4. Microtubule plus end associated proteins

Microtubule dynamics are regulated by plus end tracking proteins (+TIPs) that accumulate at the ends of actively polymerizing microtubules (Mimori-Kiyosue et al., 2000; Perez et al., 1999) and control different aspects of neuronal development and function (Hoogenraad and Bradke, 2009). +TIPs form dynamic interactions with other protein complexes through which they can indirectly regulate actin filaments. Many +TIPs can couple microtubules to F-actin dynamics in the growth cone to drive axon guidance (Bearce et al., 2015; Cammarata et al., 2016). In this section, we will focus on those +TIPs involved in actin-microtubule crosstalk during axon initiation and branching.

4.1. End binding (EB) proteins

EBs are the most abundant plus-end binding proteins. They can autonomously track growing microtubule plus ends recognizing a structural cap (van de Willige et al., 2016) and are useful markers for polymerizing microtubule tips in axons (Stepanova et al., 2003). EBs target numerous other +TIPs to the tips of polymerizing microtubules (Kumar and Wittmann, 2012). In mammalian cells the EB family is represented by EB1, EB2 and EB3. EB proteins have been involved in axon extension, guidance and the regulation of the axon initial segment (Cammarata et al., 2016; Leterrier et al., 2011). Here we focus on the current understanding of the role of EB proteins in axon initiation and branching. A major theme is that EB proteins serve as scaffolds for +TIP proteins that in turn serve to regulate neuronal morphogenesis and actin filament-microtubule interactions, which are discussed in relation to axon/minor process initiation and branch formation below.

4.1.1. EB-associated +TIP proteins

4.1.1.1. Drebrin

Beyond the function of drebrin in dendritic spines (Sekino et al., 2007), several studies have demonstrated its role in process formation and collateral branching as a microtubule-actin crosstalk protein. Drebrin is an actin filament side-binding protein. Drebrin exhibits two actin filament binding domains. One of these domains is cryptic but uncovered by Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation (Worth et al., 2013). Thus, when not phosphorylated drebrin can bind actin filaments through its available binding domain. However, following phosphorylation drebrin is now enabled to promote the formation of actin filament bundles (e.g., as observed in filopodia). Consistently, drebrin is required for filopodia formation in neurons, and overexpression of drebrin promotes formation of filopodia (Dun et al., 2012; Geraldo et al., 2008; Ketschek et al., 2016). Drebrin binds EB3 although it does not track microtubule plus ends as a +TIP protein (Geraldo et al., 2008), and Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation promotes its binding to EB3 (Worth et al., 2013). Overall, drebrin colocalizes with actin filaments throughout neurons. However, within filopodia it is largely restricted to the proximal segment of filopodia through a myosin II-dependent mechanism (Geraldo et al., 2008; Ketschek et al., 2016). Thus, drebrin is poised to serve as a dynamic crosslinker between EB-decorated microtubule plus ends and actin filaments.

As noted in the introduction, the targeting of microtubules into filopodia formed at the cell body is an important step in the initial formation of minor processes and axons. Disruption of the interaction between EB3 and drebrin results in decreased numbers of minor processes (Geraldo et al., 2008). Conversely, overexpression of drebrin increases the number of filopodia formed by cell bodies, the targeting of microtubules into filopodia, and process formation. A similar mechanism is operative in the formation of axon branches (Ketschek et al., 2016). Overexpression and depletion of drebrin increases and decreases the formation of axonal filopodia and branches, respectively (Dun et al., 2012; Ketschek et al., 2016). As with filopodia generated from the cell body, overexpression of drebrin increases the targeting of microtubules into axonal filopodia, a necessary step in collateral branch formation (Ketschek et al., 2016). Drebrin is involved in the formation of the actin filament bundles of axonal filopodia from precursor actin filament patches (Ketschek et al., 2016), consistent with its role in promoting filament bundling. Drebrin also contributes to the formation and elaboration of the actin patches prior to emergence of filopodia. A switch in the phosphorylation state of drebrin may underlie its function in regulating actin patches, which consist of meshworks of filaments (Spillane et al., 2011), to its function in promoting the emergence of filopodial actin filament bundles from patches. Collectively, these studies identify drebrin as a major determinant of the actin filament dependent targeting of microtubule plus tips into filopodia. Since Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation increases both the actin bundling and EB3 binding activities of drebrin, a single phosphorylation event may be sufficient to generate a conformation of drebrin that functionally links actin filament bundle formation to the promotion of the physical association of EB3 decorated microtubule tips within the same population of actin filaments.

