Abstract

A neuroinflammatory response is commonly involved in the progression of many neurodegenerative diseases. Potassium 2-(1-hydroxypentyl)-benzoate (PHPB), a novel neuroprotective compound, has shown promising effects in the treatment of ischemic stroke and Alzheimer׳s disease (AD). In the present study, the anti-inflammatory effects of PHPB were investigated in the plasma and brain of C57BL/6 mice administered a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Levels of iNOS and the cytokines TNFα, IL-1β and IL-10 were elevated in plasma, cerebral cortex and hippocampus after LPS injection and the number of microglia and astrocytes in cortex and hippocampus were increased. LPS also upregulated the expression of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) in the cortex and hippocampus. PHPB reduced the levels of iNOS and cytokines in the plasma and brain, decreased the number of microglia and astrocytes and further enhanced the upregulation of HO-1. In addition, PHPB inhibited the LPS-induced phosphorylation of ERK, P38 and JNK. These results suggest that PHPB is a potential candidate in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases through inhibiting neuroinflammation.

KEY WORDS: PHPB, Neuroinflammation, LPS, MAPK, Heme oxygenase-1

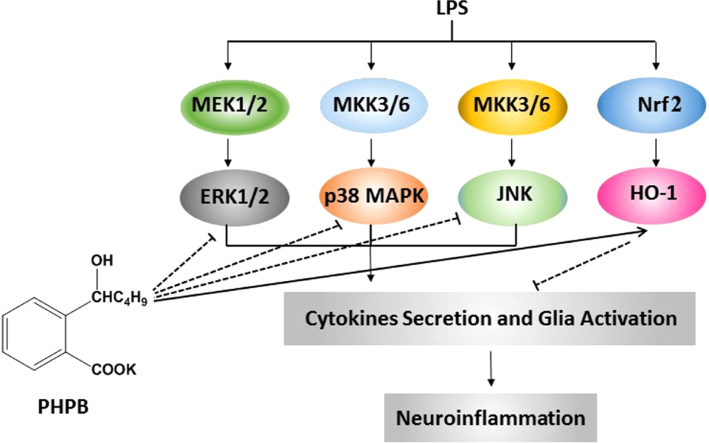

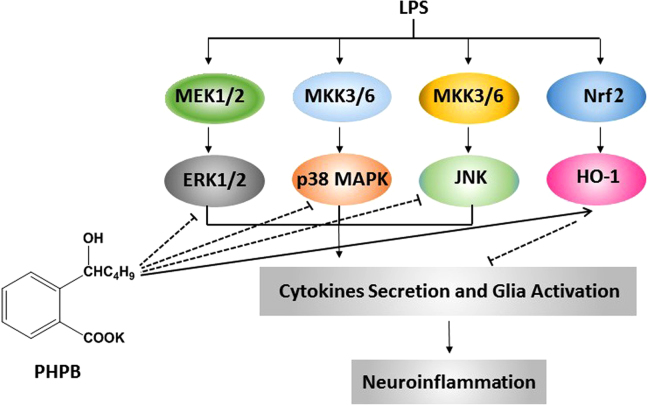

Graphical abstract

In this study, the neuroprotective effects of PHPB have been demonstrated in an in vivo brain injury model in mice. PHPB protected against LPS-induced neuroinflammation via inhibition of microglial activation resulting from attenuation of inflammatory cytokines, reduction of oxidative stress and downregulation of MAPK pathways.

1. Introduction

Neuroinflammation has recently been implicated as playing a critical role in the progression of damage in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer׳s disease (AD), Parkinson׳s disease (PD) and stroke1. Both glial activation and inflammatory mediator production are main features of neuroinflammation leading to neuronal apoptosis and associated neurodegeneration2, 3. Under pathological conditions, injured or diseased neurons cause resting microglia to become activated, transform into phagocytic cells, migrate to the site of the lesion and remove dead cells and debris. To do this, activated microglia release large amounts of cytotoxic pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as IL-1β, TNFα and nitric oxide (NO) which, in turn, lead to a vicious cycle of neuronal death4. Therefore, timely inhibition of microglial activation is considered a valuable strategy in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

Heme oxygenase (HO) can catalyze the conversion of heme to carbon monoxide and biliverdin with the concurrent release of iron which drives the synthesis of ferritin for iron sequestration5. HO-1 is an inducible isoform of HO with important anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic and anti-proliferative actions6, 7, 8. It has been reported that HO-1 activation modulates inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression9. Furthermore, silencing the HO-1 gene leads to an increase in LPS-induced expression of TNF-α and IL-1β whereas overexpression of HO-1 protein inhibits their generation, indicating that down-regulation of oxidative stress reduces the inflammatory response10.

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway has been shown to involve mediators producing inflammation in nerve and glial cells11, 12. In vivo and in vitro studies indicate that LPS initiates an inflammatory reaction through activating the MAPK family, including extracellular signal-related kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (P38)13, 14, 15. MAPK inhibitors can block Tnfα mRNA transcription and the LPS-induced increase in TNFα and IL-1β16, 17. The MAPK pathway has been shown to be involved in HO-1 protein activation18.

