Abstract

The TIPE (tumor necrosis factor-α-induced protein 8-like) family are newly described regulators of immunity and tumorigenesis consisting of four highly homologous mammalian proteins: TNFAIP8 (tumor necrosis factor-α-induced protein 8), TIPE1 (TNFAIP8-like 1, or TNFAIP8L1), TIPE2 (TNFAIP8L2) and TIPE3 (TNFAIP8L3). They are the only known transfer proteins of the lipid secondary messengers PIP2 (phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate) and PIP3 (phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate). Cell-surface receptors, such as G-protein-coupled receptors and receptor tyrosine kinases, regulate inflammation and cancer via several signaling pathways, including the nuclear factor (NF)-κB and phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K) pathways, the latter of which is upstream of both Akt and STAT3 activation. An expression analysis in humans demonstrated that the TIPE family is dysregulated in cancer and inflammation, and studies both in mice and in vitro have demonstrated that this family of proteins plays a critical role in tumorigenesis and inflammatory responses. In this review, we summarize the current literature for all four family members, with a special focus on the phenotypic manifestations present in the various knockout murine strains, as well as the related cell signaling that has been elucidated to date.

Keywords: inflammation, PI3K, TIPE, TNFAIP8, tumorigenicity

Introduction

The linkage between inflammation and cancer has long been appreciated,1 and recent data have elucidated some of the mechanisms underlying this linkage.2 Specifically, NF-κB and STAT3 signaling are central pathways that link these two biological processes.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), responsible for a large share of cell-surface signaling, are central to this relationship and exhibit a diverse range of functions: they couple with heterotrimeric G-proteins, and the activation of the receptors leads to Gα- and Gβγ-mediated signaling, which exerts several receptor- and cell-specific signaling effects.

Gβγ-mediated signaling has been noted to be important for inflammation and cancer. For example, GPCR signaling extensively regulates NF-κB signaling via this complex8 and is associated with tumor metastasis through the regulation of cell migration. Dissociated (active) Gβγ activates the small G-protein Ras, predominately at the leading edge of migrating cells. Ras activates phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K), which converts phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2 or PIP2) to PI(3,4,5)P3 (PIP3).9 In addition to GPCRs, tyrosine kinases, such as the Janus kinase (JAK) family and growth factor receptors, activate PI3K signaling.10

Once PIP2 has been converted to PIP3, it can recruit proteins with Pleckstrin homology domains to the plasma membrane at the leading edge, including AKT11 (which has a central role in oncogenesis, often via mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin)12) and polybasic domain-containing proteins, such as the RAC and Cdc42 members of the Rho family of small GTPases.13 During cell migration, active RAC-GTP preferentially localizes to the leading edge (lamellipodia) at the front of the cell, where it drives the polymerization of actin. PI3K activation can also activate the STAT3 pathway, which is strongly linked to both inflammation and cancer14, 15 and engages in significant crosstalk with NF-κB signaling.16

The TIPE (tumor necrosis factor-α-induced protein 8-like, or TNFAIP8L) family are newly described regulators of immunity and tumorigenesis17, 18 that are the only known transfer proteins of the lipid second messengers PIP2 and PIP319 which are central to Gβγ signaling. Four highly homologous mammalian family members have been identified: TNFAIP8 (tumor necrosis factor-α-induced protein 8); TIPE1 (TNFAIP8L1); TIPE2 (TNFAIP8L2); and TIPE3 (TNFAIP8L3). TNFAIP8 expression is induced by TNF,20 promotes tumor metastasis and is a risk factor for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in humans and bacterial infection in mice.21, 22 Similarly, TIPE2 regulates both carcinogenesis and inflammation, and its germline deletion leads to leukocytosis and systemic inflammatory disorders in aged, 129-strain mice.18, 23 Moreover, TIPE1 has been reported to regulate cell death,24 whereas the oncogenic role of TIPE3 has just been characterized by us.19

To date, the TIPE family has exhibited significant overlap in signaling with the molecules involved in chemotaxis, and perturbations in TIPE signaling alter inflammation, tumorigenicity and wound healing. This review focuses on the phenotypic manifestations of perturbations in TIPE signaling, the known signaling cascades that the TIPE family is involved in, and the known structural biology of TIPE proteins.

