Summary

Prenatal ethanol exposure, like other early adverse experiences, is known to alter hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) activity in adulthood. The present study examined the modulatory effects of the gonadal hormones on basal HPA regulation and serotonin type 1A receptor (5-HT1A) levels in adult female rats prenatally exposed to ethanol (E) compared to that in females from pair-fed (PF) and ad libitum-fed control (C) conditions.

We demonstrate, for the first time, long-lasting consequences of prenatal ethanol exposure for basal corticosterone (CORT) regulation and basal levels of hippocampal mineralocorticoid (MR), glucocorticoid (GR) and serotonin type 1A (5-HT1A) receptor mRNA, as a function of estrous cycle stage: 1) basal CORT levels were higher in E compared to C females in proestrus but lower in E and PF compared to C females in estrus; 2) there were no differences among groups in basal levels of adrenocorticotropin (ACTH), estradiol or progesterone; 3) hippocampal MR mRNA levels were decreased in E compared to PF and C females across the estrus cycle, with the greatest effects in proestrus, whereas E (but not PF or C) females had higher hippocampal GR mRNA levels in proestrus than in estrous and diestrus; 4) 5-HT1A mRNA levels were increased in E compared to PF and C females in diestrus. That alterations were revealed as a function of estrous cycle stage suggests a role for the ovarian steroids in mediating the adverse effects of ethanol. Furthermore, it appears that ethanol-induced nutritional effects may play a role in mediating at least some of the effects observed.

The resetting of HPA activity by early environmental events could be one mechanism linking early life experiences with long-term health consequences. Thus, changes in basal CORT levels, a shift in the MR/GR balance and alterations in 5-HT1A receptor mRNA could have important clinical implications for understanding the secondary disabilities, such as an increased incidence of depression, in children with FASD.

Keywords: Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA), serotonin (5-HT) receptors, glucocoticoid receptor (GR), mineralocorticoid receptor (MR), prenatal ethanol exposure, depression

Introduction

The concept that early environmental or nongenetic factors can permanently organize or imprint physiological and behavioral systems is called fetal or early programming (Bakker et al., 2001; Matthews, 2002; Welberg and Seckl, 2001). Importantly, the resetting of key hormonal systems by early environmental events may be one mechanism linking early life experiences with long-term health consequences. The HPA axis is highly susceptible to programming during fetal and neonatal development (Matthews, 2002), and is likely one of the key systems involved in mediating the long-term consequences of early life experiences. Moreover, data suggest that the serotonergic (5-HT) system is a primary system involved in HPA programming (Andrews and Matthews, 2004).

Data from our laboratory and others indicate that prenatal ethanol exposure programs the fetal HPA axis such that HPA tone is increased throughout life [for review see: (Sliwowska et al., 2006; Weinberg et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2005)]. Importantly, because ethanol is known to activate the HPA axis, in this animal model, fetuses are exposed to both ethanol and CORT, both of which cross the placenta, and both of which can reprogram the HPA axis to result in hyperresponsiveness to stressors in adulthood. Animal exposed to ethanol in utero show increased HPA activation and/or delayed or deficient recovery to basal levels following stress (Kim et al., 1996; Lee et al., 2000; Nelson et al., 1986; Taylor et al., 1988; Taylor et al., 1984; Weinberg, 1988; 1993b). These changes appear to reflect both increased HPA drive and deficits in feedback regulation of HPA activity, and/or an altered balance between drive and feedback (Glavas et al., 2007; Glavas et al., 2006; Lee et al., 1990; Lee et al., 2000; Weinberg, 1993b).

Importantly, evidence suggests an increased incidence of mental health problems in children and adults with prenatal alcohol exposure, including emotional and psychiatric disorders, and among these, a high incidence of depression and anxiety disorders (Famy et al., 1998; O’Connor and Paley, 2006; Streissguth et al., 1996). Whether fetal programming of HPA activity underlies the increased vulnerability to depression and anxiety disorders remains to be determined, but it is certainly a strong possibility.

There is a growing body of evidence for the role of 5-HT1A receptors in both the effects of prenatal ethanol exposure and the pathology of depression. We have shown that in adulthood, females prenatally exposed to ethanol (E) have a greater hypothermic response, a blunted ACTH response and increased hippocampal 5HT1A receptor expression in response to the 5HT1A agonist 8-OH-DPAT (Hofmann et al., 2007). Similarly, E females show increased 5HT1A-dependent anxiety-like behavior compared to controls (Hofmann et al., 2005). In humans, selective 5HT1A agonists, such as buspirone, can effectively treat depression (Fabre, 1990; Robinson et al., 1990). Moreover, in view of the involvement of the serotonergic system in fetal programming of the HPA axis (Andrews and Matthews, 2004), it is also important to understand the role of this system in the HPA programming of animals prenatally exposed to ethanol.

The brain serotonin system and the HPA axis interact closely and in a complex manner. Early studies suggested that, in general, serotonin stimulates the activity of the HPA axis, and that the 5-HT1A receptor plays a major role in this relationship (Chaouloff, 1993; 1995). Paradoxically, however, more recent studies have shown that serotonin may contribute to either facilitation or inhibition of basal and stress-induced glucocorticoid secretion, and that its action may be dependent on the specific nature of the stressor or the circuitry involved (Lowry, 2002). It is well known that different types of stress-related stimuli utilize different neural systems to modulate HPA activity (Herman et al., 1989). These different neuronal circuits might in turn be modulated by different serotonergic systems (Lowry, 2002). Circulating corticosteroids, on the other hand exert an inhibitory effect on expression of the hippocampal 5-HT1A receptor (Chaouloff, 1993; 1995). Prolonged exposure to elevated CORT levels attenuates hippocampal 5-HT and 5-HT1A receptor-mediated responses (Joels and Van Riel, 2004). Further, chronic stress decreases hippocampal 5-HT1A mRNA (Flugge et al., 1998; Joels and Van Riel, 2004), whereas removal of circulating steroids by adrenalectomy (ADX) increases hippocampal 5-HT1A mRNA and receptor binding (Chalmers et al., 1993; Kuroda et al., 1994; Meijer and de Kloet, 1994; Mendelson and McEwen, 1992; Zhong and Ciaranello, 1995).

The direct action of corticosterone is mediated by high affinity mineralocorticoid or Type I receptors (MRs) and low affinity glucocorticoid or Type II receptors (GRs). MRs are extensively occupied by endogenous CORT even under basal conditions, while GRs become occupied concurrently with increasing plasma CORT concentrations due to stress or the diurnal rhythm (de Kloet et al., 1990; Reul et al., 1987). Data suggest that the hippocampus, where the MR, GR and 5-HT1A receptors are particularly abundant, is one of the principal brain structure involved in regulating HPA negative feedback is (Morimoto et al., 1996; Van Eekelen et al., 1988). The ascending serotonergic innervation of hippocampal neurons arises in midbrain raphe nuclei and provides a means by which the 5HT system may act to regulate HPA function. Thus the hippocampus represent a unique anatomical environment in which to study the interplay between the serotonergic and HPA systems (Lopez et al., 1998). The hipppocampus both tonically inhibits HPA tone and contributes to the negative feedback suppression of stress-initiated activity (Reul and de Kloet, 1985). MRs play a role in controlling the threshold or sensitivity of the stress response system, while GRs play a role in terminating the stress response and promoting recovery from stress (de Kloet et al., 2005). The effect of corticosteroids in the hippocampus is considered in the present study in terms of the MR/GR balance as a factor protective against stress-related disorders. According to this concept, a change in the balance of MR- and GR- mediated events alters the ability to maintain homeostasis and progressively creates a condition of disrupted neuroendocrine regulation and impaired behavioural adaptation. Receptor imbalance, which could be induced by stressful events, is reflected as a change in drive and feedback, and in turn alters stress responsiveness and behavioural adaptation, and may thus result in enhanced vulnerability to stress-related brain disorders (De Kloet et al., 1998).

Sex differences in normal HPA activity are well established in animal models, with enhanced CORT and/or adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) secretion in response to physical and psychological stressors observed in females compared to males (Burgess and Handa, 1992; Carey et al., 1995; Figueiredo et al., 2002; Handa et al., 1994; Viau and Meaney, 1991). In addition to this normal sexual dimorphism, prenatal ethanol exposure differentially affects female and male offspring, suggesting a role for the sex steroids in mediating prenatal ethanol effects on the HPA axis (Lan et al., 2006; Lee and Rivier, 1996; Sliwowska et al., 2006; Weinberg, 1988; 1992a; Yamashita et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2005). However, the estrous cycle has typically not been considered as a factor in studies examining the effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on females.

In the present study, we examine for the first time the modulatory effects of the ovarian steroids on basal HPA regulation in adult female rats exposed to ethanol in utero. Specifically, we examine basal CORT activity as well as basal levels of hippocampal MR, GR and 5-HT1A mRNA as a function of estrous cycle stage. We hypothesized that prenatal ethanol exposure will alter the MR/GR balance and in turn disrupt neuroendocrine regulation, which could underlie the HPA hyperresponsiveness observed in E females. Further, we hypothesized that alterations will be manifested differentially as a function of the estrous cycle.

