Abstract

The inbred mouse strain BTBR T+ Itpr3tf/J (BTBR) i studied as a model of idiopathic autism because they are less social and more resistant to change than other strains. Forebrain serotonin receptors and the response to serotonin drugs are altered in BTBR mice, yet it remains unknown if serotonin neurons themselves are abnormal. In this study, we found that serotonin tissue content and the density of serotonin axons is reduced in the hippocampus of BTBR mice in comparison to C57BL/6J (C57) mice. This was accompanied by possible compensatory changes in serotonin neurons that were most pronounced in regions known to provide innervation to the hippocampus: the caudal dorsal raphe (B6) and the median raphe. These changes included increased numbers of serotonin neurons and hyperactivation of Fos expression. Metrics of serotonin neurons in the rostral 2/3 of the dorsal raphe and serotonin content of the prefrontal cortex were less impacted. Thus, serotonin neurons exhibit region-dependent abnormalities in the BTBR mouse that may contribute to their altered behavioral profile.

Keywords: dorsal raphel, median raphe, hippocampus, monoamine, norepinephrine, SERT, swim

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is an increasingly prevalent neurodevelopmental disorder associated with altered social behavior, impaired communication skills, and increased restricted and repetitive behaviors. The exact cause or causes of ASD are unknown and multiple genetic and environmental factors may be involved. Serotonin is one of several neurotransmitters that could underlie some of the behavioral impairments characteristic of ASD. Interest in serotonin originated over 50 years ago with the discovery that elevated blood serotonin levels was common in autistic patients [Schain and Freedman, 1961] (reviewed by Muller, Anacker, and Veenstra-VanderWeele [2016]). However, hyperserotonimia does not consistently correlate with any clinical feature of autism [Mulder et al., 2004], and the presence and nature of a correlative brain serotonin abnormality are still poorly understood.

Mutations in genes that influence monoamine neurotransmission appear sufficient to generate behavioral alterations relevant to ASD [Brunner, Nelen, Breakefield, Ropers, and van Oost, 1993; Piton et al., 2014]. Some evidence suggests that certain rare human variants of the serotonin transporter (SERT) gene SLC6A4 may be associated with ASD and in particular with the presence of rigid-compulsive behaviors and tactile hypersensitivity [Sutcliffe et al., 2005]. Mice bearing the rare human Ala56 SLC6A4 allele display altered behavioral performance in social and repetitive behavior, although the severity of these deficits depends on background strain [Kerr et al., 2013; Veenstra-VanderWeele et al., 2012]. Mice lacking the rate-limiting enzyme in brain serotonin synthesis, tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) 2, have deficits in measures of sociability and cognitive flexibility [Kane et al., 2012; Mosienko et al., 2015]. These observations support the possibility that serotonin could be part of a common neural basis for ASD.

BTBR T+ Itpr3tf/J (BTBR) mice may be useful tool to understand the neural circuit aberrations that underlie ASD due to their unique behavioral profile. This inbred mouse strain exhibits reduced play and social approach behavior compared to other strains [Bolivar, Walters, & Phoenix, 2007; McFarlane et al., 2008; Moy et al., 2007; Pobbe et al., 2010; Scattoni, Ricceri, & Crawley, 2011; Yang, Zhodzishsky, & Crawley, 2007]. In addition, BTBR mice have evidence of restricted-repetitive behaviors, such as excessive self-grooming and they perseverate with active coping strategy in the forced swim test [Onaivi et al., 2011; Silverman et al., 2010]. A previous study examined the potential for brain abnormalities in the serotonin system in BTBR mice and found evidence for reduced SERT, increased 5-HT1A receptor signaling capacity, and altered behavioral responses to 5-HT1A receptor ligands [Gould et al., 2011, 2014]. Serotonergic drugs including fluoxetine and the 5-HT1A partial agonist busperone enhance social interaction in these mice. In addition, risperidone and the selective 5-HT2A antagonist M100907 normalize reversal learning in BTBR mice [Amodeo, Jones, Sweeney, & Ragozzino, 2014].

While the forebrain response to serotonergic ligands and some measures of the endogenous serotonin system are altered in the BTBR mouse, it remains poorly understood if there are developmental, functional, or morphometric aberrations within serotonin neurons themselves. Identification of such abnormalities could provide clues to what could be a common serotonergic circuit deficit present in ASD when generated by different causes. In this study, we asked if serotonin neurons themselves are different in BTBR mice or if deficits are restricted to the forebrain response to serotonin.

Methods and Materials

Mice

Procedures using animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Boston Children’s Hospital. Breeding pairs of BTBR and C57BL/6J (C57) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (stock numbers 002282 and 000664, respectively). Progeny born at Boston Children’s Hospital were used as study subjects at postnatal day 28 (±1 day). Since autism is a disorder that manifests in childhood, we reasoned that this younger age is at least equally relevant to understanding the neural mechanisms of the disorder as older ages, if not more relevant. Postnatal day 28 is thought to represent an early adolescent state in rodent development [Laviola, Macri, Morley-Fletcher, & Adriani, 2003] and major postnatal developmental changes of the serotonin system have largely been completed by this age [Lidov and Molliver, 1982; Liu and Wong-Riley, 2010], although there are likely further refinements of the system into adulthood. For High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), there were ten individuals per group. For serotonin neuron number estimates, there were six individuals per group (a subset of the animals used for swim and Fos analysis). For serotonin axon terminal analysis, there were eight individuals per group (a subset of the animals used for swim and Fos). For swim behavior and Fos analyses, there were 16–19 individuals per group. Swim behavior and Fos were analyzed first to determine if there was an effect of sex. Males and females, however, had similar behavioral performance and Fos expression (no significant main effect of sex or sex × strain interaction in an ANOVA). Therefore, the remaining analyses were sex balanced, but were underpowered for further analysis of sex effects (i.e., for HPLC four to six of each group were male).

