Abstract

Background

Men who have sex with men (MSM) are disproportionately infected with HIV in Thailand. Factors affecting their intention to take non-occupational HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (nPEP) are not well understood. This study sought to determine factors associated with an intention to take nPEP in this population.

Method

This is a two-phase mixed-method study. Phase I was a cross-sectional survey of intention to take nPEP in 450 MSM attending for HIV testing, using a self-administered questionnaire. Phase II was a prospective descriptive study, using an in-depth interview among 40 MSM who had been exposed to HIV in the past 72 hours. Multiple logistic regression was used to evaluate factors relating to the intention to use nPEP.

Results

Among 450 MSM seeking HIV testing in Bangkok, 7% had ever taken nPEP. Only 40% expressed an intention to take it to prevent HIV acquisition, despite the fact that they were at high risk as evidenced by an 18.9% prevalence of HIV-positive status. Factors associated with an intention to take nPEP were awareness about nPEP, HIV knowledge, mode of sexual intercourse and circumcision. Among 40 MSM who were eligible for and offered nPEP, 39 agreed to take it, and all but one completed the 4-week course. Condom use increased and all 32 individuals who could be contacted tested HIV negative after nPEP.

Conclusion

A high HIV prevalence was found in MSM testing for HIV in this study. However, fewer than half of the participants expressed the intention to take nPEP if they were at risk for HIV infection. Efforts to create nPEP awareness and improve HIV knowledge in MSM are crucial to the successful implementation of nPEP as part of a combination package for HIV prevention in this high-risk population.

Keywords: nPEP, MSM, HIV infection, willingness, intention

Background

Over the past three decades, HIV/AIDS has had a profound and catastrophic impact on health and social infrastructure in diverse countries and communities. There are currently nearly 37 million people living with HIV worldwide [1]. Higher rates of infection are observed among men who have sex with men (MSM) in a number of countries, including Thailand [2–4]. HIV prevalence among MSM at the Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre (TRC-ARC), the country's largest HIV testing centre, which provides services to over 9000 MSM each year [5], was found to be 25% [6], while 80% of acute HIV infection diagnoses made at TRC-ARC were among MSM [7]. Half of MSM surveyed in Bangkok reported consistent condom use and 70% had multiple sexual partners [8], highlighting the need for combination preventive strategy. Data from animal models, perinatal clinical trials, studies of occupational exposures, and observational studies indicate that post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), when initiated within 72 hours and taken for 28 days, might reduce the risk for HIV infection after non-occupational exposure. The selection of the drug regimen depends on the source's resistance pattern, antiretroviral medication (ARV), HIV RNA level, and route and duration of exposure [9,10]. PEP is recommended for occupational and non-occupational (nPEP) HIV exposure in various settings [10,11]. In Thailand, PEP is available free of charge through the public health system only for occupational exposure. Concerns about risk disinhibition and poor adherence leading to antiretroviral resistance may contribute to the apprehension in adopting nPEP guidelines in a clinical setting [12].

Objectives

We initiated this study in order to explore the acceptance, understanding and adherence of nPEP in MSM who present at the largest HIV testing site in Bangkok, Thailand.

Materials and methods

Study design

This is a two-phase mixed-method study ( ClinicalTrials.gov; NCT02107911). Subjects enrolled were Thai MSM aged ≥18 years seeking voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) for HIV at the TRC-ARC. Individuals who were HIV positive, already taking nPEP or with other significant medical or psychological illnesses were excluded. Written informed consent was obtained. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Phase I of the study consisted of a cross-sectional quantitative survey of intention to take nPEP in 450 MSM, using a self-administered questionnaire before the counselling process. Intention to take nPEP is a commitment to use ARV for HIV prevention following risk exposure even though obstacles or difficulties may exist. Therefore, an agreement with all of the following seven points was used to define the intention to take nPEP in this study: (1) taking nPEP can prevent HIV infection; (2) nPEP should be available at any time; (3) to prevent HIV infection acquisition, nPEP is another option to choose; (4) ARVs are effective in HIV prevention; (5) trust in the healthcare provider to dispense nPEP; (6) confidence in the service standards of the clinic; and (7) ability to take ARVs regularly. Participants were asked to complete two questionnaires that enquired about demographic information, attitudes toward nPEP, substance use, sexual risk behaviours, male circumcision, and HIV and nPEP knowledge (Appendix 1). The questionnaires were modified from questionnaires previously used in the related literature and reviewed by three experts to assure their validity

Phase II of the study consisted of in-depth interviews, lasting approximately 1 hour each, of 40 MSM eligible for nPEP (11 recruited from Phase I and 29 newly recruited in Phase II). These men were either attending for HIV testing and were picked up as eligible for nPEP by physicians/experienced counsellors, or had acknowledged they were at risk and were attending requesting nPEP. Eligibility was assessed and confirmed by physicians/experienced counsellors based on a history of risk in the preceding 72 hours. The nPEP regimen offered consisted of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors plus a protease inhibitor or a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor. All participants repeated HIV testing at 6 weeks after nPEP initiation. A set of questions prior to taking nPEP was used to explore factors associated with the decision to take nPEP, condom use, sexual practices, knowledge and attitude about other HIV prevention methods. Six weeks after nPEP initiation, individuals were interviewed about their nPEP experience, sexual behaviour, attitude toward nPEP and knowledge of HIV prevention.

Laboratory diagnosis of HIV infection

The HIV testing algorithm used a fourth-generation antigen–antibody immunoassay (IA) (HIV1/2 Combo Architect, Abbott, USA) followed by a third-generation IA (Alere Determine HIV-1/2, Abbott, USA) and particle agglutination test (Serodia-HIV1/2, Fugirebio, Japan). All non-reactive fourth-generation IA samples were tested for HIV nucleic acid (APTIMA HIV-1 RNA Qualitative Assay, Hologic Inc, California, USA) with a 24-hour turnaround time.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for demographic data and Chi-squared or Fisher's exact test to examine correlations between the intention to take nPEP and categorical data. Logistic regression was used to evaluate factors relating to the intention to use nPEP. Variables with P-value <0.25 [13] were selected for multivariate analysis. Results were described as odds ratio, adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals (CI). STATA/IC version 12 for Windows (StataCorp LP, TX, USA) was used for all analyses. To analyse qualitative data, themes and sub-themes were formulated using content analysis [14].

