Abstract

The bottom-up construction of cell-sized compartments programmed with DNA that are capable of sensing the chemical and physical environment remains challenging in synthetic cell engineering. Here, we construct mechanosensitive liposomes with biosensing capability by expressing the E. coli channel MscL and a calcium biosensor using cell-free expression.

Cell-free expression (CFE) has been recently reshaped into a highly versatile technology applicable to an increasing number of research areas1. The new generation of DNA-dependent cell-free transcription-translation systems (TXTL) has been engineered to address applications over a broad spectrum of engineering and fundamental disciplines, from synthetic biology to biophysics and chemistry2–4. Modern TXTL platforms are used for medicine and biomolecular manufacturing, such as the production of vaccine and therapeutics5, 6. By performing non-natural chemistries3, 7, 8, the TXTL technology has been improved to expand the molecular repertoire of biological systems. Because the time for design-build-test cycle is dramatically reduced, TXTL has become a powerful platform to rapidly prototype genetic programs in vitro, from testing single regulatory elements to recapitulating metabolic pathways9. Remarkably, the new TXTL systems have also been prepared so as to work at many different scales and in different experimental settings. As such, TXTL reactions can be carried out in volumes spanning more than twelve orders of magnitudes, from bulk reactions to microfluidics and artificial cell systems2, 10–13.

The bottom-up construction of synthetic cells that recapitulates gene expression has become an effective means to characterize biological functions in isolation and to prototype cell-sized compartments as chemical bioreactors for applications in biotechnology14, 15. In particular, engineering artificial cells integrating active membrane functions is critical to develop mechanically robust compartments capable of sensing the physical and chemical environment. Such undertaking, however, remains challenging as only a few synthetic cell systems loaded with executable genetic information and harboring membrane sensors have been achieved16. In this work, we construct synthetic cells capable of responding to the osmotic pressure by expressing the E. coli mechanosensitive membrane protein MscL using a TXTL system encapsulated into synthetic liposomes. Using the calcium sensitive reporter G-GECO, we demonstrate that the osmotic pressure and calcium intake can be detected simultaneously, at different concentrations of the divalent ion. TXTL is carried out with a highly versatile all E. coli cell-free toolbox based on the endogenous transcription machinery (E. coli core RNA polymerase and sigma factor 70, σ70). We characterize the channel function by monitoring the fluorescence of G-GECO and the leak of polymers of various sizes. Our novel approach expands the functional capabilities of encapsulated cell-free TXTL reactions and demonstrates, for the first time, that synthetic cell systems with biosensing interfaces can be achieved by directly expressing membrane proteins inside liposomes.

