Abstract

Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia is a rare vascular disease characterized by multiple erythematous to violaceous papules, commonly present on the head and neck region. We report a case of a 23-year-old female who presented with multiple, erythematous asymptomatic papules on the preauricular region and pinna, which on biopsy was suggestive of angiolymphoid hyperplasia. The lesions were treated with a novel combination of radiofrequency ablation and topical timolol. The lesions healed without scarring and there was no recurrence on 1 year follow up.

Keywords: Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia, Kimura's disease, timolol, radiofrequency ablation, vascular malformation

Introduction

Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia (ALHE) was first described by Wells and Whimster.[1] ALHE affects young women with no racial predilection. It presents as multiple erythematous or violaceous papules or nodules on the head and neck region.[1] The etiopathogenesis is still unknown, however, it is considered to be a vascular malformation with proliferation of vessels in response to trauma, external otitis media, pregnancy or low T cell clonality.[1] Histopathology shows vascular proliferation with large epithelioid or histoid endothelial cells with infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils.[1] The condition is chronic and resistant to treatment.

Case Report

A 23-year-old female presented to us with multiple skin-colored to erythematous lesions on her right preauricular region and pinna for the last 5 years. The lesions were associated with itching and bleeding on scratching. She denied any history of trauma, fever or infection. On examination, there were multiple erythematous and skin-colored papules of sizes varying from 0.2 cm × 0.2 cm to 0.5 cm × 0.3 cm present on the right auricular and preauricular skin [Figure 1]. No lymphadenopathy was noted. Her hematological (including absolute eosinophil count) and biochemical investigations were normal. Skin biopsy from the papule showed orthokeratosis, follicular plugging and mild acanthosis. Dermis showed a nodular lesion comprising proliferating small vascular channels lined by plump endothelial cells. Few of the vessels showed fibrinoid necrosis. These blood vessels were surrounded by inflammatory infiltrate comprising lymphocytes, plasma cells and few eosinophils [Figure 2]. Based on the above mentioned findings, a diagnosis of ALHE was made. The patient was started on a combination therapy of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and topical timolol maleate solution (0.5%) because of the vascular nature of ALHE. RFA was performed on cutting and coagulation mode with an intensity of 3 U (Surgitron FFPF EMC, Ellman International, New York, USA) with prior application of topical EMLA Cream (a eutectic mixture of local anesthetics -lidocaine 2.5% and prilocaine 2.5%) for 30 minutes. The sessions were repeated on a weekly basis, with each particular papule being targeted on alternate sessions till the resolution of papules. Each lesion required 2–3 such sessions. The patient was also advised to apply topical timolol maleate (0.5%) solution twice a day on the papules to combat the deep vascular component of the disease as well as to prevent the recurrence. All papules healed without scarring and there was no recurrence on 1 year follow up [Figure 3].

Figure 1.

Multiple erythematous papules on right pinna

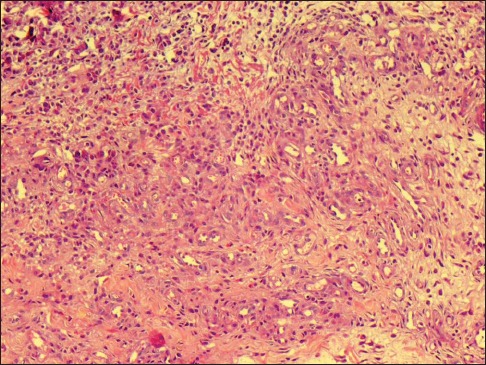

Figure 2.

(Hematoxylin and Eosin stain, ×100) Intradermal nodule of proliferating capillary channels lined by pump endothelial cells and surrounded by lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils

Figure 3.