Results

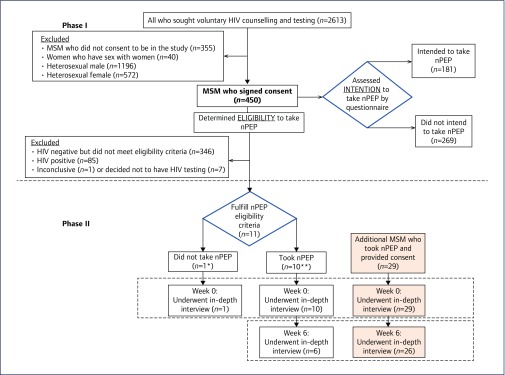

Among 2613 clients seeking VCT during March–May 2014, 805 MSM were identified; 450 (56%) were enrolled into the study while the remaining 355 did not take part due to time constraints. There were 181 (40.2%) individuals who expressed the intention to initiate nPEP at some time in the future if at risk, while 269 (59.8%) had no intention to do so. Of these 450 individuals, 11 fulfilled the nPEP eligibility criteria and participated in the study Phase II. In addition, 29 MSM eligible for nPEP were subsequently enrolled into this phase of the study. At week 6, after initiating nPEP, 32 individuals were available for interviews (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing subject participation in the study. * This participant did not show an intention to take nPEP as assessed by a questionnaire. ** Six showed an intention to take nPEP and four showed no intention to take nPEP when assessed by a questionnaire

Phase I

Characteristics of MSM (Table 1)

Table 1.

Characteristics of MSM by intention to initiate nPEP

| Characteristics | Did not intend to initiate nPEP | Intended to initiate nPEP | Total | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=269 | n=181 | n=450 | ||

| Age(years), mean(SD) | 26.9(6.1) | 26.5(6.2) | 26.8(6.1) | 0.33 |

| Highest level of education, n(%) | ||||

| Lower than high school | 14(5.2) | 3(1.7) | 17(3.8) | 0.21 |

| High school/basic technical school | 60(22.3) | 46(25.4) | 106(23.6) | |

| Advanced technical school/associate degree | 16(6.0) | 8(4.4) | 24(5.3) | |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 176(66.5) | 124(68.5) | 303(67.3) | |

| Current occupation, n(%) | ||||

| Not working/student | 99(36.9) | 78(43.3) | 177(39.5) | 0.42 |

| Company or government employee | 126(47.0) | 83(46.1) | 209(46.7) | |

| Private business/merchant | 34(12.7) | 16(8.9) | 50(11.2) | |

| Other | 9(3.4) | 3(1.7) | 12(2.7) | |

| No data | 1(0.4) | 1(0.6) | 2(0.4) | |

| Income(USD/month), median(IQR),(min–max) | 428.6(257.1–742.9), (0–600,000) | 428.6(257.1–628.6), (0–120,000) | 428.6(257.1–714.3), (0–600,000) | 0.73 |

| Prior awareness of nPEP, n(%) | 150(55.8) | 121(66.9) | 271(60.2) | 0.02 |

| Prior experience of nPEP, n(%) | ||||

| No | 254(94.4) | 163(90.1) | 417(92.1) | 0.04 |

| Not sure | 2(0.7) | 0 | 2(0.4) | |

| Yes | 12(4.5) | 18(9.9) | 30(6.9) | |

| • No side effects | 0 | 1(5.6) | 1(3.2) | |

| • Gastrointestinal discomfort | 10(76.9) | 13(72.2) | 23(74.2) | |

| • Headache/dizziness | 11(84.6) | 18(100.0) | 29(93.6) | |

| • Rash | 3(23.1) | 0 | 3(9.7) | |

| • Hepatitis | 1(7.7) | 1(5.6) | 2(6.5) | |

| • Others | 4(30.8) | 1(5.6) | 5(16.1) | |

| Reason not to take nPEP in the past(n=414), n(%) | ||||

| • No risk | 130(51.6) | 87(53.7) | 217(52.4) | 0.88 |

| • Risk exceeding 72 hours | 102(40.5) | 60(37.0) | 162(39.1) | |

| • Risk within 72 hours but was not advised by counsellor to take nPEP | 19(7.5) | 14(8.6) | 33(8.0) | |

| • Personal reasons | 1(0.4) | 1(0.6) | 2(0.5) | |

| HIV status at screening visit, n(%) | ||||

| Inconclusive | 0 | 1(0.56) | 1(0.2) | 0.71 |

| Negative | 212(78.8) | 145(80.1) | 357(79.3) | |

| Positive | 53(19.7) | 32(17.7) | 85(18.9) | |

| Decided not to test | 4(1.5) | 3(1.7) | 7(1.6) | |

nPEP: non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis; USD=US dollar

The average age of participants was 26.8 years, 67.3% had a bachelor's degree or higher education, and two-thirds were either employed or students. Sixty percent had heard about nPEP but only 7% had ever taken it. MSM who had previously taken nPEP were more likely to report having experienced neurological (93.6%) or gastrointestinal tract symptoms (74.2%) while taking it.

Eighty-five (18.9%) individuals tested positive for HIV infection and were referred for treatment, while one (0.2%) subject had inconclusive testing results. Seven (1.6%) MSM declined HIV testing after their pre-test counselling. The remaining 357 (79.3%) individuals were found to be HIV negative.

Sexual behaviour and intention to initiate nPEP

The average age of first sexual intercourse was 18 years in both groups (Table 2). In the past 3 months, 237 (52.7%) reported multiple sexual partners. Subjects without an intention to take nPEP were more likely to report insertive anal sex (60% vs 50%, P=0.04), and no differences were seen in other routes of sexual intercourse between groups. Consistent condom use was reported to be 45% with regular partners, 55% with casual partners, and 56% with commercial sex workers. Only 41% of individuals reported consistent condom use regardless of the type of sexual partners. The rate of consistent condom use tended to be higher among MSM with an intention than those without an intention to take nPEP (46% vs 37%, P=0.07).

Table 2.

Sexual risk behaviours among MSM with and without an intention to take nPEP

| Sexual behaviour | Did not intend to initiate nPEP | Intended to initiate nPEP | Total | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total=269 | Total=181 | Total=450 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age at first sexual intercourse, mean (SD) | 18.4(3.1) | 18.4(3.5) | 18.4(3.3) | 0.87 |

