Abstract

The impact of integrated reproductive health and HIV services on HIV testing and counseling (HTC) uptake was assessed among 882 Kenyan family planning clients using a nonrandomized cohort design within six intervention and six “comparison” facilities. The effect of integration on HTC goals (two tests over two years) was assessed using conditional logistic regression to test four “integration” exposures: a training and reorganization intervention; receipt of reproductive health and HIV services at recruitment; a functional measure of facility integration at recruitment; and a woman's cumulative exposure to functionally integrated care across different facilities over time. While recent receipt of HTC increased rapidly at intervention facilities, achievement of HTC goals was higher at comparison facilities. Only high cumulative exposure to integrated care over two years had a significant effect on HTC goals after adjustment (aOR 2.94, 95%CI 1.73‐4.98), and programs should therefore make efforts to roll out integrated services to ensure repeated contact over time.

The integration of reproductive health (RH) and HIV services is hypothesized to have multiple service‐ and health‐related benefits. In addition to increasing cost‐effectiveness, it is expected that the co‐location of services under one roof, or within one consultation room, will minimize problematic referral processes and increase service uptake, and thus impact RH‐ and HIV‐related behaviors and outcomes (Askew and Berer 2003; Sibide and Buse 2009). Robust evidence on these potential benefits, however, is lacking. A Cochrane review on the impacts of all types of integrated primary health care found no evidence that more‐integrated services improve health‐care delivery or health status (Dudley and Garner 2011). Reviews on the integration of RH and HIV services, specifically, conclude that research evidence on outcomes is lacking, with few studies adequately defining and measuring integrated services, or comparing integrated with stand‐alone health services (Kennedy et al. 2010; Lindegren et al. 2012; Wilcher et al. 2013).

One potential benefit of integrated care is increased utilization of the individual component health services. Increasing the uptake of HIV testing and counseling (HTC) is a critical public health goal, since the proportion of adults who know their HIV status rarely exceeds 50 percent in most high‐ and medium‐HIV prevalence settings (UNAIDS 2013 and 2014b). Annual testing rates are even lower, with national surveys reporting only around one‐fifth of women and men receiving a test in the past year (Staveteig et al. 2013). Knowledge of HIV status is an essential prerequisite to accessing antiretroviral therapy (ART) for people living with HIV (PLHIV), and the need to scale up testing has been asserted in new “90‐90‐90” global targets, aiming to have 90 percent of PLHIV knowing their status, 90 percent on sustained ART, and 90 percent with viral suppression by the year 2020 (UNAIDS 2014a). Knowledge of status also contributes to HIV prevention, not only through access to treatment and associated viral suppression, but through reductions in the risk of perinatal and onward sexual transmission (Denison et al. 2008; Kennedy et al. 2013).

Repeated testing every 6 to 12 months has been recommended by the World Health Organization since 2007 for those at higher risk of HIV exposure. In Kenya, where HIV prevalence is estimated at 6.1 percent (UNAIDS 2013) and risk of exposure is high, repeat annual testing for those who test negative has been recommended since 2010 (NASCOP 2010). However, a national household survey indicated that only 29 percent of women and 23 percent of men have tested in the past 12 months (Staveteig et al. 2013). Integration between RH and HIV services has been rolled out nationally as a strategy to promote HIV testing by the Kenyan Ministry of Health (MOPHS 2009 and 2012).

Multiple strategies have been designed and evaluated to promote uptake of HTC within generalized epidemics. Provider‐initiated testing and counseling for HIV is one intervention that has shown proven impact on HIV testing uptake when services were integrated within antenatal care, primary care, STI, and TB services (Pope et al. 2008; Leon et al. 2010; Kennedy et al. 2013). A systematic review on the implementation of provider‐initiated testing and counseling in sub‐Saharan Africa, however, found challenges with the approach, with levels of test offering and acceptance varying markedly by study setting (Roura et al. 2013). For maternal and child health (MCH) programs, promoting HTC within antenatal care has remained a focus as it is an essential strategy to prevent mother‐to‐child transmission (Baggaley et al. 2012), and it is being increasingly promoted through the roll‐out of the Option B+ regimen (Herlihy et al. 2015). Documentation of the integration and promotion of HTC within family planning (FP) services is more limited. FP clients are an important target group for testing since they are sexually active and usually not current condom users. Evidence on the effectiveness of integrating HTC into FP services is limited. One cross‐sectional analysis of FP clinic records in Ethiopia compared integration at provider, room, and facility levels (i.e., assessing whether HTC uptake differed when offered by the same provider, in the same room, or in the same building as the FP service) (Bradley et al. 2008). Higher HIV testing uptake was found in facilities with room‐ and provider‐level integration. In Kenya's Central Province, an uncontrolled pre/post‐test comparing an “integrated” FP‐HTC model (on‐site testing) with a “referral” model found increases in discussion of HIV during consultations and increases in HIV testing acceptance following a training and counseling support intervention, with testing acceptance higher in the “on‐site” testing group (Liambila et al. 2009). However, no attempt was made to control for any selection bias in the two study populations and the evaluation was conducted over a short period (ten months).

In their Cochrane review on integrated care, Dudley and Garner (2011) underline the complexity in the definition and measurement of integrated care, and the need for clear and transparent documentation of any integrated intervention being evaluated. In general, most interventions involve some degree of care reorganization, but others have merely provided training and/or the provision of equipment (Kennedy et al. 2010; Dudley and Garner 2011). Most fail to assess whether integrated care (linked provision by one provider, or at one visit) is actually being provided to the client, and outcomes may be associated with interventions that were not fully implemented.

In this article, we assess the impact of integrating HIV and FP services on the HTC uptake of FP clients in Central Province, Kenya and specifically test the effect of four different exposure definitions of integrated care: an intervention involving training and reorganization; receipt of both RH and HIV services at recruitment; a functional measure of facility integration at recruitment; and a woman's cumulative exposure to functionally integrated care across different facilities over time. The research was conducted as part of the Integra Initiative, a large‐scale evaluation of RH‐HIV service integration in Kenya and Swaziland. The Integra Initiative is a registered nonrandomized trial.1 Integra aims to evaluate the effect of service integration within FP and postnatal‐care settings and is comprised of multiple quantitative and qualitative components, including household surveys, cohort studies, facility surveys, and qualitative process evaluation (Warren et al. 2012).

METHODS

Study Setting and Design

Integra was implemented in public health facilities in Central and Eastern Provinces in Kenya, and in three regions in Swaziland. Our article focuses on findings from Central Province in Kenya, where an intervention was introduced into six facilities (health centers and hospitals) to strengthen the provision of integrated FP‐HIV services. Compared to the national average, at the time of the research the region had a higher modern contraceptive prevalence (46 percent versus 67 percent) (NBS Kenya 2007) and lower HIV prevalence (5.6 percent versus 3.8 percent) (NASCOP 2007).