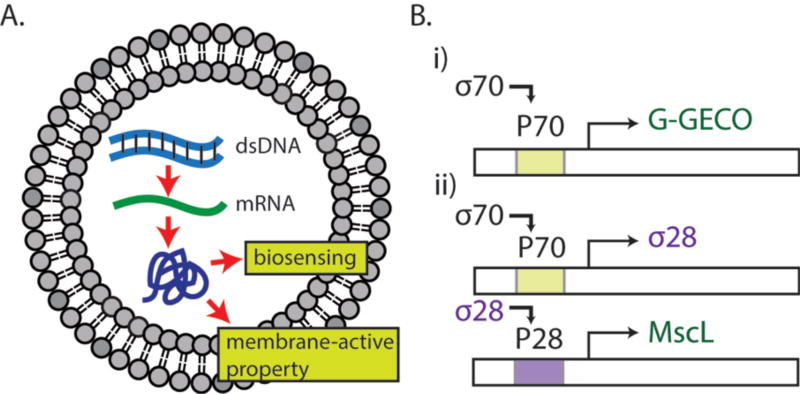

Our general methodology is to encapsulate TXTL reactions within phospholipid vesicles as a versatile platform that recapitulates in vitro transcription-translation for producing proteins that endow biosensing and molecular transport properties to the vesicles (Fig. 1A). DNA-based cell-free protein synthesis inside liposomes links the information contained in the DNA to the phenotype of synthetic cells in a reduced environment suitable for isolation and characterization of cellular functions. Like a complex chemical reaction that can be broken down to elementary processes, biochemical reactions based on genetic circuits can also be constructed to control rates of protein production. Such settings are conveniently adjusted in TXTL by either choosing the appropriate plasmids stoichiometry and circuit architectures, or by calibrating the strength of promoters and ribosome binding sites2. In this work, we used two different genetic circuit schemes to produce proteins of interests (Fig. 1B). In the first scheme, the endogenous E. coli core RNA polymerase σ70 drives the transcription of downstream coding sequence through the constitutive promoter P70a2. Our second scheme is a transcriptional activation cascade where P70a/σ70 drives the expression of sigma factor 28 (σ28) that is required for subsequent expression from a P28a promoter sequence specific to σ28. We first used the reporter protein deGFP to characterize the circuit functions and features2. deGFP is a slightly modified version of eGFP with identical fluorescence properties. Both schemes were then used to express G-GECO, a genetically encoded green fluorescence protein whose fluorescence depends on calcium concentration17, and the E. coli mechanosensitive channel of large conductance (MscL) for biosensing and incorporating a membrane-active property, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Schematics of protein synthesis in liposomes and gene circuits. (A) dsDNA is transcribed into mRNA, which is then translated to a biosensing fluorescent reporter protein (G-GECO) and a mechanosensitive membrane-active protein (MscL). (B) Gene circuits used in this work. (i) The E. coli housekeeping transcription factor sigma 70 activates the promoter P70a. (ii) The sigma 28 cascade requires the expression of sigma 28 protein, expressed through the P70a promoter. The sigma 28 transcription factor activates the corresponding promoter P28a.