Methods

Breeding of animals

Adult virgin female (250–275 g) and male (300–350 g) Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (St Constant, PQ, Canada). Rats were group-housed by sex and maintained on 12:12 h light/dark cycle (lights on 6:00 h). The colony room had controlled temperature (21–22°C). Animals were given ad libitum access to water and standard rat chaw (Jamieson’s Pet Food Distributors Ltd, Delta, BC, Canada). One to two weeks following arrival, each female was paired with a male in a stainless steel suspended cage (25 × 18 × 18 cm), with mesh front and floor. Wax paper was placed under the cages and checked daily for the presence of vaginal plugs, which indicated day 1 of gestation (G1). Once a vaginal plug was found, the females were singly housed in clear polycarbonate cages lined with bedding and were assigned to experimental groups, as described below. All animal procedures were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of British Columbia Animal Care Committee. Efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to reduce the number of animals used.

Prenatal Treatments

On day 1 of gestation (GD1), females were singly housed in polycarbonate cages (24 × 16 × 46 cm) with pine shavings bedding, and were randomly assigned to one of three groups: 1) Ethanol (E), liquid ethanol diet, ad lib (n = 9); 2) Pair-fed (PF), liquid control diet in the amount consumed by an E partner (g/kg/body wt/day of gestation) which controls for the nutritional effects of ethanol intake (n = 10); 3) Control (C), lab chow, ad libitum (n = 10). Females in the E and PF groups were weight- matched, and all females had ad libitum access to water.

Ethanol was administered to pregnant females throughout gestation using liquid diets formulated in our laboratory to provide optimal nutrition, with 36% of the total calories derived from ethanol. Maltose-dextrin is isocalorically substituted for ethanol in the liquid control diet (PF group). Diets were supplied by Dyets, Inc., Bethlehem, PA. Fresh diets were presented daily at 1600–1700h. This feeding schedule permits maintenance of relatively normal corticoid rhythms in the PF dams, as the corticoid rhythm in animals receiving a reduced ration, such as PF animals, re-entrains to the time of feeding (Gallo and Weinberg, 1981). Every day bottles from the previous day were removed and weighed to determine the amount of diet consumed. Experimental diets continued until GD 21, at which time they were replaced with standard laboratory chow and water ad libitum. We have shown that pregnancy outcome and lactation are more successful if the alcohol diet is removed prior to parturition (Weinberg, 1989). Pregnant females were handled only on GD 1, 7, 14 and 21 for weighing and cage changing. On postnatal day 1 (PND 1), pups were weighed and litters were randomly culled to 10, (5 females and 5 males when possible), to control for any confounding effects of litter size or sex ratio. All litters were reared by their biological mothers. Dams and pups were weighed on PND 1, 8, 15 and 22 and pups were weaned on PND 22, after which the offspring were grouped-housed by litter and sex, with ad libitum access to standard rat chow and water.

Blood Alcohol Level (BAL) Measurements

To determinate the maximal or near maximal BAL achieved by ethanol-treated dams, tail blood samples were taken from three randomly selected females on GD 15, 2 h after lights off, when a major eating bout has typically occurred. Blood samples were allowed to coagulate for 2 h at room temperature and then spun down at 3000 r.p.m. for 20 min. at 4°C. Serum was collected and stored at − 20°C until the time of assay. BALs were measured using Pointe Scientific Inc. Alcohol Reagent Set (Lincoln Park, Mi, USA). The minimum detectable concentration of ethanol is 2 mg/dl.

Testing

Determination of the estrous stage

Vaginal smears were taken for five consecutive days, two weeks prior to testing, to determinate whether animals were cycling normally. Vaginal smears were taken again 1–3 days before testing, and used to assign rats to groups according to estrous cycle stage: diestrus (metestrus and diestrus combined), proestrus, estrus. The proportion of three types of cells was used for the determination of estrous cycle stage. Thus, the proestrus smear consisted of a predominance of nucleated epithelial cells, the estrus smear consisted primarily of anucleated cornified cells, and the diestrus smear consisted of a mix of leucocytes, cornified and nucleated epithelial cells (Marcondes et al., 2002).

Brain and blood collection

Adult female offspring (90–120 days) were terminated by rapid decapitation right after removing from home cages. Trunk blood was collected to determine plasma levels of adrenocorticotropin (ACTH), corticosterone (CORT), estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4). Brains were rapidly removed and immediately frozen on dry ice, then stored at −70°C until sectioning.

In situ hybridization

Brains were sectioned coronally on a cryostat at 14 μm through the hippocampus. Six slides were collected from each brain, with 4 sections per slide. Sections were mounted on poly-L-lysine/gelatin-coated slides, thawed briefly and then stored at −70°C until analysis by in situ hybridization. For each probe, all slides were hybridized at the same time. MR and GR cRNA probes were kindly provided by Dr. James P. Herman, University of Cincinnati, USA and were 550-bp and 456-bp EcoRI fragmented inserts, respectively (Herman et al., 1989). The 5-HT1A probe was a 47-bp oligo (Chen et al., 1995) prepared at the Oligonucleotide Synthesis Laboratory at UBC. For cRNA probes (MR and GR), sections were fixed for 60 min in 10% buffered formalin followed by two washes in 1X PBS for 10 min and digested in proteinase K (100 μg/L, at 37C for 9 min.). Sections were then rinsed in DEPC treated water for 5 min, 0.1M triethanolamine/0.25% acetic anhydride for 10 min, given 2 washes in 2X SSC for 5 min, and dehydrated through 50% (1 min), 75% (1 min), 95% (2 min) and 100% (1 min) ethanol, chloroform (5 min), and 100% ethanol (1 min). Sections were then air-dried for 30 min. Next, 30 μl of hybridization buffer (75% formamide, 3X SSC, 1X Denhardt’s solution, 200 μg/ml yeast tRNA, 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH=7.4), 10% dextran sulfate, 10 mM dithiothreitol) was applied to each section. MR probe activity was 6×105 cpm/section and GR probe activity was 3.8×105 cpm/section. Sections were covered with Hybrislips (Sigma) and slides were incubated overnight at 55oC in a chamber saturated with 75% formamide. Following incubation, hybrislips were removed. Sections were washed in 2X SSC for 60 min. Next slides were transferred to 50 μg/ml RNase A solution (37oC, 45 min), followed by washes in 2X SSC (10 min); 1X SSC (10 min); 0.5X SSC (55 C, 60 min); 0.5X SSC (5 min); 0.1X SSC (10 min), dehydrated through 50%, 70%, 95% and 100% ethanol and then air-dried for 30 min.

For oligonucleotide probe (5-HT1A), sections were fixed for 45 min in 10% buffered formalin followed by two washes in 1X PBS for 10 min each, 0.1M triethanolamine/0.25% acetic anhydride for 10 min, 2 washes in 2X SSC for 5 min, dehydrated through 50% (1 min), 75% (1 min), 95% (2 min) and 100% (1 min) ethanol, chloroform for 5 min, and 100% ethanol (1 min). Sections were then air-dried for 30 min. Next, 30 μl of hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 3X SSC, 1X Denhardt’s solution, 200 μg/ml yeast tRNA, 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH=7.4), 10% dextran sulfate, 10 mM dithiothreitol) was applied to each section. Probe activity for 5-HT1A was 1.2×105 cpm/section and slides were covered with Hybrislips. Slides were incubated overnight at 38oC in a chamber saturated with 50% formamide. Following incubation, hybrislips were removed. Slides were washed in 2X SSC (30 min) followed by washes in 2X SSC (30 min); 2X SSC/DTT (40oC, 15min), 1X SSC/DTT (40oC, 15min), 1X SCC/50% Formamide (40oC, 30 min); 1X SSC (10 min); 0.5X SSC (10 min); 5 quick dips in distilled water, dehydrated in 70% ethanol and then air-dried for 30 min.

Slides were exposed to BioMax MR film (Kodak) for 3 days (MR), 5 days (GR) and 21 days (5-HT1A). Hybridization controls included incubation of tissue with sense-strand constructs. No signal was detected in control tissue. Controls for MR and GR mRNA probes have been published previously (Herman et al., 1989).

Image analysis

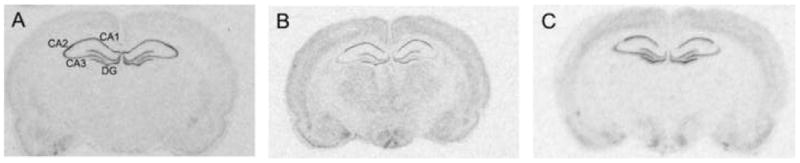

Autoradiograph films were semi-quantitatively analyzed using NIH Scion Image Software. The region of a section showing signal was delineated by the pattern of grain localization on the image. Anatomical regions of interest were determinated based on Paxinos and Watson’s rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2005). Measurements were taken from the subfields CA1, CA2, CA3 and dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampi. In all cases the mean value of three sections through a given region per brain, both left and right sides (six individual measurements per brain) was calculated for each animal and used in the statistical analysis. Background signal was sampled from the corpus collosum and subtracted from all regions. Thus, the final measurement represents corrected gray level measurements indicative of signal intensity. All in situ quantification was performed in a blind fashion, with person performing the measurements unaware of the group assignments.