Integra originally sought a controlled pre/post‐test (quasi‐experimental) design to measure the effect of integrated health care in intervention sites. Due to challenges in ensuring program implementation in intervention sites, and the existence of non‐Integra integration activities in “control” sites, the latter are referred to as “comparison sites,” and in this article we treat the whole sample as a cohort to assess the effect of individuals’ exposure to integrated care on HIV testing outcomes. The cohort was female FP clients (aged 15–49 years) attending the six intervention and six comparison facilities. The facilities included six hospitals and six health centers. Characteristics of study facilities are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study facilities (pre‐intervention), by design group

| Design group | Facility codea | Type of facility | Location | Catchment population | Total FP clients (2009) | Number of nurse/ midwives in MCHb | Integration structure in 2009 (pre‐intervention)d | Pair match facility code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 23 | District hospital | Urban (city) | 560,230 | 7,402 | 14 | HTC in FP room | 4 |

| 3 | Provincial hospital | Urban (town) | 46,707 | 5,804 | 7 | HTC in FP room | 6 | |

| 10 | Health center | Peri‐urban (edge of town) | 69,363 | 5,723 | 6 | HTC in FP room | 9 | |

| 21 | Sub‐district hospital | Urban (town) | 46,707 | 2,871 | 1 | HTC in FP room | 25 | |

| 14 | Health center | Rural | 7,680 | 1,925 | 3 | HTC within MCH unit, sometimes in same room | 13 | |

| 2 | Health center | Rural | 23,000 | 2,245 | 0c | HTC in separate room | 5 | |

| Comparison | 4 | District hospital | Urban (town) | 53,541 | 5,257 | 8 | HTC in FP room | 23 |

| 6 | District hospital | Urban (town) | 308,000 | 4,529 | 3 | HTC in FP room | 3 | |

| 9 | District hospital | Rural | 21,525 | 2,245 | 3 | HTC within PMTCT, not in MCH unit | 10 | |

| 25 | Health center | Rural | 23,516 | 1,422 | 3 | HTC in FP room (part of PITC) initiative | 21 | |

| 13 | Health center | Rural | 29,880 | 3,541 | 6 | HTC within MCH unit | 14 | |

| 5 | Health center | Rural | 12,294 | 2,372 | 6 | HTC within MCH unit | 2 |

Code referred to in Mayhew et al. 2016.

Registered or enrolled.

Only one clinical officer reported.

Intervention facilities had previously received integration support.

FP = Family Planning. HTC = HIV testing and counseling. MCH = Maternal and Child Health. PITC = Provider‐initiated testing and counseling for HIV. PMTCT = Prevention of mother‐to‐child‐transmission of HIV.

SOURCE: Integra Periodic Activity Review 2009 (structured tool capturing data on service characteristics and staffing).

Intervention sites were selected based on good performance in a previous integration study (Liambila et al. 2009), were located in districts that were early implementers of national FP‐HIV integration policy, and had high client load (≥100/month). Comparison sites were located in districts that had not yet implemented national FP‐HIV integration policy, and were selected using a pair‐wise matching design, with matching based on client load, number of providers qualified and currently delivering FP services, and range of services available. Facilities were selected in different districts of the same province to minimize contamination.

The study intervention is described in detail elsewhere (Warren et al. 2012), but in short it was designed to add the following services into standard FP service delivery: discussion of fertility desires, condom promotion/provision, STI/HIV risk assessment, HIV status check, HTC provision, cervical cancer screening, pre‐HIV treatment services and/or referral to HIV treatment unit for HIV‐positive clients. The provision of these services was supported by training on and provision of an integrated client counseling toolkit, the “Balanced Counseling Strategy Plus” (BCS+) (Population Council 2016). In addition, intervention facilities were supported by nurse/midwife “mentors” who received training on SRH/HIV technical skills to provide mentorship and supportive supervision on integrated care to others on‐site (Ndwiga et al. 2014). The layout of some clinics was also reorganized to support integrated care provision, and essential equipment and supplies were provided to deliver integrated services.

Data Collection

FP clients were recruited between the end of 2009 and early 2010, and interviewed at four time points over two years: baseline (r0) (immediately after intervention implementation), round 1 (r1) (r0+6 months); round 2 (r2) (r0+18 months); and round 3 (r3) (r0+24 months). The recruitment interview took place at the health facility using a structured questionnaire on a personal digital assistant (PDA), and subsequent interviews were conducted either at the respondent's home or at an arranged meeting at the health facility, also using PDAs. The questionnaire was in Kiswahili and collected data on socio‐demographic characteristics, family planning practices, HIV‐related behaviors and practices, service‐use history, and perceptions of service quality. Respondents gave their informed consent before each interview.

At recruitment, clients were sampled consecutively as they exited consultations. Sample size calculations were based on having 80 percent power to detect an absolute between‐group increase from 5 percent to 10 percent in another study outcome (consistent condom use) among those using other contraceptive methods. Based on condom use estimates in a previous study (Liambila et al. 2009; Mwangi and Warren 2008) and with a significance level of 5 percent, it was estimated that 1,952 participants would be needed, assuming a 30 percent loss to follow‐up.

Study Population

Of the original recruitment sample (N=1,958), the following women were excluded sequentially from the analysis: 245 known to be HIV‐positive at recruitment, tested either before or during recruitment consultation (139 in intervention [14 percent] and 106 in comparison [11 percent]); 745 without a complete cohort data history (r0 through r3) (345 in intervention [41 percent] and 400 in comparison [46 percent]); and 86 missing complete data on all potentially confounding variables (64 in intervention [13 percent] and 22 in comparison [5 percent]), resulting in a sample size of 882 for a complete case analysis.

Measuring the Uptake of HIV Testing

At every round, respondents were asked whether they had received an HIV test—during consultation at recruitment, or since their last interview in subsequent rounds—and the date of the test. Participants who remained HIV‐negative (as self‐reported in cohort interviews) and received at least two HIV tests over the two‐year cohort period were considered to have fulfilled the outcome, “HTC goals achieved,” since annual testing is the national recommendation in Kenya (NASCOP 2010). Those who reported a positive HIV test during the study were categorized as “HTC goals achieved” if they reported at least one HIV test during the study.

Measures of RH‐HIV Integration

We investigated the impact of service integration on HTC uptake using four different measures of integrated care. The different approaches, summarized in Table 2, reflect different a priori questions and mechanisms—at both the facility and individual level—by which integration may influence client outcomes, and the fact that there are no standard definitions of integration in research or health practice.

Table 2.