4.1.1.2 CLIP-170

The microtubule end-binding protein cytoplasmic linker protein CUP-170 is a +TIP protein that binds to the C termini of EBs through a CAP-Gly domain (Weisbrich et al., 2007) and tracks microtubule plus ends. CLIP-170 in turn binds IQGAP, a downstream effector of Rac1 and Cdc42 GTPases (Fukata et al., 2002a). Depletion of IQGAP3 results in impaired formation of processes from the cell bodies of neuron-like PC12 cells (Wang et al., 2007). Thus, the dynamics of microtubule plus tips may target IQGAP3 to regions of the cell body where the activity of Rac1/Cdc42 can then exert effects on the actin cytoskeleton through IQGAP3. As noted previously, microtubule tips in growth cones can drive the local polymerization of actin filaments in a Rac1 -dependent manner (Grabham et al., 2003). Collectively, these studies suggest that the EB3/CLIP-170/IQGAP3 complex at the tips of microtubules is a major component of this mechanism. The role of the CLIP-170 based mechanism may be to decrease the formation of actin arcs (Neukirchen and Bradke, 2011b), which as noted in the introduction serve to restrain microtubule advance into growth cones. Whether CLIP-170 contributes to axon branching remains to be determined.

4.1.1.3 The Cytoplasmic Linker Protein-Associated Proteins (CLASPs)

The CLASPs family of +TIPs binds CLIPs and EBs (van de Willige et al., 2016). CLASP2 is involved in axon outgrowth and neuronal polarity by acting as a local stabilizer of microtubules (Beffert et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2004). CLASPs are involved in the regulation of EB protein binding to microtubule plus tips albeit not through direct interactions (Grimaldi et al., 2014). CLASP1 and CLASP2 interact with actin filaments functioning as actin/microtubule crosslinkers at the initial stages of actin-microtubule interaction in the lamellipodia of Xenopus primary fibroblasts and in the filopodia of Xenopus spinal cord neurons (Tsvetkov et al., 2007). CLASP2 binding with both microtubules and actin is modulated by Abl phosphorylation, and Abl-induced phosphorylation of CLASP2 modulates its localization as well as the distribution of F-actin structures in spinal cord growth cones (Engel et al., 2014). Depletion of CLASP1 reduces axon outgrowth in Xenopus spinal cord neurons. CLASP1-depleted growth cones exhibited reduced microtubule advance into growth cone filopodia and the reorganization of actin filament structures, indicating an important role of CLASP1 in actin–microtubule interactions (Marx et al., 2013). However, although implicated in axon extension the roles of CLASPs in axon initiation and branching remain to the determined. Given that CLASPs are binding partners of CLIPs it seems likely they may have similar roles.

4.1.1.4 Spectraplakins

Spectraplakins represent a large family of +TIPs multi-domain proteins that can interact with EBs. These proteins exhibit F-actin binding sites in their calponin homology domains, microtubule binding sites in their C-terminal regions, and can also associate with intermediate filaments (Suozzi et al., 2012).The family consists of many differentially spliced forms with differing functions. Using an engineered minimal version of ACF7, a spectraplakin that binds actin filaments and microtubules, Preciado-Lopez et al. (2014) provide evidence these proteins can promote the alignment of microtubules with actin filament bundles (Preciado Lopez et al., 2014). Shot stop, the close Drosophila homologue of ACF7, acts as an actin-microtubule linker during axonal growth (Sanchez-Soriano et al., 2009; Sanchez-Soriano et al., 2010). ACF7 and Short stop also regulate the actin cytoskeleton through their ability to increase the number of filopodia (Sanchez-Soriano et al., 2009), although the effects on filopodia do not depend on an actin-microtubule linker function.

Microtubule-actin crosslinking factor 1 (MACF1/ACF7) was recently reported to promote the branching of both dendrites and axons in cortical neurons (Ka and Kim, 2015). Genetic deletion of MACF1 resulted in a decrease in net actin filament levels at growth cones, although the effect on the axonal filament cytoskeleton was not considered. In vivo and in vitro deletion of MACF1 resulted in increased numbers of dendrites emerging from the cell body, indicating that in contrast to its positive contribution to axon branching MACF1 may have an antagonist role in the initiation of minor processes or dendritic differentiation. Interestingly, Alves-Silva et al. (2012) report that depletion of ACF7 from cortical neurons results in the splaying of the axonal microtubule array. As noted in Section 1.2, the splaying of microtubules at sites of branching is an important aspect of the branching mechanism (Alves-Silva et al., 2012) (see Figure 2). It remains to be determined if ACF7 or related proteins may be locally regulated during the early stages of collateral branching. Spektraplakins are poised to be important regulators of neuronal morphogenesis at multiple stages. Given the large number of proteins in this family it will be of interest to untangle the roles of individual family members in different neuronal types and at different stages of development.