Hormone assays

Corticosterone (CORT)

Total corticosterone (bound plus free) levels were measured by RIA (Kaneko et al., 1981) in plasma extracted in absolute ethanol (Weinberg and Bezio, 1987). Antiserum was obtained from MP Biomedicals (Orangeburg, NY, USA), tritiated corticosterone tracer from Mandel Scientific (Guelph, ON, Canada) and corticosterone for standards from Sigma Chemical Co (S. Louise, MO, USA). Dextran-treated charcoal (Fisher Scientific Ltd, Nepean, ON, Canada) was used to absorb free corticosterone after incubation. The antiserum cross-reacts 100% for corticosterone, 2.3% for desoxycorticosterone, 0.47% for testosterone, 0.17% for progesterone and 0.05% for aldosterone. The minimum detectible corticosterone concentration was 0.25 μg/dl and the intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 1.55% and 4.26%, respectively.

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)

Plasma ACTH concentrations were measured using the Diasorin ACTH RIA kit (Stillwater, MS, USA); all reagents and samples were halved. The minimum detectable amount of ACTH was 20 pg/ml and the intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 3.9% and 6.5% respectively. The antibody cross-reacts 100% with human ACTH 1–24, 100% with porcine ACTH 1–39 but not with calcitonin, FSH, parathyroid hormone, vasopressin or human growth hormone (<0.01%).

Estradiol (E2)

Plasma concentrations were detected using an adaptation of the Diagnostic Products Corporation Double Antibody E2 RIA kit (Los Angeles, CA, USA); all reagents and samples were halved. The minimum detectable amount of E2 was 5 pg/ml. The E2 antibody cross-reacts 100 % with Estradiol-17β, 12.5% with Estrone, 0.235% with Estriol but does not cross-react with progesterone, testosterone, the mineralcorticoids nor with the glucocorticoids (all <0.01%). The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 7.2 % and 8.9%, respectively.

Progesterone (P4)

Plasma levels were measured using an adaptation of progesterone RIA kit (ICN Biomedicals, Inc., Costa Mesa, CA, USA) with [125I] progesterone as tracer and all reagent volumes halved. The progesterone antibody cross-reacts 100% with progesterone, 5.41% with 20α-dihydroprogesterone, 3.8% with desoxycorticosterone, 0.7% with CORT, 0.16% with testosterone, but not with 17α-estradiol, 17β-estradiol, aldosterone, or cortisol (<0.01%). The minimum detectable progesterone concentration was 0.2 ng/ml, and the intra-and inter-assay coeffeicients of variation were 3.6% and 6.7% respectively.

Data analysis

Hormone data were analyzed by two way ANOVAs for the factors of group (E, PF, C) and stage of estrous cycle (diestrus, proestrus, estrus). Significant main effects and interactions were further analyzed by Fisher’s LSD post hoc tests.

Receptor data were analyzed by three way ANOVAs for the factors of group (E, PF, C), stage of estrous cycle (diestrus, proestrus, estrus) and hippocampal subfield (CA1, CA2, CA3, DG). Significant main effects and interactions were further analyzed by separate two way ANOVAs conducted for each phase of the estrous cycle followed by Fisher’s LSD post hoc tests. All data were analyzed using Statistica 6 software.

3. Results

3.1. BALs

The mean BAL for ethanol-consuming dams was 141.9 ± 12.5 mg/dl, measured ~2 hr after lights off, consistent with previous studies that have employed the same breeding and feeding protocols. It has been shown that BALs of this level induce biological and behavioral deficits in the offspring (Keiver and Weinberg, 2003; Weinberg, 1985).

3.2. Hormone levels as a function of estrous stage

(Note: The basal hormone data reported here were part of a larger study, and cited also in Lan et al., submitted).

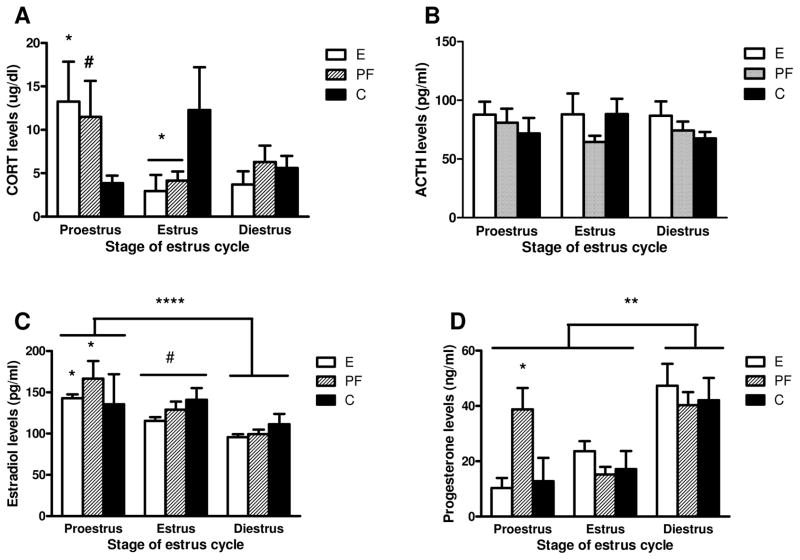

3.2.1. Basal CORT and ACTH levels across the estrous cycle

Analysis of basal CORT levels revealed a group x stage interaction F(4,60)=3.0526, p=0.02. Post-hoc analysis showed that during proestrus, CORT levels were higher in E than in C (p<0.05) females, and there was a trend for higher CORT in PF compared to C (p=0.07). In estrus, on the other hand, CORT levels were lower in both E and PF compared to C (p<0.05) females (Fig. 1A). In contrast to CORT, there were no significant effects of group or estrous cycle stage for ACTH, Fig. 1B.

Figure 1.

Basal plasma levels of corticosterone [CORT] (A), adrenocorticotropic hormone [ACTH] (B), estradiol (C) and progesterone (D) in adult females rats prenatally exposed to ethanol (E), pair-fed (PF) and controls (C). Data represents mean ±SEM of 4–22 rats per group. (A) in proestrus: E>C, * p<0.05 and PF>C, trend # p=0.07; in estrus: E=PF<C, * p<0.05; (B) there is no statistically significant differences across the estrous cycle among groups; (C) proestrus>diestrus, **** p<0.00001 and proestrus >estrus, trend # p=0.057; in proestrus PF>C, * p<0.05; for E females only: proestrus>diestrus, * p<0.01; (D) diestrus>estrus=proestrus, *** p<0.001; in proestrus: PF>E=C, * p<0.05.

3.2.2. Basal estradiol and progesterone levels across the estrous cycle

The 2-way ANOVA on basal E2 levels revealed a significant main effect of stage F(2,66)=15.920, p=0.00002. Overall, plasma E2 levels were higher in proestrus than in diestrus (p<0.00001), and there was a trend for higher E2 levels in proestrus compared to estrus, p=0.057, Fig. 1C. Additionally, C females showed similar basal E2 levels across the cycle, whereas E females had higher basal E2 levels in proestrus compared to diestrus (p<0.01), and PF females had higher E2 levels in proestrus compared both diestrus and estrus (ps<0.05). Furthermore, in proestrus, PF (p<0.05) had higher stress E2 levels than C females, and there was a similar trend for E compared to C females (E>C, p<0.09).

The two-way ANOVA on basal P4 levels revealed a main effect of stage F(2,63)=13.044, p=0.00002, and a trend for a group x stage interaction F(4,63)=2.2844, p=0.07. As expected, plasma P4 levels were significantly higher in diestrus than in proestrus and estrous (D>E=P, p <0.001). In addition, in proestrus, basal P4 levels were elevated specifically in PF females (PF>E=C, p<0.05), Fig. 1D.

