Abstract

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is a noninvasive imaging method for measuring the diffusion properties of the underlying white matter tracts through which epileptiform activity is propagated. This study investigates the structural abnormalities quantified by DTI in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (mTLE). Fiber tracts passing through 54 anatomical sites in 12 adult mTLE patients and 12 age- and gender- matched controls were identified using DTI tractography. DTI nodal degree (ND) and laterality index were then calculated. ND laterality, after Bonferroni adjustment, showed significant differences for right versus left mTLE in gyrus rectus, insular cortex, precuneus and superior temporal gyrus (p<0.025). None of these anatomical sites showed statistically significant differences in ND laterality between right and left sides of the controls. Laterality models determined by logistic regression on the ND laterality data agreed with the side of epileptogenicity as it pertained to the gyrus rectus, insular cortex, precuneus and superior temporal gyrus for 89%, 72%, 83% and 92% of the patients, respectively. Combining the laterality measures in these four anatomical sites improved the results further with correct lateralization of 100% for all patients. The proposed methodology for using DTI connectivity to investigate diffusion abnormalities related to focal epileptogenicity and propagation can provide a further means of noninvasive lateralization.

I. INTRODUCTION

Over sixty-five million people worldwide and three million people in the United States are diagnosed with epilepsy, 15 to 20% of which remain medically refractory in spite of antiepileptic medical therapy [1]. Mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (mTLE) is the most common form of surgically remediable focal epilepsy, accounting for 60 – 75% of patients undergoing surgery for medically refractory epilepsy [2]. Intracranial electroencephalography (icEEG) optimizes localization of focal epileptogenicity, although it incurs great expense, and carries risks of infection, intracranial hemorrhage and elevated intracranial pressure [3]. This has inspired further work with noninvasive neuroimaging methods to provide better definition of focal epileptogenicity and obviate the need for invasive study in some patients and perhaps altogether [4, 5].

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is a noninvasive MRI technique which quantifies diffusion properties of water molecules and the degree and direction of anisotropy in biological tissues. Cerebral tissue has highly heterogeneous diffusion properties due to regional differences in nerve fiber density, concentrations of macromolecules and intracellular organelles and myelination density. Tractography can identify virtual pathways of major nerve fiber tracts and quantify abnormalities in these tracts that underlie disruption of the microstructural environment with subsequent reduction of diffusion anisotropy [6, 7].

This paper presents a method by which DTI connectivity can be used in such a fashion to investigate a putative epileptogenic network. We hypothesize that DTI nodal degree (ND) laterality can contribute to noninvasive lateralization of mTLE patients.

II. Materials and Methods

A. Patients and Treatment

Twelve consecutive adult patients with refractory TLE (six females) who had undergone DTI were selected for this study. Each had undergone inpatient video-electroencephalography, MRI, neuropsychological evaluation and intracarotid sodium amobarbital injection for evaluation of verbal memory capacity. Those lacking sufficient lateralization by this stage underwent further study by intracranially implanted electrodes for extraoperative electroencephalography. Patients were excluded if their MRI indicated cortical dysplasia, tumor, dilated ventricles or previous resection. Four patients had pathologically-proven hippocampal sclerosis. All patients underwent surgical resection and achieved an Engel class I outcome (i.e., seizure-free one year postoperatively). Twelve age- and gender- matched healthy control subjects without neurologic disorders underwent DTI study with the same parameters.

B. Diffusion Tensor Imaging

All subjects underwent preoperative imaging in a 3.0T MRI system (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, U.S.A.) using a standardized protocol for image acquisition. Coronal T1-weighted images were acquired using the spoiled gradient echo (SPGR) protocol with TR/TI/TE=10400/4500/300 ms, flip angle=15°, near cubic voxel size=0.9375 × 0.9375 × 1.00 mm3, imaging matrix 256×256, field-of-view (FOV) of 240 × 240 mm2 that includes the entire skin surface of the head for construction of head and cortical model for MEG analysis. DTI images (b-value of ) along with a set of null images (b-value of ) were acquired using echo planar imaging (EPI) with TR/TI/TE=7500/0/76 ms, flip angle = 90°, voxel size = 1.96×1.96×2.6 mm3, imaging matrix 128×128, FOV of 240 × 240 mm2 and 25 diffusion gradient directions.

C. Brain Model

A brain model was constructed for each individual’s T1-weighted high-resolution volumetric MR image. We used a probabilistic brain atlas composed of 56 structures from manually delineated MRI data constructed by Shattuck et al. (2008) as a standard volumetric brain model with each location specified in MNI305 coordinates. This atlas contains all cerebral lobes and, specifically, the right and left hippocampi, limbic gyri, insular cortices, caudate, putamen, cerebellum and brainstem. Excluding the cerebellum and brainstem reduced the number of anatomical regions to 27 in each cerebral hemisphere [8].