TNFAIP8 (TIPE0), the original TIPE family member, is a negative regulator of apoptosis and is oncogenic

TNFAIP8 was the first TIPE family protein to be discovered. It was originally known as SCC-C2, as it was found in a cell line derived from metastatic head and neck squamous cell cancer and was determined to be a negative regulator of apoptosis in overexpression assays.17, 20, 25 Its expression levels correlate with the tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma,26 and a similar pattern has been observed in pancreatic cancer,27 gastric adenocarcinoma28 and endometrial cancer.29 It is also a risk factor for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and high levels of TNFAIP8 expression are associated with more aggressive forms of epithelial ovarian cancer with poor survival rates22, 30 as well as with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).31 Furthermore, the overexpression of TNFAIP8 protein in the MDA-MB 435 human breast cancer cell line resulted in increased cell proliferation and cell migration,17 which was demonstrated to enhance tumorgenicity32 when injected in athymic mice. In contrast, antisense inhibition in athymic mice resulted in a decreased incidence of pulmonary metastasis.32 TNFAIP8 expression is also increased in diabetic kidneys, and it is upregulated in mesangial cells in response to high glucose levels, with concordant mesangial cell proliferation enhancement.33 Moreover, TNFAIP8 protein is known to be induced by NF-κB activation,34 a central pro-proliferative, anti-apoptotic transcription factor.35

Mechanistic studies have shown that decreased TNFAIP8 expression led to concomitant decreases in the levels of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) and matrix metalloprotease (MMP) 1 and 9.32 In addition, TNFAIP8 has been shown to be directly coupled to Gαi g-proteins; this interaction does not appear to be involved in Gαi3-mediated cAMP inhibition but is involved in Gi-mediated inhibition of cell death, presumably via the Gβγ subunit.36 TNFAIP8 protein has also been found to associate with activated RAC1-GTP at the cell membrane,37 and the knockout of this protein resulted in resistance to lethal Listeria monocytogenes infection via decreased RAC1-mediated cell invasion and increased apoptosis.37 Knocking out the TNFAIP8 gene also exacerbated disease in a dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) model of murine colitis, and the data suggested that this effect was due to decreased epithelial cell survival in the face of the chemical insult.38 Knocking down TNFAIP8 also excacerbates oxidative stress-mediated autophagic cell death in a manner involving decreased mTOR activation.39 In contrast to the aforementioned studies, the downregulation of TNFAIP8 has also been shown to prevent glucocorticoid-mediated apoptosis in thymocytes.40

TIPE1 is an enhancer of apoptosis

TIPE1, also known as Oxi-β, was first characterized in 2011 after the development of a specific antibody to this protein. In mice, TIPE1 was found to be expressed in a wide variety of tissues, including neurons, hepatocytes, muscle tissue, intestinal epithelial cells and germ cells, but surprisingly, it was absent from mature B and T cells.41 TIPE1 is known to be downregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tissues in a manner that correlates with TNM staging and patient death.42

In HCC cell cultures, TIPE1 was found to interact with Rac1, inhibiting activation of downstream p65 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling, which increased caspase-mediated apoptosis.42 In a dopaminergic neuronal cell line and in rats, oxidative stress increased TIPE1 transcription and translation, with downstream increases in autophagy and cell death, whereas knocking down the TIPE1 gene decreased this phenomenon. This effect was mediated, at least in part, by TIPE1-dependent mTOR inhibition.43 Further studies demonstrated that TIPE1 was able to compete with TSC2 (tuberous sclerosis complex 2) for binding to FBXW5, and the overexpression of TIPE1 led to the accumulation of TSC2, which is a negative regulator of mTOR.43 Moreover, TIPE1 was found to only weakly interact with Gαi as compared with TNFAIP8.36

TIPE2 is a negative regulator of immunity and inflammation

We first reported TIPE2 in 2008, which was found to be widely expressed in lymphoid tissues; its knockout in mice resulted in the development of spontaneous multi-organ inflammation, splenomegaly and premature death, and these mice were hypersensitive to Toll-like receptor (TLR) stimulation.18 Follow-up expression studies in mice have found that TIPE2 is preferentially expressed in hematopoietic cells, particularly T cells (including regulatory T cells),44 whereas it is almost absent from B cells and the B cell zones of lymphoid tissues.45 In human studies, TIPE2 was found to be much more widely expressed; notably, it was found to be expressed only in differentiated, not progenitor, squamous epithelial cells.46

TIPE2 has been investigated in the setting of several human diseases. In patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, TIPE2 mRNA expression was found to be decreased in peripheral blood monocytes (PMBCs) compared with healthy controls, and its expression levels inversely correlated with disease activity.47 Similarly, patients with childhood asthma exhibited decreased levels of TIPE2 expression compared with healthy controls, and the levels of TIPE2 inversely correlated with mediators of asthma, namely eosinophils, IgE, and IL-4. This pattern was also present in the PMBCs of patients with myasthenia gravis, with increased levels of IL-6, IL-17 and IL-21 correlating with decreased TIPE2 expression.48

Patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection were also shown to have decreased levels of TIPE2, and its expression was negatively associated with viral load and serum markers of liver inflammation. Moreover, the PMBCs of these patients were preferentially decreased in cytotoxic T cells with an accompanying increase in disease activity.49 A similar pattern was observed in the PMBCs of patients with hepatitis C virus infection.50 In contrast, patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure (ACHBLF) were found to have increased levels of TIPE2 expression, and ex vivo studies suggested that the cellular immune response was decreased in patients with ACHBLF, as evidenced by diminished cytokine production upon lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation and the associated upregulation of TIPE2 expression. Increased levels of TIPE2 expression have also been found to correlate with mortality in patients with ACHBLF.51 In contrast, the TIPE2 protein levels are decreased in the PMBCs of patients with primary biliary sclerosis, and inflammatory cytokine production was found to be inversely related to TIPE2 expression; furthermore, TIPE2 expression is upregulated by ursodeoxycholic acid.52

In neoplastic studies, TIPE2 expression has been found to be decreased or completely lost in human hepatic cancer,23 and reduced TIPE2 expression is associated with metastasis. It is also downregulated in gastric cancer tissues,53 NSCLC tumors54 and small cell lung cancer tumors,55 and the levels of TIPE2 inversely correlate with NSCLC TNM staging.54 Moreover, reduced TIPE2 expression is associated with metastasis of hepatic cancer.56 In contrast, TIPE2 expression was increased in the tumor tissues of patients with renal cell carcinoma and positively correlated with TNM staging.57 Similarly, TIPE2 expression is increased in colon cancer tissues and is associated with lymph node metastases and the Duke stage of the cancer.58

In mouse models, TIPE2 ablation exacerbated cerebral ischemia,59 whereas ablation decreased colonic inflammation and cell death in DSS colitis, an effect attributed to enhanced killing of the commensal microbiota that invade the gut wall during DSS colitis.60 In an injury-induced restenosis models in mice, the loss of TIPE2 increased vascular smooth muscle proliferation with increased restenosis.61 Furthermore, TIPE2 overexpression reduced disease severity and polarized macrophages to an M2 phenotype in a murine lupus model.62

Mechanistically, TIPE2 has been found to bind to and activate caspase-8, promote Fas-induced apoptosis and inhibit NF-κB activating protein-1.18, 58 It is also a negative regulator of NOD2 inflammatory signaling.63 Similar to TIPE1, it only weakly interacts with Gαi,36 Knockdown of TIPE2 in regulatory T cells (Tregs) decreases the expression levels of the cell-surface molecules CTLA-4 and Foxp3 and anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β. These modified cells result in the upregulation of IL-2 expression and increased nuclear factor of activated T cells activation as well as T-cell proliferation and differentiation.44 Similarly, dsRNA signaling via polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid [Poly (I:C)] is hyperactive in TIPE2 knockout myeloid cells, and Poly (I:C) signaling leads to the downstream cytokine-mediated downregulation in TIPE2 expression.64 TIPE2 has also been shown to induce Foxp3 in Tregs65 and through dendritic cells can inhibit T-cell proliferation and differentiation.66 Furthermore, TIPE2 has recently been implicated as the molecular bridge for the microRNA (miRNA)-21-mediated suppression of T-cell apoptosis; miRNA-21 was found to be a direct target of NF- κB and to decrease TIPE2 expression, which results in apoptosis resistance.67

TIPE2 has also been found to bind to and inhibit Rac, inhibiting downstream activation of AKT and Ral; deficiency in TIPE2 protein increased the activation of Ral and AKT, with associated resistance to cell death and increased cell migration as well as the dysregulation of exocyst complex formation. In vascular smooth muscle cells, TIPE2 was found to inhibit Rac1-mediated STAT3 activation, nuclear translocation and Erk1/2 activation.23 In HCC, TIPE2 reduces Rac-mediated F-actin polymerization and the expression of MMP-9 and urokinase plasminogen activator, and a loss of TIPE2 in this setting is associated with metastasis.56 It also inhibits the TNF-mediated activation of Erk1/2 and NF-κB in an HCC cell line.68 In contrast, TIPE2 overexpression induced cell death and inhibited Ras-mediated tumorigenesis in mice.23 In gastric cell lines, increased TIPE2 expression decreased cell proliferation by upregulating N-ras and p27 expression,53 the latter of which is mediated by interferon regulatory factor 4 via NF-κB;69 TIPE2 has also been found to regulate AKT and ERK1/2 signaling in these cells70 as well as GSK3β and downstream β-catenin translocation.71 Finally, TIPE appears to regulate angiogenesis in retinal pigment epithelium by inhibiting VEGF.72