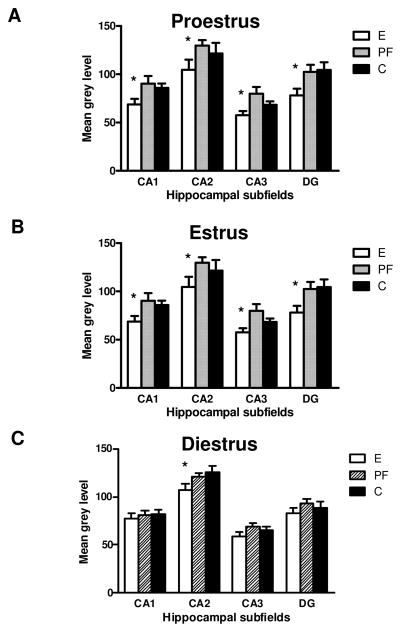

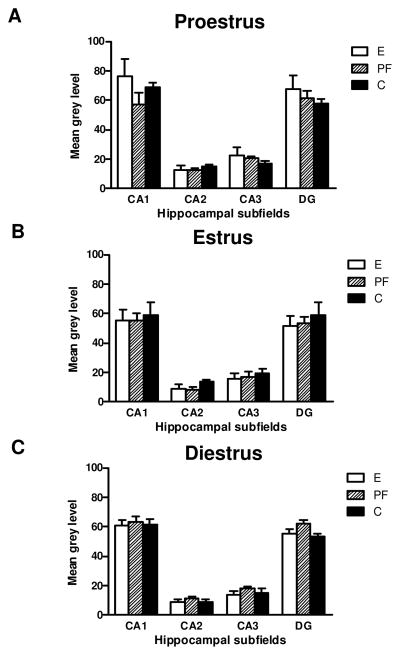

3.3. Alterations in hippocampal MR and GR mRNA levels across the estrous cycle

Figure 2A and B shows the distribution of hippocampal MR and GR mRNA. In agreement with previous findings (Herman et al., 1989), MR mRNA was expressed in a subfield-specific manner such that levels were highest in CA2, lowest in CA3, and intermediate in DG and CA1 (Figs. 2A and 3). GR mRNA levels were highest in CA1 and DG, intermediate in CA3 and lowest in CA2 (Fig. 2B and 4). Furthermore, consistent with previous findings (Herman et al., 1989), MR mRNA levels were considerably more abundant than GR mRNA in all subfields examined (Figs. 2A and B, 3 and 4).

Figure 2.

Autoradiograms represent the in situ hybridization signal within rat hippocampus in adult female rats for: (A) MR mRNA; (B) GR mRNA and (C) 5HT1A mRNA. Hippocampal subfields: CA1, CA2, CA3 and dentate gyrus - DG.

Figure 3.

MR mRNA in the hippocampal subfields (CA1, CA2, CA3 and DG) in adult female rats prenatally exposed to ethanol (E), pair-fed (PF) and controls (C) across the estrous cycle; (A) proestrus; (B) estrus and (C) diestrus. Data represents mean ±SEM of 4–12 brains per group. (A) in proestrus: E<PF=C in CA1, CA2 and DG, * p<0.05 and E<PF in CA3; (B) in estrus: E=PF<C in CA1, CA3 and DG, * p<0.05; (C) in diestrus E<PF=C in CA2, * p<0.05.

Figure 4.

GR mRNA in the hippocampal subfields (CA1, CA2, CA3 and DG) in adult female rats prenatally exposed to ethanol (E), pair-fed (PF) and controls (C) across the estrous cycle; (A) proestrus; (B) estrus and (C) diestrus. Data represents mean ±SEM of 4–12 brains per group. Only in E females GR mRNA levels were higher in proestrus then in estrus in diestrus (proestrus>estrus =diestrus), *p<0.05.

The 3-way ANOVA on MR mRNA levels revealed main effects of group, F(2,216)=14.038, p=0.00001, stage, F(2,216)=3.71121, p=0.026, and subfield, F(3,216)=91.813, p<0.00001, and a group x stage interaction, F(4,216)=4.7416, p=0.001. Overall, MR mRNA levels were higher in proestrus compared to diestrus and estrus (ps<0.05; Fig 3). Further group x subfield ANOVAs within each estrous stage then revealed main effects of group at all stages of the cycle [proestrus (F(2,48)=12.044, p=0.00006, Fig. 3A); estrous (F(2,52)=8.1496, p=0.00083, Fig. 3B); diestrus (F(2,116)=3.9600, p=0.02, Fig. 3C)]. During proestrus, MR mRNA levels were lower in E compared to both PF and C females in CA1, CA2 and the DG, and lower in E compared to PF females in CA3 (ps<0.05), while in diestrus, post hoc comparisons reached significance only in CA2 (E<PF=C, p<0.05). In estrus, MR mRNA levels were lower in both E and PF compared to C females in all subfields except CA2 (ps<0.01).

A 3-way ANOVA on GR mRNA levels revealed main effects of stage F(2,204)=4.7049, p=0.01) and subfield F(3,204)=302.74, p<0.00001, and a group x stage interaction F(4,204)=2.5412, p=0.04. Post hoc analysis revealed that in E females, GR mRNA levels were higher in proestrus than in estrous and diestrus (p’s<0.05), whereas PF and C females did not show estrus stage-specific changes in GR mRNA levels. Furthermore, a subfield effect was seen in all groups, with GR mRNA levels in CA1>DG>CA3>CA2, ps<0.05; Fig. 4.

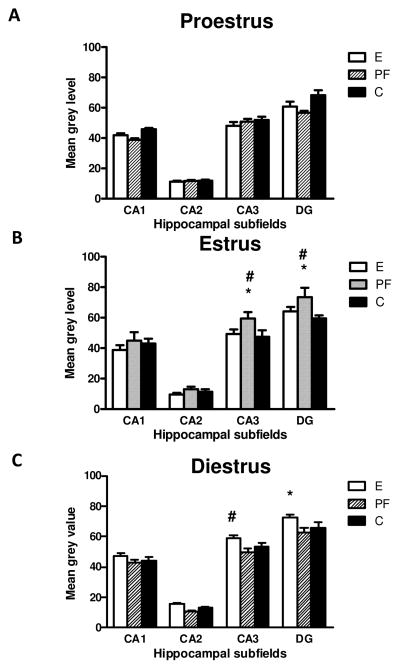

3.4. Alterations in hippocampal 5-HT1A mRNA levels across the estrous cycle

5-HT1A mRNA was present in all hippocampal subfields examined (Fig. 2C), with the greatest abundance in the DG, CA3 and CA1 and the lowest abundance in CA2 (Figs. 2C and 5), consistent with previous findings (Chalmers et al., 1993; Osterlund et al., 2000).

Figure 5.

5HT1A mRNA in the hippocampal subfields (CA1, CA2, CA3 and DG) in adult female rats prenatally exposed to ethanol (E), pair-fed (PF) and controls (C) across the estrous cycle. Data represents mean ± SEM of 4–12 brains per group. (B) estrus: in CA3 and DG: PF>C, *p<0.05 and PF>E, trend p=0.06; (C) in diestrus E>C=PF in CA3, trend # p=0.06 and E>C=PF in DG, * p<0.05.

The 3-way ANOVA on 5-HT1A mRNA levels indicated main effects of subfield, F(3,220) = 453.50, p<0.0001, and stage, F(2,220)= 3.9167, p=0.02, and a group by stage interaction (F(4,220)= 8.0327, p<0.00001; Fig. 5). Overall, 5-HT1A mRNA levels were highest in DG and lowest in CA2 (DG>CA3>CA1>CA2, p<0.05), and higher in diestrus than in both estrus and proestrus, p<0.05. Furthermore, analysis of each estrous stage revealed significant group differences. In diestrus (F(2,124)=11.714, p=0.00002, Fig. 5C), 5-HT1A mRNA levels were higher in E compared to PF and C females in the DG p<0.005, and there was a similar trend for CA3 (p=0.06). In contrast, a significant main effect of group for estrus (F(2,48)=5.58, p=0.00662, Fig. 5B) reflected a PF effect; 5-HT1A mRNA levels were higher in PF compared to E and C females in both CA3 (ps<0.05) and the DG (PF>C, p<0.05 and PF>E, p=0.06).

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of findings

The present study is the first to demonstrate long-lasting consequences of prenatal ethanol exposure for basal CORT regulation as well as for basal levels of hippocampal MR, GR and 5-HT1A mRNA as a function of estrous cycle stage in adult female rats. By examining changes in mRNA and hormone levels relative to estrous cycle stage, instead of collapsing data across the cycle, we were able to unmask novel and important information on the effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on the HPA activity and 5HT1A receptor levels. Overall, basal CORT levels were higher in E compared to C females in proestrus but lower in E and PF compared to C females in estrus. At the level of the hippocampus, there was an overall decrease in MR mRNA levels in E compared to PF and C females, with the greatest effects in proestrus, whereas E but not PF or C females had higher GR mRNA levels in proestrus than in estrous and diestrus. In addition, 5-HT1A mRNA levels were increased in E compared to PF and C females in diestrus. Whereas ethanol-induced changes in MR mRNA levels occurred in all hippocampal subfields, changes in 5HT1A mRNA levels reached statistical significance only in the CA3 and DG subfields. That alterations were revealed as a function of estrous cycle stage suggests a role for the ovarian steroids in mediating these effects. Furthermore, since some findings were similar in E and PF females, it appears that ethanol-induced nutritional effects may play a role in mediating the adverse effects of ethanol on outcomes studied here.