Different measures used to define integrated care

| Research question | Integration exposure measure | Definition | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Does the Integra Intervention have an effect on HIV testing uptake among FP clients, compared with FP clients in facilities that did not receive the Integra intervention? | Design group | Attended intervention or comparison facility at the time of recruitment visit | 6 intervention, 6 comparison facilities |

| 2) Does the receipt of integrated RH‐HIV services during an FP visit increase annual HIV testing over the subsequent two years (regardless of study arm)? | Individual receipt of integrated services at baseline | Woman received a combination of at least one RH service (FP, MCH) and one HIV/STI service (HIV testing, HIV counseling, STI service) during her consultation at baseline | Binary measure (yes/no). HIV testing uptake measured at Rounds 1–3 only (baseline excluded) |

| 3) Does the level of integration at the facility lead to an increase in annual HIV testing among FP clients (regardless of study arm)? | Baseline facility integration index score | Score derived from Integra Functional Integration Index (IFII) to measure the extent of integration at the facility level | Low (≤1.99), medium (2.00 to 2.74), or high (≥2.75) index integration score |

| 4) Does the cumulative score for the level of integration in all facilities visited by a woman over two years influence her uptake of annual HIV testing? | Cumulative integration index score | Cumulative index exposure (additive score) to capture subsequent visits at study clinics | Grouped by tertiles of cumulative score into low, medium, and high. |

The first measure, “Design group,” categorized women by the study arm (per protocol), based on whether the facility from where they were recruited was designated as an intervention or comparison site. This maintains the original quasi‐experimental approach.

Subsequent exposures use a cohort study design. The second measure captured each individual woman's actual receipt of integrated services during the recruitment consultation, irrespective of the facility's designation as intervention or comparison site in the study. Services used were self‐reported by women in the exit interview. “Integrated services” were defined as a visit in which a woman received at least one RH service (FP counseling, FP method provision/check‐up, postnatal care for mother, postnatal care for baby, child health, or cervical cancer screening) AND at least one HIV/STI service (STI counseling or treatment, HIV counseling, HIV test, HIV treatment and care, psycho‐social support for HIV, treatment of opportunistic infections, TB service). Since HIV testing forms a part of this definition, the outcome measure for this exposure was restricted to HIV tests received in rounds 1–3 only (excluding r0).

The third measure recorded the degree of integrated care being delivered at the facility at recruitment, as measured by the Integra Functional Integration Index. The Integra Index is a multidimensional score of facility‐level integration derived from data collected through client flow analyses and calculated using latent variable modeling (Mayhew et al. 2016). The Index measures integration as a continuum, so that differences in the extent and nature of integration across facilities can be understood. It is derived from four indicators capturing the extent to which a facility's clients receive both RH and HIV services during their visits. Index scores at recruitment ranged from 0.87 to 3.42 across the 12 facilities; they were categorized into low (≤1.99), medium (2.00–2.74), or high (≥2.75) index integration scores, based on the distribution of the data.

Since women may return for FP consultations differentially, or switch facilities (i.e., visit facilities other than the recruitment facility) during the two‐year follow‐up period of the study, and the extent of integration at a facility can vary over time, the fourth measure recorded a cumulative integration score that took into account each woman's individual use of integrated clinics throughout the study (as self‐reported by women in each cohort interview). To calculate the cumulative score, Index scores were summed for every FP visit reported over the two‐year cohort period, although scores for visits to non‐Integra study facilities were not captured (14 percent and 16 percent of FP visits at r2 and r3, respectively). The cumulative exposure score was grouped into three categories—low, medium, and high—based on tertiles of the data (since scores were more evenly distributed across the far wider range of individual scores).

Statistical Analyses

Data were imported into STATA 13.0 for cleaning, checking, and analysis. We used z tests for differences in proportions in HIV testing between cohort rounds, and chi squared tests for crude associations between HIV testing and each of the four measures of integration, as well as between potentially confounding variables and outcome.

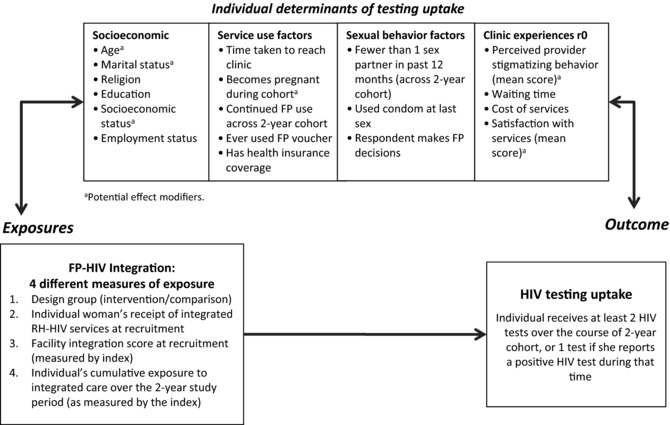

Potential confounders were identified through a review of the literature of factors influencing HIV testing uptake (Kalichman and Simbayi 2003; Zeelie, Bornman, and Botes 2003; Fylkesnes and Siziya 2004; Warwick 2006; Nakanjako et al. 2007; Musheke et al. 2013), and are displayed in the conceptual framework in Figure 1. Most of these factors were measured at r0, though selected indicators were recorded at every round (“Becomes pregnant,” “Continued use of FP,” “More than one sex partner in past 12 months [at any time]”). Socioeconomic status groupings were based on a principal components analysis of household assets. The “provider stigma score” was based on a mean score derived from Likert scales (1–5) on client reports on the following clinic characteristics: privacy, confidentiality of consultation, trust in records being kept confidential, and people living with HIV (PLHIV) treated same as others. “Satisfaction with services” was based on a mean score derived from Likert scales (1–5) on: overall service rating, costs, waiting time, availability of drugs and supplies, possibility of receiving other services at the same time, opening times, provider friendliness, doctor/nurse availability, providers listened, client could ask questions.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework identifying potential mediators of the relationships between integration and HIV testing uptake

Multivariable analyses were conducted to test the association between integration exposure and achievement of HTC goals, to control for potential confounding. We used conditional logistic regression models to account for clustering at the facility level, including all potential confounders in the model (i.e., theory‐driven selection of variables). Potential effect modification of the relationship between integration and HIV testing by certain variables (identified conceptually, see Figure 1) was tested using the Mantel‐Haenszel method, but no effect modification was found (data not shown).

Sensitivity Analyses

To examine the effect of facility pair‐matching, we also constructed a conditional regression model using the STATA svy commands to account for clustering within matched pairs, in addition to the conditional dependency on the facility cluster. Analyses that allowed for such clustering (by facility pairs) gave almost identical results to those that assumed independence, and the latter are reported.