HPLC Analysis

To measure the content of monoamines and their metabolites, whole brains were rapidly extracted and snap-frozen in isopentane cooled with dry ice (n = 10 per genotype). The prefrontal cortex, dorsal striatum (both medial and lateral), dorsal hippocampus (primarily the dentate gyrus and CA1 subfields), and dorsal raphe (DR) were punched out of serial 300-μm slices cut on a cryostat with a 2 mm diameter punch and analyzed by the Neurochemistry Core Facility at Vanderbilt University. These forebrain areas were selected because they represent termination fields with distinct areas of origin within the raphe nuclei, they were implicated as areas where serotonin neurotransmission may be compromised in BTBR mice, and they could be sampled reproducibly from animal to animal [Amodeo, Jones, Sweeney, & Ragozzino, 2012; Commons, in press; Gould et al., 2011]. For the HPLC, frozen brain tissue samples were homogenized by using a tissue dismembrator (Misonix XL-2000; Qsonica) in a solution containing 100 mM TCA, 10 mM NaC2H3O2, 100 μM EDTA, 5 ng/mL isoproterenol (an internal standard), and 7.5% (vol/vol) methanol (pH 3.8). Using a Waters 2707 autosampler, 10 μL of supernatant from each sample was injected onto a Phenomenex Kintex (2.6 μm, 100 A) C18 HPLC column (100 × 4.6 mm). Biogenic amines were eluted with a mobile phase [100 mM TCA, 10 mM NaC2H3O2, 100 μM EDTA, and 7.5% methanol (pH 3.8)] delivered at 0.6 mL/min by using a Waters 515 HPLC pump. Analytes were detected by using an Antec Decade II (oxidation: 0.4) electrochemical detector operated at 33 °C. Empower software was used to manage HPLC instrument control and data acquisition. Data were analyzed using ANOVA with factors for region, neurochemical, and strain.

Tissue from the same individuals was used for three analyses using immunofluorescence: quantification of serotonin axon density, serotonin neuron number, and Fos expression within serotonin neurons. Since serotonin neurons tend to have very low levels of Fos expression in naïve conditions, these mice were exposed to an acute stress, swim, prior to collecting their brans. Swim is known to activate serotonin neurons and modify serotonin release in the forebrain, which influences the behavior exhibited; thus, it is a stimulus well characterized with respect to serotonin involvement [Cryan, Valentino, & Lucki, 2005]. In addition, autism is associated with poor response to stress and difficulty adapting to change [Spratt et al., 2012] suggesting that the swim test may be a relevant behavioral challenge in autism models. The acute swim was not expected to have an effect on other endpoints (serotonin axon terminal ramification pattern or serotonin neuron number). As Fos was not compared under naïve conditions, there is no assumption that differences between strains would be necessarily contigent on the swim. However, this experimental design resulted in the potential to score swim behavior.

For the swim, mice were placed in a cylindrical glass tank (46 cm high × 20 cm diameter) filled with water (25 ± 1 °C) to a depth of 30 cm for 15 min and swim behavior video-recorded for subsequent behavioral scoring. Mice were perfused 120 min after the start of the acute stress event to allow for the expression and accumulation of the Fos protein. Swim behavior was scored as active (defined by lateral movement from quadrant to quadrant) or inactive (defined by minimal movement) coping every 5 sec throughout the swim test. Immediately after the test, the mice were removed from the tank, dried off, and returned to their home cage.

Mice were perfused transcardially through the ascending aorta with 30 mL 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (4 °C, pH 7.4) after they were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg). Brains were removed and stored in the same fixative solution for 48 hr and then equilibrated in a solution of 30% sucrose plus sodium azide in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. Brains were frozen and coronally sectioned at 40 μM thickness. Sections were processed while floating.

SERT Axon Density Analysis

Immunofluorescence detection of SERT was used to quantify serotonin axon terminal ramification pattern. While some nonserotonin neurons express SERT earlier in development [Gaspar, Cases, and Maroteaux, 2003], after the third week of life, immunolabeling for SERT detects serotonin neuron axons with high sensitivity and specificity [Boylan, Bennett-Clarke, Chiaia, & Rhoades, 2000; Nielsen, Brask, Knudsen, & Aznar, 2006]. To account for potential technical variation in immunofluorescence detection efficiency with different experimental days, tissue from individuals of each genotype were processed side-by-side and analyzed in a matched pair design. Sections were incubated in primary antisera raised in rabbit (SERT, Calbiochem, catalog PC177L) diluted 1:1000 in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 0.3% Triton X-100, and 0.01% sodium azide (PBS-BSA-T-A) at 4 °C for 2–3 days. All immunoreactivity was detected using fluorescent secondary antisera raised in donkey and diluted in PBS-BSA-T-A at room temperature for 90 min.

Images of tissue from each pair of individuals processed together were photographed at the same exposure times and displayed with equivalent saturation curves. Using NIHs Image J software, an equivalent threshold was applied to matched pair images to define axons, and the number of objects defined was measured using Analyze-Measure. Four sections were sampled per individual mouse, and results were averaged to generate a mean density of labeled objects per individual. Values between eight sets of pairs were compared using a paired t-test. A paired t-test was consistent with our matched pair design, which was used to control for variability in immunofluorescence between technical runs.

Serotonin Neuron Number Estimates

To estimate the number of serotonin neurons, sections throughout the raphe were photographed to detect immunolabeling for TPH (Millipore, AB1541 raised in sheep) and a nuclear stain 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) applied in the coverslipping medium (Molecular Probes). Immunolabeling for TPH was completed in a similar fashion to SERT. The raphe nuclei were systematically sampled by analyzing every third section where they were present. Sections were photographed using an Olympus fluorescence microscope with a 10 × objective, a Hamamatsu Orca ER camera, and SlideBook computer software. Three rostrocaudal divisions of the DR were made: rostral was −4.16 to −4.24 mm, middle was −4.36 to −4.84 mm, and caudal was −4.96 to −5.20 mm relative to Bregma. These three divisions were divided in half into dorsal and ventral subregions. The lateral wing of the middle DR was pooled with the dorsal middle DR subregion to the extent to which they appeared in the same images. Images of the median raphe (MR) were sampled in sections that also contained the middle DR.

Using NIH Image J Software, images containing DAPI labeling for nuclei and TPH labeling for serotonin neurons were analyzed. Images were split into separate color channels. For each channel, the background was subtracted and a threshold was applied to define labeled areas. A selection area generated by the area immunolabeled for TPH was applied to the cognate image of DAPI-defined nuclei. The DAPI-defined nuclei within the TPH selection area were counted using Analyze-Measure command. The mean number of DAPI cells per section per region was determined for each mouse strain. Group means and standard error of the means were calculated for each region and analyzed for significant effect of mouse strain using ANOVA. Posthoc comparisons between the two genotypes were completed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test with alpha set at P < 0.05. In areas where a positive result was found, the size of TPH neurons was analyzed by measuring the area of an oval that best fit over the cell body to determine if differences between groups could have been related to differences in the sizes of neurons (larger neurons would be sampled more often, generating the appearance of more neurons). For this analysis, measures were averaged from eight arbitrarily selected neurons/mouse and nine mice were sampled in each group.

Fos immunoreactivity was detected by incubating sections in rabbit anti-Fos sera (EMD Chemicals, PC38) diluted 1:10,000. 5-HT neurons were detected using an antiserum raised against TPH diluted 1:1,000 raised in sheep (Millipore, AB1541). Secondary antisera raised in donkey with minimal cross reactivity to other species and were conjugated to CY3 or Alexa-488 diluted 1:100 were used to detect immunolabeling.