4.2. Prenatal ethanol alters basal levels of CORT but not basal levels of ACTH, E2 or P4in adult female rats across estrous cycle

In studies to date, including our own, HPA hormone levels have been measured primarily at the circadian trough, and typically without regard to estrous cycle stage (Kim et al., 1999; Lee and Rivier, 1996; Weinberg, 1988; 1992a). In the present report, by factoring in stage of estrous cycle, we unmasked differences in basal CORT among prenatal groups, and found that basal CORT levels varied as a function of prenatal treatment and estrous cycle stage. An increase in basal CORT was seen in E females in proestrus, with a similar trend in the PF group, whereas in estrus, E and PF females had lower basal CORT levels compared to their C counterparts. Interestingly, however, there were no statistically significant differences in CORT levels in control animals across the estrous cycle. Previous data suggest that stage differences in basal CORT levels do exist in control females, but may be detectable primarily at the circadian peak (Atkinson and Waddell, 1997; Carey et al., 1995). In the present study, we terminated animals in the morning, at the circadian trough, in order to obtain low basal CORT levels. Consistent with our data, Viau & Meaney (1991), Carey and colleagues (Carey et al., 1995), and Atkinson and Waddell (Atkinson and Waddell, 1997) reported no significant CORT differences across the estrous cycle when CORT was measured at the circadian trough. One exception to these findings is a study by Figueiredo and colleagues (Figueiredo et al., 2002) who found higher pre-stress plasma CORT but not ACTH levels in proestrus compared to estrous females sampled at the circadian trough.

Overall, these findings, together with our data showing differences in basal CORT levels in E and PF females but not C females across the estrous cycle, suggest differential HPA sensitivity to gonadal hormone fluctuations across the estrous cycle, and in particular, increased sensitivity to the stimulatory effects of estradiol, in E and PF compared to C females. Moreover, and consistent with our previous work (Glavas et al., 2007), it is possible that deficits in HPA feedback regulation in E females contribute to the altered HPA-HPG interactions and thus to altered basal CORT levels. In contrast to the CORT findings there were no effects of either prenatal treatment or estrous cycle stage on basal ACTH levels across the cycle. These data are in agreement with studies by other investigators (Atkinson and Waddell, 1997; Carey et al., 1995; Figueiredo et al., 2002; Viau and Meaney, 1991). On the other hand, we have recently shown (Lan et al., submitted) that stress levels of both CORT and ACTH levels are greater in E than in PF and/or C females in proestrus, supporting the suggestion that increased HPA sensitivity to the effects of estradiol may underlie HPA hyperresponsiveness to stressors in E females.

Our finding of an increase in basal CORT levels without an increase in ACTH levels is not entirely surprising. Although ACTH directly stimulates CORT release, changes in ACTH and CORT are not always directly proportional to each other. Indeed, the amount of CORT released was shown to be proportional to the logarithm of the ACTH concentration (Keller-Wood et al., 1983) and the CORT response to ACTH may be maximal at levels of ACTH that are in the lower 1/3 of the physiological range of ACTH (Keller-Wood et al., 1981). Furthermore, increasing levels of ACTH may not lead to further increases in CORT levels, although the duration of CORT release may be prolonged. In other words, very small changes in ACTH could lead to big changes in CORT levels, and it is not unusual for there to be some dissociation between CORT and ACTH. This could be the case in our study.

While we did not find prenatal treatment effects on basal estradiol or progesterone levels across the estrous cycle, we did see overall variations in hormone levels as a function of cycle stage. In agreement with data of Figueiredo and collaborators (Figueiredo et al., 2002), we found that under basal conditions, estradiol levels were higher overall in proestrus then in diestrus, and there was the same trend for proestrus compared to estrous. In addition, we found that progesterone levels were significantly higher in diestrus than in proestrus and estrus. Typically, progesterone levels peak in the morning of diestrus and in the afternoon proestrus (Nequin et al., 1979; Smith et al., 1975). As animals in the present study were tested in the morning, at the circadian trough, the lack of elevated progesterone levels in proestrus (Fig. 1D) is most likely due to the time of sampling. Figueiredo and coworkers (Figueiredo et al., 2002) have reported similar results. Moreover, the fact that animals were sampled in the morning could account for the fact that proestrus estradiol levels, while significantly higher than levels in estrus and diestrus, were not as high as expected. It is likely that the morning sampling time meant that animals in this study were in very early proestrus.

In addition to the effects of prenatal ethanol exposure, we found that pair-feeding in itself altered progesterone levels. That is, PF females in proestrus had higher progesterone levels than C and E females. This pair-feeding effect may be due to the fact that pair-feeding is a treatment as well as a control. Pair-fed dams are fed a reduced ration and therefore are hungry and experience a mild level of stress superimposed on mild undernutrition. Importantly, like prenatal ethanol exposure, both prenatal stress and prenatal undernutrition can program the HPA axis, altering HPA tone and stress responsiveness as well as circadian activity (Kehoe et al., 2001). Thus, it is possible that the stress of pair-feeding or the mild underfeeding of the PF dams may cause a subtle shift circadian rhythms in PF females such that at the time of sampling they were in late proestrus, whereas E and C females were in early proestrus, thus accounting for the differential hormone levels observed.

4.3. Prenatal ethanol alters MR and GR mRNA levels in female rats across the estrous cycle

4.3.1. Regulation of MR and GR by estrogen and progesterone

Consistent with previous findings in male guinea pig offspring prenatally exposed to ethanol (Iqbal et al., 2005), the present data demonstrate a downregulation in MR mRNA levels in ethanol-exposed female rats. Importantly, this downregulation was estrous cycle stage-dependent, being most pronounced in proestrus, when levels of estradiol are high, and least pronounced in diestrus, when estradiol levels are low. While these findings suggest a role for the sex steroids in the regulation of MR mRNA expression in E animals, there are contradictory findings in the literature concerning the regulation of MR by ovarian steroids. Following estrogen exposure, both increases (Ferrini and De Nicola, 1991) and decreases (Carey et al., 1995) in hippocampal MR binding capacity, as well as downregulation of hippocampal MR expression (Castren et al., 1995) have been observed. In contrast, Burgess and Handa, using a longer estradiol exposure paradigm (21 day replacement), found no effect of estrogen on binding parameters of hippocampal MR (Burgess and Handa, 1992). These studies suggest that estrogen dose and length of exposure may be significant factors in the outcome observed. In the present study, it is unlikely that estradiol alone mediated the observed alterations in MR mRNA, as there were no statistically significant differences in estradiol levels in E compared to C females at any stage of the estrous cycle. Consistent with this, our recent unpublished results (Sliwowska et al., in preparation) with a long (2 week) estradiol replacement regimen showed that more prolonged exposure to either low or high basal levels of estradiol did not induce changes in MR mRNA expression. In contrast to the effects of estradiol, data suggest that progesterone alone has no effect on hippocampal MR mRNA expression (Castren et al., 1995), but when given to estrogen-primed OVX (Carey et al., 1995) or OVX/ADX animals (Castren et al., 1995), progesterone can reverse the estradiol-induced decrease in hippocampal MR binding capacity, induce an increase in hippocampal MR binding affinity, and increase MR mRNA levels. In view of these findings, it is possible that the elevated progesterone levels observed in diestrus attenuated the effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on MR mRNA expression.

In contrast to the MR mRNA data, and in agreement with findings of Iqbal and collaborators (Iqbal et al., 2005), we did not find specific changes in GR mRNA expression as a function of estrous cycle. However, we found that E but not PF and C females had higher GR mRNA levels in proestrus than in estrus and diestrus. A previous study reported that neither estrogen nor progesterone treatment affected GR binding in the hippocampus (Carey et al., 1995). Moreover, progesterone alone had little or no effect on the GR transcript, but was shown to modulate the effects exerted by estrogen (Patchev and Almeida, 1996; Redei et al., 1994). Furthermore, physiological doses of estrogen given to ovariectomized rats decreased hippocampal GR mRNA after 3 weeks (Burgess and Handa, 1993), whereas a shorter (1 week) exposure period increased hypothalamic GR mRNA (Redei et al., 1994). Thus, it appears that downergulation of the GR transcript is observed with prolonged but not with short-term estradiol and/or progesterone exposure regimens. It is possible that in the present study, while relatively quick fluctuation in sex steroids across the estrus cycle were not able to alter GR mRNA expression, overall, E females were more sensitive than PF and C females to these normal hormonal fluctuations.

4.3.2. Regulation of MR and GR by corticosterone

It is well established that GR expression is negatively regulated by endogenous corticosteroids. Hippocampal GR is upregulated at both the binding and mRNA levels by adrenalectomy (Herman et al., 1989; Reul et al., 1989; Tornello et al., 1982), and stress and high-dose glucocorticoid treatment appear to downregulate hippocampal GR binding (Sapolsky et al., 1984; Sapolsky and McEwen, 1985). On the other hand the regulation of MR expression is less well understood. A limitation of the binding studies is the necessity to adrenalectomize animals in order to measure total receptor level, which precludes measurement of the ligand-activated form of MR (Kalman and Spencer, 2002). Furthermore, the stress related to surgery as well as the removal of endogenous corticosteroids could themselves alter MR protein expression. Nevertheless, an alternative approach, Western blot on whole-cell extracts from hippocampus, showed that MR protein is negatively regulated by adrenal steroids (Kalman and Spencer, 2002).