| Multiple partner | 141(52.4) | 96(53.0) | 237(52.7) | 0.90 |

| Routes of sexual intercourse during past 3 months | ||||

| Anal receptive | 132(49.1) | 92(50.8) | 224(49.8) | 0.72 |

| Anal insertive | 163(60.6) | 92(50.9) | 255(56.7) | 0.04 |

| Vaginal insertive | 16(6.0) | 8(4.4) | 24(5.3) | 0.48 |

| Oral receptive | 119(44.2) | 89(49.2) | 208(46.2) | 0.30 |

| Oral insertive | 137(50.9) | 91(50.3) | 228(50.7) | 0.89 |

| None of the above | 1(0.4) | 4(2.2) | 5(1.1) | 0.16 |

| Condom use with primary sexual partner in the past 3 months(n=296) | ||||

| Never | 40(22.0) | 21(18.4) | 61(20.6) | 0.08 |

| Sometimes | 68(37.4) | 30(26.3) | 98(33.1) | |

| Every time | 72(39.5) | 61(53.5) | 133(44.9) | |

| Decline to answer | 2(1.1) | 2(1.8) | 4(1.4) | |

| Condom use with casual sexual partner(s) in the past 3 months(n=303) | ||||

| Never | 24(13.0) | 15(12.6) | 39(12.9) | 0.98 |

| Sometimes | 57(31.0) | 38(31.9) | 95(31.3) | |

| Every time | 101(54.9) | 64(53.8) | 165(54.5) | |

| Decline to answer | 2(1.1) | 2(1.7) | 4(1.3) | |

| Condom use with commercial sex workers in the past 3 months(n=45) | ||||

| Never | 2(7.4) | 3(16.7) | 5(11.1) | 0.71 |

| Sometimes | 4(14.8) | 3(16.7) | 7(15.6) | |

| Every time | 15(55.6) | 10(55.6) | 25(55.6) | |

| Decline to answer | 6(22.2) | 2(11.1) | 8(17.8) | |

| Condom use with partners who provide money or goods in the past 3 months(n=29) | ||||

| Never | 4(23.5) | 4(33.3) | 8(27.6) | 0.83 |

| Sometimes | 4(23.5) | 1(8.3) | 5(17.2) | |

| Every time | 6(35.3) | 5(41.7) | 11(38.0) | |

| Decline to answer | 3(17.7) | 2(16.7) | 5(17.2) | |

| Condom use with sexual partners who use intravenous drugs in the past 3 months(n=58) | ||||

| Never | 6(18.2) | 4(16.0) | 10(17.2) | 0.30 |

| Sometimes | 3(9.1) | 0 | 3(5.2) | |

| Every time | 4(12.1) | 3(12.0) | 7(12.1) | |

| Declined to answer | 5(15.1) | 1(4.0) | 6(10.3) | |

| Don't know if my partner is an illicit intravenous drug user | 15(45.5) | 17(68) | 32(55.2) | |

| Consistent condom use for every route of sexual intercourse(n=399) | 89(36.9) | 73(46.2) | 162(40.6) | 0.07 |

| Alcohol use before or during sexual intercourse in the past 3 months(n=408) | ||||

| Never | 160(65.0) | 118(72.8) | 278(68.1) | 0.37 |

| Sometimes | 79(32.1) | 40(24.7) | 119(29.2) | |

| Every time | 4(1.6) | 3(1.9) | 7(1.7) | |

| Decline to answer | 3(1.2) | 1(0.6) | 4(1.0) | |

| Use of recreational drugs before or during sexual intercourse in the past 3 months(n=449) | ||||

| No | 227(84.6) | 155(85.6) | 382(85.1) | 0.90 |

| Yes | 40(15.0) | 25(13.8) | 65(14.5) | |

| • Methamphetamine/amphetamine | 12(30.0) | 5(20.0) | 17(26.2) | |

| • Ecstasy | 1(2.5) | 0 | 1(1.5) | |

| • Poppers | 30(75.0) | 20(80.0) | 50(76.9) | |

| • Unknown drug | 8(20.0) | 4(16.0) | 12(18.5) | |

| Decline to answer | 1(0.4) | 1(0.6) | 2(0.4) | |

| Shared intravenous needle use in the past 3 months(n=447) | ||||

| No lifetime use of recreational intravenous drugs | 263(98.6) | 178(99.8) | 441(98.7) | 0.62 |

| Prior use of recreational intravenous drugs, but not in the past 3 months | 2(0.7) | 0 | 2(0.4) | |

| Prior use of recreational intravenous drugs, but no shared needle use | 0 | 1(0.6) | 1(0.2) | |

| Prior use of recreational intravenous drugs with shared needle use | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Decline to answer | 2(0.7) | 1(0.6) | 3(0.7) | |

| Have you been circumcised?(n=450) | ||||

| Yes | 24(8.9) | 35(19.3) | 59(13.1) | 0.001 |

| • age ≥15 years old | 5(20.8) | 5(14.3) | 10(16.9)] | |

| No | 241(89.6) | 146(80.7) | 387(86.0) | |

| Decline to answer | 4(1.5) | 0 | 4(0.9) | |

nPEP: non-occupational? post-exposure prophylaxis; MSM: men who have sex with men

Use of alcohol before or during sex in the past 3 months was reported by 31% of participants. Fourteen percent reported illicit drug use, 26% of whom with amphetamine-type stimulants. The individuals who intended to take nPEP were more likely to be circumcised than those without an intention to take it (19% vs 9%, P=0.001).

Attitude toward nPEP in MSM

One-in-five participants reported that they had known someone who had taken nPEP. Ninety-two percent stated that they would seek nPEP if they had had a risk for HIV acquisition. A higher proportion of those who intended to take nPEP answered yes when asked if nPEP would reduce their concerns about becoming infected with HIV (86% vs 65%, P<0.001). There was no difference about a sense of stigmatisation between those who did and those who did not intend to take nPEP (58% vs 42%, P=0.49) (Appendix 2).

Evaluation of HIV/AIDS and nPEP knowledge (Table 3)

Table 3.

HIV/AIDS and nPEP knowledge among MSM with and without an intention to take nPEP

| Statements | Did not intend to initiate nPEP | Intended to initiate nPEP | Total | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total=269 | Total=181 | Total=450 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Correct responses to general questions about HIV/AIDS transmission | ||||

| Can you get HIV by having sexual intercourse with an infected person? | 242(90.0) | 163(90.1) | 405(90.0) | |

| Can HIV be transmitted from mother to child? | 236(87.7) | 166(91.7) | 402(89.3) | |

| Is HIV curable if diagnosed in early stage? | 93(34.6) | 69(38.1) | 162(36.0) | |

| Can you get HIV by sharing a bathroom, toilet, clothes or by kissing an infected person? | 217(80.7) | 154(85.1) | 371(82.4) | |

| Can HIV be spread via mosquito or insect bites? | 221(82.2) | 163(90.1) | 384(85.3) | |

| Can you get HIV via blood transfusion or from receiving other blood products that are infected with HIV? | 255(94.8) | 177(97.8) | 432(96.0) | |

| Can you get HIV by sharing needles with an infected person? | 263(97.8) | 179(98.9) | 442(98.2) | |

| Can you get HIV by touching or eating with an infected person? | 233(86.6) | 164(90.6) | 397(88.2) | |

| Correct responses to questions about HIV prevention | ||||

| Can you get HIV by having sexual intercourse without using a condom with a person who you know very well? | 218(81.0) | 164(90.6) | 382(84.9) | |

| Can you prevent HIV infection by always using a condom during sexual intercourse? | 198(73.6) | 159(87.8) | 357(79.3) | |