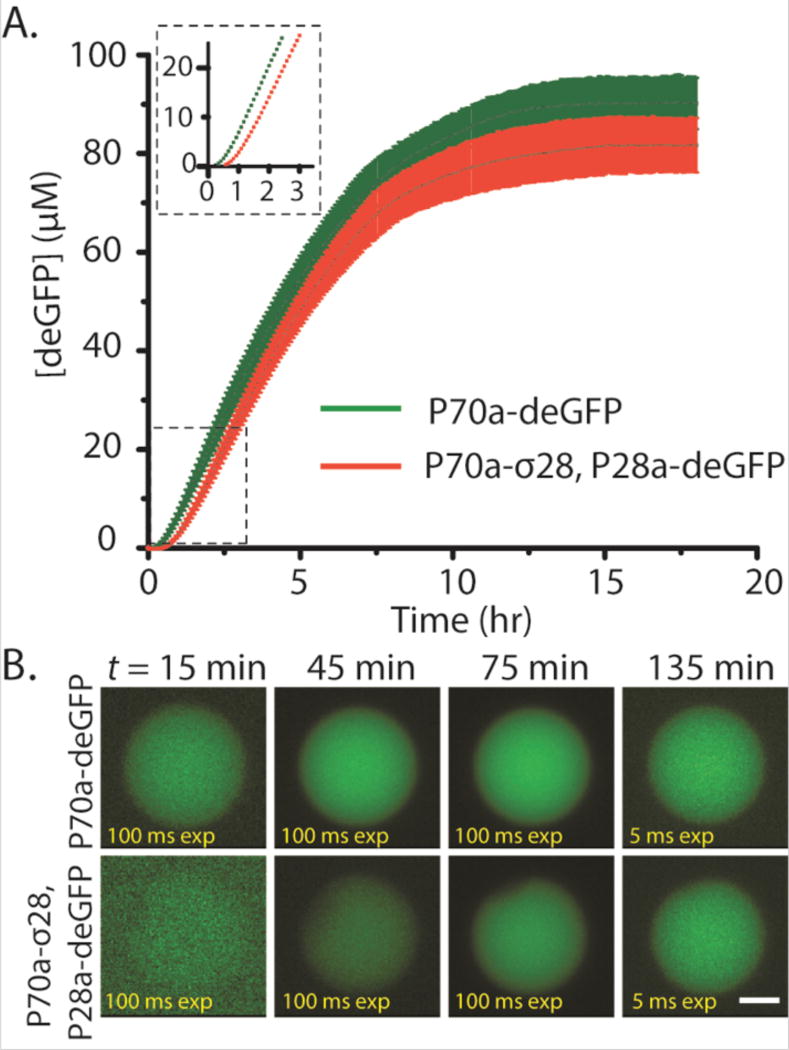

We first performed bulk reactions (10 µl reactions) and compared deGFP expression kinetics of the single-step circuit vs. the transcriptional activation cascade circuit. As expected, the requirement for σ28 to drive expression of deGFP in the transcriptional activation resulted in a delay in deGFP expression compared to the single-step circuit (Fig 2A). The delay observed for the cascade, on the order of 15 minutes, corresponded to the amount of time necessary for the synthesis of σ28. The bulk reaction persisted for many hours and deGFP production began to slow down after 8 hours and reached a plateau after 10 hours. The time course observed in these experiments is typical for TXTL reactions where protein synthesis ceases due to resource limitation (depletion of nucleotides and amino acids), change in the biochemical environment (pH) and accumulation of reaction byproducts. We next asked whether compartmentalization could preserve the delay in deGFP production that we observed in the bulk reactions. Using a single-step emulsion approach by vortexing aqueous TXTL reactions in 2% Span 80 dissolved in mineral oil, we produced emulsion droplets with a wide range of sizes encapsulating the TXTL reactions. As clearly evident, we observed deGFP expression as early as 45 minutes for the single-step circuit compared to relatively weak fluorescence after 1 hour for the transcriptional activation cascade (Fig. S1). Fluorescence intensity reached maximum after ~ 2 hours in both cases. The shorter protein production time in single emulsions is consistent with a faster rate of resource depletion in a compartmentalized system as compared to a bulk system10, as well as to the limited supply of oxygen necessary for cell-free TXTL. We next created synthetic cells by encapsulating TXTL reactions into phospholipid vesicles that have a physical boundary comparable to real living cells. We used a reverse emulsion technique for generating liposomes2 and we accounted for the delay in imaging start time due to preparation (estimated to be ~15 min). Because of the initial low protein production in vesicles, we acquired images at a high exposure time during the first hour (100 ms compared to 5 ms after 75 minutes of incubation) so that some fluorescence signals were observable at the earlier time points. Consistent with the experiments carried out under bulk conditions and in single emulsions, there was a clear delay in deGFP production in the transcriptional activation cascade (Fig. 2B). deGFP production leveled off after ~10 hours. The longer lasting expression compared to single emulsion is likely due to the availability of oxygen from the outer aqueous solution. Together, these experiments demonstrate that a cascaded circuit can delay reporter expression and that we can achieve robust protein expression by compartmentalizing CFE reactions.

Fig. 2.

deGFP synthesis in bulk reactions, single emulsions, and liposomes. (A) Kinetics of expression. Plasmid P70a-deGFP fixed at 5 nM, P70a-S28 fixed at 0.2 nM, and P28a-deGFP fixed at 5 nM. Inset: 0–3 hours magnified. (B) deGFP synthesis in liposomes using both the P70a plasmid and P28a cascade. Scale bar: 5 µm.