Only a few previous studies have examined the effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on MR and GR regulation. In the guinea pig, prenatal ethanol exposure was shown to increase hippocampal GR mRNA in near term males (Iqbal et al., 2006), but this effect did not persist into adulthood (Iqbal et al., 2005). In contrast, hippocampal MR mRNA expression was decreased in fetal ethanol-exposed adult male offspring compared to controls (Iqbal et al., 2005). In addition, work from our lab (Glavas et al., 2007) found that E females showed a greater MR mRNA response, and E males showed a greater GR mRNA response to ADX than their C counterparts, and that CORT replacement was ineffective in normalizing ADX-induced alterations in hippocampal MR mRNA levels in E males, but not females, suggesting that HPA dysregulation in E animals reflects both increased HPA drive and deficits in feedback regulation. Furthermore, prenatal ethanol exposure may have differential effects on male and female offspring.

In the present study, it is unlikely that CORT alone is responsible for MR mRNA downregulation in E and PF females, since downregulation was observed not only during proestrus when basal CORT levels were higher, but also during estrus when CORT levels were lower in E and PF compared to C females. On the other hand, an interaction of CORT and the sex steroids may be important in the differences observed between E and control females. For example, estrogen was shown to exert inhibitory influences on hippocampal GR mRNA but only in the presence of corticosterone (Patchev and Almeida, 1996).

Importantly, our data demonstrate for the first time that adult animals prenatally exposed to ethanol have an altered hippocampal MR/GR mRNA balance. As noted in the Introduction, a balance in MR- and GR-mediated actions is important for maintenance of adaptation, health and homeostasis (De Kloet et al., 1998). Thus, we postulate that the altered MR/GR imbalance reported here could contribute to the hyperactivity and increased vulnerability to diseases such as depression that have been reported following prenatal ethanol exposure (see below section 4.5). Data have shown that the hippocampus both tonically inhibits HPA tone and contributes to the negative feedback suppression of stress-initiated activity (Jacobson and Sapolsky, 1991; Reul and de Kloet, 1985). In support of this, several studies have shown that damage to the hippocampus increases basal glucocorticoid secretion (Fendler et al., 1961; Fischette et al., 1980; Herman et al., 1989; Sapolsky et al., 1984; Wilson et al., 1980). However, Tuvnes and collaborators found that complete axon-sparing lesions of the hippocampus did not increase CORT concentrations in rats (Tuvnes et al., 2003). While our studies do not directly address this question, they support a role for the hippocampus in regulation of basal HPA activity in animals prenatally exposed to ethanol.

4.4. 5-HT1A receptor mRNA expression is altered in animals prenatally exposed to ethanol: Possible role of sex-steroids and corticosterone

The present data are the first to show changes in 5-HT1A mRNA across the estrous cycle in adult females prenatally exposed to ethanol. We found that group differences in the pattern of 5-HT1A mRNA expression were dependent on estrous cycle stage. 5-HT1A mRNA levels were higher in E compared to PF and C females in the DG and CA3 subfields during diestrus, whereas in estrus, there was a significant PF effect, with higher 5-HT1A levels in PF compared to E and C females in both CA3 and the DG.

Serotonergic cell bodies are located in the brain stem and project to the hippocampus, (Oleskevich and Descarries, 1990). This indicates a strong modulatory influence on hippocampal function, where 5-HT1A is the most prominent 5-HT receptor present (Chalmers et al., 1993). Data have shown that prenatal ethanol exposure results in development of fewer 5-HT neurons and a lower density of 5-HT fibers in the dorsal raphe (Sari and Zhou, 2004; Zhou et al., 2005; Zhou et al., 2001). Importantly, prenatal administration of 5-HT1A agonists to pregnant dams has been shown to ameliorate some of the serotonergic deficits resulting from prenatal ethanol exposure in offspring (Tajuddin and Druse, 1993; 2001). The present data extend these findings by demonstrating prenatal ethanol effects on 5-HT1A receptor mRNA expression.

Estrogen also causes alterations in 5-HT1A mRNA that are both brain region specific and dependant on the pattern of estradiol exposure. Flugge et al (1999) found that in proestrus and estrus, and in OVX females replaced with estrus levels of estradiol, 5-HT1A binding in the the ventromedial hypothalamus was higher than in their OVX counterparts, whereas there was no change in the binding parameters in the hippocampus (Flugge et al., 1999). These data suggest that regulatory effects of estradiol on 5-HT1A receptor expression probably do not occur at the level of the hippocampus. Thus, changes observed by us in 5-HT1A mRNA expression could be due to changes in CORT levels among groups during the estrous cycle. Corticocosteroids may act directly on serotonergic neurotransmission by regulating 5-HT receptors. Several investigators have reported an increase in 5-HT1A gene expression and receptor binding in rat hippocampus in response to ADX (Burnet et al., 1996; Chalmers et al., 1993; Chalmers et al., 1994), while administration of low dose CORT at the time of ADX maintained 5-HT1A levels within the range of Sham animals (Chalmers et al., 1993). These data indicate that 5-HT1A is under tonic inhibition by corticosterone. Thus in our model, in estrus, high levels of CORT in C compared to E and PF could downregulate 5-HT1A mRNA in C females. On the other hand, low levels of CORT in diestrus were not able to downregulate 5-HT1A mRNA in any group of animals. Rather we found upregulation of 5-HT1A mRNA in the DG and a similar trend in CA3 in E compared to PF and C animals. This upregulation could reflect decreased numbers of serotonergic neurons typically found in animals prenatally exposed to ethanol, as discussed earlier (Sari and Zhou, 2004; Tajuddin and Druse, 1999; Zhou et al., 2005; Zhou et al., 2001). Similarly, studies by Lopez and collaborators (Lopez et al., 1998) showed that exposure to a repeated mild stressor did not cause significant decreases in hippocampal 5-HT1A mRNA or 5-HT1A binding compared to control (non-stressed) animals.

4.5. Prenatal stress, prenatal alcohol exposure and dysregulation of HPA and serotenergic systems in adulthood: Implications for the neurobiology of depression

Among their problems, both children and adults with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) have higher rates of mental health disorders, including depression, compared to the normal population (Famy et al., 1998; O’Connor and Paley, 2006; Streissguth et al., 1996). Altered function of the HPA and serotonergic systems is known to be critically involved in the etiology of depression (Lopez et al., 1998; Nestler et al., 2002; Pryce et al., 2005). In our rat model of prenatal ethanol exposure, offspring in adulthood share hormonal changes characteristic of depression: HPA hyperactivity, increased HPA drive, deficits in HPA feedback regulation, earlier escape from dexamethasone suppression, increased ACTH responsiveness to dexamethasone plus CRH, alterations in the serotonergic system [see reviews: (Sliwowska et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2005)]. Similar changes have been reported following prenatal stress (Fameli et al., 1994; Ishiwata et al., 2005; Kehoe et al., 2001; Viltart et al., 2006). Moreover, studies by Lopez and collaborators (Lopez et al., 1998) showed that rats subjected to chronic unpredictable stress in adulthood exhibit elevations of basal plasma CORT, decreases in 5-HT1A mRNA and binding in the hippocampus, lower MR mRNA levels, and alterations in the MR/GR ratio. Interestingly, these changes were prevented by antidepressant treatment with serotonin reuptake inhibitors (imipramine or desipramine), possibly by decreasing stress-induced corticosteroid elevations. Consistent with the animals studies, suicide victims with a history of major depression tend to have lower MR mRNA levels, decreased 5-HT1A and no change in GR mRNA levels, suggesting a possible mechanism by which stress can trigger and/or maintain depressive episodes (Lopez et al., 1998).