D. DTI Preprocessing

The DTI data were prepared by interpolation to a cubic voxel size of 1.96 mm and tensor, fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity (MD) calculation [9]. For the purpose of tractography, the principal diffusion direction (PDD), the eigenvector corresponding to the largest eigenvalue of the tensor, was also calculated from the tensor. Using an affine registration tool (FLIRT, FSL) [10] T1-weighted images and subsequently the extracted anatomical regions were coregistered to the DTI data to establish the input ROI for tractography.

E. DTI Tractography and Connectivity

Tractography offers a method of identifying diffusion parameters associated with white matter tracts that may facilitate the propagation of epileptic activity. The tractography was performed automatically using FACT Streamline [11] implemented in a home-made tractography application between all 54 anatomical regions (Figs. 1 and 2). Streamline fiber tracking parameters comprised an FA threshold of 0.10, minimum fiber length of 0.10 mm, and maximum allowed angle bending between two fiber segments of 45°. The FA threshold eliminated the inclusion of gray matter to allow comparison of diffusion properties of only the resultant white matter tracts. The minimum fiber length threshold eliminated the irrelevant minor fibers that are essentially constructed from DTI noise. The maximum allowed angle threshold guaranteed a smooth fiber trajectory expected in practice. With the reconstructed fibers, a connectivity matrix was constructed for each subject by calculating the mean FA value of the voxels of all fibers connecting each pair of regions:

| (1) |

where k represents the kth fiber connecting the brain sites i,j.

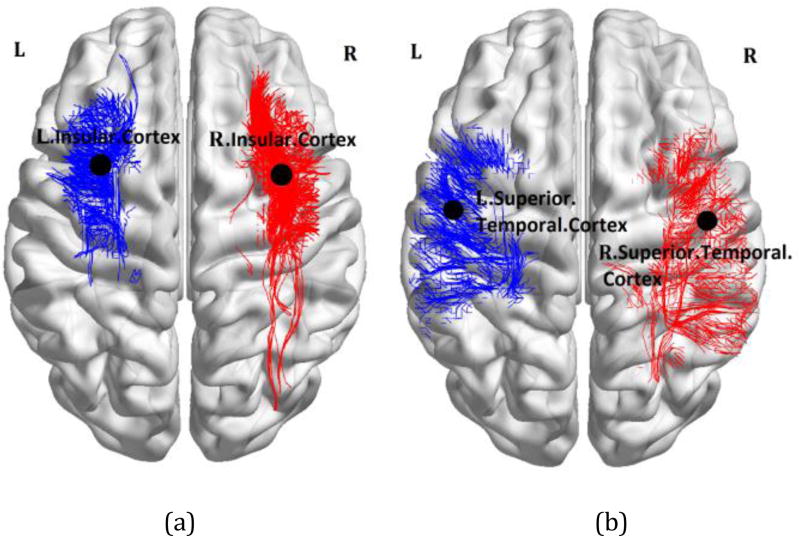

Figure 1.

Tractography results overlaid on the MNI registered brain [13], performed between the insular cortex (a) and the superior temporal gyrus (b) as the input ROI and all other anatomical ROIs for a single patient with left mTLE.

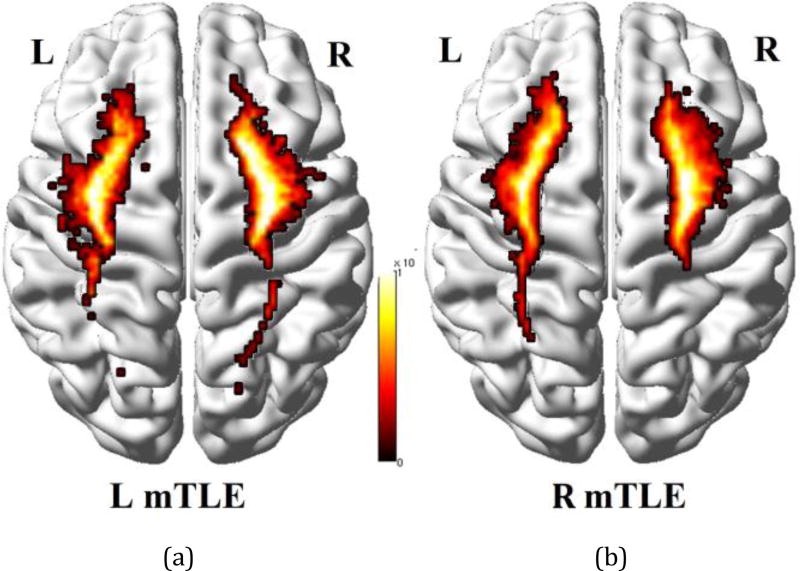

Figure 2.