| Does ejaculating outside prevent HIV infection? | 178(66.2) | 131(72.4) | 309(68.7) | |

| Can you prevent HIV infection by avoiding sexual intercourse with sex workers? | 208(77.3) | 144(79.6) | 352(78.2) | |

| Can you prevent HIV infection by choosing to have sexual intercourse with only persons who look healthy? | 201(74.7) | 160(88.4) | 361(80.2) | |

| Can you prevent HIV infection by avoiding sexual intercourse? | 47(17.5) | 24(13.3) | 71(15.8) | |

| Can you prevent HIV infection by washing your genitals after having sexual intercourse every time? | 170(63.2) | 120(66.3) | 290(64.4) | |

| Does having an STI in combination with risky sexual behaviour with an infected person increase your chance of HIV infection? | 241(89.6) | 171(94.5) | 412(91.6) | |

| Accuracy of responses | ||||

| >80% | 130(48.3) | 115(63.5) | 245(54.4) | 0.003 |

| 50–79% | 128(47.6) | 64(35.4) | 192(42.7) | |

| <49% | 11(4.1) | 2(1.1) | 13(2.9) | |

| Correct responses to general questions about nPEP | ||||

| Where can you buy antiretroviral medication? | 241(90.1) | 170(93.9) | 411(91.5) | |

| Taking nPEP may prevent HIV infection, but within how many hours of the risk of exposure must it be taken? | 232(86.6) | 166(91.7) | 398(88.6) | |

| How should nPEP be taken? | 108(40.3) | 83(45.9) | 191(42.5) | |

| Can antiretroviral medication cause side effects in people who take it? | 154(57.7) | 124(68.9) | 278(62.2) | |

| Adequate nPEP knowledge (correctly answering ≥75% while knowing that nPEP needs to be started within 72 hours) | 158(58.7) | 124(68.5) | 282(62.7) | 0.04 |

nPEP: non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis; STI: sexually transmitted infection

More participants who intended to take nPEP had an accurate knowledge (≥80% of correct answers) about HIV transmission and prevention than those who did not (P=0.003). The majority (62.7%) had an adequate knowledge about nPEP (P=0.04). Approximately 90% knew where to buy it and how soon after HIV exposure it should be taken; however, only 43% knew that it should be taken for a duration of 28 days.

Factors related to an intention to take nPEP (Table 4)

Table 4.

Factors associated with an intention to initiate nPEP in MSM

| Variable | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior awareness of nPEP | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.6 | 1.06–2.38 | 0.03 |

| HIV knowledge | |||

| <49 | 1 | Reference | |

| 50–79 | 3.11 | 0.66–14.71 | 0.15 |

| ≥80 | 5.44 | 1.16–25.46 | 0.03 |

| Anally insertive sexual intercourse in preceding 3 months | |||

| Yes | 1 | Reference | |

| No | 1.56 | 1.04–2.34 | 0.03 |

| Have you been circumcised? | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | |

| Yes | 2.42 | 1.36–4.29 | 0.003 |

Factors associated with an intention to take nPEP were awareness of nPEP (adjusted OR=1.6, 95%CI 1.06–2.38, P=0.025), HIV knowledge with ≥80% of correct answers (adjusted OR=5.44, 95%CI 1.16–25.46, P=0.032), absence of insertive anal sex in the past 3 months (adjusted OR=1.56, 95%CI 1.04–2.34) and being circumcised (adjusted OR=2.42, 95%CI 1.36–4.29, P=0.003).

Phase II

Forty subjects were eligible for nPEP and participated in the Phase II in-depth interviews. Eleven were offered nPEP during Phase I, one subject (9%) deciding against taking it (Figure 1). Another 29 subjects who were eligible for nPEP were enrolled into Phase II after they had agreed to take it. At week 6, 32 (82%) individuals could be contacted. Of these, 31 (96.9%) had completed the nPEP course and one (3.1%) had discontinued it early due to elective surgery. Twenty-two (68.8%) individuals had experienced side effects but all were considered tolerable. All 32 individuals who had participated in the in-depth interviews and were available for follow-up had subsequent negative HIV test results.

Reasons influencing the decision to take nPEP

During the interviews at the study baseline, most of the participants who had elected to take nPEP expressed a similar level of reassurance about its efficacy and safety, particularly after receiving further information from healthcare providers. One participant reported:

The doctor said that the side effects of the medication are headache, dizziness. I did not worry too much. If exposed to HIV, I would want to try taking medication. Taking it helps me relieve my anxiety.

(Tam, 27 years old, Bangkok)

Seven out of the 40 subjects had taken nPEP previously and felt confident to take it again. They anticipated that drug side effects might occur, but believed in its effectiveness as stated below:

During my first experience with nPEP, I was stressed. I was worried about whether the medication would be effective or not. I had to tolerate the side effects of the medication, it made me feel more confident that I was reducing the risk of getting HIV infection, by taking it.

(Nut, 27 years old, Bangkok)

One participant declined to take nPEP and stated that:

If I take medication and there are side effects, I may not be able to work. As I do not have fixed working hours to take medication, it may affect my work. It is the reason why I have decided not to take the medication.

(Mark, 26 years old, Bangkok)

Changes of sexual behaviour among MSM who took nPEP

Before taking nPEP, some participants were worried about the risk of broken or split condoms during sexual intercourse as described in a statement from one of the participants:

I always use condoms. On that occasion the condom broke. My partner and I did not expect this to happen. We are now quite paranoid and cannot work. I use condoms because I feel it protects me from infections. I am now afraid to have contracted AIDS, syphilis and gonorrhoea.

(Peak, 26 years old, Bangkok)

However, 15 participants stated that they did not regularly use condoms during sexual activity. They trusted their partners and did not feel intimate when using condoms during sexual activity. Moreover, these were not always immediately available.

I usually do not use a condom when I have sex with my boyfriend because we regularly test. He is HIV negative. If I have sex with others and I do not know their HIV status, I use a condom. At the pub, I will ask people first about their HIV status. I will ask the last date and result of their HIV test.

(Pong, 26 years old, Bangkok)

After starting nPEP, all participants stated that they were more aware about using safe sex. Six participants had no sexual activities at all during nPEP. The main reasons for decreasing risky behaviour were fear of contracting HIV and worries about health consequences of taking medication. One participant's statement was as follows:

I had no sex while taking nPEP. I had sexual intercourse after I completed the nPEP course but was more concerned about HIV acquisition and used condoms. I do not want to takenPEP again. Now I use condoms for every route of sexual activity, both oral and anal.