To quantify Fos labeling, individual mice were coded to conduct the analysis blind to the mouse strain. Within each subregion sampled as described for serotonin neuron number estimates, TPH cells with Fos expression were manually enumerated by visualizing each channel independently and together. Every third section through the DR was processed such that two to three sections were sampled for each subregion/mouse. The number of dually immunolabeled cells was normalized per section for each subregion for each individual mouse within a group. Then, by averaging numbers across mice, group means and standard error of the means were calculated for each subregion. An ANOVA was used to determine if there was a significant effect of strain and subregion. Posthoc determination of differences between the two strains was completed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test (alpha set at P < 0.05).

Results

HPLC

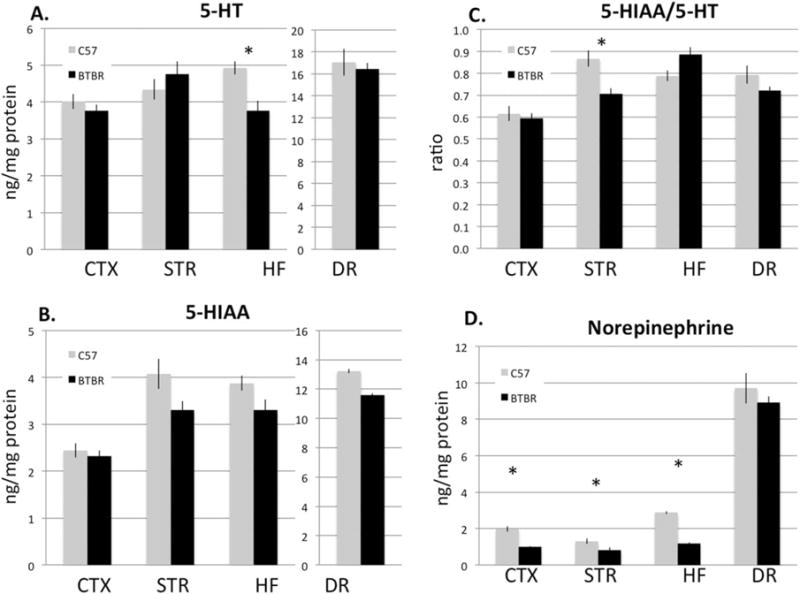

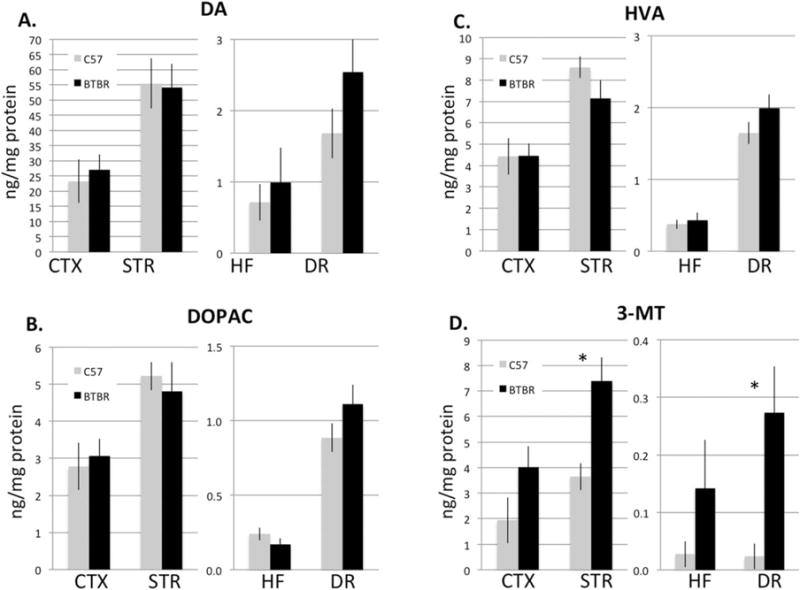

Monoamine content of prefrontal cortex, dorsal striatum, dorsal hippocampus, and DR were assayed. Serotonin levels were significantly reduced in the hippocampus (about a 24% decrease P = 0.004), but undistinguishable from C57 in frontal cortex, striatum, and DR (Fig. 1). The major serotonin metabolite, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), trended lower but nonsignificantly so (P = 0.564, 0.065, 0.076, and 0.142 in cortex, striatum, hippocampus and DR, respectively). The ratio of 5-HT to its metabolite was significantly reduced only in the striatum (P = 0.006), as a consequence of both slightly higher absolute serotonin and lower 5-HIAA levels. In addition, in BTBR, norepinephrine (NE) was found significantly reduced in the cortex, striatum, and hippocampus (Fig. 1) (P = 3 × 10−5, 0.04, and 3 × 10−10, respectively). However, in all regions, there was no significant effect of strain on dopamine or any of its metabolites except for 3-methoxytyramine (3-MT) (Fig. 2). 3-MT was elevated significantly in the striatum and DR (P = 0.005 and 0.01, respectively) and nonsignificantly elevated in the hippocampus. While changes in 3-MT might suggest altered function of catechol-o-methyltransferase or monoamine oxidase, other products of these enzymes (homovanillic acid (HVA) and 5-HIAA, respectively) did not show similar changes.

Figure 1.

HPLC analysis of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT), the serotonin metabolite 5-HIAA, their ratio, and NE in frontal cortex, dorsal striatum (STR), the hippocampal formation (HF), and the dorsal raphe (DR) in C57 (grey) and BTBR (black) mice. (A) BTBR mice have significantly less serotonin in the HF p = 0.004, (B) nonsignificant trends for lower 5-HIAA in several regions, and (C) a reduced ratio of metabolite to transmitter in the striatum (P = 0.006). (D) In addition, BTBR mice have significantly reduced NE content in all the forebrain areas examined (P = 3 × 10−5, 0.04, and 3 × 10−10, respectively). N = 10 per group.

Figure 2.

(A) Dopamine (DA) and its metabolites, (B) 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid and (C) HVA were not significantly different between C57 (grey) and BTBR mice (black) in any area. (D) However, in BTBR mice, there was significantly greater 3-metholxytyramine (3-MT) both in the STR and DR (P = 0.005 and 0.01, respectively). N = 10 per group.

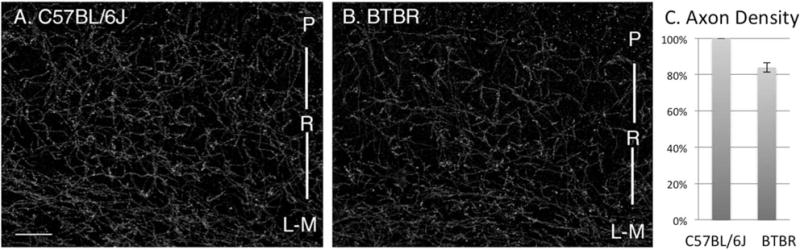

To investigate if there were also changes in serotonin axon ramification in the hippocampus, we analyzed the density of axons immunolabeled for SERT in the CA1 subfield (Fig. 3). Immunofluorescent labeling of SERT axons revealed about a 16% reduction (P = 0.0007) in the density of innervation to the hippocampus compared to C57 mice, suggesting at least in part the reduction of serotonin may be caused by fewer axons overall. The possibility that there may also be less serotonin and/or SERT per individual axon was not ruled out.