Density map of tracts overlaid on the MNI registered brain [13], between the insular cortex and all other anatomical regions averaged on the left (a) and right mTLE patients (b).

E. Nodal Degree Laterality

The ND of a brain site i is defined as [12]:

| (2) |

where C and S denote the cohorts of controls and all subjects, respectively. The ND laterality was computed to determine which hemisphere exhibited the higher ND:

| (3) |

where ND(i) and ND(i + 27) represent the ND for the site i in the left and right hemispheres, respectively.

F. Statistical Analysis

Two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (RMANOVA) was used to examine the relationships of the ND laterality measurements with the brain regions (i.e., a repeated factor) and the mTLE laterality type (i.e., a fixed factor) [14]. Of particular interest were tests for interaction between a region and a laterality type, since a significant interaction would imply that separate one-way ANOVAs are required to assess mTLE laterality type.

For each region, one-way ANOVA on the mTLE laterality type was performed and multiple comparisons were addressed by Bonferroni adjustments for two pairwise comparisons between laterality types (p<0.05/2=0.025). However, the one-way ANOVAs were considered statistically significant only if the overall ANOVA F-test for all mTLE laterality types was also significant after a multiple comparisons adjustment (p<0.05/27=0.0019).

G. Lateralization Response-Driven Models

The statistically significant ND laterality measures between the left and right mTLE cohorts were considered as multivariate independent variables and incorporated into the development of response-driven models of laterality using logistic function regression [15]. In order to assess how the multinomial logistic function generalized to an independent dataset and how accurately this response model performed in practice, a cross-validation was performed using the ‘leave-one-out’ approach [16]. The probability of detection on the test data was then calculated [17, 18].

III. RESULTS

A. Nodal Degree Laterality

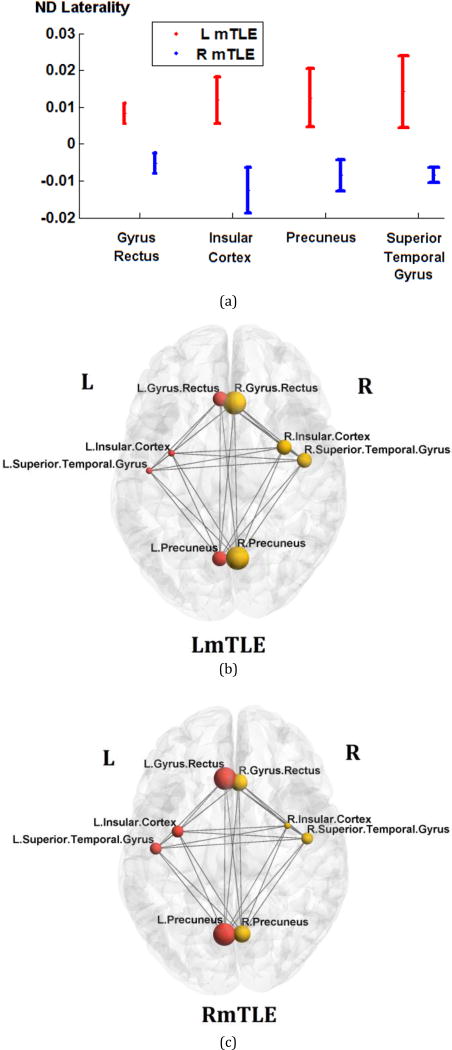

The ages of the male and female subjects across any of the right and left mTLE and control cohorts were statistically comparable. Two-way RMANOVA demonstrated significant interaction in ND laterality between both regional and mTLE laterality types (p<0.001). The ND laterality showed significant differences in the gyrus rectus, insular cortex, precuneus and the superior temporal gyrus in both overall ANOVA F-test for mTLE laterality types and t-tests between pairs of right and left mTLE, after Bonferroni adjustments (p<0.0019 and p<0.025, respectively; Fig. 3a). None of these anatomical sites showed statistically significant differences in nodal degree laterality between right and left sides of the controls. Figure 1 shows the tractography results overlaid on the MNI registered brain, performed from the insular cortex and the superior temporal gyrus for a single patient with left mTLE. Figure 2 shows the average density map of tracts originating from insular cortex, for both cohorts of left and right mTLE patients. Note that fewer tracts were reconstructed posteriorly originating from the ipsilateral insular cortex, compared to its contralateral side to the epileptogenicity. Figures 3b and 3c show the mean nodal degree in the gyrus rectus, insular cortex, precuneus and the superior temporal gyrus for the left and right mTLE patient cohorts, respectively.