Sensitivity analyses were also conducted for missing data on complete cases. We conducted χ2 statistical tests to assess how those with complete cohort data differed from those with an incomplete cohort history across baseline exposure and potential confounding factors. Those with complete data differed from those who were excluded from the analysis in age (p<0.001, with those in the youngest age group less likely to have complete data), and whether they paid fees for services (p=0.017, those paying fees were less likely to have complete data). There was no evidence of a difference in other baseline characteristics or between clinics. The implications of these differences are addressed in the discussion.

RESULTS

Table 3 displays the socio‐demographic and service‐related characteristics of the study population, in aggregate and by design group. Women in intervention clinics were younger (17 percent were over 35, versus 28 percent at comparison sites), had similar marital patterns (97 percent of both groups were married), had different religious beliefs (with fewer Pentecostals (32 percent versus 40 percent), were more highly educated (10 percent had received some tertiary education versus 3 percent in comparison sites), had higher self‐employment (46 percent versus 37 percent) and lower manual employment (6 percent versus 16 percent), and lived further from their clinic (45 percent lived more than 30 minutes away versus none in comparison sites). In terms of SRH behaviors, the groups had similar probabilities of becoming pregnant or continuing FP over the cohort (16 percent versus 12 percent, and 80 percent versus 83 percent, respectively); intervention participants were less likely to use a voucher for FP (3 percent versus 6 percent), but had similar health insurance (22 percent overall). Multiple sexual partnerships were commonly low across the groups (2.4 percent overall), as was condom use at last sex (3.4 percent). Women in intervention clinics were more likely to make decisions concerning FP than those in comparison clinics (57 percent versus 47 percent). They were more likely to be dissatisfied with services (10 percent versus 5 percent) and to have waited longer (57 percent had to wait more than 30 minutes, versus 0.2 percent in comparison sites), though they were less likely to have paid fees for services (83 percent versus 93 percent).

Table 3.

Socio‐demographic and health service characteristics of study sample, by design group

| Comparison | Intervention | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | P value (χ2) |

| Age group | |||||||

| Under 25 | 114 | (25.7) | 117 | (26.7) | 231 | (26.2) | <0.001 |

| 25–29 | 109 | (24.6) | 142 | (32.3) | 251 | (28.5) | |

| 30–34 | 95 | (21.4) | 107 | (24.4) | 202 | (22.9) | |

| 35–39 | 85 | (19.2) | 52 | (11.8) | 137 | (15.5) | |

| 40 and over | 40 | (9.0) | 21 | (4.8) | 61 | (6.9) | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Single or has boyfriend/partner | 8 | (1.8) | 9 | (2.1) | 17 | (1.9) | 0.904 |

| Married | 431 | (97.3) | 427 | (97.3) | 858 | (97.3) | |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 4 | (0.9) | 3 | (0.7) | 7 | (0.8) | |

| Religion | |||||||

| Protestant | 138 | (31.2) | 155 | (35.3) | 293 | (33.2) | 0.050 |

| Roman Catholic | 104 | (23.5) | 125 | (28.5) | 229 | (26.0) | |

| Pentecostal | 179 | (40.4) | 141 | (32.1) | 320 | (36.3) | |

| Other/None | 22 | (5.0) | 18 | (4.1) | 40 | (4.5) | |

| Education (highest level) | |||||||

| None/Primary | 286 | (64.6) | 236 | (53.8) | 522 | (59.2) | <0.001 |

| Secondary | 144 | (32.5) | 161 | (36.7) | 305 | (34.6) | |

| Tertiary | 13 | (2.9) | 42 | (9.6) | 55 | (6.2) | |

| Socio‐economics status score (quintiles) | |||||||

| 1st (poorest) | 117 | (26.4) | 66 | (15.0) | 183 | (20.7) | <0.001 |

| 2nd | 99 | (22.3) | 78 | (17.8) | 177 | (20.1) | |

| 3rd | 93 | (21.0) | 82 | (18.7) | 175 | (19.8) | |

| 4th | 79 | (17.8) | 93 | (21.2) | 172 | (19.5) | |

| 5th (wealthiest) | 55 | (12.4) | 120 | (27.3) | 175 | (19.8) | |

| Employment status | |||||||

| Student/Unemployed | 160 | (36.1) | 152 | (34.6) | 312 | (35.4) | <0.001 |

| Casual worker/Informal sector | 32 | (7.2) | 40 | (9.1) | 72 | (8.2) | |

| Employed (manual) | 70 | (15.8) | 24 | (5.5) | 94 | (10.7) | |

| Self‐employed | 162 | (36.6) | 201 | (45.8) | 363 | (41.2) | |

| Employed (professional/technical) | 19 | (4.3) | 22 | (5.0) | 41 | (4.6) | |

| Time to reach clinic (minutes) | |||||||

| 0–30 | 443 | (100.0) | 241 | (54.9) | 684 | (77.6) | <0.001 |

| 31–60 | 0 | (0.0) | 123 | (28.0) | 123 | (13.9) | |

| >60 | 0 | (0.0) | 75 | (17.1) | 75 | (8.5) | |

| Became pregnant during cohort | 53 | (12.0) | 68 | (15.5) | 121 | (13.7) | 0.128 |

| Continued FP through cohort | 369 | (83.3) | 350 | (79.7) | 719 | (81.5) | 0.172 |

| Used FP voucher | 28 | (6.3) | 13 | (3.0) | 41 | (4.6) | 0.018 |

| Health insurance | 89 | (20.1) | 105 | (23.9) | 194 | (22.0) | 0.170 |

| Multiple sexual partners (any cohort round) | 12 | (2.7) | 9 | (2.1) | 21 | (2.4) | 0.521 |

| Condom use at last sex | 15 | (3.4) | 15 | (3.4) | 30 | (3.4) | 0.980 |

| Who makes FP decisions? | |||||||

| Woman decides | 207 | (46.7) | 252 | (57.4) | 459 | (52.0) | 0.003 |

| Partner or provider decides | 53 | (12.0) | 32 | (7.3) | 85 | (9.6) | |

| Both agree/other | 183 | (41.3) | 155 | (35.3) | 338 | (38.3) | |

| Provider stigmatizing behavior perception (r0) | |||||||

| Low | 88 | (19.9) | 182 | (41.5) | 270 | (30.6) | <0.001 |

| Medium | 335 | (75.6) | 233 | (53.1) | 568 | (64.4) | |

| High | 20 | (4.5) | 24 | (5.5) | 44 | (5.0) | |

| Satisfaction with services (r0) | |||||||

| High | 118 | (26.6) | 131 | (29.8) | 249 | (28.2) | 0.004 |

| Medium | 304 | (68.6) | 265 | (60.4) | 569 | (64.5) | |

| Low | 21 | (4.7) | 43 | (9.8) | 64 | (7.3) | |

| Paid fees for services (r0) | 411 | (92.8) | 362 | (82.5) | 773 | (87.6) | <0.001 |