Figure 3.

Comparison of axons containing the serotonin reuptake transporter (SERT) in C57 (A) and BTBR (B) mice. Images are of comparable fields in the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus including strata pyramidale (P) radiatum (R) and lacunosum-moleculare (L-M). (C) SERT axon density in BTBR mice is about 16% less than in pair-matched controls, (P = 0.0007) N = 8 per group. Bar = 150 μm.

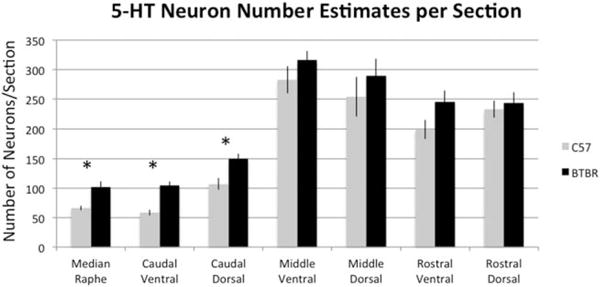

To evaluate serotonin neurons themselves, we estimated serotonin neuron number in six subregions of the DR and MR. This analysis showed that the caudal ventral region and caudal dorsal region indicated on the Paxinos atlas as “interfasicular DR” and “DR caudal” both of which are also called “B6,” contained more serotonin neurons in BTBR compared to C57 (Figs. 4 and 5) (P = 0.0003 for caudal ventral and P = 0.01 for caudal dorsal). In addition, estimates of serotonin neurons in the MR were found elevated in BTBR mice (P = 0.01). Meanwhile, serotonin neuron number trended higher in the remaining areas of the DR but was not significantly different from C57 mice. Serotonin neuron size was measured in B6 to confirm that the change in measured density more likely reflected increased neuron number, rather than larger neurons that could be sampled more frequently. This analysis showed that the average size of cell bodies in this region was equivalent to that in C57 mice (cell body area for C57 was 1211 μm2 ± 87 (S.E.M.) vs. 1224 μm2 ± 69 (S.E.M.) for BTBR, P = 0.87).

Figure 4.

Per section estimates of serotonin (5-HT) neurons identified by immunolabeling for TPH showed BTBR mice have an increased number of neurons in the MR (P = 0.01) and caudal third of the DR, both ventrally and dorsally in the areas also known as B6 (P = 0.0003 for caudal ventral and p = 0.01 for caudal dorsal). N = 6 per group.

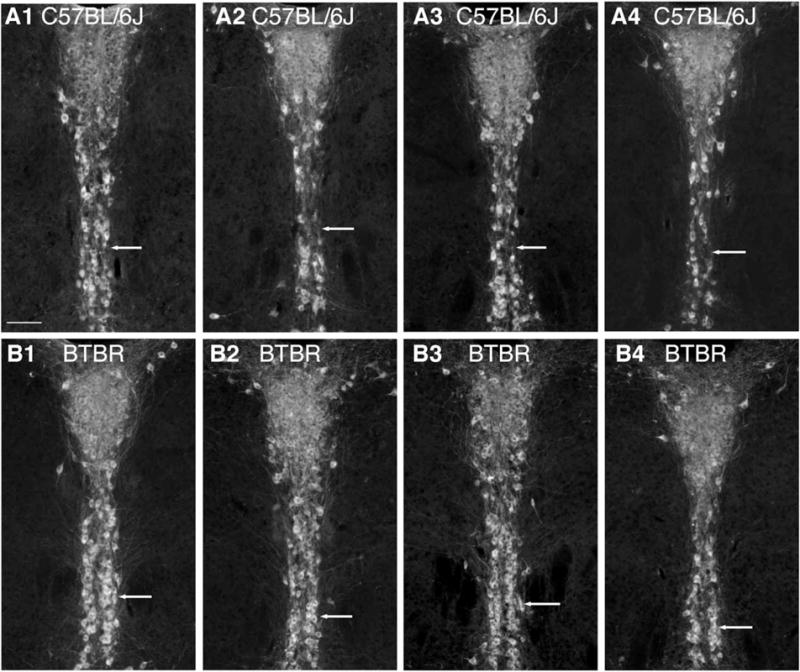

Figure 5.

Comparison of the morphology of B6 in C57 and BTBR. A1-4 shows the same level from four different C57 mice and matched below (B1-4) are comparable images from 4 BTBR mice. Ventrally, the difference in cell number can be detected visually in that C57 mice have regions where neurons are sparse (A row, arrows) whereas in BTBR two paramedial columns of 5-HT neurons (identified by immunolabeling for TPH) are consistently visible (B row, arrows). Bar = 100 μm.

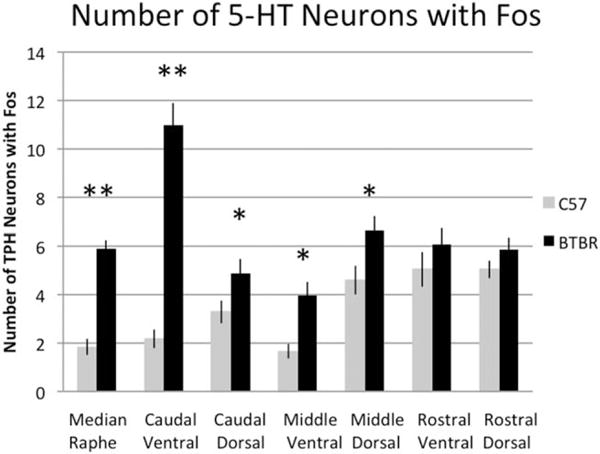

To evaluate if serotonin neurons showed differential activity state in BTBR mice compared to C57, we exposed mice of each genotype to an acute stress, swim, since this stimulus is known to increase the level of activation of the serotonin system. Subsequently, Fos expression specifically within serotonin neurons was measured (Figs. 6 and 7). Consistent with previous observations, we observed that BTBR mice exhibited excessive active coping in the swim compared to C57 [Onaivi et al., 2011; Silverman et al., 2010]. Specifically, over 15 min, the active coping scores (the number of 5-sec epochs rated as active) of BTBR averaged 154 ± 7 (S.E.M.) versus. 103 ± 8 (S.E.M.) for C57 (P = 0.0001). Analysis of Fos showed that BTBR mice had excessive expression particularly within the same regions that had more serotonin neurons overall including the ventral caudal region of the DR (P = 3 × 10−7), dorsal caudal (P = 0.02), and in the MR (P = 1 × 10−5). In the area with the greatest magnitude differences (ventral caudal DR), there was less than a twofold increase in estimates of serotonin neuron number while the increase in Fos was fourfold; suggesting that the increased Fos was both a consequence of the presence of more neurons combined with higher activity state. Significantly higher Fos was also detected in the ventral middle (P = 0.002) area.