Figure 3.

ND laterality in gyrus rectus, insular cortex, precuneus, and superior temporal gyrus, where significant differences between the right and left mTLE patients were seen. (a) The error bars represent the standard error of the ND laterality. (b)–(c) The spheres and lines overlaid upon the MNI registered brain [13] show the significant cortical sites and their corresponding connections, respectively. The right and left cortical sites are shown in yellow and red, respectively. The mean nodal degrees are represented by the size of the spheres.

B. mTLE Lateralization Models

The laterality was modeled by logistic regression of the ND laterality data in the gyrus rectus, insular cortex, precuneus, and superior temporal gyrus. By averaging over 12 repetitions of leave-one-out cross validation, the probability of detection achieved 0.89±0.04, 0.72±0.04, 0.83±0.04 and 0.92±0.02 for the laterality models of the gyrus rectus, insular cortex, precuneus, and superior temporal gyrus, respectively. Combining the laterality measures in these four anatomical sites improved lateralization results to 100% of the patients.

IV. Discussion and conclusion

This study described a method of using DTI connectivity to investigate white matter fibers associated with epileptiform activity in the mTLE patients. It shows that the hemisphere containing the epileptic focus in the mTLE patients may be determined using a connectivity-based laterality model involving these brain areas.

Previous studies suggest that abnormal water diffusion, identified as changes in FA or MD, may be found in identified white matter tracts of epileptic networks in both temporal and extratemporal structures [14, 19]. Investigation of structural connectivity in mTLE using DTI has shown similar promise in lateralizing epileptogenicity [20]. In this context, the brain is modeled as a network of connected nodes. The nodes are selected based upon structural and functional parcellation of the brain. The connectivity matrix is then established and the entire matrix or specific connections compared between groups of individuals. Major differences may be found between groups at the expense of higher sampling volume and more complex statistical analysis [21]. An alteration in structural connectivity of the temporal pole and the inferolateral and perisylvian cortices has been identified in unilateral mTLE [22]. A decrease in structural connectivity with DTI, both within-module and between-module, throughout the default mode network (DMN) has also been observed in mTLE compared to nonepileptic subjects [12, 23, 24]. A widespread increase in global network efficiency is seen within the DMN in mTLE, implying a facilitation of propagation of epileptogenicity throughout the region. Some reorganization of the limbic system in mTLE has also been identified [25].

With increasing use of neuroimaging biomarkers, noninvasive investigational techniques may ultimately supplant invasive monitoring as a means of localizing focal epileptogenicity and establishing surgical candidacy.

Acknowledgments

Research supported in part by NIH grant R01-EB013227.

Contributor Information

Mohammad R. Nazem-Zadeh, Departments of Research Administration and Radiology, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI, USA (phone: 313-874-4349;) Control and Intelligent Processing Center of Excellence (CIPCE), School of Electrical and Computer, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran.

Susan M. Bowyer, Departments of Neurology, Radiology, Radiation Oncology, and Research Administration, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI, USA

John E. Moran, Departments of Neurology, Radiology, Radiation Oncology, and Research Administration, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI, USA

Esmaeil Davoodi-Bojd, Departments of Neurology, Radiology, Radiation Oncology, and Research Administration, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI, USA.

Andrew Zillgitt, Departments of Neurology, Radiology, Radiation Oncology, and Research Administration, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI, USA.

Hassan Bagher-Ebadian, Departments of Neurology, Radiology, Radiation Oncology, and Research Administration, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI, USA.

Fariborz Mahmoudi, Departments of Neurology, Radiology, Radiation Oncology, and Research Administration, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI, USA.

Kost V. Elisevich, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Spectrum Health Medical Group, Grand Rapids, MI, USA

Hamid Soltanian-Zadeh, Departments of Neurology, Radiology, Radiation Oncology, and Research Administration, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI, USA.