Potassium 2-(1-hydroxypentyl)-benzoate (PHPB) is a novel drug for the treatment of cerebral ischemia and is currently undergoing a phase II clinical trial in ischemic stroke in China. Recent studies have shown that PHPB improves cognitive impairments, reduces oxidative stress and glial activation and decreases neuronal degeneration in chronic cerebral hypoperfused rats, β-amyloid protein 1–40 (Aβ1–40)-intracerebroventricular-infused rats and APP/PS1-transgenic mice. The latter express a chimeric mouse/human APP containing the K595N/M596L Swedish mutations and a mutant human PS1 carrying the exon 9-deleted variant under the control of mouse prion promoter elements, directing transgene expression predominantly to neurons in central nervous system19, 20, 21, 22. Since the exact mechanism by which PHPB exerts a neuroprotective effect remains unknown, we decided to investigate the effect of PHPB on neuroinflammation and attempt to illuminate possible mechanisms.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

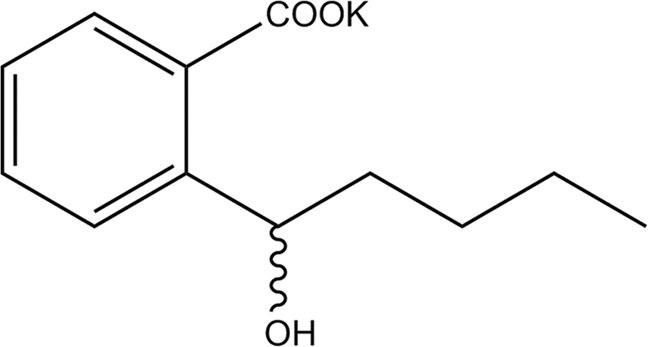

PHPB (purity > 98% by HPLC, Fig. 1) was synthesized by the Department of Medical Synthetic Chemistry, Institute of Materia Medica, Beijing, China. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Figure 1.

The chemical structure of PHPB.

2.2. Animals and treatment

Male C57BL/6 mice (8-week old) were purchased from Beijing HFK Bioscience Co., Ltd. (China). They were kept at a temperature of 24±1 °C and relative humidity of 50%–60% with a 12-h light–dark schedule with free access to food and water. All care and handling of animals was conducted in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the institutional Ethics Committee of the Experimental Animal Center of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Beijing, China).

Mice were randomly divided into four groups; control, LPS (4 mg/kg), LPS + 50 mg/kg PHPB, and LPS + 100 mg/kg PHPB. The mice were orally administered on a daily basis deionized water (control and LPS treated) or PHPB for 2 weeks. All groups except control were then administered a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of LPS (4 mg/kg) with the control group receiving an i.p. injection of the same volume of saline. Twenty-four hours later, mice were sacrificed for subsequent biochemical and pathological testing.

2.3. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of cytokine

The levels of TNFα (Biolegend, San Diego, USA), IL-1β (R&D System, Minneapolis, USA), IL-10 (Invitrogen, San Jose, USA) and iNOS (Cusabio, China) in plasma, cortex, and hippocampus were determined using ELISA kits according to the manufacturers׳ instructions. An aliquot (50 μL) of plasma and the supernatant of brain homogenate were added to a 96-well microtiter plate pre-coated with monoclonal antibody (coupled to HRP) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The plates were then thoroughly washed (with the washing solution provided by the kit) and substrate solution then added. Color was allowed to develop at 37 °C for 20 min before the reaction was stopped by adding stop solution. Absorbance values were recorded at 450 nm using a microplate reader (uQuant, Bio-Tek, USA) to generate a linear standard curve from which concentrations were calculated.

2.4. Tissue sample preparation

Mice were anesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate after which a blood sample was collected by cardiac puncture. After transcranial perfusion with 20–30 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), brains were dissected out and cut in half. One half was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and the other fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h followed by graded sucrose (10%–30%) and mounted on Tissue Tek surrounded with tissue freezing medium. Both halves were then stored at −80 °C until analysis. The coronal brain sample was cut into 20 μm thick slices using a Leica microtome (Leica RM 2135, Wetzlar, Germany). When the hippocampus was reached, every 15th section thereafter was chosen for analysis.

2.5. Western blot analysis

Proteins were extracted from cortex and hippocampus as described previously23. Subsequently 60 μg protein was loaded onto each lane for 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were then blocked with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T) for 2 h at room temperature after which they were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution at 4 °C overnight. The following primary antibodies were used for Western blot: rabbit polyclonal anti-p38 (Ser396) (1:500, Santa Cruz biotechnology, Dallas, Texas, USA); rabbit polyclonal anti-Phospho-p38 (Ser199) (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, USA); rabbit polyclonal anti-JNK (Ser404) (1:500, Santa Cruz biotechnology); rabbit polyclonal anti-Phospho-JNK (1:500, Santa Cruz biotechnology); rabbit polyclonal anti-ERK (1:500, Santa Cruz biotechnology); rabbit polyclonal anti-Phospho-ERK (1:500, Santa Cruz biotechnology); rabbit polyclonal anti-HO-1 (1:500, Santa Cruz biotechnology); mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (1:10,000, Sigma). After washing 5 times with TBS (each time for 5 min), membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG) at room temperature for 1 h, detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit and analyzed by densitometric evaluation using the Quantity-One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Densities were normalized to β-actin intensity levels.