4.1.1.5. Neuron navigator 1 (Nav1)

Nav1 binds EB1 and also the Rac1/RhoG activator guanine exchange factor Trio and knockdown of Nav1 in N1E-115 neuron-like cells results in decrease number of processes formed by cell bodies (van Haren et al., 2014). The binding of Nav1 to Trio increases its activation of Rac1, providing a mechanistic link to how Nav1 can regulate actin filament dynamics. Nav1 can compete with CLIP-170 for binding to EB proteins and overexpression in non-neuronal cells results in the formation of processes (van Haren et al., 2009). Since as noted previously CLIP-170 binds the Rac1 effector IQGAP, competitive binding of Nav1 and CLIP-170 may serve to determine activation of Rac1 relative to selection of Rac1 downstream effectors that can mediate the effects of microtubule plus tip mediated Rac1 functions. Alternatively, the relative proportions of Nav1 and CLIP-170 on microtubule plus ends may act to promote Rac1 activity while also providing a downstream effector in close proximity. Although a role for Nav1 in branching has not yet been determined, Rac1 is an important mediator of actin filament dynamics and organization during branching (Spillane and Gallo, 2014) and it seems likely a role will emerge.

4.1.1.6. Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)

APC binds EB proteins and targets to microtubule plus ends (Slep et al., 2005) and also interacts with the Rac1 effector IQGAP1 (Watanabe et al., 2004). Genetic deletion of APC increases the number of axon branches without impacting the number of axons or dendrites formed per neuron (Chen et al., 2011; Yokota et al., 2009). This observation is at odds with the role of Rac1 in promoting branch formation. However, deletion of APC also increases the dynamics of the microtubule cytoskeleton (Yokota et al., 2009), an effect that may promote the microtubule dependent aspect of branching. Furthermore, as other +TIP proteins can promote Rac1 activity the loss of APC function vis-à-vis Rac1 may not be dominant in branching, and APC may have additional binding partners yet to be considered. APC was recently shown to bind a subset of mRNAs and target them into axons (Preitner et al., 2014). It is possible that depletion of APC may prevent the targeting or translation of mRNAs that are inhibitory to axon branching.

5. Additional regulators of cytoskeletal crosstalk and organization

5.1. Septins

Septins are GTP-binding proteins that form homo and heteropolymers capable of associating with membranes and the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton (Spiliotis and Nelson, 2003). Septin 6 and 7 have been implicated in axon collateral branching through regulation of the axonal cytoskeleton (Ageta-Ishihara et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2012). Septin 6, but not 7, was found to regulate the formation of axonal filopodia from axonal actin patches. In contrast, septin 7 was found to increase the percentage of axonal filopodia containing microtubules. The distribution of septin 7 along axons and within filopodia is consistent with a role for septin 7 in guiding polymerizing tips into axonal filopodia (Figure 2). Septin 7 specifically localizes to the base of filopodia, placing it in proximity to microtubule plus tips polymerizing along the axon. Septin 7 has also been found to negatively control the levels of acetylated tubulin in axons (Ageta-Ishihara et al., 2013). Tubulin acetylation can regulate aspects of the interactions of microtubule based motors and other microtubule binding proteins (Song and Brady, 2015) suggesting potential downstream mechanisms. Little is known of the roles of septins in axon/minor process initiation but expression of a GTPase binding mutant of septin 2 impairs the formation of processes from NGF stimulated PC12 cells (Vega and Hsu, 2003).