Figure 6.

Measured after swim, BTBR mice have significantly more 5-HT neurons with activated expression of Fos. The largest magnitude and most statistically significant effects occurring in the MR and caudal ventral part of the DR. 5-HT neurons here identified by immunolabeling for TPH. **P < 0.0005. Significant increases are also detected caudal dorsal and in middle levels both dorsal and ventral (*P < 0.05). N = 16–19 per group.

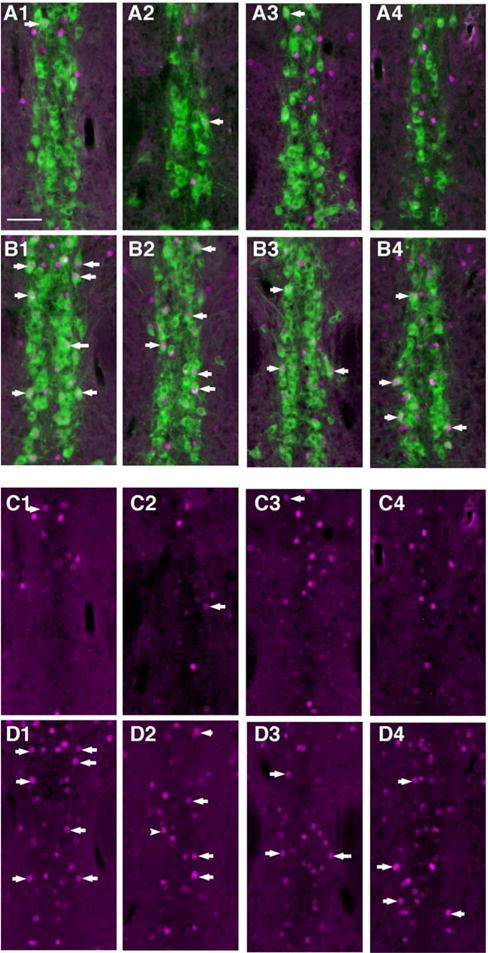

Figure 7.

Example images of the caudal ventral DR showing BTBR mice had more 5-HT neurons with Fos-immunolabeled nuclei. Same sections as in Figure 5. (A1-4) Same level for four different C57 mice showing 5-HT neurons (green; identified by immunolabeling for TPH) and Fos (magenta) immunolabeling together. (B1-4) Comparable images from four different BTBR mice. (C1-4) Same images as in A1-4 showing Fos-immunolabeling alone, arrows point to examples of positive Fos immunolabeling within the nucleus a serotonin neuron. (D1-4) Same images as in B1-4 showing Fos only. Some of the dually labeled neurons are indicated with arrows, and these are much more prevalent in BTBR then in C57 (quantification in Fig. 6). All panels same scale; bar in A1 = 100 μm.

Discussion

This study extends the findings showing altered forebrain expression of serotonin receptors and response to serotonin ligands [Gould et al., 2011] by providing evidence that BTBR mice have altered serotonin tissue content, axon, and cell body organization, as well as altered activity as measured by Fos expression. Thus, by multiple measures, the endogenous serotonin system in BTBR mice is distinct from C57 mice. Given the potential of serotonin neurotransmission to influence autism-related phenotypic measures, these differences could contribute to altered behavior in this mouse line.

There were increases in the estimates of serotonin neuron number and Fos expression in BTBR mice, particularly in the caudal pole of the DR (B6) as well as in the MR. Previous studies have provided evidence that B6 and MR serotonin neurons may be disturbed in autism models and further that these could contribute to an autism-relevant phenotype. Specifically, another gene associated with autism, Met, is highly expressed in B6 and MR neurons in the adult [Okaty et al., 2015; Wu and Levitt, 2013]. Conditional knockout of Met within these serotonin neurons results in sociability deficits [Okaty et al., 2015]. Models of autism produced by embryonic exposure to valproic acid (VPA) and thalidomide result in an increase in number of serotonin neurons in B6 [Narita et al., 2002] while maternal viral exposure results in increased number of serotonin neurons in the entire rostral raphe [Ohkawara, Katsuyama, Ida-Eto, Narita, & Narita, 2015]. These observations converge to raise the possibility that altered function of B6 and MR serotonin neurons may be a common feature of mouse models of autism when generated by (at least this subset) diverse causes.

The B6 region and MR share some features of connectivity and developmental origin (reviewed by Commons [in press]). One target of both these regions is the hippocampus, where serotonin abnormalities were evident in BTBR mice. However, in contrast to the increases in serotonin metrics in B6 and MR, the hippocampus had decreased serotonin content and a trend for altered ratio between serotonin and its metabolite. In addition, there was reduced density of SERT-containing axons. The opposing valence of changes in cell bodies versus terminal fields raises the possibility that they could be compensatory. A reduction in hippocampal serotonin coupled with increased serotonin neuron number is also shared with the VPA and maternal-viral infection models of autism [Dufour-Rainfray et al., 2010; Ohkawara et al., 2015]. Regardless of the origin, the current results confirm and extend the reports of reduced SERT binding in the hippocampus as measured by autoradiography [Gould et al., 2011] and indicate a reduction in axon density contributes to this observation and that both are associated with an overall reduction in serotonin content in BTBR mice.

Several other hippocampal abnormalities have been reported in the BTBR mouse including: age-dependent changes in 5-HT1A receptors [Gould et al., 2014], severely reduced hippocampal commissure [Wahlsten, Metten, & Crabbe, 2003], reduced hippocampal neurogenesis, reduced hippocampal BDNF expression [Stephenson et al., 2011] several altered features of synaptic plasticity [MacPherson, McGaffigan, Wahlsten, & Nguyen, 2008; Seese, Maske, Lynch, & Gall, 2014; Scattoni, Martire, Cartocci, Ferrante, & Ricceri, 2013], and marked transcriptional changes [Daimon et al., 2015]. In fact, the reduction of BDNF could be a causal factor for the loss of serotonin innervation: BDNF is a known trophic factor for serotonin axons and reduction in BDNF expression is associated with loss of hippocampal serotonin innervation [Lyons et al., 1999; Mamounas et al., 2000]. Serotonin feeds back to regulate BDNF expression, likely through 5-HT2C receptors [Hill et al., 2011; Migliarini, Pacini, Pelosi, Lunardi, & Pasqualetti, 2013] although the status of this receptor has not been investigated yet in BTBR mice.