2.6. Immunofluorescence analysis

Six coronal brain sections of each mouse were blocked in PBS containing 10% normal donkey serum and 0.3% (w/v) Triton X-100, followed by incubation with rat monoclonal anti-ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (anti-IBA1) (1:200; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Richmond, VA, USA), and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, 1:300, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) at 4 °C overnight. After washing, the sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-rat IgG (1:200; Invitrogen) for 2 h at room temperature in the dark.

The images of immunoreactivity of IBA-1 and GFAP were acquired using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and analyzed using Image-Pro Plus 5.1 (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA). The threshold of detection was kept constant during analysis. The percentages of the area occupied by IBA-1 and GFAP staining in the cortex and hippocampal areas were calculated for six equidistant sections per mouse.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean±the standard error (SE) of the mean. One-way analysis of variance was used for multiple comparisons using SPSS ver. 16.0 software. Differences for which P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

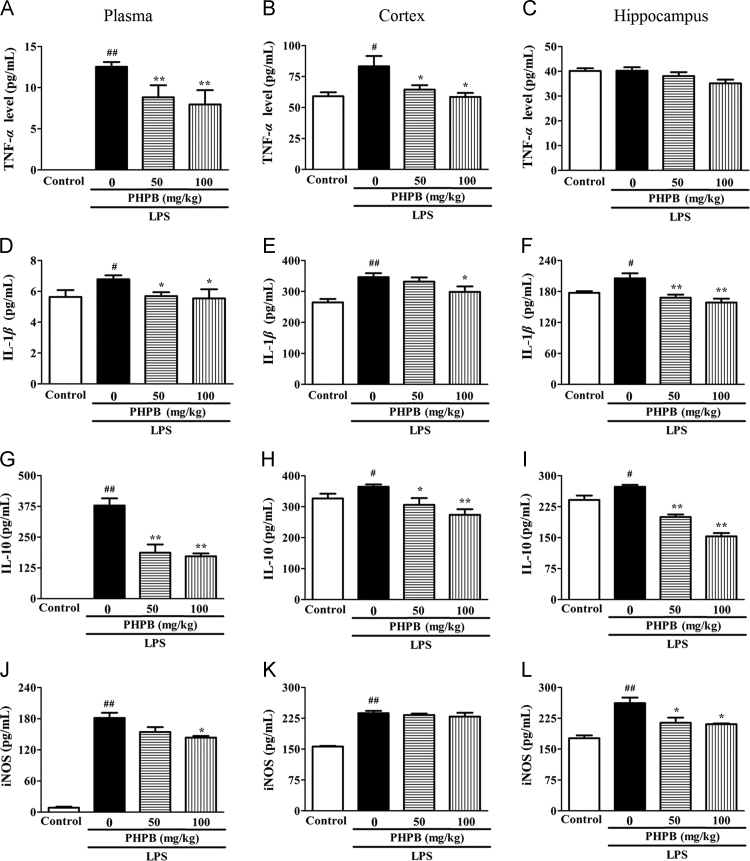

3.1. PHPB reduces the LPS-induced levels of inflammatory cytokines and iNOS

LPS significantly increased the production of TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-10 in plasma (Fig. 2A, D and G), cortex (Fig. 2B, E and H) and hippocampus (Fig. 2C, F and I). Pretreatment with PHPB 50 and 100 mg/kg reduced the increases in cytokines respectively as follows: Plasma TNFα 43% (P < 0.01) and 36% (P < 0.01); IL-1β 16% (P < 0.05) and 18% (P < 0.05); and IL-10 63% (P < 0.01) and 58% (P < 0.05); Cortex TNFα 22% (P < 0.05) and 29% (P < 0.05); IL-1β 6% and 16% (P < 0.05); and IL-10 16% (P < 0.05) and 25% (P < 0.01); Hippocampus TNFα 5% and 13% (P < 0.05); IL-1β 18% (P < 0.01) and 23% (P < 0.01); IL-10 27% (P < 0.01) and 44% (P < 0.01). LPS also significantly increased iNOS levels in plasma, cortex and hippocampus and, in this case, pretreatment with PHPB does-dependently inhibited iNOS expression in plasma and hippocampus but not in cortex (Fig. 2J–L).

Figure 2.

PHPB inhibits LPS-induced production of TNFα (A, B, C), IL-1β (D, E, F), IL-10 (I, J, K) and iNOS (L, M, N) in plasma, cortex and hippocampus. Male C57BL/6 mice pretreated with PHPB (50 or 100 mg/kg) by oral gavage were subsequently administered an i.p. injection of LPS. Values are mean ± SEM, n = 6–8 mice per group. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. control group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. LPS group. The levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in the control group are below the limits of detection.