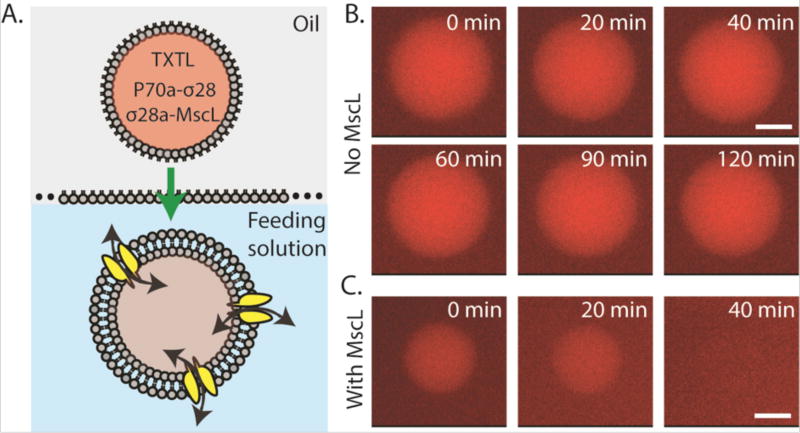

Phospholipid vesicles are particularly useful for encapsulating TXTL reaction in cell-sized compartments because lipidic bilayers are the natural substrates for membrane proteins such as channels and receptors. Expressing membrane proteins is a critical step towards constructing synthetic cells with functional interfaces to provide, for instance, transport or catalytic capabilities to a vesicle. In this regard, only a few of such artificial systems with membrane protein channels and sensors have been achieved so far11, 16. As a model system, we expressed MscL using the cascaded transcriptional activation circuit. MscL is a bacterial membrane protein that senses an increase in membrane tension and opens a pore of ~2.5 nm diameter to allow influx/efflux of molecules down the concentration gradient. It is thought to serve as the emergency release valve during osmotic downshock without which bacteria can lyse due to elevated osmotic pressure. We and others have shown that an increase in osmotic pressure or membrane tension can directly gate MscL18–20. Integrating active MscL into the membrane of synthetic cells by CFE is important for several reasons. First, it provides increased mechanical robustness to the vesicles against bursting by equilibrating osmotic pressure. It is a necessary step towards constructing synthetic cells robust enough to be used outside laboratory conditions. Second, the channel diameter is ideal to pass small nutrients molecules and feed the synthetic cells, while keeping the TXTL machineries inside. Third, it demonstrates that TXTL supports the expression of mechanosensitive membrane proteins that could be used as a means to test MscL mutants in the future. When expressing MscL using the transcriptional activation cascade, the delay in MscL expression (about 15 minutes) is advantageous because it corresponds to the amount of time needed to prepare the liposomes. We first expressed MscL-eGFP to visualize MscL localization. We observed the accumulation of MscL-eGFP at the membrane over time as expected (Fig. S2). In order to test MscL function, we developed a simple dye-leakage assay where TRITC-labeled dextrans of different molecular weight (3, 10, and 70 kDa) and TXTL reaction producing wild type MscL were co-encapsulated using the emulsion method to make liposomes (Fig. 3A). We expressed the native MscL without a fluorescent protein tag as MscL fusion proteins have a higher activation tension threshold18. In our experiments, we relied on the osmotic pressure from a hypo-osmotic feeding solution (~630 mOsm) relative to the encapsulated TXTL reaction (~700 mOsm). In the absence of MscL expression, 5 µM of 3,000 Da TRITC-dextran remained encapsulated in the vesicle after 2 hours (Fig. 3B). In contrast, MscL expression led to dye-leakage after 20–30 minutes. When a larger 10,000 Da TRITC-dextran was used, we observed complete dye-leakage after 60 minutes in MscL-expressing vesicles (Fig. S3A and S3B). Larger dextran molecules at 70,000 Da were completely retained after 120 minutes with or without MscL expression (Fig. S3C), with no leakage observed after 12 hours of incubation (data not shown). We also tested the leakage of two proteins, deGFP (27 kDa) and BSA-TRITC (60 kDa). Both were also completely retained inside the liposomes in MscL-expressing vesicles after 2 hours of incubation (Fig. S3D). No leakage was observed after overnight incubation (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Leakage of a 3 kDa TRITC-dextran in liposomes in the absence or presence of MscL. (A) Schematic of the encapsulation of a cell-free reaction containing 3 kDa TRITC-Dextran (5 µM), P70a-S28 (0.2 nM), and P28a-MscL (5 nM) into liposomes via the water-in-oil emulsion transfer method. (B) Fluorescence images of liposomes containing 3 kDa TRITC-dextran over a 2-hour period with only P70a-S28 added to the cell-free reaction. (C) Fluorescence images of liposomes containing 3 kDa TRITC-dextran over a 40-minute period with P70a-S28 and P28a-MscL added to the cell-free reaction. Scale bar: 5 µm.