(Joe, 35 years old, Bangkok)

After completing the course, some participants were interested in other HIV prevention methods such as pre-exposure prophylaxis or male circumcision in addition to condom use. The statement below shows a participant's opinion:

I would like to take pre-exposure prophylaxis, which is medication that protects me before risk taking. I want to take it but I am scared of the side effects in the long term. I am afraid that my liver might work too much. In the future, if taking medication can help me, I will work harder to earn money to buy it.

(Rut, 20 years old, Bangkok)

Discussion

Only 40% of high-risk Thai MSM who were seeking HIV testing at the largest VCT centre in Bangkok, Thailand showed an intention to take nPEP. This population had an HIV prevalence of 18.9% and half of them (237/450) reported multiple sexual partners and a lack of consistent condom use. Of 11 subjects who were eligible for nPEP during Phase I, 10 (91.1%) decided to take it. An additional 29 eligible individuals took nPEP. Of the 32 nPEP users who could be contacted 6 weeks later, all except one completed the course, describing a high level of adherence and tolerability to the medication; none subsequently tested positive for HIV infection.

Although the intention to take nPEP in this study, when determined by attitudes towards it, was quite low, individuals did state that when faced with an immediate risk of HIV acquisition they would be likely to take it (92%). Similarly, Mitchell et al. assessed the willingness and associated factors to take nPEP among 275 HIV-negative MSM and 58 HIV-discordant male couples in the USA and showed that 73% were extremely likely to use it if they had had unprotected sex with an HIV-positive individual [15]. Previous experience with nPEP in our study was 7%, which is higher than among MSM in the USA (3.2%) in 2013 [16] and Canada (3%) in 2016 [17]. The proportion of previous nPEP use in our study seems to be low considering the prevalence of high-risk behaviour reported, with 52.7% of individuals describing multiple partners and 40.6% of them inconsistent condom use in the past 3 months.

The multivariate analysis in our study identified four factors associated with an intention to take nPEP: nPEP awareness, high HIV knowledge, absence of recent insertive anal intercourse, and previous circumcision. nPEP awareness was documented in 60.2% of participants, a similar rate to the 64% reported in MSM surveyed in three eastern Australian states (n=16,022) [18]. However, a study of 176 US HIV-negative MSM in 2011 showed that only 28% of them had heard of it, which was much lower than in the present study [15]. In contrast, a very high proportion (82.3%) of Italian MSM (n=1874) in 2014 had knowledge about nPEP [19]. The high level of such knowledge among our MSM in Bangkok could be one of the beneficial consequences of the active HIV testing and prevention campaigns led by the TRC-ARC and several community-based organisations in Thailand over the past decade. The Adam's Love website, established by TRC-ARC since 2011 for MSM, is an online platform that successfully created awareness around HIV testing and combination HIV prevention packages, and effectively put the individuals reached online in touch with offline services [20]. In addition to the level of nPEP knowledge among at-risk individuals, the knowledge among healthcare providers could be another important barrier for nPEP uptake. A study carried out in 2008 among Ethiopian healthcare providers (n=254) demonstrated that only 16.1% had an adequate knowledge of nPEP and the lack of awareness of this prevention method was the main reason for not prescribing it after HIV exposure (33.8%) [21].

Although only half of MSM in this study had a high degree of HIV knowledge, it was higher than in the general Thai population aged 15–24 years [22], suggesting that further education campaigns are needed for the young Thai generation. Four out of 10 MSM who were eligible for nPEP and decided to take it in Phase I indicated no intention to initiate nPEP when assessed by the questionnaire but had changed their minds after the discussion with a trained counsellor. This reflects that knowledge is an extremely important factor affecting the willingness to take nPEP.

Our study found that male circumcision was another factor influencing the intention to take nPEP, which may be due to a higher level of knowledge about ways to prevent HIV infection [23,24]. Tieu et al. previously reported that 12.3% of Thai men who had visited the TRC-ARC were circumcised and that their willingness to undergo circumcision was higher after receiving education compared to baseline [25].

More of the MSM who did not practice insertive anal intercourse intended to take nPEP than those with other types of sexual activity. It is possible that these individuals knew that receptive intercourse would make them more susceptible to HIV than other modes of sexual activity, and is also consistent with a better level of HIV knowledge as shown by the number of participants intending to take nPEP in this study. Likewise Kalichman et al. have shown that MSM who practiced receptive unprotected anal and oral sex were more likely to take nPEP [26].

The results of the study qualitative component by in-depth interview at 6 weeks post-nPEP showed consistency with the data from the quantitative survey component. The results emphasised that MSM who took nPEP had prior nPEP awareness (seven had previous experience with it) and that these individuals had higher condom use following nPEP. Martin et al. have demonstrated that 76% of 397 nPEP users reported a reduction in the frequency of high-risk sexual behaviour 12 months after nPEP [27]. A long-term follow-up may provide positive data about a sustained rate of risk reduction in our cohort after nPEP.

There is limitation in our study as it is cross-sectional. Nevertheless, the longitudinal follow-up before and after nPEP in a subset of participants showed the feasibility of this preventive strategy in a Thai context. As nPEP is not available free of charge in Thailand, this could be a barrier for its uptake. However, we did not assess cost as a factor for the intention to take nPEP in this study. As the study was conducted at the VCT centre in Thailand which tests for HIV in about half of all MSM in the country, we believe that our data are representative of the Thai at-risk MSM population and of the MSM who received nPEP in Thailand. Here we have shown the feasibility of such a strategy in Thailand and that its acceptance among MSM could be high with more education on HIV and nPEP. Our data can inform the development and implementation of guidelines to scale up the combination HIV prevention services for MSM and other at-risk populations in Thailand and similar settings.

Acknowledgements

We thank all individuals who consented to participate in this study and the staff at the Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre in Bangkok for their valuable contribution to the study. We are particularly grateful to Ms Somsong Teeratakulpisarn, Dr Thep Chalermchai, Ms Sasiwan Srikhaw, Mr Sumitr Tongmuang, Mr Sirichai Jarupittaya and Ms Pairoa Praihirunkit.

Appendix 1

Demographic data questionnaire

-

1.

Date of birth ______/_______/_______ (dd/month/year)

-

2.What is your highest education?

-

□1. Primary school

-

□2. Secondary School

-

□3. High school/ basic technical school

-

□4. Advanced technical school/associate degree

-

□5. Bachelor degree

-

□6. Higher Bachelor degree

-

□7. Other ……………………………………………

-

□

-

3.What is your main occupation?

-

□1. Not working

-

□2. Student

-

□3. Company employee /factory employee

-

□4. Government/government-owned company employee

-

□5. Private business/merchant

-

□6. Commercial sex worker (in entertainment venues/restaurants)

-

□7. Others, specify……………………………………….

-

□

-

4.

What is your income………………………….. Baht/month

-

5.Have you ever take nPEP?