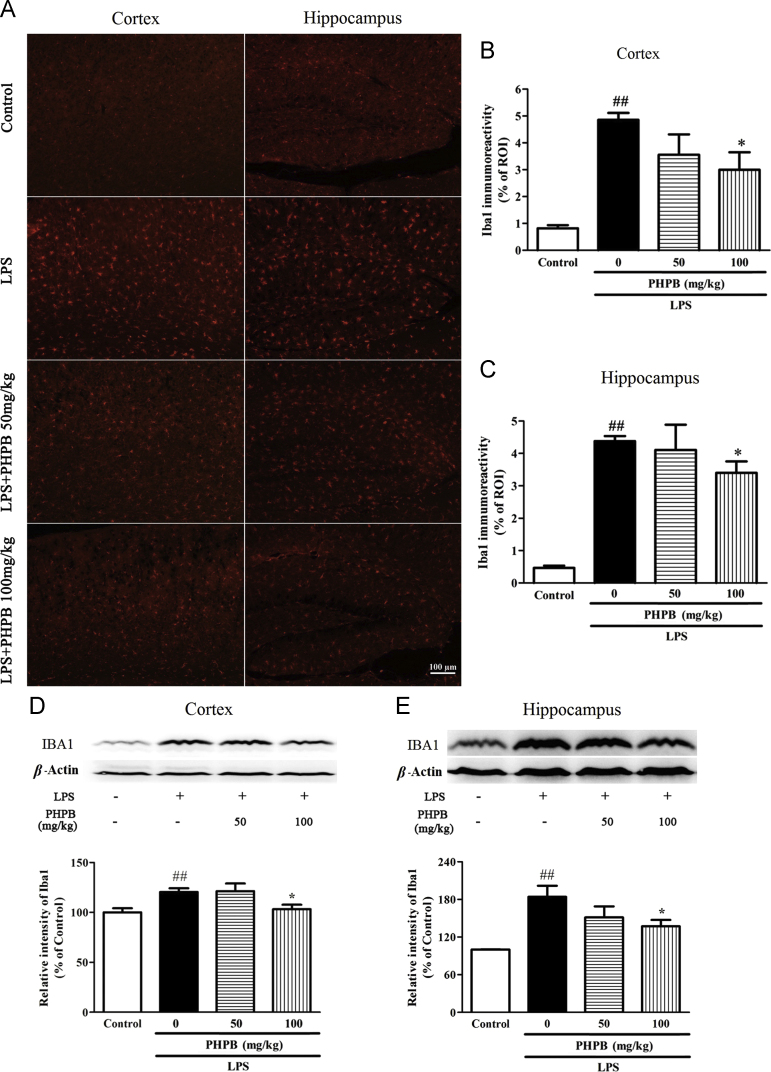

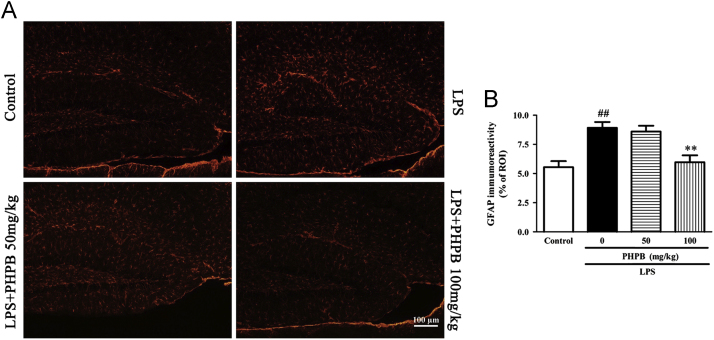

3.2. PHPB inhibits LPS-induced activation of microglia and astrocytes

Microglial activation occurs after systematic LPS administration and plays an important role in the neuroinflammation associated with neurodegenerative disorders24. As shown in Fig. 3, activated microglia underwent a conformational change towards shorter and thicker processes and increased size of cell bodies. Compared with the LPS treated group, pretreatment with the higher dose of PHPB (100 mg/kg) significantly decreased the number of IBA1-positive microglia in cortex and hippocampus by respectively 38% (P < 0.05) and 22% (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3A–C) and IBA-l protein expression by 14% (P < 0.05) and 26% (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3D and E). Similarly, LPS increased the number of GFAP‑positive astrocytes in the hippocampus, an increase that was reduced by PHPD 100 mg/kg pretreatment by 33% (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

PHPB inhibits LPS-induced microglial activation in the cortex and hippocampus. Male C57BL/6 mice were pretreated with PHPB (50 or 100 mg/kg) by oral gavage and subsequently administered an i.p. injection of LPS. Representative photographs of (A) IBA1 immuno-stained microglia of cortex and hippocampus. Statistical analysis showed PHPB significantly reduced IBA1 immunoreactivities of (B) cortex and (C) hippocampus. Representative images and quantitative analysis of IBA1 in (D) cortex and (E) hippocampus by Western blot. Values represent mean ± SEM, n = 5–6 mice per group. ##P < 0.01 vs. control group; *P < 0.05 vs. LPS group.

Figure 4.

PHPB inhibits LPS-induced astrocyte activation in the hippocampus. Male C57BL/6 mice were pretreated with PHPB (50 or 100 mg/kg) by oral gavage and subsequently administered an i.p. injection of LPS. Representative photographs of (A) GFAP immuno-stained astrocytes of hippocampus. Statistical analysis showed PHPB significantly reduced GFAP immunoreactivities in (B) hippocampus. Values represent mean ± SEM, n = 5–6 mice per group. ##P < 0.01 vs. control group; **P < 0.01 vs. LPS group.