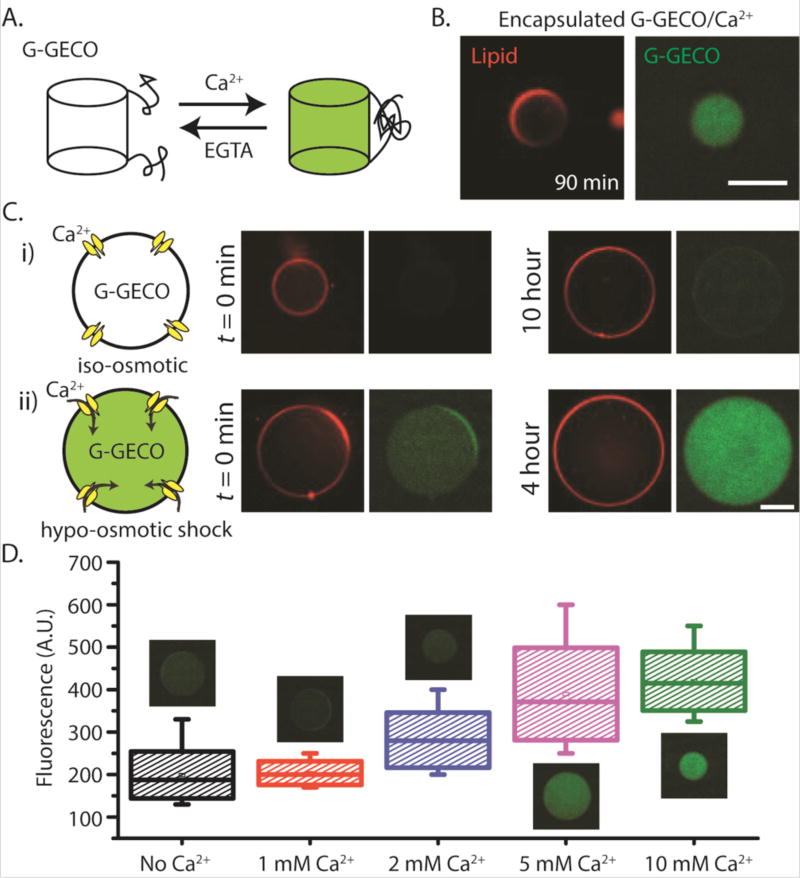

Our next challenge was to use a genetically-encoded reporter and demonstrate that we can couple a mechanical input to biosensing. We cloned the genetically-encoded calcium ion (Ca2+) biosensor G-GECO that is composed of a circularly permuted GFP fused to the calmodulin (CaM)-binding region of myosin light chain kinase M13 at its N-terminus and CaM at its C-terminus21. G-GECO is dim in the absence of Ca2+ and bright when bound to Ca2+ with a Ca2+-dependent fluorescence increase of ~23–26 fold (Fig. 4A)7. We cloned G-GECO under the P70a promoter and verified that it can sense Ca2+ in a plate reader assay (Fig. S4A). To eliminate traces of Ca2+ present in TXTL reactions estimated to be up to 1 mM Ca2+, we added 1 mM EGTA to the TXTL reactions so that G-GECO can report an increase in calcium level when externally added to the reactions. Both G-GECO and MscL-eGFP can be produced together in a single TXTL reaction, as shown by the increased fluorescence level by G-GECO after adding 1 mM Ca2+ at 120 minutes after TXTL started (Fig. S4B).

Fig. 4.