Resolution after combination therapy of RFA and timolol

Discussion

ALHE is a benign vascular neoplasm characterized by multiple, erythematous papules and/or subcutaneous nodules predominantly on the head and neck.[1] Other sites such as the trunk, hands, legs, genitalia or oral mucosa can also be involved. It usually presents in women in the age group of 20–50 years.[1,2] The condition is generally asymptomatic but can also be present with pruritus, tenderness, pulsation and bleeding after trauma, or spontaneous.[1,2] Peripheral eosinophilia occurs in approximately 20% of patients.[1] Associated lymphadenopathy may be seen in ALHE. Serum immunoglobulin E is unremarkable.[1]

The exact etiology of ALHE is still unknown. It is considered to be a vascular malformation with reactive vascular proliferation, as evident by inflammatory infiltrate and endothelial cell proliferation. Local trauma, arteriovenous shunting, raised serum estrogen level, pregnancy and external otitis media can trigger it.[1,2] Mutation in the TEK gene, which encodes the endothelial cell tyrosine kinase receptor Tie-2, T-cell receptor gene (TCR) rearrangement, and low T cell clonity are also reported in ALHE.[1] Eosinophils may also play a role in the pathogenesis of ALHE by initiating inflammatory reaction, by increase in vascular permeability, production of nitric oxide and eosinophilic cationic protein, enhancement of leukocyte migration, and amplification of T cell response leading to reactive vascular proliferation and angiogenesis.[3] Interleukin-5 (IL-5) has been implicated in the pathogenesis as it interferes with the production, mobilization and activation of eosinophils.[3]

Differential diagnoses of ALHE include Kimura disease, pyogenic granuloma and angiokeratoma circumscriptum.[1,2] Kimura disease occurs mainly in young Asian males as asymptomatic, large deep nodules, or subcutaneous plaques, predominately on the head and neck area. Peripheral eosinophilia with raised serum immunoglobulin E is seen in this condition. Histologically, it is characterized by lymphoid proliferation with germinal center and fibrosis. Eosinophil abscess may also occur in Kimura disease.[1,2]

Various treatment modalities have been used to treat ALHE with variable response, including intralesional corticosteroids, cryosurgery, electrodessication, topical tacrolimus, interferon alfa-2a, topical imiquimod, pentoxyphilline, and isotretenoin.[2,4,5] For larger lesions, Mohs micrographic surgery is preferred over simple surgical excision as the latter is associated with recurrence. Newer lasers such as pulsed-dye, carbon dioxide, neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet, long-pulse tunable dye, and copper vapor have been used with some success.[1,2,4,5]

Recently, Bevacizumab have been found efficacious in ALHE due to decreased vascular endothelial growth factor expression leading to anti-angiogenesis.[4] Mepolizumab leads to complete symptomatic relief in ALHE by blocking the interaction between IL-5 and its receptor complex expressed on the cell surface of eosinophils.[3,4] Holster et al. have shown good response with oral propanol, which again points to the vascular nature of the disease.[4]

A combination therapy of RFA followed by sclerotherapy using 3% polidocanol was tried on 3 patients with no recurrence in 6 months to 3 years of follow up.[2] Complications of sclerotherapy include allergic reactions, cutaneous or mucosal necrosis, and sensory nerve or motor nerve injuries such as facial paralysis.[6] Intralesional RFA has also been tried for nodular ALHE.[5] However, it is a blind procedure and cannot be performed in areas where important structures such as major nerves and vessels lie in the vicinity of or within the lesion.[5]

Therefore, we chose to treat our patient with a novel combination therapy of RFA and topical timolol, which has not been described before. The superficial component of the disease was treated with RFA. RFA works on the principle of increasing the frequency and voltage while simultaneously decreasing the amperage of alternating current. The passage of ultrahigh frequency radiowaves through the tissue generates heat due to tissue resistance and causes thermal destruction of the tissue.[5] Concomitant use of timolol helped in the reduction of the vascular component of ALHE, and thus resulted in an early remission of the disease with no recurrence.