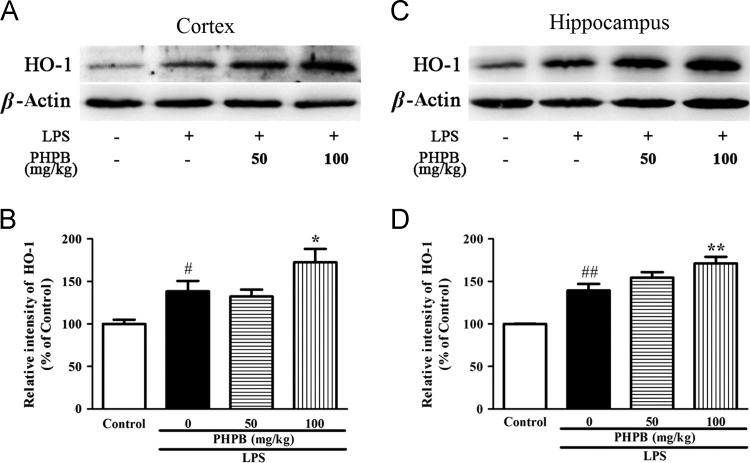

3.3. PHPB increases LPS-induced expression of HO-1

Since HO-1 induction reduced inflammation and oxidative stress25, the effect of PHPB on HO-1 production was also determined. LPS significantly elevated HO-1 expression by 21.9% (P < 0.05) and 34.8% (P < 0.01) in the cortex (Fig. 5A and B) and hippocampus (Fig. 5C and D), respectively. Interestingly, pretreatment with PHPB further enhanced HO-1 generation by 25% (P < 0.05) and 23% (P < 0.01), suggesting it exerts anti-inflammatory effects through multiple signals including MAPK and HO-1 signaling.

Figure 5.

PHPB upregulates HO-1 expression in the cortex and hippocampus of mice as shown in (A) representative Western blots. Quantitative analysis of HO-1 in (B) cortex and (C) hippocampus. Values are expressed as percentages compared to the control group (set to 100%) and are represented as mean ± SEM, n = 6–8 mice per group. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. control group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. LPS group.