Mechanosensitive and biosensing synthetic cell system. (A) Schematic depicting the reversible transformation between the fluorescent and non-fluorescent states of G-GECO protein in presence of calcium and EGTA. (B) Fluorescence images of G-GECO expression with calcium addition inside vesicles (1 nM P70a-G-GECO, 1.5 mM calcium chloride was added to TXTL reaction after 1.5 hour incubation prior to encapsulation). (C) (i), (ii)-Three plasmid expression under different external conditions. Concentrations of P70a-S28, P28a-MscL and P70a-G-GECO in cell-free reaction were fixed at 0.2 nM, 1.4 nM and 0.6 nM respectively. The outer solutions for all conditions contained 10 mM calcium chloride. (D) Box plot showing the relative fluorescence intensities from vesicles in hypo-osmotic media with different external calcium concentrations. Each box corresponds to intensity values from ten vesicles. Plasmid concentrations of P70a-S28, P28a-MscL and P70a-G-GECO were 0.4 nM, 1.3 nM and 1 nM respectively. For both (C) and (D), the lipid vesicles were introduced into hypo-osmotic solution immediately after encapsulation following a 1.5 hour incubation period. EGTA was used at a concentration of 1 mM in all cell-free reactions. The osmolarity difference between iso-osmotic and hypo-osmotic solutions was measured at 100 mOsm. All experiments were repeated three times under identical conditions. Scale bars: 50 µm.

To create mechanosensitive-biosensing vesicles, we employed double emulsion templated vesicles generated by droplet microfluidics22, 23. We have previously used this approach and showed that small molecules from the feeding solution can enter encapsulated vesicles containing integrated synthesis, assembly, and translation (iSAT) reactions10. We have also shown that Ca2+ can enter a double emulsion droplet with an ultrathin oil layer as the middle phase when the droplet is under hypo-osmotic shock24. However, Ca2+ as a charged ion cannot across a lipid bilayer. When G-GECO was expressed in the presence of 1.5 mM Ca2+ inside a vesicle, fluorescence was readily detected after 90 minutes, demonstrating that G-GECO can be used to detect increased calcium concentration in an artificial cell (Fig. 4B). As expected, if Ca2+ is added to the outside (at 10 mM) of G-GECO expressing vesicle, no G-GECO fluorescence was observed because Ca2+ is impermeable to phospholipid membrane (Fig. S5A). However, addition of a calcium ionophore A23187 allowed rapid entry of Ca2+ and G-GECO fluorescence was readily observed in as little as 10-minute post A23187 addition (Fig. S5B).

To couple mechanical input to sensing the external environment, we co-expressed G-GECO (under P70a promoter) and MscL (under P28a promoter) in TXTL for 2 or 3 hours and then encapsulated the reaction into double emulsion templated vesicles. Under iso-osmotic condition, we did not observe G-GECO fluorescence for over 10 hours, our longest observation time point (Fig. 4Ci). In contrast, hypo-osmotic condition of ~100 mOsm osmotic difference between inside and outside the vesicle robustly led to an increase in G-GECO fluorescence as Ca2+ was able to enter the lipid bilayer membrane through MscL (Fig. 4Cii). To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of an AND-gate composed of a mechanical input (i.e. hypo-osmotic pressure) and an external chemical input (i.e. Ca2+) that lead to a specific fluorescence response. The synthetic cell system is also sensitive to the concentration of calcium added to the external solution (Fig. 4D and Fig. S6). The detection time for calcium intake was as short as 20 minutes.

