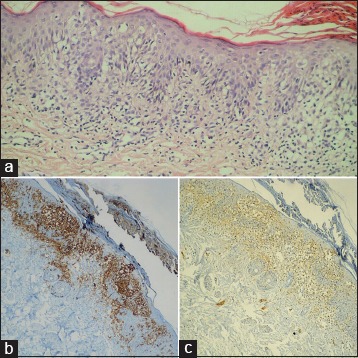

A 1-year-old girl was brought to our clinic by her parents with the complaint of papulosquamous lesions covered with hemorrhagic crusts on the anterior trunk. The patient had developed erythematous squamous plaques on the scalp, inguinal region, and the face at the age of 3 months. The patient was given a therapy of topical steroids and oral antihistaminic drugs. However, the lesions did not resolve. Dermatological examination revealed papulosquamous papules and plaques covered with hemorrhagic crusts on the scalp, skin folds, and on the anterior trunk [Figure 1]. The patient had a history of frequent otitis media. Hematological investigations indicated presence of pancytopenia. Ultrasonography showed lymphadenopathy in the cervical region. Histopathologic evaluation of the lesions on the anterior trunk showed mononuclear cell infiltration in the interstitial region in the papillary and reticular dermis and histiocytic cell infiltration in the papillary dermis [Figure 2a]. Immunohistochemical analysis indicated CD1a surface antigen (+) and S100 protein (+) [Figure 2b and c].

Figure 1.

Dermatological examination revealed papulosquamous papules and plaques covered with hemorrhagic crusts on the scalp, skin folds, and on the anterior trunk

Figure 2.

(a) Mononuclear cell infiltration in the interstitial region in the papillary and reticular dermis and histiocytic cell infiltration in the papillary dermis (H and E, ×200). (b) Immunohistochemical analysis indicated CD1a surface antigen (+) (×200). (c) Immunohistochemical analysis indicated S100 protein (+) (×200)

What Is Your Diagnosis?

Answer

Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Discussion

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare disease that involves clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells which immunophenotypically stain positive for S100, CD1a and langerin. The cytoplasmic Birbeck granules are an ultrastructural hallmark of LCH.[1] LCH may be seen at any age including neonates but it mostly affects children aged 1–3 years. Male-to-female ratio is almost 2/1. In some cases, LCH may be associated with the family history.[2] Moreover, although the exact etiology and pathogenesis of LCH remains unknown, multiple factors have been implicated, including defective immune system, infections, environmental factors, a family history of thyroid disease, and insufficient vaccination.[3] LCH becomes more diffuse as the age of the patient advances; while acute diffuse multiple-organ failure mostly occurs in children aged below 3 years, the indolent course of LCH with single organ involvement is mostly seen in older children and adults.[2,4] Our case had multifocal LCH.

Clinical findings of LCH vary according to the organs involved and the diffuseness of the disease. Although LCH is limited to a single organ such as a bone in almost 55% of the patients, it involves multiple organs in other patients. The most commonly involved organs are the bones (77%), followed by skin (39%), lymph nodes (19%), liver (16%), spleen (13%), oral mucosa (13%), and central nervous system (6%).[4,5] In most of the patients with skin involvement, LCH is characterized by brown-purple papules measuring 1–2 mm in size and distributed in the scalp, neck folds, axilla, perineum, and trunk. Moreover, pustular, purpuric, petechial, vesicular, and papulonodular lesions may also be seen. In addition, brittle nails, hyperkeratosis, paronychia, onycholysis, or permanent nail dystrophies have also been reported.[2,4,5]

Definitive diagnosis of LCH is often established by the pathologic analysis of the affected tissue. Skin biopsy of the lesions is usually recommended. Histopathologic analysis of LCH often indicates proliferation of LCH cells in the papillary dermis. Dermal LCH cells are often admixed with eosinophils, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. Immunohistochemically, LCH cells stain positive for CD1a and S100 proteins. Presence of Birbeck granules can be detected with electron microscopy.[1,6]

Treatment of LCH may not be required in all cases as isolated skin lesions may resolve spontaneously. In patients with skin-limited LCH, a therapy including topical corticosteroids, 20% topical nitrogen mustard, and photochemotherapy (PUVA) could be prescribed.[2,6] By presenting the current case, we aim to highlight the probability of rare manifestation of hemorrhagic papules and plaques in LCH with skin involvement.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Valdivieso M, Bueno C. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96:275–84. doi: 10.1016/s0001-7310(05)75054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wollina U, Langner D, Hansel G, Schönlebe J. Cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: The spectrum of a rare cutaneous neoplasia. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10354-016-0460-3. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satter EK, High WA. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: A review of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:291–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arico M, Egeler RM. Clinical aspects of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1998;12:247–59. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newman B, Hu W, Nigro K, Gilliam AC. Aggressive histiocytic disorders that can involve the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:302–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmitz L, Favara BE. Nosology and pathology of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Hematol Clin North Am. 1998;12:222–46. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]