5.2. Collapsin response mediator proteins (CRMPs)

The five different CRMP family members are expressed in a brain region and developmental stage dependent manner (Quach et al., 2015). CRMP1-5 all bind both tubulin and actin proteins by GST-pulldown assay, and by immunocytochemistry using anti-panCRMP CRMPs colocalize with both actin and tubulin antibody staining (Yang et al., 2015). CRMP proteins thus likely associate with the soluble forms of actin and tubulin and may coregulate their availability for polymerization. Consistent with this notion CRMP2 promotes tubulin polymerization (Fukata et al., 2002b). Overexpression of CRMP2 promotes process formation from N1E-115 neuron-like cells (Fukata et al., 2002b) and genetic deletion of CRMP3 results in the failure of hippocampal neurons to elaborate minor processes (Quach et al., 2013). In contrast, overexpression of CRMP5 inhibits process formation from PC12 cells through decreasing the interactions between CRMP2 and tubulin (Brot et al., 2010; Brot et al., 2014). These studies determine CRMP proteins regulate the initial formation of processes from cell bodies and they exhibit complex relationships between family members. It will be of interest to further explore the role of CRMPs binding actin in the regulation of the actin filament cytoskeleton.

Fukata et al (2002) report that overexpression of CRMP2 increases the length and branching of hippocampal neuron axons (Fukata et al., 2002b). However, the relative increase in the length of axons scales proportionally with the relative increase in the number of axon branches, indicating the increased number of branches measured is likely reflective of increased axon lengths and not an effect on the initiation of branches. Thus, the issue of whether CRMP2 is involved in axon branching may benefit from further investigation.

5.3 Doublecortin (DCX)

DCX recognizes and stabilizes 13-protofilament microtubules (Brouhard and Rice, 2014) and associates with microtubules at axonal actin-rich protrusive structures (Tint et al., 2009). Dcx promotes bundling and crosslinking of microtubules and actin filaments that is further enhanced by the association of doublecortin with neurabin II, an actin filament binding protein (Tsukada et al., 2005). Depletion of DCX in hippocampal culture neurons inhibits the formation of “actin waves” that can serve as precursors to the formation of axon branches by hippocampal neurons (Flynn et al., 2009; Tint et al., 2009). Actin waves are lamellipodial structures that migrate anterogradely along the axon (Ruthel and Banker, 1998). Interestingly, the localization of waves correlates with transported accumulations of doublecortin (Tint et al., 2009). In axons from mice mutant for Dcx the distribution of actin filaments is increased around the cell body and decreased in the neurites and growth cones (Fu et al., 2013). These studies indicate that in hippocampal neurons Dcx may serve to crosslink the actin filament and microtubule cytoskeleton during branch formation involving axonal actin waves. Knockdown of Dcx in cortical neurons increases axon collateral branching (Li et al., 2014). Similarly, in cerebellar neurons knockdown of Dcx promotes axon branching (Bilimoria et al., 2010). However, whether the branches monitored arose through collateral branching and not growth cone splitting was not specifically addressed.

6. Implications for the mechanism that targets microtubules into filopodia and the subsequent maturation of processes and branches

The studies reviewed above suggest a model for the targeting of microtubules into filopodia, a conserved step between the initiation of processes from cell bodies and the formation of axon collateral branches (Figure 2). Microtubules plus tips recruit EB proteins, which in turn recruit EB-binding +TIP proteins and their binding partners. These molecular complexes endow the microtubule plus tip with biochemical mechanisms that in turn can regulate the actin filament cytoskeleton. The reviewed studies indicate that regulation of Rac1-based mechanisms by microtubule plus tips is a common feature of +TIP proteins. Septin 7 localizes specifically at the base of filopodia and serves to promote the association of microtubule plus tips with actin filaments. Drebrin targets to the base of filopodia and further distally along the filopodial actin filament bundle, and promotes the entry of plus tips into filopodia. It seems likely that drebrin then continues to promote the association of the captured microtubule tip with the filopodial actin filament bundle, likely through the phosphorylation based mechanism discussed in section 4.1.1.1. Although microtubule plus tips undergo depolymerization within filopodia with relatively high frequencies, and the same filopodium can be repeatedly targeted by plus tips, sometimes a microtubule becomes stabilized in the filopodium (Dent and Kalil, 2001; Gallo and Letourneau, 1999; Ketschek et al., 2016). The mechanism that stabilizes microtubules in filopodia is not currently clear. However, the initial stabilization of a microtubule into a filopodium could have multiple consequences: (1) It may serve as an additional guide for other microtubules to target into the filopodium through microtubule-microtubule associations, and (2) it may serve to provide an initial scaffold for other microtubules to populate and be retained within the filopodium. When microtubule tips depolymerize the EB-complexes are predicted to come off the microtubule releasing the +TIP proteins locally. Following multiple instances of tip depolymerization this may result in the accumulation of Rac1 and its effectors within the filopodium. This may result in the buildup of a local “tinder box” of Rac1 activity in the filopodium that could be “ignited” by a later microtubule plus tip resulting is sufficient activation of the Rac1-based mechanism driving the formation of a lamellipodium and reorganization of the filopodial actin filament bundle (Figure 2C). Consistent with this notion, the IQGAP proteins found to associate with +TIPs serve to drive Rac1-mediated formation of lamellipodia (Watanabe et al., 2015). I addition, septins can form diffusion barriers promoting separation between distinct subcellular domains (e.g., a filopodium or a dendritic spine; (Bridges and Gladfelter, 2015; Reiter et al., 2012)) thereby possibly contributing to the spatial restriction of the localization of cellular mechanisms. This could establish the initial polarity required for subsequent maturation of the nascent collateral branch or process from the cell body. This last aspect of the mechanism is speculative, but lends itself to experimental investigation.