BTBR mice showed altered behavioral coping strategies when faced with an acute stress, swim, replicating previous reports [Onaivi et al., 2011; Silverman et al., 2010]. The swim test is known to change the activity state of serotonin neurons [Commons, 2008] producing region-dependent changes in serotonin release in the forebrain [Kirby and Lucki, 1997] and there is an extensive literature on serotonin pharmacology in swim (reviewed by Cryan et al. [2005]) making the swim test a relevant approach to gain insight into the serotonin system. Interpretation of this behavioral performance with respect to depression in mouse models of autism is not trivial however. In humans, the diagnosis of depression in autism can be complicated and its prevalence is not agreed upon (reviewed by Chandrasekhar and Sikich [2015]). In rodents, the factors (emotional, motivational, and cognitive) that drive coping strategies under stress are unknown and they could be complex. Other behavioral features present in autism, and indeed present in BTBR mice, could be expected to influence stress-coping strategy however including hyperactivity and restricted/repetitive behaviors. Thus, it is possible that perseveration with an active coping strategy in the context of a stress shown by BTBR mice could be just as likely related to behavioral rigidity as to altered mood.

The triumvirate of altered swim strategy, changes in the hippocampus, and effects on serotonin neurons overlap in their association to stress biology, and indeed there is known dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in BTBR mice. BTBR mice have elevated baseline serum coticosterone levels and enhanced increases in response to stress [Benno, Smirnova, Vera, Liggett, & Schanz, 2009; Frye and Llaneza, 2010; Gould et al., 2014; Silverman et al., 2010]. Serotonin signaling in the hippocampus contributes to feedback regulation of the HPA axis exerted by that structure [Lanfumey Mongeau, Cohen-Salmon, & Hamon, 2008; Pompili et al., 2010]. In the rat, both inescapable shock and swim stress activates Fos expression in B6 serotonin neurons suggesting the involvement of this area in stress coping [Commons, 2008; Grahn et al., 1999]. However, it does not appear to be the case that the BTBR mice are simply stress-sensitive because they exhibit fairly normal responses to sensory stimuli [Silverman et al., 2010]. Their response also depends on the particular situation, for example, they appear less stressed in the Transfer of Emotional Information test, but more stressed in the Social Proximity test [Meyza et al., 2015]. Thus, the altered stress response in BTBR may be a complex mix of deficits and compensatory responses. This could be an interesting avenue to pursue in animal models of autism because HPA axis regulation may be altered in the human condition [Taylor and Corbett, 2014].

It is important to point out however that serotonin axon abnormalities are probably not restricted to the hippocampal system in BTBR mice. The striatum (in the mouse innervated by serotonin neurons in B9 [Muzerelle, Scotto-Lomassese, Bernard, Soiza-Reilly, & Gaspar, 2016]) showed significant differences in the ratio of serotonin to its metabolite suggesting region-dependent changes. Previously, others have reported higher levels of extracellular 5-HT in the striatum of BTBR mice compared to C57 after methamphetamine and MDMA, although they were equivalent under naïve conditions [Onaivi et al., 2011]. In addition, previously reported SERT reductions were noted in several different brain areas, although the hippocampus was most severely affected [Gould et al., 2011]. Other areas innervated by neurons in B6 and the MR such as the subventricular zone and lining of the ventricular walls, the suprachiasmatic nucleus, and periventricular nucleus of the thalamus (reviewed by Commons [in press]) could be impacted as well.

In addition to changes in serotonin, HPLC analysis revealed largely normal dopamine and dopamine metabolites, except for 3-MT. However, dopamine abnormalities including blunted behavioral response to the dopamine reuptake inhibitor GBR 12909 and reduced dopamine D2 receptor function have been reported in BTBR mice in comparison to C57 [Squillace et al., 2014]. More striking were consistent reductions in NE levels in the forebrain of BTBR mice. While beyond the scope of this study, alterations in NE neurotransmission may be an interesting complimentary line of investigation and add to the unique characteristics of BTBR mice. This observation would be consistent with poor attentional performance in these mice [Stapley, Guariglia, & Chadman, 2013]. Furthermore, a deficit in NE is consistent with the report that contextual fear conditioning in BTBR mice is improved by a NE reuptake inhibitor, which would be expected to abrogate a paucity of extracellular NE in the BTBR mice [Stapley et al., 2013]. In this feature, BTBR mice resemble the Engrailed-2 knock-out (EN2KO) mice, another model of autism, that likewise have deficits in NE in some fore-brain areas (frontal cortex and hippocampus), as well as deficits in fear conditioning that are restored by a NE reuptake inhibitor [Brielmaier et al., 2014]. However, EN2KO and BTBR differ in several other respects including regional patterns of monoamine alterations and behavioral performance in the swim [Brielmaier et al., 2014; Genestine et al., 2015].

Conclusion

This study finds evidence for alterations intrinsic to serotonin neurons in BTBR mice, an inbred strain with behavioral deficits relevant to ASD. Some of these changes are similar to those that occur in other animal models of ASD, which suggest dysfunction of specific subset of serotonin circuits could be common to a subset of ASD cases. Specifically, neuronal function of the caudal pole of the DR (B6) and the MR as well as their targets including the hippocampus may be of interest.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the technical assistance of Mr. Chris Panzini and Ms. Alyna Silberstein and thoughtful comments on the manuscript provided by Drs. Daniel Ehlinger and Jessica Babb (Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School). Thanks to Drs. Benlian Gao and Ginger Milne at the Neurochemistry Core at Vanderbilt University for HPLC analysis. Funding provided by the National Institutes of Health grants DA021801 and HD036379, the Brain and Behavior Foundation NARSAD Independent Investigator Award, and the Sara Page Mayo Foundation for Pediatric Pain Research.

Footnotes

The neurotransmitter serotonin has been implicated in Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs). Yet, little is known about exactly how serotonin neurons in the brain might go wrong to contribute to ASD behavior. To understand this better, we studied a particular breed of mouse that is less social than most other mice and also exhibits some repetitive behavior. We measured the amount of serotonin in the mouse’s brain and found lower levels in the hippocampus. Perhaps as a compensatory change, there was an increase in the number of serotonin neurons located in the area that projects to the hippocampus. While the hippocampus is best known for its key function in forming memories, it also plays an important role in regulating the response to stress. Therefore, our results raise the possibility that the specific serotonin circuit that influences hippocampal function could be dysfunctional in ASD. The results could support studies in humans to see if similar serotonin circuits could be abnormal, and they could justify studies to examine if manipulating these circuits to be helpful for treatment.