| Waiting time | |||||||

| ≤30 mins | 442 | (99.8) | 190 | (43.3) | 632 | (71.7) | <0.001 |

| >30 mins | 1 | (0.2) | 249 | (56.7) | 250 | (28.3) | |

| Total | 443 | (100.0) | 439 | (100.0) | 882 | (100.0) | |

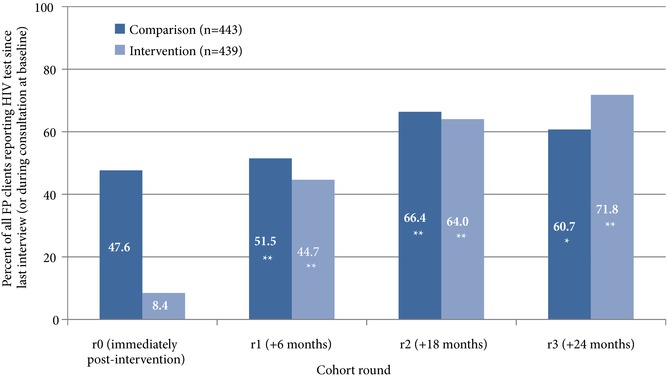

Overall, 69.3 percent of women achieved HIV testing goals over the two‐year cohort. Thirty percent received two HIV tests, 28 percent received three, and 10 percent received four (data not shown). Reports of HIV testing increased markedly over the course of the cohort, from 28 percent at baseline (during consultation) to 48 percent at r1, 65 percent at r2, and 66 percent at r3 (all reported as test since last interview) (data not shown). In the comparison facilities, an average of 48 percent of participants received an HIV test at baseline (see Figure 2). This increased slightly to 52 percent at r1 and jumped to 66 percent at r2 before a slight reduction to 61 percent in the final round. In contrast, participants in intervention facilities reported far lower levels of HIV testing at recruitment (8 percent). By r1, reports jumped significantly to 45 percent and continued to increase in r2 (to 64 percent) and in r3, when 72 percent of women recruited in intervention facilities reported receiving an HIV test since their last interview.

Figure 2.

Proportion who reported receiving an HIV test since last interview, by round and design group

Difference from previous round: **p<0.01; *p<0.05.

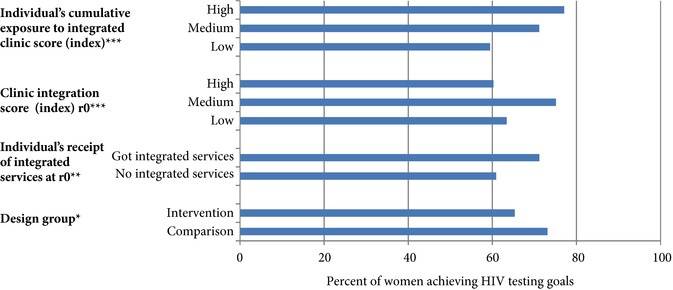

Figure 3 displays HIV testing outcomes by the four different exposure measures. Over the course of the study, more women in the comparison group (73 percent) met the HIV testing goal compared to the intervention group (65 percent). Women who received integrated services at baseline—regardless of design group—were more likely to receive the two‐test minimum (after r0) (71 percent) compared to those who did not (61 percent). There was no clear association with baseline integration index score, with those visiting a facility with a “medium” integration score most likely to receive the test outcome (75 percent) versus the high (60 percent) and the low (63 percent) groups. There was a clearer association with the cumulative integration index score, with those women having the highest cumulative exposure to integrated services most likely to have received the testing requirement (77 percent) versus the medium‐score group (71 percent) and the low‐score group (60 percent).

Figure 3.

Percent of women achieving HIV testing goals over the two‐year cohort, by different exposure groups (n=882)

Chi‐squared test: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p≤0.001.

For the two exposure measures with a crude positive impact of integration (individual's receipt of integration at baseline and cumulative clinic integration score), we further tested these associations through multivariable analyses. Association between individual receipt of integration and achievement of HTC goals became nonsignificant after adjustment (aOR 1.38, 95%CI 0.88‐2.18) (data not shown). For the cumulative clinic integration score exposure, both crude and adjusted associations between integration and HTC goals, as well as with other socio‐demographic and service‐related covariates, are presented in Table 4. After adjustment, strong evidence remained of the association between cumulative exposure to integrated clinics and HTC goal achievement: those with medium exposure to clinic integration had nearly double the odds of achieving HTC goals than those in the low‐exposure group (aOR 1.92, 95%CI 1.24‐2.97), and those in the highest exposure group had nearly three times the odds of HTC goal achievement (aOR 2.94, 95%CI 1.73‐4.98). Few other covariates were associated with testing uptake (see grey shading). There was weak evidence that women becoming pregnant subsequent to r0 had higher odds of testing uptake (aOR 1.97, 95%CI 0.95‐2.68), and those who had health insurance at r0 were also more likely to report testing uptake (aOR 1.59, 95%CI 1.05‐2.50).

Table 4.

Multivariable results of association between cumulative integration index score and HIV testing outcome (n=882)

| HIV testing | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable/category | N | N | % | cOR | 95%Cl | aORa | 95%CI |

| Cumulative exposure to integration score | |||||||

| Low | 294 | 175 | (59.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Medium | 295 | 210 | (71.2) | 1.68 | (1.19–2.37) | 1.92 | (1.24–2.97) |

| High | 293 | 226 | (77.1) | 2.29 | (1.60–3.28) | 2.94 | (1.73–4.98) |

| Age group | |||||||

| Under 25 | 231 | 169 | (73.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 25–29 | 251 | 164 | (65.3) | 0.69 | (0.47–1.02) | 0.73 | (0.47–1.12) |

| 30–34 | 202 | 138 | (68.3) | 0.79 | (0.52–1.20) | 0.88 | (0.56–1.41) |

| 35–39 | 137 | 96 | (70.1) | 0.86 | (0.54–1.37) | 0.70 | (0.41–1.21) |

| 40 and over | 61 | 44 | (72.1) | 0.95 | (0.51–1.78) | 0.65 | (0.30–1.41) |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Single or has boyfriend/partner | 17 | 15 | (88.2) | 3.39 | (0.77–14.92) | 3.30 | (0.65–16.72) |

| Married | 858 | 591 | (68.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 7 | 5 | (71.4) | 1.13 | (0.22–5.86) | 1.81 | (0.29–11.16) |

| Religion | |||||||

| Protestant | 293 | 203 | (69.3) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Roman Catholic | 229 | 163 | (71.2) | 1.09 | (0.75–1.60) | 1.21 | (0.79–1.85) |