TIPE2 is also a negative regulator of phagocytosis and oxidative burst induced by TLRs, and knockout mice were found to be resistant to bacterial infections.73 Similarly, the loss of TIPE2 led to increased induced nitric oxide production by macrophages upon LPS stimulation.74 TIPE2 may also be a negative inhibitor of atherosclerosis formation because TIPE2 inhibited smooth muscle proliferation and differentiation, whereas TIPE2 deficiency accelerated neointima formation.75 In addition, TIPE2 regulates macrophage responses to oxidized low-density lipoproteins (ox-LDL); TIPE2-deficient macrophages produced more oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines, with associated increases in JNK, NF- κB, and p38 signaling.76 In conjunction with this finding, TIPE2 deficiency in the bone marrow increased atherosclerosis formation in Ldlr−/− mice fed a high-fat diet, and ox-LDL was found to downregulate TIPE2 mRNA expression.76 Interestingly, atorvastatin seems to potentiate the LPS-mediated expression of TIPE2, with downstream decreases in inflammatory mediators, including NO synthase and NF- κB.77

TIPE3 is an oncogenic transfer protein of lipid second messengers

TIPE3 is the most recently investigated TIPE family member, and only a few articles have been published regarding this protein. Human cancers (cervical, colon, lung and esophageal) exhibit marked increases in TIPE3 expression,19, 78 and TIPE3 protein is preferentially expressed in secretory epithelial tissues, with nearly identical murine and human expression profiles.78 It potentiates PI3K signaling and downstream Akt (but not Erk) signaling, and knocking down TIPE3 diminishes tumorigenesis in animal models, whereas enforced expression increases tumorigenesis.19 Structure/function studies (discussed below) suggest that it shuttles PIP2 and PIP3 to the plasma membrane to potentiate PI3K-related signaling.19

Structure/function studies of the TIPE family members provide key insights into their functional differences

The crystal structures of TIPE2 and TIPE3 both demonstrate a hydrophobic pocket that, based on structural analysis, may bind phospholipids.19, 79 All TIPE members share a common TIPE2-homology (TH) domain and are able to interact with an array of phospholipids, namely PtdIns(4,5)P2, PtdIns(3,5)P2, PtdIns(3,4)P2, PtdIns4P, PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PA.19 Mutation studies in the binding pockets of TIPE3 demonstrated that the introduction of electrostatic charge resulted in a loss of phospholipid binding, supporting the role of the pockets as phospholipid binding sites.19 The disruption of this binding site also inhibited TIPE3 function. In addition, TIPE3 contains a unique N-terminal domain that is required for its activating functions; the deletion of this domain preserves phosphoinositide binding but results in a dominant negative, inhibitory phenotype akin to TIPE2 function.19

Conclusions

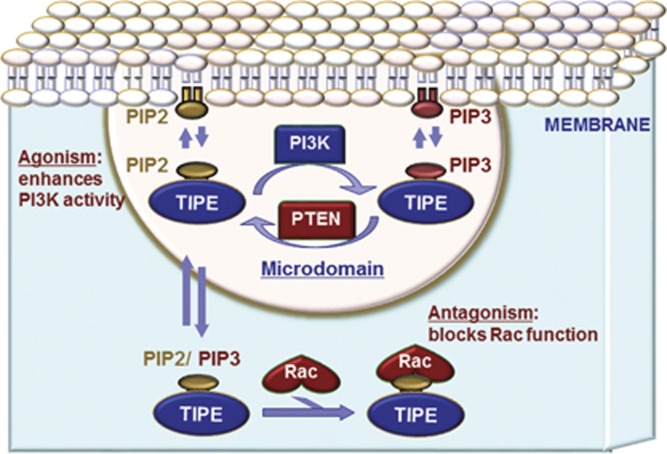

The TIPE family of proteins represents a novel protein group discovered just over a decade ago. Tissue expression studies show some variability among the proteins, with TNFAIP8 and TIPE1 being the most widely expressed family members and TIPE2 and TIPE3 being found preferentially in hematopoietic and secretory epithelial cells, respectively.19, 78 On the basis of structure/function studies of TIPE2 and TIPE3 and the homology of their shared TH domain, the TIPE family of proteins appears to be involved in phosphoinositide signaling to regulate PI3K and shuttle phospholipids to and from the plasma membrane (Figure 1).19 By regulating PI3K and downstream mediators, including AKT, Rac1, GSK3β, Erk1/2, NF-κB23, 37, 42 and other pathways discussed in this review (summarized in Table 1), the TIPE family modulates critical cellular functions, including regulating immune function, cell migration and the proliferation/apoptosis axis. TIPE1 and TIPE2 appear to be largely inhibitory, that is, they are pro-apoptotic and anti-proliferative. Unlike TIPE1,41 TIPE2, which is expressed in mature T cells,45, 46 also has an important role in immune regulation. In contrast, TNFAIP8 and TIPE3 appear to be largely anti-apoptotic, pro-proliferative and pro-migratory.19, 36 Accordingly, increases in the expression of the anti-apoptotic and pro-migratory TIPE members are associated with a variety of cancers, whereas the expression of pro-apoptotic and anti-migratory family members is decreased in this setting.