In summary, we have generated a DNA-programmed cell-sized artificial cell that senses osmotic pressure and external calcium concentration. We demonstrated two different circuit architectures for TXTL that exhibit different reaction kinetics that are preserved across length scale from bulk reactions to micron-sized encapsulated droplets or vesicles. The ability to endow artificial cells with mechanosensitive functions to sense external small molecules using genetically-encoded biosensors allows for rapid sensing, rather than relying on fluorescence reporter synthesis using chemical inducers that most studies have used25, 26. Recapitulating TXTL for synthetic cell engineering can be used for reconstituting cellular processes and functions27. It can also serve as a powerful platform for chemical applications, such as biosensing and novel synthetic pathways for chemicals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Takanari Inoue (Johns Hopkins University) for providing the G-GECO plasmid. This work is supported by the NSF MCB-1612917 to A.P.L. and MCB-1613677 to V.N, the NIH Director’s New Innovator Award DP2 HL117748-01 to A.P.L., and the Human Frontier Science Program grant number RGP0037/2015 to V.N.. Y.-L.W. acknowledges support from the Global Networking Talent 3.0 Plan by Medical Device Innovation Center, NCKU. M.D. is supported by a NSF graduate fellowship.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Materials and methods and Supplementary Figures. See DOI: 10.0.39/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.Carlson ED, Gan R, Hodgman CE, Jewett MC. Biotechnol Adv. 2012;30:1185–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garamella J, Marshall R, Rustad M, Noireaux V. ACS Synth Biol. 2016;5:344–355. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwane Y, Hitomi A, Murakami H, Katoh T, Goto Y, Suga H. Nat Chem. 2016;8:317–325. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tayar AM, Karzbrun E, Noireaux V, Bar-Ziv RH. Nature Physics. 2015;11:1037–1041. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pardee K, Slomovic S, Nguyen PQ, Lee JW, Donghia N, Burrill D, Ferrante T, McSorley FR, Furuta Y, Vernet A, Lewandowski M, Boddy CN, Joshi NS, Collins JJ. Cell. 2016;167:248–259. e212. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng PP, Jia M, Patel KG, Brody JD, Swartz JR, Levy S, Levy R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:14526–14531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211018109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chemla Y, Ozer E, Schlesinger O, Noireaux V, Alfonta L. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;112:1663–1672. doi: 10.1002/bit.25587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong SH, Kwon YC, Jewett MC. Front Chem. 2014;2:34. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2014.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi MK, Hayes CA, Chappell J, Sun ZZ, Murray RM, Noireaux V, Lucks JB. Methods. 2015;86:60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caschera F, Lee JW, Ho KK, Liu AP, Jewett MC. ChemCommun (Camb) 2016;52:5467–5469. doi: 10.1039/c6cc00223d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noireaux V, Libchaber A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17669–17674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408236101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karzbrun E, Tayar AM, Noireaux V, Bar-Ziv RH. Science. 2014;345:829–832. doi: 10.1126/science.1255550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho KK, Lee JW, Durand G, Majumder S, Liu AP. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pohorille A, Deamer D. Trends Biotechnol. 2002;20:123–128. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(02)01909-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujii S, Matsuura T, Sunami T, Nishikawa T, Kazuta Y, Yomo T. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:1578–1591. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamada S, Tabuchi M, Toyota T, Sakurai T, Hosoi T, Nomoto T, Nakatani K, Fujinami M, Kanzaki R. Chem Commun (Camb) 2014;50:2958–2961. doi: 10.1039/c3cc48216b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao Y, Araki S, Wu J, Teramoto T, Chang YF, Nakano M, Abdelfattah AS, Fujiwara M, Ishihara T, Nagai T, Campbell RE. Science. 2011;333:1888–1891. doi: 10.1126/science.1208592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox CD, Bae C, Ziegler L, Hartley S, Nikolova-Krstevski V, Rohde PR, Ng CA, Sachs F, Gottlieb PA, Martinac B. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10366. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee LM, Liu AP. Lab Chip. 2015;15:264–273. doi: 10.1039/c4lc01218f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heureaux J, Chen D, Murray VL, Deng CX, Liu AP. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2014;7:307–319. doi: 10.1007/s12195-014-0337-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su S, Phua SC, DeRose R, Chiba S, Narita K, Kalugin PN, Katada T, Kontani K, Takeda S, Inoue T. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1105–1107. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho KK, Murray VL, Liu AP. Methods Cell Biol. 2015;128:303–318. doi: 10.1016/bs.mcb.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Utada AS, Lorenceau E, Link DR, Kaplan PD, Stone HA, Weitz DA. Science. 2005;308:537–541. doi: 10.1126/science.1109164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho KK, Lee LM, Liu AP. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32912. doi: 10.1038/srep32912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shin J, Noireaux V. ACS Synth Biol. 2012;1:29–41. doi: 10.1021/sb200016s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siuti P, Yazbek J, Lu TK. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:448–52. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu AP, Fletcher DA. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:644–650. doi: 10.1038/nrm2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.