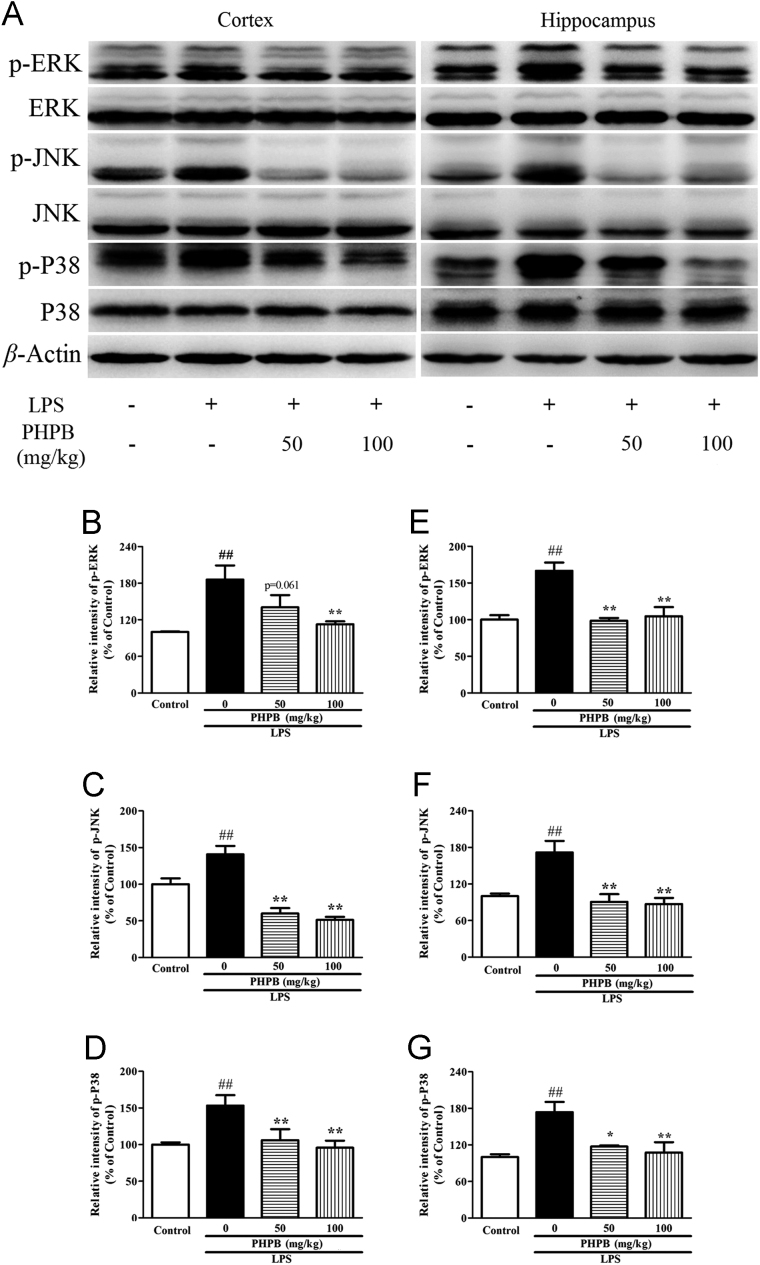

3.4. PHPB inhibits LPS-induced phosphorylation of the MAPK signaling pathway

The MAPK pathway is crucial in regulating pro-inflammatory substances. To determine the effects of PHPB and LPS on the MAPK pathway, the expression of phosphorylated and total ERK, JNK and P38 were examined by Western blot. LPS induced the phosphorylation of ERK, JNK, and P38 in both cortex and hippocampus, indicating it is a potent activator of all three MAPK signaling pathways. Pretreatment with PHPB significantly lowered the levels of all three MAP kinases particularly at the higher concentration where the reductions in cortex and hippocampus were respectively: Phosphor-ERK 39% (P < 0.05) and 34% (P < 0.05); phosphor-JNK 56% (P < 0.01) and 49% (P < 0.01); and phosphor-P38 31% (P < 0.05) and 38% (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6A–G). In contrast, the levels of total-ERK, JNK and P38 were not changed among the groups.

Figure 6.

Effects of PHPB on LPS-induced MAPK activity in the cortex and hippocampus of mice as shown in (A) representative Western blots of p-ERK and ERK, p-JNK and JNK and p-P38 and P38. Quantitative analysis of (B, C and D) p-ERK, p-JNK and p-P38 in the cortex and (E, F and G) in the hippocampus. Values are expressed as percentages compared to control group (set to 100%) and are represented as mean ± SEM. n = 5–6 mice per group. ##P < 0.01 vs. control group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. LPS group.

4. Discussion

Significant neuroinflammation is observed in patients and mouse models of neurodegenerative diseases26 where peripheral inflammation can exacerbate local brain inflammation and neuronal death27. The search for compounds that can effectively reduce neuroinflammation is a new strategy for improving the pharmacotherapy of neurodegenerative diseases28, 29, 30. PHPB has been shown to provide effective neuroprotection in previous studies by our group19, 20, 21, 22. In the present study, we investigated the effects of PHPB on LPS-induced microglial activation and the production of inflammatory cytokines. Furthermore, we investigated its effect on MAPK signaling pathway and oxidative stress in the brain in a mouse model of systemic inflammation.

Microglia are the principal innate immune cells resident in the CNS where they contribute to its normal development and maintain and protect the plasticity of neuronal networks31. Activated microglia produce several proinflammatory signal molecules including cytokines such as TNFα and IL-1β, growth factors, complement molecules, chemokines and cell adhesion molecules. Some cytokines are clearly proinflammatory whereas others such as IL-10 and IL-4 are anti-inflammatory in that they suppress the activity of proinflammatory cytokines32. In this study, LPS increased the size of microglial cell bodies and shortened their axons making them amoeba-like in appearance. PHPB significantly attenuated microglial activation and reversed LPS-induced secretions of TNFα and IL-1β in plasma and brain. However, IL-10 levels were increased in the cortex, hippocampus and plasma after LPS stimulation. This indicates that in response to inflammation, glial cells release more anti-inflammatory cytokines to counteract the consequences of upregulated proinflammatory cytokines. After PHPB administration, IL-10 expression was significantly reduced, suggesting that PHPB may balance the interaction between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and reduce brain inflammation.

Activation of microglia in the brain can lead to excessive release of NO which plays an important role in the inflammatory response33. Until now it was assumed that during the inflammatory response, NO is produced mainly by the inducible isoform of iNOS and that synthesis of NO by both the iNOS isoforms contributes to activation of apoptotic pathways in the brain34. Therefore, the content of iNOS largely reflects the level of NO. In the present study, LPS induced a significant increase in iNOS levels in plasma and brain homogenate which were subsequently lowered by PHPB treatment. The results show albeit indirectly that PHPB reduces brain inflammation by inhibiting the NO signaling pathway.

The MAPK family of serine/threonine protein kinases is responsible for most cellular responses to cytokines and external stress signals and crucial for the regulation of inflammatory mediators in three core pathways involving ERK1/2, JNK1/2/3 and P3817, 35, 36. The MAPK signaling pathway regulates secretion of cytokines by microglia37, 38. Increased activities of MAPKs in activated microglia and their regulatory role in the synthesis of inflammatory cytokine mediators make them potential targets for novel therapeutics. We found LPS significantly increased phosphorylation levels of ERK, JNK and P38 in the cortex and hippocampus of mice and subsequent PHPB treatment decreased the expression of the three kinases. Thus it appears that PHPB simultaneously acts on the three pathways to regulate the secretion of inflammatory cytokines and inhibit neuroinflammation.