Figure 1.

The TIPE family of proteins regulates a wide array of cellular functions. In this figure and caption, 'TIPE' indicates any TIPE family member. Members of the TIPE family of proteins exert a variety of regulatory functions by acting as phospholipid transfer proteins. Specifically, TIPE3 appears to potentiate PI3K signaling, although all family members potentiate signaling downstream of PI3K to some extent. The TIPE family also appears to act as a negative regulator of signaling by directly binding to specific targets, such as Rac1. PI3K, phosphoinositide-3 kinase; TIPE, tumor necrosis factor-α-induced protein 8-like.

Table 1. Human cancer and signaling pathways with known associations with the various TIPE proteins.

| TIPE protein | Associated human cancers | Associated signaling pathways |

|---|---|---|

| TNFAIP8 (TIPE0) | Endometrial, gastric, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, NSCLC, ovarian, pancreatic, squamous cell | Gαi/Gβγ Rac1 mTOR MMP 1 and 9 VEGFR-2 |

| TIPE1 | HCC | Rac1/mTOR |

| TIPE2 | Colon, gastric, HCC, NSCLC, renal cell, SCLC | Caspase-8, Erk1/2, JNK, MMP-9, NF-AT, NF-κB, NF-κB activating protein-1, NOD2, p38, Rac1, STAT3 |

| TIPE3 | Cervical, colon, esophageal, lung | PI3K, Akt |

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; NA-FT, nuclear factor of activated T cells; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; SCLC, small cell lung cancer.

However, the body of literature on these proteins is relatively sparse, and their functional roles largely remain to be determined. TIPE2 has been the subject of the most intensive studies to date, perhaps partly due to the initial observation of its preferential lymphoid expression in mice.45 This observation led to a series of studies that have somewhat elucidated its role in immune system regulation. Despite these studies, the total body of work on all these proteins remains small; based on a PubMed search through 15 June 2016, the number of publications addressing the function of this family of proteins stands as follows: 25, four, 50 and two publications discuss TNFAIP8, TIPE1, TIPE2 and TIPE3, respectively. Consequently, much more is unknown than is known about these proteins. They all seem to have an important role in carcinogenesis and metastasis (Table 1) via either their up- or downregulation, but their exact molecular functions and the existence of any interactions or crosstalk between family members remain unknown.