-

□1. No

-

□2. Not sure

-

□3. Yes If ‘Yes’ please answer question no. 6

-

□

-

6.What side effects did you experience after taking nPEP? (you may choose more than 1)

-

□1. No side effects

-

□2. Nausea

-

□3. Vomiting

-

□4. Headache

-

□5. Dizziness

-

□6. Rash

-

□7. Hepatitis

-

□8. Diarrhea

-

□9. Others, specify……………………………………….

-

□

Attitude toward nPEP

-

1.Have you ever heard about nPEP before?

-

□1. No □ 2. Yes

-

□

-

2.Have you ever taken nPEP before?

-

□1. No (please answer no. 2.1) □ 2. Yes (please answer no 2.2 and 2.3)

-

2.1What is the reason that you have not previously taken nPEP?

-

□1. No risk

-

□2. Previous risk but did not come to see the counselor within the appropriate timeframe

-

□3. Previous risk and attended counseling within the appropriate timeframe in which nPEP might be effective, but was not advised by the counselor to take nPEP.

-

□4. Previous risk and attended counseling within the appropriate timeframe in which nPEP might be effective. The counselor suggested taking nPEP, however I refused to start medication because (you may choose more than 1 option):

-

□4.1 the cost of medication was too high

-

□4.2 afraid of drug side effects

-

□4.3 did not think I would manage to take medication on time

-

□4.4 afraid that others might suspect I am HIV-positive

-

□4.5 did not believe that the medication could prevent HIV infection

-

□

-

□5. Others, specify ………………………………

-

□

-

2.2What were your reasons for deciding to ‘take nPEP’ (you may choose more 1 option)

-

□1. Received advice from the health care provider to take nPEP

-

□2. Sought nPEP within the period that nPEP was likely to be effective after risk of exposure to HIV

-

□3. Presence of risk factors (you may choose more 1 option)

-

□3.1 no use of condoms

-

□3.2 sex with an unknown person

-

□3.3 sex with a casual partner

-

□

-

□4. Was able to afford the cost of nPEP

-

□5. Was not concerned about drug side effects

-

□6. Felt able to take nPEP on time

-

□7. Friend/close acquaintance/partner wanted me to take nPEP

-

□8. Other, specify …………………………………….

-

□

-

2.3I have taken nPEP ……times and the most recent occasion was ……… (month/year)

-

□

-

3.

Have you ever known anybody who has taken nPEP?

□ 1. No □ 2. Yes -

4.

If you have risk behaviors for HIV infection, will you seek nPEP?

□ 1. No □ 2. Yes -

5.

Do you think that taking antiretroviral medication after a risk of HIV exposure can prevent HIV infection?

□ 1. No □ 2. Yes -

6.

Do you think that taking nPEP will reduce your concerns about becoming infected with HIV?

□ 1. No □ 2. Yes □ 3. Not sure -

7.

Do you think that taking antiretroviral medication after a risk of HIV exposure in order to prevent HIV infection should be available 24 hours a day?

□ 1. No □ 2. Yes □ 3. Not sure -

8.

If you want to prevent HIV infection, is receiving antiretroviral drugs to prevent infection after exposure another available option?

□ 1. No □ 2. Yes □ 3. Not sure -

9.

Do you believe that the antiretroviral drugs used to prevent HIV infection are effective in preventing HIV infection?

□ 1. No □ 2. Yes □ 3. Not sure -

10.

Do you trust that your healthcare provider is dispensing antiretroviral drugs to prevent infection after exposure appropriately?

□ 1. No □ 2. Yes □ 3. Not sure -

11.

Do you have confidence in the standard of treatment of the clinic at which you are accessing treatment?

□ 1. No □ 2. Yes □ 3. Not sure -

12.

Can you take antiretroviral drugs regularly in accordance with the advice of your doctor?

□ 1. No □ 2. Yes □ 3. Not sure -

13.

Are you afraid that others will think that you have HIV if you are take nPEP?

□ 1. No □ 2. Yes □ 3. Not sure -

14.

If someone were to know that you are taking nPEP, will this have an impact on your life or your job?

□ 1. No □ 2. Yes □ 3. Not sure -

15.

If someone were to know that you are taking nPEP, do you think that others will gossip about you in negative way?

□ 1. No □ 2. Yes □ 3. Not sure -

16.

If you were to be raped and were at risk of HIV infection, would you be afraid and not seek medical attention discuss the prevention of HIV infection?

□ 1. No □ 2. Yes □ 3. Not sure -

17.

Do you think that other men who have sex with men do not test for HIV because they fear that others will know that they are MSM?

□ 1. No □ 2. Yes □ 3. Not sure

Knowledge and prevention of HIV questionnaire

| Question | Yes | No | Not sure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of HIV | |||

| Can you get HIV by having sexual intercourse with an infected person? | |||

| Can HIV be transmitted from mother to child? | |||

| Is HIV is a curable disease if diagnosed in early stage? | |||

| Can you get HIV by sharing a bathroom, toilet, clothes or by kissing an infected person? | |||

| Can HIV be spread via mosquito or insect bites? | |||

| Can you get HIV via blood transfusion or from receiving other blood products that are infected with HIV? | |||

| Can you get HIV by sharing needles with an infected person? | |||

| Can you get HIV by touching or eating with an infected person? | |||

| Knowledge about HIV prevention | |||

| Can you get HIV by having sexual intercourse without using a condom with a person who you know very well? | |||

| Can you prevent HIV infection by always using a condom during sexual intercourse? | |||

| Does ejaculating outside prevent HIV infection? | |||

| Can you prevent HIV infection by avoiding sexual intercourse with sex workers? | |||

| Can you prevent HIV infection by choosing to have sexual intercourse with only person who look healthy? | |||

| Can you prevent HIV infection by avoiding sexual intercourse? | |||

| Can you prevent HIV infection by washing your genitals after having sexual intercourse every time? | |||

| Does having an STI in combination with risky sexual behavior with an infected person increase your chance of HIV infection? | |||

Knowledge about nPEP

-

1.Where can you buy antiretroviral medication?

-

□1. General pharmacy

-

□2. Hospital

-

□3. Private clinic

-

□

-

2.Taking nPEP may prevent HIV infection, but within how many hours of the risk the risk of exposure must it be taken?

-

□1. 72 hours (3 days)

-

□2. 96 hours (4 days)

-

□3. 120 hours (5 days)

-

□

-

3.How should nPEP be taken?

-

□1. Continually take for 7 days

-

□2. Continually take for 14 days

-

□3. Continually take for 28 days

-

□

-

4.

Can antiretroviral medication cause side effects in people who take it?

□ 1. Yes □ 2. No □ 3. Not sure

Sexual behavior and substance use questionnaire

-

1.