7. Conclusions

This review presents the current evidence for the crosstalk and interdependent organization of the actin filament and microtubule cytoskeleton during the initiation of processes from cell bodies and the collateral branching of axons. These two aspects of neuronal morphogenesis share many similarities, in particular as they relate to the requirement of the orchestration of the cytoskeleton in space and time. The field has advanced significantly since the initial proposal that actin filament bundles in growth cone filopodia may be able to capture and guide microtubules (Gordon-Weeks, 1991). It is now clear that microtubule plus tips are decorated with a variety of proteins that can mediate interactions between the two cytoskeletal systems, and that through these proteins microtubule plus tips can regulate the dynamics of actin filaments. Canonical MAPs have also emerged as regulators of cytoskeletal interactions. The roles of cytoskeletal cross-regulators can be promoting or inhibitory. Ultimately, to fully understand the complexity of cytoskeletal cross-regulation the full spectrum of interactions and interactors will need to be address in space and time during the multiple steps in the formation of processes and collateral branches. The process of axon branching is regulated by both branch inducing and repressing extracellular signals (Gibson and Ma, 2011; Kalil and Dent, 2014; Schmidt and Rathjen, 2010). Elucidating the mechanisms used by these signals to control the interactions between actin filaments and the cytoskeleton will add a new layer to the understanding of axon branching. Axon branching is not only of relevance to the developmental morphogenesis of the nervous system but it is also a major aspect of injury-induced adult neural plasticity in the adult (Onifer et al., 2011). Whether the lessons learned from the analysis of embryonic or early developmental systems will apply to adult neurons remains a mostly unchartered frontier.

The cytoskeleton underlies neuronal biomechanics. The generation of protrusive force by actin filament polymerization is recognized as fundamental to the initiation and elongation of filopodia, and required to counter the tension in the plasma membrane. Similarly, in specific experimental contexts, microtubule polymerization can also counter membrane tension and result in the generation of cellular protrusions or drive the elongation of the axon in the absence of actin filaments (Goldberg and Burmeister, 1992; Jones et al., 2006). However, no studies to date have addressed the biomechanics of axon initiation and branching. It seems likely similar principles will apply, but the field needs pioneering studies. Given myosin II generated intracellular forces can regulate the organization of the microtubule cytoskeleton in growth cones and along axons, it seems likely the regulation of substratum attachment through myosin II dependent contact will have a role in branching. In growth cones, substratum attachment regulates actin retrograde flow (Kerstein et al., 2015). Myosin II seems well poised to serve a similar function in individual filopodia that exhibit substratum attachment points at both the site of initiation and along their lengths (Steketee et al., 2001; Steketee and Tosney, 2002). Structural interactions between actin filaments and microtubules are also likely to contribute to cellular biomechanics, but again this issue has not been addressed. Consideration of this issue will require approaches to specifically manipulate these interactions, without affecting other functions of the relevant proteins (e.g., their role in signaling or scaffolding). Similarly, consideration of possible roles for +TIP proteins in regulating neuronal biomechanics will require specific experimental approaches and many controls addressing the multitude of functions served by these proteins. In conclusion, the role of cytoskeletal crosslinks and crosstalk in regulating biomechanics is likely to be fruitful venue of continued investigation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH award NS078030 (GG).