Given the critical cellular roles members of the TIPE family are involved in, the aforementioned molecular functions and interactions are expected to be elucidated as more investigators enter the field. Given the current state of knowledge, specifically regarding the novel function of these proteins as secondary messenger phospholipid transporters, a better understanding of the function of the TIPE family of proteins could provide key insights into chemotaxis, proliferation and metastasis, with implications for the treatment of a wide array of human diseases, including malignancies and auto-immune diseases. The current era of research is an exciting time for TIPE researchers because this protein family remains on the frontier of molecular and cellular biology.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Cancer and inflammation: implications for pharmacology and therapeutics. Clin Pharmacol Therapeut 2010; 87: 401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur JC, Perez-Chanona E, Muhlbauer M, Tomkovich S, Uronis JM, Fan TJ et al. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science 2012; 338: 120–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Neriah Y, Karin M. Inflammation meets cancer, with NF-[kappa]B as the matchmaker. Nat Immunol 2011; 12: 715–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiDonato JA, Mercurio F, Karin M. NF-κB and the link between inflammation and cancer. Immunol Rev 2012; 246: 379–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt PK, Hart JR. PI3K and STAT3: a new alliance. Cancer Discov 2011; 1: 481–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivennikov S, Karin E, Terzic J, Mucida D, Yu G-Y, Vallabhapurapu S et al. IL-6 and Stat3 are required for survival of intestinal epithelial cells and development of colitis-associated cancer. Cancer Cell 2009; 15: 103–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nat Rev Cancer 2009; 9: 798–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye RD. Regulation of nuclear factor {kappa}B activation by G-protein-coupled receptors. J Leukoc Biol 2001; 70: 839–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki AT, Chun C, Takeda K, Firtel RA. Localized Ras signaling at the leading edge regulates PI3K, cell polarity, and directional cell movement. J Cell Biol 2004; 167: 505–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster FM, Traer CJ, Abraham SM, Fry MJ. The phosphoinositide (PI) 3-kinase family. J Cell Sci 2003; 116: 3037–3040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servant G, Weiner OD, Herzmark P, Balla T, Sedat JW, Bourne HR. Polarization of chemoattractant receptor signaling during neutrophil chemotaxis. Science 2000; 287: 1037–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini M, De Santis MC, Braccini L, Gulluni F, Hirsch E. PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and cancer: an updated review. Ann Med 2014; 46: 372–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin T, Xu X, Hereld D. Chemotaxis, chemokine receptors and human disease. Cytokine 2008; 44: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart JR, Liao L, Yates JR, Vogt PK. Essential role of Stat3 in PI3K-induced oncogenic transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108: 13247–13252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Lee H, Herrmann A, Buettner R, Jove R. Revisiting STAT3 signalling in cancer: new and unexpected biological functions. Nat Rev Cancer 2014; 14: 736–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Mao R, Yang J. NF-kappaB and STAT3 signaling pathways collaboratively link inflammation to cancer. Protein Cell 2013; 4: 176–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D, Gokhale P, Broustas C, Chakravarty D, Ahmad I, Kasid U. Expression of SCC-S2, an antiapoptotic molecule, correlates with enhanced proliferation and tumorigenicity of MDA-MB 435 cells. Oncogene 2004; 23: 612–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Gong S, Carmody RJ, Hilliard A, Li L, Sun J et al. TIPE2, a negative regulator of innate and adaptive immunity that maintains immune homeostasis. Cell 2008; 133: 415–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayngerts SA, Wu J, Oxley CL, Liu X, Vourekas A, Cathopoulis T et al. TIPE3 is the transfer protein of lipid second messengers that promote cancer. Cancer Cell 2014; 26: 465–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D, Whiteside TL, Kasid U. Identification of a novel tumor necrosis factor-alpha-inducible gene, SCC-S2, containing the consensus sequence of a death effector domain of fas-associated death domain-like interleukin- 1beta-converting enzyme-inhibitory protein. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 2973–2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn SH, Deshmukh H, Johnson N, Cowell LG, Rude TH, Scott WK et al. Two genes on A/J chromosome 18 are associated with susceptibility to Staphylococcus aureus infection by combined microarray and QTL analyses. PLoS Pathog 2010; 6: e1001088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Wang MY, He J, Wang JC, Yang YJ, Jin L et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induced protein 8 polymorphism and risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in a Chinese population: a case-control study. PLoS One 2012; 7: e37846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gus-Brautbar Y, Johnson D, Zhang L, Sun H, Wang P, Zhang S et al. The anti-inflammatory TIPE2 is an inhibitor of the oncogenic Ras. Mol Cell 2012; 45: 610–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitomi J, Christofferson DE, Ng A, Yao J, Degterev A, Xavier RJ et al. Identification of a molecular signaling network that regulates a cellular necrotic cell death pathway. Cell 2008; 135: 1311–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Wang FH, Whiteside TL, Kasid U. Identification of seven differentially displayed transcripts in human primary and matched metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines: implications in metastasis and/or radiation response. Oral Oncol 1997; 33: 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadisaputri YE, Miyazaki T, Suzuki S, Yokobori T, Kobayashi T, Tanaka N et al. TNFAIP8 overexpression: clinical relevance to esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2012; 19: S589–S596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Qin CK, Wang ZY, Liu SX, Cui XP, Zhang DY. Expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced protein 8 in pancreas tissues and its correlation with epithelial growth factor receptor levels. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2012; 13: 847–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Zhao Q, Wang X, Liu T, Yao G, Lou C et al. TNFAIP8 overexpression is associated with lymph node metastasis and poor prognosis in intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma. Histopathology 2014; 65: 517–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Gao H, Yang M, Zhao T, Liu Y, Lou G. Correlation of TNFAIP8 overexpression with the proliferation, metastasis, and disease-free survival in endometrial cancer. Tumour Biol 2014; 35: 5805–5814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Gao H, Chen X, Lou G, Gu L, Yang M et al. TNFAIP8 as a predictor of metastasis and a novel prognostic biomarker in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer 2013; 109: 1685–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Song Y, Men X. Variance of TNFAIP8 expression between tumor tissues and tumor-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in non-small cell lung cancer. Tumour Biol 2014; 35: 2319–2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Chakravarty D, Sakabe I, Mewani RR, Boudreau HE, Kumar D et al. Role of SCC-S2 in experimental metastasis and modulation of VEGFR-2, MMP-1, and MMP-9 expression. Mol Ther 2006; 13: 947–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Zhang Y, Wei X, Zhen J, Wang Z, Li M et al. Expression and regulation of a novel identified TNFAIP8 family is associated with diabetic nephropathy. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010; 1802: 1078–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You Z, Ouyang H, Lopatin D, Polver PJ, Wang CY. Nuclear factor-kappa B-inducible death effector domain-containing protein suppresses tumor necrosis factor-mediated apoptosis by inhibiting caspase-8 activity. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 26398–26404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karrasch T, Jobin C. NF-kappaB and the intestine: friend or foe? Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008; 14: 114–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laliberte B, Wilson AM, Nafisi H, Mao H, Zhou YY, Daigle M et al. TNFAIP8: a new effector for Galpha(i) coupling to reduce cell death and induce cell transformation. J Cell Physiol 2010; 225: 865–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porturas TP, Sun H, Buchlis G, Lou Y, Liang X, Cathopoulis T et al. Crucial roles of TNFAIP8 protein in regulating apoptosis and Listeria infection. J Immunol 2015; 194: 5743–5750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Lou Y, Porturas T, Morrissey S, Luo G, Qi J et al. Exacerbated experimental colitis in TNFAIP8-deficient mice. J Immunol 2015; 194: 5736–5742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KC, Kim SH, Ha JY, Kim ST, Son JH. A novel mTOR activating protein protects dopamine neurons against oxidative stress by repressing autophagy related cell death. J Neurochem 2010; 112: 366–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward MJ, de Boer J, Heidorn S, Hubank M, Kioussis D, Williams O et al. Tnfaip8 is an essential gene for the regulation of glucocorticoid-mediated apoptosis of thymocytes. Cell Death Differ 2010; 17: 316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Zhang G, Hao C, Wang Y, Lou Y, Zhang W et al. The expression of TIPE1 in murine tissues and human cell lines. Mol Immunol 2011; 48: 1548–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Liang X, Gao L, Ma H, Liu X, Pan Y et al. TIPE1 induces apoptosis by negatively regulating Rac1 activation in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncogene 2015; 34: 2566–2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha JY, Kim JS, Kang YH, Bok E, Kim YS, Son JH. Tnfaip8 l1/Oxi-beta binds to FBXW5, increasing autophagy through activation of TSC2 in a Parkinson's disease model. J Neurochem 2014; 129: 527–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan YY, Yao YM, Zhang L, Dong N, Zhang QH, Yu Y et al. Expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha induced protein 8 like-2 contributes to the immunosuppressive property of CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells in mice. Mol Immunol 2011; 49: 219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Hao C, Lou Y, Xi W, Wang X, Wang Y et al. Tissue-specific expression of TIPE2 provides insights into its function. Mol Immunol 2010; 47: 2435–2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Shi Y, Wang Y, Zhu F, Wang Q, Ma C et al. The unique expression profile of human TIPE2 suggests new functions beyond its role in immune regulation. Mol Immunol 2011; 48: 1209–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Song L, Fan Y, Li X, Li Y, Chen J et al. Down-regulation of TIPE2 mRNA expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Immunol 2009; 133: 422–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Liu X, Wei Z, Wang X, Wang Z, Zhong W et al. The expression and significance of TIPE2 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from asthmatic children. Scand J Immunol 2013; 78: 523–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi W, Hu Y, Liu Y, Zhang J, Wang L, Lou Y et al. Roles of TIPE2 in hepatitis B virus-induced hepatic inflammation in humans and mice. Mol Immunol 2011; 48: 1203–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L, Liu K, Zhang YZ, Jin M, Wu BR, Wang WZ et al. Downregulation of TIPE2 mRNA expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatol Int 2013; 7: 844–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LY, Fan YC, Zhao J, Gao S, Sun FK, Han J et al. Elevated expression of tumour necrosis factor-alpha-induced protein 8 (TNFAIP8)-like 2 mRNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells is associated with disease progression of acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure. J Viral Hepatitis 2014; 21: 64–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin B, Wei T, Wang L, Ma N, Tang Q, Liang Y et al. Decreased expression of TIPE2 contributes to the hyperreactivity of monocyte to Toll-like receptor ligands in primary biliary cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 31: 1177–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Zhao M, Dong T, Zhou C, Peng Y, Zhou X et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced protein-8 like-2 (TIPE2) upregulates p27 to decrease gastic cancer cell proliferation. J Cell Biochem 2015; 116: 1121–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Li X, Liu G, Sun R, Wang L, Wang J et al. Downregulated TIPE2 is associated with poor prognosis and promotes cell proliferation in non-small cell lung cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015; 457: 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu QQ, Zhang FF, Wang F, Qiu JH, Luo CH, Zhu GY et al. TIPE2 inhibits lung cancer growth attributing to promotion of apoptosis by regulating some apoptotic molecules expression. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0126176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Zhang L, Shi Y, Sun Y, Dai S, Guo C et al. Human tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha-induced protein 8-like 2 suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis through inhibiting Rac1. Mol Cancer 2013; 12: 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Qi H, Hou S, Jin X. TIPE2 mRNA overexpression correlates with TNM staging in renal cell carcinoma tissues. Oncol Lett 2013; 6: 571–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XM, Su JR, Yan SP, Cheng ZL, Yang TT, Zhu Q. A novel inflammatory regulator TIPE2 inhibits TLR4-mediated development of colon cancer via caspase-8. Cancer Biomark 2014; 14: 233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Wei X, Liu L, Liu S, Wang Z, Zhang B et al. TIPE2, a novel regulator of immunity, protects against experimental stroke. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 32546–32555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Y, Sun H, Morrissey S, Porturas T, Liu S, Hua X et al. Critical roles of TIPE2 protein in murine experimental colitis. J Immunol 2014; 193: 1064–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Zhao L, Wang Y, Shao J, Cui J, Lou Y et al. TIPE2 protein prevents injury-induced restenosis in mice. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015; 1852: 1574–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Zhu X, Yang Y, Huang L, Xu J. TIPE2 alleviates systemic lupus erythematosus through regulating macrophage polarization. Cell Physiol Biochem 2016; 38: 330–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Zhu T, Liu W, Qu X, Chen Y, Ren P et al. TIPE2 acts as a negative regulator linking NOD2 and inflammatory responses in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Mol Med (Berl) 2015; 93: 1033–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Zhuang G, Chai L, Wang Z, Johnson D, Ma Y et al. TIPE2 controls innate immunity to RNA by targeting the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Rac pathway. J Immunol 2012; 189: 2768–2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, Su J, Zhang L, Ma J. Crocetin activates Foxp3 through TIPE2 in asthma-associated Treg cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 2015; 37: 2425–2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan YY, Yao RQ, Tong S, Dong N, Sheng ZY, Yao YM. Effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha induced protein 8 like-2 on immune function of dendritic cells in mice following acute insults. Oncotarget 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ruan Q, Wang P, Wang T, Qi J, Wei M, Wang S et al. MicroRNA-21 regulates T-cell apoptosis by directly targeting the tumor suppressor gene Tipe2. Cell Death Dis 2014; 5: e1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YH, Yan HQ, Wang F, Wang YY, Jiang YN, Wang YN et al. TIPE2 inhibits TNF-alpha-induced hepatocellular carcinoma cell metastasis via Erk1/2 downregulation and NF-kappaB activation. Int J Oncol 2015; 46: 254–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, Zhao Q, Zhang H, Han B, Liu S, Han M et al. TIPE2, a negative regulator of TLR signaling, regulates p27 through IRF4-induced signaling. Oncol Rep 2016; 35: 2480–2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Tao M, Wu J, Meng Y, Xu C, Tian Y et al. Adenovirus-directed expression of TIPE2 suppresses gastric cancer growth via induction of apoptosis and inhibition of AKT and ERK1/2 signaling. Cancer Gene Ther 2016; 23: 98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Zhang H, Xu C, Xu H, Zhou X, Xie Y et al. TIPE2 functions as a metastasis suppressor via negatively regulating beta-catenin through activating GSK3beta in gastric cancer. Int J Oncol 2016; 48: 199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suo LG, Cui YY, Bai Y, Qin XJ. Anti-inflammatory TIPE2 inhibits angiogenic VEGF in retinal pigment epithelium. Mol Immunol 2016; 73: 46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Fayngerts S, Wang P, Sun H, Johnson DS, Ruan Q et al. TIPE2 protein serves as a negative regulator of phagocytosis and oxidative burst during infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: 15413–15418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Y, Zhang G, Geng M, Zhang W, Cui J, Liu S. TIPE2 negatively regulates inflammation by switching arginine metabolism from nitric oxide synthase to arginase. PLoS One 2014; 9: e96508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Zhang W, Lou Y, Xi W, Cui J, Geng M et al. TIPE2 deficiency accelerates neointima formation by downregulating smooth muscle cell differentiation. Cell Cycle 2013; 12: 501–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Y, Liu S, Zhang C, Zhang G, Li J, Ni M et al. Enhanced atherosclerosis in TIPE2-deficient mice is associated with increased macrophage responses to oxidized low-density lipoprotein. J Immunol 2013; 191: 4849–4857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu MW, Su MX, Zhang W, Wang L, Qian CY. Atorvastatin increases lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of tumour necrosis factor-alpha-induced protein 8-like 2 in RAW264.7 cells. Exp Ther Med 2014; 8: 219–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Hao C, Zhang W, Shao J, Zhang N, Zhang G et al. Identical expression profiling of human and murine TIPE3 protein reveals links to its functions. J Histochem Cytochem 2015; 63: 206–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Wang J, Fan C, Li H, Sun H, Gong S et al. Crystal structure of TIPE2 provides insights into immune homeostasis. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2009; 16: 89–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]