Timolol, similar to propranolol, is a nonselective beta-blocker.[7] Timolol is available in a topical solution and a gel-forming solution in concentrations of 0.25% and 0.5%.[7,8] Recent reports suggest the role of topical timolol gel for the treatment of infantile hemangiomas.[9] It was found that topical timolol was more effective for plaque than for nodular lesions and for proliferating than for involuting lesions.[9] It has been used successfully in the management of pyogenic granuloma, classic Kaposi's sarcoma, graft-versus-host disease associated angiomatosis, idiopathic pyoderma gangrenosum and recalcitrant wounds.[10,11,12,13,14]

Timolol is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for ALHE. Topical tacrolimus and timolol have been reported in the management of ALHE.[15] Resolution of ALHE by timolol may be due to beta blockade leading to vasoconstriction, inhibition of angiogenesis, and induction of apoptosis resulting in diminished erythema and size.[7,8] The major advantages of topical timolol are cost, ease of administration, wide availability and minimal risk of drug-related adverse events. The predominant adverse effects include hypotension, hypoglycemia, bronchospasm, exacerbation of asthma and local pruritus.[7,8] In our case, the drug was topically applied to the skin of patients and therefore, there was likely to be minimal absorption of the drug into the bloodstream. Hence, no adverse effects were observed. Rapid response of RFA and topical timolol combination in our case might be due to the deeper penetration of timolol in the papules and plaques after RFA. However, further reports are needed to assess the penetration of topical timolol to be efficacious in nodular or subcutaneous types of ALHE.

Conclusion

ALHE is a rare chronic disease and resistant to treatment. The combination of RFA and topical timolol offers a simple, efficacious, noninvasive and inexpensive modality of treatment for ALHE.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Guo R, Gavino AC. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:683–6. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0334-RS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khunger N, Pahwa M, Jain RK. Angiolymphoid Hyperplasia with Eosinophilia Treated with a Novel Combination Technique of Radiofrequency Ablation and Sclerotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:422–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leiferman KM, Beck LA, Gleich GJ. Regulation of the production and activation of eosinophils. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, Wolff K, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New Delhi: McGraw-Hill; 2012. pp. 351–62. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horst C, Kapur N. Propranolol: A novel treatment for angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:810–2. doi: 10.1111/ced.12412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh S, Dayal M, Walia R, Arava S, Sharma S, Gupta S. Intralesional radiofrequency ablation for nodular angiolymphoid hyperplasia on forehead: A minimally invasive approach. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:419–21. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.140300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng JW, Mai HM, Zhang L, Wang YA, Fan XD, Su LX, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of head and neck venous malformations. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2013;6:377–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Admani S, Feldstein S, Gonzalez EM, Friedlander SF. Beta blockers: An innovation in the treatment of infantile haemangioma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:37–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu L, Li S, Su B, Liu Z, Fang J, Zhu L, et al. Treatment of superficial infantile hemangiomas with timolol: Evaluation of short-term efficacy and safety in infants. Exp Ther Med. 2013;6:388–90. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah MK. Beta blockers in infantile hemangiomas: A practical guide. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2014;15:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knopfel N, Escudero-GongoraMdel M, Bauza A, Martin-Santiago A. Timolol for the treatment of pyogenic granuloma (PG) in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:e105–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alcantara-Reifs CM, Salido-Vallejo R, Garnacho-Saucedo GM, Velez Garcia-Nieto A. Classic Kaposi's sarcoma treated with topical 0.5% timolol gel. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:309–11. doi: 10.1111/dth.12381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bashline BR, Mortazie M, Schapiro B, Fivenson D. Graft-versus-host Disease-associated angiomatosis treated with topical timolol solution. Wounds. 2016;28:e18–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu DY, Fischer R, Fraga G, Aires DJ. Collagenase ointment and topical timolol gel for treating idiopathic pyodermagangrenosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:e225–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braun LR, Lamel SA, Richmond NA, Kirsner RS. Topical timolol for recalcitrant wounds. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1400–2. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.7135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chacon A, Mercer J. Successful management of angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia in a split-face trial of topical tacrolimus and timolol solution. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2016;15:436–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]