The age at your first sexual intercourse was ………… years

(Please check this box □ if you have never had sexual intercourse)

Please specify the routes of sexual intercourse that you have used a regular basis (please include routes of sexual intercourse over the course of your whole lifetime; you may choose more 1 option)Insertive □ 1. vaginal □ 2. rectal □ 3. oral Receptive □ 4. rectal □ 5. oral -

2.In the past 3 months, what is your risk level for getting HIV infection?

-

□1. No risk (no sexual intercourse)

-

□2. Minimal risk (sexual intercourse with a single and stable partner regardless of condom use OR with multiple partners with consistent condom use)

-

□3. Moderate risk (sexual intercourse with multiple partners with occasional condom use)

-

□4. High risk (sexual intercourse with HIV-positive partner(s) regardless of condom use OR sexual intercourse with multiple partners and no condom use)

-

□

-

3.During the past 3 months, how many sexual partners have you had?

Male □ 1. No sexual partners □ 2. ……partners □ 3. Decline to answer Female □ 1. No sexual partners □ 2. ……partners □ 3. Decline to answer Transgender □ 1. No sexual partners □ 2. ……partners □ 3. Decline to answer If for question 3, you answered ‘No sexual partners’ for all three categories, please skip to question 12

-

4.During the past 3 months, which countries have your partners come from? (you may choose more than 1 answer)

-

□1. Thailand

-

□2. Other countries, please specify……………………..

-

□3. Decline to answer

-

□

-

5.In the past 3 months, what routes of sexual intercourse have you used? (you may choose more 1 option)

-

□1. Anally receptive

-

□2. Anally insertive

-

□3. Vaginally insertive

-

□4. Orally receptive

-

□5. Orally insertive

-

□

-

6.In the past 3 months, have you used condoms with your regular sexual partner?

-

□1. No sexual intercourse with regular sexual partner

-

□2. No

-

□3. Sometime

-

□4. Every time

-

□5. Decline to answer

-

□

-

7.In the past 3 months, have you used condoms with your casual sexual partner?

-

□1. No sexual intercourse with casual sexual partner

-

□2. No

-

□3. Sometimes

-

□4. Every time

-

□5. Decline to answer

-

□

-

8.In the past 3 months, have you used condoms with commercial sex workers?

-

□1. No sexual intercourse with commercial sex workers

-

□2. No

-

□3. Sometimes

-

□4. Every time

-

□5. Decline to answer

-

□

-

9.In the past 3 months, have you used condoms with people who give you money/goods?

-

□1. No sexual intercourse with people who give me money/goods

-

□2. No

-

□3. Sometimes

-

□4. Every time

-

□5. Decline to answer

-

□

-

10.In the past 3 months, have you used condoms with a sexual partner who is an illicit intravenous drug user?

-

□1. No sexual intercourse with a sexual partner who is an illicit intravenous drug user

-

□2. No

-

□3. Sometimes

-

□4. Every time

-

□5. Decline to answer

-

□6. Don't know if my partner is an illicit intravenous drug user

-

□

-

11.In the past 3 months, have you taken alcohol before or during a sex act?

-

□1. I do not drink alcohol

-

□2. Sometimes

-

□3. Every time

-

□4. Decline to answer

-

□

-

12.In the past 3 months, have you used psychoactive drugs/ illicit drugs before or a during sex act?

-

□1. No

-

□2. Yes

-

□1. Methamphetamine/Amphetamine (ice, crystal meth, speed)

-

□2. Ecstasy

-

□3. Poppers

-

□4. Not sure what the instance

-

□

-

□3. Decline to answer

-

□

-

13.In the past 3 months, have you shared needles with others when using illicit intravenous drugs?

-

□1. Never used illicit intravenous drugs

-

□2. Have used illicit intravenous drugs, but not in the past 3 months

-

□3. Have used illicit intravenous drugs, but did not share needles with others

-

□4. Have used illicit intravenous drugs and also shared needles with others

-

□5. Decline to answer

-

□

-

14.In the past 3 months, have you had any symptoms of sexually transmitted diseases such as discomfort on urination, discharge from the urethra, blisters or other lesiosns on the genitalia or have you been diagnosed with a sexually transmitted disease such as warts, herpes, syphilis, gonorrhea or chlamydia?

-

□1. No

-

□2. Yes

-

□3. Not sure

-

□4. Decline to answer

-

□

-

15.Have you been circumcised?

-

□1. I was circumcised at ………….. years of age

-

□2. No

-

□3. Decline to answer

-

□

Appendix 2

| Attitudes regarding nPEP | Did not intend to initiate nPEP | Intend to initiate nPEP | Total | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total=269 | Total=181 | Total=450 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Have you ever known anybody who has taken nPEP? | 44(16.4) | 32(17.7) | 76(16.9) | 0.80 |

| If you have risk behaviors for HIV infection, will you seek nPEP? | 246(91.5) | 170(93.9) | 416(92.4) | 0.37 |

| Do you think that taking nPEP will reduce your concerns about becoming infected with HIV? | ||||

| - No | 95(35.4) | 26(14.4) | 121(27.0) | <0.001 |

| - Yes | 173(64.6) | 155(85.6) | 328(73.0) | |

| *Do you think that taking antiretroviral medication after a risk of HIV exposure can prevent HIV infection? | ||||

| - No | 193(7.1) | 0 | 193(4.9) | <0.001 |

| - Yes | 76(28.3) | 181(100) | 257(57.1) | |

| *Do you think that taking antiretroviral medication after a risk of HIV exposure in order to prevent HIV infection should be available 24 hours a day? | ||||

| - No | 81(30.2) | 0 | 81(18.0) | <0.001 |

| - Yes | 187(69.8) | 181(100) | 368(82.0) | |

| *If you want to prevent HIV infection, is receiving antiretroviral drugs to prevent infection after exposure another available option? | ||||

| - No | 37(13.8) | 0 | 37(8.2) | <0.001 |

| - Yes | 232(86.2) | 181(100) | 413(91.8) | |

| *Do you believe that the antiretroviral drugs used to prevent HIV infection are effective in preventing HIV infection? | ||||

| - No | 123(45.7) | 0 | 123(27.3) | <0.001 |

| - Yes | 146(54.3) | 181(100) | 327(72.7) | |

| *Do you trust that your healthcare provider is dispensing antiretroviral drugs to prevent infection after exposure appropriately? | ||||

| - No | 84(31.2) | 0 | 84(18.7) | <0.001 |

| - Yes | 185(68.8) | 181(100) | 366(81.3) | |

| *Do you have confidence in the standard of treatment of the clinic at which you are accessing treatment? | ||||

| - No | 39(14.6) | 0 | 39(8.7) | <0.001 |

| - Yes | 228(85.4) | 181(100) | 409(91.3) | |

| *Can you take antiretroviral drugs regularly in accordance with the advice of your doctor? | ||||