References

- Amodeo DA, Jones JH, Sweeney JA, Ragozzino ME. Differences in BTBR T+tf/J and C57BL/6J mice on probabilistic reversal learning and stereotyped behaviors. Behavioural Brain Research. 2012;227:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amodeo DA, Jones JH, Sweeney JA, Ragozzino ME. Risperidone and the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist M100907 improve probabilistic reversal learning in BTBR T + tf/J mice. Autism Research. 2014;7:555–567. doi: 10.1002/aur.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benno R, Smirnova Y, Vera S, Liggett A, Schanz N. Exaggerated responses to stress in the BTBR T+tf/J mouse: An unusual behavioral phenotype. Behavioural Brain Research. 2009;197:462–465. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolivar VJ, Walters SR, Phoenix JL. Assessing autism-like behavior in mice: Variations in social interactions among inbred strains. Behavioural Brain Research. 2007;176:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boylan CB, Bennett-Clarke CA, Chiaia NL, Rhoades RW. Time course of expression and function of the serotonin transporter in the neonatal rat’s primary somatosensory cortex. Somatosensory and Motor Research. 2000;17:52–60. doi: 10.1080/08990220070292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brielmaier J, Senerth JM, Silverman JL, Matteson PG, Millonig JH, DiCicco-Bloom E, Crawley JN. Chronic desipramine treatment rescues depression-related, social and cognitive deficits in Engrailed-2 knockout mice. Genes, Brain, and Behavior. 2014;13:286–298. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner HG, Nelen M, Breakefield XO, Ropers HH, van Oost BA. Abnormal behavior associated with a point mutation in the structural gene for monoamine oxidase A. Science. 1993;262:578–580. doi: 10.1126/science.8211186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar T, Sikich L. Challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of depression in autism spectrum disorders across the lifespan. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2015;17:219–227. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.2/tchandrasekhar. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commons KG. Evidence for topographically organized endogenous 5-HT-1A receptor-dependent feedback inhibition of the ascending serotonin system. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;27:2611–2618. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commons KG. Ascending serotonin neuron diversity under two umbrellas. Brain Structure and Function. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00429-015-1176-7. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan JF, Valentino RJ, Lucki I. Assessing substrates underlying the behavioral effects of antidepressants using the modified rat forced swimming test. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2005;29:547–569. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daimon CM, Jasien JM, Wood WH, 3rd, Zhang Y, Becker KG, Silverman JL, Maudsley S. Hippocampal transcriptomic and proteomic alterations in the BTBR mouse model of Autism spectrum disorder. Frontires in Physiology. 2015;6:324. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour-Rainfray D, Vourc’h P, Le Guisquet AM, Garreau L, Ternant D, Bodard S, Guilloteau D. Behavior and serotonergic disorders in rats exposed prenatally to valproate: A model for autism. Neuroscience Letters. 2010;470:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Llaneza DC. Corticosteroid and neurosteroid dysregulation in an animal model of autism, BTBR mice. Physiology and Behavior. 2010;100:264–267. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar P, Cases O, Maroteaux L. The developmental role of serotonin: News from mouse molecular genetics. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2003;4:1002–1012. doi: 10.1038/nrn1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genestine M, Lin L, Durens M, Yan Y, Jiang Y, Prem S, DiCicco-Bloom E. Engrailed-2 (En2) deletion produces multiple neurodevelopmental defects in monoamine systems, forebrain structures and neurogenesis and behavior. Human Molecular Genetics. 2015;24:5805–5827. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould GG, Burke TF, Osorio MD, Smolik CM, Zhang WQ, Onaivi ES, Hensler JG. Enhanced novelty-induced corticosterone spike and upregulated serotonin 5-HT1A and cannabinoid CB1 receptors in adolescent BTBR mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;39:158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould GG, Hensler JG, Burke TF, Benno RH, Onaivi ES, Daws LC. Density and function of central serotonin (5-HT) transporters, 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors, and effects of their targeting on BTBR T+tf/J mouse social behavior. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2011;116:291–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07104.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahn RE, Will MJ, Hammack SE, Maswood S, McQueen MB, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Activation of serotonin-immunoreactive cells in the dorsal raphe nucleus in rats exposed to an uncontrollable stressor. Brain Research. 1999;826:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RA, Murray SS, Halley PG, Binder MD, Martin SJ, van den Buuse M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression is increased in the hippocampus of 5-HT(2C) receptor knockout mice. Hippocampus. 2011;21:434–445. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane MJ, Angoa-Perez M, Briggs DI, Sykes CE, Francescutti DM, Rosenberg DR, Kuhn DM. Mice genetically depleted of brain serotonin display social impairments, communication deficits and repetitive behaviors: Possible relevance to autism. PloS one. 2012;7:e48975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr TM, Muller CL, Miah M, Jetter CS, Pfeiffer R, Shah C, Veenstra-Vanderweele J. Genetic background modulates phenotypes of serotonin transporter Ala56 knock-in mice. Molecular Autism. 2013;4:35. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-4-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby LG, Lucki I. Interaction between the forced swimming test and fluoxetine treatment on extracellular 5-hydroxytryptamine and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid in the rat. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeuticsm. 1997;282:967–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfumey L, Mongeau R, Cohen-Salmon C, Hamon M. Corticosteroid-serotonin interactions in the neuro-biological mechanisms of stress-related disorders. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32:174–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviola G, Macri S, Morley-Fletcher S, Adriani W. Risk-taking behavior in adolescent mice: Psychobiological determinants and early epigenetic influence. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2003;27:19–31. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidov HG, Molliver ME. Immunohistochemical study of the development of serotonergic neurons in the rat CNS. Brain Research Bulletin. 1982;9:559–604. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(82)90164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MT. Postnatal changes in the expressions of serotonin 1A, 1B, and 2A receptors in ten brain stem nuclei of the rat: Implication for a sensitive period. Neuroscience. 2010;165:61–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons WE, Mamounas LA, Ricaurte GA, Coppola V, Reid SW, Bora SH, Tessarollo L. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-deficient mice develop aggressiveness and hyperphagia in conjunction with brain serotonergic abnormalities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:15239–15244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson P, McGaffigan R, Wahlsten D, Nguyen PV. Impaired fear memory, altered object memory and modified hippocampal synaptic plasticity in split-brain mice. Brain Research. 2008;1210:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamounas LA, Altar CA, Blue ME, Kaplan DR, Tessarollo L, Lyons WE. BDNF promotes the regenerative sprouting, but not survival, of injured serotonergic axons in the adult rat brain. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:771–782. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00771.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane HG, Kusek GK, Yang M, Phoenix JL, Bolivar VJ, Crawley JN. Autism-like behavioral phenotypes in BTBR T+tf/J mice. Genes, Brain, and Behavior. 