In response to certain environmental toxins such as LPS, microglia are activated to release reactive oxygen species (ROS) that cause neurotoxicity2. It is well known that the neuroinflammatory process and the ROS associated with β-amyloid may participate in the development of AD39. On the other hand, intracellular ROS can act as second messengers to trigger the kinase cascade and related transcription factors that regulate the expression of inflammatory cytokines and antioxidant proteins. HO-1 is one of the most representative antioxidant and anti-inflammatory proteins. The HO system includes the heme catabolic pathway comprising HO and biliverdin reductase and the products of heme degradation viz carbon monoxide (CO), iron, and biliverdin/bilirubin. HO-1 induction coupled with ferritin synthesis is a rapid, protective and antioxidant response in vivo. HO-1/CO activation down-regulates the inflammatory response by blocking the release of NO and iNOS expression40. Our results show that LPS upregulates HO-1 expression in the cortex and hippocampus. We speculate that this is a compensatory response against LPS-induced neuroinflammation. As expected, PHPB continued to increase HO-1 expression in both cortex and hippocampus to mediate its anti-inflammatory effects.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the neuroprotective effects of PHPB have been demonstrated in an in vivo brain injury model in mice. PHPB protection against LPS-induced neuroinflammation was mediated through inhibition of microglial activation resulting from attenuation of inflammatory cytokines (TNF, IL-1 and IL-6), reduction of oxidative stress and downregulation of MAPK pathways (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

The mechanism of PHPB on its neuroprotective effects.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81373387) and the Beijing Key Laboratory of New Drug Mechanisms and Pharmacological Evaluation Studies (BZ0150).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

Contributor Information

Xiaoliang Wang, Email: wangxl@imm.ac.cn.

Ying Peng, Email: ypeng@imm.ac.cn.