In our study, a shift in the MR/GR balance was most marked in E females in proestrus. This could mediate an increase in basal CORT levels, impaired negative feedback inhibition of HPA activity, and hyperresponsiveness to stressors. That these changes were manifested in proestrus, when E2 levels are high, we postulate that E females may have increased sensitivity to estradiol, which in turn could enhance CORT release. Furthermore, in light of the relationship between depression in adulthood and adverse early life events (Gutman and Nemeroff, 2003) we propose that prenatal ethanol exposure can be viewed as an early life stressor that sensitizes or primes neurobiological stress systems (Holsboer, 2000), making them hyperactive in response to subsequent, even mild, stressful life events, and ultimately, increasing the vulnerability to depression and other stress-related disorders. Indeed, Olson and collaborators (Olsen et al., 1998) describe the impact of postnatal factors on the development of secondary disabilities and psychiatric conditions in children with FASD. They suggest that problems emerge when alcohol-exposed individuals, who are constitutionally vulnerable, are exposed to sufficient levels and/or types of stressors, which then mediates poor outcome. Additionally animals prenatally exposed to ethanol have numerous dysfunctions of the serotenergic system, as discussed above, as well as alterations in 5HT1A receptor mRNA reported here, which together could disrupt interactions between the HPA and 5-HT systems, and in turn, underlie, at least in part, the increased vulnerability to depression seen in children with FASD. Current studies in our laboratory to investigate changes in MR, GR and 5HT receptors under chronic stress conditions should give us a better understanding of how and where interactions between these systems is altered.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Linda Ellis and Wayne Yu for expert assistance in all phases of the research, and James Choi and Paxton Bach for expert help with this study. Funding for this study was provided by NIH Grant AA007789 to J.W. and V.V., grants from the BC Ministry of Children and Family Development (through the UBC Human Early Learning Partnership) and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research to J.W., a Bluma Tischler Fellowship and an IMPART Fellowship (CIHR training grant) to J.H.S. and NSERC Studentship to N.L.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andrews MH, Matthews SG. Programming of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis: serotonergic involvement. Stress. 2004;7:15. doi: 10.1080/10253890310001650277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson HC, Waddell BJ. Circadian variation in basal plasma corticosterone and adrenocorticotropin in the rat: sexual dimorphism and changes across the estrous cycle. Endocrinology. 1997;138:3842. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.9.5395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker JM, van Bel F, Heijnen CJ. Neonatal glucocorticoids and the developing brain: short-term treatment with life-long consequences? Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:649. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01948-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess L, Handa R. Estrogen-induced alterations in the regulation of mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptor messenger RNA experssion in female rat anterior pituitary and brain. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1993;4:191. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1993.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess LH, Handa RJ. Chronic estrogen-induced alterations in adrenocorticotropin and corticosterone secretion, and glucocorticoid receptor-mediated functions in female rats. Endocrinology. 1992;131:1261. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.3.1324155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnet PW, Mefford IN, Smith CC, Gold PW, Sternberg EM. Hippocampal 5-HT1A receptor binding site densities, 5-HT1A receptor messenger ribonucleic acid abundance and serotonin levels parallel the activity of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in rats. Behav Brain Res. 1996;73:365. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(96)00116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Deterd CH, de Koning J, Helmerhorst F, de Kloet ER. The influence of ovarian steroids on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal regulation in the female rat. J Endocrinol. 1995;144:311. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1440311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castren M, Patchev VK, Almeida OF, Holsboer F, Trapp T, Castren E. Regulation of rat mineralocorticoid receptor expression in neurons by progesterone. Endocrinology. 1995;136:3800. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.9.7649087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers DT, Kwak SP, Mansour A, Akil H, Watson SJ. Corticosteroids regulate brain hippocampal 5-HT1A receptor mRNA expression. J Neurosci. 1993;13:914. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-00914.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers DT, Lopez JF, Vazquez DM, Akil H, Watson SJ. Regulation of hippocampal 5-HT1A receptor gene expression by dexamethasone. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1994;10:215. doi: 10.1038/npp.1994.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaouloff F. Physiopharmacological interactions between stress hormones and central serotonergic systems. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1993;18:1. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90005-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaouloff F. Regulation of 5-HT receptors by corticosteroids: where do we stand? Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1995;9:219. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1995.tb00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Zhang L, Rubinow DR, Chuang DM. Chronic buspirone treatment differentially regulates 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptor mRNA and binding sites in various regions of the rat hippocampus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1995;32:348. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00098-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet ER, Joels M, Holsboer F. Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:463. doi: 10.1038/nrn1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet ER, Reul JM, Sutanto W. Corticosteroids and the brain. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1990;37:387. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(90)90489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kloet ER, Vreugdenhil E, Oitzl MS, Joels M. Brain corticosteroid receptor balance in health and disease. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:269. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.3.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre LF. Buspirone in the management of major depression: a placebo-controlled comparison. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51(Suppl):55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fameli M, Kitraki E, Stylianopoulou F. Effects of hyperactivity of the maternal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis during pregnancy on the development of the HPA axis and brain monoamines of the offspring. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1994;12:651. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(94)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Famy C, Streissguth AP, Unis AS. Mental illness in adults with fetal alcohol syndrome or fetal alcohol effects. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:552. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.4.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendler K, Karmos G, Telegdy G. The effect of hippocampal lesion on pituitary-adrenal function. Acta Physiol Acad Sci Hung. 1961;20:293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrini M, De Nicola AF. Estrogens up-regulate type I and type II glucocorticoid receptors in brain regions from ovariectomized rats. Life Sci. 1991;48:2593. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90617-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo HF, Dolgas CM, Herman JP. Stress activation of cortex and hippocampus is modulated by sex and stage of estrus. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2534. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.7.8888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischette CT, Komisaruk BR, Edinger HM, Feder HH, Siegel A. Differential fornix ablations and the circadian rhythmicity of adrenal corticosteroid secretion. Brain Res. 1980;195:373. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flugge G, Kramer M, Rensing S, Fuchs E. 5HT1A-receptors and behaviour under chronic stress: selective counteraction by testosterone. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:2685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flugge G, Pfender D, Rudolph S, Jarry H, Fuchs E. 5HT1A-receptor binding in the brain of cyclic and ovariectomized female rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 1999;11:243. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo PV, Weinberg J. Corticosterone rhythmicity in the rat: interactive effects of dietary restriction and schedule of feeding. J Nutr. 1981;111:208. doi: 10.1093/jn/111.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glavas MM, Ellis L, Yu WK, Weinberg J. Effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on basal limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal regulation: role of corticosterone. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1598. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glavas MM, Yu WK, Weinberg J. Effects of mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptor blockade on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function in female rats prenatally exposed to ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1916. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman DA, Nemeroff CB. Persistent central nervous system effects of an adverse early environment: clinical and preclinical studies. Physiol Behav. 2003;79:471. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa RJ, Burgess LH, Kerr JE, O’Keefe JA. Gonadal steroid hormone receptors and sex differences in the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Horm Behav. 1994;28:464. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1994.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, Patel PD, Akil H, Watson SJ. Localization and regulation of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptor messenger RNAs in the hippocampal formation of the rat. Mol Endocrinol. 1989;3:1886. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-11-1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann CE, Ellis L, Yu WK, Weinberg J. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A/C agonists are differentially altered in female and male rats prenatally exposed to ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:345. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann CE, Patyk IA, Weinberg J. Prenatal ethanol exposure: sex differences in anxiety and anxiolytic response to a 5-HT1A agonist. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;82:549. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsboer F. The corticosteroid receptor hypothesis of depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:477. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal U, Brien JF, Banjanin S, Andrews MH, Matthews SG, Reynolds JN. Chronic prenatal ethanol exposure alters glucocorticoid signalling in the hippocampus of the postnatal Guinea pig. J Neuroendocrinol. 2005;17:600. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal U, Brien JF, Kapoor A, Matthews SG, Reynolds JN. Chronic prenatal ethanol exposure increases glucocorticoid-induced glutamate release in the hippocampus of the near-term foetal guinea pig. J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18:826. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwata H, Shiga T, Okado N. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment of early postnatal mice reverses their prenatal stress-induced brain dysfunction. Neuroscience. 2005;133:893. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson L, Sapolsky R. The role of the hippocampus in feedback regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Endocr Rev. 1991;12:118. doi: 10.1210/edrv-12-2-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joels M, Van Riel E. Mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptor-mediated effects on serotonergic transmission in health and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1032:301. doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalman BA, Spencer RL. Rapid corticosteroid-dependent regulation of mineralocorticoid receptor protein expression in rat brain. Endocrinology. 2002;143:4184. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko M, Kaneko K, Shinsako J, Dallman MF. Adrenal sensitivity to adrenocorticotropin varies diurnally. Endocrinology. 1981;109:70. doi: 10.1210/endo-109-1-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe P, Mallinson K, Bronzino J, McCormick CM. Effects of prenatal protein malnutrition and neonatal stress on CNS responsiveness. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2001;132:23. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiver K, Weinberg J. Effect of duration of alcohol consumption on calcium and bone metabolism during pregnancy in the rat. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1507. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000086063.71754.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller-Wood ME, Shinsako J, Dallman MF. Integral as well as proportional adrenal responses to ACTH. Am J Physiol. 1983;245:R53. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1983.245.1.R53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller-Wood ME, Shinsako J, Keil LC, Dallman MF. Insulin-induced hypoglycemia in conscious dogs. I. Dose-related pituitary and adrenal responses. Endocrinology. 1981;109:818. doi: 10.1210/endo-109-3-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CK, Osborn JA, Weinberg J. Stress reactivity in fetal alcohol syndrome. In: Abel E, editor. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: From Mechanism to Behavior. CRC Press; 1996. p. 215. [Google Scholar]