| Pentecostal | 320 | 216 | (67.5) | 0.92 | (0.65–1.30) | 0.84 | (0.57–1.25) |

| Other/None | 40 | 29 | (72.5) | 1.17 | (0.56–2.44) | 0.99 | (0.42–2.32) |

| Education | |||||||

| None/Primary | 522 | 374 | (71.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Secondary | 305 | 203 | (66.6) | 0.79 | (0.58–1.07) | 0.80 | (0.56–1.16) |

| Tertiary | 55 | 34 | (61.8) | 0.64 | (0.36–1.14) | 0.83 | (0.40–1.74) |

| Socio‐economic status quantile | |||||||

| 1st (poorest) | 183 | 135 | (73.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2nd | 177 | 124 | (70.1) | 0.83 | (0.52–1.32) | 1.33 | (0.78–2.27) |

| 3rd | 175 | 129 | (73.7) | 1.00 | (0.62–1.60) | 1.68 | (0.95–2.99) |

| 4th | 172 | 110 | (64.0) | 0.63 | (0.40–0.99) | 1.37 | (0.76–2.45) |

| 5th (wealthiest) | 175 | 113 | (64.6) | 0.65 | (0.41–1.02) | 1.55 | (0.81–2.96) |

| Employment status | |||||||

| Student/Unemployed | 312 | 213 | (68.3) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Casual worker/Informal sector | 72 | 45 | (62.5) | 0.77 | (0.45–1.32) | 0.74 | (0.41–1.36) |

| Employed (manual) | 94 | 73 | (77.7) | 1.62 | (0.94–2.77) | 0.82 | (0.42–1.62) |

| Self‐employed | 363 | 256 | (70.5) | 1.11 | (0.80–1.54) | 0.84 | (0.56–1.25) |

| Employed (professional/technical) | 41 | 24 | (58.5) | 0.66 | (0.34–1.28) | 0.67 | (0.30–1.50) |

| Distance from clinic (minutes) | |||||||

| 0–30 | 684 | 473 | (69.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 31–60 | 123 | 77 | (62.6) | 0.75 | (0.50–1.11) | 0.96 | (0.58–1.59) |

| >60 | 75 | 61 | (81.3) | 1.94 | (1.06–3.55) | 1.33 | (0.61–2.88) |

| Became pregnant over cohort | |||||||

| No | 761 | 522 | (68.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 121 | 89 | (73.6) | 1.27 | (0.83–1.96) | 1.59 | (0.95–2.68) |

| Continued use of FP over cohort | |||||||

| No | 163 | 102 | (62.6) | 0.69 | (0.48–0.98) | 0.78 | (0.50–1.24) |

| Yes | 719 | 509 | (70.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Used FP voucher | |||||||

| No | 841 | 578 | (68.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 41 | 33 | (80.5) | 1.88 | (0.86–4.12) | 1.30 | (0.53–3.18) |

| Has health insurance | |||||||

| No | 688 | 475 | (69.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 194 | 136 | (70.1) | 1.05 | (0.74–1.49) | 1.62 | (1.05–2.50) |

| Multiple sex partners | |||||||

| No | 861 | 594 | (69.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 21 | 17 | (81.0) | 1.91 | (0.64–5.73) | 1.88 | (0.53–6.65) |

| Condom use at last sex | |||||||

| No | 852 | 590 | (69.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 30 | 21 | (70.0) | 1.04 | (0.47–2.29) | 1.58 | (0.65–3.88) |

| Who makes FP decisions | |||||||

| Woman decides | 459 | 313 | (68.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Partner/provider decides | 85 | 63 | (74.1) | 1.34 | (0.79–2.25) | 1.27 | (0.70–2.31) |

| Both agree/other | 338 | 235 | (69.5) | 1.06 | (0.79–1.44) | 1.11 | (0.78–1.57) |

| Provider stigmatizing behavior r0 | |||||||

| Low | 270 | 192 | (71.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Medium | 568 | 385 | (67.8) | 0.85 | (0.62–1.17) | 0.81 | (0.54–1.22) |

| High | 44 | 34 | (77.3) | 1.38 | (0.65–2.93) | 1.22 | (0.48–3.10) |

| Satisfaction score r0 | |||||||

| High | 249 | 175 | (70.3) | 0.66 | (0.34–1.27) | 0.94 | (0.42–2.09) |

| Medium | 569 | 386 | (67.8) | 0.59 | (0.32–1.10) | 0.87 | (0.42–1.83) |

| Low | 64 | 50 | (78.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Paid fees r0 | |||||||

| No | 109 | 82 | (75.2) | 1.40 | (0.88–2.22) | 0.92 | (0.48–1.76) |

| Yes | 773 | 529 | (68.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Waiting time r0 | |||||||

| ≤30 mins | 632 | 447 | (70.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| >30 mins | 250 | 164 | (65.6) | 0.79 | (0.58–1.08) | 1.31 | (0.82–2.08) |

Adjusted for all other variables in table.

DISCUSSION

This analysis demonstrates the complexity of assessing the effect of health service re‐organization on health and behavioral outcomes. The results show that determining whether “service integration” impacts uptake of HIV testing depends on how “integration” is measured. Findings also point to the need to articulate a precise definition of the type of integrated service‐delivery that is occurring at any given clinic if meaningful interpretation is to be achieved.

An integration intervention had a positive effect on initially increasing HIV testing uptake from very low levels immediately post‐intervention, as the proportion of FP clients at these facilities who received an HIV test increased dramatically over the course of the study, particularly in the first six months after the intervention. In contrast, the “comparison” sites provided much higher levels of HIV testing at r0, and levels rose moderately over time. The dramatic increase in HIV testing in intervention facilities replicates positive results reported in a previous uncontrolled study of a similar intervention in Central Province, Kenya (Liambila et al. 2009). The greater increase in intervention clinics relative to comparison sites suggests that the BCS+ toolkit was effective in encouraging providers to promote HIV testing, in particular where there was a low baseline and potential latent demand for testing (Population Council 2016). The BCS+ toolkit is an evidence‐based, interactive, client‐friendly approach that aims to improve contraceptive counseling by addressing a variety of topics relevant to FP including prevention, detection/testing, and treatment of HIV and STIs; postpartum maternal and newborn care; and cervical cancer screening. Other provider job aids have been found to be effective in supporting integration activities, including screening tools and flip‐charts (Kim et al. 2005; Foreit 2006; Baumgartner et al. 2014), and programs should continue to support their use to broaden the scope of health consultations. The costs of production of and training on job aids can seem prohibitive to programs, but the existence of proven global or national tools should make their adaptation, implementation and/or dissemination easier. In Kenya, Integra was able to review and update existing MOH job aids. Another report from Integra has also pointed to the important role mentors played during the intervention, helping to improve provider knowledge, skills, self‐confidence, and teamwork (Ndwiga et al. 2014).