References

- 1.McCoy M.K., Tansey M.G. TNF signaling inhibition in the CNS: implications for normal brain function and neurodegenerative disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:45. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Block M.L., Zecca L., Hong J.S. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu B., Hong J.S. Role of microglia in inflammation-mediated neurodegenerative diseases: mechanisms and strategies for therapeutic intervention. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:1–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.035048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Streit W.J., Walter S.A., Pennell N.A. Reactive microgliosis. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;57:563–581. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willis D. Expression and modulatory effects of heme oxygenase in acute inflammation in the rat. Inflamm Res 1995;44 Suppl 2:S218–S220 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Dinkova-Kostova AT, Talalay P. Direct and indirect antioxidant properties of inducers of cytoprotective proteins. Mol Nutr Food Res 2008;52 Suppl 1:S128–S138 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Su Z.Y., Shu L., Khor T.O., Lee J.H., Fuentes F., Kong A.N. A perspective on dietary phytochemicals and cancer chemoprevention: oxidative stress, Nrf2, and epigenomics. Top Curr Chem. 2013;329:133–162. doi: 10.1007/128_2012_340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otterbein L.E., Soares M.P., Yamashita K., Bach F.H. Heme oxygenase-1: unleashing the protective properties of heme. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:449–455. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Velagapudi R., Aderogba M., Olajide O.A. Tiliroside, a dietary glycosidic flavonoid, inhibits TRAF-6/NF-κB/p38-mediated neuroinflammation in activated BV2 microglia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840:3311–3319. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rushworth S.A., MacEwan D.J., O׳Connell M.A. Lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 and heme oxygenase-1 protects against excessive inflammatory responses in human monocytes. J Immunol. 2008;181:6730–6737. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorina R., Font-Nieves M., Márquez-Kisinousky L., Santalucia T., Planas A.M. Astrocyte TLR4 activation induces a proinflammatory environment through the interplay between MyD88-dependent NFκB signaling, MAPK, and Jak1/Stat1 pathways. GLIA. 2011;59:242–255. doi: 10.1002/glia.21094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao S., Zhang L., Lian G., Wang X., Zhang H., Yao X. Sildenafil attenuates LPS-induced pro-inflammatory responses through down-regulation of intracellular ROS-related MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathways in N9 microglia. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeong Y.H., Kim Y., Song H., Chung Y.S., Park S.B., Kim H.S. Anti-inflammatory effects of α-galactosylceramide analogs in activated microglia: involvement of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee K.M., Bang J.H., Han J.S., Kim B.Y., Lee I.S., Kang H.W. Cardiotonic pill attenuates white matter and hippocampal damage via inhibiting microglial activation and downregulating ERK and p38 MAPK signaling in chronic cerebral hypoperfused rat. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:334. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao H., Cheng L., Liu Y., Zhang W., Maharjan S., Cui Z. Mechanisms of anti-inflammatory property of conserved dopamine neurotrophic factor: inhibition of JNK signaling in lipopolysaccharide-induced microglia. J Mol Neurosci. 2014;52:186–192. doi: 10.1007/s12031-013-0120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bachstetter A.D., Xing B., de Almeida L., Dimayuga E.R., Watterson D.M., Van Eldik L.J. Microglial p38α MAPK is a key regulator of proinflammatory cytokine up-regulation induced by toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands or beta-amyloid (Aβ) J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:79. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong C., Davis R.J., Flavell R.A. MAP kinases in the immune response. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:55–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.091301.131133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J.C., Tseng C.K., Young K.C., Sun H.Y., Wang S.W., Chen W.C. Andrographolide exerts anti-hepatitis C virus activity by up-regulating haeme oxygenase-1 via the p38 MAPK/Nrf2 pathway in human hepatoma cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:237–252. doi: 10.1111/bph.12440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu Y., Peng Y., Long Y., Xu S., Feng N., Wang L. Potassium 2-(1-hydroxypentyl)-benzoate attenuated hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis in neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;680:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li P.P., Wang W.P., Liu Z.H., Xu S.F., Lu W.W., Wang L. Potassium 2-(1-hydroxypentyl)-benzoate promotes long-term potentiation in Aβ1–42-injected rats and APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2014;35:869–878. doi: 10.1038/aps.2014.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng Y., Hu Y., Xu S., Rong X., Li J., Li P. Potassium 2-(1-hydroxypentyl)-benzoate improves memory deficits and attenuates amyloid and τ pathologies in a mouse model of Alzheimer׳s disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;350:361–374. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.213140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao W., Xu S., Peng Y., Ji X., Cao D., Li J. Potassium 2-(1-hydroxypentyl)-benzoate improves learning and memory deficits in chronic cerebral hypoperfused rats. Neurosci Lett. 2013;541:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elbirt K.K., Whitmarsh A.J., Davis R.J., Bonkovsky H.L. Mechanism of sodium arsenite-mediated induction of heme oxygenase-1 in hepatoma cells. Role of mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8922–8931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qin L., Wu X., Block M.L., Liu Y., Breese G.R., Hong J.S. Systemic LPS causes chronic neuroinflammation and progressive neurodegeneration. GLIA. 2007;55:453–462. doi: 10.1002/glia.20467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin H., Ji M., Chen L., Liu Q., Che S., Xu M. The clinicopathological significance of mortalin overexpression in invasive ductal carcinoma of breast. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35:42–50. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0316-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glass C.K., Saijo K., Winner B., Marchetto M.C., Gage F.H. Mechanisms underlying inflammation in neurodegeneration. Cell. 2010;140:918–934. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cunningham C., Wilcockson D.C., Campion S., Lunnon K., Perry V.H. Central and systemic endotoxin challenges exacerbate the local inflammatory response and increase neuronal death during chronic neurodegeneration. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9275–9284. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2614-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solberg N.O., Chamberlin R., Vigil J.R., Deck L.M., Heidrich J.E., Brown D.C. Optical and SPION-enhanced MR imaging shows that trans-stilbene inhibitors of NF-κB concomitantly lower Alzheimer׳s disease plaque formation and microglial activation in AβPP/PS-1 transgenic mouse brain. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;40:191–212. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buendia I., Navarro E., Michalska P., Gameiro I., Egea J., Abril S. New melatonin-cinnamate hybrids as multi-target drugs for neurodegenerative diseases: Nrf2-induction, antioxidant effect and neuroprotection. Future Med Chem. 2015;7:1961–1969. doi: 10.4155/fmc.15.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peñaaltamira E., Prati F., Massenzio F., Virgili M., Contestabile A., Bolognesi M.L. Changing paradigm to target microglia in neurodegenerative diseases: from anti-inflammatory strategy to active immunomodulation. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2016;20:627–640. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2016.1121237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gertig U., Hanisch U.K. Microglial diversity by responses and responders. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:101. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubio-Perez J.M., Morillas-Ruiz J.M. A review: inflammatory process in Alzheimer׳s disease, role of cytokines. Sci World J. 2012;2012:756357. doi: 10.1100/2012/756357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Possel H., Noack H., Putzke J., Wolf G., Sies H. Selective upregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and cytokines in microglia: in vitro and in vivo studies. GLIA. 2000;32:51–59. doi: 10.1002/1098-1136(200010)32:1<51::aid-glia50>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Czapski G.A., Cakala M., Chalimoniuk M., Gajkowska B., Strosznajder J.B. Role of nitric oxide in the brain during lipopolysaccharide-evoked systemic inflammation. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:1694–1703. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaminska B., Gozdz A., Zawadzka M., Ellert-Miklaszewska A., Lipko M. MAPK signal transduction underlying brain inflammation and gliosis as therapeutic target. Anat Rec. 2009;292:1902–1913. doi: 10.1002/ar.21047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kyriakis J.M., Avruch J. Mammalian MAPK signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation: a 10-year update. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:689–737. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhat N.R., Zhang P., Lee J.C., Hogan E.L. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 subgroups of mitogen-activated protein kinases regulate inducible nitric oxide synthase and tumor necrosis factor-α gene expression in endotoxin-stimulated primary glial cultures. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1633–1641. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01633.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Culbert A.A., Skaper S.D., Howlett D.R., Evans N.A., Facci L., Soden P.E. MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 deficiency in microglia inhibits pro-inflammatory mediator release and resultant neurotoxicity. Relevance to neuroinflammation in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23658–23667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lim C.S., Jin D.Q., Mok H., Oh S.J., Lee J.U., Hwang J.K. Antioxidant and antiinflammatory activities of xanthorrhizol in hippocampal neurons and primary cultured microglia. J Neurosci Res. 2005;82:831–838. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abraham N.G., Kappas A. Pharmacological and clinical aspects of heme oxygenase. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:79–127. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]