2008;7:152–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyza K, Nikolaev T, Kondrakiewicz K, Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ, Knapska E. Neuronal correlates of asocial behavior in a BTBR T (+) Itpr3(tf)/J mouse model of autism. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2015;9:199. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliarini S, Pacini G, Pelosi B, Lunardi G, Pasqualetti M. Lack of brain serotonin affects postnatal development and serotonergic neuronal circuitry formation. Molecular Psychiatry. 2013;18:1106–1118. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosienko V, Beis D, Pasqualetti M, Waider J, Matthes S, Qadri F, Alenina N. Life without brain serotonin: Reevaluation of serotonin function with mice deficient in brain serotonin synthesis. Behavioural Brain Research. 2015;277:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Young NB, Perez A, Holloway LP, Barbaro RP, Crawley JN. Mouse behavioral tasks relevant to autism: Phenotypes of 10 inbred strains. Behavioural Brain Research. 2007;176:4–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder EJ, Anderson GM, Kema IP, de Bildt A, van Lang ND, den Boer JA, Minderaa RB. Platelet serotonin levels in pervasive developmental disorders and mental retardation: Diagnostic group differences, within-group distribution, and behavioral correlates. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:491–499. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller CL, Anacker AM, Veenstra-VanderWeele J. The serotonin system in autism spectrum disorder: From biomarker to animal models. Neuroscience. 2016;321:24–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzerelle A, Scotto-Lomassese S, Bernard JF, Soiza-Reilly M, Gaspar P. Conditional anterograde tracing reveals distinct targeting of individual serotonin cell groups (B5-B9) to the forebrain and brainstem. Brain Structure and Function. 2016;221:535–561. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0924-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita N, Kato M, Tazoe M, Miyazaki K, Narita M, Okado N. Increased monoamine concentration in the brain and blood of fetal thalidomide- and valproic acid-exposed rat: Putative animal models for autism. Pediatric Research. 2002;52:576–579. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200210000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen K, Brask D, Knudsen GM, Aznar S. Immunodetection of the serotonin transporter protein is a more valid marker for serotonergic fibers than serotonin. Synapse. 2006;59:270–276. doi: 10.1002/syn.20240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawara T, Katsuyama T, Ida-Eto M, Narita N, Narita M. Maternal viral infection during pregnancy impairs development of fetal serotonergic neurons. Brain and Development. 2015;37:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okaty BW, Freret ME, Rood BD, Brust RD, Hennessy ML, deBairos D, Dymecki SM. Multi-scale molecular deconstruction of the serotonin neuron system. Neuron. 2015;88:774–791. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onaivi ES, Benno R, Halpern T, Mehanovic M, Schanz N, Sanders C, Ali SF. Consequences of cannabinoid and monoaminergic system disruption in a mouse model of autism spectrum disorders. Current Neuropharmacology. 2011;9:209–214. doi: 10.2174/157015911795017047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piton A, Poquet H, Redin C, Masurel A, Lauer J, Muller J, Mandel JL. 20 ans apres: A second mutation in MAOA identified by targeted high-throughput sequencing in a family with altered behavior and cognition. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2014;22:776–783. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pobbe RL, Pearson BL, Defensor EB, Bolivar VJ, Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ. Expression of social behaviors of C57BL/6J versus BTBR inbred mouse strains in the visible burrow system. Behavioural Brain Research. 2010;214:443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompili M, Serafini G, Innamorati M, Moller-Leimkuhler AM, Giupponi G, Girardi P, Tatarelli R, Lester D. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and serotonin abnormalities: A selective overview for the implications of suicide prevention. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2010;260:583–600. doi: 10.1007/s00406-010-0108-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scattoni ML, Martire A, Cartocci G, Ferrante A, Ricceri L. Reduced social interaction, behavioural flexibility and BDNF signalling in the BTBR T + tf/J strain, a mouse model of autism. Behavioural Brain Research. 2013;251:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scattoni ML, Ricceri L, Crawley JN. Unusual repertoire of vocalizations in adult BTBR T+tf/J mice during three types of social encounters. Genes Brain Behavior. 2011;10:44–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schain RJ, Freedman DX. Studies on 5-hydroxyindole metabolism in autistic and other mentally retarded children. Journal of Pediatrics. 1961;58:315–320. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(61)80261-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seese RR, Maske AR, Lynch G, Gall CM. Long-term memory deficits are associated with elevated synaptic ERK1/2 activation and reversed by mGluR5 antagonism in an animal model of autism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:1664–1673. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JL, Yang M, Turner SM, Katz AM, Bell DB, Koenig JI, Crawley JN. Low stress reactivity and neuroendocrine factors in the BTBR T+tf/J mouse model of autism. Neuroscience. 2010;171:1197–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spratt EG, Nicholas JS, Brady KT, Carpenter LA, Hatcher CR, Meekins KA, Charles JM. Enhanced cortisol response to stress in children in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42:75–81. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1214-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squillace M, Dodero L, Federici M, Migliarini S, Errico F, Napolitano F, Gozzi A. Dysfunctional dopaminergic neurotransmission in asocial BTBR mice. Translational Psychiatry. 2014;4:e427. doi: 10.1038/tp.2014.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapley NW, Guariglia SR, Chadman KK. Cued and contextual fear conditioning in BTBR mice is improved with training or atomoxetine. Neuroscience Letter. 2013;549:120–124. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson DT, O’Neill SM, Narayan S, Tiwari A, Arnold E, Samaroo HD, Morton D. Histo-pathologic characterization of the BTBR mouse model of autistic-like behavior reveals selective changes in neurodevelopmental proteins and adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Molecular Autism. 2011;2:7. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe JS, Delahanty RJ, Prasad HC, McCauley JL, Han Q, Jiang L, Blakely RD. Allelic heterogeneity at the serotonin transporter locus (SLC6A4) confers susceptibility to autism and rigid-compulsive behaviors. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;77:265–279. doi: 10.1086/432648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, Corbett BA. A review of rhythm and responsiveness of cortisol in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;49:207–228. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra-VanderWeele J, Muller CL, Iwamoto H, Sauer JE, Owens WA, Shah CR, Blakely RD. Autism gene variant causes hyperserotonemia, serotonin receptor hypersensitivity, social impairment and repetitive behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:5469–5474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112345109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlsten D, Metten P, Crabbe JC. Survey of 21 inbred mouse strains in two laboratories reveals that BTBR T/+tf/tf has severely reduced hippocampal commissure and absent corpus callosum. Brain Research. 2003;971:47–54. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HH, Levitt P. Prenatal expression of MET receptor tyrosine kinase in the fetal mouse dorsal raphe nuclei and the visceral motor/sensory brainstem. Developmental Neuroscience. 2013;35:1–16. doi: 10.1159/000346367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Zhodzishsky V, Crawley JN. Social deficits in BTBR T+tf/J mice are unchanged by cross-fostering with C57BL/6J mothers. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2007;25:515–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]