- Kim CK, Turnbull AV, Lee SY, Rivier CL. Effects of prenatal exposure to alcohol on the release of adenocorticotropic hormone, corticosterone, and proinflammatory cytokines. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda Y, Watanabe Y, Albeck DS, Hastings NB, McEwen BS. Effects of adrenalectomy and type I or type II glucocorticoid receptor activation on 5-HT1A and 5-HT2 receptor binding and 5-HT transporter mRNA expression in rat brain. Brain Res. 1994;648:157. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91916-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan N, Yamashita F, Halpert AG, Ellis L, Yu WK, Viau V, Weinberg J. Prenatal ethanol exposure alters the effects of gonadectomy on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity in male rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18:672. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan N, Yamashita F, Halpert AG, Sliwowska JH, Ellis L, Yu W, Viau V, Weinberg J. Effect of prenatal ethanol exposure on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function across the rat estrous cycle. Psychoneuroendocrinology submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Imaki T, Vale W, Rivier C. Effect of prenatal exposure to ethanol on the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis of the offspring: Importance of the time of exposure to ethanol and possible modulating mechanisms. Molecular Cell Neuroscience. 1990;1:168. doi: 10.1016/1044-7431(90)90022-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Rivier C. Gender differences in the effect of prenatal alcohol exposure on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to immune signals. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21:145. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Schmidt D, Tilders F, Rivier C. Increased activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis of rats exposed to alcohol in utero: role of altered pituitary and hypothalamic function. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;16:515. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez JF, Chalmers DT, Little KY, Watson SJ. A.E. Bennett Research Award. Regulation of serotonin1A, glucocorticoid, and mineralocorticoid receptor in rat and human hippocampus: implications for the neurobiology of depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;43:547. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00484-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry CA. Functional subsets of serotonergic neurones: implications for control of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. J Neuroendocrinol. 2002;14:911. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2002.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcondes FK, Bianchi FJ, Tanno AP. Determination of the estrous cycle phases of rats: some helpful considerations. Braz J Biol. 2002;62:609. doi: 10.1590/s1519-69842002000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews SG. Early programming of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:373. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(02)00690-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer OC, de Kloet ER. Corticosterone suppresses the expression of 5-HT1A receptor mRNA in rat dentate gyrus. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;266:255. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(94)90134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson SD, McEwen BS. Autoradiographic analyses of the effects of adrenalectomy and corticosterone on 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors in the dorsal hippocampus and cortex of the rat. Neuroendocrinology. 1992;55:444. doi: 10.1159/000126160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto M, Morita N, Ozawa H, Yokoyama K, Kawata M. Distribution of glucocorticoid receptor immunoreactivity and mRNA in the rat brain: an immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization study. Neurosci Res. 1996;26:235. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(96)01105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LR, Taylor AN, Lewis JW, Poland RE, Redei E, Branch BJ. Pituitary-adrenal responses to morphine and footshock stress are enhanced following prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1986;10:397. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1986.tb05112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nequin LG, Alvarez J, Schwartz NB. Measurement of serum steroid and gonadotropin levels and uterine and ovarian variables throughout 4 day and 5 day estrous cycles in the rat. Biol Reprod. 1979;20:659. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod20.3.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Barrot M, DiLeone RJ, Eisch AJ, Gold SJ, Monteggia LM. Neurobiology of depression. Neuron. 2002;34:13. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00653-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor MJ, Paley B. The relationship of prenatal alcohol exposure and the postnatal environment to child depressive symptoms. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31:50. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleskevich S, Descarries L. Quantified distribution of the serotonin innervation in adult rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1990;34:19. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90301-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen H, Morse B, Huffine C. Development and Psychopathology: Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Related Conditions. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 1998;3:262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund MK, Halldin C, Hurd YL. Effects of chronic 17beta-estradiol treatment on the serotonin 5-HT(1A) receptor mRNA and binding levels in the rat brain. Synapse. 2000;35:39. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(200001)35:1<39::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patchev VK, Almeida OF. Gonadal steroids exert facilitating and “buffering” effects on glucocorticoid-mediated transcriptional regulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone and corticosteroid receptor genes in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7077. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-07077.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson SJ. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Elsevier Academic Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pryce CR, Ruedi-Bettschen D, Dettling AC, Weston A, Russig H, Ferger B, Feldon J. Long-term effects of early-life environmental manipulations in rodents and primates: Potential animal models in depression research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:649. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redei E, Li L, Halasz I, McGivern RF, Aird F. Fast glucocorticoid feedback inhibition of ACTH secretion in the ovariectomized rat: effect of chronic estrogen and progesterone. Neuroendocrinology. 1994;60:113. doi: 10.1159/000126741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reul JM, de Kloet ER. Two receptor systems for corticosterone in rat brain: microdistribution and differential occupation. Endocrinology. 1985;117:2505. doi: 10.1210/endo-117-6-2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reul JM, Pearce PT, Funder JW, Krozowski ZS. Type I and type II corticosteroid receptor gene expression in the rat: effect of adrenalectomy and dexamethasone administration. Mol Endocrinol. 1989;3:1674. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-10-1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reul JM, van den Bosch FR, de Kloet ER. Relative occupation of type-I and type-II corticosteroid receptors in rat brain following stress and dexamethasone treatment: functional implications. J Endocrinol. 1987;115:459. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1150459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DS, Rickels K, Feighner J, Fabre LF, Jr, Gammans RE, Shrotriya RC, Alms DR, Andary JJ, Messina ME. Clinical effects of the 5-HT1A partial agonists in depression: a composite analysis of buspirone in the treatment of depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10:67S. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199006001-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM, Krey LC, McEwen BS. Stress down-regulates corticosterone receptors in a site-specific manner in the brain. Endocrinology. 1984;114:287. doi: 10.1210/endo-114-1-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM, McEwen BS. Down-regulation of neural corticosterone receptors by corticosterone and dexamethasone. Brain Res. 1985;339:161. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90638-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sari Y, Zhou FC. Prenatal alcohol exposure causes long-term serotonin neuron deficit in mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:941. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128228.08472.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliwowska JH, Zhang X, Weinberger J. Prenatal Ethanol Exposure and Fetal Programming: Implication for Endocrine and Immune Developmant and Long-Term Health. In: Miller MW, editor. Brain Development. Normal Processes and The Effects of Alcohol and Nicotine. Oxford University Press; 2006. p. 153. [Google Scholar]

- Smith MS, Freeman ME, Neill JD. The control of progesterone secretion during the estrous cycle and early pseudopregnancy in the rat: prolactin, gonadotropin and steroid levels associated with rescue of the corpus luteum of pseudopregnancy. Endocrinology. 1975;96:219. doi: 10.1210/endo-96-1-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Barr HM, Kogan J, Bookstein FL. Undersatanding the Occurance of Secondary Disabilities in Clients with FAS and FAE. Report CDCP. Executive Summary. 1996:4. [Google Scholar]

- Tajuddin NF, Druse MJ. Treatment of pregnant alcohol-consuming rats with buspirone: effects on serotonin and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid content in offspring. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:110. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajuddin NF, Druse MJ. In utero ethanol exposure decreased the density of serotonin neurons. Maternal ipsapirone treatment exerted a protective effect. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;117:91. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajuddin NF, Druse MJ. A persistent deficit of serotonin neurons in the offspring of ethanol-fed dams: protective effects of maternal ipsapirone treatment. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2001;129:181. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AN, Branch BJ, Van Zuylen JE, Redei E. Maternal alcohol consumption and stress responsiveness in offspring. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1988;245:311. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-2064-5_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AN, Nelson LR, Branch BJ, Kokka N, Poland RE. Altered stress responsiveness in adult rats exposed to ethanol in utero: neuroendocrine mechanisms. Ciba Found Symp. 1984;105:47. doi: 10.1002/9780470720868.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornello S, Orti E, De Nicola AF, Rainbow TC, McEwen BS. Regulation of glucocorticoid receptors in brain by corticosterone treatment of adrenalectomized rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1982;35:411. doi: 10.1159/000123429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuvnes FA, Steffenach HA, Murison R, Moser MB, Moser EI. Selective hippocampal lesions do not increase adrenocortical activity. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4345. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04345.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eekelen JA, Jiang W, De Kloet ER, Bohn MC. Distribution of the mineralocorticoid and the glucocorticoid receptor mRNAs in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci Res. 1988;21:88. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490210113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viau V, Meaney MJ. Variations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to stress during the estrous cycle in the rat. Endocrinology. 1991;129:2503. doi: 10.1210/endo-129-5-2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viltart O, Mairesse J, Darnaudery M, Louvart H, Vanbesien-Mailliot C, Catalani A, Maccari S. Prenatal stress alters Fos protein expression in hippocampus and locus coeruleus stress-related brain structures. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:769. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J. Effects of ethanol and maternal nutritional status on fetal development. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1985;9:49. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1985.tb05049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J. Hyperresponsiveness to stress: differential effects of prenatal ethanol on males and females. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1988;12:647. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J. Prenatal ethanol exposure alters adrenocortical development of offspring. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1989;13:73. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1989.tb00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J. Prenatal ethanol effects: sex differences in offspring stress responsiveness. Alcohol. 1992a;9:219. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(92)90057-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J. Neuroendocrine effects of prenatal alcohol exposure. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993b;697:86. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb49925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J, Bezio S. Alcohol-induced changes in pituitary-adrenal activity during pregnancy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1987;11:274. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1987.tb01307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J, Sliwowska JH, Lan N, Hellemans KG. Prenatal alcohol exposure: foetal programming, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and sex differences in outcome. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:470. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welberg LA, Seckl JR. Prenatal stress, glucocorticoids and the programming of the brain. J Neuroendocrinol. 2001;13:113. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2001.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MM, Greer SE, Greer MA, Roberts L. Hippocampal inhibition of pituitary-adrenocortical function in female rats. Brain Res. 1980;197:433. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita F, Lan N, Yu W, Ellis L, HAG, Weinberg J. Role of estradiol in stress hyperresponsiveness seen in female rats preanatally exposed to ethanol. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2004;26:502. [Google Scholar]