Referenced Literature

- Ageta-Ishihara N, et al. Septins promote dendrite and axon development by negatively regulating microtubule stability via HDAC6-mediated deacetylation. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2532. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves-Silva J, et al. Spectraplakins promote microtubule-mediated axonal growth by functioning as structural microtubule-associated proteins and EB1-dependent +TIPs (tip interacting proteins) J Neurosci. 2012;32:9143–58. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0416-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold DB, Gallo G. Structure meets function: actin filaments and myosin motors in the axon. J Neurochem. 2014;129:213–20. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnat M, et al. The GSK3-MAP1B pathway controls neurite branching and microtubule dynamics. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2016;72:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearce EA, Erdogan B, Lowery LA. TIPsy tour guides: how microtubule plus-end tracking proteins (+TIPs) facilitate axon guidance. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:241. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beffert U, et al. Microtubule plus-end tracking protein CLASP2 regulates neuronal polarity and synaptic function. J Neurosci. 2012;32:13906–16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2108-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bershadsky AD, Vaisberg EA, Vasiliev JM. Pseudopodial activity at the active edge of migrating fibroblast is decreased after drug-induced microtubule depolymerization. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1991;19:152–8. doi: 10.1002/cm.970190303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilimoria PM, et al. A JIP3-regulated GSK3beta/DCX signaling pathway restricts axon branching. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16766–76. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1362-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouquet C, et al. Microtubule-associated protein 1B controls directionality of growth cone migration and axonal branching in regeneration of adult dorsal root ganglia neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7204–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2254-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouquet C, et al. MAP1B coordinates microtubule and actin filament remodeling in adult mouse Schwann cell tips and DRG neuron growth cones. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;36:235–47. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges AA, Gladfelter AS. Septin Form and Function at the Cell Cortex. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:17173–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.634444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brot S, et al. CRMP5 interacts with tubulin to inhibit neurite outgrowth, thereby modulating the function of CRMP2. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10639–54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0059-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brot S, et al. Collapsin response-mediator protein 5 (CRMP5) phosphorylation at threonine 516 regulates neurite outgrowth inhibition. Eur J Neurosci. 2014;40:3010–20. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouhard GJ, Rice LM. The contribution of alphabeta-tubulin curvature to microtubule dynamics. J Cell Biol. 2014;207:323–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201407095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugg B, Reddy D, Matus A. Attenuation of microtubule-associated protein 1B expression by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides inhibits initiation of neurite outgrowth. Neuroscience. 1993;52:489–96. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90401-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette DT, et al. Filopodial actin bundles are not necessary for microtubule advance into the peripheral domain of Aplysia neuronal growth cones. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1360–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette DT, et al. Myosin II activity facilitates microtubule bundling in the neuronal growth cone neck. Dev Cell. 2008;15:163–9. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caceres A, Mautino J, Kosik KS. Suppression of MAP2 in cultured cerebellar macroneurons inhibits minor neurite formation. Neuron. 1992;9:607–18. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammarata GM, Bearce EA, Lowery LA. Cytoskeletal social networking in the growth cone: How +TIPs mediate microtubule-actin cross-linking to drive axon outgrowth and guidance. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2016 doi: 10.1002/cm.21272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, et al. Adenomatous polyposis coli regulates axon arborization and cytoskeleton organization via its N-terminus. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cueille N, et al. Characterization of MAP1B heavy chain interaction with actin. Brain Res Bull. 2007;71:610–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dajas-Bailador F, et al. microRNA-9 regulates axon extension and branching by targeting Map1b in mouse cortical neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:697–699. doi: 10.1038/nn.3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehmelt L, et al. The role of microtubule-associated protein 2c in the reorganization of microtubules and lamellipodia during neurite initiation. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9479–90. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-29-09479.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehmelt L, Halpain S. The MAP2/Tau family of microtubule-associated proteins. Genome Biol. 2005;6:204. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-6-1-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehmelt L, et al. A microtubule-based, dynein-dependent force induces local cell protrusions: Implications for neurite initiation. Brain Cell Biol. 2006;35:39–56. doi: 10.1007/s11068-006-9001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent EW, Kalil K. Axon branching requires interactions between dynamic microtubules and actin filaments. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9757–69. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09757.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent EW, Gertler FB. Cytoskeletal dynamics and transport in growth cone motility and axon guidance. Neuron. 2003;40:209–27. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00633-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent EW, et al. Netrin-1 and semaphorin 3A promote or inhibit cortical axon branching, respectively, by reorganization of the cytoskeleton. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3002–12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4963-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent EW, et al. Filopodia are required for cortical neurite initiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1347–59. doi: 10.1038/ncb1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dun XP, et al. Drebrin controls neuronal migration through the formation and alignment of the leading process. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2012;49:341–50. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel U, et al. Abelson phosphorylation of CLASP2 modulates its association with microtubules and actin. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2014;71:195–209. doi: 10.1002/cm.21164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn KC, et al. Growth cone-like waves transport actin and promote axonogenesis and neurite branching. Dev Neurobiol. 2009;69:761–79. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn KC, et al. ADF/cofilin-mediated actin retrograde flow directs neurite formation in the developing brain. Neuron. 2012;76:1091–107. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forscher P, Smith SJ. Actions of cytochalasins on the organization of actin filaments and microtubules in a neuronal growth cone. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1505–16. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X, et al. Doublecortin (Dcx) family proteins regulate filamentous actin structure in developing neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:709–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4603-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukata M, et al. Rac1 and Cdc42 capture microtubules through IQGAP1 and CLIP-170. Cell. 2002a;109:873–85. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00800-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukata Y, et al. CRMP-2 binds to tubulin heterodimers to promote microtubule assembly. Nat Cell Biol. 2002b;4:583–91. doi: 10.1038/ncb825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo G. Involvement of microtubules in the regulation of neuronal growth cone morphologic remodeling. J Neurobiol. 1998;35:121–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo G, Letourneau PC. Different contributions of microtubule dynamics and transport to the growth of axons and collateral sprouts. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3860–73. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-03860.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo G. Actin turnover is required to prevent axon retraction driven by endogenous actomyosin contractility. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2002;158:1219–1228. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200204140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo G. The cytoskeletal and signaling mechanisms of axon collateral branching. Dev Neurobiol. 2011;71:201–20. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo G. Mechanisms underlying the initiation and dynamics of neuronal filopodia: from neurite formation to synaptogenesis. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2013;301:95–156. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407704-1.00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly A, et al. A dynamic formin-dependent deep F-actin network in axons. J Cell Biol. 2015;210:401–17. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201506110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraldo S, et al. Targeting of the F-actin-binding protein drebrin by the microtubule plus-tip protein EB3 is required for neuritogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1181–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson DA, Ma L. Developmental regulation of axon branching in the vertebrate nervous system. Development. 2011;138:183–95. doi: 10.1242/dev.046441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg DJ, Burmeister DW. Microtubule-based filopodium-like protrusions form after axotomy. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4800–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-12-04800.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Weeks PR. Evidence for microtubule capture by filopodial actin filaments in growth cones. Neuroreport. 1991;2:573–6. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabham PW, Reznik B, Goldberg DJ. Microtubule and Rac 1-dependent F-actin in growth cones. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3739–48. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith LM, Pollard TD. Evidence for actin filament-microtubule interaction mediated by microtubule-associated proteins. J Cell Biol. 1978;78:958–65. doi: 10.1083/jcb.78.3.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi AD, et al. CLASPs are required for proper microtubule localization of end-binding proteins. Dev Cell. 2014;30:343–52. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenraad CC, Bradke F. Control of neuronal polarity and plasticity–a renaissance for microtubules? Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:669–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, et al. Septin-driven coordination of actin and microtubule remodeling regulates the collateral branching of axons. Curr Biol. 2012;22:1109–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SL, Selzer ME, Gallo G. Developmental regulation of sensory axon regeneration in the absence of growth cones. Journal of neurobiology. 2006;66:1630–45. doi: 10.1002/neu.20309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ka M, Kim WY. Microtubule-Actin Crosslinking Factor 1 Is Required for Dendritic Arborization and Axon Outgrowth in the Developing Brain. Mol Neurobiol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9508-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalil K, Dent EW. Branch management: mechanisms of axon branching in the developing vertebrate CNS. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:7–18. doi: 10.1038/nrn3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstein PC, Nichol RHT, Gomez TM. Mechanochemical regulation of growth cone motility. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:244. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketschek A, et al. Nerve Growth Factor Promotes Reorganization of the Axonal Microtubule Array at Sites of Axon Collateral Branching. Developmental Neurobiology. 2015;75:1441–1461. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketschek A, et al. Drebrin Coordinates the Actin and Microtubule Cytoskeleton During the Initiation of Axon Collateral Branches. Dev Neurobiol. 2016 doi: 10.1002/dneu.22377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketschek AR, Jones SL, Gallo G. Axon extension in the fast and slow lanes: substratum-dependent engagement of myosin II functions. Dev Neurobiol. 2007;67:1305–20. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kevenaar JT, Hoogenraad CC. The axonal cytoskeleton: from organization to function. Front Mol Neurosci. 