| - No | 50(18.7) | 0 | 50(11.1) | <0.001 |

| - Yes | 218(81.3) | 181(100) | 399(88.9) | |

| Questions about stigmatization | ||||

| Are you afraid that others will think that you have HIV if you are taking nPEP? | ||||

| - No | 150(56.0) | 91(50.3) | 241(53.7) | 0.24 |

| - Yes | 118(44.0) | 90(49.7) | 208(46.3) | |

| If someone were to know that you are taking nPEP, will this have an impact on your life or your job? | ||||

| - No | 154(57.2) | 85(47.0) | 239(53.1) | 0.03 |

| - Yes | 115(42.8) | 96(53.0) | 211(46.9) | |

| If someone were to know that you are taking nPEP, do you think that others will gossip about you in negative way? | ||||

| - No | 86(32.0) | 49(27.1) | 135(30.0) | 0.27 |

| - Yes | 183(68.0) | 132(72.9) | 315(70.0) | |

| If you were to be raped and were at risk of HIV infection, would you be afraid and not seek medical attention discuss the prevention of HIV infection? | ||||

| - No | 233(86.6) | 171(94.5) | 404(89.8) | 0.007 |

| - Yes | 36(13.4) | 10(5.5) | 46(10.2) | |

| Do you think that other men who have sex with men do not test for HIV because they fear that others will know that they are MSM? | ||||

| - No | 161(59.9) | 98(54.1) | 259(57.6) | 0.23 |

| - Yes | 108(40.1) | 83(45.9) | 191(42.4) | |

| Concerning stigmatisation(answering ‘Yes’ to 3 out of 5 questions) | ||||

| - No | 159(59.1) | 101(55.8) | 260(57.8) | 0.49 |

| - Yes | 110(40.9) | 80(44.2) | 190(42.2) | |

These questions were used to define intention to take nPEP

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the positions of the US Army or the Department of Defense.

Funding

This project was supported by the Fogarty International Center and the National Institutes of Health under NIH research training grant #R25TW009345.

References

- 1. UNAIDS 2016. Global AIDS Update. Available at: www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2016/Global-AIDS-update-2016 ( accessed June 2017).

- 2. Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health 2008. The Asian Epidemic Model (AEM) Projections for HIV/AIDS in Thailand: 2005–2025. Available at: hivhealthclearinghouse.unesco.org/library/documents/asian-epidemic-model-aem-projections-hivaids-thailand-2005–2025 ( accessed June 2017).

- 3. Bureau of Epidemiology, Department of Disease Control Ministry of Public Health HIV/AIDS situation in Thailand 2016. Available at: http://203.157.15.110/boe/surveillance.php?idx=c2l0#sur-href ( accessed June 2017).

- 4. Griensven F, Holtz TH, Thienkrua W et al. Temporal trends in HIV-1 incidence and risk behaviours in men who have sex with men in Bangkok, Thailand, 2006–13: an observational study. Lancet HIV 2015; 2: e64– 70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre 2016. Our services: Thai Red Cross Anonymous Clinic. Available at: http://en.trcarc.org/?slide=slide-4 ( accessed June 2017).

- 6. Arroyo MA, Phanuphak N, Krasaesub S et al. HIV type 1 molecular epidemiology among high-risk clients attending the Thai Red Cross Anonymous Clinic in Bangkok, Thailand. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2010; 26: 5– 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ananworanich J, Schuetz A, Vandergeeten C et al. Impact of multi-targeted antiretroviral treatment on gut T cell depletion and HIV reservoir seeding during acute HIV infection. PLoS One 2012; 7: e33948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Griensven F, Thienkrua W, Sukwicha W et al. Sex frequency and sex planning among men who have sex with men in Bangkok, Thailand: implications for pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis against HIV infection. J Int AIDS Soc 2010; 13: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ruxrungtham K, Chokephaibulkit K, Chetchotisakd P et al. Thailand National Guidelines on HIV/AIDS Treatment and Prevention 2014. 1 ed Bangkok: Agricultural Cooperative Federation of Thailand's Printing Co., Ltd.; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith DK, Grohskopf LA, Black RJ et al. Antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV in the United States: recommendations from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. MMWR Recomm Rep 2005; 54: 1– 20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Savage J. National guidelines for post-exposure prophylaxis after non-occupational exposure to HIV. Sex Health 2007; 4: 277– 283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Announcement: updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV – United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65: 458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S.. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd edn New York: John Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Turunen H, Perala ML, Merilainen P.. Modification of Colaizzi's phenomenological method; a study concerning quality care. Hoitotiede 1994; 6: 8– 15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mitchell JW, Sophus AI, Petroll AE.. HIV-negative partnered men's willingness to use non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis and associated factors in a US sample of HIV-negative and HIV-discordant male couples. LGBT health 2016; 3: 146– 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oldenburg CE, Perez-Brumer AG, Hatzenbuehler ML et al. State-level structural sexual stigma and HIV prevention in a national online sample of HIV-uninfected MSM in the United States. AIDS 2015; 29: 837– 845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lin SY, Lachowsky NJ, Hull M et al. Awareness and use of nonoccupational post-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in Vancouver, Canada. HIV Med 2016; 17: 662– 673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zablotska IB, Prestage G, Holt M et al. Australian gay men who have taken non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV (PEP) are in need of effective HIV prevention methods. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011; 58: 424– 428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Prati G, Zani B, Pietrantoni L et al. PEP and TasP awareness among Italian MSM, PLWHA, and high-risk heterosexuals and demographic, behavioral, and social correlates. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0157339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Anand T, Nitpolprasert C, Ananworanich J et al. Innovative strategies using communications technologies to engage gay men and other men who have sex with men into early HIV testing and treatment in Thailand. J Virus Erad 2015; 1: 111– 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tebeje B, Hailu C.. Assessment of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis use among health workers of governmental health institutions in Jimma Zone, Oromiya Region, Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 2010; 20: 55– 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thailand National AIDS Committee 2012. 2012 Thailand AIDS Response Progress Report: Status At A Glance. Bangkok Available at: http://www.aidsdatahub.org/sites/default/files/documents/UNGASS_2012_Thailand_Narrative_Report.pdf ( accessed June 2017).

- 23. Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks JJ, Volmink J.. Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009: CD003362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007; 369: 643– 656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tieu HV, Phanuphak N, Ananworanich J et al. Acceptability of male circumcision for the prevention of HIV among high-risk heterosexual men in Thailand. Sex Transm Dis 2010; 37: 352– 355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kalichman SC. Post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection in gay and bisexual men. Implications for the future of HIV prevention. Am J Prev Med 1998; 15: 120– 127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Martin JN, Roland ME, Neilands TB et al. Use of postexposure prophylaxis against HIV infection following sexual exposure does not lead to increases in high-risk behavior. AIDS 2004; 18: 787– 792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]