We found no difference, however, between attendance at intervention clinics and achievement of total testing goals over the two‐year study period, likely due to markedly lower r0 levels of testing in intervention sites. One explanation for lower levels of HIV testing at intervention sites at r0 may have been previous receipt of HIV testing, potentially resulting from the previous integration support (Liambila et al. 2009). This is compounded by the fact that prior to 2010 retesting guidance was unclear, and annual testing was not made explicit. Since our questionnaire only recorded past testing history among those who received an r0 test, it is not possible to contrast or control for baseline differences; but among those whose history was recorded, testing levels were indeed far higher in intervention than control sites (89.8 percent versus 50.8 percent). In addition, adhoc program changes may have blurred the categorization by design groups: in intervention sites there were challenges with test‐kit stock‐outs and in‐staff rotation, limiting intervention activities, and in comparison sites initiatives from the Ministry of Health and partner agencies were encouraging HTC for the three months around recruitment. Another Integra analysis, developing the Integra Indexes, demonstrated that integration scores (i.e., the provision of multiple services by one provider, within one consultation or within one visit) did not correlate with design group and thus the relatively large observed increase in testing uptake at intervention sites after r0 should be interpreted with caution (Mayhew et al. 2016). This and other Integra analysis indicated that health‐facility structures need to be prepared with equipment and training before integration activities can occur, but these structural inputs are not in themselves sufficient to achieve integrated service delivery—which will depend on staff action, motivation, and support (Mayhew et al. 2016; Mayhew et al., forthcoming).

To answer the question of whether “integrated services” have an effect on testing goals, it has been informative to also investigate the impact of integration measured in other ways. We found a crude effect on HTC uptake of an individual's receipt of integrated RH‐HIV services at baseline, but not after adjustment. An individual's cumulative exposure to integrated clinics over time, as measured by the multidimensional index of integration was, however, still significantly associated with testing uptake after adjustment for confounding. This implies that women who return frequently for FP services to more integrated clinics are more likely to receive their recommended HIV tests than women who return frequently to less integrated clinics. Family planning services often require follow‐up visits, but efforts may be required to encourage women to return who have either discontinued or opted for long‐term reversible or permanent contraceptive methods. Follow‐up visits would have the beneficial impact of encouraging engagement with both the FP and HIV service components.

It was also surprising that so few other socio‐demographic or behavioral factors were associated with testing uptake. Women who became pregnant were more likely to get tested, reflecting the provision of HTC in antenatal care. Interestingly, having health insurance was associated with testing goals, which is surprising given the supposedly free provision of HTC and ART in Kenya. Insurance may be promoting the use of other services, however, which then provide the opportunity for testing promotion. Other factors that might have been expected to influence HTC, such as perceived provider stigma, distance living from a testing site, socio‐economic status, and age (Obermeyer and Osborn 2007; Musheke et al. 2013), all had no influence. The fact that this analysis investigated the receipt of at least two tests over a two‐year period may explain this difference, since existing studies have focused on uptake of a first HIV test. Repeat testing is therefore seemingly more heavily influenced by clinic‐level factors, and this analysis shows that repeated integration exposure is one of them. This therefore provides a strong rationale for national health programs to respond by scaling up the integration of HIV testing into FP services.

In addition to problems associated with categorization by design group noted above, this analysis has other important limitations. First, the quasi‐experimental design implies risk of selection bias. Unmeasured confounding from other factors affecting testing uptake is plausible, and in particular the failure to control to past testing history, as noted above, may have influenced findings. Other factors that we could not control for, but which have been shown to influence testing uptake include perceived availability of ART at the clinic, perceived risk of HIV infection, physical health symptoms, and death of a sexual partner and/or child (Musheke et al. 2013). Nevertheless, most of these other factors would not be expected to vary by clinic. Perceived availability of ART is implicitly linked to clinic integration score, and therefore could not be included independently. There is also possible selection bias in our results due to incomplete cases and loss to follow‐up. Complete cohort cases differed from those lost to follow‐up across several important variables. Those with incomplete data were younger and more likely to have paid fees for services; the former could have resulted in underestimates of testing uptake. Since they did not differ by clinic, however, this bias should not have heavily influenced effect estimates reported here.

Second, the calculation of the cumulative facility index score has limitations. We were unable to calculate scores for visits to non‐Integra study facilities, and there were inconsistencies in recording of intervening facility visits between cohort rounds. At r1, information was captured on up to five intervening consultations, whereas information at r2 and r3 was restricted to the last visit. The effect of clinic exposure over time may therefore be underestimated in sites that would be more likely to encourage clients to come back more often.

Last, while efforts were made to remove duplicate reporting of HIV testing, our data cleaning indicated that respondents struggled to recall or report accurate HIV testing dates. Despite efforts to remove duplicate reports (e.g., where reported dates were very similar), there was still the possibility that tests reported in later rounds were duplications of tests reported earlier. Additionally, reporting bias may have increased over time with repeated survey rounds, thus potentially contributing to the markedly higher rates of testing over the course of the cohort. Reporting bias should not have differed between exposures, however.

CONCLUSION

Assessing the impact of organizational changes on service outcomes is complex and sensitive to measurement definition choices. Using a range of measurements, our findings show that integrated delivery affects HIV testing goals if repeated contact with the integrated‐care delivery is sustained over time. Strategies to integrate HIV testing into FP services must therefore address sustained integrated delivery and encouragement of repeat service use by clients to ensure that they achieve their routine testing goals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Integra Initiative is a research collaboration between the International Planned Parenthood Federation, the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, and the Population Council, investigating the benefits and costs of integrated SRH and HIV services and is supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Integra Initiative research was conducted in Swaziland, Kenya and Malawi. The research team includes the authors of this article plus: Ian Askew, Manuela Colombini, Natalie Friend du‐Preez, Joshua Kikuvi, Jackline Kivunaga, Joelle Mak, Christine Michaels, Richard Mutemwa, Carol Dayo Obure, Anna Vassall, and Charlotte Watts.

Kathryn Church, Isolde Birdthistle, and Keith Tomlin are Assistant Professors, Department of Population Health, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Keppel St., London, WC1E 7HT, UK. Email: kathryn.church@lshtm.ac.uk. Charlotte E. Warren is Senior Associate, Population Council, Washington, DC. George B. Ploubidis is Professor, Centre for Longitudinal Studies, Department of Social Science, University College London, UK. Sedona Sweeney is Research Fellow and Susannah H. Mayhew is Professor, Department of Global Health and Development, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK. Weiwei Zhou is a PhD student, University of Oxford, UK. James Kimani and Charity Ndwiga are Program Officers, and Timothy Abuya is Associate, Population Council, Nairobi.