References

- 1.Kohrman MH. What is Epilepsy? Clinical Perspectives in the Diagnosis and Treatment. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2007;24(2):87–95. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e3180415b51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engel J., Jr Surgery for seizures. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;334(10):647–653. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603073341008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arya R, Mangano FT, Horn PS, Holland KD, Rose DF, Glauser TA. Adverse events related to extraoperative invasive EEG monitoring with subdural grid electrodes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsia. 2013;54(5):828–839. doi: 10.1111/epi.12073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aghakhani Y, Liu X, Jette N, Wiebe S. Epilepsy surgery in patients with bilateral temporal lobe seizures: A systematic review. Epilepsia. 2014 doi: 10.1111/epi.12856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J, Liu Q, Mei S, Zhang X, Liu W, Chen H, Xia H, Zhou Z, Wang X, Li Y. Identifying the affected hemisphere with a multimodal approach in MRI-positive or negative, unilateral or bilateral temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2014;10:71. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S56404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rugg-Gunn FJ. Diffusion imaging in epilepsy. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7(8):1043–54. doi: 10.1586/14737175.7.8.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yogarajah M, Duncan JS. Diffusion-based magnetic resonance imaging and tractography in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shattuck DW, Mirza M, Adisetiyo V, Hojatkashani C, Salamon G, Narr KL, Poldrack RA, Bilder RM, Toga AW. Construction of a 3D probabilistic atlas of human cortical structures. Neuroimage. 2008;39(3):1064–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nazem-Zadeh MR, Chapman CH, Lawrence TL, Tsien CI, Cao Y. Radiation therapy effects on white matter fiber tracts of the limbic circuit. Medical physics. 2012;39(9):5603–5613. doi: 10.1118/1.4745560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17(2):825–841. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mori S, van Zijl PC. Fiber tracking: principles and strategies - a technical review. NMR Biomed. 2002;15(7–8):468–80. doi: 10.1002/nbm.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeSalvo MN, Douw L, Tanaka N, Reinsberger C, Stufflebeam SM. Altered Structural Connectome in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Radiology. 2014;270(3):842–848. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13131044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xia M, Wang J, He Y. BrainNet Viewer: a network visualization tool for human brain connectomics. PloS one. 2013;8(7):e68910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nazem-Zadeh M-R, Elisevich K, Air EL, Schwalb JM, Divine G, Kaur M, Wasade VS, Mahmoudi F, Shokri S, Bagher-Ebadian H, Soltanian-Zadeh H. DTI-based Response-Driven Modeling of mTLE Laterality. NeuroImage Clinical. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosmer DW, Jr, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression. 2013 Wiley.com.

- 16.Picard RR, Cook RD. Cross-validation of regression models. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1984;79(387):575–583. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nazem-Zadeh M-R, Schwalb JM, Bagher-Ebadian H, Jafari-Khouzani K, Elisevich KV, Soltanian-Zadeh H. A Bayesian averaged response-driven multinomial model for lateralization of temporal lobe epilepsy. Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), 2014 IEEE 11th International Symposium on. 2014:197–200. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2014.6944895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nazem-Zadeh M-R, Elisevich KV, Schwalb JM, Bagher-Ebadian H, Mahmoudi F, Soltanian-Zadeh H. Lateralization of temporal lobe epilepsy by multimodal multinomial hippocampal response-driven models. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2014;347(1):107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nazem-Zadeh MR, Schwalb JM, Elisevich KV, Bagher-Ebadian H, Soltanian-Zadeh H. Lateralization of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy using a Novel Uncertainty Analysis of MR Diffusion in Hippocampus, Cingulum, and Fornix, and Hippocampal Volume and FLAIR Intensity, in Gordon Research Conference on Mechanisms of Epilepsy & Neural Synchronization. West Dover, VT, USA: 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lemkaddem A, Daducci A, Kunz N, Lazeyras F, Seeck M, Thiran J-P, Vulliémoz S. Connectivity and tissue microstructural alterations in right and left temporal lobe epilepsy revealed by diffusion spectrum imaging. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2014;5:349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zalesky A, Fornito A, Bullmore ET. Network-based statistic: identifying differences in brain networks. Neuroimage. 2010;53(4):1197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Besson P, Dinkelacker V, Valabregue R, Thivard L, Leclerc X, Baulac M, Sammler D, Colliot O, Lehericy S, Samson S, Dupont S. Structural connectivity differences in left and right temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroimage. 2014;100:135–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiang S, Haneef Z. Graph theory findings in the pathophysiology of temporal lobe epilepsy. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2014;125(7):1295–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaessen MJ, Jansen JF, Vlooswijk MC, Hofman PA, Majoie HM, Aldenkamp AP, Backes WH. White matter network abnormalities are associated with cognitive decline in chronic epilepsy. Cerebral cortex. 2011:bhr298. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonilha L, Nesland T, Martz GU, Joseph JE, Spampinato MV, Edwards JC, Tabesh A. Medial temporal lobe epilepsy is associated with neuronal fibre loss and paradoxical increase in structural connectivity of limbic structures. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-302476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]