2015;8:44. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2015.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijpers M, Hoogenraad CC. Centrosomes, microtubules and neuronal development. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;48:349–58. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Wittmann T. +TIPs: SxIPping along microtubule ends. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:418–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwei SL, et al. Differential interactions of MAP2, tau and MAP5 during axogenesis in culture. Neuroreport. 1998;9:1035–40. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199804200-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeClerc N, et al. Process formation in Sf9 cells induced by the expression of a microtubule-associated protein 2C-like construct. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:6223–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, et al. The microtubule plus end tracking protein Orbit/MAST/CLASP acts downstream of the tyrosine kinase Abl in mediating axon guidance. Neuron. 2004;42:913–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leterrier C, et al. End-binding proteins EB3 and EB1 link microtubules to ankyrin G in the axon initial segment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:8826–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018671108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TL, Jr, Courchet J, Polleux F. Cell biology in neuroscience: Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying axon formation, growth, and branching. J Cell Biol. 2013;202:837–48. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201305098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, et al. MicroRNA-29a modulates axon branching by targeting doublecortin in primary neurons. Protein Cell. 2014;5:160–9. doi: 10.1007/s13238-014-0022-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CH, et al. Myosin drives retrograde F-actin flow in neuronal growth cones. Neuron. 1996;16:769–82. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeder CI, Shen K, Hoogenraad CC. Axon and dendritic trafficking. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2014;27C:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx A, et al. Xenopus cytoplasmic linker-associated protein 1 (XCLASP1) promotes axon elongation and advance of pioneer microtubules. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:1544–58. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-08-0573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimori-Kiyosue Y, Shiina N, Tsukita S. The dynamic behavior of the APC-binding protein EB1 on the distal ends of microtubules. Curr Biol. 2000;10:865–8. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00600-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan R, John A. Microtubule-associated proteins as direct crosslinkers of actin filaments and microtubules. IUBMB Life. 2015;67:395–403. doi: 10.1002/iub.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neukirchen D, Bradke F. Neuronal polarization and the cytoskeleton. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011a;22:825–33. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neukirchen D, Bradke F. Cytoplasmic linker proteins regulate neuronal polarization through microtubule and growth cone dynamics. J Neurosci. 2011b;31:1528–38. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3983-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onifer SM, Smith GM, Fouad K. Plasticity after spinal cord injury: relevance to recovery and approaches to facilitate it. Neurotherapeutics. 2011;8:283–93. doi: 10.1007/s13311-011-0034-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer RS, Halpain S. Phosphorylation-dependent localization of microtubule-associated protein MAP2c to the actin cytoskeleton. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3573–87. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.10.3573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrotti B, Islam K. Dephosphorylated but not phosphorylated microtubule associated protein MAP1B binds to microfilaments. FEBS Lett. 1996;388:131–3. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00520-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez F, et al. CLIP-170 highlights growing microtubule ends in vivo. Cell. 1999;96:517–27. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80656-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preciado Lopez M, et al. Actin-microtubule coordination at growing microtubule ends. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4778. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preitner N, et al. APC is an RNA-binding protein, and its interactome provides a link to neural development and microtubule assembly. Cell. 2014;158:368–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quach TT, et al. Mapping CRMP3 domains involved in dendrite morphogenesis and voltage-gated calcium channel regulation. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:4262–73. doi: 10.1242/jcs.131409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quach TT, et al. CRMPs: critical molecules for neurite morphogenesis and neuropsychiatric diseases. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:1037–45. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter JF, Blacque OE, Leroux MR. The base of the cilium: roles for transition fibres and the transition zone in ciliary formation, maintenance and compartmentalization. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:608–18. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochlin MW, Dailey ME, Bridgman PC. Polymerizing microtubules activate site-directed F-actin assembly in nerve growth cones. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:2309–27. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.7.2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger B, et al. MAP2c, but not tau, binds and bundles F-actin via its microtubule binding domain. Curr Biol. 2004;14:363–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruthel G, Banker G. Actin-dependent anterograde movement of growth-cone-like structures along growing hippocampal axons: a novel form of axonal transport? Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1998;40:160–73. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1998)40:2<160::AID-CM5>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainath R, Gallo G. Cytoskeletal and signaling mechanisms of neurite formation. Cell Tissue Res. 2015;359:267–78. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-1955-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Soriano N, et al. Mouse ACF7 and drosophila short stop modulate filopodia formation and microtubule organisation during neuronal growth. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2534–42. doi: 10.1242/jcs.046268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]