Footnotes

The Integra Initiative is a registered clinical trial (No. NCT01694862) at clinicaltrials.gov.

REFERENCES

- Askew, Ian and Berer Marge. 2003. “The contribution of sexual and reproductive health services to the fight against HIV/AIDS: A review,” Reproductive Health Matters 11(22): 51–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggaley, R. et al. 2012. “From caution to urgency: The evolution of HIV testing and counselling in Africa,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 90(9): 652–658B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, J.N. et al. 2014. “Integrating family planning services into HIV care and treatment clinics in Tanzania: Evaluation of a facilitated referral model,” Health Policy and Planning 29(5): 570–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, H. et al. 2008. “HIV and family planning service integration and voluntary HIV counselling and testing client composition in Ethiopia,” AIDS Care 20(1): 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison, Julie A. et al. 2008. “HIV voluntary counseling and testing and behavioral risk reduction in developing countries: A meta‐analysis, 1990–2005,” AIDS and Behavior 12(3): 363–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, Lilian and Garner Paul. 2011. “Strategies for integrating primary health services in low‐ and middle‐income countries at the point of delivery.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreit, J. 2006. “Systematic screening: A strategy for determining and meeting clients’ reproductive health needs.” Washington, DC: Population Council. [Google Scholar]

- Fylkesnes, Knut and Siziya Seter. 2004. “A randomized trial on acceptability of voluntary HIV counselling and testing,” Tropical Medicine and International Health 9(5): 566–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlihy, Julie et al. 2015. “Implementation and operational research: Integration of PMTCT and antenatal services improves combination antiretroviral therapy uptake for HIV‐positive pregnant women in southern Zambia: A prototype for Option B+?” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 70(4): e123–e129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman, S.C. and Simbayi L.C.. 2003. “HIV testing attitudes, AIDS stigma, and voluntary HIV counselling and testing in a black township in Cape Town, South Africa,” Sexually Transmitted Infections 79(6): 442–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, Caitlin E. et al. 2010. “Linking sexual and reproductive health and HIV interventions: A systematic review,” Journal of the International AIDS Society 13: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, Caitlin E. et al. 2013. “Provider‐initiated HIV testing and counseling in low‐ and middle‐income countries: A systematic review,” AIDS and Behavior 17(5): 1571–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Young Mi et al. 2005. “Promoting informed choice: Evaluating a decision‐making tool for family planning clients and providers in Mexico,” International Family Planning Perspectives 31(4): 162–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon, Natalie et al. 2010. “The impact of provider‐initiated (opt‐out) HIV testing and counseling of patients with sexually transmitted infection in Cape Town, South Africa: A controlled trial,” Implementation Science 5: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liambila, W. et al. 2009. “Feasibility and effectiveness of integrating provider‐initiated testing and counselling within family planning services in Kenya,” AIDS 23: S115–S121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindegren, M.L. et al. 2012. “Integration of HIV/AIDS services with maternal, neonatal and child health, nutrition, and family planning services.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 9: CD010119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew, Susannah H. et al. 2016. “Innovation in evaluating the impact of integrated service‐delivery: The Integra Indexes of HIV and reproductive health integration,” PLoS One 11(1): e0146694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew, S.H . et al. Forthcoming. “Numbers, systems, people—how interactions influence integration: Insights from case studies of HIV and reproductive health services delivery in Kenya,” Health Policy and Planning. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOPHS . 2009. “National reproductive health and HIV and AIDS integration strategy.” Nairobi: Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation and Ministry of Medical Services. [Google Scholar]

- MOPHS . 2012. “Minimum package for reproductive health and HIV integrated services.” Nairobi: Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation and Ministry of Medical Services. [Google Scholar]

- Musheke, Maurice et al. 2013. “A systematic review of qualitative findings on factors enabling and deterring uptake of HIV testing in Sub‐Saharan Africa,” BMC Public Health 13: 220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwangi, Annie and Warren Charlotte. 2008. “Strengthening postnatal care services including postpartum family planning in Kenya.” Frontiers in Reproductive Health, Population Council. [Google Scholar]

- Nakanjako, Damalie et al. 2007. “Acceptance of routine testing for HIV among adult patients at the medical emergency unit at a national referral hospital in Kampala, Uganda,” AIDS and Behavior 11(5): 753–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NASCOP . 2007. Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2007: Final Report. Nairobi: National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP). [Google Scholar]

- NASCOP . 2010. “Repeat and Re‐Testing Guidance.” Nairobi. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics Kenya (NBS Kenya) . 2007. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2007. Calverton, MD: ICF International. [Google Scholar]

- Ndwiga, Charity et al. 2014. “Exploring experiences in peer mentoring as a strategy for capacity building in sexual reproductive health and HIV service integration in Kenya,” BMC Health Services Research 14: 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermeyer, Carla M . and Osborn Michelle O.. 2007. “The utilization of testing and counseling for HIV: A review of the social and behavioral evidence,” American Journal of Public Health 97(10): 1762–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope, Diane S. et al. 2008. “A cluster‐randomized trial of provider‐initiated (opt‐out) HIV counseling and testing of tuberculosis patients in South Africa,” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 48(2): 190–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Population Council . 2016. “The Balanced Counseling Strategy Plus: A Toolkit for Family Planning Service Providers Working in High HIV/STI Prevalence Settings (Third Edition).” New York. [Google Scholar]

- Roura, Maria et al. 2013. “Provider‐initiated testing and counselling programmes in sub‐Saharan Africa: A systematic review of their operational implementation,” AIDS 27(4): 617–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibide, Michel and Buse Kent. 2009. “Strength in unity,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 87(11): 806–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staveteig, Sarah et al. 2013. “Demographic Patterns of HIV Testing Uptake in Sub‐Saharan Africa: DHS Comparative Reports No. 30.” Calverton, MD: ICF International. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS . 2013. “UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2013.” Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS . 2014a. “90‐90‐90: An Ambitious Treatment Target to Help End the AIDS Epidemic.” Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS . 2014b. “The Gap Report.” Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, Charlotte E. et al. 2012. “Study protocol for the Integra Initiative to assess the benefits and costs of integrating sexual and reproductive health and HIV services in Kenya and Swaziland,” BMC Public Health 12: 973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warwick, Zoe 2006. “The influence of antiretroviral therapy on the uptake of HIV testing in Tutume, Botswana,” International Journal of STD & AIDS 17(7): 479–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcher, Rose et al. 2013. “Integration of family planning into HIV services: A synthesis of recent evidence,” AIDS 27(Suppl. 1): S65–S75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeelie, S.C. , Bornman J.E., and Botes A.C.. 2003. “Standards to assure quality in nursing research,” Curationis 26(3): 4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]